Abstract

Objective

Hemangiomas are the most common benign vascular tumors of infancy. Although most infantile hemangiomas (IHs) have the ability to involute spontaneously after initial proliferation and resolve without consequence, intervention is required in a subset of IHs, which develop complications resulting in ulceration, bleeding, or aesthetic deformity. The primary treatment for this subset of IHs is pharmacological intervention, and propranolol has become the new first-line treatment for complicated hemangiomas. Here, we evaluated the efficacy of propranolol on proliferation IH in a clinical cohort including 578 patients.

Methods

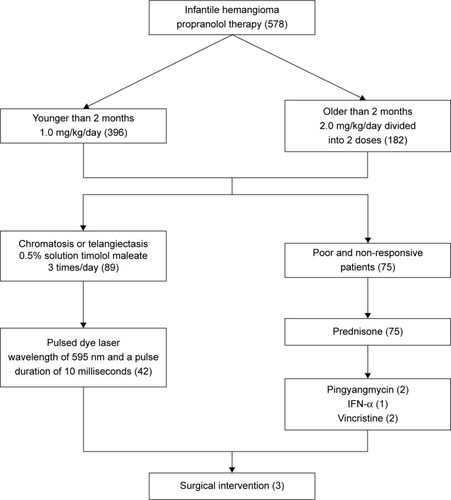

We retrospectively reviewed a total of 578 IH patients who were treated with oral propranolol from January 2010 to December 2012. Responses to the propranolol treatment were graded as: excellent, good, poor, or no response. Based on the response to propranolol treatment (once daily at a dose of 1.0 mg/kg for patients younger than 2 months; twice daily at daily total dose of 2 mg/kg for patients older than 2 months), additional pharmacotherapies or surgery were used for IH patients for satisfactory clinical outcome.

Results

Five hundred and sixty (96.9%) of 578 IH patients in our study responded to oral propranolol treatment, and the response rate was significantly different for different ages of patients (P<0.05), with the youngest patients having the highest response rate. The mean time of treatment was 6 months (range, 3–12 months). For example, response rate to propranolol was 98.1% in patients younger than 2 months, compared with 93.3% in patients older than 2 months and younger than 8 months, and 73.7% in patients older than 8 months. One hundred and thirty one patients who exhibited incompletely involuted hemangiomas were further treated with timolol maleate (n=89) or pulsed dye laser (n=42). One hundred and seventeen (89.3%) of 131 patients showed a positive response. There were no instances of life-threatening complications after propranolol. However, minor side effects were observed including 10 (1.73%) cases of sleep disturbance, 7 (1.21%) cases of diarrhea, and 5 (0.86%) cases of bronchospasm.

Conclusion

IH requires early intervention. During the involution phase, tapering propranolol dosage can be done to minimize side effects before discontinuing treatment. For patients exhibiting telangiectasia and chromatosis after propranolol treatment, administration of a 0.5% solution of timolol maleate or pulse dye laser is an effective therapeutic approach for complete involution.

Introduction

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are the most common benign tumor in pediatric patients, and 60% of IHs occur on the head and neck.Citation1 The natural history of IH is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase during early infancy, from birth to approximately 1 year of age, followed by a gradual involution that may last until the age of 10 years.Citation2 Previous treatment of IH commonly involved implementing a “watch-and-wait” strategy. However, a subset of IHs cannot involute spontaneously and this may lead to unpredictable outcome, including serious complications and cosmetic disfigurement, causing functional and psychological effects on parents and the affected children.Citation3 Therefore, there is an urgent need for prompt recognition and treatment for this IH subset.Citation4 Traditional therapy for IH includes long-term and high-dose usage of steroids, which has been reported to be associated with multiple side effects.Citation5 In 2008, Léauté-Labrèze et alCitation6 found propranolol as a treatment for severe hemangiomas of infancy by accident. The β-blocker has become the new first-line treatment for complicated hemangiomas.Citation6 However, the efficacy of propranolol in treating IH patients is not universal. For patients resistant to propranolol therapy, there are other options including oral administration of prednisone and intraregional injections of pingyangmycin, interferon α (IFN-α), or vincristine.Citation7–Citation10 These treatments all have potentially severe side effects. Topical use of timolol in IH patients can help avoid side effects of propranolol treatment.Citation11 Further studies are required to improve the efficacy and reduce side effects of current IH therapies. In this study, we describe the results of treating IH patients with propranolol only or propranolol followed by prednisone, timolol, or pulsed dye laser, which contributes to the practice guideline for the treatment of patients with IH.

