Abstract

Purpose

Improvement in the diagnosis of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap (ACO), and identification of biomarkers for phenotype recognition will encourage good patient care by providing optimal therapy. We investigated club cell secretory protein (CC-16), a protective and anti-inflammatory mediator, as a new candidate biomarker for diagnosing ACO.

Patients and methods

We performed a multicenter cohort study. A total of 107 patients were divided into three groups – asthma, COPD, and ACO – according to the Spanish guidelines algorithm, and enrolled into the study. Serum CC-16 levels were measured using commercial ELISA kits.

Results

Serum CC-16 levels were the lowest in patients with ACO. Low serum CC-16 levels were a significant marker for the ACO even after adjustment for age, sex, and smoking intensity. Serum CC-16 levels were positively correlated with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory flow at 25%–75% of FVC, FEV1/FVC, vital capacity, and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, and were negatively correlated with smoking amount (pack-years), bronchodilator response, fractional residual capacity, residual volume, and number of exacerbations per year. FEV1 and serum CC-16 levels were significantly lower in patients with frequent exacerbations.

Conclusion

Serum CC-16 has the potential to be a biomarker for ACO diagnosis and also treat frequent exacerbations in patients with chronic inflammatory airway diseases.

Introduction

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are very significant public health concerns that are responsible for a substantial disease burden worldwide. Asthma and COPD are generally defined as different diseases, but many previous studies have reported that the two may coexist. It is a known fact that one of these conditions may evolve into the other, creating a condition commonly described as an asthma–COPD overlap (ACO).Citation1–Citation3 However, there is no universally accepted definition and there are many controversial aspects of ACO that lead to diverse epidemiology and outcomes.Citation2 The term “ACO” may be refined when new phenotypes and underlying endotypes are identified,Citation1–Citation3 but it is a suitable interim solution until the biomarkers for asthma–COPD endotypes are recognized.Citation1,Citation4 A better understanding of ACO will encourage good patient care and ensure the provision of optimal therapy.Citation3,Citation5 Moreover, to optimize the diagnostic approaches to chronic airway diseases, further improvements of biomarkers for phenotype and endotype recognition are needed.Citation6

Club cell secretory protein (CC-16) is one of the many proteins that belong to the family of CC proteins. Club cells have a protective role in the respiratory system: they repair the airway after injury and detoxify harmful substances by secreting anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory proteins.Citation7,Citation8 CC-16 serves as an important protective and anti-inflammatory mediator in the lung, and patients deficient in CC-16 are known to progress to COPD.Citation9,Citation10 Serum concentrations of CC-16 are decreased in patients with chronic lung damage as a consequence of the destruction of club cells.Citation8,Citation9,Citation11 The serum level of CC-16 is reported to be low in patients with asthma or COPD, and in smokers.Citation12–Citation14 However, the role of CC-16 in ACO has not been fully evaluated. Thus, we investigated serum CC-16 as a new candidate biomarker for the diagnosis of ACO using commercial ELISA kits.

Materials and methods

Study design

This cohort study was designed to find useful biomarkers in chronic airway disease. Patients were enrolled from the registry of chronic airway disease during the period from June 2015 to May 2016. This was a multicenter study and three hospitals were included: Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul St Mary’s Hospital, and Chonbuk National University Hospital. We included patients aged over 19 years and patients diagnosed with asthma, COPD, or ACO. Inclusion criteria were restricted to patients who had been in a stable state without exacerbation for at least three months prior to study inclusion. We excluded patients with bronchiectasis, sequela from prior tuberculosis infection, interstitial lung disease, and all other diseases that could lead to airflow limitation.

