Abstract

Background

Pneumonia may be a major contributor to hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation and influence their outcomes.

Methods

We examined hospitalization rates, health resource utilization, 30-day mortality, and risk of subsequent hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations with and without pneumonia in Denmark during 2006–2012.

Results

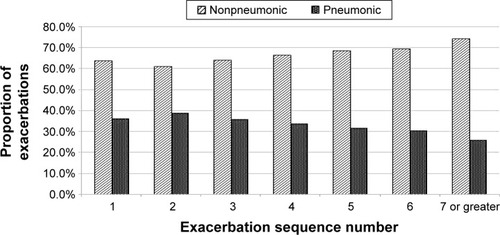

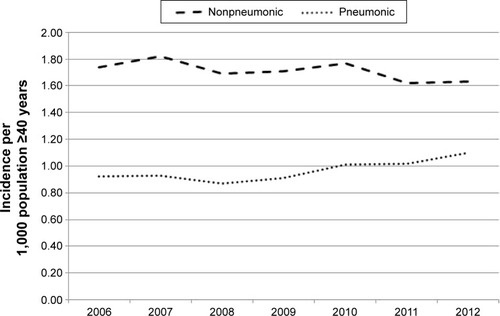

We identified 179,759 hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations, including 52,520 first-time hospitalizations (29.2%). Pneumonia was frequent in first-time exacerbations (36.1%), but declined in successive exacerbations to 25.6% by the seventh or greater exacerbation. Pneumonic COPD exacerbations increased 20% from 0.92 per 1,000 population in 2006 to 1.10 per 1,000 population in 2012. Nonpneumonic exacerbations decreased by 6% from 1.74 per 1,000 population to 1.63 per 1,000 population during the same period. A number of markers of health resource utilization were more prevalent in pneumonic exacerbations than in nonpneumonic exacerbations: length of stay (median 7 vs 4 days), intensive care unit admission (7.7% vs 12.5%), and several acute procedures. Thirty-day mortality was 12.1% in first-time pneumonic COPD exacerbations versus 8.3% in first-time nonpneumonic cases (adjusted HR [aHR] 1.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.17–1.24). Pneumonia also predicted increased mortality associated with a second exacerbation (aHR 1.14, 95% CI 1.11–1.18), and up to a seventh or greater exacerbation (aHR 1.10, 95% CI 1.07–1.13). In contrast, the aHR of a subsequent exacerbation was 8%–13% lower for patients with pneumonic exacerbations.

Conclusions

Pneumonia is frequent among patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations and is associated with increased health care utilization and higher mortality. Nonpneumonic COPD exacerbations predict increased risk of subsequent exacerbations.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is currently the fifth leading cause of death worldwide, and is projected to be the fourth by 2030.Citation1 COPD affects 10%–20% of adults aged 40 years and olderCitation2–Citation4 and is one of the leading causes of hospitalization and high health care costs.Citation5–Citation7 Acute exacerbations are responsible for up to 60% of the costs attributable to COPD,Citation5,Citation8 and they reduce quality of lifeCitation9 and speed disease progression.Citation10

Previous studies have shown that 50%–75% of exacerbations are associated with respiratory infections,Citation11 with an unknown proportion associated with pneumonia. Patients with COPD are at greater risk of developing pneumonia than the general population,Citation12–Citation14 and COPD is an adverse prognostic factor for patients hospitalized with pneumonia.Citation15 However, little is known about the rate of COPD exacerbations with and without pneumonia, or about the impact of pneumonia on severity and outcomes of COPD exacerbations. The few previous studies reached conflicting conclusions, showing either no difference in 30-day mortality among patients with nonpneumonic and pneumonic COPD exacerbationsCitation16,Citation17 or up to 14% increased in-hospital mortality among patients with pneumonic exacerbations.Citation18,Citation19 Pneumonia may worsen the course of COPD exacerbations due to thickening of the blood–gas barrier, leading to pulmonary dysfunction and increased hypoxemia, systemic inflammation, and risk of severe sepsis with hypotension and decreased perfusion of vital organs. Little is known about how pneumonic versus nonpneumonic exacerbations predict the risk of subsequent COPD exacerbations.Citation10

The aim of our study was to examine incidence, health resource utilization, 30-day mortality, and risk of new hospitalizations for COPD exacerbation among patients with successive COPD exacerbations with and without pneumonia in Denmark during 2006–2012.

