Abstract

Background

Two-thirds of older people suffer from chronic pain and finding valid treatment options is essential. In this 1-yearlong investigation, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of prolonged-release oxycodone–naloxone (OXN-PR) in patients aged ≥70 (mean 81.7) years.

Methods

In this open-label prospective study, patients with moderate-to-severe noncancer chronic pain were prescribed OXN-PR for 1 year. The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved ≥30% reduction in pain intensity after 52 weeks of treatment, without worsening bowel function. The scheduled visits were at baseline (T0), after 4 weeks (T4), and after 52 weeks (T52).

Results

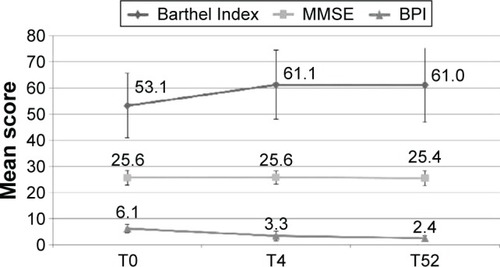

Fifty patients completed the study. The primary endpoint was achieved in 78% of patients at T4 and 96% at T52 (P<0.0001). Pain intensity, measured on a 0–10 numerical rating scale, decreased from 6.0 at T0 to 2.8 at T4 and to 1.7 at T52 (P<0.0001). Mean daily dose of oxycodone increased from 10 to 14.4 mg (T4) and finally to 17.4 mg (T52). Bowel Function Index from 35.1 to 28.7 at T52. No changes were observed in cognitive functions (Mini-Mental State Examination evaluation), while daily functioning improved (Barthel Index from 53.1 to 61.0, P<0.0001). The Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised score at 52 weeks was 2.6 (standard deviation 1.6), indicating a low risk of aberrant medication-related behavior. In general, OXN-PR was well tolerated.

Conclusion

This study of the long-term treatment of chronic pain in a geriatric population with OXN-PR shows satisfying analgesic effects achieved with a stable low daily dose, coupled with a good safety profile and, in particular, with a reduction of constipation, often present during opioid therapy. Our findings support the indications of the American Geriatrics Society, suggesting the use of opioids to treat pain in older people not responsive to acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Introduction

Managing chronic pain is, in itself, a complex task due to the wide range of painful clinical pictures and the limits of therapeutic tools. The World Health Organization (WHO) first introduced the three-step analgesic ladder in 1986 with the aim of creating a framework for the rational use of analgesics. The ladder consists of the use of nonopioid analgesics for mild pain (step 1), “weak” opioids, like codeine and tramadol, associated generally with nonopioids for moderate pain (step 2), and “strong” opioids with or without nonopioids for strong pain (step 3).Citation1 On one hand, adherence to the analgesic ladder and other pain guidelines is relatively infrequent, and on the other hand, the clinical usefulness of step 2 medications (weak opioids such as tramadol, codeine, hydrocodone) has been challenged in the literature, and the routine use of step 2 medications may be associated with disadvantages. In a 2010 Cochrane review, opioidCitation2 therapy for chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) was considered controversial due to concerns regarding long-term effectiveness and safety, particularly the risk of side effects, tolerance, dependence, or abuse. However, there are data, supported by weak evidence, showing that patients who were able to continue opioids for a long term experienced clinically significant pain relief.Citation2 When CNCP affects older people, critical issues such as comorbidities, coprescription of medication, frailty, cognitive dysfunction, and chronic illness can further increase, and providing effective pain management requires particular care in the choice of drugs and doses. On this basis, in 1998, the American Geriatrics Society published a clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic pain in older populations,Citation3 recommending a cautious approach to the use of opioids. Furthermore, current British guidelines for the treatment of pain in older people acknowledge the validity of skipping step 2 of the WHO’s pain ladder, according to which the use of strong opioids at low doses is a valid option for the treatment of moderate-to-severe pain not adequately controlled with acetaminophen (paracetamol) and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).Citation4 During therapy with opioids, the most common adverse events are related to bowel dysfunction, and include constipation; straining; hard, dry stools; incomplete evacuation; bloating; and increased gastric reflux. In older patients, constipation naturally increases with age and a concomitant opioid treatment can worsen the problem.Citation2,Citation5–Citation11 Given that chronic pain affects ~60% of people aged more than 65 years,Citation12 the problem is imperative and requires a combination of three key aspects to be addressed: to relieve pain, to limit adverse events, and to pay attention to the advanced age.

