Abstract

Background

This study examines the effects of the COPD-specific health promoting self-management intervention “Better living with COPD” on different self-management-related domains, self-efficacy, and sense of coherence (SOC).

Methods

In a randomized controlled design, 182 people with COPD were allocated to either an intervention group (offered Better living with COPD in addition to usual care) or a control group (usual care). Self-management-related domains were measured by the Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ) before and after intervention. Self-efficacy was measured by the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) and SOC was measured by the 13-item Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC-13). Effects were assessed by ANCOVA, using intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and per-protocol analysis (PPA).

Results

The PPA and the ITT analysis showed significant positive changes on Constructive attitudes and approaches (heiQ) (ITT: P=0.0069; PPA: P=0.0021) and Skill and technique acquisition (heiQ) (ITT: P=0.0405; PPA: P=0.0356). Self-monitoring and insight (heiQ) showed significant positive change in the PPA (P=0.0494). No significant changes were found on the other self-management domains (heiQ), self-efficacy (GSE), or SOC (SOC-13).

Conclusion

Better living with COPD had a significant positive short-term effect on some self-management-related domains, and could be an intervention contributing to the support of self-management in people with COPD. However, further work is needed to establish the clinical relevance of the findings and to evaluate the long-term effects.

Introduction

COPD is characterized by persistent airflow limitation and respiratory symptoms, due to abnormalities in airways and/or the alveolus, and is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide.Citation1,Citation2 The disease is common, preventable, and treatable,Citation2 and individuals living with COPD must make daily decisions regarding their own care; thus, self-management is an essential part of living with COPDCitation3,Citation4 and essential for the health care system’s efficiency and effectiveness.Citation5 Still, previous studies suggest that individuals’ management of COPD is often far from optimal.Citation6–Citation8

Various self-management support interventions (SMIs) have been developed to facilitate adequate self-management of COPD.Citation9,Citation10 However, agreement on the definition of SMIs has previously been lacking,Citation11 although their multifaceted nature and emphasis on enhancing people’s active roles and responsibilities have been highlighted.Citation12 Recent guidelines state that SMIs for people with COPD are “structured but personalized and often multi-component interventions, with goals of motivating, engaging and supporting the participants to positively adapt their behavior(s) and develop skills to better manage their disease”.Citation13,Citation14 SMIs should provide information,Citation12 elicit personalized goals, formulate appropriate strategies, and focus on intrinsic processes (eg, motivation, resource utilization, coping, and self-efficacy),Citation11,Citation13–Citation15 and mental health.Citation10 Furthermore, behavior change techniques are recommended to elicit participants’ motivation, confidence, and competence.Citation14

Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of COPD-specific multicomponent SMIs in primary care show positive effects of SMIs, such as a reduced number of unscheduled physician visitsCitation16 and COPD-related hospital admissions,Citation9,Citation12,Citation17 reduced emotional distress,Citation16,Citation17 improved health-related quality of life (HRQoL),Citation9 and increased self-efficacy.Citation16 Two other systematic and integrative reviewsCitation18,Citation19 reported less dyspnea,Citation18 changed health care utilization,Citation18,Citation19 and improved HRQoL in people who have undergone SMIs.Citation18,Citation19 However, some studies included in the reviewsCitation12,Citation16–Citation19 contain supervised exercises. This exceeds support levels coherent with SMIs in COPDCitation11 and makes it difficult to distinguish between the effects of the SMI and those of the exercise component. Furthermore, SMIs can have a specified salutogenic orientation and/or use motivational interviewing (MI) techniques. A study by Benzo et alCitation20 concludes that the use of MI may increase a person’s commitment and engagement in self-management and be feasible for people living with COPD, and evidence from related health care settings indicates that the use of a salutogenic orientation may be feasible and effective.Citation21

Few studies have examined the effects of COPD-specific SMIs on self-management-related abilities or behavior. One study’s effects include improved skill and technique acquisition, improved self-monitoring and insight, and more constructive attitudes and approaches.Citation22 Studies have also found better adherence to inhalation treatment and techniques,Citation23 increased smoking cessation,Citation24 improved knowledge of COPD,Citation23–Citation25 improved identification and treatment of exacerbations,Citation23 and improved activation for self-managementCitation22 in those who have undergone COPD-specific SMIs.

The importance of integrating SMIs in the primary care setting has been increasingly accentuated.Citation3,Citation26 In this study, we have developed a structured and salutogenic oriented health-promoting COPD-specific SMI, named Better living with COPD,Citation27 for implementation in local municipal health services. Our hypothesis is that Better living with COPD would improve different self-management-related domains, general self-efficacy, and sense of coherence (SOC).

Material and methods

Design and participants

This randomized controlled trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identification: NCT2479841) examines the effects of Better living with COPD on eight self-management-related domains (primary outcomes), general self-efficacy and SOC (secondary outcomes) in a parallel design, with a baseline measure (before randomization) and a follow-up measure 1–2 weeks after the intervention period. We expected that different self-management-related domains would be improved, but general self-efficacy and SOC are rather stable personal characteristics,Citation29–Citation31 therefore it is possible that the time frame (a few weeks after the intervention period) might be too short to see changes in general self-efficacy and SOC.

