Abstract

Introduction

Acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) leads to rapid deterioration of pulmonary function and quality of life. It is unclear whether the prognosis for AECOPD differs depending on the bacterium or virus identified. The purpose of this study is to determine whether readmission of patients with severe AECOPD varies according to the bacterium or virus identified.

Methods

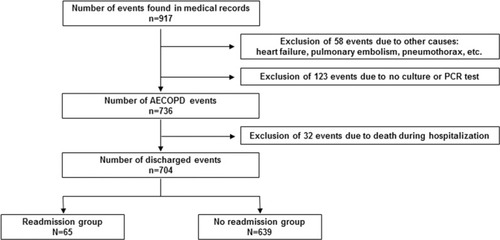

We performed a retrospective review of medical records of 704 severe AECOPD events at Korea University Guro Hospital from January 2011 to May 2017. We divided events into two groups, one in which patients were readmitted within 30 days after discharge and the other in which there was no readmission.

Results

Of the 704 events, 65 were followed by readmission within 30 days. Before propensity score matching, the readmission group showed a higher rate of bacterial identification with no viral identification and a higher rate of identification with the Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P=0.003 and P=0.007, respectively). Using propensity score matching, the readmission group still showed a higher P. aeruginosa identification rate (P=0.030), but there was no significant difference in the rate of bacterial identification, with no viral identification (P=0.210). In multivariate analysis, the readmission group showed a higher P. aeruginosa identification rate than the no-readmission group (odds ratio, 4.749; 95% confidence interval, 1.296–17.041; P=0.019).

Conclusion

P. aeruginosa identification is associated with a higher readmission rate in AECOPD patients.

Introduction

Patients with COPD frequently experience worsening of symptoms, including increased sputum and dyspnea. Acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) is defined as a sudden worsening of COPD symptoms that requires additional treatment.Citation1 Hospitalization is sometimes required depending on AECOPD severity and some patients are hospitalized repeatedly.Citation2 AECOPD impacts quality of life, accelerates the decline in pulmonary function, and increases mortality.Citation3–Citation5 Appropriate treatment is needed to prevent frequent acute exacerbation and hospitalization.

Causes of AECOPD include bacterial and respiratory viral infections and irritants such as air pollutants.Citation6,Citation7 In many cases, the exact cause of AECOPD is unknown. It also remains unclear how causes of AECOPD are related to its prognosis. For example, it is unknown whether the prognosis for severe AECOPD differs depending on the bacterium or virus identified as a cause of infection. Many studies have been conducted on the relationship between the prognosis of COPD and the bacterial or respiratory viral pathogens. And Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been suggested to be associated with a poor prognosis.Citation8,Citation9 The purpose of this study is to analyze AECOPD readmission events and determine whether the prognosis varies with the bacterium or virus identified.

Methods

Data recruitment

We retrospectively found 736 patients diagnosed with severe AECOPD in Korea University Guro Hospital from January 2011 to May 2017 (). Thirty-two AECOPD (4.4%) died during hospitalization. We analyzed 704 patients with AECOPD who were discharged after treatment. Because many other studies of AECOPD had used 30 days as a standard of readmission, we did likewise.Citation10,Citation11 Events were divided into two groups, one in which the patient was readmitted within 30 days after discharge and the other with no readmission within 30 days. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea University Guro Hospital (KUGH16131-002). This study was a retrospective study, so patient consent was not necessary, and we maintained patient confidentiality.

Figure 1 Study design.

AECOPD was defined as “worsening of a patient’s respiratory symptoms beyond normal day-to-day variation.” Severe AECOPD was defined as AECOPD requiring hospitalization.Citation12 Events were included if the following criteria were met: 1) the patient had a previous spirometry that showed airway obstruction (a ratio of forced expiratory volume in the first second to forced vital capacity of <70% in postbronchodilator spirometry);Citation1 2) the patient was diagnosed with severe AECOPD; 3) the patient was discharged after treatment and continuously followed up; and 4) the patient was >40 years old.

