Abstract

Background

Potential associations between oral health and respiratory disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), have been suggested in several studies. Among the indicators reflecting oral health, the number of natural teeth is an integrated and simple index to assess in the clinic. In this study, we examined the relationship between the number of natural teeth and airflow obstruction, which is a central feature of COPD.

Methods

A total of 3,089 participants over 40 years, who underwent reliable spirometry and oral health assessments were selected from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2012, a cross-sectional and nationally representative survey. Spirometry results were classified as normal, restrictive, or obstructive pattern. Total number and pairs of natural teeth were counted after excluding third molars.

Results

After adjusting for other variables, such as age, body mass index, socioeconomic factors, and oral health factors, the group with airflow obstruction showed significantly fewer natural teeth than the other groups in males (P=0.014 and 0.008 for total number and total pairs of natural teeth, respectively). Compared with participants with full dentition, the adjusted odds ratio for airflow obstruction in males with fewer than 20 natural teeth was 4.18 (95% confidence interval: 2.06–8.49) and with fewer than 10 pairs of natural teeth was 4.74 (95% confidence interval: 2.34–9.62). However, there was no significant association between the total number or pairs of natural teeth and airflow obstruction after adjustment in females.

Conclusions

Loss of natural teeth was significantly associated with the presence of airflow obstruction in males. Our finding suggests that the number of natural teeth could be one of the available indices for obstructive lung diseases, including COPD.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a lung disease characterized by airflow limitations that are not fully reversible, is a major cause of chronic morbidity and mortality worldwide.Citation1–Citation3 The Global Burden of Disease study predicted that COPD is predicted to rise from the sixth most common cause of mortality worldwide, to the third most common cause of mortality in 2020.Citation4 Additionally, with the aging of the population, the burden of COPD is increasing continuously.Citation5–Citation7 However, recent data likely underestimate the total burden of COPD because the disease is usually not diagnosed until it is clinically apparent and already moderately advanced.Citation8

Although COPD is primarily a pulmonary disease associated with an abnormal inflammatory response in the lungs, COPD is also associated with a certain degree of systemic inflammation, which has been correlated with adverse clinical effects.Citation9–Citation11 Several studies have reported potential associations between oral health and respiratory diseases, including COPD.Citation12–Citation14 Scannapieco and MylotteCitation15 suggested that periodontal disease might change oral microbiological conditions and permit mucosal colonization and infection by respiratory pathogens.Citation15 Additionally, oral health is likely to interact with other cofactors (eg, smoking, environmental pollutants, infection, allergy, genetic factors) that are also important in COPD patients.Citation16 Among indicators of oral health, the number of natural teeth can be rapidly and easily determined in the clinic. Öztekin et alCitation17 reported that the number of teeth was significantly lower in COPD patients. Barros et alCitation11 reported that edentulous COPD patients were at greater risk of having a COPD-related event (hospitalization and death).

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between the number of natural teeth and airflow obstruction, which is a central feature of COPD, by analyzing data from the Korean population.

Materials and methods

Study population

Data were collected from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), which was performed by the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare) in 2012.Citation18 KNHANES has been conducted regularly since 1998 to monitor the general health and nutritional status of the civilian, noninstitutionalized South Korean population. Participants were selected using proportional allocation-systemic sampling with multistage stratification to produce a nationally representative sample of the resident, civilian Korean population. Prior to the national survey, all participants provided written informed consent. Moreover, all databases were anonymized. KNHANES comprised three sections: a health interview survey, a health examination, and a nutrition survey.Citation18 Additional details about the KNHANES have been provided elsewhere.Citation18 Among participants in the survey in 2012, this current study analyzed participants over 40 years who underwent reliable spirometry and oral health assessments (n=3,089; 1,291 males and 1,798 females). The age range was 40–88 years for males and 40–87 years for females. Participants with asthma were excluded according to medical history. This current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St Mary’s Hospital. The Institutional Review Board of Seoul St Mary’s Hospital did not require patient consent for this present study because all participants gave their consent for the KNHANES before the registration, and the KNHANES data is open to the public after being anonymized.

