Abstract

This article presents a current review of the risk of physical and psychological injury associated with participation in elite youth sport, and suggests strategies to ensure the physical and emotional health of these young athletes. Although there is lack of epidemiological data, especially with regard to psychological injury, preliminary data suggest that the risk of injury is high in this population. While there is lack of incident and follow-up data, there is also concern regarding burnout, disordered eating, and the long-term consequences of injury. Modifiable injury risk factors identified include postural control, competition anxiety, life events, previous injury, and volume of training. There are presently no studies designed to determine the effectiveness of injury prevention measures in elite youth sports. However, there is adequate evidence arising from injury prevention studies of youth sports participants – including neuromuscular training, protective equipment, mental training to enhance self-esteem, and sport rules modification – to prevent injuries in elite youth sports settings. Although not tested, psychosocial prevention strategies such as adoption of task-oriented coping mechanisms, autonomous support from parents, and a proactive organizational approach also show promise in injury prevention.

Introduction

Participation in youth sports is increasingly popular and widespread internationally. Trends over recent decades include increased numbers of participants in some sports, particularly girls, increased duration and intensity of training, earlier specialization and year-round training, and increased difficulty of skills practiced.Citation1 In the United States, for example, more than 38 million children and adolescents participate in organized sports each year.Citation2 It is not uncommon for young talented athletes from an age of 12 to 13 years to train 15–20 hours per week at regional training centers in tennis or gymnastics, or for youngsters as young as 6–8 years of age to play organized hockey or soccer and travel with select teams to other towns and communities to compete against other teams of similar caliber.

Sport is by its very nature competitive and even during youth it is performed at different levels, with elite young athletes at the top of the performance pyramid. The elite young athlete is one who has superior athletic talent, undergoes specialized training, receives expert coaching, and is exposed to early competition.Citation3 At the elite level, national and international sporting federations have organized youth competitions in various age classes for athletes competing ranging from as low as under-13 up to under-21 depending on the sport.Citation4 These competitions also represent important showgrounds where, in some sports, young talented athletes are identified for a future professional career.Citation5

Since 1991, the European Youth Olympic Festival (EYOF), a biennial multisport event for youth athletes, has been sponsored by the association of European Olympic Committees. In recent years, the International Olympic Committee created a more extensive international sporting event for talented young athletes from all over the world. Just like the Olympic Games, the Youth Olympic Games (YOG) are held every 4 years. The first Summer YOG was held in Singapore from 14 to 26 August 2010, and the first Winter YOG was held in Innsbruck, Austria, from 13 to 22 January 2012.Citation6 The YOG aim to bring together talented young athletes from ages 15 to 18 from around the world. The Summer YOG regularly feature over 3,500 athletes and are held over a 12-day period, and the Winter YOG feature over 1,100 athletes and last 10 days.Citation6 In addition to all of the sports typically included in the Olympics, the YOG have also showcased several adventure and extreme sports that involve highly specialized gear or spectacular stunts and are well known for their inclusion of elements of real or perceived risk. For example, skateboarding, in-line skating, and sport climbing were showcased in the 2014 YOG in Nanjing. Bicycle motocross and mountain biking were also included in the Nanjing YOG.Citation7

Engaging in sports activities at a young age has important physical health benefits, but also involves risk of injury. This would seem to be particularly true at the elite level given the intensive training programs and high-frequency participation in sports events.Citation8 Inevitably, increased participation is associated with an increased risk of physical injury, or even sudden death.Citation8 The young athlete may also incur psychological injury as a consequence of parents who exercise excessive pressure to perform or do not protect their children from harmful relationships, from emotionally abusive coaching behaviors, or from bullying and hazing behaviors from teammates.Citation9 In addition to the immediate health care costs, these injuries may have long-term consequences on physical and psychological health, resulting in reduced levels of physical activity and, ultimately, reduction in wellness.Citation9–Citation11 Although it is impossible to eliminate all injuries, attempts to reduce risk of injury are obviously warranted.

The purpose of this article is to provide a current review of risks related to physical and psychological injury that may be encountered by elite youth athletes and to discuss strategies designed to minimize or eliminate these risks. Relevant research arising from youth athletes and elite-level adult athletes is included to augment the limited research related to elite youth athletes, especially with regard to psychological injury. Recommendations are made for further research that focuses on the physical and emotional health of young athletes.

Physical/physiological risks for injury in elite youth athletes

Challenges to physical health

Growth and maturation-related factors

Elite youth athletes may be particularly vulnerable to injury due to such growth-related factors as the adolescent growth spurt,Citation12,Citation13 susceptibility to growth plate injury,Citation13,Citation14 age- and maturity-associated variation,Citation14,Citation15 longer recovery and differing physiological response after concussion,Citation16,Citation17 and nonlinearity of growth.Citation18,Citation19 They might also be at risk because of immature or underdeveloped coordination, skills, and perception.Citation20 Concern has also been raised regarding the young female athlete who may be at increased risk of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries due to such factors as anatomy, hormones and menstrual cycle, neuromuscular characteristics, muscle strength, and flexibility.Citation21 The more frequent and intensive training and competition of young elite athletes now may create conditions under which these potential risk factors can more readily exert their influence.

