Abstract

Giant cell arteritis is the most common vasculitis in Caucasians. Acute visual loss in one or both eyes is by far the most feared and irreversible complication of giant cell arteritis. This article reviews recent guidelines on early recognition of systemic, cranial, and ophthalmic manifestations, and current management and diagnostic strategies and advances in imaging. We share our experience of the fast track pathway and imaging in associated disorders, such as large-vessel vasculitis.

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis is a vasculitis of large-sized and medium-sized vessels causing critical ischemia. It is linked with polymyalgia rheumatica, which is characterized by abrupt-onset pain and stiffness of the shoulder and pelvic girdle muscles. Both conditions occur in the elderly and are associated with constitutional symptoms and a systemic inflammatory response.

Giant cell arteritis is a medical emergency, with permanent visual loss occurring in about 20% of patients.Citation1 There is a need for urgent recognition and immediate initiation of high-dose oral or parenteral steroids to prevent visual loss and other ischemic complications. Patients with ischemic symptoms, such as diplopia, transient visual loss, or jaw/tongue claudication, are at particularly high risk. Elderly patients with sight loss otherwise face poor outcomes, with increased mortality, loss of independence, severe depression, complications such as hip fractures, and admission to residential homes. There may also be poor outcomes related to high-dose prolonged glucocorticoid-related adverse events, such as diabetes, fractures, and cardiovascular complications. Glucocorticoids remain the mainstay of therapy, but disease-modifying conventional agents, such as methotrexate and leflunomide, as well as biological therapy, eg, tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 blocker, have an increasing role in relapsing disease.

This article updates on giant cell arteritis and the related conditions of polymyalgia rheumatica and large-vessel vasculitis; reviews recent guidelines on early recognition of systemic, cranial, and ophthalmic manifestations; current management and diagnostic strategies and advances in imaging, including temporal artery ultrasound, fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Pathology

Despite recent advances in molecular medicine and immunology, the initial events triggering the cascade of immune and inflammatory reactions responsible for giant cell arteritis remain unclear. The initiating step may be the recognition of an infectious agent by activated dendritic cells. The key cell type involved is the CD4+ T cell and the key cytokines are interferon-gamma (implicated in granuloma formation) and interleukin-6, which are key to the systemic response.Citation2 The pathogenesis of polymyalgia rheumatica may be similar to that of giant cell arteritis, but in general, polymyalgia rheumatica exhibits less clinical vascular involvement. However, aortic and large vessel involvement is now appreciated in both polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis not adequately responding to glucocorticoids.

Epidemiology

Giant cell arteritis with polymyalgia rheumatica is predominantly seen in the elderly, with cases under the age of 50 years being rare and the incidence increasing with advancing age.Citation3,Citation4 It is more common in females, with a 2.5–3.0-fold relative risk,Citation5 and also commoner in Caucasians, particularly in those of Scandinavian descent, but less common in other ethnic groups. The incidence in Olmsted County, MN, is estimated in those over 50 years of age at 18.8 per 100,000 population.Citation6 Polymyalgia rheumatica is 2–3 times more common than giant cell arteritis. The incidence is lower in Southern European countries (<12/1,000,000 in those aged 50 years and older).Citation7 A study in the UK showed that the age-adjusted incidence rate of giant cell arteritis was 2.2 per 10,000 person years.Citation8 There is some geographic and racial variation. Among Asian populations, giant cell arteritis is infrequent, with Takayasu’s arteritis being the more frequently seen large-vessel vasculitis.

Ophthalmic manifestations of giant cell arteritis

Visual loss

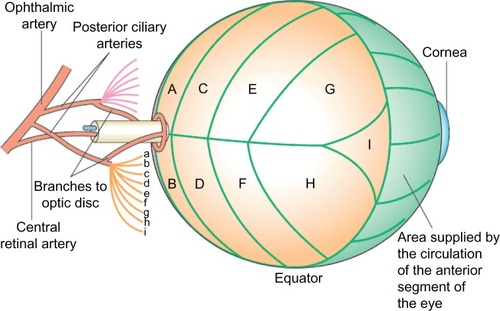

Acute visual loss in one or both eyes is by far the most feared and irreversible complication of giant cell arteritis. The main blood supply compromised by giant cell arteritis is to the anterior optic nerve head via the short posterior ciliary arteries and that of the retina via the central retinal artery. There is also choroidal ischemia in giant cell arteritis because short posterior ciliary arteries also supply this region ().

Figure 1 Schematic representation of posterior retinal circulation. Parts of the blood supply to the optic disk, and the segmentation of the choroidal circulation are illustrated. The short posterior ciliary arteries (a–i) supply segments of the choroid (A–I) posterior to the equator of the globe.

©2006 Nature Publishing Group. Reproduced with permission from Aristodemou P, Stanford M. Therapy insight: the recognition and treatment of retinal manifestations of systemic vasculitis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2(8):443–451.Citation23

In a Swiss study of 85 patients with giant cell arteritis (including 78% biopsy-positive cases) the authors reported that 62 (73%) presented with ischemic events which included jaw claudication, blurred vision, amaurosis fugax, permanent vision loss, and ischemic stroke. In this study, 29 of 85 patients (34%) had permanent vision loss or stroke.Citation9

A retrospective Spanish study of 161 patients with biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis found that 42 patients (26%) had visual manifestations of their disease, and of these patients, 24 (14.9%) developed permanent visual loss (9.9% unilateral, 5% bilateral).Citation10 Moreover, 7.5% of the patients experienced amaurosis fugax and 5.6% had diplopia before developing permanent loss of vision. Permanent visual loss was caused by anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in 91.7% and central retinal artery occlusion in 8.3%, and one patient had a vertebrobasilar stroke causing cortical visual loss.

