Abstract

Background

HIV treatment programs are in need of brief, valid instruments to identify common mental disorders such as depression.

Aim

To translate and culturally adapt the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) for use in Uganda and to investigate its psychometric properties in this setting.

Methods

Following an initial translation of the SRQ-20 from English to Luganda, key informant interviews and focus-group discussions were used to produce a culturally adapted version of the instrument. The adapted SRQ-20 was administered to 200 HIV-positive individuals in a rural antiretroviral therapy program in southern Uganda. All study participants were also evaluated by a psychiatric clinical officer with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Receiver-operating-characteristic analysis was used to examine the sensitivity and specificity of the SRQ-20 compared to the clinical diagnosis generated by the MINI.

Results

The prevalence estimates of any depressive disorder and current depression were 24% (n = 48) and 12% (n = 24), respectively. The SRQ-20 scores discriminated well between subjects with and without current depression based on the MINI, with an area under the curve of 0.92, as well as between subjects with and without any current or past depressive disorder, with an area under the curve of 0.75. A score of 6 or more had 84% sensitivity and 93% specificity for current depression, and 75% sensitivity and 90% specificity for any depressive disorder.

Conclusion

The SRQ-20 appears to be a reliable and valid screening measure for depression among rural HIV-positive individuals in southern Uganda. The use of this screening instrument can potentially improve detection and management of depression in this setting.

Introduction

Since 2005, the expansion of antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs with increased ART provision in rural areas in sub-Saharan Africa has led to more research on mental health problems of HIV-positive individuals. In several sub-Saharan African studies, HIV-positive individuals using ART have been screened with various depression-screening instruments, resulting in rates of depression symptoms ranging from 14% to 81%.Citation1–Citation8 A few studies have assessed study participants further with diagnostic interviews. Six studies report on rates of current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)-defined major depression ranging from 14% to 34.9%.Citation9–Citation15 Studies from Uganda estimate rates of depression symptoms ranging from 30% to 54%.Citation16–Citation18

This variation in rates of depression may be explained by a variety of issues. The studies describing prevalence of depression in sub-Saharan Africa utilize a range of instruments to screen for depression symptoms. These instruments range from ultrashort questionnaires consisting of two or three questionsCitation2 to standard questionnaires consisting of more than 15 items.Citation4 The British National Clinical Practice Guidelines on management of depression in primary and secondary careCitation19 recommend that ultrashort tests should only be used when there are sufficient resources for second-stage assessment of those who screen positive. In low-resource settings like sub-Saharan Africa, it may not be cost-effective to use ultrashort screening tools because resources would then be needed for further evaluations on individuals who do not actually need them. A system of further evaluations should be in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up if patients are to benefit from screening for depression. Although this may come with additional costs of putting in place a referral system or training HIV care providers in screening and recognizing mental health problems, the benefits of sustaining and maintaining optimal levels of adherence to ART in such a low-resource setting may offset those costs.

In addition to thinking about the length of the measure and costs associated with its implementation, the lack of locally validated instruments may result in misclassification of cases and noncases. The use of only screening measures to diagnose depression brings the issue of case ascertainment into question and may explain why there is a wide variation in prevalence rates of depression in some HIV-positive populations in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation20,Citation21 To reduce the rate of false positives or negatives, screening measures should ideally be followed by diagnostic interviews for all individuals. Also, this would enable us to distinguish between unipolar and bipolar depression.

Although depression is not more prevalent among rural versus urban HIV-positive populations in Uganda,Citation22 there is less access to comprehensive mental health services in rural areas.Citation23 Consequently, those in rural areas experience higher levels of mental-disorder comorbidities. Screening for depression does not exist in the majority of rural ART programs in Uganda. This is problematic because depression results in poor adherence to ART leading to HIV disease progression and the emergence of drug-resistant strains of the HIV virus.Citation24,Citation25 Therapy for severe depression coupled with advanced HIV disease would be very costly for rural populations in Uganda, who survive on less than a dollar per day. Therefore, there is urgent need for early detection of depression that can be addressed through adapted talk therapies.Citation26,Citation27

To assist with the goal of establishing a method for early detection, in this study we describe the translation and cultural adaptation of a commonly used mental health screening instrument, the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20), from English to Luganda. We also report on psychometric evaluation of this instrument and validation against a clinician- administered structured interview among HIV-positive individuals in a rural ART program in southern Uganda.