Methods

Patients

This study enrolled 578 patients undergoing treatment for IH at the Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, People’s Republic of China, from January 2010 to December 2012. The human subject protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ninth People’s Hospital (IRB:201548). Patients were diagnosed with proliferating IH by the Department of Oral-Maxillary Head and Neck at the Ninth People’s Hospital Shanghai and written informed consents were obtained from the parents or guardians including images to be published for this study in accordance with The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. A standardized database recorded patient details, which included patient gender, age at treatment initiation, location and size of the lesion, medication and dose, clinical response, and complications resulting from treatment and follow-up.

Propranolol treatment

Prior to propranolol treatment, a color sonography was performed to detect any possible congenital cardiac disturbances such as atrioventricular block or bradycardia etc. For propranolol treatment, patients were treated on an outpatient basis, and the mean time of treatment was 6 months. To minimize complications, oral propranolol was administered once daily at a dose of 1.0 mg/kg for patients younger than 2 months, while it was administered twice daily at daily total dose of 2 mg/kg for patients older than 2 months. In the last month of treatment, the propranolol dose was halved for the first 2 weeks. If no rebound occurred, the dose was further halved for the following 2 weeks before propranolol treatment was discontinued completely. Patient body weight was measured every 2 weeks and propranolol dosage was adjusted according to the change of body weight.

Advanced treatments

For patients with small tumor reduction after treatment with propranolol for 2 weeks, oral prednisone was administered at a dose of 5 mg every 2 days.

For patients with complicated hemangiomas and those nonresponsive to propranolol or prednisone treatment, pingyangmycin, IFN-α, or vincristine treatments were applied. These three medicines were used only in the second or third line owing to the potential side effects. For pingyangmycin treatment, patients were intralesionally injected a daily dose of 1 mg for 2.5 months. For IFN-α treatment, patients were subcutaneously injected a daily dose of 3×106 Unit/m2 for 3 months. For vincristine treatment, patients were intravenously administered a dose of 1.0 mg/m2 every 2 weeks with an interval of 1 week between rounds and a total of 2 rounds.

For patients with chromatosis or telangiectasia after propranolol treatment, a 0.5% solution of timolol maleate was applied topically over the lesion surface using a cotton swab 3 times daily. If no response was observed after 2 weeks of treatment with timolol maleate, high-frequency pulsed dye laser was applied using a wavelength of 595 nm and a pulse duration of 10 ms.

Therapy evaluation

Photographs were taken and ultrasound examinations were done to evaluate therapy efficacy. Ultrasound examination can measure the width and the height of IH lesions. Volume = width × height2/2.Citation12 Both photographs and ultrasound examinations were performed prior to treatment, at 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months following treatment as well as at each follow-up visit. Photographs can enable direct visualization of volume change, and ultrasound examinations can provide the quantitative data. Responses to propranolol were graded as follows: a tumor reduction greater than 75% was considered an “excellent” response; a reduction greater than 50% a “good” response; a reduction of 25% or less a “poor” response; and a 0% reduction was considered “nonresponsive.”

Statistical analysis

Response rate (RR) to propranolol was summarized according to patient demographic or disease characteristics using analysis of paired t-test, with P<0.05 considered significant. Software SPSS (Version 19.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis.