An Italian study reported visual symptoms in 30.1% of their subjects, with partial or total visual loss in 19.1%.Citation11 Of the 26 cases with visual loss, 92.3% were due to anterior ischemic optic neuritis and 7.7% had central retinal artery occlusion. Visual loss was unilateral in 73.1% and bilateral in 26.9%. Furthermore, 25 of the 26 patients developed visual loss before corticosteroid therapy was started. However, visual manifestations may arise at any point in the natural course of the disease. If untreated, the other eye is likely to become affected within 1–2 weeks. Once established, visual impairment is usually permanent.

In a recent report by Ezeonyegi et al of 65 patients with giant cell arteritis, 23 patients had visual disturbance at presentation (35.3%).Citation12 Visual loss at presentation occurred in 16 patients (24.6%). Over 5 years, 19 patients were left with permanent visual impairment, eight of whom had bilateral loss of vision. Five patients had cerebrovascular complications, the majority of these being transient ischemic attacks. One developed bilateral occipital infarcts with cortical blindness, and another developed oculomotor palsy. Ten patients (15.4%) presented with neuro-ophthalmic complications in the absence of headache, seven (70%) of whom developed permanent visual impairment. Five (7.7%) patients had cerebrovascular complications. A significant minority of cases without headaches presented with constitutional, polymyalgic, and ischemic symptoms.

Ophthalmology studies report occult giant cell arteritis where visual loss is the presenting symptom. In a study of 85 patients, 21.2% of the patients with visual loss and positive temporal artery biopsy for giant cell arteritis were reported not to have associated systemic symptoms.Citation13 Patients may present with transient visual loss, which is generally unilateral.Citation13 However, this may relate to lack of awareness of non-headache presentations, as described above, and underlines the crucial importance of recognizing constitutional and polymyalgic features to reduce delayed recognition and giant cell arteritis diagnosis only after onset of permanent sight loss.

Predictors of visual loss and delay in recognition: “symptom to steroid time”

Features predictive of permanent visual loss include history of amaurosis fugax, jaw claudication, and temporal artery abnormalities on physical examination.Citation14 Amaurosis fugax is an important visual symptom because it precedes permanent visual loss in 44% of patients. Delay in recognition may be the most important factor, given that the mean time from symptom onset to diagnosis of giant cell arteritis was 35 days in the study by Ezeonyeji et al, and recognition of ischemic symptoms was slow.Citation12 Mackie et al found that socioeconomic deprivation may be associated with ischemic complications,Citation15 again suggesting that lack of awareness and delay in recognition may be contributory factors.

Diplopia

Transient or constant diplopia is a frequent visual symptom related to giant cell arteritis. The reported incidence of diplopia in two large studies is approximately 6%.Citation10,Citation16 Ophthalmoplegia in giant cell arteritis is commonly associated with difficulty in upward gaze.Citation17 Partial or complete IIIrd or VIth nerve palsy can be revealed on examination. The exact etiology of ophthalmoplegia in giant cell arteritis is not known. Ischemia to the extraocular muscles, the cranial nerves, or brain stem ocular motor pathways have all been postulated as the mechanism of diplopia in giant cell arteritis.Citation18

Unusual ocular manifestations

Rare ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis include tonic pupil,Citation19 Horner syndrome,Citation20 and internuclear ophthalmoplegia.Citation21 Visual hallucinations seen in patients with cortical blindness are secondary to occipital infarction. Ocular ischemic syndrome is another uncommon manifestation of giant cell arteritis. It is a result of acute inflammatory thrombosis of multiple ciliary arteries causing ischemia of both the anterior and posterior segment.Citation22

Blood supply to optic nerve

The ophthalmic artery, a direct branch of the internal carotid artery, provides most of the blood supply to the eye. Its branches include the central retinal artery, the short and long posterior ciliary arteries, and the anterior ciliary arteries. It is generally agreed that the principal arterial supply to the anterior optic nerve is via the short posterior ciliary arteries. The central retinal artery mainly supplies the retina and superficial anterior optic nerve.

The vascular supply of the optic nerve is complex. The optic nerve head is divided into three regions, as follows:

The surface nerve fiber layer, which is primarily supplied by arterioles in the adjacent retina. These are branches of the central retinal artery arising in the peripapillary retina.

The prelaminar and laminar region are mainly supplied by branches from the short posterior ciliary arteries and the Zinn-Haller circle.

Tetrolaminar region, supplied by the pial arteries and branches arising from the short posterior ciliary arteries. Venous drainage is via the central retinal vein and pial veins.

Pathophysiology of ocular circulation in giant cell arteritis

Although giant cell arteritis can cause any lesion affecting the retina to the occipital lobe, the most common cause of vision loss in giant cell arteritis is anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in giant cell arteritis is the result of inflammatory occlusion of the short posterior ciliary arteries, which are the main source of blood supply to the optic nerve head. The cause for selective involvement of posterior ciliary arteries is not known. Posterior ciliary artery involvement in giant cell arteritis has been demonstrated on fluorescein fundus angiography and histopathological studies.Citation24

In his large series of giant cell arteritis patients, Hayreh has observed that visual loss is often discovered on waking up from sleep in the morning. The fall in blood pressure during sleep may act as the final insult to produce ischemia of the optic nerve head.Citation25

Less common causes of vision loss include central retinal artery occlusion, cilioretinal artery occlusion, choroidal infarction, posterior ischemic optic neuropathy, and cortical visual loss due to occipital infarction caused by vertebrobasilar stroke.Citation10,Citation18

In an elderly person, visual loss can be due to arteritic or nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Because the management approach is completely different for those two conditions, the following clues help in establishing an accurate and timely diagnosis ().