The combination of oral prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone (OXN-PR)Citation13 in a fixed 2:1 ratio was developed to mitigate the gastrointestinal adverse effects of opioids, while preserving the aim to reduce pain. The pharmacological basis of this agonist–antagonist association has been widely described elsewhere.Citation14 The clinical effects of the oral OXN-PR combination were shown in a number of controlled randomized trialsCitation15–Citation17 and in observational studiesCitation18,Citation19 including patients with cancer and noncancer-related chronic pain. These studies have provided evidence of effective analgesia and a significant reduction in the incidence of opioid-induced constipation, with an improvement in compliance and quality of life.Citation16,Citation20 Two 52-week extension phase open-label trials assessing the long-term efficacy and safety of OXN-PR in managing CNCP demonstrated stable relief of pain with tolerable side effects.Citation6,Citation9

There are scarce data from the literature addressing pain treatment with OXN-PR in older patients. This study presents the results of the 52-week extension phase of a 4-week prospective observational study,Citation21 evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of OXN-PR in older patients naïve to strong opioids, who were recruited by an Italian geriatric unit specialized in physical rehabilitation. Here, the long-term analgesic effects and safety of OXN-PR, together with the functional and cognitive status and the level of opioid dependence are analyzed.

Materials and methods

This was a single-center, noncontrolled, prospective observational study performed at Santa Margherita Institute of Pavia, Italy, to assess the long-term analgesic efficacy and safety of OXN-PR in older people with moderate-to-severe CNCP. The 4-week findings of the study have been previously reported.Citation21 Briefly, this was an open-label prospective study assessing older patients naïve to strong opioids with moderate-to-severe chronic pain. Patients were prescribed OXN-PR at an initial dose of 10/5 mg daily for 4 weeks, and in case of insufficient analgesia, the initial daily dose could be increased gradually. Changes in cognitive state, daily functioning, quality of life, constipation, and other adverse events were assessed. Low-dose OXN-PR was found effective and well tolerated in the short term, without affecting the cognitive status and bowel function.Citation21 The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. Policlinico San Matteo of Pavia Ethics Committee approved the study protocol and all patients provided written informed consent.

Patient population

Patients who completed the 4 weeks’ observation,Citation21 achieving at least partial pain control (no severe pain, ie, numerical rating scale [NRS] <7) in the absence of major side effects entered the extension phase and received OXN-PR for up to 52 weeks. Furthermore, consecutive outpatients referred to the center from January to March 2014 and receiving a new prescription for OXN-PR were included in this 52-week observation.

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they met the following criteria: age ≥70 years; presence of chronic pain lasting ≥3 months, average pain intensity (PI) score ≥4 measured on a 0–10 NRS; requiring around-the-clock WHO step 3 opioids (strong opioids) despite analgesic treatment (NSAIDs, acetaminophen alone or in combination with low doses of codeine); no previous treatment with around-the-clock strong opioids; and absence of contraindications to oxycodone use.

Patients with the following were excluded: inability to take oral medication; symptomatic cerebral metastases; known psychiatric disease; cognitive impairment or dementia not allowing appropriate pain assessment (scores <18 at Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE; range: 0–30], indicating moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment);Citation22 severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other respiratory disease with hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia; paralytic ileus; moderate or severe liver insufficiency (total bilirubin ≥1.5 mg/dL); moderate or severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min according to Cockcroft–Gault formula); or hypersensitivity to the active substances or to any of the excipients of the study medication.

Patients were evaluated at baseline (T0), 4 weeks (T4), and after 52 weeks (T52; final observation).

