Abstract

This article proposes a number of recommendations for the treatment of generalized social phobia, based on a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. An optimal treatment regimen would include a combination of medication and psychotherapy, along with an assertive clinical management program. For medications, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and dual serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are first-line choices based on their efficacy and tolerability profiles. The nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitor, phenelzine, may be more potent than these two drug classes, but because of its food and drug interaction liabilities, its use should be restricted to patients not responding to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. There are other medication classes with demonstrated efficacy in social phobia (benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, alpha-2-delta ligands), but due to limited published clinical trial data and the potential for dependence and withdrawal issues with benzodiazepines, it is unclear how best to incorporate these drugs into treatment regimens. There are very few clinical trials on the use of combined medications. Cognitive behavior therapy appears to be more effective than other evidence-based psychological techniques, and its effects appear to be more enduring than those of pharmacotherapy. There is some evidence, albeit limited to certain drug classes, that the combination of medication and cognitive behavior therapy may be more effective than either strategy used alone. Generalized social phobia is a chronic disorder, and many patients will require long-term support and treatment.

Introduction

Social phobia (also known as social anxiety disorder) is an anxiety disorder in which there is a “marked and persistent fear of social or performance situations in which embarrassment may occur”.Citation1 It was first included in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1980Citation2 and is included in the section on anxiety disorders. DSM has the specifier of “generalized” relating to when fears are related to most social situations. By exclusion, the unspecified “nongeneralized” form relates to specific situations, and in the literature is often referred to as “nongeneralized social phobia”. For the remainder of this article, we have chosen to focus on generalized social phobia (hereafter simply referred to as social phobia). Generalized social phobia is the more relevant disorder to general psychiatric clinical work.

Social phobia has an early onset, with the median age of onset in the National Comorbidity Survey of 16 years.Citation3 The most commonly reported fears relate to public speaking or speaking up in a meeting or a class.Citation4 The disorder is associated with significant disability. Patients with social phobia are more likely to utilize medical outpatient clinics, receive lower incomes, be less likely to earn college degrees, or attain managerial, technical, or professional occupationsCitation3,Citation5,Citation6 than people not suffering with social phobia. They are also more impaired in family relationships, romantic relationships, and desire to live, with 21.9% having attempted suicide.Citation6,Citation7 The course of social phobia tends to be chronic, with a long duration of illnessCitation8 and low rates of recovery.Citation9

Social phobia has a high degree of comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders. Eighty-one percent of people suffering from social phobia reported at least one other lifetime DSM-IIIR disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey.Citation3 The odds ratio (OR) of having a second anxiety disorder is increased (range 7.1–8.7).Citation3 Between 16.6%Citation10 and 35.8%Citation6 of sufferers experience major depressive disorder, with social phobia preceding the onset of major depressive disorder by 12 years.Citation6 Rates of concurrent alcohol dependence are 27.3%, and concurrent alcohol abuse occurs in 11.3%Citation6 to 20.9%Citation10 of patients with social phobia. For patients with social phobia and a comorbid alcohol misuse disorder, almost 80% developed social phobia before the alcohol misuse disorder.Citation11 This seems to be the pattern with other comorbid conditions, with social phobia being the primary disorder in 71.4%.Citation3,Citation6 Patients who have social phobia and a comorbid alcohol disorder have an increased rate of comorbid psychiatric disorders, with 97% having at least one additional Axis I disorder, and 71.7% having a personality disorder.Citation11

Recent data from the cross-sectional World Mental Health surveysCitation12 provide cross-national comparisons of social phobia diagnosed by DSM-IV Composite International Diagnostic Interview in the general populations of developed and developing countries. These data show great variation in 12-month prevalence. Rates are lowest in China and Japan (0.3% and 0.5%, respectively), range from 0.6% to 1.4% in European countries, and are somewhat higher in the Ukraine (1.5%), South Africa (1.9%), Mexico (1.9%), and Colombia (2.8%). Rates then jump to 5.1% in New Zealand and 6.8% in the US. Explanations for these differences are likely to include both substantive and methodological reasons. The World Mental Health survey data indicate that social phobia has one of the earliest ages of onset amongst the mental disorders and yet is also one of the most undertreated anxiety disorders. Data from the New Zealand survey, the largest of the World Mental Health collaborating surveys, show that fewer than 5% of those meeting the criteria for social phobia sought treatment in the year of onset, and only 36% of those with a lifetime diagnosis of social phobia sought treatment from a health professional at some stage.Citation12 This latter statistic compares with 57% for generalized anxiety disorder, 63% for panic disorder, 54% for agoraphobia, and 50% for post-traumatic stress disorder.

There are a number of treatment options for social phobia, including medication, psychotherapy, and their combination. Although there have been a number of reviews of medications,Citation13,Citation14 psychological treatment,Citation15,Citation16 and combined treatmentsCitation17,Citation18 for social phobia, and the development of clinical guidelines,Citation18 there has been no synthesis of these data to identify characteristics for optimal overall management of social phobia. Patients with social phobia are difficult to engage with psychiatric services, and to date there are no published data to identify how to improve treatment engagement or adherence. The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to identify optimal treatments for social phobia, based on a systematic review of published clinical trial data.

Methods

Meta-analysis of treatment trials

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials using drugs, psychotherapy, or their combination, in social phobia. For the drug trials, the search methods were intended to identify all randomized, double-blind, parallel-group treatment trials in social phobia. For the psychological treatment trials, the search aimed to identify all randomized controlled trials (RCT). The search included published and unpublished studies, electronic database searches, searches of clinical and pharmaceutical trial registers, and personal communication with study authors. Studies were identified and obtained between September 2011 and January 2012 using electronic databases (Embase [1974 to the present] and Medline [1950 to the present]); reference lists of identified articles and other electronic search tools; clinical trials websites (http://www.clinicalstudyresults.org, http://clinicaltrials.gov, http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/); and, when required, communication with study authors. The following Boolean phrases were used when searching electronic databases and other electronic search engines: “randomized controlled trial”, “treatment”, “drug”, “psychotherapy”, “psychological treatment”, “cognitive behavior therapy”, “cognitive therapy”, “exposure therapy”, “social phobia”, and “social anxiety disorder”.