Table 1 Features of arteritic and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy

Investigations for diagnosing choroidal and optic nerve ischemia

Fluorescein and indocyanine angiography

Both fluorescein and indocyanine green angiographies are used to study the retinal, choroidal, and optic disc circulation. Angiography is very useful in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis during the early stages of visual loss to determine its cause. Hayreh has reported that, in almost every patient with giant cell arteritis, occlusion of the posterior ciliary artery was identified in patients with vision loss.Citation25 Angiography should be performed within the first days after onset of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy because with the passage of time collaterals develop and delays in choroidal filling cannot be appreciated.Citation26 In this imaging modality, sodium fluorescein is intravenously administered to the patient and the passage of fluorescein is observed first throughout the choroidal circulation and then in the retinal circulation. Prolonged choroidal filling time is a highly specific angiographic finding. A prolonged retinal artery and venous transit time is a very sensitive sign, but it can also be seen in association with central retinal artery occlusion or central retinal vein occlusion.Citation22 Extensive choroidal hypoperfusion and multiple filling defects on angiography are highly suggestive of arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.

Indocyanine green angiography allows better evaluation of the choroidal circulation. The view of the choroid is normally obscured during fluorescein angiography. Indocyanine green provides greater transmission through the retinal pigment epithelium than the visible wavelengths used in fluorescein angiography.Citation27 A part from choroidal ischemia, it also demonstrates staining of vessels, which may relate to inflammatory infiltration of the vessel wall.Citation28

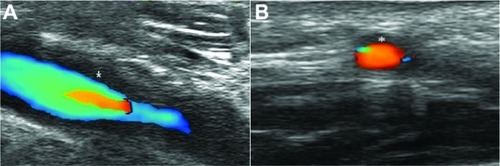

Ocular Doppler ultrasound

The color Doppler hemodynamics of giant cell arteritis has been studied in patients with a biopsy-proven diagnosis.Citation29 In a color Doppler ultrasound study, Ghanchi et al assessed the effects of giant cell arteritis on orbital blood flow. Absence of detectable blood flow in the posterior ciliary arteries was observed in six of seven patients.Citation30 Being noninvasive, color Doppler ultrasound allows monitoring of orbital blood flow which correlates with the clinical features of giant cell arteritis.Citation31,Citation32 Contrast-enhanced ultrasound has been shown to improve detection of orbital vessels that were otherwise insufficiently detectable.Citation33 A hyperechoic embolic occlusion of the central retinal artery in the area of the optic nerve head, referred as the retrobulbar “spot sign”, has recently been proposed to exclude giant cell arteritis.Citation34 The presence of the “spot sign” is suggestive of embolism, whereas vasculitic hypoperfusion is represented by absent or low-flow only.

Ocular pneumoplethysmography

Ocular pneumoplethysmography is a noninvasive method for detection of carotid occlusive disease. This technique has been used in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis.Citation35 It measures changes in the volume of the orbits resulting from changes in blood flow, thus indirectly recording ophthalmic artery pressure.Citation22 Pneumoplethysmography has been replaced by newer carotid artery imaging methods in the assessment of carotid artery disease.

Outcomes and costs related to sight loss

There are several reports of economic impact and the cost of visual impairment.Citation36,Citation37 Sight loss is particularly danger ous and disabling above the age of 65 yearsCitation37 due to falls, broken hips, other fractures, admission to nursing homes, loss of confidence, and depression. In a series from Southend Hospital (manuscript in preparation) of 11 patients with sight loss, three were deceased within 12 months, and all patients experienced severe depression related to loss of independence and mobility.

In reply to a parliamentary question on sight loss in giant cell arteritis, the Health Minister from the UK Department of Health (Hansard 1412, 2012)Citation38 replied that up to 3000 persons with giant cell arteritis in the UK may face visual loss every year (estimated from a giant cell arteritis incidence of 2.2/1000 patient years by Smeeth et alCitation8 and 25% incidence of sight loss at presentation). The Minister of Health admitted that this constitutes a large burden of disease and many cases could be prevented by earlier recognition and treatment.

Monocular or occasional binocular vision loss, particularly in the elderly, has major consequences for quality of life.Citation39 Patients with monocular vision loss are willing to trade one-in-three of their remaining lifetime for unimpaired vision. The trade-off rises to two-in-three for patients with binocular vision loss. According to the Royal National Institute of Blind People economics study, sight loss in the adult UK population imposes a large economic burden, totaling £6.5 billion in 2008. In addition, loss of healthy life and loss of life due to premature death associated with sight loss also impose a large cost on society. It is predicted that by 2020, the number of people with sight loss from all causes will rise to over 2,250,000 in the UK, and by 2050, this number will double to nearly four million.Citation40

Management and diagnostic strategies for giant cell arteritis

Constitutional symptoms

Most patients with giant cell arteritis have features of a systemic inflammatory response, with 50% patients developing systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and raised inflammatory markers.Citation41,Citation42 Large-vessel disease in giant cell arteritis may present without overt ischemic manifestations in a number of ways, including fever of unknown origin, unexplained anemia, a constitutional syndrome characterized by asthenia, anorexia, and weight loss, or isolated polymyalgia rheumatica refractory to steroids.Citation43

Cranial symptoms

Headache is the main symptom in more than 60% of patients.Citation44 This is usually a sudden-onset, severe, localized pain in the temporal region, but it may affect the occipital region and is sometimes poorly localized. Clinical findings include a tender, beaded, thickened and pulseless temporal artery. The scalp is also usually tender.