Assessment and endpoints

Demographic information and selected clinical data were recorded at baseline: age, sex, and previous treatments for pain. The PIs, assessed on a verbally administered 0–10 point NRS referred to the last 7 days, were recorded as pain at rest, pain during movement, pain during the day, and pain at nighttime, at baseline (T0), after 4 weeks (T4), and after 52 weeks (T52). A mean of the four PIs was reported as mean of each single day assessment for the four daily items.

Bowel function, evaluated by the Bowel Function Index (BFI) according to Rentz et al,Citation23 was recorded at the same time points. The BFI, a measure of general bowel function recently validated as a reproducible tool that detects clinically meaningful changes in opioid-induced constipation, comprises scores ranging from 0 (free from symptoms) to 100 (most severe symptoms). In patients with chronic pain, normal bowel function is defined as a BFI of ≤29, and a ≥12-point change in BFI score represents a clinically meaningful change in constipation severity.

Cognitive state was assessed using the MMSE (normal value >25).Citation24 Daily functioning, evaluated by the Barthel Index (the maximum score achievable, equal to 100, indicates that the patient can perform all activities independently)Citation25 and the measure of interference of pain in the patient’s life, was evaluated at T0, T4, and T52 by seven items from the validated Italian version of the Brief Pain Inventory-Short FormCitation26 (general activity, walking ability, normal work, moods, enjoyment of life, sleeping, and relations with other people) with an 11-point NRS for each item, ranging from 0= no impairment to 10= most severe impairment.Citation27

Safety evaluations were performed at T4 and T52 by recording the presence and severity (on a verbally administered 0–10 point NRS, where 0= absence and 10= extreme severity) of symptoms commonly related to opioid treatment (nausea/vomiting, dry mouth, dizziness, drowsiness, and pruritus) and any other treatment-related adverse events that occurred or worsened in intensity and/or frequency after the first intake of OXN-PR.

The patient’s risk for opioid abuse was assessed at T52 using the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R), a 24-item, self-administered questionnaire designed to predict aberrant medication-related behaviors among persons with chronic pain. Items are rated from 0= never to 4= very often, and summed to generate the total SOAPP-R score, which ranges from 0 to 96.Citation28

The starting dose of OXN-PR at T0 was 5/2.5 mg of naloxone twice a day. During the 4-week observation (T4), the daily dose could be modified up to a maximum of 10/5 mg twice a day in case of insufficient analgesia. To control pain, all patients were instructed to take a rescue dose of acetaminophen 500 mg when they did not achieve satisfactory pain control. In case of rescue medication dosing more than twice in 1 day, patients were instructed to contact our center. Any other medications needed for the treatment of any other concomitant medical condition, including laxatives, were continued. During the 52-week extension phase, all patients received open-label OXN-PR and the starting dose of OXN-PR was the effective analgesic dose of OXN that the patient received at the end of the previous 4-week observation. Dose titration was permitted to a maximum of 40 mg/day at the discretion of the investigator. Concomitant physical and rehabilitative therapy was allowed throughout the protocol.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of responders, namely, patients who achieved a ≥30% reduction in PI scoreCitation29 (evaluated as mean of each single day assessment for the four daily items of the four pain measures) from baseline to 52 weeks of treatment with OXN-PR without a worsening of bowel function.

Secondary endpoints were: the values of BFI score, MMSE, Barthel Index, Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), and SOAPP-R at T52, the proportion of patients reporting adverse events at T52, their severity, and the absolute daily dose of OXN-PR at T52.

Statistical analysis

In the descriptive analysis, absolute frequency was used for categorical variables and central trend and dispersion measurements (mean or median, standard deviations) were used for quantitative continuous variables. Normality of data distribution was verified by the Shapiro–Wilk test.