Material and methods

Setting

Denmark provides its entire population (5.6 million persons) with tax-supported health care and partial reimbursement for prescribed medications. A unique central personal registration number, assigned to all Danish residents at birth or upon immigration, is used to record health care services in various nationwide registries, allowing unambiguous linkage among registries.Citation20 The current nationwide cohort study is based on information from these registries.

Data sources

The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) provides information on all inpatient admissions to hospitals since 1977, and on all outpatient and emergency room visits since 1995.Citation21 For each hospitalization, DNPR files contain data on dates of admission and discharge, surgical procedures performed, if any, and up to 20 discharge diagnoses coded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

Information on all prescription drugs is maintained in the Danish National Health Service Prescription.Citation22 This database records patients’ personal identifier, date of dispensing, and type and quantity of drug prescribed (according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system) each time a prescription is redeemed at any Danish pharmacy.

The Danish Civil Registration System (CRS) records information on date of birth, sex, change of address, date of immigration or emigration, and changes in vital status, with daily updates for all individuals legally residing in Denmark at any time since 1968.Citation20 The CRS allows for complete follow-up of all residents of Denmark.

All ICD and Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes used in this study are provided in the Table S1.

Identification of patients hospitalized for a COPD exacerbation with and without pneumonia

We used the DNPR to identify all first-time acute inpatient hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations in Denmark between 2006 and 2012.Citation6,Citation23 COPD exacerbation was defined as acute admission with either a primary COPD discharge diagnosis or a primary diagnosis of respiratory tract infection, bronchitis, asthma, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or respiratory failure, combined with a secondary diagnosis of COPD listed during the same admission, or a previous primary diagnosis of COPD present within the preceding 10 years.Citation10 We used this expanded definition of COPD exacerbations because restriction to only hospitalizations coded with primary COPD discharge diagnoses results in a documented underreporting of hospitalized COPD exacerbations.Citation23 We excluded patients younger than age 40 years at the time of their first COPD hospitalization, given the low COPD prevalence in young peopleCitation6 and the potential risk of misclassification of asthma as COPD.

We categorized all COPD hospitalizations according to whether or not they included a primary or secondary diagnosis of pneumonia.

Data on confounding factors

We computed Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores for each patient based on all hospital diagnoses in DNPR records within 10 years preceding the date of the first hospitalization for COPD.Citation24 We categorized severity of comorbidity as none (CCI score =0), medium (CCI score =1−2), or high (CCI score ≥3).Citation25 Because alcoholism-related diseases, atrial fibrillation/flutter, asthma, hypertension, osteoporosis, depression, and venous thromboembolism may affect the prognosis of COPD patients and are not included in the CCI, we also identified previous hospitalizations for these conditions. As a marker of social support, we obtained information on marital status (married, never married, divorced, widowed, or unknown) from the CRS.Citation26 To assess the impact of COPD severity, we categorized patients according to their current use of short- and long-acting β-agonists, inhaled corticosteroids (beclomethasone, mometasone, fluticasone, and budesonide), combinations of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β-agonists, and intermittent or continuous use of systemic corticosteroids (Table S1).

Health resource utilization, 30-day mortality, and new exacerbations

We estimated health resource utilization associated with each exacerbation by length of stay (defined as the difference between admission and discharge dates), admission to an intensive care unit, use of mechanical and noninvasive ventilation, inotropics and dialysis, and all-cause 30-day acute readmissions (defined as any readmission within 30 days following the index discharge). Information on these health resource utilization measures was obtained from the DNRP. Up-to-date information on mortality within 30 days of exacerbation was obtained from the CRS.Citation20 Data on new hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations were obtained from the DNRP.

