Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to examine the changing influence over time of comorbid heart disease on symptoms and health status in patients with COPD.

Patients and methods

This is a prospective cohort study of 495 COPD patients with a baseline in 2005 and follow-up in 2012. The study population was divided into three groups: patients without heart disease (no-HD), those diagnosed with heart disease during the study period (new-HD) and those with heart disease at baseline (HD). Symptoms were measured using the mMRC. Health status was measured using the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) and the COPD Assessment Test (CAT; only available in 2012). Logistic regression with mMRC ≥2 and linear regression with CCQ and CAT scores in 2012 as dependent variables were performed unadjusted, adjusted for potential confounders, and additionally adjusted for baseline mMRC, respectively, CCQ scores.

Results

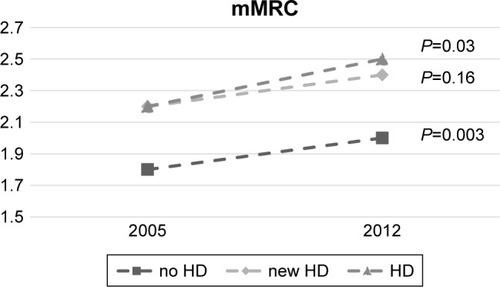

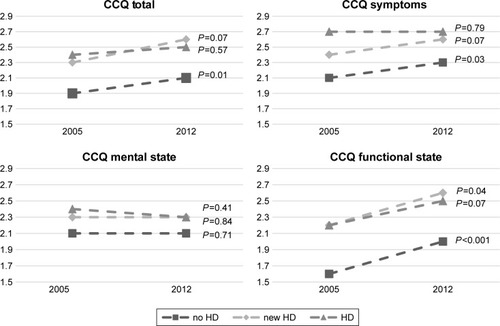

Mean mMRC worsened from 2005 to 2012 as follows: for the no-HD group from 1.8 (±1.3) to 2.0 (±1.4), (P=0.003), for new-HD from 2.2 (±1.3) to 2.4 (±1.4), (P=0.16), and for HD from 2.2 (±1.3) to 2.5 (±1.4), (P=0.03). In logistic regression adjusted for potential confounding factors, HD (OR 1.71; 95% CI: 1.03–2.86) was associated with mMRC ≥2. Health status worsened from mean CCQ as follows: for no-HD from 1.9 (±1.2) to 2.1 (±1.3) with (P=0.01), for new-HD from 2.3 (±1.5) to 2.6 (±1.6) with (P=0.07), and for HD from 2.4 (±1.1) to 2.5 (±1.2) with (P=0.57). In linear regression adjusted for potential confounders, HD (regression coefficient 0.12; 95% CI: 0.04–5.91) and new-HD (0.15; 0.89–5.92) were associated with higher CAT scores. In CCQ functional state domain, new-HD (0.14; 0.18–1.16) and HD (0.12; 0.04–0.92) were associated with higher scores. After additional correction for baseline mMRC and CCQ, no statistically significant associations were found.

Conclusion

Heart disease contributes to lower health status and higher symptom burden in COPD but does not accelerate the worsening over time.

Introduction

COPD is a common disease causing significant morbidity and mortality worldwide.Citation1 Symptom burden and health status are important patient-related outcomes in the management of patients with COPD. A multidimensional assessment of disease severity, including FEV1, health status and exacerbation frequency, is advocated by the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).Citation2 For the measurement of dyspnea symptom burden, the use of mMRC is widespread.Citation3 For the assessment of health status, GOLD recommends the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) that was developed in 2009.Citation4 The Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) is considered by GOLD as an instrument with equal qualities.Citation5 Since it has been in use since 2003, it is more suitable for longitudinal analysis.

COPD is associated with a high prevalence of comorbid conditions, and COPD patients have a two to five times higher risk of developing heart disease.Citation6 The prevalence of ischemic heart disease is estimated to be 22%–33% and chronic heart failure 14%–24% in patients with COPD.Citation7–Citation9 The observed association between COPD and heart disease can be explained partly by shared risk factors such as smoking, age, and inactivity. However, it is also thought that a systemic inflammatory process related to COPD may independently increase the risk of heart disease.Citation10

Comorbid heart disease has, in cross-sectional studies, been shown to be associated with lower health status in patients with COPD.Citation11–Citation13 It has also been reported that disease-specific health status worsens over time in patients with COPD,Citation14–Citation16 although this could not be shown with a general instrument in a group of patients with low disease severity.Citation17 The aim of this study was to examine the changing influence over a 7-year follow-up period of comorbid heart disease on symptoms of dyspnea measured by mMRC and health status measured by CCQ and CAT in patients with COPD.