Medical records were reviewed and analyzed for the following data: age, gender, smoking history, comorbidities, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage, inhaler use, pulmonary oral medication use, use of home oxygen therapy, and culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay data for identification of the bacterium or virus. A real-time PCR can detect influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, coronavirus, rhinovirus, enterovirus, adenovirus, bocavirus, and metapneumovirus. The three most frequently identified bacteria and viruses were analyzed in the study. All cultures and PCR assays were performed within 24 hours of admission.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20 software (SPSS for windows, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD and categorical variables as number and percentage of each group. Variables were analyzed by comparison between the two groups (readmission and no readmission). Continuous variables were compared using a Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney test. Categorical variables were compared using a chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test; Fisher’s exact test was used when the expected number of events was <5.

To compensate for bias and differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups, we performed propensity score matching. Propensity scores were calculated for each patient using multivariable logistic regression based on the covariates (all variables in and ). Matching was performed using the nearest neighbor method to select for the most similar propensity scores. We performed 1:1 matching and reported a standardized mean difference (d) effect size to express the suitability of matching.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics in readmission and no-readmission groups before and after propensity score matching

Table 2 Pulmonary medication or treatment in readmission and no-readmission groups before and after propensity score matching

After propensity score matching, we performed multivariate analysis using logistic regression. Logistic regression analysis was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. In multivariate analysis, we analyzed factors that showed meaningful values in univariate analysis after propensity score matching. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. We estimated odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 704 severe AECOPD events, 65 led to readmission within 30 days after discharge. After propensity score matching, the number of events in each group was 52. The mean age was >70 years in all groups. The proportion of males was higher than that of females in all groups. The majority of patients were at GOLD stage II or III. All variables related to baseline characteristics showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups. shows detailed baseline characteristics for the two groups before and after propensity score matching.

Pulmonary medication or treatment

We analyzed pulmonary medication use or treatment before admission. Most patients (80%) were using inhalers. Triple therapy was the most commonly used type of inhaler in all groups. Half of the patients were taking mucolytic agents. Oral steroids were used in 5% of patients. Oxygen therapy at home was used by 20% of patients. Before propensity score matching, oral medication use and home oxygen therapy were greater in the readmission group; after propensity score matching, there was no significant difference. shows detailed pulmonary medication or treatment data for the two groups before and after propensity score matching.

Microbiological analysis

We classified AECOPD events as only bacterial pathogen identification, only viral pathogen identification, bacterial–viral coidentification, and no pathogen identification. A bacterial or viral infection was identified in 60% of events. Before propensity score matching, the only bacterial pathogen identification rate was significantly greater in the readmission group (P=0.003); after matching, the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.063). There were no significant differences for the other variables.

We also analyzed the most frequently identified infectious bacteria and viruses in severe AECOPD. The three most commonly identified bacteria were P. aeruginosa, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae; the three most commonly identified viruses were influenza virus, rhinovirus, and parainfluenza virus. Before propensity score matching, the P. aeruginosa identification rate was significantly greater in the readmission group than in the no-readmission group (P=0.007); there were no significant differences in identification rates for the other bacteria or viruses. After matching, the P. aeruginosa identification rate remained significantly greater in the readmission group (P=0.030). shows detailed microbiological data for the two groups before and after propensity score matching.

Table 3 Identified pathogen in readmission events and no-readmission groups before and after propensity score matching

Multivariate analysis

We performed multivariate analysis of P. aeruginosa identification rates. First, we adjusted the propensity score and variables associated with prognosis. The P. aeruginosa identification rate was higher in the readmission groups compared to the no-readmission group (OR, 3.600; 95% CI, 1.077–12.035; P=0.038). Second, we adjusted the propensity score and all variables in and . The P. aeruginosa identification rate was again higher in the readmission groups compared to the no-readmission group (OR, 4.749; 95% CI, 1.296–17.041; P=0.019) ().

Table 4 Multivariate analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa identification rate after propensity score matching

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the effect of bacterial or viral identification on readmission of patients with severe AECOPD. A previous study based in London showed that 10.2% of severe AECOPD patients were readmitted within 30 days after discharge and 17.8% were readmitted within 90 days.Citation13 Other studies of readmission in severe AECOPD have focused on age, comorbidity, inhaler use, and psychological disorders.Citation11,Citation14–Citation16 There is a lack of data on readmission focused on the bacterial or viral identification causing exacerbation. This study is the first to demonstrate that identification of P. aeruginosa correlates with readmission rate in severe AECOPD.