The significance of difference between pairs of continuous variables was evaluated by the Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon test, as appropriate. Changes in continuous variables over time were evaluated by analysis of variance (with a post hoc Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons). Changes over time in categorical variables were evaluated with the Cochran’s Q test, the Friedman test, or repeated measures analysis of variance, when appropriate. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed with the Statistical Analysis Software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

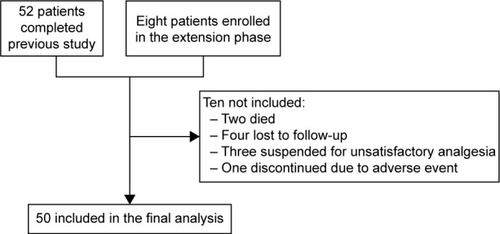

Among the 60 enrolled patients who started the 52-week observation, 50 patients (83.3%) completed the follow-up study. One patient experienced a severe adverse event (drowsiness) leading to OXN-PR discontinuation within the first week. Nine other patients discontinued treatment prematurely: patient disposition is reported in . The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 60 patients are shown in . Their mean age was 81.7 years, and included 36 subjects who were aged >80 years. The PI at baseline was 6.7±1.2, varying between 8.1±0.9 on the move and 5.2±2.2 at nighttime. Unsuccessful analgesics before enrollment were WHO step 1 (46 patients) and WHO step 2 (22 patients). Rescue analgesics were required in 85% of the cases. The overall bowel function was expressed by the mean BFI score (35.9±19.1), and the mean MMSE score (25.7±2.7), Barthel Index score (53.9±13.9), and BPI mean score within the items recorded (6.0±1.6) were also reported.

Table 1 Demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population

Changes in PI at the three scheduled time points for patients who completed the follow-up are reported in . A substantial, statistically significant (P<0.0001), decrease of pain was documented. In a similar way, the PI as a mean of the four measures was significantly reduced.

Table 2 Pain intensity (NRS score) during the 52 weeks of oxycodone/naloxone prolonged-release treatment

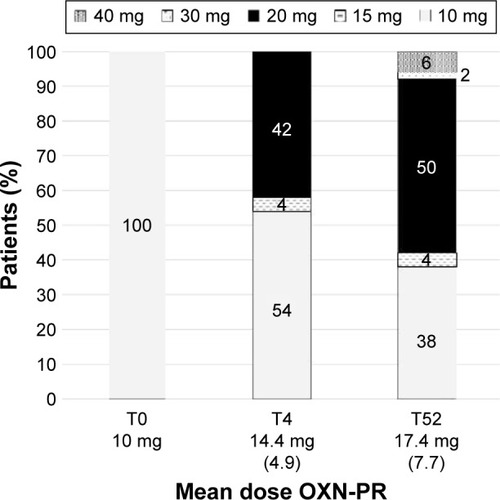

All patients started OXN-PR with a dose of 5/2.5 mg twice a day. During the follow-up, the dose was increased to 20/10 mg in 42% of patients at 4 weeks and to 40/20 mg at 52 weeks in only 6% of patients (). Overall, the mean daily dose of oxycodone increased from 10 mg (T0) to 14.4±4.9 mg (T4) to the final 17.4±7.7 mg (T52) (P<0.0001).

Figure 2 Distribution of OXN-PR daily dosages throughout the observation (expressed in oxycodone equivalents).

The findings of the secondary endpoints are shown in . The MMSE score remained stable during the follow-up; the Barthel Index increased slightly between T0 and T4 (P<0.0001) without further changes up to T52; BPI items improved during the first month of treatment (P<0.0001), remaining at the same level thereafter. The mean SOAPP-R score at 52 weeks was 2.6 (standard deviation 1.6), thus suggesting a low risk of aberrant medication-related behavior in our population.

Figure 3 Value of secondary outcomes (BPI, MMSE, and Barthel Index) at different time points of the observations.

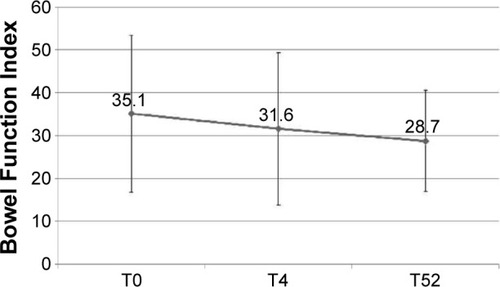

The improvement in pain control was paralleled by a slight improvement in bowel function: mean BFI values decreased from 35.1 at baseline to 28.7 at T52 (P=0.0002) (). An opposite trend was observed with regard to the proportion of patients receiving supplementary laxatives: 38% at T0, 53% at T4, and 29% at T52 (data not shown).