Risk of injury

Recent data suggest that the risk of sport injury among elite youth athletes is high.Citation22 If one adopts the predefined age range of 14–18 years, with “elite” reflecting competition at the national or international level,Citation4 then a search of the literature reveals three studies presenting exposure-based (per 1,000 hours) seasonal injury data on adolescent elite soccer athletes.Citation23–Citation25 Training injury rates ranged from 1.4 to 4.6 injuries/1,000 hours, while competition rates were higher, ranging from 10.5 to 22.4 injuries per 1,000 hours. Injury rates in badminton were 2.8 for practice and 5.9 for games.Citation26

Injury rates for U17 and U19 European and World soccer championships were generally higher than those reported for seasonal studies.Citation27–Citation30 Training injury rates at these championships ranged from 1.1 to 7.4 injuries per 1,000 hours.Citation27,Citation28 In contrast, competition injury rates ranged from 11.7 to 88.1 injuries per 1,000 hours.Citation27–Citation30 Injury rates in soccer were generally higher for females than males in both seasonal and tournament studies.

Several studies reported medical encounters for elite youth athletes at world and national championships. Caine and NassarCitation31 summarized results of injuries treated by the USA Gymnastics Medical Staff during the 2002–2004 Gymnastics National Women’s Gymnastics Championship. Depending on year, from 44.9% to 71.7% of registered gymnasts were treated for acute and/or overuse conditions. Overall, 16 treated conditions (11%) required surgery. During the 2014 YOG, there were 346 total medical encounters among 54 of the 94 registered US athletes (57.4%), for a rate of 3.7 medical encounters per athlete. No surgeries were required.Citation32

Ruedl et alCitation33 reported clinical incidence of injury incurred by young athletes participating in the first Winter YOG 2012 in Innsbruck, Austria. Among the 1,021 registered athletes, a total of 111 injuries were incurred, resulting in a reported incidence of 108.7 injuries per 1,000 registered athletes. Similarly, van Beijsterveld et alCitation34 reported clinical incidence of injuries sustained during the 2013 Summer EYOF. Among the 2,072 registered athletes, a total of 207 injuries were incurred, resulting in a reported incidence of 91.1 injuries per 1,000 athletes. During the 2015 Winter EYOF, 899 registered athletes sustained 38 injuries for a rate of 42.3 injuries per 1,000 athletes.Citation35

Unfortunately, clinical incidence does not account for the potential variance in exposure among participants and sports for risk for injury. Additionally, tournament rates may not be representative of the nature and incidence of injuries incurred by athletes during training and competition throughout the year, especially with regard to overuse injuries.

Risk factors for injury

There is little knowledge on injury risk factors specifically pertaining to elite youth athletes. However, analysis of sports injury risk factors in child and adolescent sport has identified a number of significant predictors of injury that may inform development and evaluation of injury prevention programs relative to the elite youth sport participant population. These include age/level of play,Citation36–Citation41 adolescent growth spurt,Citation42–Citation45 postural control,Citation46–Citation49 biologic maturity,Citation50–Citation52 body size,Citation53–Citation55 sex,Citation56–Citation59 previous injury,Citation35,Citation40,Citation60–Citation62 rules regarding body-checking in ice hockey,Citation63–Citation65 volume of training,Citation66–Citation71 and fatigue.Citation72–Citation75 There is also preliminary evidence that menstrual irregularity and low-energy availability may relate to increased risk of injury in youth athletes.Citation60,Citation76,Citation77

Results of risk factor analyses in youth sports may suffer from one or more methodological limitations (eg, small-scale, short-term, inconsistent standards for determining exposure) and should, therefore, be viewed as initial steps in the important search for predictor variables that may provide interesting characteristics for manipulation in studies of elite youth athletes.Citation78,Citation79 Modifiable risk factors such as postural control, previous injury, volume of training, and fatigue may have particular application for elite youth athletes, given the rigor and volume of their training and competitive regimens.