Participants with COPD from eleven municipalities on the west coast of Norway were recruited from a hospital register with the following inclusion criteria: registered ICD-10 code J44.0, 1, 8, or 9 after January 1, 2010; age ≥18 years; confirmed COPD grade II–IV, according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD);Citation32 and the ability to read and speak Norwegian. Exclusion criteria were substantial cognitive impairment reported in a medical journal (eg, severe dementia, severe Alzheimer’s disease), substantial alcohol and/or drug abuse, or a life expectancy <12 months due to comorbidity. Evaluation of fulfillment of inclusion and exclusion criteria was conducted by a research nurse and a lung specialist in collaboration.

The Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ) was considered the primary outcome, and a sample power for a two-sample t-test (individual randomization), with a suggested effect size of 0.50 (Cohen’s d), a significance level of 0.05, and 80% power, together with an allowed 20% attrition rate, resulted in the inclusion of a minimum of 154 participants.

Allocation, randomization, and procedures

The allocation ratio was 1:1. Included participants were given a running number (based on the alphabetical order of last names), and then the numbers were randomized by a statistician (using MATLABCitation33) with no access to the participant list. However, the geographically varying recruitment for a group intervention led to challenges with the allocation. Based on previous research,Citation34 the minimum group size was set to five participants, and as an attrition of 20% was expected, this indicates that at a minimum of six participants were to be allocated to each group. In municipalities with fewer than 12 registered participants, it was therefore not possible to establish two groups, and we decided to allocate one group to either intervention or control. In the larger municipalities, participants were allocated individually to the groups. The participants were randomly assigned to groups of ten within the municipality, and then the groups were randomized to either intervention or control, whereas participants from municipalities with only one group were randomized to either intervention or control at the municipality level. In total, 61 participants from six municipalities were randomized at the municipality level, whereas 121 participants were individually randomized. Of the 182 study participants, 92 were randomized to an intervention group and 90 to a control group. Those randomized to an intervention group were offered Better living with COPD in addition to usual care, whereas those randomized to a control group received usual care, although they were informed that they would be offered the intervention ~6 months later.

Participants were recruited between February and June 2015. Questionnaires including demographic and clinical characteristics were measured at baseline (inclusion), whereas the self-management-related domains, general self-efficacy, and SOC were measured at baseline and follow-up. The questionnaires were sent by post, and one reminder was sent out after ~3 weeks in cases with no response.

All participants received an information letter about the study before agreeing to participate and were informed of their allocation in a separate letter after randomization. The study was approved by the Regional Committee of Medical Research Ethics (reference no 2013/1741), and all participants gave written informed consent.

Intervention

The SMI, Better living with COPD, aimed to increase the participants’ consciousness of their potential, their internal and external resources and their abilities to use them, and thus to improve their self-management capabilities in the context of everyday living. A salutogenic orientation was incorporated into the group conversations. This orientation included a focus on SOC; understanding, manageability, and meaningfulness, and on emphasizing health as a continuum, the person’s history, the understanding of tension and strain as potentially health promoting, resources for health, and active adaption,Citation34,Citation35 as described by Langeland et al.Citation36,Citation37 MI,Citation38–Citation40 congruent with improvement in self-efficacy,Citation41,Citation42 enhanced activation for self-management,Citation42 and a salutogenic approach,Citation43 was used as a communication technique.

The intervention consists of weekly 2-hour-long group conversations over 11 weeks.Citation44 The face-to-face conversations took place in meeting locations in the participants’ home municipalities. The sessions started with participants discussing their everyday life experiences. The next part was related to topics initiated by conversations based on reflected notes (homework) related to those topics, voluntarily prepared by the participants. Themes such as problem solving, goal setting, symptoms, social challenges, physical activity, nutrition, medication, smoking cessation, exacerbations, and psychological issues were covered.Citation27 A small booklet with information and advice about physical activity, nutrition, dyspnea, and health care resources was handed out during the SMICitation45 in addition to a general COPD action plan draft.Citation46 Each session followed a similar structure,Citation27,Citation36 albeit customized according to group dynamics and participants’ needs. From this, the intervention was delivered as planned, but with some variation due to differences in group dynamics.

All group sessions were planned to be moderated by two moderators. The main moderator was a registered nurse (RN) with special competence in COPD care,Citation47 salutogenesis, self-efficacy, and MI. In addition, the main moderator had initial training in the intervention and had previously co-moderated Better living with COPD with the first author. An RN and/or a physiotherapist from the participant’s home municipality participated as co-moderator.

Usual care

The Norwegian guidelines for care and treatment of people with COPD include specific criteria regarding frequency of visits to a general practitioner, smoking cessation, physiotherapy, nutritional advice, and pulmonary rehabilitation.Citation48 Although it is possible that “usual care” varies between municipalities,Citation49,Citation50 the Norwegian health care system is mainly based on public funding and a principle of universal access regardless of residential area.Citation51 Therefore, no precautions were taken in this study to ensure equality in usual care.

Measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Age and sex were obtained from the hospital register, whereas education, cohabitation, comorbidity, and years diagnosed with COPD were self-reported.

