Abstract

Aim

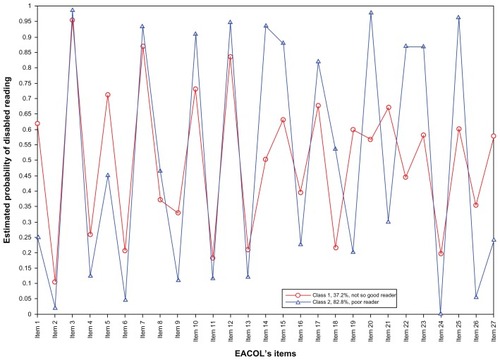

The study aimed to provide information about the concurrent and discriminant validation of the Scale of Evaluation of Reading Competence by the Teacher (EACOL), which is composed of 27 dichotomous items concerning reading aloud (17 items) and reading silently (10 items).

Samples

Three samples were used in this validation study. The first was composed of 335 students with an average age of 9.75 years (SD = 1.2) from Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais State), Brazil, where the full spectrum of reading ability was assessed. The second two samples were from São Paulo city (São Paulo State), Brazil, where only children with reading difficulties were recruited. The first São Paulo sample was labeled “SP-screening” and had n = 617, with a mean age of 9.8 years (SD = 1.0), and the other sample was labeled “SP-trial” and had n = 235, with a mean age of 9.15 years (SD = 0.05).

Methods

Results were obtained from a latent class analysis LCA, in which two latent groups were obtained as solutions, and were correlated with direct reading measures. Also, students’ scores on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale and on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire tested the discriminant validation.

Results

Latent groups of readers underlying the EACOL predicted all direct reading measures, while the same latent groups showed no association with behavior and intelligence assessments, giving concurrent and discriminant validity to EACOL, respectively.

Conclusion

EACOL is a reliable screening tool which can be used by a wide range of professionals for assessing reading skills.

Background

Evaluations and assessments by teachers are used to make educational decisions regarding students and to provide feedback to them, as well as to parents and school psychologists.Citation1,Citation2 Teachers’ reports can thus serve as a primary source of information in the educational settingCitation3 and play a very important role in assessment of emergent literacy.Citation4

The key issue that emerges in the educational context concerns the validity and reliability of teachers’ evaluations and the contrast between this type of indirect assessment and direct forms, involving the use of both behavioral methods and structured tasks, such as the number of correctly read words per minute from a list of real words.Citation4

A review of 16 studies concerned with the association between teachers’ evaluations and test scores obtained by students revealed a high level of validity for teachers’ assessment measures, but, at the same time, showed high variability in reliability. The range of correlation for the indirect comparisons (teachers were asked to use a rating of achievement in reading, math, social science, and language arts) was 0.28 to 0.86, whereas the direct tests (teachers were directly asked to estimate the achievement test performance of their students, for example, the number of problems on an achievement test that each student solved correctly) yielded a range from 0.48 to 0.92.Citation3

Twenty years after this seminal work, a study showed that the predictive validity of teachers’ reports for assessing emergent literacy skills of preschoolers was positive, with moderate to large effects between teachers’ evaluations and children’s performance.Citation5 However, there is a shortage of studies that provide good psychometric evidence for the tools that indirectly assess children’s reading performance, in spite of the increased demand for such instruments, especially ones that can effectively identify children at risk for future reading difficulties.Citation6

Recently, to this end, one study has shown that judgements of the teachers about their students’ progress that was based on a criterion-referenced assessment (children’s phonic skills and knowledge), was better than most formal tests in the identification of those who later experienced reading difficulties.Citation7

The early identification of these problems, through reliable measures with psychometric properties based on theoretical and empirical evidence, may play a key role in prevention. However, there is limited evidence about whether intervention can prevent the development of dyslexia and/or reading comprehension impairment in children early identified as at risk for reading difficulties.Citation8

In Brazil, there is a lack of tools that are based on teachers’ evaluations and that have good psychometric properties and theoretical foundations underlying the latent construct of reading competence. For example, one study found that teachers’ reports, although reliable as a whole, failed to identify specific reading difficulties in a number of children, and concluded that such conditions would only be detectable via functional analysis of the reading processes,Citation9 or by offering teachers a criterion-referenced instrument to help guide their judgment about the reading skills of students.Citation10,Citation11