Results

Patient demographic and disease characteristics

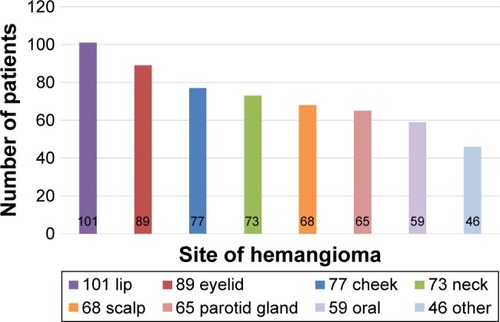

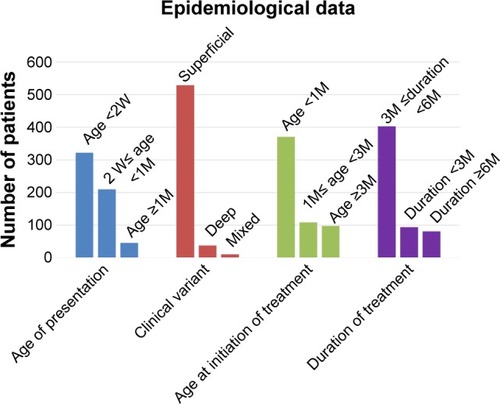

This study was conducted in a cohort of 578 patients with mean age of 6.12±5.29 months (range, 1–12 months). The overall male-to-female ratio was 1:4.7. Ninety seven (16.8%) of 578 patients were premature, and progesterone was the most common tocolytic agent used for the treatment of mothers during the gestational period. The most common anatomic sites in this study were lips (17.5%) and the eyelids (15.4%) (). The mean size of hemangioma was 20.26±19.57 cm2. Five hundred and twenty nine (91.5%) hemangiomas were superficial hemangiomas, 38 (6.6%) were subcutaneous hemangiomas, and 11 (1.7%) were mixed hemangiomas.

Patient response to propranolol treatment

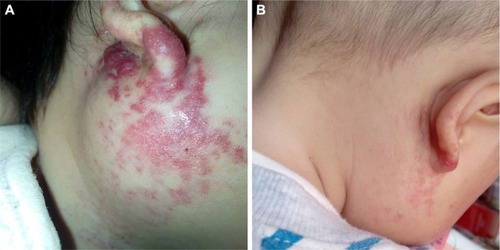

Our results revealed significant differences in RR for different ages of patients, with the youngest patients having the highest RR (P<0.05, t-test). RR to propranolol in the group younger than 2 months was 98.1% (), compared with 93.3% in patients older than 2 months and younger than 8 months ( and ), and 73.7% in patients older than 8 months (). The difference was not related to gender. In addition, as for the tumor location, RR was highest when tumors were located in the parotid region and lowest in the lip region (RR: 97.8%, 85.1%, P<0.05, t-test). However, RR to propranolol was not significant for different types of IH (superficial, subcutaneous, or mixed hemangiomas RR: 94.5%, 91.7% vs 87.3%, P<0.05, t-test). Moreover, RR to propranolol was further characterized as follows: 186 (32.2%) of 578 patients exhibited excellent response; 317 (54.8%) exhibited good response; 57 (9.9%) exhibited poor response; and 18 (3.1%) were nonresponsive. The mean time of treatment was 6 months (range, 3–12 months) ().

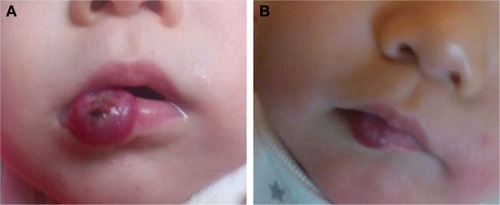

Figure 2 (A) A 2-month-old female patient had a large hemangioma located on her right lower lip which showed ulceration on its surface. (B) The hemangioma on the same patient significantly improved after 5-month treatment of oral propranolol.

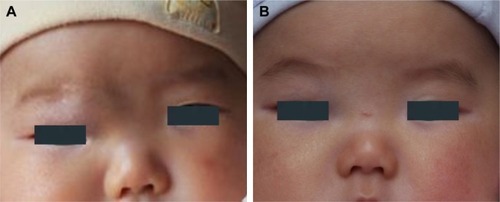

Figure 3 (A) A 3-month-old female patient with a hemangioma located on her right endocanthion. (B) The same patient with the treatment of oral propranolol for 3 months exhibited involuted hemangioma.

Figure 4 (A) An 8-month-old female patient with a hemangioma located on her right leg. (B) The hemangioma on the same patient involuted after 4-months treatment of oral propranolol.

Patient response to advanced treatments

For patients with poor response or those who were non-responsive to propranolol (75 patients), oral prednisone was added to the treatment regimen. After treatment with prednisone, lesions in 67 (89.3%) of 75 patients involuted without rebound. As for the remaining 8 nonresponsive patients, advanced treatments were administered including pingyangmycin (2 patients), IFN-α (1 patient), vincristine (2 patients), or surgical intervention (3 patients). No rebound was observed in these 8 cases, and patients all showed satisfactory results to advanced treatments.

After propranolol treatment, 131 patients exhibited incompletely involuted hemangiomas (chromatosis or telangiectasia) and were further treated with timolol maleate (89 patients) () or pulsed dye laser (42 patients). One hundred and seventeen (89.3%) of 131 patients showed positive response.