Statistical analysis

We compared patient characteristics and associated health resource utilization among patients hospitalized for a COPD exacerbation, with and without pneumonia. Descriptive statistics were produced using frequencies, proportions, and prevalence proportion ratios (PPRs) for categorical data, and means, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. We then computed overall rates of first COPD exacerbations, with and without pneumonia, as the number of first exacerbations per year divided by the corresponding midyear population above 40 years in Denmark (obtained from Statistics Denmark).

To examine the risk of 30-day mortality and of a new exacerbation, we followed patients from the date of their first hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation until death from any cause, emigration, or December 31, 2012, whichever came first. To assess the effect of each successive exacerbation on the risk of 30-day mortality, we used Cox regression analysis to compute the hazard ratio (HR) of 30-day mortality comparing COPD patients with and without pneumonic exacerbations. Thus, we assessed the risk of death from the admission date with first exacerbation among all patients with a first exacerbation, from the admission date with second exacerbation among all patients with a second exacerbation, and so forth. Age at first exacerbation, sex, CCI score, and respiratory medications as a marker of COPD severity were included as adjustment factors for the effect of pneumonia. The same Cox regression analysis approach was used to assess the effect of each successive COPD exacerbation on the risk of another hospitalization for an exacerbation during follow-up, considering death a competing risk.Citation27 To increase the likelihood of a correct diagnosis of COPD, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we excluded all patients with only a diagnosis of simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis or chronic bronchitis. Furthermore, because patients with pneumonic COPD exacerbations might be coded as having “COPD with acute lower respiratory infection” rather than pneumonia, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we categorized these patients as having a pneumonic exacerbation.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (record no 2012-41-0793). According to Danish law, use of registry data for research purposes does not require informed consent.

Results

Hospitalization rates for COPD exacerbations with and without pneumonia

We identified 179,759 hospitalizations for COPD exacerbations in Denmark during 2006–2012. Of these, 119,877 (66.7%) were nonpneumonic and 59,882 (33.3%) were pneumonic. Among the 52,520 patients with a first-time hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation, 33,552 (63.9%) had a nonpneumonic exacerbation and 18,968 (36.1%) had a pneumonic exacerbation. The proportion of patients with pneumonic exacerbations decreased with an increasing number of exacerbations, reaching 25.6% for seven or more exacerbations (). The annual rate of hospitalizations for nonpneumonic exacerbations decreased by 6% from 1.74 per 1,000 population aged 40 years or older in 2006 to 1.63 per 1,000 population aged 40 years or older in 2012. Concurrently, rates of pneumonic COPD exacerbations increased by 20%, reaching 1.10 per 1,000 population aged 40 years or older in 2012 ().

Patient characteristics and health resource utilization

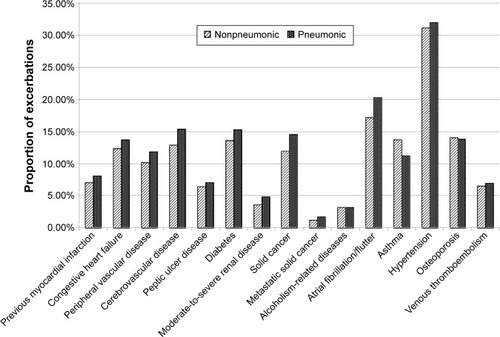

Characteristics of patients with a first-time hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation are listed in . Patients with a pneumonic exacerbation had a slightly lower probability than patients with a nonpneumonic exacerbation of receiving any respiratory medication within the 365 days preceding the index admission (72.0% vs 76.5%). As well, patients with nonpneumonic exacerbations were more likely than patients with pneumonic exacerbations to use oral corticosteroids (26.8% vs 20.7%). Patients with a first-time pneumonic exacerbation were slightly older (median age 75 years, IQR 66–82 years) than patients with a nonpneumonic exacerbation (median age 73 years, IQR 64–80 years), and had a higher prevalence of virtually all comorbidities included in the analysis (57.4% had a CCI score ≥1 compared with 50.7% of patients with nonpneumonic exacerbations) ().

