Abstract

Background

In general, previous studies have shown an association between prior exacerbations and mortality in COPD, but this association has not been demonstrated in the subpopulation of patients in need of assisted ventilation. We examined whether previous hospitalizations were independently associated with mortality among patients with COPD ventilated for the first time.

Patients and methods

In the Danish National Patient Registry, we established a cohort of patients with COPD ventilated for the first time from 2003 to 2011 and previously medicated for obstructive airway diseases. We assessed the number of hospitalizations for COPD in the preceding year, age, sex, comorbidity, mode of ventilation, survival to discharge, and days to death beyond discharge.

Results

The cohort consisted of 6,656 patients of whom 66% had not been hospitalized for COPD in the previous year, 18% once, 8% twice, and 9% thrice or more. In-hospital mortality was 45%, and of the patients alive at discharge, 11% died within a month and 39% within a year. In multivariate models, adjusted for age, sex, mode of ventilation, and comorbidity, odds ratios for in-hospital death were 1.26 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11–1.44), 1.43 (95% CI: 1.19–1.72), and 1.56 (95% CI: 1.30–1.87) with one, two, and three or more hospitalizations, respectively. Hazard ratios for death after discharge from hospital were 1.32 (95% CI: 1.19–1.46), 1.76 (95% CI: 1.52–2.02), and 2.07 (95% CI: 1.80–2.38) with one, two, and three or more hospitalizations, respectively.

Conclusion

Preceding hospitalizations for COPD are associated with in-hospital mortality and after discharge in the subpopulation of patients with COPD with acute exacerbation treated with assisted ventilation for the first time.

Introduction

COPD is a persistent, progressive airflow limitation associated with a chronic airway inflammation and is among the leading causes of mortality and morbidity worldwide, in fact predicted to be the third leading cause of death by 2020.Citation1

An acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD), defined as worsening of symptoms beyond normal day-to-day variation, is associated with increased mortality.Citation1–Citation3 In general, exacerbations are more frequent in severe COPD,Citation4,Citation5 but recent studies show that the number of exacerbations varies extensively among patients with COPD with similar lung function in stable phases. Nevertheless, exacerbations are the best predictor of their own recurrence.Citation3,Citation4,Citation6 It has been suggested that an inherent “frequent-exacerbation phenotype” with a distinct pathophysiology might explain at least parts of the extensive clinical variability.Citation4,Citation7 Previous accumulated exacerbations have been shown to predict not only new exacerbations but also mortality. This prediction is independent of stable phase lung function impairment, and mortality increases by each subsequent exacerbation.Citation5,Citation8–Citation11 It is not known whether the association between previous exacerbations and mortality is independent of the degree of acute illness. Patients subjected to assisted ventilation constitute a group whose acute illness is severe, and the association between previous exacerbations and mortality in this group has not been elucidated.

The overall short-term mortality among patients with acute exacerbations ranges from 2.1% to 20.4%,Citation9,Citation12,Citation13 but patients with severe acute COPD admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) are particularly at risk with a 6-month mortality ranging from 25% to 40%.Citation12,Citation14,Citation15 In-hospital mortality rates for patients being ventilated are 5%–25% but higher in relation to invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) than to noninvasive mechanical ventilation (NIV).Citation16–Citation20 Predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with COPDCitation12,Citation21,Citation22 are age, comorbidities, and end-stage COPD with concomitant organ dysfunctions. Lung function impairment in stable phase is in itself a poor predictor of short-term mortality following exacerbationsCitation8,Citation23 but is associated with long-term mortality.Citation24 On the other hand, acidosis, which mirrors acute derangement, predicts short-term but not long-term mortality.Citation12 In patients admitted to ICU, acute derangement is of major importance regarding both short-termCitation25,Citation26 and intermediate-term survival,Citation15 but long-term survival studies have been conflicting with regard to independent risk predictors.Citation14,Citation27–Citation31

The aim of this study was to investigate whether the frequency of previous hospitalizations for AECOPD can predict in-hospital mortality and mortality after discharge in an inception cohort of patients with COPD treated with assisted ventilation for the first time. We hypothesized that frequent COPD hospitalizations were associated with excess mortality following assisted ventilation.