Inclusion criteria

We sought to identify RCT, either placebo-controlled or active-controlled. Only publications in English were considered. Studies that did not include information on treatment outcome were excluded. Study participants were adults who were diagnosed with DSM-III, DSM-III-R, or DSM-IV criteria for social phobia/social anxiety disorder. Data from maintenance or discontinuation phases were not collected. We did not include trials of exploratory agents, eg, neurokinin-1 antagonists or d-cycloserine, in this review. The relevance of identified papers was initially screened using title and abstract. Full manuscripts of studies of interest were screened according to inclusion criteria. Social phobia treatment studies involving medications generally include a range of clinician-rated and patient-rated outcome measures. For this analysis, we chose one endpoint, ie, the proportion of responders based on clinician assessments. In most studies, a responder was defined as someone who achieved a score of 1 or 2 on the seven-point Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGI) scale.Citation19 This represents a rating of score of very much or much improved (score of 1 or 2, respectively). In four studies, response was defined as a 50% reduction in a clinician-rated instrument (eg, Liebowitz Social Anxiety ScaleCitation107 or Hamilton Anxiety ScaleCitation108) or, in one case, a self-rated instrument (Fear Questionnaire)Citation109. Previous meta-analyses have shown that changes in the CGI are broadly similar to changes in other clinician-rated and patient-rated instruments.Citation20,Citation21 The majority of comparative psychotherapy trials do not report responder rates, so a narrative review is provided.

Data synthesis and analysis

All analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.0 (Cochrane Collaboration, 2008; http://www.cc-ims.net/RevMan). For rates of treatment response, Mantel-Haenszel OR were calculated using a random effects model. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity.

Results

Study identification and selection

The search strategy identified 410 papers. Based on a review of study title and abstract, 183 were selected for detailed review. Reasons for noninclusion included ineligible study design (eg, nonblinded dosing, continuation treatment trial, crossover trial), response data not provided in results, duplicate data presentation, and review articles. Ultimately, 41 papers were selected for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Antidepressant drugs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

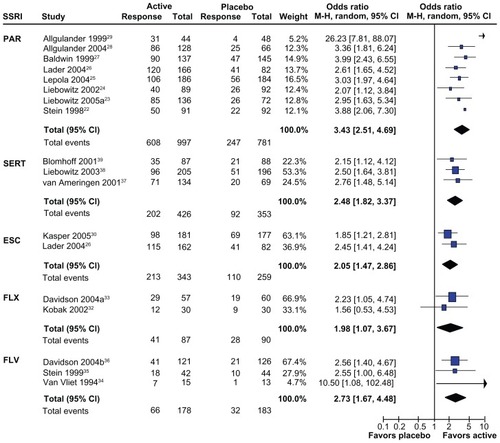

This class of drugs is the most extensively tested in patients with social phobia, with 17 placebo-controlled acute treatment RCT reported. Almost half of the studies studied paroxetine,Citation22–Citation29 with 2–3 studies each for escitalopram,Citation26,Citation30 fluoxetine,Citation31–Citation33 fluvoxamine,Citation34–Citation36 and sertraline.Citation37–Citation39 The pooled OR for response to each selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) ranges between 1.98 for fluoxetine and 3.41 for paroxetine (). With one exception, SSRIs had significantly greater CGI response rates compared with placebo. The single negative study (fluoxetine)Citation32 was of adequate duration and used a high fluoxetine dose (60 mg/day), but was relatively small in size (n = 30 per arm), and may thus have been underpowered to show a difference from placebo. There was significant heterogeneity associated with one study,Citation29 but its exclusion in a sensitivity analysis had little effect on the pooled OR for paroxetine studies (3.43 decreased to 3.09). In general, SSRIs showed separation from placebo by weeks 4–6 on a number of response or other outcome measures, however SSRI-placebo differences tended to increase out to 12 weeks of treatment. There have been four studies assessing the effect of continuation treatment with SSRIs in patients who have responded to acute treatment. Citation40–Citation43 In these relapse prevention studies, patients were randomized to remain on their SSRI or were switched to placebo, under double-blind conditions. All four studies showed robust effects of the SSRIs in preventing relapse of social phobia (pooled OR 0.25, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.18–0.35).Citation44

Figure 1 Odds ratios and 95% CI for treatment response in randomized placebo-controlled trials for SSRI. Response based on CGI for all studies except for Liebowitz Social Anxiety ScaleCitation107 in van Vliet et al.Citation34 Only the highest ESC dose included for Lader et al.Citation26

Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

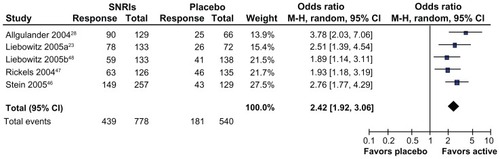

Venlafaxine is the only serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) studied in RCT in patients with social phobia, but improvements in social phobia symptom ratings have also been shown in an open-label trial of the SNRI, duloxetine.Citation45 All five reported studiesCitation23,Citation28,Citation46–Citation48 have shown significantly greater response rates for venlafaxine compared with placebo (, OR range for treatment response 1.89–3.78). Four of five studies used flexible dosing, with mean daily doses of approximately 200 mg/day. The single fixed-dose comparison studyCitation46 showed no differences in outcome measures between 75 mg/day and 150–225 mg/day dose arms, and both separated from placebo. The onset of response across all trials was evident at 4–6 weeks, although maximum separation from placebo continued out to 12 weeks.

