Abstract

Background

Several clinical studies suggest common underlying pathogenetic mechanisms of COPD and depressive/anxiety disorders. We aim to evaluate psychopathological and physical effects of aerobic exercise, proposed in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation, in a sample of COPD patients, through the correlation of some psychopathological variables and physical/pneumological parameters.

Methods

Fifty-two consecutive subjects were enrolled. At baseline, the sample was divided into two subgroups consisting of 38 depression-positive and 14 depression-negative subjects according to the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). After the rehabilitation treatment, we compared psychometric and physical examinations between the two groups.

Results

The differences after the rehabilitation program in all assessed parameters demonstrated a significant improvement in psychiatric and pneumological conditions. The reduction of BMI was significantly correlated with fat mass but only in the depression-positive patients.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that pulmonary rehabilitation improves depressive and anxiety symptoms in COPD. This improvement is significantly related to the reduction of fat mass and BMI only in depressed COPD patients, in whom these parameters were related at baseline. These findings suggest that depressed COPD patients could benefit from a rehabilitation program in the context of a multidisciplinary approach.

Keywords:

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression was ranked as the third leading cause of the global burden of disease in 2004 and will move into the first place by 2030. Worldwide, the fifth contributor to the burden of disease in 2020 is predicted to be COPD.Citation1,Citation2

As defined by American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS), COPD is a preventable and treatable disease state characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. The airflow limitation is usually progressive and is associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs to noxious particles or gases, primarily caused by cigarette smoking. It consists of the association of chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Chronic bronchitis is defined clinically as chronic productive cough for 3 months in each of 2 successive years in a patient in whom other causes of productive chronic cough have been excluded. Emphysema is defined pathologically as the presence of permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls and without obvious fibrosis.Citation3

Several clinical studies show high rates of anxiety (21%–96%)Citation4 and affective (mostly depressive) disorders (27%–79%) in COPD,Citation5,Citation6 which can affect prognostic evolution in terms of compliance, disability, and mortality.Citation7 It is not easy to diagnose depression in COPD patients because of overlapping symptoms between COPD and depression. Severe COPD could lead to somatic symptoms that are difficult to distinguish from depressive symptoms: eg, change in appetite/weight versus tearfulness/depressed appearance; sleep disturbances versus social withdrawal; fatigue or loss of energy versus brooding/pessimism; and diminished ability to think or concentrate versus lack of reactivity to environmental events. The validity of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5 criteria for depression, in fact, may to a certain degree be questioned, because it is difficult to decide when somatic symptoms are secondary to depression and when they are secondary to COPD.Citation8 Additional variables that have potential to confound the association between COPD and depression regard some common risk factors, including the subject’s demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and marital status), education, body mass index (BMI), alcohol consumption, tobacco use, socioeconomic status (income), respiratory symptoms (dyspnea and difficulty with walking), and comorbid chronic conditions such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, arthritis, hypertension, congestive heart failure, and cancer.Citation9

The nature of the relationship between COPD and depression is not clear. However, it is well documented that depressed patients show a markedly elevated rate of cigarette smoking,Citation10 which is the most important risk factor for COPD. It has been also postulated that (mild) hypoxia – that is also present in COPD patients – can induce central neurobiological changes that predispose to depression and suicide.Citation11 Furthermore, in a study with a large sample, a relevant percentage of COPD patients entering pulmonary rehabilitation experienced clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety and depression.Citation12

However, it could be supposed that both COPD and depression are the clinical manifestations of a common underlying pathophysiologic process. Indeed, data in the literature show that COPD and depression might not be “comorbid” conditions per se, but rather both are pathophysiologically related with a common substrate.Citation13–Citation26

Some authors suggest considering COPD as a “chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome” rather than a respiratory disease associated with extrapulmonary symptoms (including neurocognitive deficits, depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and other non-mental chronic disorders, such as coronary and peripheral artery diseases, anemia, osteoporosis, and rheumatoid arthritis).Citation14