Nutrition

A lack of research exists regarding the elite youth athlete and nutrition related to energy intake to support growth and, by extension, prevent injury. Most research on nutrition and elite youth athletes is focused on eating disorders. Energy intake is important for performance; however, elite athletes are at risk for developing eating disorders.Citation80 On the basis of the literature of young adults, higher rates of eating disorders are found in female elite athletes (20%) compared to nonathletes (9%).Citation81 Typically, male athletes are focused on weight gain and a muscular physique, whereas female athletes are pressurized to be thin, particularly in sports where having a small body size is beneficial for performance.Citation82–Citation84 Female athletes are at risk for failing to meet their estimated energy needs regarding their dietary intake.Citation82 Additionally, female athletes suffer from cultural and social pressure to be thin and lean, which is more common in sports where body weight and shape affects performance.Citation85 Ensuring the proper nutrition is critical in female athletes, as energy deficiency long term can lead to the female athlete triad, which is characterized by low-energy availability, irregular or missed menstrual periods, and stress fractures and other bone problems due to changes in hormone levels, as well as other eating disorders.Citation82,Citation86 This can result in a lower production of estrogen, which is used to slow down bone resorption and stimulate bone formation – important factors in maintaining bone health.

Elite youth athletes may be at-risk for poor nutrition and eating disorders.Citation87 The German Young Olympic Athletes’ Lifestyle and Health Management Study collected data in 1,138 elite youth athletes with regard to eating disorders. Results showed that elite youth athletes who were most susceptible to eating disorders were athletes competing in weight-dependent sports, female athletes, and male athletes in endurance, technical, or power sports. Additionally, athletes who reported an eating disorder pathology were more likely to have depression and anxiety tendencies.Citation88 Similar studies have shown elite youth athletes are more likely to be energy deficient and at greater risk for disordered eating compared to nonathletes.Citation89,Citation90

Long-term consequences of injury

Sport injury not only reduces future participation in physical activity that adversely affects long-term health but may also lead to posttraumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA).Citation11,Citation91–Citation93 Osteoarthritis is characterized by joint pain and disability in the presence of radiographic changes such as cartilage loss, joint space narrowing, and osteophytes.Citation92 OA is the most common form of arthritis and is one of the most common chronic health conditions and a leading cause of pain and disability among adults.Citation94

Although OA generally affects older adults, evidence arising from several recent systematic reviews indicates that youth and younger adults may develop PTOA prematurely as a result of joint injury sustained in their youth.Citation92,Citation95 Specifically, Richmond et alCitation96 identified previous joint injury and history of meniscectomy as significant risk factors for knee OA (odds ratio [OR] =3.8; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.0, 7.2 and OR = 7.4; 95% CI: 4.0, 13.7, respectively). Similarly, Ajuied et alCitation95 reported that in individuals who suffered an ACL rupture, the relative risk of developing moderate-to-severe OA was 3.4 (95% CI: 1.84, 8.01) compared to an uninjured population.

These results are consistent with follow-up studies of young athletes who sustained meniscus or ACL injuries. In a study of 67 Swedish female soccer players with a confirmed ACL injury sustained before 20 years of age, radiographic evidence of OA was present in 51% of the injured knees after 12 years, compared with 8% in the uninjured knees.Citation96 Similarly, in 219 male soccer players, 14 years after ACL injury (age range at injury, 16–42 years), the prevalence of radiographic knee OA was 41% in the injured knees versus 4% in the uninjured knees.Citation97 In long-term follow-up of young athletes undergoing meniscus surgery, more than 50% developed knee OA with accompanying pain and physical decline.Citation98–Citation103 These epidemiologic studies are supported by evidence from animal models of ACL/meniscus injury and OA development.Citation104,Citation105

One recent study suggests that outcomes associated with early PTOA and other negative health consequences may be present as early as 3–10 years following knee injury in youth sport.Citation92 In preliminary analysis of the first year of their historical cohort study, Whittaker et alCitation92 reported evidence that youth/young adults report greater clinical symptomatology consistent with the onset and development of PTOA, and are at greater risk of being categorized as overweight/obese compared to matched uninjured controls.Citation92

As such, knee injury and related meniscus or ACL surgery suffered during elite youth sports may reduce future involvement in physical activity, leading to a less than optimal health in later life.Citation106 The knee, in particular, is the most common joint site for OA and, combined with the ankle, are the leading locations for injury in youth sports.Citation107 Notably, the most common injury location during the 2012 Youth Olympic Winter Games, the 2013 European Youth Sports Festival, and the 2014 Youth Olympics Games (US team) was the knee.Citation32–Citation34

Overtraining, burnout and injury

According to the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, a limited base of knowledge exists regarding burnout and overtraining injuries in elite youth athletes.Citation108 The difficult nature of quantifying overtraining and injury with regard to “hours played” or “hours practiced” does not allow for concrete guidelines of how much sport or exercise is too much.Citation109 Additionally, more and more pressure to succeed in sport has led to earlier sport specialization, and may increase rates of overuse injury and sport burnout. Sport burnout is a consequence of chronic stress that results in a young athlete stopping participation in a previously enjoyable sport. It is unknown what may cause burnout, but some theories suggest sport specialization, time conflicts or interest in other activities, or perhaps a psychological stressor. To aid in the prevention of burnout, diversified sports training may be more effective in developing elite-level skills that transfer over in the primary sport.Citation108