Figure 2 Odds ratios and 95% CI for treatment response in randomized placebo-controlled trials for the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, venlafaxine. Response based on CGI for all studies.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

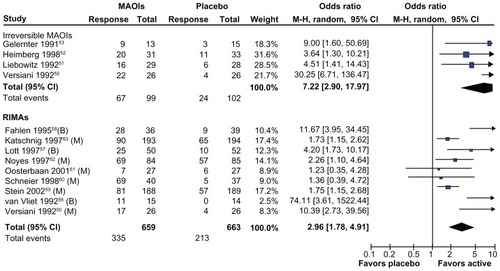

The first placebo-controlled RCT in social phobia assessed phenelzine, an irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitor. The rationale for using monoamine oxidase inhibitors was because social phobia and atypical depression share the symptom of increased interpersonal sensitivity, and atypical depression is preferentially responsive to monoamine oxidase inhibitors.Citation49 All four studies with this drugCitation50–Citation53 showed a significantly greater treatment response compared with placebo; however the pooled OR is heavily influenced by the results from one studyCitation50 (, upper panel). Exclusion of this studyCitation50 in a sensitivity analysis reduced the pooled OR from 7.22 to 4.58. There have also been positive open-label studies with tranylcypromine.Citation54 Reversible selective inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A were developed with the intention of reducing safety concerns due to drug and food interactions with the original nonselective irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors.Citation55 RCT have been reported for brofaromine,Citation56–Citation58 a drug that was never submitted for regulatory approval, and moclobemide,Citation50,Citation59–Citation63 which has been approved in many countries. Excluding brofaromine trials, the pooled OR for response to moclobemide is relatively modest compared with other antidepressant drugs (1.95; 95% CI 1.37–2.79). High heterogeneity (I2 = 69%) was noted in the analysis of this drug class. Exclusion of three studies of reversible selective inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (two brofaromine,Citation56,Citation58 one moclobemideCitation50) reduced the heterogeneity to 0%, but also reduced the pooled OR from 2.96 to 1.88.

Figure 3 Odds ratios and 95% CI for treatment response in randomized placebo-controlled trials for irreversible and reversible MAOIs. Response based on CGI for all studies except social phobia subscale of the Fear QuestionnaireCitation108 for Gelernter et al,Citation53 and the Hamilton Anxiety ScaleCitation109 for van Vliet et al.Citation56

Other antidepressants

There are open-label trials in social phobia with the tricyclic antidepressants, imipramineCitation64 and clomipramine,Citation65 but no RCT. Response to atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, was not different from placebo.Citation66 Two placebo-controlled RCT in social phobia have been reported for mirtazapine, an antagonist at 5HT2, 5HT3, and alpha2 adrenoceptors. One study showed a greater reduction in relevant outcome scales compared with placebo,Citation67 whereas the other showed no difference.Citation68 Both studies were relatively small (n = 30–33 per treatment arm), and both studies are likely to have been underpowered statistically. Nefazodone, an antagonist at 5HT1a and 5TH2a receptors, did not separate from placebo in a single large clinical trial.Citation69 The generally negative findings in social phobia with receptor antagonist antidepressants contrast with the robust positive findings for SSRIs and SNRIs.

Antiepileptic drugs

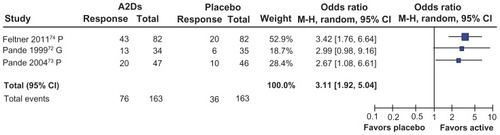

The use of antiepileptic drugs in social phobia has been extensively reviewed recently.Citation70 Only three antiepileptic drugs have been tested in RCT, and show distinct differences in efficacy. Gabapentin and pregabalin are both ligands at the alpha-2 delta site on voltage-gated calcium channels. Functionally, both drugs reduce the release of a range of excitatory neurotransmitters through binding to this site.Citation71 There are three positive RCT with alpha-2 delta ligandsCitation72–Citation74 (see ). The onset of anxiolytic effects is relatively rapid, occurring within the first week of treatment. The anxiolytic dose-response has only been formally assessed for pregabalin, and efficacy is only evident at the maximum dose (600 mg/day), but not at lower doses.Citation73,Citation74 This is in contrast with the effect of pregabalin in, eg, generalized anxiety disorder, where the anxiolytic dose-response is seen at much lower doses (150 mg/day).Citation75 There are no long-term treatment or relapse prevention data for alpha-2 delta ligands.

Figure 4 Odds ratios and 95% CI for treatment response in randomized placebo-controlled trials for the A2D ligands pregabalin (P) and gabapentin (G). Response based on CGI for all studies. Only the highest pregabalin doses are reported for Pande et alCitation73 and Feltner et al.Citation74

The only other antiepileptic drug assessed in RCT is levetiracetam, which has a complex pharmacology.Citation70 A large trial against placebo was negative.Citation76 The dose achieved in this trial (1180 mg/day) was at the low end of the dose range for epilepsy (1000–3000 mg/day). However, an earlier small RCT, in which higher levetiracetam doses were achieved, was also negative.Citation31

Open-label trials of valproate,Citation77 topiramate,Citation78 and tiagabineCitation79 have also been reported, all of which showed reductions in relevant social phobia rating scales. All studies were small (involving 17–54 subjects), and the magnitude of the change in symptom ratings was within the range that has been reported for placebo arms in other RCT.

Benzodiazepines

In clinical practice, there appears to be widespread use of benzodiazepines alone or in combination with antidepressants for social phobia,Citation80,Citation81 but clinical evidence to support this use is relatively limited. There are three placebo-controlled RCT, one each for clonazepam,Citation82 bromazepam,Citation83 and alprazolam.Citation53 All studies showed significantly greater improvement on a range of clinician-rating and self-rating scales compared with placebo. The mean doses used in these studies were generally modest (clonazepam 2.4 mg/day, bromazepam 21 mg/day, alprazolam 4.2 mg/day). The time course of response was only reported for the clonazepam study. Although there was a higher proportion of responders after one week of treatment (clonazepam 13.5%, placebo 0%), maximal response rates were noted after 6 weeks of treatment. Continuation of clonazepam treatment in treatment responders has been shown to decrease rates of relapse in social phobia compared with those switched to placebo.Citation84

Although the clinical practice of combining antidepressants and benzodiazepines appears to be common, it has been studied in only one small RCT. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam had a higher response rate (albeit not a statistically significant one) in an RCT in social phobia (79% versus 43%, P = 0.06) compared with paroxetine plus placebo.Citation85

Antipsychotics

Increased use of second-generation antipsychotic drugs for anxiety disorders has been identified in US prescribing data between 1996 and 2007.Citation86 The evidence base to support use in social phobia is very limited, with two small RCT. CGI response rates were not statistically significantly different between placebo and olanzapineCitation87 or quetiapine,Citation88 although the very small subject numbers (n = 7–10 subjects on active medication) suggest that neither trial was adequately powered statistically.