Some characteristics commonly observed in COPD patients, like obesity,Citation27 are indeed associated with inflammation processes related to depression and anxiety,Citation28 suggesting a complex bidirectional association between adiposity and depression.Citation26 In this field, as suggested by some authors, the reduction of adiposity through physical exercise seems related to significant changes in depressive symptoms.Citation29 As a consequence, ATS and ERS guidelines have emphasized the importance of pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with COPD.Citation30

Several authors have indeed shown that there is a strong correlation among physical activity, adiposity, and mental health: several data have suggested that aerobic exercise shows significant effects, comparable to pharmacotherapyCitation31–Citation33 and to psychotherapy,Citation34 on reducing depressive symptomatology.Citation35

Coventry et al specifically demonstrated that structured exercise training significantly reduces both symptoms of depression and anxiety in people with COPD; furthermore, they showed that structured exercise training is more effective than other, complex psychological, behavioral and lifestyle interventions previously thought to improve mental health in people with COPD.Citation36

Pulmonary rehabilitation shows poor effects on lung physiology (eg, ventilation parameters); nevertheless, it improves dyspnea, performance, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and quality of life (QoL).Citation37–Citation42 It also seems to decrease secretory function of adipocytes, resulting in reduction of their volume measured through fat mass.Citation43 In this regard, although BMI is widely used as an indirect parameter to assess adiposity, it has been demonstrated that BMI would have a poor correlation with fat mass, which probably represents a more accurate measure.Citation43

Considering the impact of aerobic exercise on anxious and depressive symptomatology, physical performance, QoL, and adiposity (assessed with BMI and fat mass), the primary aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of aerobic exercise, proposed in the context of pulmonary rehabilitation, through the correlation of psychopathological variables (depressive and anxious symptoms) and physical/pneumological parameters. The secondary endpoint regards the evaluation of potential improvement in QoL and in cognitive performance.

Materials and methods

This prospective cohort study was carried out in pneumology and psychiatry wards in the University Hospital Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele of Catania, Italy from January to June 2012. The study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Policlinico “G. Rodolico” University Hospital, in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association, and written informed consent was obtained by all participants.

Inclusion criteria were diagnosis of COPD and eligibility to perform pulmonary rehabilitation, according to ATS and ERS guidelines.Citation44

Exclusion criteria were indication for restoring treatment of airway patency and current psychopharmacological treatment (including sleeping pills).

Fifty-two consecutive subjects (46 males and six females) were enrolled, with a mean age of 71.5±6.29 years and a mean school education of 8.08±3.21 years.

Enrolled patients started a 6-week rehabilitation protocol, consisting of lower limb/limbs (treadmill and exercise bike) and upper art (arm ergometer Davenbike®) training, as well as calisthenic exercises with increasing intensity from a minimum of 80% to a maximum workload for lower arts in a minimum time.

As proposed by the lung specialists in the pneumology ward of our university hospital, training sessions went on for 2 hours over 5 days a week and were supervised by two physiotherapists and a lung specialist. To exclude potential bias, no change in diet regime was carried out during the full duration of the trial.

Patients were evaluated at first access to pulmonary rehabilitation outpatient wards in order to assess inclusion and exclusion criteria.

For eligible patients, psychometric assessment, completion of the preliminary investigation, and admission in the rehabilitation program were performed. The assessment, measured both at baseline and at the end of the 3-month rehabilitation program, consisted of spirometry with bronchodilator test, walking test (6-minute walk test [6MWT]), BMI, Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnea scale, impedentiometry, motor and metabolic evaluation by SenseWear Armband (for 3 consecutive days), Hopkins Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (subscale HADS-A for anxiety; subscale HADS-D for depression), and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-1 and STAI-2). Cognitive functions were also evaluated using Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices (CPM), Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), Clock Drawing Test (CDT), and Trail Making Test parts A, B, and BA (TMT-A, TMT-B, and TMT-BA).

According to the HAM-D score (cutoff =8), the total sample was divided into two subgroups: depression-positive (D) and depression-negative (ND) subjects.

Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test. Correlations were evaluated using Spearman’s coefficient. Categorical variables were compared by chi-square test. A two-tailed test was used to assess statistical significance; a P-value of <0.05 was considered significant and a P-value of <0.01 was considered highly significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the Intercooled Stata 8 for Windows software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The descriptive analysis of psychometric and pneumological parameters at baseline and at the end of the rehabilitation program (at the end of month 3) are presented in .

Table 1 Descriptive and paired comparison analysis of psychometric and pneumological parameters at baseline and at 3 months in the total sample of patients with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program

Data show that improvement in all pneumological and respiratory parameters was statistically significant, except for Tiffeneau index.

The sample was divided into two subgroups consisting of 38 D and 14 ND subjects according to HAM-D.

The mean and standard deviation of psychometric and pneumological parameters at baseline and month 3 in both patient subgroups are shown in . We did not find a statically significant difference between the two subgroups in age, lung function, and baseline body composition.

Table 2 Descriptive and paired comparison analysis of psychometric and pneumological parameters at baseline and at 3 months in the depression-positive subgroup (n=38) and the depression-negative subgroup (n=14) of patients with COPD in a rehabilitation program

Regarding the mean BMI at baseline, the D subgroup was overweight (24/38 patients, =63%, had a mean BMI 28.37±6.80) and the ND subgroup was normal weight (4/14 patients, =28%, had a mean BMI 24.96±4.1) ( and ), according to WHO criteria,Citation45 even if the absolute difference in BMI between the two subgroups was not statistically significant. Pneumological and psychological parameters overlapped except for HAM-D (P=0.002), HADS-A (P=0.03), SCL-90 (P=0.02), and TMT-A (P=0.02): these differences disappeared at 3 months. At baseline 73% of subjects (38/52) exceeded the cutoff for depression on the HAM-D (D subgroup). At month 3, the rate of D subjects was reduced from 73% to 7.7% (4/52, odds ratio 6.6, P=0.0002). The improvement in almost all other psychological and medical/pneumological parameters was also significant both in the D and ND subgroups at the end of the study.

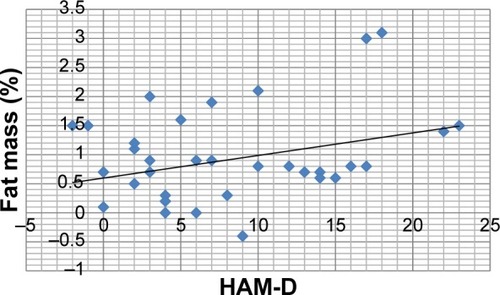

Figure 1 Scatterplot of absolute variations of HAM-D and fat mass from baseline to 3 months in the total sample of patients with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Abbreviation: HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

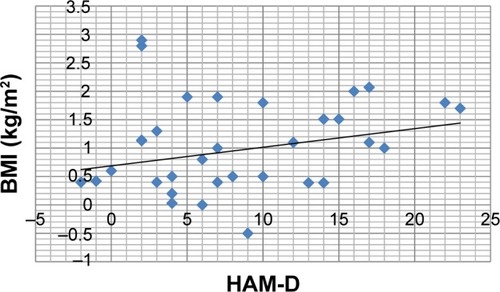

Figure 2 Scatterplot of absolute variations of HAM-D and BMI from baseline to 3 months in the total sample of patients with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

We compared reported differences following the rehabilitation treatment between the D and ND subgroups (); the following parameters showed significant improvements:

HAM-D (D subgroup: 9±2.19, ND subgroup: 3.14±6.20, P=0.02);

HADS-A (D subgroup: 3.84±2.5, ND subgroup: 1:42±1.98, P=0.03); and

SCL-90 (D subgroup: 0.486±0.287, ND subgroup: 0.247±0.177, P=0.05) ().