Lung function

For participants with spirometry conducted according to international standardsCitation52,Citation53 less than 12 months prior to enrollment, data on post-bronchodilator FVC and FEV1 were obtained from medical records. For participants with the last spirometry registered more than 12 months prior to enrollment, a new spirometry was conducted according to international standards.Citation52,Citation53 To calculate FEV1 percentage predicted (FEV1% predicted), Norwegian reference values were used.Citation54 COPD disease severity was classified using GOLD criteriaCitation2: moderate (II), severe (III), or very severe (IV), defined as FEV1/FVC <0.7 and FEV1% 50%–79% (II), FEV1% 30%–49% (III), or FEV1% <30% (IV).Citation2

Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnoea Scale

The mMRCCitation48,Citation55 Dyspnoea Scale was used to measure dyspnea. This measure asks people to rate dyspnea by choosing the statement best describing when dyspnea occurs. Different statements describing decreasing levels of physical activity that may precipitate shortness of breath are presented on a five-point scale (range 0–4), with higher scores indicating more severe dyspnea.Citation2,Citation55 The mMRC Dyspnoea Scale has shown satisfactory reliability and validity.Citation56–Citation58

COPD Assessment Test (CAT)

To measure COPD symptom burden, the CATCitation59 was used. The CAT consists of eight items (cough, phlegm, chest tightness, breathlessness, activities, confidence, sleep, and energy) rated on a 0–5 scale. The total score range is 0–40, with a higher score indicating a higher symptom burden.Citation59–Citation61 The CAT has shown satisfactory reliability and validity.Citation59,Citation60,Citation62,Citation63

Self-management

HeiQ, version 2.0,Citation28,Citation64 was used to measure eight self-management-related domains: 1) Positive and active engagement in life; 2) Health directed activities; 3) Skill and technique acquisition; 4) Constructive attitudes and approaches; 5) Self-monitoring and insight; 6) Health service navigation; 7) Social integration and support; and 8) Emotional distress. HeiQ comprises 40 items, scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree).Citation28,Citation64 Domain scores are calculated by adding the score of items within scales and dividing by the number of items; consequently, all domain scores range between 1 and 4. Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-management ability for all domains, except for the Emotional distress domain, where a higher score indicates more emotional distress. This generic questionnaire has shown satisfactory validity and reliability across diverse settings,Citation28,Citation64–Citation67 and has been used in studies including people with COPD.Citation22,Citation68,Citation69 Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.63 (Health service navigation) to 0.90 (Emotional distress).

General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE)

The GSE was used to measure self-efficacy. The GSE is a ten-item scale designed to assess perceived general self-efficacy.Citation70–Citation72 Each item is scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (exactly true), generating a sum score ranging from 10 to 40. Higher scores indicate higher self-efficacy.Citation70,Citation71 Up to two responses (20%) were allowed to be missing and were replaced by the mean value of the person’s valid scores.Citation73 The GSE has been used in studies including people with COPD,Citation73,Citation74 and has shown satisfactory reliability and validity.Citation30,Citation70,Citation71,Citation73,Citation75

Sense of Coherence Scale-13 (SOC-13)

SOC was measured using the SOC-13.Citation29 The SOC-13 is a 13-item short form of the original 29-item Orientation to Life Questionnaire.Citation29 Each item is rated on a seven-point Likert scale, where the most common anchor points are “never” and “very often”.Citation29 The items cover comprehensibility (five items), manageability (four items), and meaningfulness (four items), generating a total sum score ranging from 13 to 91. Higher scores indicate stronger SOC.Citation70 The SOC-13 has satisfactory reliability and validity,Citation76–Citation80 and has been used in previous COPD studies.Citation81,Citation82 In this study, missing data were substituted separately for individuals who answered at least 75% of the items for each component.

Data handling and statistical analysis

Missing data were a problem in the collected data. We used the observed data for all descriptive analyses. For the inference, we used multiple imputation with 50 imputed data sets.Citation83 The imputation was based on information about heiQ, age, sex, education, FEV1% predicted, GSE, and SOC-13. Data were blinded during the analyses, ie, the groups were labeled with non-identifying terms.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. The SMI effect on each heiQ domain, GSE, and SOC-13 was assessed by an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), ie, a linear model for the follow-up measurement of each outcome depending on intervention type and adjusted for its baseline measure. All models were estimated using intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and per-protocol analysis (PPA). The ITT analysis was conducted for all available data, while inclusion in the PPA required participants to follow the protocol sufficiently; ie, we included in the PPA all participants who had participated in more than half of the group conversations. The general significance level was set to 0.05. All descriptive computations were conducted using SPSS 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), whereas the imputation and inference (ANCOVA) were carried out using R 3.4Citation84 with the package mice 2.46.Citation85

Results

Participants’ characteristics

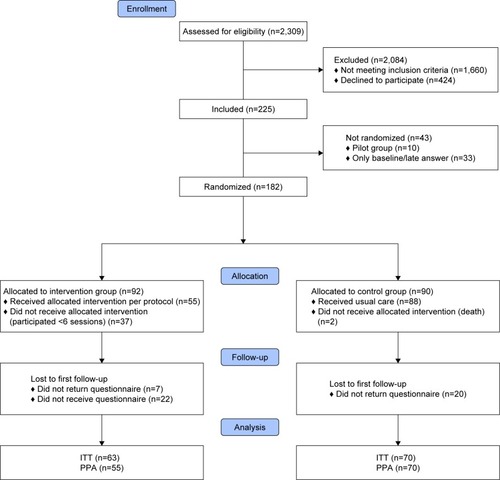

Of the 649 people invited to participate, 225 (34.7%) consented (baseline). Of these, 43 were excluded; ten were allocated to a pilot study and 33 either withdrew from further participation before randomization or responded post-randomization (). Consequently, 182 participants were included in this study. The attrition rate was 22.2% in the control group and 31.5% in the intervention group (ITT).