Other agents

Negative RCT outcomes have been reported for buspirone, a serotonin 1A partial agonist,Citation89 and for atenolol, a beta-adrenoceptor antagonist.Citation89

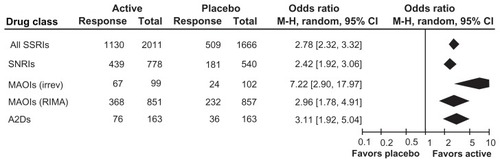

Summary of medication response

Placebo-controlled RCT have been reported for seven drug classes in social phobia. shows the comparative OR for treatment response for pooled results from five of these classes (insufficient data were available to include antipsychotic and benzodiazepine class data). The greatest treatment response was for the irreversible nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitor, phenelzine. It should be noted that this estimate is heavily influenced by data from one study,Citation50 and that relatively few patients were included in the four studies. Because of the risk of food and drug interactions, use of this class of drugs would not be first-line. The OR for reversible selective inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A is influenced by brofaromine data; brofaromine is not available to prescribe, and responses for moclobemide alone are more modest (OR 1.95; 95% CI 1.37–2.79). The other three drug classes have similar OR for treatment response, suggesting that differences in safety and tolerability profiles might influence selection between drug classes. Efficacy of the alpha-2 delta ligand, pregabalin, has only been reported at the 600 mg dose but not at lower doses; this higher dose is associated with high rates of dizziness and sedation. By default, this leaves SSRIs and the SNRI, venlafaxine, as first-line medication options for treatment of social phobia.

Figure 5 Odds ratios and 95% CI for treatment response in randomized placebo-controlled trials for five drug classes.

Psychological treatment trials

Over 30 randomized trials of psychological treatments have been conducted.Citation15,Citation16 Collectively these indicate that psychological interventions are effective in the treatment of social phobia. A critical issue is, however, effective relative to what? There is great variability in the nature of the control arm in psychological trials. These may include waitlist control, psychological placebo, drug, drug-placebo, or treatment as usual (which may or may not include drugs). Most studies have used wait-list control which is the least stringent test of effectiveness. Recent meta-analyses of psychological treatments have found fairly large effect sizes for psychological treatments compared with wait-list controls (Cohen’s d of 0.86), but smaller effect sizes (0.36–0.38) compared with placebo or treatment as usual.Citation15,Citation16

In addition to the question of whether psychological treatments are effective, a second question is which psychological treatment is optimal. Most studies, especially the earlier ones, have investigated variants or components of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The two meta-analyses cited earlierCitation15,Citation16 conducted subgroup analyses to determine whether inclusion of specific components of CBT, such as exposure, cognitive restructuring, relaxation, and social skills training makes a difference to treatment effectiveness. Neither study found significant differences in effectiveness as a function of inclusion versus noninclusion of any of these treatment components, nor did they find differences according to whether treatment was delivered individually or in group format.

This might suggest that it does not matter which type of psychological treatment is used, but recent trials of CBT against other evidence-based psychological treatments suggest otherwise. Koszycki et alCitation90 randomized participants with DSM-IV diagnoses of generalized social phobia to either group CBT or mindfulness-based stress reduction. Both groups improved, but the improvement with CBT was significantly greater. Borge et alCitation91 compared interpersonal therapy with CBT in a randomized trial conducted in a residential setting. Both treatments were equally effective, although the researchers noted that the CBT intervention was associated with less improvement compared with that reported by prior researchers. In a recent randomized controlled trial, Stangier et alCitation92 compared cognitive therapy with interpersonal psychotherapy. Both treatments were superior to wait-list control, but cognitive therapy was significantly more effective, a difference that was maintained at one-year follow-up. On the basis of this small number of studies, CBT or some variant of it remains the psychological treatment of choice, but interpersonal therapy or mindfulness-based therapies may be useful alternatives for patients who do not respond to CBT. A further important consideration is whether treatment effects endure. A meta-analysis of nine RCT of variants of CBT found significant effects at post-treatment (Cohen’s d of 0.68 across all trials) that were maintained at follow-up, with no drop in effect size (0.76).Citation16

The availability of psychological treatments such as CBT is often limited by funding or therapist constraints, so recent RCT that have found Internet CBT to be equally effective as the therapist-delivered version are a promising development.Citation93,Citation94 More research is required to determine whether Internet therapy can be as effective as the therapist-delivered version for the full spectrum of social phobia severity and complexity (in terms of comorbidity).

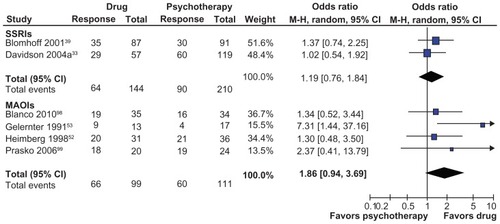

Medication versus psychological treatment

There are relatively few trials incorporating direct comparisons of medication with psychological treatments in social phobia. On the basis of the two trials shown in , there are no significant differences in effectiveness between SSRIs and psychological treatments. One additional trial of cognitive therapy versus fluoxetine,Citation95 which could not be included in the meta-analysis because the outcome analysis did not include responder data, found a significantly greater effectiveness of cognitive therapy. The meta-analysis of four monoamine oxidase inhibitor trials () suggests that these drugs may be superior to psychological treatments, but this result is not statistically significant.