Patients and methods

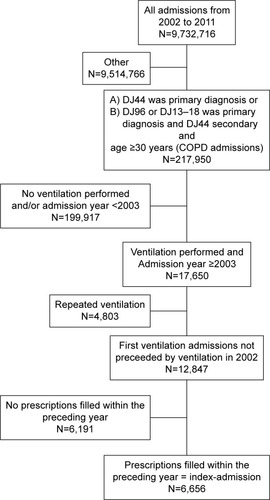

All hospitalizations from 2002 to 2011 were identified in the Danish National Patient Registry. Successive hospitalizations were merged if the discharge date of the first and the admission date of the second were identical. AECOPD hospitalizations were defined as hospitalizations with either a primary diagnosis of COPD (International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition [ICD-10]: DJ44) or a complex of either acute respiratory failure (ICD-10: DJ96) or pneumonia (ICD-10: DJ13–18) as the primary diagnosis and COPD as a secondary diagnosis as described by Thomsen et al.Citation32 In general, hospitalizations related to diseases of the respiratory system (respiratory hospitalizations) were identified by a primary diagnosis within the entire ICD-10 DJ-spectrum. No attempts were made to distinguish between admissions for exacerbations with and without pneumonia. Patients <30 years of age were excluded to minimize inclusion of misclassified asthma. First time ventilation was defined as the first AECOPD hospitalization where assisted ventilation was performed, but first time ventilations in 2002 were discarded as no specific procedure code for NIV was accessible till 2003. In the National Register of Medicinal Product Statistics, all prescriptions in the year preceding first time hospitalizations were identified. By ATC code “R03”, drugs for obstructive airway diseases were identified. First time ventilation was classified as the index hospitalization if a prescription was redeemed within 1 year before. Any patient with an index hospitalization was included in the cohort (). Mode of ventilation at the index hospitalization was characterized as either “IMV” (BGDA0) or “NIV” (BGDA1). The categories were mutually exclusive and hierarchically assigned so that IMV overruled NIV, if both were registered.

The number of AECOPD and respiratory system-related hospitalizations in the year preceding the index hospitalization was counted. Charlson comorbidity score based on diagnoses made during hospitalizations and outpatient visits 10 years prior to the discharge from the index hospitalization were assigned to individual diseases ad modum Radovanovic et alCitation33 and grouped in three with 1, 2, or 3+ points, respectively, as per definition all patients received one point for having COPD.

Information on day of death was obtained from the Danish Civil Registration System. Each patient was followed until the time of death or censured by December 31, 2013. Informed consent was not required according to Danish legislation.

General characteristics between groups were compared by chi-square test (character variables) and Kruskal–Wallis test (continuous variable). For analysis of in-hospital mortality, logistic regression was used, and for analysis of mortality beyond discharge, Cox proportional hazards models were used. In both models, continuous variables were tested for linearity, and in the Cox model, dependency of the estimates on time was evaluated by the Schoenfeld residuals. Interactions a priori were considered relevant, that is, interactions between previous hospitalizations, and age, sex, and mode of ventilation, respectively, were tested for by comparisons of likelihood. P-values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS 9.4© (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R© Version 3.1.1.

Results

The population consisted of 6,656 patients (). Of these, 65% had not been hospitalized for AECOPD in the preceding year, 18% had been hospitalized once, 8% twice, and 9% thrice or more. The proportion excluded was 50% in the group of patients not hospitalized in the previous year and 44%, 41%, and 45% in the group hospitalized once, twice, and thrice, respectively. Mortality rates are shown in and . The annual number of first time ventilations for COPD exacerbation increased from 355 in 2003 to 1,236 in 2011.