Figure 7 (A) A 6-month-old male patient with a hemangioma located on his nasion and forehead. (B) After 6-month treatment of oral propranolol, the same patient exhibited involuted hemangioma with telangiectasia and chromatosis remaining on his nasion and forehead. (C) The telangiectasia and chromatosis on the same patient improved significantly after treatment with a 0.5% solution of timolol maleate for 8 weeks. Two drops of 0.5% timolol maleate solution was applied onto the surface of the hemangioma three times daily. (D) The telangiectasia and chromatosis were involuted completely after 24 months.

Overall, no patients in our study developed life- threatening complications; 23 (3.98%) of 578 patients developed minor complications including sleep disturbance (10 patients), diarrhea (7 patients), and bronchospasm (5 patients). The mean duration of follow-up was 3.08±0.83 years (– and ). For patients with excellent (186 patients) or good propranolol response (317 patients), rebounds of IHs were only detected in 6 (1.2%) of 503 patients, which faded away with additional propranolol treatment for no more than 3 months.

Discussion

Currently, there is no way to predict the outcome of proliferative IH.Citation13 A subset of IH can potentially be associated with psychological trauma of infants and anxiety of parents, which requires early intervention, thus calling for the reevaluation of traditional “watch and wait” approaches for IH treatment.Citation14 So far, different modalities have been reported for the treatment of IHs, including surgery (laser surgery and cryosurgery) and pharmacotherapy (β-blocker, corticosteroids, INF-α, and vincristine). As a β-blocker, propranolol has been proven to be very effective and safe for IH therapy, which dramatically changes IH therapeutic strategy and makes propranolol replace corticosteroids as the first-line treatment for IH.Citation15

Although no standard regimen for IHs has been established, treatment of IH should be taken carefully and instituted with rigorous guidelines. In previous studies, we treated IH patients with oral propranolol as inpatients for 48 hours and closely monitored their blood pressure and heart rates. No obvious changes were observed. In this study, IH patients were treated with oral propranolol in an outpatient setting. The dose was not unique because the potential side effects were not clear. So we initiated propranolol therapy at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg/d, and then tapered propranolol over a 1-month period to minimize the risk of withdrawal response. In addition, oral propranolol was administered after food to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia. The remarkable efficacy of propranolol for the treatment of IH was observed not only in the rapid growth phase but also in the following involution phase.Citation16 Therefore, the duration of propranolol treatment for IH patients is also very important for clinical outcome. In this study, the duration of propranolol therapy lasted an average of 6 months, and treatment was terminated when the infants reached 1 year of age.Citation17

The efficacy of propranolol on our IH patient cohort was encouraging, with good RR, few rebounds, and limited side effects. All IH patients receiving advanced treatment exhibited satisfactory outcome.Citation18 For patients with excellent or good response to propranolol, 131 (26%) exhibited telangiectasia and chromatosis after treatment and were further treated with a 0.5% solution of timolol maleate or pulsed dye laser for complete involution.Citation19 Timolol is a β-blocker and commonly used to treat nasal telangiectasia and epistaxis.Citation20 Timolol also plays a critical role in the treatment of superficial IH.Citation21 Compared with systemic oral propranolol treatment, topical timolol treatment is nonsystemic and associated with less side effects.Citation22–Citation24

Despite the success of propranolol in IH treatment, the underlying mechanism of propranolol treatment remains elusive. A previous study demonstrated that propranolol targets hemangioma stem cells via cAMP and mitogen-activated protein kinase regulation.Citation25 In this study, we found that RR to propranolol was significantly higher in younger patients, with patients younger than 2 months having the highest RR, which is in line with previous findings. We think estrogen is the critical factor. In our basic research, at the same time, we found that estrogen promoted angiogenesis via combined with ERα to upregulating the expression of VEGF-A in hemangioma derived stem cell, promoting proliferation of IHs. Propranolol inhibits angiogenesis via downregulating the expression of VEGF in hemangioma-derived stem cells.Citation26 In this study when the patient was younger, the activity was stronger. So, a better result was achieved when the patients were younger than 2 months. However, further studies are required to better clarify the mechanism of propranolol in IH treatment.

Conclusion

Early intervention is critical in treating IH. Treatment of IH with propranolol in this study demonstrated high efficacy and tolerance with few adverse effects. For patients with telangiectasia and chromatosis after propranolol treatment, administration of a 0.5% solution of timolol maleate or pulsed dye laser led to adequate involution. In cases with poor response or those who were nonresponsive to propranolol, additional surgeries or pharmacotherapies using prednisone, IFN-α, or vincristine can achieve satisfactory results. In summary, our study reported a successful treatment of IH using first-line treatment, advanced treatment, reevaluation, and modification of treatment according to patient response ().