The proportion of the responders according to the primary endpoint, namely, patients who achieved a ≥30% reduction in PI in the absence of a bowel function worsening, was 78% at T4 and 96% at T52 (P<0.0001) (data not shown).

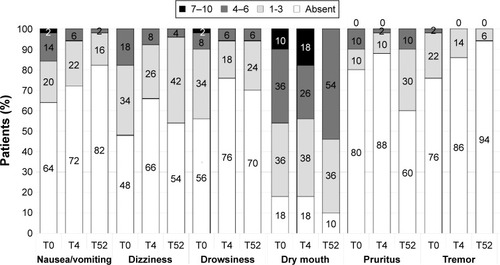

shows the prevalence and severity of commonly observed opioid-related side effects and tremor at different points of the observation. Nausea/vomiting and tremor gradually decreased during the follow-up. Dizziness, drowsiness, and pruritus only slightly decreased during the first 4 weeks and then increased a little up to 52 weeks. Dry mouth worsened slightly over the 52-week observation.

Discussion

Older patients exhibit a high incidence of chronic pain conditions, partially due to age-related alterations of the peripheral somatosensory system and increased activity of the central glial cells.Citation30 Microglia are the primary modulators of pain neurons and their sensitization promotes a persistent condition of neuroinflammation. Aging is associated with impaired endogenous inhibitory systems with dysfunctional changes in pain modulatory capacity.Citation31–Citation34 Due to these changes and the higher frailty of older people, chronic painful and disabling conditions are very common. Moreover, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability is a major determinant of the dose–effect relationship in older patients and should also be considered when choosing the most appropriate analgesic regimen. Available analgesics include nonopioids such as acetaminophen, NSAIDs, cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, and opioids.

Acetaminophen has been recommended by the American Geriatrics Society clinical practice guidelineCitation3 and the American College of RheumatologyCitation35–Citation37 as the first-line agent in the treatment of mild-to-moderate chronic pain, given its moderate toxicity. Nevertheless, it has poor analgesic efficacy in severe pain, which limits its utilization.Citation38 The toxicity, both renal and gastrointestinal, of NSAIDs is increased in older patients.Citation3,Citation39 Their prolonged use may compromise the renal function and increase the risk of cerebrovascular attacks, as well as congestive heart failure in patients with cardiovascular disease by tenfold. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors offer improved gastrointestinal tolerance, but pose similar risk to renal and cardiovascular function.Citation40 Among the opioids, tramadol can be indicated for moderate pain unrelieved by acetaminophen,Citation41 with some limitations due to its low pharmacological potency, the presence of a ceiling effect, and the risk of a serotonergic syndrome. Finally, “strong opioids”,Citation1 commonly used in cancer pain patients and the third step of WHO guidelines, are now increasingly employed for all types of pain including the chronic pain of musculoskeletal disease. Opioids also present some risks of negative effects, specifically possible poor responsiveness, side effects, tolerance, abuse, and addiction. While that does not prevent their use in CNCP, it suggests careful selection of the patients, and a monitoring of some clinical parameters during the treatment is necessary.

A strength and originality of our study consists in the combination of CNCP, geriatric patients (82 years of age on average), and long-term treatment (1 year). The objectives of therapy in this case were relief of pain, improvement of physical daily activity and quality of life in the absence of important side effects, and drug consumption not clinically targeted.