P. aeruginosa is a Gram-negative rod bacterium that can cause opportunistic infections. It is the causative agent of infections mainly in immunocompromised or chronic lung disease patients, including patients with cystic fibrosis or COPD. It has become an important pathogen with increases in immunosuppressive treatments, chemotherapy, and use of intensive care units. P. aeruginosa is currently the most common causative agent of nosocomial infection and the second most common causative agent of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the US.Citation17

P. aeruginosa infections are difficult to treat. First, P. aeruginosa has innate resistance to many of the antimicrobial agents commonly used in the treatment of pneumonia. P. aeruginosa has several broadly specific multidrug efflux systems that provide this innate resistance.Citation18 Second, P. aeruginosa easily acquires resistance compared to other bacteria.Citation19 P. aeruginosa strains possess large genomes (∼5–7 Mbp), can produce multiple secondary metabolites and polymers, and has better quorum sensing than other bacteria, which allows spreading of acquired resistance between bacteria.Citation20 Third, P. aeruginosa secretes virulence factors and impairs the immune system. For example, P. aeruginosa secretes elastase B and escapes phagocytosis.Citation21 P. aeruginosa also secretes exoenzyme S (ExoS), a bifunctional toxin encoded by the exoS gene, which disrupts the pulmonary vascular barrier, resulting in bacteremia.Citation22 The identification of P. aeruginosa means that treatment and complete eradication are difficult. Compared to other bacteria, antibiotics are used for longer times, and the duration of hospitalization is greater, often leading to secondary hospital infections and antibiotic side effects.

In our study, P. aeruginosa is the most commonly identified pathogen. However, in a previous study, the most commonly identified bacteria in AECOPD are S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.Citation23 There are some reasons for this discrepancy. First, the COPD grade in our study is high. P. aeruginosa is most commonly identified in patients at GOLD stages III and IV.Citation24 Meta-analysis has shown that P. aeruginosa identification is statistically higher in COPD patients with bronchiectasis.Citation25 The identification of P. aeruginosa means that the host belongs to the high-risk group. Second, it is a regional characteristic. Unlike the Western study, some studies in Korea and Asia show that P. aeruginosa is most commonly identified.Citation26,Citation27

There are two clinical features when P. aeruginosa is identified in AECOPD patients.Citation28 The most common feature is carriage of P. aeruginosa for a short time followed by clearance (<1 month). The other feature is persistent colonization with P. aeruginosa. There is a debate regarding the prognosis and mortality of stable COPD patients who are colonized by P. aeruginosa.Citation29 There is no clear evidence that antibiotics should be used in this condition. A prospective study showed that P. aeruginosa identification in patients with severe AECOPD was associated with a higher 3-year mortality rate.Citation30 Chronic P. aeruginosa infection has also been shown to increase the mutation rate and antibiotic resistance of proteases and reduce their production.Citation31 Although there is controversy regarding P. aeruginosa infections in patients with stable COPD, the identification of P. aeruginosa in cases of AECOPD means a poor prognosis.

Our study has some limitations. First, this is a retrospective study, so there were limitations in obtaining data. For example, some patients lacked chest computed tomography data, thus limiting analysis of associations with bronchiectasis. And sputum culture assay was not conducted before and after admission. Second, colonization and contamination could not be distinguished in our study. Although sputum results of grade four or five were used to analyze culture results and collection of all specimens was done by trained physicians, additional data to analyze colonization and contamination were lacking. Third, the sample size was small after propensity score matching. So some of the comparisons in this analysis suggest that there may be insufficient statistical power. For example, only the bacterial pathogen identification rate is 38.5% in the readmission group and 26.9% in the no-readmission group. But this difference is not statistically significant. Although this study was a retrospective and single-center study, we analyzed various factors in a large-scale group. An additional large-scale, multicenter, randomized control study is required to confirm our results.

Conclusion

P. aeruginosa infections in severe AECOPD are difficult to treat, and secondary problems often arise. P. aeruginosa infections occur mainly in high-risk patients. In severe AECOPD, P. aeruginosa infections mean poor prognosis and an increased rate of readmission.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting, and revising this paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from Korea University, Seoul, Korea (K1719301).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VogelmeierCFCrinerGJMartinezFJGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report: GOLD Executive SummaryRespirology201722357560128150362

- BurchetteJECampbellGDGeraciSAPreventing Hospitalizations From Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseAm J Med Sci20173531314028104101

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTABhowmikAWedzichaJARelationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2002571084785212324669