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients with a first-time hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation in Denmark, 2006–2012

Figure 3 Proportion of comorbidities in patients with pneumonic and nonpneumonic COPD exacerbations, Denmark, 2006–2012.

shows the health resource utilization associated with first-time COPD exacerbations. The median length of hospital stay was 4 days (IQR 2–8 days) for patients with a nonpneumonic exacerbation and 7 days (IQR 4–11 days) for patients with a pneumonic exacerbation. Mechanical or noninvasive ventilation was provided to 3.3% and 6.7% of patients with nonpneumonic exacerbations respectively, compared with 6.9% and 9.7% of patients with pneumonic exacerbations. Patients with pneumonic exacerbations were also more likely to receive inotropic therapy (PPR 2.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.94–2.37) or dialysis (PPR 1.74, 95% CI 1.39–2.17), and were slightly more likely to be readmitted for any cause within 30 days following discharge (PPR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00–1.08) compared with patients with nonpneumonic exacerbations ().

Table 2 Health resource utilization among patients with a first-time nonpneumonic or pneumonic COPD exacerbation, Denmark 2006–2012

Thirty-day mortality

Thirty-day mortality was 12.1% in patients with a first-time pneumonic exacerbation and 8.4% in those with a first-time nonpneumonic exacerbation, equivalent to an adjusted HR (aHR) of 1.21 (95% CI 1.17–1.24) after adjusting for age, sex, comorbidity, and respiratory medications (). Presence of pneumonia also predicted increased mortality among patients hospitalized with a second exacerbation (aHR 1.14, 95% CI 1.11–1.18), and up to the seventh and subsequent exacerbation (aHR 1.10, 95% CI 1.07–1.13).

Table 3 Crude and adjusted risk of 30-day mortality according to number of exacerbationTable Footnotea

Among patients with a pneumonic COPD exacerbation, 37.3% had at least one subsequent severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization during median follow-up of 203 days, compared with 43.4% of patients with a nonpneumonic exacerbation during median follow-up of 213 days (). After taking into account death as a competing risk, the corresponding aHR of a subsequent hospitalization for an exacerbation associated with pneumonia was 0.93 (95% CI 0.91–0.96). The time span between successive exacerbations diminished with increasing number of exacerbations, both for pneumonic and nonpneumonic exacerbations. Nonetheless, the aHR of a subsequent exacerbation was 8%–13% lower for patients with pneumonic versus nonpneumonic exacerbations across numbers of exacerbations.

Table 4 Crude and adjusted risk of a subsequent exacerbation according to number of exacerbationTable Footnotea

In the sensitivity analysis excluding patients with bronchitis, presence of pneumonia remained consistently associated with increased risk of death and lower risk of a subsequent exacerbation across numbers of exacerbations (data not shown). At their first-time hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation, 9.5% of patients had a diagnosis of “COPD with acute lower respiratory infection.” Categorizing these patients as having pneumonic exacerbations attenuated the difference between pneumonic and nonpneumonic COPD exacerbations (Table S2).

Discussion

This nationwide population-based cohort study showed a large and apparently increasing burden of pneumonic COPD exacerbations. Approximately 36% of patients hospitalized for a first-time exacerbation also received a pneumonia diagnosis. During 2006–2012, the incidence of first-time hospitalizations for pneumonic exacerbations increased by 20%. Over the same period, the rate of nonpneumonic exacerbations decreased by 6%. Patients with pneumonic exacerbations were older, had more comorbidity, and required more health resources in terms of a prolonged hospital stay, increased use of intensive care, assisted ventilation, inotropic therapy, dialysis, and readmission. Pneumonic exacerbations were also associated with higher 30-day mortality compared with nonpneumonic exacerbations, both in first-time and successive exacerbations, and after adjustment for age, sex, comorbidity, and COPD severity. At the same time, patients with nonpneumonic COPD exacerbations had a slightly higher risk of subsequent hospitalizations for exacerbations than patients with pneumonic exacerbations, regardless of number of exacerbations.