The 50 patients who completed the study achieved an important analgesic effect throughout 1 year of low-dose OXN-PR. The initial PI was halved at T4 and further reduced at T52. It should not be taken for granted that the efficacy was maintained for such an extended time. Opioid therapy often runs into tolerance, whose appearance is easily recognized by the drop of analgesic effect with a simultaneous compensatory dose escalation. In our study, we found no loss of analgesia and only a moderate increase of the daily dose over time (from 10 mg of oxycodone to 17.4±7.7 mg daily on average). This observation is in agreement with the results of other studies based on OXN therapy.Citation42,Citation43 The first of these, Lazzari et al,Citation42 was a comparative study between prolonged-release oxycodone and OXN in opioid-naïve cancer patients with moderate-to-severe pain. Analgesia was achieved and maintained with similarly low and stable dosages over 60 days (from 11.5 to 22.0 mg/day of oxycodone in the OXN group). Trenkwalder et alCitation43 designed a study to evaluate the effects of OXN in the treatment of severe restless legs syndrome; the mean daily dose was 18.1 mg of oxycodone and 9.1 mg of naloxone for a median period of treatment of 281 days.

Stable doses of OXN-PR over time have been repeatedly reported for the treatment of CNCP in opioid-naïve patients, after very low starting doses. Furthermore, the long-term steadiness of the opioid dose is associated with persistent analgesia and a limited number of treatment switches and discontinuations. Further studies providing additional contribution to the strategy of treatment of CNCP are required.

The low dose may also explain the good safety profile observed in our geriatric patients. The prevalence of typically expected adverse opioid reactions was at low levels. Only dry mouth tended to be particularly frequent (82%–90% of patients), which is also likely related to the advanced age.

Nausea and vomiting, on the contrary, were infrequent (28% at T4 and 18% at T52), probably due to the action of naloxone at the gastric level by the same mechanism involved at bowel level. Similar observations have also been made in two previous studies.Citation18,Citation42

Special attention has to be paid to the issue of constipation. In this study, the degree of constipation, measured by BFI, consistently decreased from the initial value of 35.1 to 31.6 (T4) and to the final value of 28.7 at T52. This last value, reached at T52, is deemed as a normal value in patients with chronic pain. Considering the age of patients and the prolonged treatment with opioids, this result can be viewed very positively. In parallel, cognitive functions were unequivocally not affected by long-term treatment with OXN, in contrast to the effects observed in studies that used other opioids.Citation44,Citation45 The daily activity tended to improve over time, and similarly, some quality of life parameters, detected by Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form, particularly referring to moods, enjoyment of life, sleeping, and relations with other people, became significantly better.

Of note and of primary relevance, our results confirm the low risk of addiction in older adults without a history of drug abuse, as confirmed by SOAPP-R assessment in the whole population study. An exceedingly low value was found at T52, well below the cutoff score of 18 traditionally used to identify subjects at increased risk of opioid abuse and misuse.

We utilized a composite endpoint as the primary endpoint. Combining efficacy and tolerability parameters (specifically, the proportion of patients with at least 30% reduction in PI, in the absence of a bowel function worsening), we focused on the two main goals of an effective opioid treatment for chronic pain. The proportion of responders was equivalent to 78% at T4 and 96% at T52, which can be considered an excellent outcome.

This study has several limitations related to the methodology used, specifically the observational design and the absence of a control group. Despite this, the 1-year follow-up and generalizability of the findings are its important strengths.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that low doses of OXN-PR are a valid treatment for chronic moderate-to-severe pain in older patients. During 1 year of treatment, they achieved effective analgesia accompanied by few side effects, improvement of bowel function, and a good level of functional state and quality of life.

Data from the present open-label study confirm that in the older patients, a slow titration of opioids is mandatory to avoid adverse events; the rule “start slowly, go slowly” should always be considered when prescribing opioids to this fragile population.

Despite the aforementioned limitations of the present study, our findings suggest that OXN-PR should be considered as a potentially safe approach for managing painCitation7 and preventing opioid-induced constipationCitation45 in older adults over the long term because of its particular pharmacological profile.