EACOL

In order to implement this criterion, the authors developed the Scale of Evaluation of Reading Competence of Students by the Teacher (in Brazilian Portuguese: Escala de Avaliação de Competência em Leitura de Alunos pelo Professor [EACOL]), which evaluates reading aloud (RA) and silent reading (SR) in elementary-school children. The preliminary version of EACOL was tested by De Salles and ParenteCitation12 in 2007, during which they found significant associations between students’ performances in reading and writing words (as well as text comprehension) and teachers’ perceptions of these skills via the EACOL. The teacher, once assisted by a set of well-defined criteria, becomes then more capable of rating the reading and spelling performances of their students.

Development of the EACOL

To develop the EACOL, information such as the teacher’s experience, as well as a literature review about word recognition and comprehension, were considered. Elements that were thought to describe the RA and silent reading SR skills of elementary school children were obtained to formulate 57 items.Citation11 An operational definition of criteria for classification of readers into three categories was proposed: (1) good reader, (2) not-so-good reader, and (3) poor reader. In each category, items were subdivided into items about RA, and items about SR.

Ten independent experts (linguists and psychologists) who were specialists in psychological assessment and development of reading were asked to evaluate the relevance and applicability of items and criteria of reader ability. The experts were asked to grade each item’s pertinence from 1 to 5 (where 1 meant low and 5 very high relevance) to determine the importance of each criteria in defining the evaluation of reading competence by teachers. In addition, the experts were invited to suggest other relevant items and/or modifications to the list.

Following this procedure, the EACOL was designed to have two forms: A and B. Form A was developed to evaluate children’s reading skills in the final phase of literacy (approximately 7 years old). Form B was developed for children who are completely literate. Recently, the scale underwent a final adjustment.Citation13 In the current paper, we considered only form B (aimed at children from 8 to 10 years old).

Form B includes 27 items, 17 of which tap into the competence of reading aloud. Six of these items describe good reading ability, five items describe not-so-good reading ability, and six describe poor reading ability. The remaining ten items focus on SR; of these, four items describe good reading ability, three items describe not-so-good reading ability, and the remaining three items describe poor reading ability. The EACOL is provided in the .

The EACOL has not yet been applied in any language other than Brazilian Portuguese. The translation into English was carried out in the following three steps by the last author: translation from Portuguese to English, back-translation by a linguist, and correction and semantic adaptation where necessary.

The EACOL has not previously been submitted to a large-scale test of both concurrent and discriminant validity (the former is appropriate for test scores that will be employed in determining children’s current status with regard to reading skills; the latter is the evidence of low correlation between measures that are supposed to differ [ie, EACOL not being correlated to psychiatric symptoms or intelligence]);Citation14 as such, the objectives of this study were: (1) to identify subtypes of readers through use of the EACOL; (2) to describe the associations between the subtypes of readers found in this indirect measure of reading and various measures directly related and unrelated to reading; and (3) to verify whether the EACOL is sensitive to changes in instructions. Therefore, our hypotheses were: (1) If the EACOL is a useful screening tool for assessing reading skills of readers in grades two to four, latent groups of readers showing different levels of reading ability will be found; (2) if the students judged by the teachers using the EACOL as good, not-so-good, or poor readers show corresponding performance in direct measures of reading, this will be taken as concurrent validity for the instrument. Similarly, discriminant validity will be granted if no associations are found between the reading ability of the sample, and behavior and intelligence assessments; and (3) if the EACOL is sensitive to changes in instructions, the number of latent groups found will vary in accordance with the instructions given. That is, it was expected that a best-fit model with three latent groups of readers would be obtained when no specific direction in instruction was given to the teachers, and that lesser latent groups would emerge in situations in which teachers were explicitly asked to think of a particular type of reader, whether good or poor.

Methods

Sample recruitment

Three samples were used in this validation study: one from Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais State) and two from São Paulo city (São Paulo State).

The first sample, called the BH-sample, was the main reference sample. This was constituted by 335 children, students on average 9.75 years old (SD = 1.2) from second to fifth grade at five schools. Their teachers (n = 42), who agreed to participate through informed consent, were asked to complete the EACOL with the following instructions: “Please classify each of your students, according to the criterion presented. For each item please answer ‘Yes’ if it describes the reading ability of the student being evaluated and ‘No’ otherwise. Thank you for your collaboration.”