The paucity of data on pneumonic versus nonpneumonic exacerbations to some extent may stem from controversy as to whether or not a case of manifest pneumonia should be considered as part of a COPD exacerbation. Some consider pneumonia and acute exacerbations in COPD patients as separate acute events.Citation16,Citation28 Still, the British Thoracic Society includes COPD patients with X-ray-confirmed pneumonia in their national audit of COPD exacerbations.Citation19 The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease defines an exacerbation as an event in the clinical course of COPD characterized by amplification of the state of chronic inflammation in the airways and acute onset of aggravation of baseline symptoms beyond normal day-to-day variations and leading to a change in medication.Citation29 This broad definition may include a wide range of manifestations, including those of pneumonia.Citation30 Accordingly, in this study, we considered hospitalization for pneumonia to be a COPD exacerbation.

Compared with the few previous studies,Citation17–Citation19,Citation31 we identified a relatively high proportion of patients with a first-time pneumonic COPD exacerbation. In a recent Norwegian study of 1,144 patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbations, 237 (20.7%) had pneumonia defined as a pneumonic infiltrate on X-ray and CRP equal to or above 40 mg/L.Citation17 In the 2008 National UK COPD audit, 16% of patients hospitalized with a COPD exacerbation presented with radiographic consolidation.Citation19 In another study, 23 (9%) patients among 250 patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation had X-ray findings indicating pneumonia.Citation31 In contrast with our study, these studies focused on prevalent rather than incident episodes. We showed that the proportion of pneumonic exacerbations declined with the number of exacerbations, which explains part of the differences in findings. In their study, Steer et alCitation18 included patients with a first-time hospitalization for a COPD exacerbation and found that 299 (33%) of 920 patients were categorized with pneumonic exacerbations based on X-ray findings. This is in line with our finding that 36% of patients in our study who presented with a first-time COPD exacerbation had pneumonia. Also corroborating our findings, earlier studies reported that patients with pneumonic exacerbations tend to be older, have more comorbidity, a longer length of stay, and more assisted ventilation compared with patients with nonpneumonic exacerbations.Citation17–Citation19

In line with the findings of Suissa et al,Citation10 we observed that severe exacerbations appeared to recur progressively sooner after each subsequent severe exacerbation. The reason for the apparently higher risk of subsequent exacerbations among those with nonpneumonic exacerbations is not clear, but might be related to a phenotype associated with persistent and increased propensity for airway and systemic inflammationCitation32 without a propensity for manifest respiratory tract infection. Another explanation may be more intensive antibiotic therapy given to patients with manifest pneumonia, including possible prophylactic use of azithromycin in some patients, which may prevent or delay new COPD exacerbations.Citation33,Citation34 Use of inhaled corticosteroids has been associated with decreased risk of subsequent exacerbations and increased risk for hospitalization with pneumonia.Citation35 However, prior use of inhaled corticosteroids differed little among nonpneumonic and pneumonic first-time admitted patients in our study, and therefore also was unlikely to explain any observed differences in mortality.Citation36 To some extent, the higher risk of subsequent exacerbation in patients following nonpneumonic exacerbations may have been related to the higher mortality during index admission in those with pneumonic exacerbation, leaving fewer frail patients at risk of subsequent exacerbations (depletion of susceptibles).

Our estimates of COPD exacerbation and mortality are based on a nationwide cohort study conducted in a setting in which a national health service provides unfettered access to health care, thus largely eliminating referral and diagnostic biases. Our study included the entire Danish population and had complete follow-up through the use of nationwide registries, so it also avoided the selection biases hampering clinic-based studies.