Figure 6 Odds ratios and 95% CI for treatment response in randomized placebo-controlled trials for drug versus psychotherapy comparisons. Blomhoff et alCitation39 used exposure therapy; all other trials used cognitive behavioral therapy as the psychotherapy intervention. Response based on Clinical Global Impression for all studies except social phobia subscale of the Fear QuestionnaireCitation108 for Gelernter et al,Citation53 and the Social Anxiety ScaleCitation107 for Heimberg et al.Citation52

It is also important to consider how these treatments compare over the longer term. Three studiesCitation95–Citation97 have published follow-up data on outcomes after a treatment-free period. In all three trials, the psychological treatment showed greater maintenance of treatment gains or protection against relapse relative to the drug treatments.

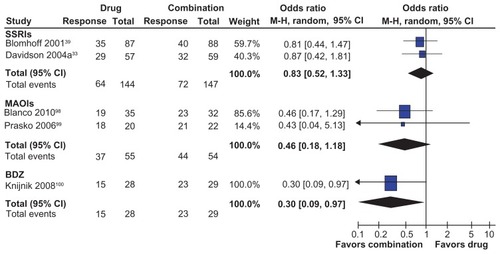

Medication versus combined medication-psychological treatment trials

There are five studies that have assessed treatment response in direct comparisons of medication with combined medication-psychological treatments in social phobia (two SSRI studies,Citation33,Citation39 two monoamine oxidase inhibitor studies,Citation98,Citation99 and one benzodiazepine studyCitation100 ). For response rates in the SSRI and monoamine oxidase inhibitor studies, there were nonsignificant trends in favor of combined medication-psychological treatments over medication alone. For the single benzodiazepine study, there was a statistically significant advantage in favor of combined treatment (). It should be noted that all studies were relatively small in size and thus may not have been adequately powered statistically.

Figure 7 Odds ratios and 95% CI for treatment response in randomized placebo-controlled trials for medication compared with combined medication-psychological treatment. Blomhoff et alCitation39 used exposure therapy; Knijnik et alCitation100 used psychodynamic group therapy; all other trials used cognitive behavioral therapy as the psychotherapy intervention. Response based on Clinical Global Impression for all studies.

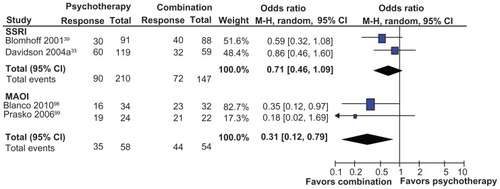

Psychological versus combined medication-psychological treatment trials

There are four studies that have assessed treatment response in direct comparisons of psychological treatment with combined medication-psychological treatments in social phobia (two SSRI studies,Citation33,Citation39 two monoamine oxidase inhibitor studiesCitation98,Citation99 ). For the pooled response rate in the SSRI studies, there was a nonsignificant trend in favor of combined medication-psychological treatments over psychological treatment alone. For the pooled response rate in the monoamine oxidase inhibitor studies, there was a significant trend in favour of combined medication-psychological treatments over psychological treatment alone (). It should be noted that all studies were relatively small in size and thus may not have been adequately powered statistically.

Figure 8 Odds ratios and 95% CI for treatment response in randomized placebo-controlled trials for psychological therapy compared with combined medication-psychological treatment. Blomhoff et alCitation39 used exposure therapy; all other trials used cognitive behavioral therapy as the psychotherapy intervention. Response based on Clinical Global Impression for all studies.

Discussion

All social phobia treatment guidelines recommend some combination of medication and psychological treatment for optimal management of patients with social phobia.Citation17,Citation18 Our meta-analysis findings are not inconsistent with this, although significant advantages of combination therapies are only evident with some drug classes and from a fairly small number of studies. For medications, the best initial choices would be SNRIs and SSRIs. For patients who do not respond to adequate doses/durations of dosing of either of these drug classes, monoamine oxidase inhibitors would be a relevant second-line choice. The older nonselective irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitor, phenelzine, is clearly more effective than the newer reversible selective agent, moclobemide, although its use is constrained by its well known food and drug interaction liabilities and side effect profile at higher doses. A number of other drug classes are commonly used for symptom relief in social phobia, and appear to be effective, although clinical trial data are limited. Benzodiazepine use should be limited to brief courses because of their dependence liability, relatively high levels of cognitive toxicity,Citation102 and potential for interfering with psychological treatment.Citation103 Low doses of quetiapine are also commonly used for anxiolysis,Citation104,Citation105 but the one RCT for this drug in social phobia was clearly underpowered to assess its effect.Citation88 Given that all benzodiazepines and most antipsychotic drugs have now become genericized, there is no commercial rationale for additional RCT in this area, and therefore it is unlikely that additional data will be generated to clarify how best to use these drugs in social phobia. The alpha-2-delta ligand, pregabalin, appears to have anxiolytic response rates comparable with SSRIs and SNRIs, but at doses of 600 mg/day where sedation and other side effects are likely to be reported, so its use should be reserved for refractory patients at this time. Combination drug treatment appears to be commonly used,Citation80,Citation81 but is not supported by RCT. The issue of how to treat patients who fail to respond to initial treatment is unresolved. A recent clinical guidance suggests a switching strategy, presumably based on data from the STAR*D studies,Citation106 but this is not supported by clinical trial data.

Of the psychotherapeutic approaches, CBT or some variant of it appears to be the most effective psychological treatment. It has the largest evidence base, and thus far it has emerged as superior in head-to-head comparisons with other recently developed, evidence-based treatments of mental disorders. CBT also appears to offer better protection from relapse at termination of treatment relative to drug treatments.

Limitations

Most treatment trials, particularly medication trials, only enroll a highly selected group of patients. Patients with comorbid disorders, such as current depression, alcohol misuse disorders, or suicidal ideation are usually excluded. As noted in the Introduction, comorbidity is the rule rather than the exception for patients with social phobia. Moreover, social phobia has a high degree of overlap with agoraphobia,Citation101 and can be accompanied by fears of public transport, meaning that some of the most severely affected will not seek treatment. This has implications for the generalizability of the findings reported here.