Table 3 Unpaired comparison analysis of the differences following pulmonary rehabilitative treatment between the D and ND subgroups of patients with COPD

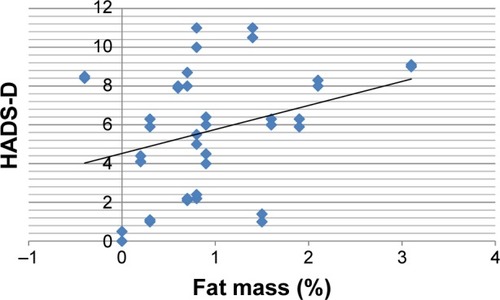

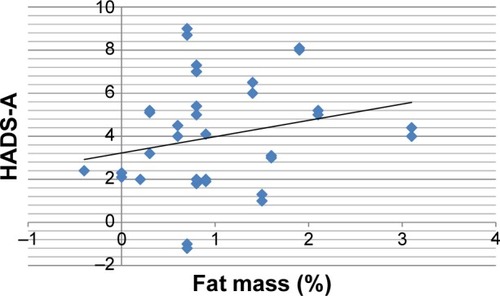

A significant correlation between psychometric (in particular, HADS-A, HADS-D, STAI-2, SCL-90, TMT-B, TMT-BA, and CPM) and internistic parameters was found, especially with fat mass and BMI in the total population: the reduction in fat mass and BMI was related to decreased anxiety and depression and improved QoL and cognitive performance ( and ; –).

Table 4 Correlation analysis of the difference in psychometric and pneumological parameters, observed at baseline and at 3 months in the subgroup (n=38) of depression-positive subjects with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program

Table 5 Correlation analysis of the difference in psychometric and pneumological parameters, observed at baseline and at 3 months in the subgroup (n=14) of depression-negative subjects with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program

Figure 3 Scatterplot of absolute variations of fat mass and HADS-D from baseline to 3 months in the depression-positive subgroup of patients with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Abbreviation: HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, depression subscale.

Figure 4 Scatterplot of absolute variations of fat mass and HADS-A from baseline to 3 months in the depression-positive subgroup of patients with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

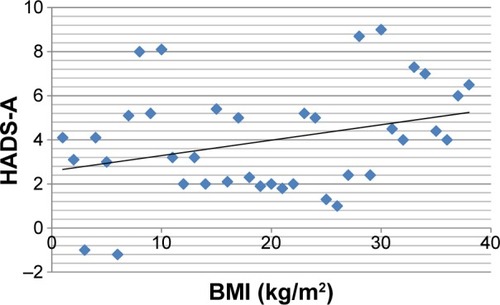

Abbreviation: HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, anxiety subscale.

Figure 5 Scatterplot of absolute variations of BMI and HADS-A from baseline to 3 months in the depression-positive subgroup of patients with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, anxiety subscale.

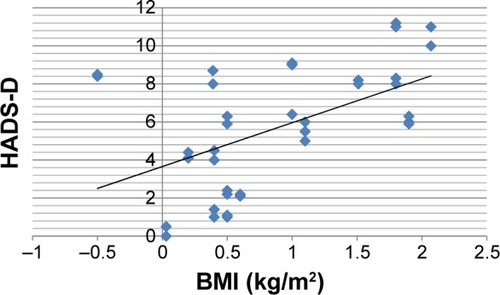

Figure 6 Scatterplot of absolute variations of BMI and HADS-D from baseline to 3 months in the depression-positive subgroup of patients with COPD in a pulmonary rehabilitation program.

At baseline in group D, a significant correlation was present between BMI and the following psychometric variables: HADS-A (r=0.47, P=0.04); HADS-D (r=0.5, P=0.02); SCL-90 (r=0.56, P=0.01); STAI-2 (r=0.51, P=0.02); TMT-A (r=0.52, P=0.02); TMT-B (r=0.44, P=0.05); RAVLT (r=−0.49, P=0.03); and CPM (r=−0.63, P=0.003) ( and ; and ). These correlations were not statistically significant in subgroup ND.

A significant correlation between BMI and fat mass was present at baseline in subgroup D (r=0.8667, P=0.0000) but not in subgroup ND (r=0.3929, P=0.3833).

In subgroup D, the reduction in BMI was significantly related with fat mass (r=0.6072, P=0.005), but the same could not be affirmed for patients of the ND subgroup ( and ).