Furthermore, every sport has different risks for overtraining and overuse injuries. For example, individual sport athletes and females competing at the highest level have a 20%–30% higher incidence of injury.Citation110 Additionally, overtrained elite youth athletes are more likely to have frequent upper respiratory tract infections, muscle soreness, sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, mood disturbances, shortness of temper, decreased interest in training and competition, decreased self-confidence, and inability to concentrate.Citation110

Psychological risks for injury in elite athletes

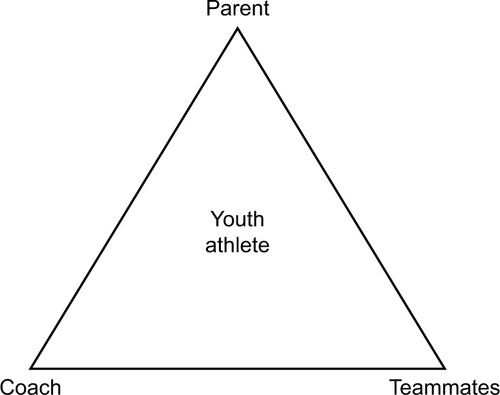

A discussion of injury affecting elite youth athletes would not be complete without consideration of psychological factors that may increase the risk of physical injury, and of the potential negative effects of elite level organized youth sport on the psychological well-being of its participants. A modified version of Hellstedt’s athletic triangle is used to identify risks of psychological injury that may be encountered by elite youth athletes.Citation9,Citation111 Hellstedt’s framework uses family systems theory to address the influence of the athlete, parents, and coaches on athletic development, and has implications for both physical and psychological performance and injury risk.Citation9,Citation111 As suggested in Kerr et al,Citation9 the impact of peers on athletic development and injury is significant. It is thus imperative that an investigation of psychological injury risks of elite youth athletes be examined from a multifaceted approach, as seen in .Citation9

Risk factors for injury

Life events

One of the most persistent findings in preinjury literature is research examining life-related stress.Citation112 Paralleling Williams and Anderson’sCitation112 model, literature has suggested that significant life event stress (defined as the perceived strain associated with stressors such as starting a new school, or the death of a family member), and more specifically negative event stress (the self-rated negative impact of those events), is highly predictive of injury occurrence in athletes.Citation113 Kerr and Minden’sCitation113 examination of stressful life events and injuries among young female gymnasts from the top two skill levels of the Canadian Gymnastic Federation, as well as Petrie’s reviewCitation114 among female collegiate gymnasts, indicate that negative life stress accounts for 11%–22% of injury variance. Holmes’Citation115 research among American football players further found 50% of those experiencing a high life stress reported injuries leading to at least three days of missed practice or one game, whereas one-quarter of those experiencing moderate life event stress reported injury. While receiving lesser focus, more common yet impactful life event stressors such as daily hassles or problems have similarly been found to accumulate over time, elevating the incidence of athletic injury.Citation116

Stress

Elite athletes are exposed to both physical and psychological stresses on a consistent basis, ranging from exercise- and competition-based stressors (eg, loss of a competition, exercise costs, and efforts) to common and daily stressors.Citation117 Research has increasingly examined the unique yet equally impairing contributions of competition-based and sport-unrelated stress. Worrying about athletic performance, the loss of a competition and resultant fear of failure and disaffection, conflicts with trainers, partners, or family, and costs associated with exercise and physical demands have all been implicated as having a significant impact on the stress levels of elite athletes such as youth and young adult figure skaters, golfers, and tennis players.Citation118–Citation121 Psychological stress has been shown to influence performance by narrowing an athlete’s attention and increasing his or her self-consciousness. In doing so, muscle tension is increased while simultaneously exposing coordination difficulties, thus enhancing injury risk.Citation122 Steffen et al’sCitation116 examination of female youth football players revealed that the risk of injury was 70% greater among those players with high perceived stress. The risk for such injuries is elevated among athletes self-reporting fewer social resources and/or coping skills to properly abate stress. Madison and Prapavessis’Citation123 research among rugby players found that negative stress accounted for 31% of the injury variance among those who used avoidance-focused coping behaviors (eg, denial), who reported having inadequate social support, and had a history of previous injuries. Rogers and LandersCitation124 similarly found that negative life stress and poor coping skills significantly contributed to injury occurring in young athletes. Simultaneously, high coping skills buffered the stress–injury relationship.