The effectiveness of combined treatments for social phobia highlights the problem that psychological treatments are not widely available in most countries, and social phobia is one of the most prevalent mental disorders, suggesting significant unmet need for the optimal treatment package for this debilitating disorder. This makes the emerging evidence of the efficacy of Internet-based CBT,Citation94 at least for uncomplicated presentations, a potentially important new opportunity to maximize the availability of combined treatments.

Disclosure

Within the last 3 years, JC has received a speaker’s honorarium from Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and PG has been on the scientific advisory boards for Forrest Pharmaceuticals, Demerx Pharmaceuticals, and Janssen-Cilag.

References

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders4th edWashington DCAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders3rd edWashington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association1980

- MageeWJEatonWWWittchenH-UMcGonagleKAKesslerRCAgoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity SurveyArch Gen Psychiatry19965321591688629891

- RuscioABrownTChiuWSareenJSteinMKesslerRSocial fears and social phobia in the USA: results from the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationPsychol Med2008381152817976249

- SteinMBKeanYMDisability and quality of life in social phobia: epidemiologic findingsAm J Psychiatry2000157101606161311007714

- KatzelnickDJKobakKADeLeireTImpact of generalized social anxiety disorder in managed careAm J Psychiatry2001158121999200711729016

- DavidsonJRHughesDGeorgeLKBlazerDGThe epidemiology of social phobia: findings from the Duke Epidemiological Catchment Area StudyPsychol Med19932337097188234577

- DeWitDJOgborneAOffordDMacDonaldKAntecedents of the risk of recovery from DSM-III-R social phobiaPsychol Med199929356958210405078

- ChartierMJHazenALSteinMBLifetime patterns of social phobia: a retrospective study of the course of social phobia in a nonclinical populationDepress Anxiety1998731131219656091

- SchneierFRJohnsonJHornigCDLiebowitzMRWeissmanMMSocial phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sampleArch Gen Psychiatry19924942822881558462

- SchneierFRFooseTEHasinDSSocial anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder co-morbidity in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related ConditionsPsychol Med201040697798820441690

- KesslerRCUstunTBThe WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental DisordersNew York, NYCambridge University Press2008

- SchneierFRPharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorderExpert Opin Pharmacother201112461562521241211

- RavindranLNSteinMBThe pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders: a review of progressJ Clin Psychiatry201071783985420667290

- AcarturkCCuijpersPvan StratenAde GraafRPsychological treatment of social anxiety disorder: a meta-analysisPsychol Med200939224125418507874

- PowersMBSigmarssonSEmmelkampPMGA meta-analytic review of psychological treatments for social anxiety disorderInt J Cogn Ther20081294113

- GanasenKIpserJSteinDAugmentation of cognitive behavioral therapy with pharmacotherapyPsychiatr Clin North Am201033368769920599140

- SteinDJBaldwinDSBandelowBA 2010 evidence-based algorithm for the pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorderCurr Psychiatry Rep201012547147720686872

- GuyWECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology – RevisedRockville, MDNational Institute of Mental Health1976

- BandelowBSeidler-BrandlerUBeckerAWedekindDRütherEMeta-analysis of randomized controlled comparisons of psychopharmacological and psychological treatments for anxiety disordersWorld J Biol Psychiatry20078317518717654408

- SteinDJIpserJvan BalkomAJPharmacotherapy for social anxiety disorderCochrane Database Syst Rev20004

- SteinMBLiebowitzMRLydiardRBPittsCDBushnellWGergelIParoxetine treatment of generalized social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a randomized controlled trialJAMA199828087087139728642

- LiebowitzMRGelenbergAJMunjackDVenlafaxine extended release vs placebo and paroxetine in social anxiety disorderArch Gen Psychiatry2005a62219019815699296

- LiebowitzMRSteinMBTancerMCarpenterDOakesRPittsCDA randomized, double-blind, fixed-dose comparison of paroxetine and placebo in treatment of generalized social anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychiatry2002631667411838629

- LepolaUBergtholdtBSt LambertJDavyKLRuggieroLControlled-release paroxetine in the treatment of patients with social anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200465222222915003077

- LaderMStenderKBürgerVNilREfficacy and tolerability of escitalopram in 12- and 24-week treatment of social anxiety disorder: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose studyDepress Anxiety200419424124815274173

- BaldwinDBobesJSteinDJScharwachterIFaureMParoxetine in social phobia/social anxiety disorder. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Paroxetine Study GroupBr J Psychiatry1999175212012610627793

- AllgulanderCManganoRZhangJEfficacy of venlafaxine ER in patients with social anxiety disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group comparison with paroxetineHum Psychopharmacol200419638739615303242

- AllgulanderCParoxetine in social anxiety disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled studyActa Psychiatr Scand1999100319319810493085

- KasperSSteinDJLoftHNilREscitalopram in the treatment of social anxiety disorderBr J Psychiatry2005186322222615738503

- ZhangWConnorKMDavidsonJRTLevetiracetam in social phobia: a placebo controlled pilot studyJ Psychopharmacol200519555155316166192

- KobakKAGreistJHJeffersonJWKatzelnickDJFluoxetine in social phobia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol200222325726212006895

- DavidsonJRTFoaEBHuppertJDFluoxetine, comprehensive cognitive behavioral therapy, and placebo in generalized social phobiaArch Gen Psychiatry2004a61101005101315466674

- van VlietIBoerJWestenbergHPsychopharmacological treatment of social phobia; a double blind placebo controlled study with fluvoxaminePsychopharmacology199411511281347862884

- SteinMBFyerAJDavidsonJRPollackMHWiitaBFluvoxamine treatment of social phobia (social anxiety disorder): a double-blind, placebo-controlled studyAm J Psychiatry1999156575676010327910

- DavidsonJYaryura-TobiasJDuPontRFluvoxamine-controlled release formulation for the treatment of generalized social anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol2004b24211812515206657