Table 1 Characteristics of included patients at baseline by number of COPD hospitalizations in the previous year

Table 2 In-hospital mortality by number of COPD hospitalizations in the previous year

Table 3 Mortality after discharge by number of COPD hospitalizations in the previous year

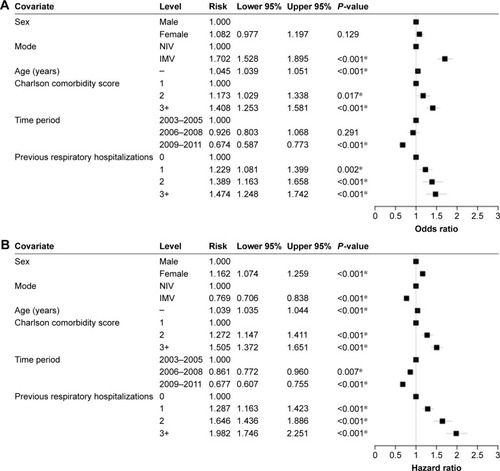

Increasing age, high Charlson comorbidity score, and IMV were the risk factors for in-hospital mortality. The risk decreased during the study period. For all patients, in-hospital mortality was associated with the number of previous AECOPD hospitalizations. The odds ratios, compared to no previous hospitalizations, were 1.26 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11–1.44) with one hospitalization, 1.43 (95% CI: 1.19–1.72) with two hospitalizations, and 1.56 (95% CI: 1.30–1.87) with three or more hospitalizations (). The risk associated with three or more hospitalizations was significantly higher than the risk associated with one hospitalization (P=0.04).

Figure 2 Logistic regression model of in-hospital mortality.

Abbreviations: NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation.

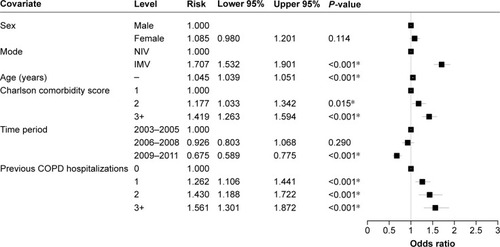

Mortality after discharge from hospital was associated with female sex, increasing age, Charlson comorbidity score, and NIV. The risk decreased during the study period. For all patients, the number of previous AECOPD hospitalizations was associated with an increased mortality after discharge compared to no previous hospitalizations with a hazard ratio of 1.32 (95% CI: 1.19–1.46) with one hospitalization, 1.76 (95% CI: 1.52–2.02) with two hospitalizations, and 2.07 (95% CI: 1.80–2.38) with three or more hospitalizations (). The risks associated with two and with three or more hospitalizations were significantly higher than the risk associated with one hospitalization (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively).

Figure 3 Cox proportional hazards model of mortality after discharge.

Abbreviations: NIV, noninvasive mechanical ventilation; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation.

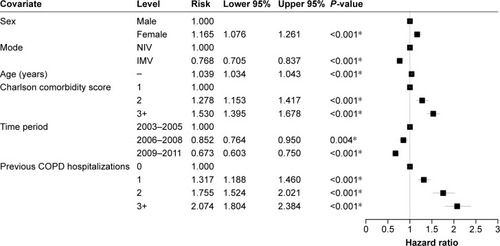

The associations with both in-hospital and after-discharge mortality showed the same trends, though weaker, when, instead of AECOPD hospitalizations, respiratory hospitalizations were included in the model ().

Discussion

In this study of patients ventilated for COPD for the first time, an increasing number of hospitalizations in the preceding year were associated with increased overall mortality. We found significant odds ratios for in-hospital death ranging from 1.3 to 1.6 with increasing number of hospitalizations with COPD exacerbations within the previous year. To our knowledge, this association has not been studied in this subgroup of patients. A number of studies have examined the association between previous exacerbations and mortality in other COPD subpopulations, and in some of these, the association was far stronger than what we found.