Large artery involvement

Large artery involvement with aortitis and upper limb arterial involvement (subclavian, axillary, brachial) can present with constitutional symptoms, upper extremity claudication, absent pulses or bruits in the neck and arms, or Raynaud’s phenomenon, and as polymyalgia rheumatica without adequate response to steroids. Aortic disease is generally observed as a late complication in the extended follow-up of patients with giant cell arteritis.Citation45 A report from the Mayo Clinic found that large artery complications occurred in 22%–27.3% of patients with giant cell arteritis, with an incidence of 30.5 per 1000 person-years at risk.Citation45 Overall, 18% of this cohort had aortic aneurysm or dissection, and 13% had large artery stenosis. Large artery involvement correlated negatively with cranial artery disease (hazard ratio 0.1) and with high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (hazard ratio 0.8). Angina pectoris, congestive heart failure, and myocardial infarction secondary to coronary arteritis have been reported.Citation46

Relationship between giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica

Giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica both affect elderly people, their genetic backgrounds are quite similar, and they are both generally responsive to corticosteroids. Polymyalgia rheu-matica is present in approximately 50% of patients with giant cell arteritis, and approximately 10% of polymyalgia rheumatica patients develop giant cell arteritis.Citation47 Polymyalgia rheumatica usually starts abruptly with pain and stiffness in the shoulder and pelvic girdles and neck.Citation48 There may also be systemic features including fever, malaise, and weight loss. Patients can also present with distal features, especially hand arthritis, tenosynovitis, and carpal tunnel syndrome.

Temporal artery biopsy

Temporal artery biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis and is desirable in all cases. Other tests used are imaging modalities such as duplex ultrasonography, FDG-PET, PET-computed tomography (CT) and MRI.

A temporal artery biopsy should be performed whenever diagnosis of giant cell arteritis is suspected. However, this should not delay treatment, and a contralateral biopsy is not routinely indicated unless the original is suboptimal. Temporal artery biopsy should be at least 1 cm, and preferably 2 cm, in length,Citation49 owing to the possibility of skip lesions. It should be noted that temporal artery biopsy may be negative in up to 45% of cases due to various factors, including suboptimal biopsy technique, temporal artery examination, skip areas, and the effect of preceding steroid therapy. A negative biopsy (in a setting of otherwise typical features of giant cell arteritis) does not exclude the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Temporal artery histology may remain positive 2–4 weeks after start of glucocorticoid therapy.

Imaging

Ultrasonography of axillary and temporal arteries

The “halo” sign in ultrasound is quite specific for temporal arteritis. Schmidt et al originally reported the ultrasound appearance of a hypoechoic halo around affected arteries in 1997 ().Citation50 Other ultrasonographic features include arterial occlusion and stenosis. A meta-analysis of 23 studies found the “halo” sign to have a pooled sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 82% compared with biopsy.Citation51 A large multicenter prospective comparative study in the UK of ultrasonography versus TAB in early giant cell arteritis (TABUL GCA) is testing the diagnostic accuracy, cost-effectiveness, and patient acceptability of the two procedures and whether duplex ultrasound should become routine clinical practice. Ultrasound of the axillary arteries may also give clues regarding large-vessel disease in giant cell arteritis.

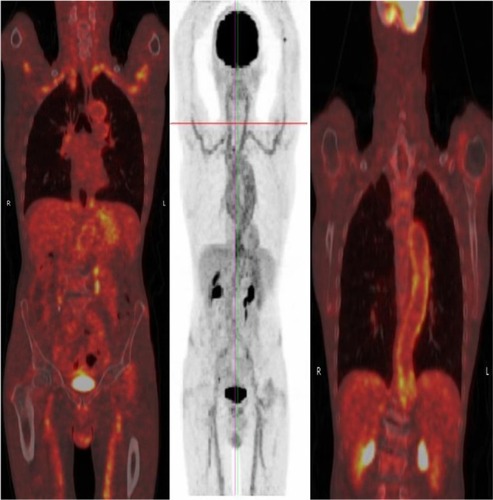

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

Vasculitis in the large vessels can be imaged with FDG-PET. Unfortunately, the temporal artery is not well visualized in PET owing to high activity in the surrounding brain. Blockmans et al studied 35 patients with early biopsy-positive giant cell arteritis.Citation52 At diagnosis, 29 patients (83%) had FDG uptake in at least one vascular territory. Subclavian involvement was most common (74%), followed by aortic (50%) and iliac/femoral involvement (37%). With treatment, there was a decrease in intensity of FDG uptake by 3 months. However, the authors found no correlation between PET findings and relapse. Another study showed that patients with giant cell arteritis and with increased FDG uptake in the aorta may be more prone to develop dilatation of the thoracic aortic than patients without increased uptake after a mean follow-up of 46.7 months.Citation53 This study suggests that FDG-PET scanning has prognostic significance.

FDG-PET-CT combines FDG-PET with CT scanning to show the anatomy of the lesion with superimposed metabolic activity (). It addresses the limitations of PET scanning alone (ie, the failure to localize the uptake anatomically and accurately) and may help in differentiating atherosclerosis from vasculitis because calcified plaques may be seen in atherosclerotic lesions. In a retrospective case notes review of 52 rheumatology patients with active polymyalgia rheumatica or giant cell arteritis despite optimal steroid/methotrexate therapy, 15 had strong FDG uptake in the sub-clavian, aortic, and axillary arteries, suggesting the presence of large vessel arteritis (manuscript in preparation). All had constitutional symptoms, notably night sweats, weight loss, and lethargy. The average C-reactive protein in patients with large-vessel vasculitis was 112 (range 13–403). There was equal representation of patients with polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis. In addition, FDG-PET-CT showed utility in detecting other serious pathology, including cancer in three cases and spondyloarthritis in two cases.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI findings include increased vessel wall thickness and edema, increased mural enhancement on post contrast T1-weighted images, and luminal stenosis on magnetic resonance angiography. Bley et al found that MRI of the temporal artery had a sensitivity of 80.6% and a specificity of 97.0% for diagnosis of giant cell arteritis by American College of Rheumatology criteria.Citation54