- Van AmeringenMALaneRMWalkerJRSertraline treatment of generalized social phobia: a 20-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyAm J Psychiatry2001158227528111156811

- LiebowitzMRDeMartinisNAWeihsKEfficacy of sertraline in severe generalized social anxiety disorder: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychiatry200364778579212934979

- BlomhoffSHaugTTHellstromKRandomised controlled general practice trial of sertraline, exposure therapy and combined treatment in generalised social phobiaBr J Psychiatry20011791233011435264

- MontgomerySANilRDurr-PalNLoftHBoulengerJPA 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of escitalopram for the prevention of generalized social anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200566101270127816259540

- SteinMBChartierMJHazenALParoxetine in the treatment of generalized social phobia: open-label treatment and double-blind placebo-controlled discontinuationJ Clin Psychopharmacol19961632182228784653

- SteinDJVersianiMHairTKumarREfficacy of paroxetine for relapse prevention in social anxiety disorder: a 24-week studyArch Gen Psychiatry200259121111111812470127

- WalkerJRVan AmeringenMASwinsonRPrevention of relapse in generalized social phobia: results of a 24-week study in responders to 20 weeks of sertraline treatmentJ Clin Psychopharmacol200020663664411106135

- DonovanMRGluePKolluriSEmirBComparative efficacy of antidepressants in preventing relapse in anxiety disorders – a meta-analysisJ Affective Dis20101231916

- SimonNMWorthingtonJJMoshierSJGeneralized social anxiety disorder: a preliminary randomized trial of increased dose to optimize responseCNS Spectr2010157436443

- SteinMBPollackMHBystritskyAKelseyJEManganoRMEfficacy of low and higher dose extended-release venlafaxine in generalized social anxiety disorder: a 6-month randomized controlled trialPsychopharmacology2005177328028815258718

- RickelsKManganoRKhanAA double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a flexible dose of venlafaxine ER in adult outpatients with generalized social anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol200424548849615349004

- LiebowitzMRManganoRMBradwejnJAsnisGSAD Study GroupA randomized controlled trial of venlafaxine extended release in generalized social anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychiatry2005b66223824715705011

- QuitkinFMStewartJWMcGrathPJTricamoEColumbia atypical depression: a subgroup of depressives with better response to MAOI than to tricyclic antidepressants or placeboBr J Psychiatry1993163Suppl 213034

- VersianiMNardiAMundimFAlvesALiebowitzMAmreinRPharmacotherapy of social phobia. A controlled study with moclobemide and phenelzineBr J Psychiatry199216133533601393304

- LiebowitzMRSchneierFCampeasRPhenelzine vs atenolol in social phobia: A placebo-controlled comparisonArch Gen Psychiatry19924942903001558463

- HeimbergRGLiebowitzMRHopeDACognitive behavioral group therapy vs phenelzine therapy for social phobia: 12-week outcomeArch Gen Psychiatry19985512113311419862558

- GelernterCSUhdeTWCimbolicPCognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a controlled studyArch Gen Psychiatry199148109389451929764

- VersianiMMundimFDNardiAELiebowitzMRTranylcypromine in social phobiaJ Clin Psychopharmacol1988842792833209719

- NuttDJGluePMonoamine oxidase inhibitors: rehabilitation from recent research?Br J Psychiatry19891542872912688773

- Van VlietIMden BoerJAWestenburgHGPsychopharmacological treatment of social phobia: clinical and biochemical effects of brofaromine, a selective MAO-A inhibitorEur Neuropsychopharmacol19922121291638170

- LottMGreistJHJeffersonJWBrofaromine for social phobia: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol19971742552609241003

- FahlénTNilssonHLBorgKHumbleMPauliUSocial phobia: the clinical efficacy and tolerability of the monoamine oxidase A and serotonin uptake inhibitor brofaromine: a double-blind placebo-controlled studyActa Psychiatr Scand19959253513588619339

- SteinDJCameronAAmreinRMoclobemide is effective and well tolerated in the long-term pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder with or without comorbid anxiety disorderInt Clin Psychopharmacol200217416117012131599

- SchneierFRGoetzDCampeasRFallonBMarshallRLiebowitzMRPlacebo-controlled trial of moclobemide in social phobiaBr J Psychiatry1998172170779534836

- OosterbaanDBvan BalkomAJLMSpinhovenPvan OppenPvan DyckRCognitive therapy versus moclobemide in social phobia: a controlled studyClin Psychol Psychother200184263273

- NoyesRJMorozGDavidsonJRTMoclobemide in social phobia: a controlled dose-response trialJ Clin Psychopharmacol19971742472549241002

- KatschnigHMoclobemide in social phobiaEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci1997247271809177952

- SimpsonHBSchneierFRCampeasRBImipramine in the treatment of social phobiaJ Clin Psychopharmacol19981821321359555598

- BeaumontGA large open multicentre trial of clomipramine (Anafranil) in the management of phobic disordersJ Int Med Res1977Suppl 5116123598600

- RavindranLNKimDSLetamendiAMSteinMBA randomized controlled trial of atomoxetine in generalized social anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychopharmacol200929656156419910721

- MuehlbacherMNickelMKNickelCMirtazapine treatment of social phobia in women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol200525658058316282842

- SchuttersSIJVan MegenHJGMVan VeenJFDenysDAJPWestenbergHGMMirtazapine in generalized social anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyInt Clin Psychopharmacol201025530230420715300

- Van AmeringenMManciniCOakmanJNefazodone in the treatment of generalized social phobia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trialJ Clin Psychiatry200768228829517335328

- MulaMPiniSCassanoGBThe role of anticonvulsant drugs in anxiety disorders: a critical review of the evidenceJ Clin Psychopharmacol200727326327217502773

- DooleyDJTaylorCPDonevanSFeltnerDCa2+ channel [alpha] 2 [delta] ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmissionTrends Pharmacol Sci2007282758217222465

- PandeACDavidsonJRTJeffersonJWTreatment of social phobia with gabapentin: a placebo-controlled studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol199919434134810440462