Figure 1 Overview of recruitment, allocation, and randomization.

Participants’ characteristics at baseline are shown in . Self-monitoring and insight (heiQ) had the highest mean ± SD score at 3.03±0.35, whereas Health directed activities (heiQ) had the lowest mean score at 2.63±0.63. The mean score for Emotional distress (heiQ) was 2.38±0.62, and the mean scores for self-efficacy (GSE) and SOC (SOC-13) were 25.97±6.42 and 64.59±9.64, respectively.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants at baseline

Effects of Better living with COPD

As shown in , both PPA and ITT analysis showed significant positive changes on Constructive attitudes and approaches (heiQ) (PPA: P=0.0021, d=0.38; ITT: P=0.0069, d=0.32) and Skill and technique acquisition (heiQ) (PPA: P=0.0405, d=0.17; ITT: P=0.0356, d=0.17). While the estimated effect on Constructive attitudes and approaches (heiQ) was slightly higher using the PPA [mean change difference (95% CI) PPA: 0.16 (0.03 to 0.30) vs ITT: 0.14 (0.00 to 0.27)], the effect on Skill and technique acquisition (heiQ) [PPA: 0.06 (−0.07 to 0.19); ITT: 0.06 (−0.06 to 0.19)] was similar for both. In addition, the PPA indicated a significant positive change in self-monitoring and insight (heiQ) [P=0.0494, d=0.15, mean change difference (95% CI): 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.18)], although this was not significant in the ITT analysis (). The changes found in the other self-management domains were insignificant (P≥0.0944), as were the changes in general self-efficacy (GSE) and SOC (SOC-13) (P≥0.1814).

Table 2 Effects of better living with COPD (primary outcomes) evaluated by PPA and ITT analysis, ANCOVA: means from baseline and follow-up, mean change difference and effect size

Discussion

Better living with COPD had a significant positive effect on Constructive attitudes and approaches in both PPA and ITT analysis. Constructive attitudes and approaches covers the important shift in how people view the impact of their condition on their lives, positive attitude, and sense of control and empowerment.Citation28,Citation64 Our finding is supported by a longitudinal study that found improvement in Constructive attitudes and approaches after a similar group-based SMI.Citation22 Together, these findings suggest that participation in SMIs could improve Constructive attitudes and approaches for people with COPD. Although the effect size is larger in the PPA (d=0.38), the ITT analysis (d=0.32) better reflects the clinical effect.Citation86,Citation87 An effect size of 0.32 is considered small, according to Cohen,Citation88 but is higher than the estimated benchmark effect sizes for change in Constructive attitudes and approaches, varying from 0.19 to 0.21.Citation67 The salutogenic orientation of Better Living with COPD could be one explanation for the positive effect on Constructive attitudes and approaches. A salutogenic orientation focuses on health as a continuum, the person’s history, active adaption, and salutary factors, and stressors are seen as possibly salutary,Citation29,Citation36,Citation37,Citation89 and may have contributed to a shift in participants’ attitudes and approaches.

Better living with COPD also had a positive effect on Skill and technique acquisition, significant in both PPA and ITT analysis. The Skill and technique acquisition scale captures knowledge-based skills and techniques related to managing disease-related symptoms and health problems, including the use of particular aids,Citation28 and our finding is supported by Turner et al.Citation22 Inhalation techniques are important skills and techniques related to medication adherence in COPD.Citation13,Citation90 However, incorrect inhalation techniques are common,Citation13,Citation91,Citation92 and inhalation techniques were therefore specifically addressed as a topic in one group session. As a result of this, a surprising finding was the small effect size (d=0.17) in Skill and technique acquisitions. One possible explanation may be related to the group-based intervention. Previous research suggests that repeating education and teach-back approaches are recommended,Citation93–Citation95 but in Better living with COPD, inhalation techniques were specifically addressed at one group session, and a teach-back approach was not mandatory for participants. Another possible explanation could be that inhalation techniques were not what participants had in mind when responding to the generic items in the Skill and technique acquisition scale.Citation28

Furthermore, a significant positive effect of Better living with COPD was also found in the PPA for Self-monitoring and insight (P=0.0494). This is in accordance with the findings in the longitudinal study by Turner et al.Citation22 Still, the effect size in this study (d=0.15) was smaller than the estimated benchmark effect sizes for change in this domain in chronic diseases in general.Citation67 Also, the benchmark sizes presented for changes in heiQ scores are not benchmark sized for clinical relevance.Citation67 Therefore, the clinical relevance of the improvements found on Self-monitoring and insight, as well as on the Constructive attitudes and approaches and Skill and technique acquisition domains, is uncertain.