Of the São Paulo samples, the main one was constituted by 235 children aged 8 to 10 years old, from ten public schools located in impoverished areas in the outskirts of the city of São Paulo, which was part of a screening sample obtained from 617 children (mean = 9.8 years old [SD = 1.0]). The 48 teachers, from the second to fourth grades of these ten schools, were asked to complete the EACOL considering only the children with “a reading ability below the mean for the corresponding grade.” This instruction was given to screen eligible children to take part in a separate randomized clinical trial about the effectiveness of music education in the improvement of reading skills among children with reading difficulties (ClinicalTrial.gov: NCT01388881 and Research Ethic Committee from Federal University of São Paulo CEP 0433/10). The 617 children in the sample formed what we called the São Paulo Screening Sample (SP-screening).

On the basis of the SP-screening, trained psychologists then ranked children who had the worst EACOL scores to identify, per school, a minimum of 24 children with reading difficulties to participate in the randomized clinical trial about the effectiveness of music education. Since the ten schools had different numbers of enrolled children, four schools did not meet the criteria of 24 children per school. In the other six schools, where the numbers of eligible children exceeded 24, a minimum of 24 and a maximum of 27 children were randomly selected via a lottery. After having identified the eligible children, the research team contacted the parents through an introductory letter that provided a description of the objectives of the trial and the informed consent. In the case of interest and acceptance by the parents, the children were considered included as participants.

To avoid bias related to cognitive problems in the SP-trial due to the nature of the experimental randomized clinical trial, the included children were tested for nonverbal intellectual ability using the Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices;Citation15,Citation16 and children with scores below the 25th percentile were excluded. To avoid confounding due to contamination or overlap of interventions, parents were asked if their child was already receiving any regular hearing or speech therapy and/or music classes (such as private music classes, a social project involving musical learning, or other music schooling).

The total number of eligible children indicated by the teacher, selected by the psychologists as having the worst reading scores, and for whom parents returned authorization, was 240. Out of these, two children were excluded because they had a score below the 25th percentile, and three because they were already participating in social projects which involved musical learning and/or were under regular consultation with hearing and speech therapists. This left a sample of 235 children obtained from the SP-screening (38.08%), who were classified as not so good and poor readers, with average age 9.15 years (SD = 0.05). We called this group the São Paulo Trial Sample (SP-trial).

Both the BH-sample and the SP-screening were taken as reference groups. Only the SP-trial sample was submitted to the study of the external validation of the EACOL (described below).

This protocol for the randomized clinical trial (SP-screening and SP-trial) was submitted to and approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the Federal University (CEP0433/10) of São Paulo (UNIFESP). The protocol for BH-sample was approved by the Ethical Committee from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Process: n ETIC 347/04).

Measures

To evaluate the EACOL’s discriminant validity, we used Intelligence Quotient (IQ) total scoreCitation17 and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), which was completed by teachers.Citation18 The SDQ is a brief behavioral screening questionnaire comprising 25 items divided between 5 scales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relation problems, and prosocial behavior.

To test the concurrent validity of the EACOL, we selected a number of key variables to act as outcomes in the reading domain. These included:

accuracy in the word task (rate of correct real words read per minute);

accuracy in the nonword task (rate of correct nonwords read per minute); and

accuracy in the text task (rate of correct words read per minute).

The word and nonword tasksCitation19 consisted of a total of 88 words and 88 nonwords. The words varied in frequency levels of occurrence (high and low frequency words),Citation19 bidirectional regularity (regular and irregular words according to grapheme–phoneme/phoneme–grapheme correspondence),Citation20 and in length (short, medium, and long words, in terms of number of letters). The nonwords were built with the same Brazilian Portuguese orthographic structure and the same length of stimuli used in the word list. Here only the total number of correct words and nonwords read per minute in these tasks are considered; subgroup analysis related to regularity or irregularity or even word lengths were not conducted.