Our study also has limitations. It is important to note that our results focused only on COPD exacerbations requiring hospitalization. As well, the accuracy of diagnoses of pneumonic and nonpneumonic COPD exacerbation were dependent on proper ICD-10 coding. Previous DNRP validation studies have revealed positive predictive value 92%–100% of ICD codes for primary COPDCitation25 and COPD exacerbations.Citation23 Our data had similarly high accuracy for detecting pneumonia requiring hospitalization (ie, a predictive value of ~90%)Citation37,Citation38 and for the comorbid conditions in the CCI.Citation25 The validity of pneumonia codes associated with COPD has not been well studied. The decline in the proportion of exacerbations with pneumonia over subsequent episodes may suggest that the likelihood of actually having COPD increases with each episode. However, any misclassification between pneumonic and nonpneumonic episodes would tend to diminish observed differences between the two conditions, not changing our conclusions. Another limitation is the lack of clinical data on the length of each exacerbation, making it difficult to differentiate between relapse and recurrence.Citation10,Citation39,Citation40 However, the majority of patients recover within 30 days after the onset of a COPD exacerbation.Citation40 In our data, the median time between hospitalizations ranged from 38 to 213 days, supporting the conclusion that they are in fact recurrent events. We also lacked clinical data on severity of symptoms, airflow limitations, and exercise intolerance, and lifestyle factors such as poor nutrition, alcohol consumption, and tobacco smoking that may influence prognosis.Citation41 However, we were able to control for hospital diagnoses of alcohol-related conditions and many other lifestyle-related diseases including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

We conclude that pneumonia is common in patients hospitalized with acute COPD exacerbations and is associated with increased health resource utilization and poor prognosis compared with patients with nonpneumonic exacerbations. Our results emphasize the need for increased attention to treatment and prevention of pneumonia in patients with COPD.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by a research grant from Pfizer A/S to Aarhus University.

Supplementary materials

Table S1 ICD and ATC classification system codes used in the study

Table S2 Sensitivity analysis categorizing patients with a discharge diagnosis of “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with acute lower respiratory infection” (ICD-10: J44.0) as having a pneumonic COPD exacerbation

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MathersCDLoncarDProjections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030PLoS Med2006311e44217132052

- GershonASWarnerLCascagnettePVictorJCToTLifetime risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a longitudinal population studyLancet2011378979599199621907862

- BuistASMcBurnieMAVollmerWMInternational variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence studyLancet2007370958974175017765523

- FabriciusPLøkkeALouisJVestboJLangePPrevalence of COPD in CopenhagenRespir Med2011105341041720952174

- BildeLRud SvenningADollerupJBaekke BorgeskovHLangePThe cost of treating patients with COPD in Denmark – a population study of COPD patients compared with non-COPD controlsRespir Med2007101353954616889949

- LashTLJohansenMBChristensenSHospitalization rates and survival associated with COPD: a nationwide Danish cohort studyLung20111891273521170722

- LøkkeAHilbergOTønnesenPIbsenRKjellbergJJennumPDirect and indirect economic and health consequences of COPD in Denmark: a national register-based study: 1998–2010BMJ Open201441e004069

- PasqualeMKSunSXSongFHartnettHJStemkowskiSAImpact of exacerbations on health care cost and resource utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with chronic bronchitis from a predominantly Medicare populationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012775776423152680

- DollHMiravitllesMHealth-related QOL in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review of the literaturePharmacoeconomics200523434536315853435

- SuissaSDell’AnielloSErnstPLong-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortalityThorax2012671195796322684094

- SapeyEStockleyRACOPD exacerbations. 2: aetiologyThorax200661325025816517585

- MüllerovaHChigboCHaganGWThe natural history of community-acquired pneumonia in COPD patients: a population database analysisRespir Med201210681124113322621820

- BenfieldTLangePVestboJCOPD stage and risk of hospitalization for infectious diseaseChest20081341465318403661

- RyanMSuayaJAChapmanJDStasonWBShepardDSThomasCPIncidence and cost of pneumonia in older adults with COPD in the United StatesPLoS One2013810e7588724130749