No significant effects were found on Positive and active engagement in life, Health directed activities, Health service navigation, Social integration and support, or Emotional distress. Previous randomized controlled studies including participants with chronic conditions have reported effects of various SMIs on one or more of these domains.Citation96–Citation98 However, differences between the SMIs, the context, and the participants make direct comparisons difficult, and possible explanations for our findings are multiple. For example, in accordance with models clarifying COPD-specific SMIs,Citation11 Better living with COPD did not include supervised physical training. However, previous studies on pulmonary rehabilitation programs found the frequency and duration of supervised training to be crucial to increasing physical activity levels,Citation99 and items related to physical activity are included in the Health directed activities domain of heiQ.Citation28 Our findings could therefore suggest that support of some self-management-related domains could be better met by means additional to the ones included in Better living with COPD (eg, supervised physical training and individual teach-back methods).

In addition, the changes found in general self-efficacy and SOC were insignificant. The self-management-related domains are described as proximal outcomes of SMIs,Citation28 but because self-efficacy and SOC are relatively stable personal characteristics,Citation29–Citation31 change may need time to develop. This is in line with descriptions of general self-efficacy and SOC as more distal outcomes of SMIs.Citation28 The post-intervention scores were measured shortly after the intervention period, and it is possible that the time frame was too short to detect developing changes in these characteristics. Further work including long-term evaluations is warranted.

Some methodological remarks should be mentioned. Three different nurses were the main group moderators and participants were actively involved in the conversations, leading to possible differences in group dynamics. Although group moderators had education before the SMI, their experience with a specific salutogenic orientation varied, and none had previous experience using MI in group contexts. This may have introduced additional variance, possibly reflecting variance in a real-life clinical implementation, but the effects may have been weaker than with experienced group moderators. The response rate was low, although similar to another study of self-management (cross-sectional),Citation100 but slightly lower than the response rate in another comparable study with inclusion criteria from a hospital register using postal mail.Citation101 A low response rate may increase the risk of volunteer bias. The baseline measurement was performed before randomization, but since participants could not be further blinded, desirability bias could account for some changes in the intervention group. Knowledge of group assignment may affect participants’ responses to outcome measures and their behavior in the trial.Citation102 Yet, this bias may have been reduced by the control group’s expectation of being offered the intervention after the study and possible activation following their knowledge of future SMI participation. Being informed that they would be offered the intervention after ~6 months could have had an impact on participants’ experience of the usual care provided.Citation103 In addition, this study only explored short-term effects possibly affected by positive experiences in the group conversations. Long-term effects as well as prognostic or predictive factors are yet to be investigated. It is also possible that we had easier access to participants through hospital registers, and inclusion may differ in clinical practice. Previous studies suggest that SMIs may be hampered by challenges faced in real-world clinical settings, such as referrers’ lack of enthusiasm.Citation104

One study limitation is that the follow-up measurements were limited because of a clerical error, where 22 intervention group participants did not receive follow-up questionnaires () after leaving the groups. This introduced unnecessary missing data in the ITT analysis. Unfortunately, we lack sufficient information to determine whether this affected the results, although there were no significant differences between these 22 and other participants at baseline on any of the self-management-related domains. This error also made it difficult to evaluate the attrition rate for those allocated to an intervention group, but the attrition rate was slightly higher (22.2%) than the estimated 20% for those allocated to a control group. In addition, we had to adapt the randomization procedure because of unexpectedly few participants in smaller municipalities, leading to a lower power than planned and a potential for introducing confounding variables owing to possible differences in services between the municipalities. The first author’s participation in the SMIs could also raise methodological issues.

Conclusion

No randomized controlled studies have previously evaluated the effects of a salutogenic oriented SMI for people with COPD on the eight self-management-related domains, self-efficacy, and SOC specified in this study, and this study significantly adds to the knowledge of effects of disease-specific and health-promoting SMIs in COPD. Better living with COPD had significant positive effects on some self-management-related domains (Constructive attitudes and approaches, Skills and technique acquisition, and Self-monitoring and insight), whereas no significant effects were found on the other domains, general self-efficacy, and SOC. Therefore, Better living with COPD may serve as one of several means of self-management support, but further work is necessary to establish possible long-term effects of Better living with COPD on the specified domains and to evaluate possible long-term effects on SOC and self-efficacy.

Data sharing statement

Participant data (sociodemographic variables [age, sex, and GOLD grade] and the eight heiQ domains) used in the analysis in this study, together with a complementary specification of the intervention, “Better living with COPD” (in Norwegian), can be obtained on direct request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr Gunnar Egge for his contribution in planning and feasibility testing the intervention, and the municipalities for providing meeting locations and staff. This work was supported by the Western Norway Regional Health Authority [grant number 2013/911836] and the Norwegian Extra Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation [grant number 2015/RB13639].