Methods

Study setting

Translation and adaptation of the SRQ-20 questionnaire were conducted at the Butabika National Referral Hospital antiretroviral therapy (ART) program, located in the Ugandan capital, Kampala. In 2005, the hospital received support from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria through the Ugandan Ministry of Health to start their ART program. This ART program runs a clinic every Wednesday, where new and continuing patients receive clinical assessments depending on their presenting problems. To date, over 1000 HIV-positive individuals have initiated ART in this program.

Pilot testing, validity, and reliability testing were conducted in the Mitiyana hospital Mildmay HIV clinic, the site of subsequent research using the screening instruments. This hospital is situated in Mubende district in rural southern Uganda, a region that has ethnic homogeneity among its population and social stability. The Mitiyana hospital is the largest in the district and serves as a referral center for five other health centers in the district. The Mildmay HIV clinic was set up in this hospital in 2006 to offer comprehensive HIV treatment services.

Study measures

The Self-Reporting Questionnaire

The SRQ-20, a brief questionnaire that can be self- or interviewer-administered, is designed to screen for common mental disorders.Citation28 This questionnaire is recommended by the World Health Organization for screening common mental disorders such as depression in developing countries like Uganda. It has been successfully translated into at least 20 languages in several developing countries, with acceptable measures of reliability and validity.Citation29,Citation30 It has been described as a time- and cost-efficient instrument.Citation28

The SRQ consists of 20 items designed to identify common mental disorders, including depression and anxiety disorders. The time span for each item refers to the individual’s feelings over the past 30 days. A score of 1 indicates that the symptom was present during the past month; a score of 0 indicates the symptom was absent, with a maximum possible score of 20.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview depression module

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)Citation31 is a diagnostic structured interview that was developed for DSM-IV psychiatric disorders. It is organized in diagnostic sections. Using branching-tree logic, the MINI has two screening questions per disorder. Additional symptoms within each disorder section are asked only if the screening questions are positively endorsed. The psychometric properties of the MINI have not been described in Uganda; however, its depression diagnostic section has been translated and locally adapted in Luganda and previously used in this setting.Citation23 The depression diagnostic section consists of two screening questions, seven additional questions related to depression symptoms, and one question related to functional impairment. The two screening questions ask about the presence of depressed mood and loss of interest in daily activities over a period of 4 weeks in the recent past.

If either one of the questions was positively endorsed by a study participant, the clinician asked additional questions to explore for both current (the 4 weeks prior to the interview) and lifetime major depression. If neither of the screening questions were endorsed, the clinician asked additional questions to explore the presence of lifetime major depression. A diagnosis of current major depression was made if a study participant positively endorsed five or more questions related to depression symptoms and the one question related to functional impairment over the 4-week period prior to the interview. A diagnosis of lifetime major depression was made if a study participant positively endorsed five or more questions related to depression symptoms and the one question related to functional impairment beyond a 4-week period prior to the interview.

Translation and adaptation process

Initial translation of the SRQ-20 was conducted by clinically experienced mental health workers at the Butabika National Referral Hospital whose native language is Luganda and whose second language is English. To ensure semantic equivalence, the SRQ-20 items were translated and back-translated while making sure that the meaning of each item was the same after translation.Citation32 The translated questionnaire was distributed to male and female key informants: two psychiatrists, four psychiatric nurses, three clinical psychologists, eight mental health service users (patients), and three laypersons. Next, in-depth interviews were conducted with these key informants regarding whether the translated SRQ-20 items retained the original meaning and whether the local expressions of depression symptoms were used in the wording of the items.

In light of the information provided by the key informants, the translated questionnaire was revised. The revised translation was back-translated into English by a second translator and compared with the original version. An item in the questionnaire was considered problematic if the back-translation of that item did not have the same meaning as that of the original item. Problematic items were noted for discussion by the research team.