Measurements and variables

Height, weight, and waist circumference (WC) were measured with standard procedures. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. WC was measured at the midpoint of the lower margin of the 12th rib and the iliac crest in the midaxillary line at the end of expiration. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

All participants were asked about their demographic characteristics, socioeconomic characteristics, and medical history. Trained interviewers performed the interviews using structured questionnaires. Smoking status was categorized as ever smokers and nonsmokers. Subjects were considered as ever smokers if they had smoked >100 cigarettes in their lifetime. The amount of alcohol consumed (in g/day) was calculated using the average number of alcoholic beverages ingested and frequency of drinking. Subjects who drank more than 30 g/day were deemed heavy drinkers. Monthly income was standardized according to the number of family members (monthly income/√number of family members) and was divided into four quartile groups: lowest, lower middle, higher middle, and highest (Table S1). Low income corresponded to the lowest quartile of household income. Education level was classified as high, if the subjects finished high school education or more (higher than 12th grade). Geographic regions were classified as rural (Gangwon, Chungbuk, Chungnam, Jeonbuk, Jeonnam, Gyeongbuk, Gyeongnam, and Jeju) or urban (Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Daejeon, Gwangju, Incheon, Ulsan, and Gyeonggi) areas. Marriage was checked from the presence of a spouse. Regular exercise was defined as strenuous physical activity performed for at least 20 minutes at a time at least three times per week.

The nutrition surveys included questions about the participant’s eating pattern, use of dietary supplements, knowledge of nutrition, and food intake using the 24 hours recall method. The total energy intake and the percentage of energy from each nutrient (fat, carbohydrate, and protein) were then calculated.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as a fasting glucose level ≥126 mg/dL, the current use of antidiabetic medications, or a self-reported physician diagnosis of DM. Metabolic syndrome was defined using the diagnostic guidelines from the American Heart Association and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.Citation19 Vitamin D is well known for its crucial role in bone homeostasis. Vitamin D showed significant association with pulmonary function, periodontitis, and tooth loss as seen from other studies.Citation20,Citation21 Vitamin D level was measured with a 1470 Wizard γ-counter (Perkin-Elmer, Turku, Finland) using a radioimmunoassay.

Spirometry and definition of airflow obstruction

Licensed trained technicians measured the forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and the FEV1/FVC ratio using a dry rolling seal spirometer (model 2130; SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). A quality-control program was performed; the spirometer was calibrated every morning before performing spirometry (and recalibrated every time the room temperature changed by 3°C), and the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society criteria of acceptability and repeatability were followed by the examiners on site. All of the spirometry values were described as prebronchodilator results. Normal predicted values were derived from large population studies of healthy subjects. Variables used to predict normal values included age, sex, height, and ethnicity.Citation22 Spirometry results were classified as normal, restrictive, and obstructive pattern. Subjects with FEV1/FVC ≥70% and FVC ≥80% of the normal predicted value were considered normal.Citation23,Citation24 When FEV1/FVC ≥70% and FVC was under 80% of the normal predicted value, the subjects were classified as restrictive pattern. Obstructive pattern, which we considered to have airflow obstruction in this study, was defined with FEV1/FVC <70%. The severity of airflow obstruction was based on the percentage of normal predicted prebronchodilator FEV1.

Number and pairs of natural teeth

The KNHANES 2012 oral health data recorded the status for each of the 32 teeth. In this study, total number and pairs of natural teeth were counted after excluding third molars. Based on this information, we categorized the subjects into three groups according to total numbers of natural teeth: full dentition (28 teeth), 20–27 teeth, and fewer than 20 teeth. We also classified the subjects into one of three groups according to pairs of natural teeth.