Patients and methods

Data collection

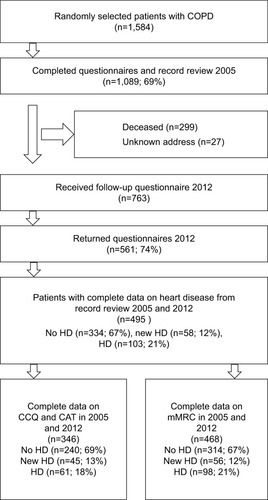

The data were obtained from the PRAXIS study cohort that was created in 2005 with a follow-up in 2012.Citation14 The PRAXIS study is based on the data from 14 hospitals and 56 primary health care centers in seven counties in mid-Sweden. A total of 1,548 patients were randomly selected from lists with patients aged 34–75 years with an ICD 10 diagnosis code J44 for COPD recorded in their medical records during 2000–2003. The random selection was made from the respective health care unit’s diagnosis list by a research nurse, using an Internet-based program (https://www.random.org/). A patient questionnaire was sent to these patients. In 2012, all patients who were still alive received a similar questionnaire as in 2005. A total of 561 patients returned both the baseline and the follow-up questionnaires ().

Figure 1 Flow chart patient selection.

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD Assessment Test; CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire; HD, heart disease.

Patient characteristics and measures

The medical records were reviewed at baseline for the period 2000–2003 and again at follow-up for the period 2004–2012. The record review produced information on a doctor’s diagnosis of heart disease, hypertension, depression, diabetes and data on lung function. Heart disease was defined as a doctor’s diagnosis of ischemic heart disease or heart failure registered in the medical records. The study population was divided into three groups: COPD patients without a diagnosis of heart disease (no HD), those who were diagnosed with heart disease during the study period 2003–2012 (new HD) and those who had a heart disease diagnosis at the start of the study 2003 (HD). In patients where spirometry data were available at baseline (n=216), their disease was graded based on the FEV1 expressed as a percentage of the European Community for Steel and Coal reference values (FEV1%pred).Citation18

The questionnaires provided information on age, sex, smoking status, level of education, exacerbations in the previous 6 months, height, weight, mMRC and CCQ. In addition, the questionnaire in 2012 included CAT.

For patient characteristics, baseline data from 2005 were used. Age was categorized into three groups: ≤60 years, 61–70 years, and >70 years. Smoking status was categorized into “current daily smoking” and “not current daily smoking”. The latter group included patients who never smoked, had stopped smoking or smoked occasionally. The dichotomous educational variable identified the most highly educated group as those who had continued full-time education for at least 2 years beyond the Swedish compulsory school period of 9 years. An exacerbation was defined as an emergency visit or the need for a course of oral steroids during the previous 6 months due to worsening of COPD symptoms. Height and weight were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2. Underweight was defined as a BMI <20, normal weight as a BMI ≥20 and <25, overweight as BMI ≥25 and <30 and obesity as BMI ≥30.

Dyspnea

Dyspnea was measured by the mMRC, where a score of 0 or 1 corresponds to no dyspnea or dyspnea on strenuous exercise, and scores of 2 and more denote increasing limitation of activity due to dyspnea in daily life. The scale has been validated and is frequently used in clinical and research settings.Citation3 For regression analysis, the mMRC score was dichotomized to low burden of dyspnea (mMRC score of 0 and 1) and patients high burden of dyspnea (score of 2–4) according to GOLD.Citation2