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- López-CamposJLTanWSorianoJBGlobal burden of COPDRespirology2016211142326494423

- GOLDGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease2018 Available from: http://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/Accessed March 26, 2018

- BodenheimerTLorigKHolmanHGrumbachKPatient self-management of chronic disease in primary careJAMA2002288192469247512435261

- LorigKRHolmanHSelf-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanismsAnn Behav Med20032611712867348

- HolmanHLorigKPatient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic diseasePublic Health Rep2004119323924315158102

- RoglianiPOraJPuxedduEMateraMGCazzolaMAdherence to COPD treatment: Myth and realityRespir Med201712911712328732818

- BryantJMcDonaldVMBoyesASanson-FisherRPaulCMelvilleJImproving medication adherence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic reviewRespir Res201314110924138097

- SriramKBPercivalMSuboptimal inhaler medication adherence and incorrect technique are common among chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patientsChron Respir Dis2016131132226396159

- LenferinkABrusse-KeizerMvan der ValkPDSelf-management interventions including action plans for exacerbations versus usual care in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20178CD01168228777450

- NewhamJJPresseauJHeslop-MarshallKFeatures of self-management interventions for people with COPD associated with improved health-related quality of life and reduced emergency department visits: a systematic review and meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2017121705172028652723

- WaggKUnravelling self-management for COPD: what next?Chron Respir Dis2012915722308549

- JonkmanNHWestlandHTrappenburgJCDo self-management interventions in COPD patients work and which patients benefit most? An individual patient data meta-analysisInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016112063207427621612

- GOLDGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease2017 Available from: http://goldcopd.orgAccessed September 3, 2017

- EffingTWVercoulenJHBourbeauJDefinition of a COPD self-management intervention: International Expert Group consensusEur Respir J2016481465427076595

- van HooftSMBeen-DahmenJMJIstaEvan StaaABoeijeHRA realist review: what do nurse-led self-management interventions achieve for outpatients with a chronic condition?J Adv Nurs20177361255127127754557

- BakerEFatoyeFClinical and cost effectiveness of nurse-led self-management interventions for patients with copd in primary care: A systematic reviewInt J Nurs Stud20177112513828399427

- WangTTanJYXiaoLDDengREffectiveness of disease-specific self-management education on health outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysisPatient Educ Couns201710081432144628318846

- ZwerinkMBrusse-KeizerMvan der ValkPDSelf management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD002990

- JonsdottirHSelf-management programmes for people living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a call for a reconceptualisationJ Clin Nurs2013225–662163723398312

- BenzoRVickersKErnstDTuckerSMcEvoyCLorigKDevelopment and feasibility of a self-management intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease delivered with motivational interviewing strategiesJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev201333211312323434613

- PelikanJMThe Application of Salutogenesis in Healthcare SettingsMittelmarkMBSagySErikssonMThe Handbook of Salutogenesis ChamSpringer International Publishing2017261266

- TurnerAAndersonJWallaceLKennedy-WilliamsPEvaluation of a self-management programme for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseChron Respir Dis201411316317224980127

- Garcia-AymerichJHernandezCAlonsoAEffects of an integrated care intervention on risk factors of COPD readmissionRespir Med200710171462146917339106

- EfraimssonEOHillervikCEhrenbergAEffects of COPD self-care management education at a nurse-led primary health care clinicScand J Caring Sci200822217818518489687

- WaltersJCameron-TuckerHWillsKEffects of telephone health mentoring in community-recruited chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on self-management capacity, quality of life and psychological morbidity: a randomised controlled trialBMJ Open201339e003097

- Helse-og omsorgsdepartementetSt meld 47 (2008–2009) Sam-handlingsreformen. Rett behandling – på rett sted – til rett tid2009Norwegian Available from: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/doku-menter/stmeld-nr-47-2008-2009-/id567201/Accessed June 1, 2018

- BentsenSBBringsvorHBKallekodtJIversenESBedre liv med kols; utprøving av et helsefremmende egenomsorgsprogram for pasienter med kols i nærmiljøet der de borExtrastiftelsen2016Norwegian Available from: https://www.extrastiftelsen.no/prosjekter/bedre-liv-med-kols/Accessed June 18, 2018

- OsborneRHElsworthGRWhitfieldKThe Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ): an outcomes and evaluation measure for patient education and self-management interventions for people with chronic conditionsPatient Educ Couns200766219220117320338

- AntonovskyAUnraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay WellSan FranciscoJossey-Bass1987

- ScholzUDoñaBGSudSSchwarzerRIs general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countriesEur J Psychol Assess2002183242251

- SchwarzerRSelf-efficacy: Thought Control of ActionWashington DCHemisphere1992

- GOLDGlobal Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD2014 Available from: https://goldcopd.org/Accessed December 12, 2014

- MATLAB 9.0Natick, MAThe MathWorks, Inc

- AntonovskyAHealth, Stress, and CopingSan FranciscoJossey-Bass1979

- AntonovskyAUnravelling the Mystery of HealthSan FranciscoJossey-Bass1987

- LangelandEWahlAKKristoffersenKHanestadBRPromoting coping: salutogenesis among people with mental health problemsIssues Ment Health Nurs200728327529517454280

- LangelandERiiseTHanestadBRNortvedtMWKristoffersenKWahlAKThe effect of salutogenic treatment principles on coping with mental health problems: A randomised controlled trialPatient Educ Couns200662221221916242903

- RollnickSMillerWRWhat is Motivational Interviewing?Behav Cogn Psychother19952304325334

- WagnerCCIngersollKSMotivational Interviewing in GroupsNew YorkGuilford Press2013

- RollnickSMillerWRButlerCMotivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change BehaviorNew YorkGuilford Press2008

- LaneCButterworthSSpeckLMotivational interviewing groups for people with chronic health conditionsWagnerCCIngersollKSMotivational Interviewing in GroupsNew YorkGuilford Press2013314331

- LindenAButterworthSWProchaskaJOMotivational interviewing-based health coaching as a chronic care interventionJ Eval Clin Pract201016116617420367828