Other oral health assessment

The World Health Organization community periodontal index (CPI) was used to assess periodontitis and when CPI ≥code 3, we deemed this to be periodontitis.Citation25,Citation26 Code 3 indicates that at least one site had a >3.5 mm pocket in the index teeth, which are 2, 3, 8, 14, 15, 18, 19, 24, 30, and 31, according to the Universal Numbering System, which has been adopted by the American Dental Association. A CPI probe, which is appropriate for the World Health Organization guidelines, was used. We also checked the number of tooth brushings and the use of secondary oral products for assessing oral health behavior. Number of tooth brushings was categorized as once, twice, and three or more times per day. Secondary oral products included mouthwash, dental floss, water flosser, an interdental brush, and an electric toothbrush.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard error for continuous variables or as proportions (standard error) for categorical variables. Logarithmic transformation was used to analyze variables with skewed distributions. Statistical analyses were performed with the SAS survey procedure (ver 9.3; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) to reflect the complex sampling design and sampling weights of KNHANES and to provide nationally representative prevalence estimates. The χ2 test was used with categorical variables and a one-way analysis of variance with continuous variables. We used analysis of covariance to compare the number and pairs of the natural teeth according to lung function after adjusting for potential confounders. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate the association of airflow obstruction and the number of natural teeth. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated after adjustment for potential confounders. In the multivariate analyses for the number and pairs of natural teeth, we first adjusted for age (model 1) and then adjusted for the variables in model 1 plus smoking, drinking, exercise, income, education, and BMI (model 2). Finally, model 3 adjusted for the variables in model 2 plus periodontitis, number of tooth brushings, and the use of secondary oral products. P-values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study population are shown in . All subjects were categorized into three groups (normal, restrictive, and obstructive) according to their pulmonary function test. Among the total population, 12.9% had obstructive lung function, 10.0% had restrictive lung function, and 77.2% had normal lung function. Difference between males and females was 20.1% versus 6.0%, 8.9% versus 11.0%, and 71.0% versus 83.0% for obstructive, restrictive, and normal lung function, respectively. There were significant differences among the three groups in age (P<0.001, both), height (P<0.001 and P=0.017, respectively), weight (P<0.001, both), BMI (P<0.001, both), and WC (P<0.001 and P=0.002, respectively) in males and females. The obstructive group was older and had lower weight and BMI. The restrictive group showed higher weight, BMI, and WC. The normal group was taller than the other groups.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the participants

In socioeconomic characteristics, there were significant differences in income (P<0.001, both) and education (P<0.001, both) in males and females. The obstructive group showed lower income and education than the other groups. In males, the obstructive group showed significantly more smokers (P=0.040), less exercise (P=0.042), and total energy (P=0.041). There were more unmarried females in the obstructive group (P<0.001). Although the amount of total energy was smaller in the obstructive group in females, the difference was of borderline significance (P=0.054).

DM (P=0.003 and P=0.002) and metabolic syndrome (P<0.001, both) were significantly more frequent in the restrictive group (males and females). Vitamin D levels were significantly higher in the obstructive group in males (P=0.005).

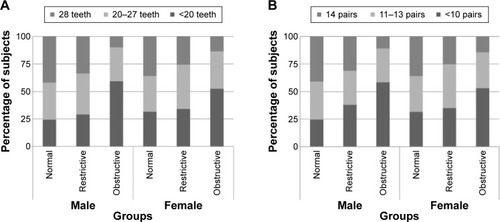

In terms of oral health, number of natural teeth was significantly lower in the obstructive group in males and females (P<0.001, both). Periodontitis index, number of tooth brushings, and use of secondary oral products showed no significant difference in the three groups. In both males and females, the proportion of participants with full dentition and all pairs of natural teeth tended to decrease in the order normal, restrictive, and obstructive group (). The obstructive group showed considerable decreases versus the other groups. The proportion of individuals who had fewer than 20 natural teeth or fewer than 10 pairs of natural teeth showed a reverse pattern, in both males and females. Number and pairs of natural teeth showed the same pattern and distribution. However, males showed greater changes in the trend and distribution than females.

Figure 1 Distribution of number of natural teeth (A) and pairs of natural teeth (B) with lung function.

We adjusted for variables that might influence the association between total number of natural teeth and lung function (). After adjusting for age, BMI, socioeconomic status (smoking, drinking, exercise, income, education), and oral health indexes (periodontitis, number of tooth brushings, and use of secondary oral products), the obstructive group showed significantly fewer natural teeth than the other groups in males (P=0.014 and P=0.008 for total number and total pairs of natural teeth, respectively). There was no significant difference after adjustment in females in the total number or pairs of natural teeth.

Table 2 Multivariate adjusted number and pairs of natural teeth and lung function

The subjects were divided into three groups according to the total number (<20, 20–27, 28) and pairs (<10, 10–13, 14) of natural teeth (). After adjusting for age, BMI, socioeconomic status, and oral health indexes, ORs for airflow obstruction were 4.18 (95% CI =2.06–8.49) and 3.21 (95% CI =1.85–5.58) in the groups with total numbers of teeth below 20 and 20–27, respectively. The adjusted OR for airflow obstruction of total pairs of natural teeth was 4.74 (95% CI =2.34–9.62) and 3.08 (95% CI =1.79–5.32) in the groups with total pairs of teeth below 10 and 10–13, respectively. There was no significant relationship between the number or pairs of natural teeth and airflow obstruction in females.