Health status

The CCQ includes ten items about the patients’ health the previous week, distributed over three domains: symptoms, mental state and functional state.Citation19 The symptoms domain contains questions on dyspnea, cough and phlegm; the mental state describes the feelings of depression and concerns about breathing or getting worse; and the functional state assesses the limitations in different activities of daily life due to lung disease. Answers are given on 7-point scale from 0 to 6. The main outcome is the total mean CCQ value; a separate mean score for each domain can also be calculated. A higher score indicates lower health status. The minimal clinically important difference for CCQ is established to be 0.4 units.Citation20 The CAT includes eight items about the patients’ experience of cough, mucus production, chest tightness, dyspnea on exercise, limitation of activities at home, sense of confidence about leaving the house, sleep and energy level.Citation4 The patient scores the symptoms on a 6-point scale from 0 to 5. A high score indicates lower health status. The main outcome measure is the sum of the scores, varying between 0 and 40. The minimal clinically important difference for CAT has been suggested to be 2–3 units.Citation20 The health status instruments, CCQ and CAT, correlate well with St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and with each other and can be used as equivalents for measuring health status.Citation4,Citation5,Citation21

Statistical analyses

Categorical data were expressed using frequencies and percentages, while continuous data were expressed using mean values and SDs. The chi-squared test and Student’s t-test were used to examine the differences in characteristics between patients without heart disease (no HD) and patients with heart disease at baseline (HD) and those who were diagnosed with heart disease during the study period (new HD). Logistic regression analysis used the dichotomous mMRC score ≥2 as the dependent variable. Heart disease in 2012 (three groups – no HD, new HD and HD), and the potential confounding factors of age, sex, level of education, smoking status, presence of exacerbations in the previous 6 months, diabetes, hypertension, depression, and BMI at baseline were used as independent variables. Heart disease, age and BMI were modeled as a series of binary dummy variables. Linear regression analysis used mean CCQ score and total CAT score in 2012 as dependent variables. The same independent variables as in the analysis of mMRC were investigated. All the analyses were performed as unadjusted, adjusted and additionally adjusted for the value of the outcome measure at baseline. In adjusted analysis, only the variables with a statistically significant association (P<0.05) in unadjusted analysis were included. As CAT was not available in 2005, the mean CCQ score at baseline was used as replacement for CAT at baseline. Stratification and multiplicative interaction analyses were used to investigate potential effect modification by sex and different age groups (≤60, 61–70 and >70 years). The main analyses for mMRC, CCQ and CAT were all repeated in the subgroup with available spirometry data, with additional adjustment for the FEV1%pred groups GOLD I-IV.Citation2 A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant. SPSS version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used.

Ethics

The study was approved by the regional ethical review board of Uppsala University (Dnr 2004:M-445 and Dnr 2010/090). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

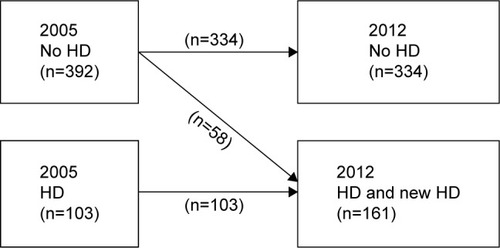

Patient characteristics at baseline are shown in . COPD patients with comorbid heart disease during the whole study were more often male, older, lower educated and selected from the hospital care population, than those without heart disease. The group with incident heart disease was older and had relatively less daily smokers compared to those without heart disease. The number of COPD patients with comorbid heart disease for each patient sample and the total group is presented in .

Table 1 Patient characteristics in 2005 by HD group in 2012

Figure 2 Number of COPD patients in the whole study group with comorbid heart disease in 2003 and 2012.

Between baseline and follow-up, 299 patients died, and another 229 patients did not complete the second questionnaire due to other reasons. An attrition analysis showed that the deceased patients more often were from the oldest age group (P<0.001) and more often had comorbid heart disease (P<0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between non-responders and responders among patients alive in 2012 (data not shown).

Dyspnea

At baseline, mMRC scores were significantly higher for the group with heart disease at baseline (HD) and for those who later, during the study, developed heart disease (new HD) compared to those without a heart disease diagnosis (no HD) (). There was a significant increase in dyspnea symptoms during the study period for the groups with and without heart disease during the whole study period, but not for the new HD group (). The results of the logistic regression analysis for mMRC are presented in in . Comorbid heart disease during the whole study period (HD) was an independent statistically significant factor for a higher mMRC score at follow-up. After correction for baseline mMRC, no significant associations were found. Interaction analysis showed no effect modification by sex or age (data not shown). In the subgroup with available spirometry data, heart disease had no associations with the mMRC score (data not shown).