Treatment

Fast track recognition, referral, and treatment of giant cell arteritis

Analogous to the “Time is Brain” UK ACT-FAST campaign in stroke, “Time is Sight” has been proposed in giant cell arteritis. The key issues in management are urgent recognition and prompt institution of corticosteroid therapy. There is a major delay in instituting treatment for this critically ischemic disease, and a local audit at Southend Hospital in the UK showed that the mean time delay from symptom onset to start of steroids was 35 days. This delay in diagnosis and commencement of steroid therapy may explain the high incidence of irreversible visual complications.Citation55,Citation56 A fast track pathway for giant cell arteritis operational at Southend since 2011 has shown a dramatic reduction in irreversible sight loss from 23.3% to 7.6% (manuscript in preparation).

A UK Department of Health working group is now evaluating “rollout” of this fast track pathway across the UK. The following are the key areas to address: public awareness, professional awareness, improvement of skills and competence of front-line specialties, such as general practitioners; accident and emergency and acute physicians; treatment to be initiated at the first contact with health professional; easy accessibility of rheumatology consult; a one-stop shop with urgent same-day assessment and relevant investigations by a rheumatologist and/or ophthalmologist (blood tests, ultrasound of temporal arteries, and urgent temporal artery biopsy); and uniform implementation of diagnosis and management guidelines. Reducing unnecessary delays, and standardization of protocols for diagnosing and treating patients with giant cell arteritis may substantially decrease mortality and morbidity associated with sight loss and other ischemic complications. Better patient education should aim towards early identification of new disease, of relapses, minimize presentation delays, and improve adherence to treatment and prevention of steroid-associated adverse events.

Corticosteroid therapy

There are no trials comparing different steroid dosing regimens in giant cell arteritis. The recommendations are based on doses suggested in the British Society of Rheumatology guidelines for giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica and are mostly based on level 3 evidence.Citation49,Citation57

Early high-dose steroid treatment is essential for rapid symptom control and to prevent further visual loss as far as possible.Citation58 Improvement in symptoms often begins within hours to days after commencing steroids, with a median time to initial response to an average initial dose of 60 mg/day of 8 days.Citation59 However, there was little recovery in fixed visual deficits in the Mayo Clinic study. Initial high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone is often used in clinical practice when patients present with threatened vision.Citation58 However, this remains controversial despite findings demonstrating a reduction in cumulative steroid dosage after use of intravenous steroids.Citation60

Recommended starting doses of steroids

British Society of Rheumatology guidelines recommend the following starting doses for steroids:

Prednisolone 40–60 mg daily for uncomplicated giant cell arteritis (no jaw claudication or visual disturbance)

Intravenous methylprednisolone 500–1000 mg for 3 days before oral steroids for evolving visual loss (recent onset of visual symptoms over 6–12 hours) or amaurosis fugax (complicated giant cell arteritis)

Prednisolone 60 mg daily for established visual loss, to protect the contralateral eye

Treatment along the lines of systemic vasculitis protocols is recommended for large-vessel disease, although this needs to be individualized.

The initial high dose of steroids should be continued for 3–4 weeks and reduced in the absence of any clinical symptoms or any laboratory abnormalities suggestive of ongoing active disease. The steroid tapering should be gradual, provided there is no relapse. In all cases, bone protection should be prescribed according to local guidelines. Proton pump inhibitors should also be considered in most cases, particularly if aspirin is being coprescribed. Most patients are able to discontinue steroids after 1–2 years of treatment. However, the duration of therapy needed is very variable, with some patients experiencing a chronic relapsing course of disease.

Aspirin

Aspirin has been shown to suppress proinflammatory cytokines in vascular lesions in giant cell arteritis.Citation61 There are studies which have shown that antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy may reduce the risk of ischemic events in patients with giant cell arteritisCitation62,Citation63 while other studies have not.Citation9,Citation64–Citation66 Despite this, guidelines recommend the use of aspirin, given that ischemic complications are the biggest source of morbidity in giant cell arteritis.

Treatment of relapsing giant cell arteritis

Disease relapse in giant cell arteritis can be defined as a rise in erythrocyte sedimentation rate above 40 mm/h, plus a return of symptoms of giant cell arteritis, ischemic complications, unexplained fever, or symptoms of polymyalgia rheumatica.Citation67 It is usually managed by increasing the dose of steroid, depending on type of relapse and number of preceding relapses. Raised inflammatory markers alone do not indicate a relapse in disease, and should not prompt an increase in steroid dose. Management of relapse is as follows:

Return of headache should be treated with the most recent higher steroid dose

Jaw claudication requires prednisolone 40–60 mg

Recurrent eye symptoms require the use of either 60 mg of prednisolone or intravenous methylprednisolone

Symptoms of large-vessel disease (profound constitutional symptoms, high systemic inflammatory response, lack of response to steroids, limb claudication) should prompt further investigation with MRI or PET and use of treatment protocols for systemic vasculitis.

Long-term corticosteroid therapy is associated with a number of adverse effects, which affect up to 86% of patients.Citation68 Therefore, recurrent relapse or failure to wean steroid dosage requires the consideration of steroid-sparing strategies using disease-modifying immunosuppressive drugs. Immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate and leflunomide, should be considered at least at the third relapse. Earlier institution of immunosuppressive therapy may be considered, depending on severity and type of relapsing disease.