Discussion

In agreement with other findings,Citation5,Citation6 we found a high prevalence (73%) of patients with depressive symptoms at baseline in our COPD subjects that showed a significant decrease at the end of the rehabilitation program (7.7%). Previous reviews on pulmonary rehabilitation have indicated that 4-week programs can improve fatigue and emotional function, but these reviews included trials that did not specifically address effects on anxiety and depression,Citation36,Citation46 while in our results, the mean HAM-D scores (used in our research to divide the whole population into the two subgroups and for the evaluation of the changes of depressive symptoms) decreased significantly both in the total sample and in the D and ND subgroups.

Another study examined the relationship between depression and aerobic exercise in generic chronic illness patients;Citation47 some others found a correlation between depression and/or anxiety and aerobic exercise in COPD patients undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation, but they did not investigate variables such as BMI or obesity.Citation36,Citation48–Citation51

Moreover, in our trial, all other assessed psychiatric (depression, anxiety, and cognitive function) and medical/pneumological parameters demonstrated a significant improvement after the rehabilitation program.

The evaluation of cognitive performances, improved at 3 months, showed some peculiarities: the improvement in visual-spatial attention (TMT-A), although significant, was modest if compared with the TMT-B parameter, which assesses attention shifting ability and visual-spatial attention, as summarized by TMT-BA that represents the difference between the times of part B and those of part A in executive functioning ().

Memory, assessed by RAVLT, was significantly enhanced at 3 months both in immediate and in deferred recall (), such as praxic skills, mental representation, and planning (assessed by CDT) and deduction skills (evaluated through CPM) ().

We highlight the interesting correlations among STAI-1, MRC, and BODE (BMI, obstruction, dyspnea, exercise capacity) index: decrease in anxiety correlated with the improvement of dyspnea (MRC) and BODE index in the absence of correlation with objective indices such as forced expiratory volume in the 1st second, BMI, and 6MWT; this fact could be explained by the tendency of anxious depressed patients to amplify dyspnea.Citation52

The improvement in psychological parameters (anxiety and depressive symptoms, QoL, and cognitive performances) was related to a general decrease of fat mass and BMI in the total sample ( and ). In subgroup D, this correlation was particularly evident between BMI and the following psychometric variables: HADS-A, HADS-D, SCL-90, STAI-2, TMT-A, TMT-B, RAVLT, and CPM (). Despite the general decrease of fat mass and BMI in the total sample, it was not statistically significant in subgroup ND, for which, unlike subgroup D (), there was no correlation between BMI and fat mass, both at baseline and after the rehabilitation program. In this sense, BMI alone could be insufficient to explain the correlation with psycho-pathological parameters.

The different results observed between the two subgroups could be explained by the fact that D-subgroup patients presented a baseline condition of “overweight” and a higher fat mass percentage, not recorded in the ND subgroup, which was mainly composed of persons of normal weight. The only factor that indeed correlated with the majority of psychometric parameters was BMI, but only in subgroup D, where we recorded a correlation between BMI and fat mass.

In spite of the interesting findings, at least three limitations must be considered. First, metabolic and neurobiological analysis (eg, inflammatory and oxidative markers) could explain the link between anxiety and depressive symptoms and internistic medical disorders, such as COPD, in order to define a new meaning and management of them, but in this study was not performed. Second, the lack of muscle mass evaluation could influence depressive and anxious symptoms.Citation53 Third, our sample size was small. So further studies are needed to evaluate the link between psychopathological symptoms and COPD in terms of inflammatory and oxidative markers with specific measures of them and the impact of muscle wasting on depression and anxiety in this specific population and, at the end, to augment the power of statistical analysis.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that it might be useful, in the context of multiple chronic diseases, to start a specific rehabilitation program (eg, of aerobic exercise) in order to establish a more appropriate and integrated therapeutic approach where there is suspicion, that needs to be confirmed, that a condition of increased adiposity could influence the genesis and evolution of psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Filippo Palermo (University of Catania) for his support in statistical analysis.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work and have received no payment in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- MurrayCJLopezADAlternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease StudyLancet1997349149815049167458

- LopezADMurrayCCThe global burden of disease, 1990–2020Nat Med19984124112439809543