Patients were divided into COPD, asthma, and ACO groups according to patients’ age, smoking history and amount, past medical history, pulmonary function test (PFT) results, and their blood eosinophil counts. The group COPD (n=38) was defined according to the American Thoracic Society and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines.Citation15 The group asthma (n=32) was selected on the basis of the Global Initiative for Asthma Guidelines.Citation16 The group ACO (n=37) was defined according to algorithms of Spanish COPD guidelines and the Spanish Guidelines for the Management of Asthma.Citation17 Inclusion criteria for ACO group were as follows: age >35 years, smoking history (≥10 pack-years) or exposure to other inhalation agents, airflow obstruction (confirmed by post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC] <70%) with persistent respiratory symptoms, known asthma or a very positive bronchodilator response (BDR ≥400 mL and FEV1 ≥15%), and/or blood eosinophilia (≥300 cells·mm−3). For subgroup analysis of ACO, we sub-categorized ACO in patients with “smoking-related obstructive asthma” and “COPD with a very positive BDR and/or blood eosinophilia”. We categorized patients aged >35 years with smoking history (≥10 pack-years) or exposure to other inhalation agents, airflow obstruction with persistent respiratory symptoms, and known asthma as patients with “smoking-related obstructive asthma”. We defined patients aged >35 years with smoking history (≥10 pack-years) or exposure to other inhalation agents, airflow obstruction with persistent respiratory symptoms, and a very positive BDR and/or blood eosinophilia as patients with “COPD with a very positive BDR and/or blood eosinophilia”.

At baseline, information on the following parameters was collected: age, sex, body mass index, past medical history, and smoking history and amount. Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea score, St George Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score, COPD assessment test score, and/or asthma control test score were also evaluated for symptom scores. For PFT results, we performed spirometry, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and total lung volume. Blood tests including eosinophil count were routinely performed in the overnight, fasted, and medication-free state, on the day of enrolment. Peripheral whole-venous blood at baseline was collected into EDTA tubes, and serum was prepared by centrifugation for 10–15 minutes at 4,500 rpm and stored at −80°C until analyzed. CC-16 was measured using ELISA kits (BioVendor GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany).

Exacerbation history at one year from enrolment was determined. We defined an exacerbation as a sustained deterioration of acute respiratory symptoms, which required a change in regular medication with an unscheduled hospital visit, beyond stable day-to-day variations. When patients experienced moderate (need treatment with antibiotics and/or corticosteroids) exacerbations more than twice or one or more severe (need hospitalization) exacerbations within one year, we called them “frequent exacerbators”.

The institutional review boards of three hospitals approved this study protocol (Korea University Guro Hospital: KUGH 13246; Seoul St Mary’s Hospital: KC15OIMI0553; and Chonbuk National University Hospital: 2015-01-018-005). This study fulfilled the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written informed consent.

Statistical analyses

We presented data as median and IQR for continuous parameters and compared variables by the Kruskal−Wallis test; we further analyzed each of the two groups using the Mann−Whitney U-test with Bonferroni correction (defined α<0.017 as significant). For categorical parameters, we presented data as percentages and numbers and compared variables using Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. For presenting correlations between variables, Spearman’s correlation analysis was used. We defined P<0.05 as significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Ver 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 107 patients are provided in . Patients with COPD were older than those with asthma. All patients with COPD and ACO had a smoking history by definition, and 9.4% of the patients with asthma were smokers. Percentage of comorbid allergic rhinitis was significantly lower in patients with COPD, compared to those with asthma or ACO. Patients with COPD presented higher mMRC and SGRQ scores than did patients with asthma. Regarding PFTs, BDR in patients with ACO was higher than that in patients with asthma or COPD. Median creatinine clearance rates were similar (100.5 [71.5–120.9] mL/min in asthma group, 95.7 [66.4–123.0] mL/min in COPD group, and 95.7 [66.4–122.9] mL/min in ACO group; P=0.61).

Table 1 Comparison of the baseline characteristics of patients with different chronic inflammatory airway diseases

Serum CC-16 levels in chronic airway disease

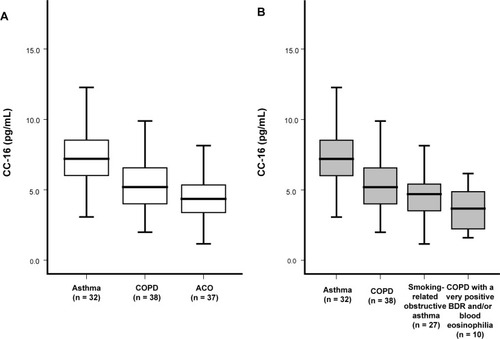

When we compared serum CC-16 levels among asthma, COPD, and ACO groups, CC-16 levels were the lowest in the ACO group (). The levels of CC-16 did not differ significantly between patients with smoking-related obstructive asthma (n=27) and COPD, with a very positive BDR and/or blood eosinophilia (n=10; ).