As a next step in cultural adaptation of the instrument, we convened a focus group of ten HIV-positive patients using ART at the Butabika Hospital outpatient center. Research assistants explained study procedures, and all ten participants provided informed consent. The ten participants were grouped into five pairs, and each pair was asked to read the items in the Luganda questionnaires and to note down problems of comprehension, language, and cultural relevance. For those who could not read, the research assistant read out the questionnaires. Each pair’s remarks were discussed between the research team and translators, with further adjustments made as outlined in the results section below. The final Luganda version of the SRQ-20 (available from the first author) was pilot-tested among a different group of ten HIV-positive patients attending the Butabika Hospital ART program and ten such patients at the Mitiyana district hospital Mildmay HIV clinic. No further adjustments to the translated and adapted questionnaire were deemed necessary based on the feedback from these groups.

Validity and reliability testing

Two hundred HIV-positive individuals were recruited from the Mitiyana hospital Mildmay HIV Clinic over a 5-week period. On a given clinic day, research assistants worked with clinic staff to obtain a register of clients who had come to the clinic on that day. The clients would be seated in the waiting area waiting for their turn to see the HIV care provider. Names of clients were called out ten at a time, and they were asked to identify themselves by a show of hands. These clients were individually approached by research assistants (at the level of nursing assistant), who explained study procedures, determined eligibility, and then obtained informed consent. Each client who gave informed consent was referred to a psychiatric nurse interviewer, who administered the Luganda-version SRQ-20. After this interview, the client was referred to a psychiatric clinical officer (PCO) with diploma-level training in clinical psychiatry, who administered the gold-standard diagnostic interview – the MINI depression and mania modules. The diagnostic interview was aimed at detecting current (the 4 weeks prior to the interview) and lifetime major depression or bipolar depression. The PCO was blinded to the results of the SRQ-20 interview. For this study, two psychiatric nurses were available to administer the SRQ-20, and two PCOs were available to administer the MINI. All interviewers were trained before data collection by the study’s principal investigator. Training included basic research ethics, the reading and discussion of the instrument, and role-playing exercises. The principal investigator also reviewed and coded all records from the interviews.

To evaluate test–retest reliability of the Luganda version of the SRQ-20, study participants who lived within 5 km of the clinic were requested to return within 1 week for retesting by the same psychiatric nurse. This request was made of all study participants fitting this criterion until a sample size of 30 was reached. All study participants asked to return for reevaluation agreed to do so. The reevaluation was completed within a 2-week period. To evaluate interrater reliability of the Luganda version of the SRQ-20, the first 20 study participants were interviewed by the two psychiatric nurses at separate times on the same day.

The research protocol was approved by the Makerere University College of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee and the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board as well as the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology.

Data analysis

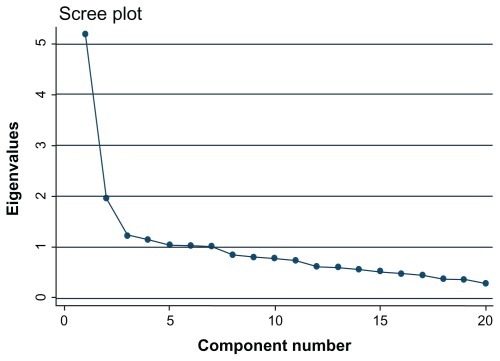

To assess interrater reliability and test–retest reliability, we computed Cohen’s kappa values.Citation33 Kappa is a reliability statistic that corrects for chance agreement. Kappa values of 0.40–0.60 are conventionally considered to represent moderate agreement, and values of 0.60–0.80 to represent good agreement.Citation34 The internal consistency of the Luganda-version SRQ-20 was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. To assess for construct validity, we performed principal-component analysis with varimax rotation. Factors with eigenvalues over 1.0 were then extracted. The optimal number of factors to be selected was chosen using the screeplot methodCitation35 (see ). To assess criterion validity of the Luganda-version SRQ-20, receiver-operating-characteristic analysis was performed using the MINI clinical assessment as the comparison criterion. The Stata (College Station, TX) 10 software package was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Translation and adaptation

The Self-Reporting Questionnaire

A number of SRQ-20 items needed to be fully revised to capture the idioms of distress in this population (see ). The items concerning poor digestion (item 7), ability to think clearly (item 8), crying more than usual (item 10), difficulty in making decisions (item 12), and daily work suffering (item 13) presented considerable problems in translation. Many subtle changes had to be made to these items to increase comprehension and relevance to the local population. For terms like ‘poor digestion,’ ‘daily work suffering,’ and ‘trouble thinking clearly,’ there were no exact substitutes in colloquial Luganda. Focus-group participants suggested that the various events that would indicate poor digestion, such as constipation, bloating, and heartburn, be included in this question to make it more easily understood by the study participants. The question ‘Is your daily work suffering?’ was rephrased to make it more understandable while retaining the original meaning.