- CelliBRPauwelsRSniderGLDefinition, diagnosis and stagingStandards for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients with COPDNew YorkAmerican Thoracic SocietyLausanneEuropean Respiratory Society2004813

- JansonCBjörnssonEHettaJBomanGAnxiety and depression in relation to respiratory symptoms and asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med19941499309348143058

- Di MarcoFVergaMReggenteMAnxiety and depression in COPD patients: the roles of gender and disease severityRespir Med2006100101767177416531031

- van ManenJGBindelsPJDekkerFWIJzermansCJvan der ZeeJSSchadéERisk of depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinantsThorax20025741241611978917

- OrmelJKempenGIDeegDJBrilmanEIvan SonderenERelyveldJFunctioning, well-being, and health perception in late middle-aged and older people: comparing the effects of depressive symptoms and chronic medical conditionsJ Am Geriatr Soc19984639489434664

- StageKBMiddelboeTStageTBSørensenCHDepression in COPD – management and quality of life considerationsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20061331532018046868

- SchaneREWalterLCDinnoACovinskyKEWoodruffPGPrevalence and risk factors for depressive symptoms in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Gen Intern Med200823111757176218690488

- BodenJMFergussonDMHorwoodLJCigarette smoking and depression: tests of causal linkages using a longitudinal birth cohortBr J Psychiatry201019644044620513853

- DelMastroKHellemTLKimNKondoDSungYHRenshawPFIncidence of major depressive episode correlates with elevation of substrate region of residenceJ Affect Disord201112937637921074272

- JanssenDJSpruitMALeueCCiro networkSymptoms of anxiety and depression in COPD patients entering pulmonary rehabilitationChron Respir Dis20107314715720688892

- KocabasATezcagirirGSeydaogluGOzyilmazEThe relationship between comorbidities and systemic inflammation in patients with COPDEur Respir J201138Suppl 554057

- FabbriLMRabeKFFrom COPD to chronic systemic inflammatory syndrome?Lancet200737079779917765529

- JefferyPKLaitinenAVengePBiopsy markers of airway inflammation and remodellingRespir Med200094Suppl FS9S1511059962

- YanbaevaDGDentenerMASpruitMAIL6 and CRP haplotypes are associated with COPD risk and systemic inflammation: a case-control studyBMC Med Genet2009102319272152

- YendeSWatererGWTolleyEAInflammatory markers are associated with ventilatory limitation and muscle dysfunction in obstructive lung disease in well functioning elderly subjectsThorax2006611101616284220

- GanWQManSFSenthilselvanASinDDAssociation between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysisThorax200459757458015223864

- HaddadFZaldivarFCooperDMAdamsGRIL-6-induced skeletal muscle atrophyJ Appl Physiol (1985)200598391191715542570

- LangenRCScholsAMKeldersMCVan Der VeldenJLWoutersEFJanssen-HeiningerYMTumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits myogenesis through redox-dependent and -independent pathwaysAm J Physiol Cell Physiol20022833C714C72112176728

- PotashkinJAMeredithGEThe role of oxidative stress in the dysregulation of gene expression and protein metabolism in neurodegenerative diseaseAntioxid Redox Signal2006814415116487048

- DantzerRCytokine, sickness behavior, and depressionImmunol Allergy Clin North Am20092924726419389580

- HohagenFTimmerJWeyerbrockACytokine production during sleep and wakefulness and its relationship to cortisol in healthy humansNeuropsychobiology1993281–29168255417

- LehtoSMHuotariANiskanenLSerum IL-7 and G-CSF in major depressive disorderProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry201034684685120382196

- del ReyAFurukawaHMonge-ArditiGKabierschAVoigtKHBesedovskyHOAlterations in the pituitary-adrenal axis of adult mice following neonatal exposure to interleukin-1Brain Behav Immun19961032352488954596

- SheltonRCMillerAHEating ourselves to death (and despair): the contribution of adiposity and inflammation to depressionProg Neurobiol20109127529920417247

- FranssenFMO’DonnellDEGoossensGHBlaakEEScholsAMObesity and the lung: 5. Obesity and COPDThorax2008631110111719020276