Figure 1 Serum CC-16 levels in chronic inflammatory airway diseases according to disease classification.

Abbreviations: ACO, asthma–COPD overlap; BDR, bronchodilator response; CC, club cell secretory protein; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Multivariate logistic regression showed that decreased CC-16 levels were a significant parameter of ACO even after adjustment for age, sex, and smoking amount (OR: 0.664; 95% CI: 0.525–0.829; P=0.001).

CC-16 levels and parameters

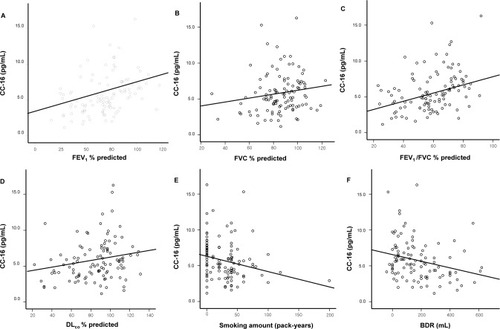

In the total study population, CC-16 levels were positively correlated with FEV1 (R=0.423; P<0.001), FVC (R=0.192; P=0.047), forced expiratory flow at 25%–75% of FVC (FEF25%–75%) (R=0.394; P<0.001), FEV1/FVC (R=0.397; P<0.001), vital capacity (R=0.191; P=0.049), and DLCO (R=0.255; P=0.008), and were negatively correlated with smoking amount (pack-years) (R=−0.258; P=0.007), BDR (R=−0.313; P=0.001), fractional residual capacity (R=−0.204; P=0.035), residual volume (R=−0.301; P=0.002), and number of exacerbations per year (R=−0.229; P=0.018; ).

Figure 2 Correlation between serum CC-16 levels and parameters.

Abbreviations: BDR, bronchodilator response; CC, club cell secretory protein; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

CC-16 levels in frequent exacerbators

To evaluate the role of serum CC-16 in exacerbation, we compared the characteristics of patients with frequent exacerbations and those without frequent exacerbations (). FEV1 and CC-16 were significantly lower in frequent exacerbators.

Table 2 Comparison of frequent and nonfrequent exacerbators

Discussion

This study demonstrated that serum CC-16 levels were significantly lower in patients with ACO than the levels in patients with asthma or COPD. Moreover, CC-16 levels were also lower in patients with frequent exacerbations than the levels in those without frequent exacerbation. Serum CC-16 levels were decreased in patients with a severe smoking habit, severe airflow obstruction, high BDR, and frequent exacerbations. Serum CC-16 is a protective and anti-inflammatory marker, and decreased CC-16 might lead to severe inflammation and poor control of diseases. Thus, the current results support low serum CC-16 levels as an indicator of severe obstruction with airway reversibility and frequent exacerbations, in chronic airway inflammatory diseases.

CC-16 is a homodimeric pneumoprotein and it is mostly generated by nonciliated bronchial epithelial cells.Citation14,Citation18 In vitro, ex vivo, and animal studies indicate that CC-16 plays a role in reducing inflammation of the airways and protecting the respiratory tract from oxidative stress.Citation14,Citation18 Decreased serum levels of CC-16 have been found in smokers compared to nonsmokers, which might be attributable to smoking-induced club cell toxicity.Citation19 In COPD, CC-16 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and serum has been reported to be lower compared to controls.Citation19,Citation20 CC-16 deficiency increases smoking-induced pulmonary inflammation.Citation21 Integrative genomics has shown CC-16 to be related to lung function decline in individuals with COPD. This supports CC-16 as a promising biomarker for its potential role in the pathogenesis of COPD.Citation22 Moreover, reduced CC-16 levels are associated with an accelerated decline in lung function over time, as well as COPD severity and progression.Citation19,Citation23 Similar to previous studies, CC-16 was lower in patients with low FEV1, DLCO, FVC, and FEV1/FVC, which reflects the severity of obstruction and emphysema. This can be explained by the increased destruction of club cells in patients having chronic inflammatory airway diseases with severely impaired lung function.