Table 3 Risk of airflow obstruction according to the number or pairs of natural teeth

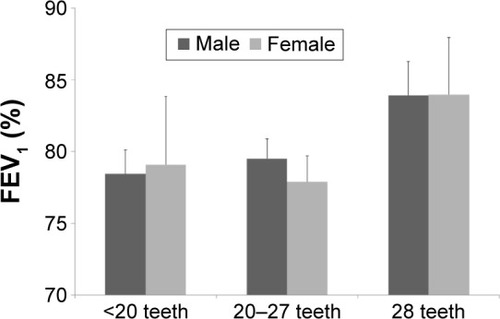

shows the trend of FEV1 with subgroups of the number of natural teeth in patients with airflow obstruction. In both sexes, FEV1 showed a decreasing trend in the groups with 20–27 teeth and <20 teeth compared with the 28-teeth group after adjustment for confounding factors (age, smoking, drinking, exercise, income, education, and BMI).

Figure 2 FEV1 with subgroups of the number of natural teeth in patients with airflow obstruction.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

Although our study is a cross-sectional study using the results of prebronchodilator spirometry, we detected a statistically significant association between the number or pairs of natural teeth and airflow obstruction in males, even after adjusting for other variables such as age, BMI, socioeconomic factors (smoking, drinking, exercise, income, education), and oral health factors (periodontitis, number of tooth brushings, use of secondary oral products). The adjusted OR for airflow obstruction in males with fewer than 20 natural teeth was 4.18 (2.06–8.49) and that in males with fewer than 10 pairs of natural teeth was 4.74 (2.34–9.62). However, there was no significant association between the number or pairs of natural teeth and airflow obstruction in females. Within patients with airflow obstruction, percentage of normal predicted FEV1 tended to decrease with tooth loss. However, there was no statistically significant relationship between the number of natural teeth and percentage of normal predicted FEV1.

Previous studies have suggested an association between airflow obstruction, which is a central feature of COPD, and poor oral health.Citation12,Citation16,Citation27–Citation30 Scannapieco et alCitation12 investigated the association between oral conditions and respiratory disease using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I.Citation12 Subjects with maximum oral hygiene index values were 4.5-fold more likely to have a chronic respiratory disease than those with an oral hygiene index of 0 in their study. Hayes et alCitation28 investigated the association between COPD and periodontal disease, assessed by radiographic alveolar bone loss. They showed that increased alveolar bone loss was associated with an increased risk of COPD. A case–control study with 581 COPD cases and 438 non-COPD controls was performed by Si et alCitation27 in a Chinese population. The results showed a strong association between periodontitis and COPD, and plaque index was a major periodontal factor for predicting COPD (OR =9.01, 95% CI =3.98–20.4).

Although oral conditions likely work in concert with other factors and the underlying biological mechanisms still remain obscure,Citation16 several mechanisms were suggested in these various studies to explain the association of COPD with poor oral health. Aspiration of oral pathogens into the lower respiratory tract was one of these hypotheses.Citation31 Periodontal disease-associated enzymes in saliva may also change respiratory environmental conditions, permitting mucosal colonization and infection by respiratory pathogens.Citation15,Citation28,Citation31 In addition, the association between poor oral health and respiratory disease was suggested to be mediated through systemic inflammatory responses.Citation9,Citation32 Inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6 or IL-8, from periodontal tissues may alter the respiratory epithelium to promote infection by respiratory pathogens.Citation16 From other studies, tooth loss or less frequently brushing teeth was associated with an increased serum level of C-reactive protein.Citation33–Citation35 Levels of inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein and IL-6 also have been reported to be elevated in COPD.Citation11

In this study, we used the number of natural teeth as a measure of oral health. Rather than actually investigating oral hygiene or the presence of periodontitis, the number of natural teeth is a rapid and easy index for both clinicians and patients. Changes in oral health status due to caries and periodontitis lead to a reduced number of teeth.Citation36 Additionally, Kressin et alCitation37 showed that many oral health behaviors, including brushing, flossing, and prophylactic dental visits, can help retain a greater number of natural teeth.Citation37 In our al products. We believe that the cumulative effects of diverse oral health factors are reflected in the number of teeth. We used pairs of natural teeth as a marker to reflect dental function, such as biting and chewing. In several other studies, functional units, defined as any opposing natural or prosthetic tooth pair, were used to account for the functional arrangement of the teeth.Citation38–Citation40 From our results, both number and pairs of natural teeth showed an almost identical correlation with airflow obstruction. Males who had low numbers or pairs of teeth showed a stronger relationship with airflow obstruction.