- HøjdahlTMagnusJHHagenRLangelandE“VINN”- An accredited motivational program promoting convicted women’s sense of coherence and copingEuro Vista201323177190

- BentsenSBLangelandEHolmALEvaluation of self-management interventions for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Nurs Manag201220680281322967298

- AlsakerTEggeGKnutsenBFLivet med kols – egeninnsats. Helse Fonna, Tysvær kommune, Landsforeningen for hjerte-og lungesyke & FOUSAM2014Norwegian Available from: http://www.helsetorg-modellen.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/kols_brosjyre.pdfAccessed June 12, 2018

- AlsakerTEggeGKnutsenBFLivet med kols – Egenbehandling-splan. Helse Fonna, Tysvær kommune, Landsforeningen for hjerte-og lungesyke & FOUSAM2014Norwegian https://helse-fonna.no/seksjon-behandling/documents/livet-med-kols-behandlingsplan.pdfAccessed June 12, 2018

- BerlandABentsenSBPatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in safe hands: An education programme for nurses in primary care in NorwayNurse Educ Pract201515427127625881490

- HelsedirektoratetKols Nasjonal faglig retningslinje og veileder for forebygging, diagnostisering og oppfølgingOsloHelsedirektoratet2012 Norwegian

- RiksrevisjonenThe Office of the Auditor General’s investigation of resource utilisation and quality in the health service following the introduction of the Coordination Reform. Document 3:52015–2016OsloOffice of the Auditor General of Norway2016 Norwegian

- RiksrevisjonenThe Office of the Auditor General’s investigation of public health work. Document 3:112014–2015OsloOffice of the Auditor General of Norway2015 Norwegian

- LindahlAKThe Norwegian Health Care System2015 Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2016_jan_1857_mos-sialos_intl_profiles_2015_v7.pdfAccessed January 24, 2018

- MillerMRHankinsonJBrusascoVStandardisation of spirometryEur Respir J200526231933816055882

- GOLDGlobal Institute for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, GOLD Spirometry Guide2010 Available from: https://goldcopd.org/gold-spirometry-guide/Accessed April 27, 2016

- JohannessenALehmannSOmenaasEREideGEBakkePSGulsvikAPost-bronchodilator spirometry reference values in adults and implications for disease managementAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006173121316132516556696

- FletcherCMStandardised questionnaire on respiratory symptoms: a statement prepeared and approved by the MRC Committee on the Aetiology of Chronic BronchitisBr Med J19602166513688719

- BestallJCPaulEAGarrodRGarnhamRJonesPWWedzichaJAUsefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax199954758158610377201

- StentonCThe MRC breathlessness scaleOccup Med2008583226227

- MahlerDAWellsCKEvaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspneaChest19889335805863342669

- JonesPWHardingGBerryPWiklundIChenWHKline LeidyNDevelopment and first validation of the COPD Assessment TestEur Respir J200934364865419720809

- JonesPWBrusselleGDal NegroRWProperties of the COPD assessment test in a cross-sectional European studyEur Respir J2011381293521565915

- KarlohMFleig MayerAMauriciRPizzichiniMMMJonesPWPizzichiniEThe COPD Assessment Test: What do we know so far?: A systematic review and meta-analysis about clinical outcomes prediction and classification of patients into GOLD stagesChest2016149241342526513112

- DoddJWHoggLNolanJThe COPD assessment test (CAT): response to pulmonary rehabilitation. A multicentre, prospective studyThorax201166542542921398686

- JonesPWHardingGWiklundITests of the responsiveness of the COPD assessment test following acute exacerbation and pulmonary rehabilitationChest2012142113414022281796

- WahlAKOsborneRHLangelandEMaking robust decisions about the impact of health education programs: Psychometric evaluation of the Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ) in diverse patient groups in NorwayPatient Educ Couns201699101733173827211224

- ElsworthGRNolteSOsborneRHFactor structure and measurement invariance of the Health Education Impact Questionnaire: Does the subjectivity of the response perspective threaten the contextual validity of inferences?SAGE Open Med20155http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2050312115585041Accessed April 2, 2018

- NolteSElsworthGROsborneRHAbsence of social desirability bias in the evaluation of chronic disease self-management interventionsHealth Qual Life Outcomes201311111423835133

- ElsworthGROsborneRHPercentile ranks and benchmark estimates of change for the Health Education Impact Questionnaire: Normative data from an Australian sampleSAGE Open Med20173235 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28560039Accessed June 1, 2018

- SchulerMMusekampGBengelJNolteSOsborneRHFallerHMeasurement invariance across chronic conditions: a systematic review and an empirical investigation of the Health Education Impact Questionnaire (heiQ™)Health Qual Life Outcomes2014125624758346

- BélangerAHudonCFortinMAmirallJBouhaliTChouinardM-CValidation of a French-language version of the health education impact Questionnaire (heiQ) among chronic disease patients seen in primary care: a cross-sectional studyHealth Qual Life Outcomes20151311925608461

- SchwarzerRGeneral Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE). [homepage on the Internet] [updated 2012, February 12]. Available from: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/selfscal.htmAccessed March 20, 2017

- SchwarzerREverything you want to know about the General Self-Efficacy Scale but were afraid to ask2014 Available from: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/faq_gse.pdfAccessed March 20, 2017