Hospital contact for exacerbation within the previous year was associated with adverse events within a month, odds ratio 3.9 (95% CI: 1.6–9.9).Citation22 Likewise, having had at least two hospitalizations within the previous 2 years was associated with 30 days mortality, odds ratio 3.6 (95% CI: 2.5–5.2).Citation34 Among ICU admitted patients with COPD, two or more exacerbations within the previous year were associated with in-hospital mortality, odds ratio 9.1 (95% CI: 1.02–81.1).Citation11 Apart from different outcome measurements, the discrepancy in the magnitude of the correlations might be explained by different case mixes. Patients with end-stage COPD, which presumably have more frequent exacerbations, may to some extent have been excluded from our cohort due to advancement orders that ruled out ventilation. Whether the stage of stable phase COPD modifies the correlation between the number of hospitalizations and short-term mortality needs to be further evaluated.

Among patients with COPD in Denmark, Schmidt et alCitation35 found significant association between neither previous overall exacerbations nor previous hospitalized exacerbations and 30-day mortality after hospitalization for exacerbation upon adjustment for age, sex, comorbidities, and previous medication. Patients in this cohort, in contrast to those included in ours, were dissimilar with regard to the acute severity of the exacerbation due to a case mix of ventilated and nonventilated patients. Moreover, first time and repeated hospitalizations were evaluated together, and redeemed prescriptions for obstructive airway diseases medication were not a criterion for inclusion. Another study of 3-month mortality showed that previous hospitalizations were not a significant predictor of mortality upon inclusion of markers of acute derangement and performance status.Citation36 It is possible, though, that the decision of admitting a patient with any given degree of acute illness depends on performance status, thus masking an association between previous hospitalizations and mortality.

In our study population, mortality after discharge was associated with previous exacerbations with hazard ratios in the range of 1.3–2.0 for one and three or more hospitalizations, respectively. The aforementioned Danish studyCitation35 also found a significant association between long-term mortality and the number of COPD exacerbations. The strength of the association is comparable to what we found and to what was found in a Spanish study.Citation37

A large American studyCitation38 found a lower hazard ratio after discharge of 1.14 by each previous hospitalization in a 1-year period. However, the inclusion criteria as well as the case mix were profoundly different from ours, and in addition, immortal time bias might partly account for the estimate being lower than ours. No independent association was found in another study by Almagro et al,Citation39 but stable phase lung function impairment correlated strongly with prognosis and might have masked an association.

Our study confirmed the importance of age and comorbidity, while sex was only associated with mortality after discharge. Mortality risk decreased with time. IMV as a mode of ventilation predicted death before discharge independently, whereas NIV predicted time to death after discharge. IMV is mainly initiated in patients with severe acute derangement, which probably accounts for the associated higher in-hospital mortality compared to NIV. That this relation is reversed after discharge can have several explanations, among those that patients discharged alive after IMV treatment had undergone harder selection.

In comparison with other studies, our estimate of in-hospital mortality of ventilated patients is high,Citation16,Citation31,Citation40 but this might partly be explained by inclusion in our study of patients with COPD with pneumonia, which confers a large additional risk.Citation41

The association between treatment year and risk might be explained by increasingly aggressive strategies for stable phase medication and for ventilation during exacerbations. Assuming that both medication and ventilation have mainly gained a stronger foothold among less afflicted patients with COPD, gradual rarefication of mortality by the inherently favorable prognosis of this group can explain the improvement of prognosis.Citation42

The strengths of our study are the large number of patients and the high reliability of the Danish medical registers, which is well established for a number of diagnoses,Citation43 among those the COPD diagnosis applied here (a positive predictive value of 92%),Citation32 procedures,Citation44 and vital status.Citation45 In addition, the inherent ability to track unique patient courses virtually eliminates all but emigration as loss to follow-up.