In both sexes, patients with airflow obstruction tended to have the following characteristics: older in age, lower BMI, lower income, and less education. Subjects with restrictive lung patterns showed higher BMI, WC, and presence of DM and metabolic syndrome in both males and females. However, only male subjects with airflow obstruction comprised a significantly greater number of smokers, partook in less exercise, and had a lower total energy intake. This difference may be because Korean females in the general population traditionally have a low smoking rate, exercise, and total energy intake. Contrary to our expectations, levels of vitamin D were significantly higher in males with airflow obstruction. Several studies have reported a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in COPD patients.Citation41–Citation44 This may be explained by the nature of the study population. All study groups showed vitamin D deficiency (<20 ng/mL) regardless of lung function, and the group with airflow obstruction consisted mostly of mild cases.

After adjustments, the number or pairs of teeth were significantly related to airflow obstruction only in males. In females, other confounding factors, such as hormonal effects and the frequency of dental checkups, which were not considered in this study, may have influenced the results. Additionally, the relationship between the number of natural teeth and airflow obstruction in females according to the severity of airflow obstruction should be compared in further studies.

Our study had several limitations. First, postbronchodilator spirometry was not performed in KNHANES. Using the results of prebronchodilator spirometry for diagnosing COPD may overestimate the number of COPD patients. Therefore, we defined the obstructive pattern of spirometry as “airflow obstruction” instead of COPD. Second, the study was of a cross-sectional design and so no cause–effect relationship could be determined. Third, this study involved healthy patients with mild airflow obstruction rather than those with severe airflow obstruction. KNHANES data were obtained from subjects participating in a nationwide survey; individuals who were admitted to hospitals or nursing homes were not included. Within these limitations, the KNHANES data represent the public health of the total population of Korea and is of considerable value in many respects.Citation45

Despite these limitations, there are several strengths in our study. First, the number of teeth and oral condition was objectively assessed by dentist with same criteria. In addition, several physical examinations and important confounding variables were also precisely recorded by trained examiners. Second, our study included a large number of participants who represent the Korean population. Third, we used the number of natural teeth, which is a convenient index and reflects the cumulative effects of oral health.

Conclusion

Loss of natural teeth was significantly associated with the presence of airflow obstruction in Korean males. Based on our results, the number of natural teeth could be one of the available indices for obstructive lung diseases, including COPD. Further investigations are needed to clarify the relationship and mechanism between the oral health and obstructive lung diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a research grant from the Institute of Clinical Medicine Research, Yeouido St Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea.

Supplementary material

Table S1 Standard of monthly household incomeTable Footnote* (US dollar)

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- VestboJHurdSSAgustiAGGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187434736522878278

- MaySMLiJTBurden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: healthcare costs and beyondAllergy Asthma Proc201536141025562549

- PauwelsRARabeKFBurden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Lancet2004364943461362015313363

- MurrayCJLopezADAlternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease StudyLancet19973499064149815049167458

- TsaiTYLivnehHLuMCTsaiPYChenPCSungFCIncreased risk and related factors of depression among patients with COPD: a population-based cohort studyBMC Public Health20131397624138872

- SullivanSDRamseySDLeeTAThe economic burden of COPDChest20001172 Suppl5s9s10673466

- ChapmanKRManninoDMSorianoJBEpidemiology and costs of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseEur Respir J200627118820716387952

- CelliBRMacNeeWStandards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paperEur Respir J200423693294615219010

- BarnesPJCelliBRSystemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPDEur Respir J20093351165118519407051

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- BarrosSPSurukiRLoewyZGBeckJDOffenbacherSA cohort study of the impact of tooth loss and periodontal disease on respiratory events among COPD subjects: modulatory role of systemic biomarkers of inflammationPLoS One201388e6859223950871

- ScannapiecoFAPapandonatosGDDunfordRGAssociations between oral conditions and respiratory disease in a national sample survey populationAnn Periodontol1998312512569722708

- AzarpazhoohALeakeJLSystematic review of the association between respiratory diseases and oral healthJ Periodontol20067791465148216945022

- ZhouXWangZSongYZhangJWangCPeriodontal health and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med20111051677320630736

- ScannapiecoFAMylotteJMRelationships between periodontal disease and bacterial pneumoniaJ Periodontol19966710 Suppl111411228910830

- ScannapiecoFAHoAWPotential associations between chronic respiratory disease and periodontal disease: analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey IIIJ Periodontol2001721505611210073