Table 2 Symptoms and health status 2005 and 2012

Table 3 Regression analyses with CCQ, CAT and mMRC ≥2 in 2012 as dependent variables

Health status

At baseline, CCQ scores were significantly higher for the group with HD and group with new HD (). Between 2005 and 2012 there was a statistically significant worsening of the mean CCQ, the mean CCQ symptoms, and mean CCQ functional state in the group of patients with no HD and in the group with new HD. No significant worsening was found in the patients with HD ().

Figure 4 Mean CCQ, total score and domains for 2005 and 2012 in COPD patients without heart disease (no HD), with heart disease diagnosed between 2003 and 2012 (new HD), and with heart disease at baseline (HD).

Abbreviation: CCQ, Clinical COPD Questionnaire.

The results of the linear regression analyses with the mean CCQ score and total CAT score as dependent variable are presented in . Both HD and new HD were, statistically, significantly associated with higher CAT and CCQ scores in unadjusted analysis. After adjustment for potential confounding factors, the association with CAT score remained for both HD and new HD, and the association with CCQ remained in the group with new HD. An association for HD was found in the unadjusted analysis of the CCQ symptoms domain and functional state. After adjustment for potential confounders, no association was found for the CCQ symptoms domain, but CCQ functional state showed an association with both HD and new HD. The CCQ mental state domain had no significant associations with heart disease (data not shown). After adjustment for baseline CCQ, no statistically significant associations of heart disease with worse health status, as assessed by CAT or CCQ, total and over all domains, over time were found. The interaction analyses showed no statistically significant effect modification by sex or age for any of the associations (data not shown). In the subgroup with available spirometry data, HD was, statistically, significantly associated with CCQ total, symptoms and functional state domain score and CAT in unadjusted analysis. In the adjusted regression analysis, only the association of heart disease during the whole study (HD) with CAT remained but disappeared after correction for baseline CCQ.

Discussion

The first main finding of this multicenter cohort study with 7-year follow up is that comorbid heart disease influenced health status in patients with COPD. The second main finding is that, in COPD, dyspnea and health status worsened over time, but comorbid heart disease did not accelerate this worsening.

Our finding that comorbid heart disease influenced the patients’ health status negatively has been described before in cross-sectional studies in this and other populations.Citation13,Citation22,Citation23 In our study, CAT was more influenced by comorbid heart disease than the CCQ score. This has been described for this study population before.Citation21 Health status was particularly worse for patients with HD and new HD in the CCQ functional state domain, which is consistent with a study where self-reported heart disease markedly reduced the functional state measured by 6 minutes walking distance and SGRQ.Citation24 We showed in our longitudinal study that this finding remains over time and the reduced functional state can be detected by using the CCQ questionnaire.

In analysis adjusted for confounders, mMRC was not significantly influenced by new HD, whereas HD was a significant factor for higher level of dyspnea. For the CCQ total score, the opposite was found. This might indicate that comorbid heart disease in the early stages mainly reduces functionality and not symptoms.

Our finding that comorbid heart disease did not accelerate the worsening in health status and dyspnea over time is consistent with findings of the ECLIPSE study.Citation25 The ECLIPSE study was performed over a period of 3 years on patients recruited from outpatient clinics, using self-reported heart trouble and health status assessed by SGRQ. We have expanded the findings from the ECLIPSE study as our study has a 7-year follow-up period, a patient population that is to a large extent selected in primary care and outcomes assessed by both mMRC, CAT and CCQ. This is an important finding because CAT is now mainly used for the assessment of COPD patients in daily practice.