Athletic identity

The concept of athletic identity has similarly garnered increased focus in both sport and exercise psychology, and has significant implications for injury risk among elite youth athletes.Citation125,Citation126 Defined as “the degree to which an individual identifies with their athletic role”, athletic identity has been related to both positive and negative performance outcomes.Citation127 From a positive dimension, a healthy athletic identity has been linked to stronger commitment to training and a greater focus on athletic goals.Citation125,Citation128 Likewise, strong athletic identities are associated with positive psychological outcomes such as enhanced body image, increased self-confidence, and decreased anxiety, as a result of intensive training and successful performance.Citation128 Too little emphasis on alternative role identities, to the detriment of the athlete role, may however encourage the development of a unidimensional identity, often associated with negative impacts on an athlete’s well-being.Citation129 Elite athletes with strong and exclusively athletic identities risk the possibility of their self-worth and esteem becoming dependent on athletic performance.Citation130 Subsequently, if performance falls below perceived expectations, an athlete’s feelings of self-worth may be threatened.Citation131 It has similarly been suggested that unidimensional identities may lead to greater performance stress and expectations to succeed, which can result in prevalent athlete burnout, anxiety, and injury risk.Citation132

Depression

The relationship between stress, psychological disorders, and depression is well established, and has been similarly validated among elite athletes.Citation133 While it is established that physical activity positively impacts mental health, reviews have found that intense physical activity performed at the elite level might instead compromise mental well-being, increasing symptoms of anxiety and depression through overtraining, injury, and burnout.Citation134,Citation135 The peak competitive years for elite athletes tend to overlap with the peak age for the risk of onset of mental disorders, increasing the likelihood of depression-based injuries.Citation136 Research among collegiate athletes in the United States suggests the prevalence of depression ranges between 15.6% and 21%. Female athletes were found to experience greater depressive symptomatology, social anxiety, and nonsupport more frequently than male athletes, as well as male and female nonathletes.Citation137 Hammond et al’sCitation138 research among varsity swimmers at Canadian universities who were competing to represent Canada internationally found that 68% of athletes met criteria for a major depressive episode. The prevalence of depression doubled among the elite top 25% of athletes assessed, and performance failure was significantly associated with depression. Reported causes of depression among these elite athletes were varied, and included biological (eg, genetics), social (eg, conflicts), and psychological (eg, cognitive deficits) influences.Citation133

It is also worth noting that depression may not only precipitate the likelihood and severity of disease in athletes, but may also impact recovery and return to sport, as well as possibility of additional injury. Compared with a matched healthy group of collegiate athletes, Leddy et alCitation139 found that athletes who sustained a sport injury reported significantly greater depression symptoms at 1 week postinjury. At 2 months postinjury, athletes who were unable to participate reported greater depression symptoms of at least mild severity, and an estimated 12% of their sample exhibited depression symptoms of comparable severity to adults in outpatient treatment for depression. Manuel et alCitation140 similarly reported depression symptoms of at least moderate severity immediately postinjury as high as 27% among a sample of youth athletes. They reported approximately 21%, 17%, and 13% of athletes exhibited mild-to-moderate depression symptom severity at 3, 6, and 12 weeks postinjury, respectively. It is, therefore, plausible that depression may not merely enhance the risk of injury, but similarly return to play, and reinjury upon return due to cognitive, physiological, and neuromuscular deficits.

Sport specialization and overtraining may similarly generate depressive symptomatology among elite youth athletes. Intense single-sport training, at the exclusion of other sports, increases with age, significantly impacting elite young athletes. A study of the United States Tennis Association junior tennis players found that 70% began specializing at an average age of 10.4 years. Specialization rates gradually increased after the age of 14, with 95% of players specializing by 18 years.Citation141 The risks of intensive and specialized training include both adverse psychological stress and premature withdrawal from participation. Research supports the recommendation that child athletes avoid early sports specialization. Those who participate in a variety of sports and specialize only after reaching the age of puberty tend to be more consistent performers, have fewer injuries, and adhere to sports play longer than those who specialize early.Citation142 Swimmers who specialize earlier spend less time on a national team, and retire earlier than those who specialize later.Citation143 Minor league ice hockey players who retire from the sport began off-ice training earlier, and spent more time in off-ice training than those who continue to compete.Citation144 Butcher et al’sCitation145 retrospective review found that one in five youth athletes reported injury as the precipitating factor in their quitting or retiring from competition. Rhythmic gymnasts, those who specialized at earlier ages, and those spending more hours training from ages 4 to 16, rated their health lower and reported experiencing less fun.Citation146 Junior tennis players reporting early burnout likewise had less input into their training, higher perceived criticism and expectations from parents, and compromised levels of extrinsic motivation.Citation147

In addition to chronic muscle or joint pain, overtraining may similarly manifest itself in personality changes, decreased concentration and fatigue, and heightened levels of anxiety.Citation148,Citation149 Often overlooked, these symptoms place elite athletes at enhanced risk for injury. O’Conner et al,Citation150 for example, found significant correlations between exercise loads and depressive mood states in collegiate-level swimmers. Nixdorf et alCitation151 similarly noted a strong association between the balance of stress and recovery and depressive symptoms among elite German athletes. Athletes with heightened levels of exhaustion and lower levels of recovery experienced significantly greater depressive symptoms. Research on overtraining in sports has further demonstrated the influence of physiological adjustments, such as leptin and insulin levels, on psychological markers such as mood, feelings, or fatigue – each of which enhances injury risk.Citation152 Yet despite enhanced risk, elite young athletes seek professional counseling or support less often, out of fear of appearing weak, losing training time, or losing respect of their coaches and peers.Citation152