- Soler-CataluñaJJMartínez-GarcíaMARomán SánchezPSalcedoENavarroMOchandoRSevere acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2005601192593116055622

- SpencerSCalverleyPMBurgePSJonesPWImpact of preventing exacerbations on deterioration of health status in COPDEur Respir J200423569870215176682

- OgawaKKishiKEtiological and exacerbation factors for COPD. Air pollutionNihon Rinsho201674574374627254939

- MackayAJHurstJRCOPD exacerbations: causes, prevention, and treatmentImmunol Allergy Clin North Am20133319511523337067

- Garcia-VidalCAlmagroPRomaníVPseudomonas aeruginosa in patients hospitalised for COPD exacerbation: a prospective studyEur Respir J20093451072107819386694

- FerrerMIoanasMArancibiaFMarcoMAde la BellacasaJPTorresAMicrobial airway colonization is associated with noninvasive ventilation failure in exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCrit Care Med20053392003200916148472

- GotoTFaridiMKCamargoCAJrHasegawaKTime-varying Readmission Diagnoses During 30 Days After Hospitalization for COPD ExacerbationMed Care201856867367829912841

- BishwakarmaRZhangWKuoYFSharmaGLong-acting bronchodilators with or without inhaled corticosteroids and 30-day readmission in patients hospitalized for COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20171247748628203071

- PauwelsRCalverleyPBuistASCOPD exacerbations: the importance of a standard definitionRespir Med20049829910714971871

- HarriesTHThorntonHCrichtonSSchofieldPGilkesAWhitePTHospital readmissions for COPD: a retrospective longitudinal studyNPJ Prim Care Respir Med20172713128450741

- EchevarriaCSteerJHeslop-MarshallKThe PEARL score predicts 90-day readmission or death after hospitalisation for acute exacerbation of COPDThorax201772868669328235886

- SinghGZhangWKuoYFSharmaGAssociation of Psychological Disorders With 30-Day Readmission Rates in Patients With COPDChest2016149490591526204260

- JeongSHLeeHCarriereKCComorbidity as a contributor to frequent severe acute exacerbation in COPD patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016111857186527536097

- GellatlySLHancockREPseudomonas aeruginosa: new insights into pathogenesis and host defensesPathog Dis201367315917323620179

- PooleKMultidrug efflux pumps and antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related organismsJ Mol Microbiol Biotechnol20013225526411321581

- MoradaliMFGhodsSRehmBHPseudomonas aeruginosa Lifestyle: A Paradigm for Adaptation, Survival, and PersistenceFront Cell Infect Microbiol201773928261568

- GonzálezJEKeshavanNDMessing with bacterial quorum sensingMicrobiol Mol Biol Rev200670485987517158701

- KuangZHaoYWallingBEJeffriesJLOhmanDELauGWPseudomonas aeruginosa elastase provides an escape from phagocytosis by degrading the pulmonary surfactant protein-APLoS One2011611e2709122069491

- BerubeBJRangelSMHauserARPseudomonas aeruginosa: breaking down barriersCurr Genet201662110911326407972

- SethiSEvansNGrantBJMurphyTFNew strains of bacteria and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2002347746547112181400

- MiravitllesMEspinosaCFernández-LasoEMartosJAMaldonadoJAGallegoMRelationship between bacterial flora in sputum and functional impairment in patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Study Group of Bacterial Infection in COPDChest19991161404610424501

- NiYShiGYuYHaoJChenTSongHClinical characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with comorbid bronchiectasis: a systemic review and meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101465147526251586

- ParkHShinJWParkSGKimWMicrobial communities in the upper respiratory tract of patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePLoS One2014910e10971025329665

- DaiMYQiaoJPXuYHFeiGHRespiratory infectious phenotypes in acute exacerbation of COPD: an aid to length of stay and COPD Assessment TestInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015102257226326527871

- MurphyTFThe many faces of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseClin Infect Dis200847121534153619025364

- BoutouAKRasteYReidJAlshafiKPolkeyMIHopkinsonNSDoes a single Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolation predict COPD mortality?Eur Respir J201444379479725034565

- AlmagroPSalvadóMGarcia-VidalCPseudomonas aeruginosa and mortality after hospital admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration2012841364321996555

- Martínez-SolanoLMaciaMDFajardoAOliverAMartinezJLChronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseClin Infect Dis200847121526153318990062