Our study has noteworthy limitations. Misclassification is in our data set especially problematic with regard to the calculated comorbidity, where completeness of registration will be highest among frequently hospitalized patients. However, the use of Charlson comorbidity score has been shown to yield acceptable precision when calculated from registers,Citation46 although the sensitivity of secondary diagnoses in the National Patient Registry is known to be low.Citation47 We speculated whether the number of previous hospitalizations decided by our method could underestimate the number of hospitalizations as the propensity to register a COPD diagnosis in connection with a hospitalization might depend on the COPD stage. Such misclassification might even be differential as only previously admitted patients could be misclassified. To test this, we substituted respiratory hospitalizations for COPD hospitalizations, which did not materially change the results.

We chose to include only patients with COPD who had redeemed prescriptions for obstructive airway diseases medication within the year preceding ventilation. This excluded 49% of all patients whose hospitalizations would have qualified as index hospitalizations. This might reflect not only low compliance but also the inclusion of patients with breathing difficulties whose history was suggestive of COPD but who did not have symptoms on a daily basis. It is surprising and concerning that the proportion of patients who had not redeemed medication was almost equal in patients who had no previous admissions and in patients who had been repeatedly hospitalized. Exclusion in this case is a trade-off between generalizability and validity. It is generally assumed that previous medication acts as a proxy for previously recognized COPD, and thereby to some extent as a marker of stable phase disease severity. Previously, it has been shown that majority of the COPD population are unaware of their diseaseCitation48 and that a considerable proportion of even patients with advanced disease (25%) do not receive appropriate treatment.Citation49 Even so, in general, the unrecognized cases have less advanced disease, are hospitalized less frequently after the hospitalization where the diagnosis was established,Citation50 and have less severe symptoms prior to exacerbations.Citation50

Other limitations to our study are the lack of information on lung function prior to the hospitalization, the degree of acute physiological derangement, and the extent of limitations in care. Differences in underlying acute and chronic lung function impairment might confound the association between previous hospitalizations and mortality. However, we do consider this to be partly ameliorated by the inclusion of only such patients as had been offered ventilation upon clinical decision. Wildman et alCitation51 have shown that clinicians are overly pessimistic when predicting the survival of patients with COPD on hospitalization to specialized respiratory units or ICUs, so it must be assumed that the instigation of assisted ventilation, at least invasive ventilation, among patients with very severe lung function impairment is limited. As for variation in severity of present respiratory failure, any subject hospitalized to our selected study population had an overall acute derangement warranting assisted ventilation, and it must be assumed that the gas exchange was considerably impaired in most of our subjects. In pace with the dissemination of NIV as an accessible treatment option, NIV has to some extent become the interventional limit for a group of frail, elderly patients with often advanced COPD.Citation19 We did not have access to information on do-not-intubate-orders, but a previous Danish study found such orders in 10% of NIV patients.Citation52 Presumably, a subpopulation of patients with short expected life span diluted the survival in the NIV group.

Conclusion

In conclusion, among the patients with COPD with acute exacerbation treated with assisted ventilation for the first time, the number of hospitalizations for COPD in the preceding year is associated with increased mortality in-hospital as well as after discharge. Our study did not aim at identifying patients in whom assisted ventilation is futile. Nonetheless, it emphasizes the importance of the clinical trajectory for the outcome following ventilation in a group of patients whose mortality is very high.