Psychometrically, the word and nonwords tasks showed excellent indices, presenting high correlation to each other (r = 0.92, P < 0.001), and moderately positive correlation with the Phonological Awareness TestCitation21 (raccuracy of word = 0.40 and raccuracy of nonword = 0.37). As expected, the general IQ was poorly related to word accuracy (r = 0.168, P = 0.01) and not correlated with nonword accuracy (r = 0.01, P = 0.131). Also, via Tobit regressions adjusted for the clusters of ten schools, schooling effects were observable in word accuracy through the academic years (ie, the higher education level, the better the achievement in the accuracy of words [third grade β = 6.62, P < 0.01; fourth grade β = 10.56, P < 0.01]) and in the accuracy of nonwords (third grade β = 4.45, P < 0.001; fourth grade β = 6.77, P < 0.001), corroborating for internal validation of both tasks.

Regarding the text that had to be read, a specific text was selected with consideration of the age of the child. The accuracy of text reading correlated highly with word accuracy (r = 0.916; P < 0.001) and with nonword accuracy (r = 0.873; P < 0.001). The children’s reading was audio-recorded for posttest analysis of accuracy.

Last, we included two covariates in the regressions models (described below). The first was visual acuity (age-appropriate) via Snellen chart, under conditions of monocular viewing, conducted by a technician in ophthalmology. The children were classified as having visual alterations or not. The second was the Simplified Central Auditory Assessment,Citation22 conducted by a hearing and speech pathologist, which tested the elicitation of the auropalpebral reflex through instrumental sounds; sound location in five directions; sequential verbal memory for sounds with three and four syllables; and sequential nonverbal memory with three and four percussion musical instruments. The children were classified as having problems in central auditory processing or not.

Statistical modeling

To verify the number of latent groups in the three samples (BH-sample, SP-screening and SP-trial), we used latent classes analysis (LCA) on the 27 dichotomous items in the EACOL. The LCA is a form of cluster analysis initially introduced by Lazarsfeld and Henry in 1968.Citation23 It is the most commonly applied latent structure model for categorical data,Citation24 allowing the specification of statistical distributions through a model-based method, which differs from methods that apply arbitrary distance metrics to group individuals based on their similarity (for example, K-means clustering).Citation25 In the LCA, unlike K-means clustering, a statistical model is built for the population from which the data sample was obtained.Citation26

To compare LCA models with different numbers of latent classes, we used the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), in which small values correspond to better fit, as well as the sample size-adjusted BIC (ssaBIC). The classification quality of the model was evaluated with the entropy criterion, in which the values range from 0 to 1, where values close to 1 indicate good classification. All LCA were conducted via Mplus version 6.12 (Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA).Citation27

Both samples from SP were used to test whether the types of instructions that were given to the teachers would change the number of latent classes in comparison to the BH reference sample. Both concurrent and discriminant validity were assessed using a regressions model STATA version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), considering robust standard errors to adjust for the cluster structure. Covariates such as age, sex, grade, and visual acuity and central auditory processing were considered in the regression models. It is important to emphasize that distributions, kurtosis, and skewness of the outcomes and covariates were checked to choose the better regression model. To optimize the visualization of the estimated probabilities as results of LCA, all “positive” EACOL items (eg, “reads with intonation compatible with punctuation marks;” “quickly reads ‘new’ and invented words;” “quickly reads ‘known’ and ‘little- known’ words”) were reverse-scored for ease of interpretation. The recoded items were 3, 7, 12, 14, 15, 17, 20, 22, 23, and 25.

Results

Results of the LCA

The LCA of BH suggested a good fit-model with three classes, while a two-class model for SP-screening and SP-trial was confirmed (–).

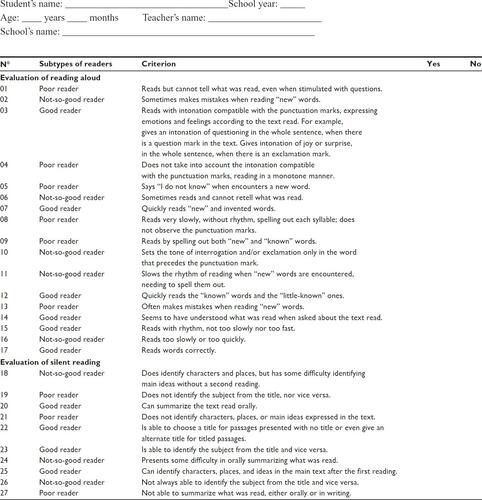

Figure 1 Latent classes analysis for BH-sample.