Interestingly, we also found that CC-16 was significantly lower in frequent exacerbators, and that CC-16 was negatively correlated with the frequency of acute exacerbations. Labonté et al described that increased CC-16 could predict lower risk of subsequent exacerbations during follow-up, while decreased CC-16 could reflect increased exacerbation frequency.Citation24 CC-16 was negatively correlated with the two-year acute exacerbation frequency, and positively correlated with FEV1 and FEV1/FVC in one study.Citation25 In line with previous studies, we confirmed that serum CC-16 could be a prognostic factor for exacerbations in chronic inflammatory airway disease.

Lower CC-16 serum levels have been associated not only with impaired lung function, but also with a higher degree of airway responsiveness.Citation26 In previous asthma studies, CC-16 was significantly lower in patients with asthma than in healthy controls.Citation27 Patients with long-lasting asthma, a condition that is commonly observed in ACO, have lower levels of serum CC-16 than do those with a history of asthma of less than 10 years.Citation28 A correlation between lung function (FEV1/FVC) and serum CC-16 levels has been observed in patients with asthma,Citation29 which was confirmed in our study. Moreover, previous studies have shown that airway hyperresponsiveness is inversely correlated with serum CC-16 levels,Citation23 and CC-16 is relevant to small-airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with asthma.Citation30 Likewise, our study revealed that CC-16 was negatively correlated with BDR. The negative correlation of CC-16 with BDR, the smoking amount, and the tendency toward acute exacerbations could explain the significantly decreased serum CC-16 levels observed in ACO. However, decreased CC-16 levels in ACO were not independently affected by the smoking amount, which is a well-known factor contributing to low CC-16. Moreover, even though there were significant differences in terms of sex between three groups, a previous study showed that sex had no effect on serum CC-16 levels.Citation14 Even after adjusting age, sex, and smoking amount, the decrease in CC-16 levels was a significant parameter of ACO, which indicates CC-16 as a possible candidate biomarker for ACO.

Our study has some limitations. First, BALF concentrations of CC-16 were not evaluated. However, CC-16 could be found both in the airways and circulation. Even though BALF concentrations of CC-16 reflect cellular damage and are greater than those in serum,Citation11,Citation18 normal serum levels are sufficiently high to be measured using techniques such as the ELISA. Repeated measurements of CC-16 in a subpopulation from a large cohort revealed that serum CC-16 is a stable marker over time.Citation31 Therefore, serum CC-16 could potentially provide a less-invasive method for assessing airway damage.Citation11,Citation20 Second, a comparison with normal controls was not done. Although we could not compare the serum CC-16 levels of normal controls, serum CC-16 levels were significantly lower in patients with COPD than in patients with asthma, most of whom were nonsmokers. Moreover, it is well-known that control levels of serum CC-16 are higher than those in patients with COPD or asthma. Thus, it could be inferred that the serum CC-16 levels of ACO might be lower than those of healthy controls. Third, this was not a randomized study but a cohort study; thus, parameters were not repeated. There might have been a selection bias. As this was a pilot study, our findings should be validated by another independent cohort study to confirm CC-16 as a biomarker. Moreover, future studies are warranted to determine the cutoffs and diagnostic accuracy of the biomarker that may be optimal for correctly classifying the three disease groups. Despite these limitations, the strength of our study was that we identified serum CC-16 as a prognostic predictor of chronic inflammatory diseases and as a possible biomarker for ACO.

Conclusion

Serum CC-16 levels were significantly lower in patients with ACO and in those with severe obstruction with high reversibility and frequent exacerbations. Decreased serum CC-16 could possibly distinguish patients with ACO or frequent exacerbators in chronic inflammatory airway diseases.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting, and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

We thank SY Hwang who supported for the statistical analyses.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BarrechegurenMEsquinasCMiravitllesMThe asthma–COPD overlap syndrome: a new entity?COPD Res Pract2015118

- CazzolaMRoglianiPDo we really need asthma–chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome?J Allergy Clin Immunol2016138497798327372569

- PostmaDSRabeKFThe asthma-cOPD overlap syndromeN Engl J Med2015373131241124926398072

- WatanabeHThe asthma–COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) What is the significance COPD associated with asthma?NakamuraHAoshibaKChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Respiratory Disease Series: Diagnostic Tools and Disease ManagementsSingaporeSpringer2017299311

- BarnesPJTherapeutic approaches to asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndromesJ Allergy Clin Immunol2015136353154526343937

- McdonaldVMHigginsIWoodLGGibsonPGMultidimensional assessment and tailored interventions for COPD: respiratory utopia or common sense?Thorax201368769169423503624