Author contributions

APTP had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CTP, UMW, and BSR contributed substantially to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease2015

- KruisALStällbergBJonesRCMPrimary care COPD patients compared with large pharmaceutically-sponsored COPD studies: an UNLOCK validation studyPLoS One201493

- MüllerovaHMaselliDJLocantoreNECLIPSE InvestigatorsHospitalized exacerbations of COPDCHEST J20151474999

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoAet alEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) InvestigatorsSusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- Garcia-AymerichJSerra PonsIManninoDMMaasAKMillerDPDavisKJLung function impairment, COPD hospitalisations and subsequent mortalityThorax201166758559021515553

- VestboJAgustiAWoutersEFMShould we view chronic obstructive pulmonary disease differently after ECLIPSE? A clinical perspective from the study teamAm J Respir Crit Care Med201418991022103024552242

- HanMKAgustiACalverleyPMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPDAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182559860420522794

- Soler-CataluñaJJMartínez-GarcíaMARomán SánchezPSalcedoENavarroMOchandoRSevere acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2005601192593116055622

- JohannesdottirSAChristiansenCFJohansenMBHospitalization with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated health resource utilization: a population-based Danish cohort studyJ Med Econ201316789790623621504

- SuissaSDell’AnielloSErnstPLong-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortalityThorax2012671195796322684094

- AburtoMEstebanCMorazaFJAguirreUEgurrolaMCapelasteguiACOPD exacerbation: mortality prognosis factors in a respiratory care unitArch Bronconeumol2011472798421316833

- SinganayagamASchembriSChalmersJDPredictors of mortality in hospitalized adults with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review and meta-analysisAnn Am Thorac Soc2013102818923607835

- EriksenNHansenEFMunchEPRasmussenFVVestboJChronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Admission, course and prognosisUgeskr Laeger2003165373499350214531348

- BatzlaffCMKarpmanCAfessaBBenzoRPPredicting 1-year mortality rate for patients admitted with an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to an intensive care unit: an opportunity for palliative careMayo Clin Proc201489563864324656805

- MesserBGriffithsJBaudouinSVThe prognostic variables predictive of mortality in patients with an exacerbation of COPD admitted to the ICU: an integrative reviewQJM2012105211512622071965

- LindenauerPKStefanMSShiehM-SPekowPSRothbergMBHillNSOutcomes associated with invasive and noninvasive ventilation among patients hospitalized with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJAMA Intern Med2014112

- StefanMSNathansonBHHigginsTLComparative effectiveness of noninvasive and invasive ventilation in critically III patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCrit Care Med20151

- ChandraDStammJATaylorBOutcomes of noninvasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United States, 1998–2008Am J Respir Crit Care Med2012185215215922016446

- RobertsCMStoneRABuckinghamRJPurseyNALoweDNational Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Resources and Outcomes Project Implementation GroupAcidosis, non-invasive ventilation and mortality in hospitalised COPD exacerbationsThorax2011661434821075776

- DresMTranT-CAegerterPInfluence of ICU case-volume on the management and hospital outcomes of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCrit Care Med20134181884189223863223

- HoT-WTsaiY-JRuanS-YHINT StudyGroupIn-hospital and one-year mortality and their predictors in patients hospitalized for first-ever chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a nationwide population-based studyPLoS One2014912e11486625490399

- MatkovicZHuertaASolerNPredictors of adverse outcome in patients hospitalised for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespiration2012841172622327370

- LangePMarottJLVestboJPrediction of the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, using the new GOLD classification: a study of the general populationAm J Respir Crit Care Med20121861097598122997207

- TerzanoCContiVDi StefanoFComorbidity, hospitalization, and mortality in COPD: results from a longitudinal studyLung2010188432132920066539

- UcgunIMetintasMMoralHAlatasFYildirimHErginelSPredictors of hospital outcome and intubation in COPD patients admitted to the respiratory ICU for acute hypercapnic respiratory failureRespir Med20061001667415890508

- AfessaBMoralesIJScanlonPDPetersSGPrognostic factors, clinical course, and hospital outcome of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease admitted to an intensive care unit for acute respiratory failureCrit Care Med20023071610161512130987

- ChristensenSRasmussenLHorváth-PuhóELenler-PetersenPRhodeMJohnsenSPArterial blood gas derangement and level of comorbidity are not predictors of long-term mortality of COPD patients treated with mechanical ventilationEur J Anaesthesiol200825755055618413008