To establish which class corresponds to which category of reader, it is necessary to refer to –, where the estimated probability axis has a scale from 0 to 1. The former indicates good reading ability, while the latter represents reading disability.

In the BH-sample, a clear three-class solution is supported, considering empirical and theoretical elements.

For the SP-screening and SP-trial samples, the parametric bootstrap P-values for the likelihood ratio X2 goodness of fit test returned values of P < 0.001 for the one-, two-, three-, and four-class models, but only the two-class solutions had theoretical and empirical plausibility. Taking Akaike information criterion, BIC, ssaBIC, and entropy results together with the theoretical information about the EACOL and the principle of parsimony, the two-latent-class model was deemed as the most appropriate to describe the data. The model identifies children groups with different patterns of reported reading in both these samples from São Paulo ().

Table 1 Latent class analysis results

Description of typological (latent) classification

BH-sample

In this reference sample, a three-class model provided the optimal solution, as observed in . Class 1 had model-based prevalence of 26.9% of the sample, class 2 had 12.1%, and class 3 was the most prevalent at 61.1%. Class 2 is represented by superior marginal probabilities (close to 1), class 3 by inferior marginal probabilities (close to 0), and class 1 is represented by the medial line where nonmarginal probabilities occur (the majority of probabilities are centered between 0.25 and 0.75). There are three distinct lines which have a small amount of overlap and only two crossed trajectories (items 16 and 17). In the BH, we referred to class 3 as “good readers,” class 1 as “not-so-good readers,” and class 2 as “poor readers.”

São Paulo samples

The latent structure of the classes in both samples was similar, considering the distribution of estimated probabilities through the 27 items, the number of classes, and the proportion between the percentages of children in each class.

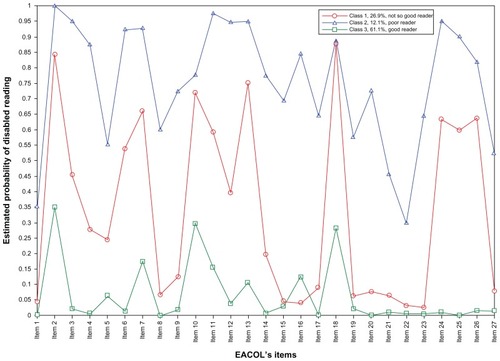

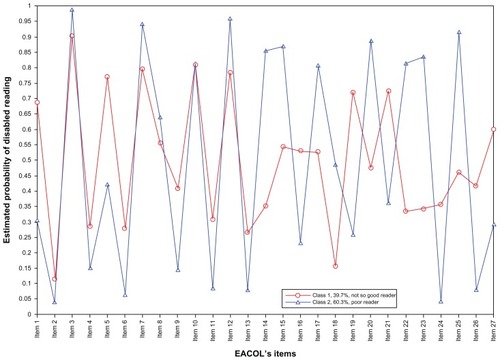

In the graph of the estimated probabilities for SP-screening sample (), class 1 comprised 39.7% of the sample. In the case of the SP-trial (), class 1 had a model-based prevalence estimate of 37.2%, and included children with median probabilities (from 0.3 to 0.7) in the majority of items reported. We referred to this class as “not-so-good readers.”

Figure 2 Latent classes analysis for the São Paulo Screening Sample.

Figure 3 Latent classes analysis for the São Paulo Trial Sample.

Class 2 in the SP-trial had a model-based prevalence of 62.8%, and included children who had a marginal value (P > 0.8) probability, indicating that eleven out of the 27 EACOL items fit the “poor readers” class. The highest probabilities were observed in the following items: “can summarize the text read orally (item 20);” “can identify characters, places, and ideas in the main text after the first reading (item 25);” and “quickly reads ‘known’ words and ‘little-known’ ones (item 12).” In the SP-screening sample, the percentage of the children in class 2 was 60.3%.

The two samples from São Paulo returned similar prevalence for the two latent classes. In addition, it is possible to observe that some items have results with “crossed trends” or even “overlapped trends.” This means that these items are not good for discriminating classes and, therefore, could be omitted or excluded in later studies.

With regard to both reading domains (AR and SR) separately, while in BH-sample, RA (from item 1 to item 17) works better, in the samples from São Paulo, SR domain (from item 18 to item 27) better distinguishes the “poor reader” from the “not-so-good” reader class.