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81541041) and (81570992) and the Fund for Interdisciplinary Projects of Medicine and Engineering by Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2015MS06).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Notes

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- FinnMCGlowackiJMullikenJBCongenital vascular lesions: clinical application of a new classificationJ Pediatr Surg198318 894 9006663421

- MarlerJJMullikenJBCurrent management of hemangiomas and vascular malformationsClin Plast Surg200532 99 11615636768

- TalaatAAElbasiounyMSElgendyDSElwakilTFPropranolol treatment of infantile hemangioma: clinical and radiologic evaluationsJ Pediatr Surg201247 707 71422498385

- MullikenJBGlowachiJHaemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristicsPlast Reconstr Surg198369 412 422

- FawcettSLGrantIHallPNKelsallAWRNicholsonJCVincristine as a treatment for a large haemangioma threatening vital functionsBr Assoc Plast Surg200457 168 171

- Léauté-LabrèzeCDumas de la RoqueEHubicheTBoraleviFThamboJBTaïebAPropranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancyN Engl J Med2008358 2649 265118550886

- HouJWangMTangHWangYHuangHPingyangmycin sclerotherapy for infantile hemangiomas in oral and maxillofacial regions: an evaluation of 66 consecutive patientsInt J Oral Maxillofac Surg201140 1246 125121893396

- EnjolrasORicheMCMerlandJJEscandeJPManagement of alarming hemangiomas in infancy: a review of 25 casesPediatrics199085 491 4982097998

- EzekowitzRAMullikenJBFolkmanJInterferon alfa-2a therapy for life-threatening hemangiomas of infancyN Engl J Med1992326 1456 14631489383

- FuchimotoYMorikawaNKurodaTVincristine, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide chemotherapy resolves Kasabach-Merritt syndrome resistant to conventional therapiesPediatr Int2012542 285 28722507155

- GuoSNiNTopical treatment for capillary hemangioma of the eyelid using beta blocker solutionArch Ophthalmol2010128 255 25620142555

- OrtaldoJRPorterHRMillerPStevensonHCOzolsRFHamiltonTCAdoptive cellular immunotherapy of human ovarian carcinoma xenografts in nude miceCancer Res198646 4414 44193089592

- WernerJADunneAAFolzBJCurrent concepts in the classification, diagnosis and treatment of hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the head and neckEur Arch Otorhinolaryngol2001258 141 14911374256

- KushnerBJHemangiomasArch Ophthalmol2000118 835 83610877753

- Léauté-LabrèzeCVoisardJJMooreNOral propranolol for infantile hemangiomaN Engl J Med201516 284 285

- ChenTSEichenfieldLFFriedlanderSFInfantile hemangiomas: an update on pathogenesis and therapyPediatrics2013131 99 10823266916

- ZhengJWYangXJWangYAHeYYeWMZhangZYIntralesional injection of Pingyangmycin for vascular malformations in oral and maxillofacial regions: an evaluation of 297 consecutive patientsOral Oncol200945 872 87619628423

- WangZLiKYaoWSteroid-resistant kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a retrospective study of 37 patients treated with vincristine and long-term follow-upPediatr Blood Cancer2015624 577 58025346262

- MooreAPinkertonRVincristine: can its therapeutic index be enhanced?Pediatr Blood Cancer200953 1180 118719588521

- Sommers SmithSKSmithDMBeta blockade induces apoptosis in cultured capillary endothelial cellsIn Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim200238 298 30412418927

- PopeEChakkittakandiyilATopical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: a pilot studyArch Dermatol2010146 564 56520479314

- GeJZhengJZhangLOral propranolol combined with topical timolol for compound infantile hemangiomas: a retrospective studySci Rep20166 1976526819072

- ZhangLYuanWZhengJPharmacological therapies for infantile hemangiomas: A clinical study in 853 consecutive patients using a standard treatment algorithmSci Rep20166 2167026876800

- ChenZZhengJYuanMA novel topical nano-propranolol for treatment of infantile hemangiomasNanomedicine: NBM2015115 1109 1115

- MunabiNCEnglandRWEdwardsAKPropranolol targets hemangioma stem cells via cAMP and mitogen-activated protein kinase regulationStem Cells Transl Med20165 45 5526574555

- ZhangLMaiHMJingZhengPropranolol inhibits angiogenesis via down-regulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in hemangioma derived stem cellInt J Clin Exp Pathol20147 48 5524427325