The SRQ item ‘Do you have trouble thinking clearly?’ (item 8) was replaced by an item capturing ‘thinking too much,’ as our prior research into the expressions of depression by the local Baganda population had revealed that depression is often regarded as an illness of thoughts.Citation36 An individual with depression is referred to as ‘thinking too much’ and not regarded as having problems ‘thinking clearly.’ Focus-group participants suggested that this SRQ-20 item explore this cultural expression of depression.

The items concerning crying more than usual (item 10) and difficulty in making decisions (item 12) were straightforward. However, it was noted that these items were not culturally appropriate. Study participants said that in the local culture, it is taboo for men to cry. All male study participants assured us that no man would admit to crying. The men said that they do experience excessive sadness and may feel like crying, but they cannot cry. The translated version of this item considered this cultural taboo. Although the back-translated item deviated considerably from the original item, we decided to maintain the back-translated item because it was considered a more culturally acceptable question for both sexes.

Women, especially in rural areas, are often not as involved in decision-making, and some women participants of the focus group suggested that the item on decision-making might be irrelevant for female study participants. It was suggested that a better option might be to ask if they found it difficult to make routine housework decisions. Therefore, SRQ-20 item 12 was replaced by an item asking about decisions on household chores.

Criterion validity and reliability testing

Demographic information

Of the 200 individuals enrolled in the quantitative validation study, 33% were men and 67% were women. The mean ages of the men and women participants were 41.7 years (standard deviation [SD] = 11.1) and 39.1 years (SD = 12), respectively. Forty-two percent were peasant farmers, and 60% had attained partial primary education. The study population was poor, with 83% earning less than 75,000 Uganda shillings, which is equivalent to earning less than a dollar a day. summarizes demographic characteristics of this study population.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of HIV-positive individuals attending a rural antiretroviral therapy program in southern Uganda

Reliability testing of the SRQ-20

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the SRQ-20 was 0.84, which indicates a high level of homogeneity among items of the SRQ-20. Test–retest reliability was moderate, with 85% agreement between the first and second assessments (kappa = 0.48, SD = 0.16, P = 0.001). The two psychiatric nurses had 85% agreement with the SRQ-20 (kappa = 0.63, SD = 0.22, P = 0.002).

Construct validity of the SRQ-20

Principal-component analysis found two factors with an eigenvalue above 1, accounting for 87.1% of total variance. Specifically, factor 1 accounted for 67.6% of the total variance, while factor 2 accounted for 19.5% of the total variance. Item loading above 0.4 was used as a standard for allocating items to factors (). The subscales based on these two factors had good internal consistency as assessed by Cronbach’s alpha (subscale based on factor 1, α = 0.78; subscale based on factor 2, α = 0.72).

Table 2 Factor loadings using rotated varimax principal-component analysis of Self-Reporting Questionnaire items

Factor 1 was comprised of nine items (items 8, 10–16), these being questions about trouble thinking clearly, crying more, loss of interest in things, difficulty in making decisions, inability to enjoy daily activities, daily work suffering, inability to make decisions, and inability to play a useful part in life. This factor accurately described depressive symptoms, so it was named ‘depression.’

Factor 2 was comprised of eight items (items 2, 3–6, 18–20), these being questions about persistent headaches, feeling easily frightened, hands shaking, poor sleep, feeling nervous, tense, and worried, becoming easily tired, and uncomfortable feelings in the stomach. This factor more closely described anxiety symptoms, so it was named ‘anxiety.’