Oral immunosuppressive agents

Methotrexate may be used as a steroid-sparing drug. A meta-analysis of studies did suggest a steroid-sparing effect, with a modest effect on cumulative steroid dose.Citation69 Alternatively, azathioprine may be used as an adjuvant agent.Citation70 Leflunomide has been used for treatment of giant cell arteritis, and it has shown promise in a small number of patients with difficult to treat steroid-resistant disease in our center.Citation71 A multicenter randomized controlled trial is in the planning stages.

Biologic agents

Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy with infliximab has been tried in the management of giant cell arteritis and has not been found to be effective.Citation67 Etanercept has not yet been tested in a large trial, although in a small controlled study the results were inconclusive.Citation72 B-cell depletion by rituximab has been used as a steroid-sparing strategy in one patient, with evidence from PET scanning at 4.5 months indicating that the arteritis had resolved.Citation73 Another patient with giant cell arteritis and neutropenia was successfully treated with rituximab.Citation74 A trial of abatacept (a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen [CTLA]-4 fusion protein) in large-vessel vasculitis is currently underway. Recently, treatment with the interleukin-6 inhibitor, tocilizumab, has been shown to be effective in patients with giant cell arteritis.Citation75–Citation77 Tocilizumab is indicated in a subgroup of patients with giant cell arteritis and profound constitutional symptoms, a high systemic inflammatory response, and active disease, with involvement of the aorta and its main branches. Larger studies with this therapeutic agent are awaited.

Future directions

There is an immediate need for implementation of strategies for high-risk case detection and treatment, a fast track pathway, screening for aortic and large vessel disease, and biomarkers for assessment of disease activity, and damage in giant cell arteritis. Better treatments with an improved safety profile compared with steroids and novel clinical trials of cytokine blockade, such as interleukin-6 inhibition with tocilizumab, are required.

Regenerative therapies

The neuroprotective and regenerative potential of stem cells hold promise in the treatment of eye disorders secondary to optic nerve damage. Transplanted stem cells can secrete neuroprotective factors naturally or with the help of genetic engineering. These neurotrophins increase photoreceptor and retinal ganglion cell survival, and might even facilitate retinal ganglion cell axon regrowth in models of retinal disease, glaucoma, and surgical lesions.Citation78 The intravitreal and subretinal routes are the most commonly used transplant strategy. Another strategy is to inject stem cells into the optic nerve and optic tract lesions. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells injected into an optic tract lesion have been shown to contribute towards neural repair through rescue and regeneration of injured neurons in rats.Citation79 A study was conducted to assess the effect of autologous intravitreal application of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells in three human patients with end-stage macular degeneration and glaucoma.Citation80 Although this procedure did not result in an improvement of vision, it demonstrated the feasibility of intravitreal injection of autologous bone-marrow-derived cells into the vitreous cavity. We are not aware of trials of such regenerative therapies for optic nerve damage in giant cell arteritis.

Conclusion

Giant cell arteritis is now recognized as a critically ischemic disease where ischemic complications, large vessel involvement and adverse events from long-term, high-dose steroids may result in poor outcomes, morbidity, and even mortality, significant costs to health care, and a major impact on quality of life. Guidelines on diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis need implementation to address the wide variation of practice and lack of public and professional awareness of many aspects of this condition. A robust evidence base is lacking, despite the fact that this is the commonest cause of systemic vasculitis. Research programs to address better the understanding of biomarkers, and safer and more effective therapies are urgently needed.

Disclosure

BD has received honoraria for lectures and served on advisory boards for the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Roche, Munidpharma, Napp, Merck, and GSK, and has received grant support from the European League Against Rheumatism, American College of Rheumatology, Health Technology Assessment UK, and Research for Patient Benefit UK.

References

- SalvaraniCCantiniFBoiardiLHunderGGPolymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritisN Engl J Med2002347426127112140303

- GhoshPBorgFADasguptaBCurrent understanding and management of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumaticaExpert Rev Clin Immunol20106691392820979556

- MachadoEBMichetCJBallardDJTrends in incidence and clinical presentation of temporal arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950–1985Arthritis Rheum19883167457493382448

- SalvaraniCGabrielSEO’FallonWMHunderGGEpidemiology of polymyalgia rheumatica in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1970–1991Arthritis Rheum19953833693737880191

- Gonzalez-GayMAMiranda-FilloyJALopez-DiazMJGiant cell arteritis in northwestern Spain: a 25-year epidemiologic studyMedicine2007862616817435586

- SalvaraniCCrowsonCSO’FallonWMHunderGGGabrielSEReappraisal of the epidemiology of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, over a fifty-year periodArthritis Rheum200451226426815077270

- González-GayMAGarcía-PorrúaCVázquez-CarunchoMThe spectrum of polymyalgia rheumatica in northwestern Spain: incidence and analysis of variables associated with relapse in a 10 year studyJ Rheumatol19992661326133210381051

- SmeethLCookCHallAJIncidence of diagnosed polymyalgia rheumatica and temporal arteritis in the United Kingdom, 1990–2001Ann Rheum Dis20066581093109816414971

- BergerCTWolbersMMeyerPDaikelerTHessCHigh incidence of severe ischaemic complications in patients with giant cell arteritis irrespective of platelet count and size, and platelet inhibitionRheumatology (Oxford)200948325826119129348

- González-GayMAGarcía-PorrúaCLlorcaJVisual manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Trends and clinical spectrum in 161 patientsMedicine200079528329211039076

- SalvaraniCCiminoLMacchioniPRisk factors for visual loss in an Italian population-based cohort of patients with giant cell arteritisArthritis Rheum200553229329715818722