We found a significant deterioration in health status of patients without heart disease, but not for those with a heart disease diagnosis during the whole study. The mean change in CCQ did not, however, exceed the minimal clinical difference of 0.4. The smaller deterioration for the HD group might be explained by regression towards the mean; Patients with heart disease already had such poor scores at baseline that worsening was less possible. Another reason could be that the care for heart disease has improved markedly in the last decade and is more structured and prioritized, which even benefits the care for comorbid COPD. It might even be possible that medication used for treating heart disease protects the lungs also. A meta-analysis of observational studies on the effect of beta-blockers on COPD outcome found that this medication reduces mortality and exacerbations in COPD patients.Citation26 A similar meta-analysis for statins showed that statins might improve exercise tolerance, lung function, and health status in COPD patients.Citation27

Interestingly, we found that patients who were diagnosed with heart disease later during the study showed a worse health status and symptom burden already at baseline, with a significant worsening during follow-up. This might indicate the presence of unrecognized comorbid heart disease at baseline. In this real-life study, the measure of heart disease is based on routine diagnoses rather than screening. It is known that heart disease is underdiagnosed in patients with COPD and our findings in the group with new HD suggest that this is also the case in this study population.Citation9,Citation28 It has previously been shown that a high SGRQ score is associated with extrapulmonary comorbidity in patients with mild to moderate air flow limitation.Citation29 It is clinically important to be observant for heart disease and other comorbidities when there is a marked discordance between the health status scores and FEV1%pred in a patient.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is that the longitudinal design of this study makes it possible to identify the group of patients who develop heart disease during the study period and retrospectively look at their health status and symptoms at baseline. Another strength of this study is its generalizability to clinical practice due to its multicenter design, including patients from both primary and secondary care. The fact that that spirometry data were not available for the whole study population and patients were selected based on the doctor’s diagnosis represents clinical reality in primary health care, where spirometry is not regularly repeated in the management of COPD.Citation30

A limitation, however, is that the group with incident HD was rather small and inhomogeneous. It is unknown when exactly these patients were diagnosed during the study period and there is a 2-year period between the record review and completion of the questionnaires. Nevertheless, our results show that comorbid heart disease worsens health status in early stages, even before the clinical diagnosis.

Another limitation is that CAT was not available in 2005 and we, therefore, have no data on CAT scores at baseline. CAT is recommended by GOLD for assessment of patients with COPD, and we found it important to be able to look at this instrument and the association with heart disease over time. Prior research has found that CCQ and CAT correlate well with each other and the SGRQ, and that comorbid heart disease is associated with both instruments.Citation21,Citation31 The CCQ at baseline can, therefore, be a valid alternative for CAT at baseline in the logistic regression analysis.

Finally, the loss of patients during follow-up could potentially cause a selection bias. It has been shown that high CCQ scores predict mortality.Citation32 In this study, the population with heart disease had a higher level of dyspnea and worse health status at baseline, and attrition analysis showed that the all-cause mortality was higher in this group. We cannot exclude the possibility that the absence of a longitudinal association between dyspnea and health status with comorbid heart disease is caused by the fact that patients with comorbid heart disease were overrepresented among those who died during the study period.

Conclusion

Comorbid heart disease contributes to lower health status and higher symptom burden in COPD. However, heart disease does not accelerate the worsening of symptoms and health status over time. In COPD management, it is important to optimize treatment of cardiovascular comorbidity to maintain or improve health status and to be observant for comorbid heart disease, especially when low health status and symptom burden cannot be explained by poor lung function alone.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating centres, and Ulrike Spetz-Nyström and Eva Manell for reviewing the patient records. A part of the results of this study were presented at the Swedish National Conference for General Practitioners in April 2018 and the Congress of the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) in Porto in May 2018.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HalbertRJNatoliJLGanoABadamgaravEBuistASManninoDMGlobal burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysisEur Respir J200628352353216611654

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) [homepage on the Internet]Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD 2018 [Internet] Available from: http://goldcopd.orgAccessed March 20, 2018

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRGarnhamRJonesPWWedzichaJAUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax199954758158610377201

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD Assessment TestEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- van der MolenTWillemseBWSchokkerSTen HackenNHPostmaDSJuniperEFDevelopment, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD QuestionnaireHealth Qual Life Outcomes200311312773199

- ChenWThomasJSadatsafaviMFitzgeraldJMRisk of cardiovascular comorbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysisLancet Respir Med20153863163926208998

- PutchaNDrummondMBWiseRAHanselNNComorbidities and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, influence on outcomes, and managementSemin Respir Crit Care Med201536457559126238643