Discriminant and concurrent validity

IQ and SDQ

To test EACOL’S discriminant validity, we used the general IQ and total difficulties children’s score in the SDQ as a dependent variable against the same exploratory variable that was used in the above-cited model. We did not observe an association between the latent classes and IQ (β = 6.55, P > 0.05) and children’s total difficulties score measured by the SDQ (β = 1.12, P > 0.05), as observed in the , when controlled by age, sex, grade, and school as a cluster unity.

Table 2 Values for regression coefficients with its respective robust standard error, P-value and 95% confidence interval for variables of concurrent and discriminant validity

Reading outcomes

In the regression analyses, the class latent typology had a significant negative association with the three reading measures, controlling for age, grade, sex, and visual acuity and processing auditory status; also the cluster design was considered and consequently, robust standard errors were generated. Results are described in .

Being a member of the poor-reader class has major negative impact in all reading outcomes, showing that this group has more reading difficulties than the not-so-good readers. For the accuracy of words (β = −11.12, P < 0.0001; in other words, a significant difference of 11 correctly read words per minute between both latent groups of readers) and accuracy of nonwords (β = −6.50 P < 0.001), we used Tobit regression due to the floor effects in both continuous outcomes (children who read zero words/nonwords correctly) and, therefore, we specified one left-censoring limit of 1 correctly read word per minute. For the accuracy of text reading (β = −11.27, P < 0.01), a linear-regression model was used, showing that there is an effect of being class 1 or 2 on the outcome. More precisely, comparing not so good readers and poor readers, we expected that the worst indicators of reading would be achieved from poor readers (class 2).

Discussion

The present study explored the predictive ability of indirect measures of teachers’ reports of children’s reading ability. The latent groups of readers predicted direct measures of reading abilities, particularly in the area of decoding of isolated words (represented here as accuracy of word and nonword reading) and words in context (represented as the accuracy of reading text). Considering the SP-trial, the poor-reader latent group correctly read 6.50 nonwords less per minute than did the not-so-good readers. Also, in the other reading measures, the differences between both groups are statistically significant: the poor-reader latent group’s performance was worse than that of the not-so-good-reader group regarding accuracy of reading both isolated words and words in context (difference of 11.12 and 11.27 correctly read words per minute, respectively) (). These results are evidence of the concurrent validity of the EACOL.

We also evaluated the extent to which the instructions given to the teachers could accurately affect the identification of the latent groups of readers.

Major findings and clinical implications

The BH sample returned a three-class model while SP samples returned a two-class model due to the instructions that were given to the teachers. As a consequence, the number of returned classes must be different, giving evidence for the concurrent validity of the EACOL. Considering that in the BH-sample the EACOL covered the full spectrum of the reading abilities (ie, no discriminative instruction was given to the teachers), the BH-sample prevalence results may suggest either that the teacher has a tendency to overestimate the children’s reading ability, or that perhaps teachers tend to or even prefer to answer about children who have nonspecific academic difficulties of some sort. Since the EACOL inquires about specific characteristics of children’s reading, which normally are observable one-by-one, it is necessary to have a proximal contact with the child, especially to evaluate items related to silent reading, which showed better discrimination in SP-sample (ie, samples of children with reading difficulty). Therefore, when no specification of the type of reading ability of the participants is requested, teachers may tend to complete the EACOL considering predominantly the children with good and not so good reading abilities (the major prevalence groups in the BH-sample).

We expected to observe proportions among the three classes to be similar to the normal curve, with the majority of the children categorized around the mean (corresponding to the average reader, here the “not-so-good reader”) and the minority (both good and poor readers) placed with regard to the marginal probabilities, closer to 0 and closer to 1, respectively.

The BH sample returned a three-class model, while SP samples returned a two-class model, due to the instructions given to the teachers. As a consequence, the number of returned classes must be different, giving evidence for the concurrent validity of EACOL.

As can be seen in , the entropy values (ie, how well the classes are distinguished from each other) in both samples from São Paulo are lower than in the sample from BH. This could refer to the difficulty of teachers in evaluating children due to the instructions, especially those who had reading difficulties. Taking into consideration the BH-sample, a three-class solution was achieved and only two items had “crossed values.” Therefore, when no instruction is given to the teachers, distinctions amongst the three reading categories is more precise than when a restriction is given.