- MolinosLClementeMGMirandaBCommunity-acquired pneumonia in patients with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Infect200958641742419329187

- HuertaACrisafulliEMenéndezRPneumonic and nonpneumonic exacerbations of COPD: inflammatory response and clinical characteristicsChest201314441134114223828375

- AndreassenSLLiaaenEDStenforsNHenriksenAHImpact of pneumonia on hospitalizations due to acute exacerbations of COPDClin Respir J201481939923889911

- SteerJNormanEMAfolabiOAGibsonGJBourkeSCDyspnoea severity and pneumonia as predictors of in-hospital mortality and early readmission in acute exacerbations of COPDThorax201267211712121896712

- MyintPKLoweDStoneRABuckinghamRJRobertsCMUK National COPD Resources and Outcomes Project 2008: patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations who present with radiological pneumonia have worse outcome compared to those with non-pneumonic chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration201182432032721597277

- SchmidtMPedersenLSørensenHTThe Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiologyEur J Epidemiol201429854154924965263

- LyngeESandegaardJLReboljMThe Danish National Patient RegisterScand J Public Health2011397 Suppl303321775347

- JohannesdottirSAHorváth-PuhóEEhrensteinVSchmidtMPedersenLSørensenHTExisting data sources for clinical epidemiology: the Danish National database of reimbursed prescriptionsClin Epidemiol20124130331323204870

- ThomsenRWLangePHellquistBValidity and underrecording of diagnosis of COPD in the Danish National Patient RegistryRespir Med201110571063106821320769

- CharlsonMEPompeiPAlesKLMacKenzieCRA new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validationJ Chronic Dis19874053733833558716

- ThygesenSKChristiansenCFChristensenSLashTLSørensenHTThe predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of PatientsBMC Med Res Methodol20111118321619668

- MorAUlrichsenSPSvenssonEBerencsiKThomsenRWDoes marriage protect against hospitalization with pneumonia? A population-based case-control studyClin Epidemiol2013539740524143123

- AndersenPKGeskusRBde WitteTPutterHCompeting risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfallsInt J Epidemiol201241386187022253319

- CalverleyPMStockleyRASeemungalTAReported pneumonia in patients with COPD: findings from the INSPIRE studyChest2011139350551220576732

- The Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 20152015 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/Accessed August 6, 2015

- WackerhausenLHHansenJGRisk of infectious diseases in patients with COPDOpen Infect Dis J201265259

- LiebermanDLiebermanDGelferYPneumonic vs nonpneumonic acute exacerbations of COPDChest200212241264127012377851

- WedzichaJABrillSEAllinsonJPDonaldsonGCMechanisms and impact of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseBMC Med2013111123281898

- HerathSCPoolePProphylactic antibiotic therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Cochrane Database Syst Rev201311CD00976424288145

- WenzelRPFowlerAAEdmondMBAntibiotic prevention of acute exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med2012367434034722830464

- KewKMSeniukovichAInhaled steroids and risk of pneumonia for chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20143CD01011524615270

- FesticEScanlonPDIncident pneumonia and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A double effect of inhaled corticosteroids?Am J Respir Crit Care Med2015191214114825409118

- SkullSAAndrewsRMByrnesGBICD-10 codes are a valid tool for identification of pneumonia in hospitalized patients aged > or =65 yearsEpidemiol Infect200813623224017445319

- DrahosJVanwormerJJGreenleeRTLandgrenOKoshiolJAccuracy of ICD-9-CM codes in identifying infections of pneumonia and herpes simplex virus in administrative dataAnn Epidemiol20132329129323522903

- DonaldsonGCWedzichaJACOPD exacerbations. 1: EpidemiologyThorax200661216416816443707

- BurgeSWedzichaJACOPD exacerbations: definitions and classificationsEur Respir J200321Suppl 4146S53S

- TorresAPeetermansWEViegiGBlasiFRisk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults in Europe: a literature reviewThorax201368111057116524130229