Criterion validity of the SRQ-20

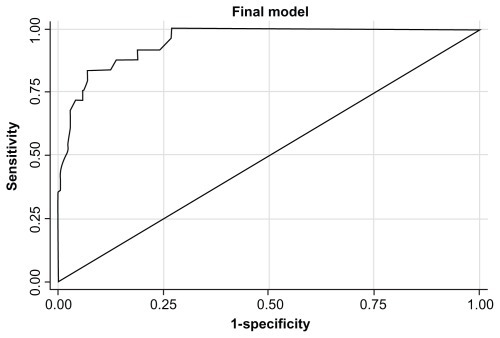

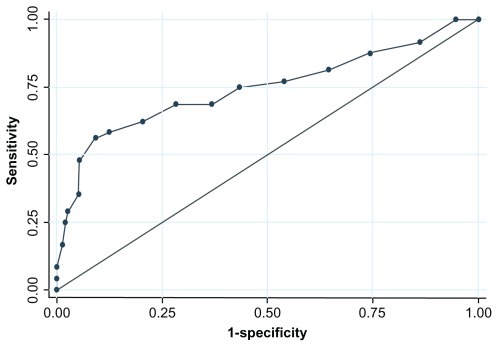

The SRQ-20 had excellent discriminatory power () for subjects with current depression (n = 24), as ascertained with MINI, with an area under the curve of 0.95, but only fair discriminatory power () for those with any depression (current and in the past; n = 48), with an area under the curve of 0.75. The area under the curve for detecting any depression (current and in the past) was similar between males (0.72) and females (0.73), those with primary or less education (0.73) and secondary education or more (0.83), subjects younger than 50 years old (0.75), and those who were 50 years and older (0.73). The optimal cutoff point of ≥6 scores had a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 93% for current depression and a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 90% for any depression. shows sensitivity and specificity of the SRQ-20 at different cutoff points for detecting current depression and any depression (current and in the past). Current or any depression ascertained by the MINI was not associated with any sociodemographic characteristic.

Figure 2 Receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve of the locally adapted Luganda version of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire for detection of a current depressive episode ascertained using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview in 200 HIV-infected individuals in a rural antiretroviral therapy program in southern Uganda.

Figure 3 Receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve of the locally adapted Luganda version of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire for detection of any depression (current and in the past) within 200 HIV-infected individuals in a rural antiretroviral therapy program in southern Uganda.

Table 3 Sensitivity and specificity of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire at different cutoff points in detecting current depression and any depression ascertained by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

Discussion

In this study, we translated and adapted into Luganda the SRQ-20 screening instrument for depression and assessed its psychometric properties, including test–retest and interrater reliability and also construct and criterion validity. In the translation of the SRQ-20 from English to Luganda, some words and/or phrases were difficult to translate, and as such required the use of alternative conceptually equivalent terms. Some questions like ‘Do you cry more than usual?’ were culturally offensive to men because in the local Buganda culture, it is a firmly held attitude that men should not cry. The challenges we experienced in translating the SRQ-20 to Luganda are not unique; similar challenges have been noted in previous attempts to translate Western-developed instruments into other languages for use in other cultural settings.Citation37 Nevertheless, this exercise is important, because research has shown that culture affects the presentation of most mental disorders. Citation38 There is evidence that the use of culturally adapted measures of mental health problems enhances the detection and diagnosis of these problems.Citation39–Citation41

Overall, five items in the original version of the SRQ-20 were adapted to suit the local culture. We found the locally adapted Luganda version of the SRQ-20 to be a reliable and valid screening instrument for current major depression and any depression (current and in the past) among rural HIV-positive populations in southern Uganda. In keeping with findings from a previous study,Citation42 principal-component analysis revealed that depression symptoms accounted for the largest portion of the total variance. At a cutoff point of ≥6 scores, the measure was able to correctly identify true cases of current depression and true noncases 84% and 93% of the time, respectively. At the same cutoff point, the measure was able to correctly identify true cases of any depression and true noncases 75% and 90% of the time, respectively.

The optimal cutoff point of the SRQ-20 has been found to differ among countries. Among non-HIV-positive populations, some studiesCitation38,Citation42,Citation43 report an optimal cutoff point of 6/7, and othersCitation44,Citation45 have used the 7/8 cutoff point. Previously in Uganda, the translated but not locally adapted SRQ-20 was used to screen for depression among general hospital patients. At a cutoff point of 5, the measure attained a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 74%.Citation46

A few depression-screening instruments that have been validated among HIV-positive populations in sub-Saharan Africa have yielded lower values of sensitivity and specificity. Spies et alCitation10 report that the Kessler-10 screening instrument for current depression attained only 67% sensitivity and 77% specificity among HIV-positive individuals in South Africa. Their study population spoke three different local languages, and the local adaption of the Kessler-10 was not described. It is possible that the local adaptation of the SRQ-20 may have enhanced its sensitivity and specificity.