- SchwarzerRJerusalemMCausal and control beliefsWeinmanJWrightSJohnstonMMeasures in Health Psychology: A User’s PortfolioWindsorNFER-NELSON19953537

- AndenæsRBentsenSBHvindenKFagermoenMSLerdalAThe relationships of self-efficacy, physical activity, and paid work to health-related quality of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)J Multidiscip Healthc2014723924724944515

- BonsaksenTLerdalAFagermoenMSFactors associated with self-efficacy in persons with chronic illnessScand J Psychol201253433333922680700

- LegangerAKraftPRøysambERøysambEPerceived self-efficacy in health behaviour research: Conceptualisation, measurement and correlatesPsychol Health20001515169

- ErikssonMLindströmBValidity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: a systematic reviewJ Epidemiol Community Health200559646046615911640

- PallantJFLaeLSense of coherence, well-being, coping and personality factors: further evaluation of the sense of coherence scalePers Individ Dif20023313948

- SchnyderUBüchiSSenskyTKlaghoferRAntonovsky’s sense of coherence: trait or state?Psychother Psychosom200069629630211070441

- FeldtTLintulaHSuominenSKoskenvuoMVahteraJKivimäkiMStructural validity and temporal stability of the 13-item sense of coherence scale: prospective evidence from the population-based HeSSup studyQual Life Res200716348349317091360

- AntonovskyAThe structure and properties of the sense of coherence scaleSoc Sci Med19933667257338480217

- DelgadoCSense of coherence, spirituality, stress and quality of life in chronic illnessJ Nurs Scholarsh200739322923417760795

- LundmanBForsbergKAJonsénESense of coherence (SOC) related to health and mortality among the very old: the Umeå 85+ studyArch Gerontol Geriatr201051332933220171749

- van BuurenSFlexible Imputation of Missing DataNew YorkTaylor and Francis2012

- R Core TeamA language for statistical computing2017 Available from: https://www.r-project.org/Accessed April 17, 2018

- van BuurenSGroothuis-OudshoornKMice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in RJ Stat Softw2011453167

- RanganathanPPrameshCSAggarwalRCommon pitfalls in statistical analysis: Intention-to-treat versus per-protocol analysisPerspect Clin Res20167314414627453832

- GuptaSKIntention-to-treat concept: A reviewPerspect Clin Res20112310911221897887

- CohenJStatistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences2nd edHillsdale, NJLawrence Erlbaum1988

- LangelandEVinjeHFThe application of salutogenesis in mental healthcare settingsMittelmarkMBSagySErikssonMThe Handbook of SalutogenesisChamSpringer International Publishing2017299305

- BoniniMUsmaniOSThe importance of inhaler devices in the treatment of COPDCOPD Res and Practice2015 Available from: https://copdrp.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40749-015-0011-0Accessed June 18, 2018

- CromptonGKBarnesPJBroedersMThe need to improve inhalation technique in Europe: a report from the Aerosol Drug Management Improvement TeamRespir Med200610091479149416495040

- MelaniASBonaviaMCilentiVInhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease controlRespir Med2011105693093821367593

- KlijnSLHiligsmannMEversSRomán-RodríguezMvan der MolenTvan BovenJFMEffectiveness and success factors of educational inhaler technique interventions in asthma & COPD patients: a systematic reviewNPJ Prim Care Respir Med20172712428408742

- PothiratCChaiwongWPhetsukNPisalthanapunaSChetsadaphanNChoomuangWEvaluating inhaler use technique in COPD patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101291129826185435

- SanchisJCorriganCLevyMLViejoJLADMIT GroupInhaler devices – from theory to practiceRespir Med2013107449550223290591

- FrancisKLMatthewsBLVan MechelenWBennellKLOsborneRHEffectiveness of a community-based osteoporosis education and self-management course: a wait list controlled trialOsteoporos Int20092091563157019194641

- FortinMChouinardMCDuboisMFIntegration of chronic disease prevention and management services into primary care: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial (PR1MaC)CMAJ Open201644E588E598

- CrottyMPrendergastJBattersbyMWSelf-management and peer support among people with arthritis on a hospital joint replacement waiting list: a randomised controlled trialOsteoarthritis Cartilage200917111428143319486959

- CorhayJLDangDNVan CauwenbergeHLouisRPulmonary rehabilitation and COPD: providing patients a good environment for optimizing therapyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20149273924368884

- Bos-TouwenISchuurmansMMonninkhofEMPatient and disease characteristics associated with activation for self-management in patients with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure and chronic renal disease: a cross-sectional survey studyPLoS One2015105e0126400e012641525950517

- SridharMTaylorRDawsonSRobertsNJPartridgeMRA nurse led intermediate care package in patients who have been hospitalised with an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax200863319420017901162

- KaranicolasPJFarrokhyarFBhandariMBlinding: Who, what, when, why, how?Can J Surg201053534534820858381

- CunninghamJAKypriKMccambridgeJExploratory randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of a waiting list control designBMC Med Res Methodol20131315024314204

- AckermanINBuchbinderROsborneRHChallenges in evaluating an Arthritis Self-Management Program for people with hip and knee osteoarthritis in real-world clinical settingsJ Rheumatol20123951047105522382340