Taking the two domains of the scale RA and SR into account, some details could be addressed about the 27 items. In the cases of SP-trial and SP-screening, it is possible to observe in the graphs of estimated probabilities, a major overlapping in the RA domain (ie, represented by two lines closer or with the same trajectory), whereas in the SR domain the two lines do not overlap.

In the BH-sample, in which the good readers and not-so-good readers (: classes 3 and 1, respectively) have very close probabilities (P < 0.1), taking into account five of the ten items (items 19, 20, 21, 22, 23), RA was found to work better than SR. In RA, the item 15 (“reads with rhythm, not too slowly nor too quickly”) did not have the probability to discriminate the classes of “good reader” and “not-so-good reader,” because there was an overlap between two classes in the same probability. With the exception of this item, RA seems to better differentiate the classes when no direction is given to teachers, probably because in the school context it might be easier to observe difficulties in reading aloud than in silent reading (as evaluation of this latter type of reading is often obtained “head-to-head”), through specific investigation and inquiry about the students’ comprehension capacity (such as his/her ability to use knowledge of world to make inferences and to monitor the understanding of what is being read).Citation28 On the other hand, when teachers were required to think about the children with reading difficulties, SR became a better measure by which to distinguish not-so-good readers from poor readers, since, in this condition, the overlapping of trajectories among the items was less frequent. With respect to discriminant validity, the latent groups in SP-trial did not predict the total score in the Wechsler Intelligence Scale, as found also by Hatcher and Hulme,Citation29 or SDQ as expected, showing that both of these domains were not associated with reading skills. More specifically, children’s behavioral characteristics evaluated via SDQ were not taken into account in teachers’ evaluations of children’s reading. In other words, teachers were capable of distinguishing the presence of behavioral problems from reading difficulties, indicating that they evaluated both theoretical constructs domains independently. This is in disagreement with the finding that the teachers’ perceptions of their students’ behavior constituted a significant component of the judgments made about their students’ scholastic achievements.Citation30

Therefore, this study found evidence that the EACOL is a reliable instrument by which to assess reading via teachers’ judgment. Since it is simple and easy to administer, it is an important tool to help a wide range of professionals (eg, health professionals who work with children, teachers and educators, and researchers).

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq – grant No 482321/2010-5) and the Instituto ABCD, which is a nongovernmental organization that supports research about dyslexia in Brazil.

Disclosure

JJM, HCM, GBP, and CRM conducted a randomized clinical trial about the effectiveness of music education among children with reading difficulties. EACOL was used as a screening tool in selected children with reading difficulties. CRBA recently received a grant (São Paulo Research Foundation grant number 2011/11369-0) to develop a tool to evaluate reading comprehension among schoolchildren. HCM received a PhD scholarship from CNPq and CAPES Foundation, an agency under the Ministry of Education of Brazil, in order to conduct part of his doctoral research as a visiting graduate student at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

References

- ElliottSNGreshamFMFreemanTMcCloskeyGTeacher and observer ratings of children’s social skills: validation of the Social Skills Rating ScalesJ Psychoeduc Assess198862152161

- GerberMMSemmelMITeacher as imperfect test: reconceptualizing the referral processEduc Psychol1984193137148

- HogeRDColadarciTTeacher-based judgments of academic achievement: a review of literatureRev Educ ResFal1989593297313

- SalingerTAssessing the literacy of young children: the case for multiple forms of evidenceNeumanSBDickinsonDKHandbook of Early Literacy ResearchNew YorkGuilford Press20021390418

- CabellSQJusticeLMZuckerTAKildayCRValidity of teacher report for assessing the emergent literacy skills of at-risk preschoolersLang Speech Hear Serv Sch200940216117319336834

- SchatschneiderCPetscherYWilliamsKMHow to evaluate a screening process: the vocabulary of screening and what educators need to knowJusticeLMVukelichCAchieving Excellence in Preschool Literacy InstructionNew YorkGuilford Press2008304316

- SnowlingMJDuffFPetrouASchiffeldrinJBaileyAMIdentification of children at risk of dyslexia: the validity of teacher judgements using ‘Phonic Phases’J Res Read52011342157170