Demographic and socioeconomic factors have also been shown to affect the choice of the cutoff point in non-HIV-positive populations. Results of previous studies suggest that females, the elderly, and poorly educated people tend to overreport symptoms on the SRQ-20 compared to a diagnostic interview.Citation29,Citation44,Citation45,Citation47 However, in this study the validity of the SRQ-20 was not affected by gender, age, or education status. The areas under the receiver-operating curve for current major depression and any depressive disorder did not differ as a function of age, gender, or education status, suggesting that it can be confidently used in our heterogeneous group of patients. Furthermore, none of the sociodemographic characteristics was associated with current major depression or any depression. This is in contrast to what has been reported regarding depression in non-HIV-positive populations, where the elderly and females tend to have higher rates of depression. Citation47 If corroborated in future studies from this setting, our findings suggest that the epidemiology and pathophysiology of depression in HIV-positive individuals may be different from that of depression in non-HIV-positive populations.

There are three other noteworthy findings from this study that warrant further investigation. First, the most frequently endorsed symptoms on the SRQ-20 in this study population were somatic complaints. Depressed individuals were more likely to endorse somatic complaints than nondepressed individuals. Also, depressed individuals were more likely to endorse somatic symptoms than depression symptoms. This finding adds strength to a previous finding that among the Baganda, depression is often expressed as somatic complaints.Citation36,Citation48 Thus, elimination of somatic symptoms from instruments screening for depression among the Baganda may lower the sensitivity of the screening instrument. Also, measures such as Kessler-10 that focus on psychological symptoms of mental disorders may underestimate the prevalence of mental health problems in these settings. Second, 14.5% of those with any depressive disorder were diagnosed with bipolar depression, suggesting that screening for depression needs to be followed by diagnostic interviews in order to differentiate unipolar from bipolar depression – conditions that require different treatments. Third, having a current major depression was associated with a past history of major depression. This finding suggests that a past history of depression should alert the clinicians to monitor their patients for recurrent depression symptoms. The cross-sectional nature of this study and the relatively small sample size limit our interpretation of this finding. We plan to investigate this finding further using case-control and prospective study designs in the future.

This study has some limitations. First, the use of the MINI diagnostic interview as the gold standard may not be appropriate, because its psychometric properties have not been determined in Uganda. However, the interviewers were clinicians who exercised their clinical judgment in interpreting the participants’ responses to the MINI questions. Second, study findings may not be generalizable to the entire population of HIV-positive individuals. Because of our recruitment strategy through clinics and inclusion criteria (HIV-infected, outpatients, and currently on ART), participants in this study may have had different physical, psychological, and behavioral characteristics than populations not connected to a clinic and/or not currently on ART. Lastly, all our study participants were outpatients at the time of evaluation. Although it is encouraging that we observed no differences in SRQ-20 performance by age, gender, or educational status, it would be beneficial to evaluate this measure among inpatient HIV-positive populations so as to ensure that its psychometric properties are stable across severity levels.

Because depression is common among rural HIV-positive populations and has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality,Citation49–Citation52 systematic screening for depression symptoms should be considered in all HIV-positive individuals. The patient or the health-care provider may erroneously consider symptoms of depression as expected physical effects of HIV, or these symptoms may be missed in the context of a busy clinic. We feel that the 20 brief question items in the SRQ-20 can easily be administered to patients as they wait their turn to see the doctor, thus enhancing case finding and treatment of depression in ART programs in Uganda.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the directors of the Mityana hospital HIV clinic and Mildmay Uganda Drs Samuel Steven Mwesigwa, Vincent Kawooya, Emmanuel Luyirika, and Ekiria Kikule for permitting and facilitating the study activities. We appreciate the diligent work of our research assistants: Jalia Nakaweesa, Hajara Nakyejwe, Rita Nanono, Tadeo Nsubuga, Elizabeth Nakanjako, and Kassim Magoba. Last, we thank the participants for their time and trust. This study was supported by the International Fulbright Science and Technology Award to Etheldreda Nakimuli-Mpungu in 2007.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- DoNTPhiriKBussmannHGaolatheTMarlinkRGWesterCWPsychosocial factors affecting medication adherence among HIV-1 infected adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in BotswanaAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses201026668569120518649