Competition anxiety

Ample literature similarly implicates maladaptive fatigue and an inability to control stress as impacting competitive anxiety, thus influencing injury risk. Maladaptive fatigue syndrome occurs when athletes are incapable of addressing stress, resulting in chronic anger, hostility, confusion, depression, apathy, or anxiety. Fatigue-based anxiety impacts balance among gymnasts, negatively impacting short- and long-term performance.Citation153,Citation154 Kolt and Kirkby’s Citation155 research involving young elite gymnasts similarly suggested that heightened cognitive anxiety impacts not only the risk, but also severity, of injury.Citation155

Maladaptive perfectionist tendencies

Broadly considered a personality characteristic reflecting a compulsive pursuit of exceedingly high standards, coupled with a tendency to engage in overly critical appraisal, perfectionism is a construct whose core elements not only regulate different forms of achievement striving, but also give rise to psychological processes that may lead to maladaptive outcomes.Citation156–Citation158 Substantial impacts of perfectionist tendencies on anxiety, stress, depression, and fatigue have been documented. Although many sports require perfection, unhealthy patterns of behavior as well as negative and self-defeating outcomes are evident among athletes characterized by an extreme perfectionist personality.Citation159 Research among varsity-level athletes found associations between concerns over mistakes and outcomes such as increased anxiety, thus influencing both risk and severity of injury.Citation160

Potential for psychological injury

Parental influences

The parental impact on elite youth athlete development, success, and injury risk may be both valuable and detrimental. Parents often play a critical role in athletic development, introducing their children to sport while providing both financial and psychological support through the training and competition phases. Despite such benefits, our extensive review of the literature suggests that parental and caretaker behaviors may adversely impact elite young athletes’ psychological health.

Elite young athletes’ perceptions of parental overinvolvement have been positively correlated with both anxiety and burnout. Dunn et alCitation161 found that perceived parental pressure was directly related to negative stress among athletes and that levels of motivation were negatively associated with increased levels of parental pressure. Similarly, Gould et alCitation162 found that junior-level tennis players who felt that they had high levels of pressure from family members may feel high levels of worry and anxiety. Parental pressure has also been found to impact the athlete’s perception of self, thus impacting injury risk.Citation162

Exaggerated performance expectations often elicit severe criticism from parents. While not focusing specifically on elite-level youth, Shields et al’sCitation163 examination of parents of fifth- through eighth-grade athletes revealed that 13% had angrily criticized their child’s sport performance. Such findings mirror those of Kidman et alCitation164 and Blom and Drane,Citation165 both of whom reported that nearly one-third of verbal comments from parents of youth athletes were negative, ranging from corrective to scolding behaviors.

Another important mechanism of parental influence is modeling of dysfunctional eating attitudes and behaviors. Several studies among adolescent girls and their parents have shown significant associations between abnormal eating attitudes of mothers and daughters.Citation166,Citation167 Blackmer et alCitation168 found greater body image disturbances and higher levels of disturbed eating attitudes among both female and male college athletes who reported family climates with low perceived support and autonomy. In a previous study examining individual and relational risk factors (eg, self-esteem, social pressure for thinness), Francisco et alCitation169 found direct parental influences (eg, weight teasing) on disordered eating among elite athletes, yet not on that of nonelite athletes or participants in the control group.

In addition to directly influencing the psychological health of elite athletes, parents play a vital role in navigating their child’s relationships with others. Often socialized into the sport culture, and left to accept the authority and expertise of coaches, parents may indirectly contribute to emotionally abusive coaching practices by normalizing such behaviors as routine.Citation170,Citation171

Coaching influences

The influence of coaching strategies and/or practices on psychological harm among elite youth athletes should similarly not be overlooked. Often researched from the scope of adolescent development, psychology, sociology, and social work, a focus on emotional abuse in sport is at a formative level. Defined as “patterns of nonphysical harmful interactions” between a child and caregiver, studies of emotionally abusive coaching are limited to athletes and student-athletes 18 years of age and older.Citation9,Citation172 Alexander et al’sCitation173 research among 18- to 22-year-old athletes in the United Kingdom found the risk of experiencing emotional harm was more than three times that of physical harm. More than one-third (34%) of athletes indicated being treated in an emotionally harmful manner by either a coach or trainer, with little sex-based variability. Emotionally abusive practices were more commonly reported among athletes from individual sports (eg, swimming and dance) than those participating in team sports (eg, football, hockey, rugby), and included yelling, belittlement, making degrading comments, and throwing objects with the purpose of intimidating the athlete.Citation173