- ÖztekinGBaserUKucukcoskunMThe association between periodontal disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case control studyCOPD201411442443024378084

- Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention2015Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), 2012 Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/index.doAccessed March 27, 2015

- GrundySMCleemanJIDanielsSRDiagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific StatementCirculation2005112172735275216157765

- LehouckABoonenSDecramerMJanssensWCOPD, bone metabolism, and osteoporosisChest2011139364865721362651

- JimenezMGiovannucciEKrall KayeEJoshipuraKJDietrichTPredicted vitamin D status and incidence of tooth loss and periodontitisPublic Health Nutr201417484485223469936

- RanuHWildeMMaddenBPulmonary function testsUlster Med J2011802849022347750

- ParkHJLeemAYLeeSHComorbidities in obstructive lung disease in Korea: data from the fourth and fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101571158226300636

- ChungJHHwangHJHanCHSonBSKim doHParkMSAssociation between sarcopenia and metabolic syndrome in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) from 2008 to 2011COPD2015121828924914701

- LeeJBYiHYBaeKHThe association between periodontitis and dyslipidemia based on the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyJ Clin Periodontol201340543744223480442

- KingmanASusinCAlbandarJMEffect of partial recording protocols on severity estimates of periodontal diseaseJ Clin Periodontol200835865966718513337

- SiYFanHSongYZhouXZhangJWangZAssociation between periodontitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a Chinese populationJ Periodontol201283101288129622248220

- HayesCSparrowDCohenMVokonasPSGarciaRIThe association between alveolar bone loss and pulmonary function: the VA Dental Longitudinal StudyAnn Periodontol1998312572619722709

- DeoVBhongadeMLAnsariSChavanRSPeriodontitis as a potential risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective studyIndian J Dent Res200920446647020139573

- LeuckfeldIObregon-WhittleMVLundMBGeiranOBjortuftOOlsenISevere chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: association with marginal bone loss in periodontitisRespir Med2008102448849418191392

- VadirajSNayakRChoudharyGKKudyarNSpoorthiBRPeriodontal pathogens and respiratory diseases-evaluating their potential association: a clinical and microbiological studyJ Contemp Dent Pract201314461061524309337

- MontebugnoliLServidioDMiatonRAPratiCTricociPMelloniCPoor oral health is associated with coronary heart disease and elevated systemic inflammatory and haemostatic factorsJ Clin Periodontol2004311252915058371

- KobayashiYNiuKGuanLOral health behavior and metabolic syndrome and its components in adultsJ Dent Res201291547948422378694

- HolmlundAHultheJLindLTooth loss is related to the presence of metabolic syndrome and inflammation in elderly subjects: a prospective study of the vasculature in Uppsala seniors (PIVUS)Oral Health Prev Dent20075212513017722439

- JanketSJBairdAEJonesJANumber of teeth, C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and cardiovascular mortality: a 15-year follow-up study in a Finnish cohortJ Clin Periodontol201441213114024354534

- WitterDJvan Palenstein HeldermanWHCreugersNHKayserAFThe shortened dental arch concept and its implications for oral health careCommunity Dent Oral Epidemiol199927424925810403084

- KressinNRBoehmerUNunnMESpiroA3rdIncreased preventive practices lead to greater tooth retentionJ Dent Res200382322322712598553

- HildebrandtGHDominguezBLSchorkMALoescheWJFunctional units, chewing, swallowing, and food avoidance among the elderlyJ Prosthet Dent19977765885959185051

- HsuKJYenYYLanSJWuYMLeeHEImpact of oral health behaviours and oral habits on the number of remaining teeth in older Taiwanese dentate adultsOral Health Prev Dent201311212113023534036

- NakaOAnastassiadouVPissiotisAAssociation between functional tooth units and chewing ability in older adults: a systematic reviewGerodontology201431316617723170948

- JungJYKimYSKimSKRelationship of vitamin D status with lung function and exercise capacity in COPDRespirology2015578278925868752

- PerssonLJAanerudMHiemstraPSVitamin D, vitamin D binding protein, and longitudinal outcomes in COPDPLoS One2015103e012162225803709

- MartineauARJamesWYHooperRLVitamin D3 supplementation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ViDiCO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trialLancet Respir Med20153212013025476069

- SkaabyTHusemoenLLThuesenBHVitamin D status and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective general population studyPLoS One201493e9065424594696

- KimYThe Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): current status and challengesEpidemiol Health201436e201400224839580