- EtienneMHossainMRedfieldRStaffordKAmorosoAIndicators of adherence to antiretroviral therapy treatment among HIV/AIDS patients in 5 African countriesJ Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic)2010929810320207981

- PeltzerKFriend-du PreezNRamlaganSAndersonJAntiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South AfricaBMC Public Health20101011120205721

- KageeAMartinLSymptoms of depression and anxiety among a sample of South African patients living with HIVAIDS Care201022215916520390494

- KaharuzaFMBunnellRMossSDepression and CD4 cell count among persons with HIV infection in UgandaAIDS Behav200610Suppl 4S105S11116802195

- PoupardMNgom GueyeNFThiamDQuality of life and depression among HIV-infected patients receiving efavirenz- or protease inhibitor-based therapy in SenegalHIV Med200782929517352765

- AmberbirAWoldemichaelKGetachewSGirmaBDeribeKPredictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons: a prospective study in southwest EthiopiaBMC Public Health2008826518667066

- CohenMHFabriMCaiXPrevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in HIV-infected and at-risk Rwandan womenJ Womens Health (Larchmt)200918111783179119951212

- MyerLSeedatSSteinDJMoomalHWilliamsDRThe mental health impact of AIDS-related mortality in South Africa: a national studyJ Epidemiol Community Health200963429329819074926

- SpiesGKaderKKiddMValidity of the K-10 in detecting DSM-IV-defined depression and anxiety disorders among HIV-infected individualsAIDS Care20092191163116820024776

- MyerLSmitJRouxLLParkerSSteinDJSeedatSCommon mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scalesAIDS Patient Care STDS200822214715818260806

- AdewuyaAOAfolabiMOOlaBARelationship between depression and quality of life in persons with HIV infection in NigeriaInt J Psychiatry Med2008381435118624016

- MarwickKFKaayaSFPrevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in HIV-positive outpatients in rural TanzaniaAIDS Care201022441541920131127

- OlleyBOSeedatSSteinDJPersistence of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa: a 6-month follow-up studyJ Psychosom Res200661447948417011355

- LawlerKMosepeleMSeloilweEDepression among HIV-positive individuals in Botswana: a behavioral surveillanceAIDS Behav200915120420819821023

- Nakimuli-MpunguEMutambaBOthengoMMusisiSPsychological distress and adherence to highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) in Uganda: a pilot studyAfr Health Sci20099 Suppl 1S2S720589156

- WeidlePJWamaiNSolbergPAdherence to antiretroviral therapy in a home-based AIDS care programme in rural UgandaLancet200636895471587159417084759

- NakasujjaNSkolaskyRLMusisiSDepression symptoms and cognitive function among individuals with advanced HIV infection initiating HAART in UgandaBMC Psychiatry20101014420537129

- KendrickTPevelerRGuidelines for the management of depression: NICE work?Br J Psychiatry201019734534721037209

- MajMSatzPJanssenRWHO neuropsychiatric AIDS study, cross-sectional phase II. Neuropsychological and neurological findingsArch Gen Psychiatry199451151618279929

- ShachamEReeceMOng’orWOOmolloOBastaTBA cross-cultural comparison of psychological distress among individuals living with HIV in Atlanta, Georgia, and Eldoret, KenyaJ Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic)20109316216920530470

- MusisiSKinyandaEEmotional and behavioural disorders in HIV seropositive adolescents in urban UgandaEast Afr Med J2009861162419530544

- MuhweziWWOkelloESNeemaSMusisiSCaregivers’ experiences with major depression concealed by physical illness in patients recruited from central Ugandan primary health care centersQual Health Res20081881096111418650565

- HendershotCSStonerSAPantaloneDWSimoniJMAlcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysisJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200952218020219668086

- GonzalezJSBatchelderAWPsarosCSafrenSADepression and HIV/AIDS treatment nonadherence: a review and meta-analysisJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201158218118721857529