The continued growth of social media has continued to raise public awareness of coaching-related practices that are psychologically damaging to elite young athletes. For example, accounts of Olympic gold medalist Dominique Moceanu’s long-term struggles with psychological harm resulting from coaching and parental degradation have increased awareness of and advocacy for monitoring of training, practice, and competitive activities.Citation174 Acts of omission, such as neglect, or failure to take action to prevent injury, which often occurs when coaches minimize the impact of bullying or hazing, similarly impact levels of athlete anxiety and depression, and have been widespread in the media.Citation175

Strategies to ensure physical and emotional health

There are presently no studies designed to determine the effectiveness of injury prevention measures in elite youth sports specifically. However, there is adequate evidence arising from injury prevention studies of youth sport participants to inform practice and policy recommendations to prevent injuries in elite youth sport settings.Citation91,Citation176–Citation178 The focus of this research has been primarily on neuromuscular training programs, protective equipment and sporting rules, and eating disorders intervention.

Physical/physiological prevention strategies

Multifaceted neuromuscular training programs

The most common injuries in youth sport involve the lower extremity, accounting for over 60% of the overall injury burden in youth sport.Citation62,Citation179 On the basis of relative burden, the focus of much of the evidence surrounding injury prevention in youth sport has been on reducing the risk of lower extremity injuries.Citation116 These neuromuscular training strategies primarily target intrinsic risk factors such as previous injury, decreased strength, endurance, flexibility, and postural control.Citation91

The results of a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reveal a substantial overall protective effect of neuromuscular training in reducing the risk of lower extremity injury in youth team sport (incidence rate ratio =0.64; 95% CI: 0.40–0.84) or a 36% reduction in lower extremity injury risk.Citation118 In this study, the combined estimate for RCT studies examining the preventative effect of neuromuscular training in the reduction of knee injuries in youth team sport (soccer, European handball, basketball) suggests a protective effect of knee injuries specifically, but this finding was not statistically significant (incidence rate ratio =0.74 [95% CI: 0.51–1.07]).

Protective equipment

Using protective equipment may help to prevent injury in many sports. Although preventative studies have not often been conducted involving athletes in elite youth sports, the results of studies with youth and adult athletes are pertinent. Three systematic reviews involving a combination of youth and adult populations support the effectiveness of helmets in skiing and snowboarding in reducing the risk of head injuries.Citation180–Citation182 In studies that included children, the associated OR was 0.41 (95% CI: 0.27–0.59).Citation180

Although no RCTs have evaluated face shields, several cohort studies have shown a protective effect of face shields on risk of injuries, including facial lacerations, facial fractures, dental injuries, and head injuries.Citation183–Citation185 Stuart et alCitation185 documented a dose–response effect with the amount of facial protection provided among ice hockey players; risk of injury decreased by 54% with the use of partial face shields, and injury risk decreased by 85% with the use of full face shields. Benson et alCitation183 also showed that the use of the full face shield significantly reduced the amount of playing time lost because of concussion, suggesting that concussion severity may be reduced by the use of a full face shield.

A systematic review examining wrist guards in snowboarding reveals a significant protective effect in reducing the risk of wrist injury (OR =2.3), wrist fracture (relative risk [RR] =0.29), and wrist sprains (RR =0.17).Citation186

There is sufficient evidence arising from youth populations to endorse the use of protective equipment in elite youth sport, yet despite this evidence there is also evidence to support the less than optimal uptake of equipment strategies.Citation91

Sporting rules

All sports have specific rules for the purpose of regulating the game or sporting activity. Some sporting rules have been developed for the specific purpose of decreasing the risk of injury in youth sports – for example, rules against “spearing” in gridiron football and rules mandating the use of face shields in ice hockey. Although these changes helped to reduce youth sports injuries, including catastrophic injuries such as blindness in hockey and paralysis in football, relatively few studies have systematically evaluated the effect of rules or rule changes on the risk of sports injuries. An exception is the evaluation of body checking in youth ice hockey. In a recent meta-analysis, policy allowing body checking in youth age groups was a significant injury risk factor (RR =2.45; 95% CI: 1.7–3.6).Citation187 In a cohort study comparison of leagues with and without body checking in 11- and 12-year-old players showed a three- to fourfold increased risk of injury where body checking was allowed. These findings led to a national policy change in Canada and the United States.Citation91

Social-cognitive eating disorders intervention

To combat the effects of eating disorders in elite young athletes, Martinsen et alCitation188 conducted an RCT to prevent the development of new cases of eating disorders among elite Norwegian high-school athletes representing a variety of sports/disciplines. Their social-cognitive intervention was successful at preventing new cases of eating disorders and symptoms associated with eating disorders in adolescent elite female athletes. Similarly, a 1-year RCT targeted increased knowledge and strategies for healthy nutrition, eating behavior, and eating disorders. Results showed that coaches and athletes successfully increased knowledge for weight recognition and management, and coaches had more knowledge of eating disorders at the end of the intervention compared to controls.Citation189 Thus, interventions that target eating disorders and knowledge of eating disorders have been shown to be successful. These interventions are necessary to achieve adequate nutrition and prevent eating disorders in elite youth athletes, especially to prevent injury.