- SnowlingMJHulmeCAnnual research review: the nature and classification of reading disorders – a commentary on proposals for DSM-5J Child Psychol Psychiatry201253559360722141434

- PinheiroAMVHeterogeneidade entre leitores julgados competentes pelas professorasHeterogeneity among readers judged as competent by teachersPsicol Refl Crít2001143537551 Brazilian Portuguese

- PinheiroAMVCostaAEBOs passos da construção da Escala de Avaliação de Competência de Leitura de alunos pelo professor – EACOLThe development of the Scale of Evaluation of Reading Competence by the Teacher – EACOLPaper presented at: VII Internacional de Investigação em Leitura, Literatura Infantil e Ilustração Meeting2012 Sep 17–19Braga, Lisbon Portuguese

- PinheiroAMVCostaAEBEscala de avaliação de competência em leitura pelo professorScale of Evaluation of Reading Competency by the TeacherPaper presented at: VII Encontro Mineiro de Avaliação Psicológica2005Belo Horizonte, Brazil Brazilian Portuguese

- De SallesJFParenteMAMPRelação entre desempenho infantil em linguagem escrita e percepção do professorChildren’s performance in written language and perception of teacherCad Pesqui200737132687709 Brazilian Portuguese

- PinheiroAMVValidação e Estabelecimento de Normas de Uma Prova Computadorizada de Reconhecimento de Palavras Para CriançasBelo HorizonteFederal University of Minas Gerais2012 SHA – APQ-01914–09

- UrbinaSEssentials of Psychological TestingHobokenJohn Wiley & Sons2004

- PasqualiLWechslerSBensusanEMatrizes Progressivas do Raven Infantil: um estudo de validação para o BrasilRaven’s Colored Progressive Matrices for Children: a validation study for BrazilAval Psicol20021295110 Brazilian Portuguese

- RavenJRaven’s Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary ScalesLondonHK Lewis1986

- WechslerDWISC-III: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for ChildrenSan AntonioThe Psychological Corporation1991

- GoodmanRThe Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research noteJ Child Psychol Psychiatry19973855815869255702

- PinheiroAMVContagem de Frequência de Ocorrência de Palavras Expostas a Crianças na Faixa Pré-escolar e Séries Iniciais do 1° GrauCount Frequency of Word Occurrence Amongst Preschoolers and Elementary School ChildrenSao Paulo (SP)Associação Brasileira de Dislexia1996 Brazilian Portuguese

- PinheiroAMVAnexo 2Sim-SimIViannaFLPara a Avaliação do Desempenho de LeituraReading Achievement Performance EvaluationLisbonGabinete de Estatística e Planeamento da Educação2007121131 Brazilian Portuguese

- CapovillaAGSCapovillaFCProva de consciência fonológica: desenvolvimento de dez habilidades da pré-escola à segunda sériePhonological Awareness Test: development of ten abilities from preschool to third gradeTemas Desenvolv19987371420 Brazilian Portuguese

- LazarsfeldPFHenryNWLatent Structure AnalysisBostonHoughton Mifflin1968

- EngelmannLFerreiraMIDCAvaliação do processamento auditivo em crianças com dificuldades de aprendizagemAuditory processing evaluation in children with learning difficultiesRev Soc Bras Fonoaudiol20091416974 Brazilian Portuguese

- CloggCCLatent Class ModelsNew YorkPlenum1995

- EverittBSHandDJFinite mixture distributionsCoxDRIshamNKeidingTMonographs on Applied Probability and StatisticsLondonChapman and Hall1981

- MagidsonJVermuntJLatent class models for clustering: A comparison with K-meansCanadian Journal of Marketing Research20022013744

- MuthénLMuthénBStatistical Analysis with Latent Variables: User’s Guide4th edLos AngelesMuthén & Muthén19982011

- RickettsJResearch review: reading comprehension in developmental disorders of language and communicationJf Child Psychol Psychiatry2011521111111123

- HatcherPJHulmeCPhonemes, rhymes, and intelligence as predictors of children’s responsiveness to remedial reading instruction: evidence from a longitudinal intervention studyJ Exp Child Psychol19997221301539927526

- BennettREGottesmanRLRockDACerulloFInfluence of behavior perceptions and gender on teachers’ judgments of students’ academic skillJ Educ Psychol1993852347356