- EzeonyejiANBorgFADasguptaBDelays in recognition and management of giant cell arteritis: results from a retrospective auditClin Rheumatol201130225926221086005

- HayrehSSPodhajskyPAZimmermanBOccult giant cell arteritis: ocular manifestationsAm J Ophthalmol199812545215269559738

- BorgFASalterVLJDasguptaBNeuro-ophthalmic complications in giant cell arteritisCurr Allergy Asthma Rep20088432333018606086

- MackieSLDasguptaBHordonLIschaemic manifestations in giant cell arteritis are associated with area level socio-economic deprivation, but not cardiovascular risk factorsRheumatology (Oxford)201150112014202221859697

- HayrehSSPodhajskyPAZimmermanBOcular manifestations of giant cell arteritisAm J Ophthalmol199812545095209559737

- ReichKGiansiracusaDStrongwaterSNeurologic manifestations of giant cell arteritisAm J Med19968916772

- KawasakiAPurvinVGiant cell arteritis: an updated reviewActa Ophthalmol2009871133218937808

- ForoozanRBuonoLMSavinoPSergottRCTonic pupils from giant cell arteritisBr J Opthalmol2003874500519

- ShahAVPaul-OddoyeABMadillSAJeffreyMNTappinADMHorner’s syndrome associated with giant cell arteritisEye (Lond)200721113013116823463

- AhmadIZamanMBilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia: an initial presenting sign of giant cell arteritisJ Am Geriatr Soc199947673473610366177

- MendrinosEMachinisTGPournarasCJOcular ischemic syndromeSurv Ophthalmol201055123419833366

- AristodemouPStanfordMTherapy insight: the recognition and treatment of retinal manifestations of systemic vasculitisNat Clin Pract Rheumatol20062844345116932736

- HayrehSSZimmermanBManagement of giant cell arteritisOphthalmologica2003217423925912792130

- HayrehSSGiant cell arteritis (temporal arteritis)2011 Available from: http://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/component/content/article/112-gcaAccessed August 30, 2012

- ValmaggiaCSpeiserPBischoffPNiederbergerHIndocyanine green versus fluorescein angiography in the differential diagnosis of arteritic and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathyRetina199919213113410213239

- BennettTJBarryCJOphthalmic imaging today: an ophthalmic photographer’s viewpoint – a reviewClin Experiment Ophthalmol200937121318947332

- SadunFPeceABrancatoRFluorescein and indocyanine green angiography in arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathyBr J Ophthalmol1998821113441345

- HoACSergottRCRegilloCDColor Doppler hemodynamics of giant cell arteritisArch Ophthalmol199411279389458031274

- GhanchiFWilliamsonTHLimCSColour Doppler imaging in giant cell (temporal) arteritis: serial examination and comparison with non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathyEye199610Pt 44594648944098

- TranquartFBergèsOKoskasPColor Doppler imaging of orbital vessels: personal experience and literature reviewJ Clin Ultrasound200331525827312767021

- WilliamsonTHBaxterGPaulRDuttonGNColour Doppler ultrasound in the management of a case of cranial arteritisBr J Ophthalmol199276116906611477049

- BrabrandKKertyEJakobsenJAContrast-enhanced ultrasound Doppler examination of the retrobulbar arteriesActa Radiol200142213513911259938

- ErtlMAltmannMTorkaEThe retrobulbar spot sign in sudden blindness – sufficient to rule out vasculitis?Perspectives in Medicine201227 Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211968X12000551

- BosleyTMSavinoPJSergottRCOcular pneumoplethysmography can help in the diagnosis of giant-cell arteritisArch Ophthalmol198910733793812923561

- MeadsCWhat is the cost of blindness?Br J Ophthalmol200387101201120414507746

- TaylorHRPezzulloMLKeeffeJEThe economic impact and cost of visual impairment in AustraliaBr J Ophthalmol200690327227516488942

- AnonymousHouse of Lords Hansard for July 12, 2012 (Pt 1) Available from: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201213/ldhansrd/text/120712w0001.htmAccessed September 13, 2012

- FrostAEachusJSparrowJVision-related quality of life impairment in an elderly UK population: associations with age, sex, social class and material deprivationEye (Lond)200115Pt 673974411826994

- AnonymousKey information and statistics – RNIBRoyal National Institute of Blind People Available from: http://www.rnib.org.uk/aboutus/Research/statistics/Pages/statistics.aspx#H2Heading2Accessed September 2, 2012

- SalvaraniCMacchioniPLTartoniPLPolymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: a 5-year epidemiologic and clinical study in Reggio Emilia, ItalyClin Experiment Rheumatol198753205215

- Gonzalez-GayMAGarcia-PorruaCAmor-DoradoJCLlorcaJFever in biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis: clinical implications in a defined populationArthritis Rheum200451465265515334440

- Gonzalez-GayMAGarcia-PorruaCAmor-DoradoJCLlorcaJGiant cell arteritis without clinically evident vascular involvement in a defined populationArthritis Rheum200451227427715077272

- Gonzalez-GayMABarrosSLopez-DiazMJGiant cell arteritis: disease patterns of clinical presentation in a series of 240 patientsMedicine200584526927616148727

- NuenninghoffDMHunderGGChristiansonTJHMcClellandRLMattesonELIncidence and predictors of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: a population-based study over 50 yearsArthritis Rheum200348123522353114674004

- PennHDasguptaBGiant cell arteritisAutoimmun Rev20032419920312848946

- FranzénPSutinenSvon KnorringJGiant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica in a region of Finland: an epidemiologic, clinical and pathologic study, 1984–1988J Rheumatol19921922732761629827