- GamezASGrasDPetitASupplementing defect in club cell secretory protein attenuates airway inflammation in COPDChest201514761467147625474370

- Laucho-ContrerasMEPolverinoFGuptaKProtective role for club cell secretory protein-16 (CC16) in the development of COPDEur Respir J20154561544155625700379

- ZhuLdiPYWuRPinkertonKEChenYRepression of CC16 by cigarette smoke (CS) exposurePLoS One2015101e011615925635997

- ParkHYChurgAWrightJLClub cell protein 16 and disease progression in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013188121413141924245748

- BroeckaertFClippeAKnoopsBHermansCBernardAClara cell secretory protein (CC16): features as a peripheral lung biomarkerAnn N Y Acad Sci2000923687711193780

- KnabeLFortAChanezPBourdinAClub cells and CC16: another “smoking gun”? (With potential bullets against COPD)Eur Respir J20154561519152026028613

- SonarSSEhmkeMMarshLMClara cells drive eosinophil accumulation in allergic asthmaEur Respir J201239242943821828027

- LakindJSHolgateSTOwnbyDRA critical review of the use of Clara cell secretory protein (CC16) as a biomarker of acute or chronic pulmonary effectsBiomarkers200712544546717701745

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD2017 Available from: www.goldcopd.orgAccessed August 1, 2017

- GINA/GOLD Joint Report2015 Asthma, COPD and Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS) [Internet]BethesdaGlobal Initiative for Asthma2016 [cited 2017 April] Available from: http://ginasthma.org/asthma-copd-and-asthma-copdoverlap-syndrome-acos/AccessedAugust 1, 2017

- MiravitllesMAlvarez-GutierrezFJCalleMAlgorithm for identification of asthma-COPD overlap: consensus between the Spanish COPD and asthma guidelinesEur Respir J2017495170006828461301

- BroeckaertFBernardAClara cell secretory protein (CC16): characteristics and perspectives as lung peripheral biomarkerClin Exp Allergy200030446947510718843

- ShijuboNItohYYamaguchiTSerum and BAL Clara cell 10 kDa protein (CC10) levels and CC10-positive bronchiolar cells are decreased in smokersEur Respir J1997105110811149163654

- BernardAMarchandiseFXDepelchinSLauwerysRSibilleYClara cell protein in serum and bronchoalveolar lavageEur Respir J1992510123112381486970

- Laucho-ContrerasMEPolverinoFGuptaKProtective role for club cell secretory protein-16 (CC16) in the development of COPDEur Respir J20154561544155625700379

- ObeidatMZhouGLiXClub cell secretory protein 16 (cc16) is causally related to lung function decline in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease using integrative genomicsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017195A2439

- ParkHYChurgAWrightJLClub cell protein 16 and disease progression in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013188121413141924245748

- LabontéLEBourbeauJDaskalopoulouSSClub cell-16 and relB as novel determinants of arterial stiffness in exacerbating COPD patientsPLoS One2016112e014997426914709

- ZhangJDaiRZhaiWFengNLinJThe efficacy of modified neutrophil alkaline phosphatase score, serum IL-6, IL-18 and CC16 levels on the prognosis of moderate and severe COPD patientsBiomed Res2017281776517655

- RavaMLe MoualNDumontXSerum club cell protein 16 is associated with asymptomatic airway responsiveness in adults: findings from the French epidemiological study on the genetics and environment of asthmaRespirology20152081198120526439880

- GioldassiXMPapadimitriouHMikrakiVKaramanosNKClara cell secretory protein: determination of serum levels by an enzyme immunoassay and its importance as an indicator of bronchial asthma in childrenJ Pharm Biomed Anal200434482382615019060

- ShijuboNItohYYamaguchiTSerum levels of Clara cell 10-kDa protein are decreased in patients with asthmaLung1999177145529835633

- YeQFujitaMOuchiHSerum CC-10 in inflammatory lung diseasesRespiration200471550551015467329

- BommartSMarinGMolinariNClub cell secretory protein serum concentration is a surrogate marker of small-airway involvement in asthmatic patientsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2017140258158428108336

- DickensJAMillerBEEdwardsLDSilvermanEKLomasDATal-SingerREvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study investigators. COPD association and repeatability of blood biomarkers in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Res20111214622054035