- CapuronLMillerAHImmune system to brain signaling: neuro-psychopharmacological implicationsPharmacol Ther201113022623821334376

- EyreHBauneBTNeuroimmunological effects of physical exercise in depressionBrain Behav Immun20122625126621986304

- NiciLDonnerCWoutersEATS/ERS Pulmonary Rehabilitation Writing CommitteeAmerican Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement on pulmonary rehabilitationAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006173121390141316760357

- BabyakMBlumenthalJAHermanSExercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 monthsPsychosom Med200062563363811020092

- MooreKABlumenthalJAExercise training as an alternative treatment for depression among older adultsAltern Ther Health Med1998448569439020

- RoseCWallaceLDicksonRThe most effective psychologically-based treatments to reduce anxiety and panic in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic reviewPatient Educ Couns200247431131812135822

- KleinMHGreistJHGurmanASA comparative outcome study of group psychotherapy vs exercise treatments for depressionInt J Ment Health1984198513148176

- MartinsenEWHoffartASolbergOComparing aerobic with nonaerobic forms of exercise in the treatment of clinical depression: a randomized trialCompr Psychiatry1989303243312667882

- CoventryPABowerPKeyworthCThe effect of complex interventions on depression and anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysisPLoS One201384e6053223585837

- ZuWallackRHashimAMcCuskerCNormandinEBenoit-ConnorsMLLahiriBThe trajectory of change over multiple outcome areas during comprehensive outpatient pulmonary rehabilitationChron Respir Dis200631111816509173

- NiciLZuWallackRWoutersEDonnerCFOn pulmonary rehabilitation and the flight of the bumblebee: the ATS/ERS Statement on Pulmonary RehabilitationEur Respir J200628346146216946088

- RiesALKaplanRMLimbergTMPrewittLMEffects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiologic and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med1995122118238327741366

- GriffithsTLBurrMLCampbellIAResults at 1 year of outpatient multidisciplinary pulmonary rehabilitation: a randomised controlled trialLancet2000355920136236810665556

- LacasseYWongEGuyattGHKingDCookDJGoldsteinRSMeta-analysis of respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLancet19963489035111511198888163

- DeromEMarchandETroostersTPulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Readapt Med Phys20075061562617559963

- WangJThorntonJCRussellMBurasteroSHeymsfieldSPiersonRNJrAsians have lower body mass index (BMI) but higher percent body fat than do whites: comparisons of anthropometric measurementsAm J Clin Nutr199460123288017333

- WoutersEFMZuWallackRLareauSCManagement of stable COPD: pulmonary rehabilitationStandards for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients with COPDNew YorkAmerican Thoracic SocietyLausanneEuropean Respiratory Society2004100112

- World Health OrganizationObesity and Overweight Fact sheet no 311GenevaWorld Health Organization2015 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/Accessed November 20, 2015

- LacasseYGoldsteinRLassersonTJMartinSPulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20064CD00379317054186

- HerringMPPuetzTWO’ConnorPJDishmanRKEffect of exercise training on depressive symptoms among patients with a chronic illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsArch Intern Med2012172210111122271118

- Paz-DíazHMontes de OcaMLópezJMCelliBRPulmonary rehabilitation improves depression, anxiety, dyspnea and health status in patients with COPDAm J Phys Med Rehabil2007861303617304686

- GarutiGCilioneCDell’OrsoDImpact of comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation on anxiety and depression in hospitalized COPD patientsMonaldi Arch Chest Dis2003591566114533284

- TselebisABratisDPachiAA pulmonary rehabilitation program reduces levels of anxiety and depression in COPD patientsMultidiscip Respir Med2013814123931626

- BhandariNJJainTMaroldaCZuWallackRLComprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation results in clinically meaningful improvements in anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev201333212312723399845

- RamasamyRHildebrandtTO’HeaEPsychological and social factors that correlate with dyspnea in heart failurePsychosomatics200647543043416959932

- VanfleterenLESpruitMAGroenenMClusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187772873523392440