Further studies in older persons with CNCP, looking at the therapeutic approach and safety of OXN-PR will be of great relevance in a phase of critical evaluation of the long-term treatment of pain.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed in developing the concepts, designing the structure, and writing/revising the manuscript, and approved the final version before submission and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The study was completed independently with no funding. We thank Ray Hill, an independent medical writer, who helped with English-language editing and journal styling prior to submission, on behalf of Health Publishing and Services Srl. This assistance was funded by Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals Srl, Milano, Italy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationCancer Pain Relief2nd edGenevaWorld Health Organization1996

- NobleMTreadwellJRTregearSJLong-term opioid management for chronic noncancer painCochrane Database Syst Rev20101CD00660520091598

- American Geriatrics Society Panel on Chronic Pain in Older PersonsThe management of chronic pain in older persons: AGS Panel on chronic pain in older personsJ Am Geriatr Soc19984656356519588381

- AbdullaAAdamsNBoneMGuidance on the management of pain in older peopleAge Ageing201342Suppl 1i1i5723420266

- American Geriatrics Society Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older PersonsPharmacological management of persistent pain in older personsJ Am Geriatr Soc20095781331134619573219

- BlagdenMHaferJDuerrHHoppMBosseBLong-term evaluation of combined prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic pain: pooled analysis of extension phases of two Phase III trialsNeurogastroenterol Motil201426121792180125346155

- KahanMSrivastavaAWilsonLMailis-GagnonAMidmerDOpioids for managing chronic non-malignant pain: safe and effective prescribingCan Fam Physician20065291091109617279219

- PortenoyRKFarrarJTBackonjaMMLong-term use of controlled-release oxycodone for noncancer pain: results of a 3-year registry studyClin J Pain200723428729917449988

- Sandner-KieslingALeyendeckerPHoppMLong-term efficacy and safety of combined prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone in the management of non-cancer chronic painInt J Clin Pract201064676377420370845

- SchulerMGrießingerNOpiode bei nichttumorsch merz im hoheren [Opioids for noncancer pain in the elderly]Schmerz2015294380401 German26264898

- TrescotAMHelmSHansenHOpioids in the management of chronic non-cancer pain: an update of American Society of the Interventional Pain Physicians’ (ASIPP) GuidelinesPain Physician2008112 SupplS5S6218443640

- DavisMPSrivastavaMDemographics, assessment and management of pain in the elderlyDrugs Aging2003201235712513114

- Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals LimitedTargin 5/2.5 mg, 10 mg/5 mg, 20 mg/10 mg and 40/20 mg prolonged release tablets: Summary of Product Characteristics2013 Available from: http://www.medicines.ie/medicine/14383/SPC/Targin+10mg+5mg+and+20mg+10mg+prolonged+release+tabletsAccessed September 15, 2015

- BurnessCBKeatingGMOxycodone/naloxone prolonged-release: a review of its use in the management of chronic pain while counteracting opioid-induced constipationDrugs201474335337524452879

- AhmedzaiSHNauckFBar-SelaGBosseBLeyendeckerPHoppMA randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, double-dummy, parallel-group study to determine the safety and efficacy of oxycodone/naloxone prolonged-release tablets in patients with moderate/severe, chronic cancer painPalliat Med2012261506021937568

- VondrackovaDLeyendeckerPMeissnerWAnalgesic efficacy and safety of oxycodone in combination with naloxone as prolonged release tablets in patients with moderate to severe chronic painJ Pain20089121144115418708300

- AhmedzaiSHLeppertWJaneckiMLong-term safety and efficacy of oxycodone/naloxone prolonged-release tablets in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic cancer painSupport Care Cancer201523382383025218610

- CuomoARussoGEspositoGForteCAConnolaMMarcassaCEfficacy and gastrointestinal tolerability of oral oxycodone/naloxone combination for chronic pain in outpatients with cancer: an observational studyAm J Hosp Palliat Care201431886787624249829

- SchutterUGrunertSMeyerCSchmidtTNolteTInnovative pain therapy with a fixed combination of prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone: a large observational study under conditions of daily practiceCurr Med Res Opin20102661377138720380506

- LowensteinOLeyendeckerPHoppMCombined prolonged-release oxycodone and naloxone improves bowel function in patients receiving opioids for moderate-to-severe non-malignant chronic pain: a randomised controlled trialExpert Opin Pharmacother200910453154319243306