- BerkiusJSundhJNilholmLFredriksonMWaltherSMLong-term survival according to ventilation mode in acute respiratory failure secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multicenter, inception cohort studyJ Crit Care2010253539.e13539.e1820381291

- GroenewegenKHScholsAMWJWoutersEFMMortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPDChest2003124245946712907529

- BreenDChurchesTHawkerFTorzilloPJAcute respiratory failure secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated in the intensive care unit: a long term follow up studyThorax2002571293311809986

- NevinsMLEpsteinSKPredictors of outcome for patients with COPD requiring invasive mechanical ventilationChest200111961840184911399713

- ThomsenRWLangePHellquistBValidity and underrecording of diagnosis of COPD in the Danish National Patient RegistryRespir Med201110571063106821320769

- RadovanovicDSeifertBUrbanPValidity of Charlson Comorbidity Index in patients hospitalised with acute coronary syndrome. Insights from the nationwide AMIS Plus registry 2002–2012Heart201410028829424186563

- FaustiniAMarinoCD’IppolitiDForastiereFBelleudiVPerucciCAThe impact on risk-factor analysis of different mortality outcomes in COPD patientsEur Respir J200832362963618448492

- SchmidtSAJJohansenMBOlsenMThe impact of exacerbation frequency on mortality following acute exacerbations of COPD: a registry-based cohort studyBMJ Open20144e006720e006720

- RobertsCMLoweDBucknallCERylandIKellyYPearsonMGClinical audit indicators of outcome following admission to hospital with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax20025713714111828043

- AlmagroPCalboEOchoa de EchagüenAMortality after hospitalization for COPDChest200212151441144812006426

- McGhanRRadcliffTFishRSutherlandERWelshCMakeBPredictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPDChest200713261748175517890477

- AlmagroPCabreraFJDiezJComorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD: the EPOC en Servicios de medicina interna (ESMI) studyChest201214251126113323303399

- Ai-PingCLeeK-HLimT-KIn-hospital and 5-year mortality of patients treated in the ICU for acute exacerbation of COPD: a retrospective studyChest2005128251852416100133

- OngelEAKarakurtZSalturkCHow do COPD comorbidities affect ICU outcomes?Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201491187119625378919

- LindenauerPKLaguTShiehMSPekowPSRothbergMBAssociation of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003–2009JAMA J Am Med Assoc2012307131405

- ThygesenSKChristiansenCFChristensenSLashTLSørensenHTThe predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of PatientsBMC Med Res Methodol20111118321619668

- Blichert-HansenLNielssonMSNielsenRBChristiansenCFNørgaardMValidity of the coding for intensive care admission, mechanical ventilation, and acute dialysis in the Danish National Patient Registry: a short reportClin Epidemiol2013591223359787

- SchmidtMPedersenLSørensenHTThe Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiologyEur J Epidemiol201429854154924965263

- QuanHParsonsGAGhaliWAValidity of information on comorbidity derived rom ICD-9-CCM administrative dataMed Care200240867568512187181

- KümlerTGislasonGHKirkVAccuracy of a heart failure diagnosis in administrative registersEur J Heart Fail200810765866018539522

- SorianoJBZielinskiJPriceDScreening for and early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseLancet2009374969172173219716965

- HansenJGPedersenLOvervadKOmlandØJensenHKSørensenHTThe Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among Danes aged 45–84 years: population-based studyCOPD20085634735219353348

- BalcellsEGimeno-SantosEde BatlleJCharacterisation and prognosis of undiagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients at their first hospitalisationBMC Pulm Med2015151425595204

- WildmanMJSandersonCGrovesJImplications of prognostic pessimism in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma admitted to intensive care in the UK within the COPD and asthma outcome study (CAOS): multicentre observational cohort studyBMJ20073357630113217975254

- TitlestadILLassenATVestboJLong-term survival for COPD patients receiving noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failureInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2013821521923650445