- PandeACFeltnerDEJeffersonJWEfficacy of the novel anxiolytic pregabalin in social anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled, multicenter studyJ Clin Psychopharmacol200424214114915206660

- FeltnerDELiu-DumawMSchweizerEBielskiREfficacy of pregabalin in generalized social anxiety disorder: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose studyInt Clin Psychopharmacol201126421322021368587

- GluePLoanAGaleCNew prospects for the drug treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic reviewCurr Drug Ther2010528694

- SteinMRavindranLSimonNLevetiracetam in generalized social anxiety disorder: a double-blind, randomized controlled trialJ Clin Psychiatry201071562763120021997

- KinrysGPollackMHSimonNMWorthingtonJJNardiAEVersianiMValproic acid for the treatment of social anxiety disorderInt Clin Psychopharmacol200318316917212702897

- Van AmeringenMManciniCPipeBOakmanJBennettMAn open trial of topiramate in the treatment of generalized social phobiaJ Clin Psychiatry200465121674167815641873

- DunlopBWPappLGarlowSJWeissPSKnightBTNinanPTTiagabine for social anxiety disorderHum Psychopharmacol200722424124417476705

- BenítezCIPSmithKVasileRGRendeREdelenMOKellerMBUse of benzodiazepines and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in middle-aged and older adults with anxiety disorders: a longitudinal and prospective studyAm J Geriatric Psych2008161513

- VasileRGBruceSEGoismanRMPaganoMKellerMBResults of a naturalistic longitudinal study of benzodiazepine and SSRI use in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder and social phobiaDepress Anxiety2005222596716094662

- DavidsonJRPottsNRichichiEKrishnanKRTreatment of social phobia with clonazepam and placeboJ Clin Psychopharmacol19931364234288120156

- VersianiMNardiAEFigueiraIMendlowiczMMarquesCDouble-blind placebo controlled trial with bromazepam in social phobiaJ Bras Psiquiatr1997463167171 Portuguese

- ConnorKMDavidsonJRTPottsNLSDiscontinuation of clonazepam in the treatment of social phobiaJ Clin Psychopharmacol19981853733789790154

- SeedatSSteinMBDouble-blind, placebo-controlled assessment of combined clonazepam with paroxetine compared with paroxetine monotherapy for generalized social anxiety disorderJ Clin Psychiatry200465224424815003080

- ComerJSMojtabaiROlfsonMNational trends in the antipsychotic treatment of psychiatric outpatients with anxiety disordersAm J Psychiatry2011168101057106521799067

- BarnettSDKramerMLCasatCDConnorKMDavidsonJRTEfficacy of olanzapine in social anxiety disorder: a pilot studyJ Psychopharmacol200216436536812503837

- VaishnaviSAlamySZhangWConnorKMDavidsonJRTQuetiapine as monotherapy for social anxiety disorder: a placebo-controlled studyProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20073171464146917698275

- DavidsonJPharmacotherapy of social phobiaActa Psychiatr Scand Suppl2003417657112950437

- KoszyckiDBengerMShlikJBradwejnJRandomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorderBehav Res Ther200745102518252617572382

- BorgeF-MHoffartASextonHClarkDMMarkowitzJCMcManusFResidential cognitive therapy versus residential interpersonal therapy for social phobia: a randomized clinical trialJ Anxiety Disord2008226991101018035519

- StangierUSchrammEHeidenreichTBergerMClarkDMCognitive therapy vs interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trialArch Gen Psychiatry201168769270021727253

- HedmanEAnderssonGLjótssonBInternet-based cognitive behavior therapy vs cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trialPloS One201163e1800121483704

- AndrewsGDaviesMTitovNEffectiveness randomized controlled trial of face to face versus Internet cognitive behaviour therapy for social phobiaAust N Z J Psychiatry201145433734021323490

- ClarkDMEhlersAMcManusFCognitive therapy versus fluoxetine in generalized social phobia: a randomized placebo-controlled trialJ Consult Clin Psychol20037161058106714622081

- LiebowitzMRHeimbergRGSchneierFRCognitive-behavioral group therapy versus phenelzine in social phobia: Long term outcomeDepress Anxiety1999103899810604081

- HaugTTBlomhoffSHellstromKExposure therapy and sertraline in social phobia: I-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trialBr J Psychiatry2003182431231812668406

- BlancoCHeimbergRGSchneierFRA placebo-controlled trial of phenelzine, cognitive behavioral group therapy, and their combination for social anxiety disorderArch Gen Psychiatry201067328629520194829

- PraskoJDockeryCHorácekJMoclobemide and cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of social phobia. A six-month controlled study and 24 months follow upNeuroendocrinol Lett200627447348116891998

- KnijnikDZBlancoCSalumGAA pilot study of clonazepam versus psychodynamic group therapy plus clonazepam in the treatment of generalized social anxiety disorderEur Psychiatry200823856757418774274

- ScottKMcGeeMOakley BrowneMWellsJEMental disorder comorbidity in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS)Aust N Z J Psychiatry2006401087588116959013

- HindmarchICognitive toxicity of pharmacotherapeutic agents used in social anxiety disorderInt J Clin Pract20096371085109419570125

- CurranVHBenzodiazepines, memory and mood: a reviewPsychopharmacology19911051181684055

- GluePGaleCOff-label use of quetiapine in New Zealand – a cause for concern?N Z Med J20111241336101321946739

- PhilipNSMelloKCarpenterLLTyrkaARPriceLHPatterns of quetiapine use in psychiatric inpatients: an examination of off-label useAnn Clin Psychiatry2008201152018297582

- RushATrivediMWisniewskiSAcute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR* D reportAm J Psychiatry2006163111905191717074942

- LiebowitzMRSocial phobiaMod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry1987221411732885745

- MarksIMMathewsAMBrief standard self-rating for phobic patientsBehav Res Ther1979173263267526242

- HamiltonMThe assessment of anxiety states by ratingBr J Med Psychol1959321505513638508