- ChuangTYHunderGGIlstrupDMKurlandLTPolymyalgia rheumatica: a 10-year epidemiologic and clinical studyAnn Intern Med19829756726806982645

- DasguptaBBorgFAHassanNBSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of giant cell arteritisRheumatology20104911594159720371504

- SchmidtWAKraftHEVorpahlKVölkerLGromnica-IhleEJColor duplex ultrasonography in the diagnosis of temporal arteritisN Engl J Med199733719133613429358127

- KarassaFBMatsagasMISchmidtWAIoannidisJPAMeta-analysis: test performance of ultrasonography for giant-cell arteritisAnn Intern Med2005142535936915738455

- BlockmansDde CeuninckLVanderschuerenSRepetitive 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in giant cell arteritis: a prospective study of 35 patientsArthritis Rheum200655113113716463425

- BlockmansDCoudyzerWVanderschuerenSRelationship between fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the large vessels and late aortic diameter in giant cell arteritisRheumatology (Oxford)20084781179118418515868

- BleyTAUhlMCarewJDiagnostic value of high-resolution MR imaging in giant cell arteritisAJNR Am J Neuroradiol20072891722172717885247

- LoddenkemperTSharmaPKatzanIPlantGTRisk factors for early visual deterioration in temporal arteritisJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200778111255125917504884

- TarkkanenAGiant cell arteritis and the ophthalmologistActa Ophthalmol Scand200280435335412190775

- DasguptaBBorgFAHassanNBSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of polymyalgia rheumaticaRheumatology (Oxford)201049118619019910443

- HayrehSSZimmermanBVisual deterioration in giant cell arteritis patients while on high doses of corticosteroid therapyOphthalmology200311061204121512799248

- ProvenAGabrielSEOrcesCO’FallonWMHunderGGGlucocorticoid therapy in giant cell arteritis: duration and adverse outcomesArthritis Rheum200349570370814558057

- MazlumzadehMHunderGGEasleyKATreatment of giant cell arteritis using induction therapy with high-dose glucocorticoids: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized prospective clinical trialArthritis Rheum200654103310331817009270

- WeyandCMKaiserMYangHYoungeBGoronzyJJTherapeutic effects of acetylsalicylic acid in giant cell arteritisArthritis Rheum200246245746611840449

- NesherGBerkunYMatesMLow-dose aspirin and prevention of cranial ischemic complications in giant cell arteritisArthritis Rheum20045041332133715077317

- LeeMSSmithSDGalorAHoffmanGSAntiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with giant cell arteritisArthritis Rheum200654103306330917009265

- NarváezJBernadBGómez-VaqueroCImpact of antiplatelet therapy in the development of severe ischemic complications and in the outcome of patients with giant cell arteritisClin Experiment Rheumatol2008263 Suppl 49S57S62

- Gonzalez-GayMAPiñeiroAGomez-GigireyAInfluence of traditional risk factors of atherosclerosis in the development of severe ischemic complications in giant cell arteritisMedicine200483634234715525846

- SteichenOComment on: Risk factors for severe cranial ischaemic events in an Italian population-based cohort of patients with giant cell arteritisRheumatology (Oxford)2009489118019589889

- HoffmanGSCidMCRendt-ZagarKEInfliximab for maintenance of glucocorticosteroid-induced remission of giant cell arteritis: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2007146962163017470830

- HunderGGBlochDAMichelBAThe American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritisArthritis Rheum1990338112211282202311

- MahrADJoverJASpieraRFAdjunctive methotrexate for treatment of giant cell arteritis: an individual patient data meta-analysisArthritis Rheum20075682789279717665429

- De SilvaMHazlemanBLAzathioprine in giant cell arteritis/polymyalgia rheumatica: a double-blind studyAnn Rheum Dis19864521361383511861

- AdizieTChristidisDDharmapaliahCBorgFDasguptaBEfficacy and tolerability of leflunomide in difficult-to-treat polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell arteritis: a case seriesInt J Clin Pract201266990690922897467

- Martínez-TaboadaVMRodríguez-ValverdeVCarreñoLA double-blind placebo controlled trial of etanercept in patients with giant cell arteritis and corticosteroid side effectsAnn Rheum Dis200867562563018086726

- BhatiaAEllPJEdwardsJCWAnti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (rituximab) as an adjunct in the treatment of giant cell arteritisAnn Rheum Dis20056471099110015958774

- MayrbaeurlBHinterreiterMBurgstallerSWindpesslMThalerJThe first case of a patient with neutropenia and giant-cell arteritis treated with rituximabClin Rheumatol20072691597159817619810

- ChristidisDJainSDas GuptaBSuccessful use of tocilizumab in polymyalgic onset biopsy positive GCA with large vessel involvementBMJ Case Rep20112011 pii: bcr0420114135

- BeyerCAxmannRSahinbegovicEAnti-interleukin 6 receptor therapy as rescue treatment for giant cell arteritisAnn Rheum Dis201170101874187521515917

- SciasciaSRossiDRoccatelloDInterleukin 6 blockade as steroid-sparing treatment for 2 patients with giant cell arteritisJ Rheumatol20113892080208121885526

- Dahlmann-NoorAVijaySJayaramHLimbAKhawPTCurrent approaches and future prospects for stem cell rescue and regeneration of the retina and optic nerveCan J Ophthalmol201045433334120648090

- ZwartIHillAJAl-AllafFUmbilical cord blood mesenchymal stromal cells are neuroprotective and promote regeneration in a rat optic tract modelExp Neurol2009216243944819320003

- JonasJBWitzens-HarigMArsenievLHoADIntravitreal autologous bone-marrow-derived mononuclear cell transplantationActa Ophthalmol2010884e131e13219604156