- KaszubaEOdebergHRåstamLHallingAHeart failure and levels of other comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a Swedish population: a register-based studyBMC Res Notes2016921527067412

- RuttenFHCramerMJGrobbeeDEUnrecognized heart failure in elderly patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Heart J200526181887189415860516

- Van EedenSLeipsicJPaul ManSFSinDDThe relationship between lung inflammation and cardiovascular diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med20121861111622538803

- SmithMCWrobelJPEpidemiology and clinical impact of major comorbidities in patients with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2014987188825210449

- GuptaNPintoLMMoroganABourbeauJThe COPD assessment test: a systematic reviewEur Respir J201444487388424993906

- SundhJStällbergBLisspersKMontgomerySMJansonCCo-morbidity, body mass index and quality of life in COPD using the Clinical COPD QuestionnaireCOPD20118317318121513436

- SundhJMontgomerySHasselgrenMChange in health status in COPD: a seven-year follow-up cohort studyNPJ Prim Care Respir Med2016261607327763623

- OgaTNishimuraKTsukinoMSatoSHajiroTMishimaMLongitudinal deteriorations in patient reported outcomes in patients with COPDRespir Med2007101114615316713225

- SpencerSCalverleyPMSherwood BurgePJonesPWISOLDE Study GroupInhaled Steroids in Obstructive Lung Disease. Health status deterioration in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2001163112212811208636

- WackerMEHungerMKarraschSHealth-related quality of life and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in early stages – longitudinal results from the population-based KORA cohort in a working age populationBMC Pulm Med20141413425107380

- Standardized lung function testingReport working partyBull Eur Physiopathol Respir198319Suppl 51956616097

- van der MolenTDiamantZKocksJWTsiligianniIGThe use of health status questionnaires in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in clinical practiceExpert Rev Respir Med20148447949124894492

- AlmaHde JongCJelusicDHealth status instruments for patients with COPD in pulmonary rehabilitation: defining a minimal clinically important differenceNPJ Prim Care Respir Med2016261604127597571

- SundhJStällbergBLisspersKKämpeMJansonCMontgomerySComparison of the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and the Clinical COPD Questionnaire (CCQ) in a Clinical PopulationCOPD2016131576526367315

- de Miguel-DíezJCarrasco-GarridoPRejas-GutierrezJThe influence of heart disease on characteristics, quality of life, use of health resources, and costs of COPD in primary care settingsBMC Cardiovasc Disord201010820167091

- PatelARCDonaldsonGCMackayAJWedzichaJAHurstJRThe impact of ischemic heart disease on symptoms, health status, and exacerbations in patients with COPDChest2012141485185721940771

- Black-ShinnJLKinneyGLWiseALCardiovascular disease is associated with COPD severity and reduced functional status and quality of lifeCOPD201411554655124831864

- MillerJEdwardsLDAgustíAComorbidity, systemic inflammation and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohortRespir Med201310791376138423791463

- DuQSunYDingNLuLChenYBeta-blockers reduced the risk of mortality and exacerbation in patients with COPD: a meta-analysis of observational studiesPLoS One2014911e11304825427000

- ZhangWZhangYLiCWJonesPWangCFanYEffect of statins on COPD: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsChest201715261159116828847550

- BrekkePHOmlandTSmithPSøysethVUnderdiagnosis of myocardial infarction in COPD – Cardiac Infarction Injury Score (CIIS) in patients hospitalised for COPD exacerbationRespir Med200810291243124718595681

- LeeHJhunBWChoJDifferent impacts of respiratory symptoms and comorbidities on COPD-specific health-related quality of life by COPD severityInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017123301331029180860

- ArneMLisspersKStällbergBHow often is diagnosis of COPD confirmed with spirometry?Respir Med2010104455055619931443

- TsiligianniIGvan der MolenTMoraitakiDAssessing health status in COPD. A head-to-head comparison between the COPD assessment test (CAT) and the clinical COPD questionnaire (CCQ)BMC Pulm Med2012122022607459

- SundhJJansonCLisspersKMontgomerySStällbergBClinical COPD Questionnaire score (CCQ) and mortalityInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012783384223277739