- GuerrieroFSgarlataCMarcassaCRicevutiGRolloneMEfficacy and tolerability of low-dose oral prolonged-release oxycodone/naloxone for chronic nononcological pain in older patientsClin Interv Aging20151011125565782

- MagniEBinettiGBianchettiARozziniRTrabucchiMMini-Mental State Examination: a normative study in Italian elderly populationEur J Neurol19963319820221284770

- RentzAMYuRMuller-LissnerSLeyendeckerPValidation of the Bowel Function Index to detect clinically meaningful changes in opioid-induced constipationJ Med Econ200912437138319912069

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- MahoneyFIBarthelDWFunctional evaluation: the Barthel indexMd State Med J196514616514258950

- BonezziCNavaABarbieriMValidazione della versione Italiana del Brief Pain Inventory nei pazienti con dolore cronico [Validation of Italian version Brief Pain Inventory in patients with chronic pain]Minerva Anestesiol2002687–8607611 Italian12244292

- CleelandCSRyanKMPain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain InventoryAnn Acad Med Singapore19942321291388080219

- ButlerSFBudmanSHFernandezKCFanciulloGJJamisonRNCross-validation of a screener to predict opioid misuse in chronic pain patients (SOAPP-R)J Addict Med200932667320161199

- FarrarJTPortenoyRKBerlinJAKinmanJLStromBLDefining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measuresPain200088328729411068116

- SkaperSDGiustiPFacciLMicroglia and mast cells: two tracks on the road to neuroinflammationFASEB J20122683103311722516295

- EdwardsRRFillingimRBNessTJAge-related differences in endogenous pain modulation: a comparison of diffuse noxious inhibitory controls in healthy older and younger adultsPain20031011–215516512507710

- NaugleKMCruz-AlmeidaYFillingimRBRileyJL3rdOffset analgesia is reduced in older adultsPain2013154112381238723872117

- RileyJL3rdKingCDWongFFillingimRBMauderliAPLack of endogenous modulation and reduced decay of prolonged heat pain in older adultsPain2010150115316020546997

- WashingtonLLGibsonSJHelmeRDAge-related differences in the endogenous analgesic response to repeated cold water immersion in human volunteersPain2000891899611113297

- American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis GuidelinesRecommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 updateArthritis Rheum20004391905191511014340

- HochbergMCAltmanRDBrandtKDGuidelines for the medical management of osteoarthritis. Part I. Osteoarthritis of the hip. American College of RheumatologyArthritis Rheum19953811153515407488272

- SchnitzerTJAmerican College of RheumatologyUpdate of ACR guidelines for osteoarthritis: role of the coxibsJ Pain Symptom Manage2002234 SupplS24S30 discussion S31–S3411992747

- MachadoGCMaherCGFerreiraPHEfficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trialsBMJ2015350h122525828856

- SinghGRecent considerations in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathyAm J Med19981051B31S38S9715832

- TrelleSReichenbachSWandelSCardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysisBMJ2011342c708621224324

- SchnitzerTJManaging chronic pain with tramadol in elderly patientsClin Geriatr199973545

- LazzariMGrecoMTMarcassaCFinocchiSCaldaruloCCorliOEfficacy and tolerability of oral oxycodone and oxycodone/naloxone combination in opioid-naive cancer patients: a propensity analysisDrug Des Devel Ther2015958635872

- TrenkwalderCBenesHGroteLProlonged release oxycodone-naloxone for treatment of severe restless legs syndrome after failure of previous treatment: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with an open-label extensionLancet Neurol201312121141115024140442

- LandroNIForsEAVapenstadLLHoltheOStilesTCBorchgrevinkPCThe extent of neurocognitive dysfunction in a multidisciplinary pain centre population. Is there a relation between reported and tested neuropsychological functioning?Pain2013154797297723473784

- SchiltenwolfMAkbarMHugAEvidence of specific cognitive deficits in patients with chronic low back pain under long-term substitution treatment of opioidsPain Physician201417192024452649