- BoltonPBassJNeugebauerRGroup interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: a randomized controlled trialJAMA2003289233117312412813117

- VerdeliHCloughertyKBoltonPAdapting group interpersonal psychotherapy for a developing country: experience in rural UgandaWorld Psychiatry20032211412016946913

- World Health OrganizationA User’s Guide to the Self Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ)GenevaWHO1994

- ArayaRWynnRLewisGComparison of two self administered psychiatric questionnaires (GHQ-12 and SRQ-20) in primary care in ChileSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol19922741681731411744

- GiangKBAllebeckPKullgrenGTuanNVThe Vietnamese version of the Self Reporting Questionnaire 20 (SRQ-20) in detecting mental disorders in rural Vietnam: a validation studyInt J Soc Psychiatry200652217518416615249

- SheehanDVLecrubierYSheehanKHThe Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10J Clin Psychiatry199859Suppl 202233 quiz 34–579881538

- FlahertyJAGaviriaFMPathakDDeveloping instruments for cross-cultural psychiatric researchJ Nerv Ment Dis19881762572633367140

- CohenJA coefficient of agreement for nominal scalesEduc Psychol Meas1960203746

- FleissJLThe Design and Analysis of Clinical ExperimentsNew YorkWiley1986

- ZwickWVelicerWComparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retainPsychol Bull198699432442

- OkelloESEkbladSLay concepts of depression among the Baganda of Uganda: a pilot studyTranscult Psychiatry200643228731316893877

- BassJKBoltonPAMurrayLKDo not forget culture when studying mental healthLancet2007370959191891917869621

- CaninoGBravoMThe translation and adaptation of diagnostic instruments for cross-cultural useShafferDLucasCPRichtersJEDiagnostic Assessment in Child and Adolescent PsychopathologyNew YorkGuilford Press1999

- BassJKRyderRWLammersMCMukabaTNBoltonPAPost- partum depression in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: validation of a concept using a mixed-methods cross-cultural approachTrop Med Int Health200813121534154218983279

- BoltonPWilkCMNdogoniLAssessment of depression prevalence in rural Uganda using symptom and function criteriaSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200439644244715205728

- BetancourtTSBassJBorisovaIAssessing local instrument reliability and validity: a field-based example from northern UgandaSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol200944868569219165403

- ChenSZhaoGLiLWangYChiuHCaineEPsychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Self-Reporting Questionnaire 20 (SRQ-20) in community settingsInt J Soc Psychiatry200955653854719592444

- Al-SubaieASMohammedKAl-MalikTThe Arabic self-reporting questionnaire (SRQ) as a psychiatric screening instrument in medical patientsAnn Saudi Med199818430831017344679

- HarphamTReichenheimMOserRMeasuring mental health in a cost-effective mannerHealth Policy Plan200318334434912917276

- SartoriusNJancaAPsychiatric assessment instruments developed by the World Health OrganizationSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol199631255698881086

- NakiguddeJTugumisirizeJMusisiSValidation of the SRQ-20 in primary care in UgandaProceedings of the First Annual Makerere University Faculty of Medicine Scientific ConferenceNovember 24–25, 2005Entebbe

- LudermirABLewisGInvestigating the effect of demographic and socioeconomic variables on misclassification by the SRQ-20 compared with a psychiatric interviewSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol2005401364115624073

- OkelloESNeemaSExplanatory models and help-seeking behavior: pathways to psychiatric care among patients admitted for depression in Mulago hospital, Kampala, UgandaQual Health Res2007171142517170240

- LesermanJPenceBWWhettenKRelation of lifetime trauma and depressive symptoms to mortality in HIVAm J Psychiatry2007164111707171317974936

- PenceBWMillerWCGaynesBNEronJJJrPsychiatric illness and virologic response in patients initiating highly active antiretroviral therapyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200744215916617146374

- PenceBWMillerWCWhettenKEronJJGaynesBNPrevalence of DSM-IV-defined mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in an HIV clinic in the southeastern United StatesJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200642329830616639343

- HorbergMASilverbergMJHurleyLBEffects of depression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy and on clinical outcomes in HIV-infected patientsJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200847338439018091609