Psychosocial prevention strategies

If not managed correctly, stress, anxiety, depression, and burnout can have substantial impacts on an athlete’s welfare, affecting both mental and physical readiness to perform.Citation190 It is thus imperative that both physiological and psychological athletic wellness are consistently monitored. In the absence of intervention research, there are a number of ways in which the psychological wellness of elite junior athletes can be monitored and/or managed, thus limiting the risk of injury.

Coping mechanisms

Coping with stress in sport is an essential self-regulatory factor that promotes optimal levels of achievement.Citation191 Individually focused factors such as personality, motivation, and cognitive evaluation are key predictors of sport-related coping. Task-oriented coping engages strategies to directly manage a stressful circumstance (eg, problem-focused) and its resulting cognitive and affective activation. Also referred to as approach or engagement coping, task orientation includes strategies such as effort expenditure, thought control, relaxation, logical analysis, mental imagery, and support seeking. Indicators of task-oriented coping have been associated with both objective and subjective achievement indicators, and thus decreased risk of injury among athletes.Citation191

Burnout and optimism

Elite young athletes are at risk of developing burnout, as they face not only high physical demands but also psychological pressure to reach an elite level. Burnout appears to be linked to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors in one’s relationship with his/her work.Citation192 Related to stress associated with intense training and competition demands, exhaustion is a central contributor to burnout. Reduced sense of athletic accomplishment is manifested in a perception of low ability with regard to performance and skill level. Manifesting itself in a loss of motivation, such sport devaluation, may lead to enhanced risk of injury.Citation108 By fostering protective factors such as optimism, elite young athletes may, therefore, reduce stress and burnout, thus minimizing injury risk.

Regarded as a generalized outcome expectancy or sense of confidence that a goal can be attained, optimism is associated with a sense of control and confidence, making optimists more likely to adopt active and proactive coping strategies, while less likely to engage in avoidance coping. Thus, negative consequences such as poor health, poor performance, and injury risk are abated. Studies among elite-level male and female wrestlers have shown a significantly inverse relationship between optimism and both stress and burnout, with optimistic athletes displaying lower levels of emotional/physical exhaustion and sport devaluation, and less of a reduced sense of accomplishment.Citation123,Citation192 It thus appears that optimism is associated with lower perceptions of burnout and consequently injury risk.Citation108

Hardiness and mental toughness

Hardiness represents a trait-like characteristic that influences the manner in which individuals perceive and react to stressful circumstances. Research among adult athletes has shown that hardy individuals are more effective in coping with stress, thus offering protection against stress-induced health issues.Citation191 Hardiness similarly reflects a state of mental toughness, in that it encapsulates control, commitment, and challenge. Utilized in an athletic setting, such concepts allow athletes to make appropriate decisions about how to cope with stressful situations. Mentally tough individuals are characterized by a strong tendency to view their personal environment as controllable, to perceive themselves as capable and influential, to stay committed even under adverse circumstances, and to consider problems as natural challenges.Citation193 From an athletic performance standpoint, research indicates that elite youth cricketers (Mage =16.45 years) with elevated mental toughness possessed more developmental assets such as support, empowerment, and a positive identity, and lower levels of negative emotional states – each of which has been associated with optimal performance.Citation194

Parent and coaching roles

Parents and coaches play an important role in helping elite young athletes learn about coping by creating a support context for learning, and by using a number of specific strategies to help athletes learn about coping, including questioning and reminding athletes about effective coping strategies, providing perspective, sharing their own experiences, dosing or structuring potentially stressful experiences for athletes, initiating formal conversations about coping, creating learning opportunities, and direct instruction about coping.Citation195

Research has found specific preferences among elite young athletes for parental involvement, which may impact performance and risk of injury. Those preferences include making comments on effort and attitude, rather than performance, as well as providing practical advice that balanced supportive comments and nonverbal behaviors.Citation196 Similarly, athletes preferred specific behaviors before, during, and after competition. Prior to competition, athletes wanted parents to help them prepare physically and mentally, including ensuring proper hydration while helping the athlete to relax. During competition, athletes wanted parents to encourage the entire team, focusing on the athletes’ efforts rather than on the outcome of the competition. Athletes similarly did not want parents to coach from the sidelines, argue with officials, or engage in behaviors that would draw attention to themselves or the athletes.Citation195,Citation197 Autonomous support from parents, such as showing an interest, listening wherever possible, supporting the athlete’s desires, and allowing him/her to participate in decisions, has similarly been shown to have positive influences on motivation and performance, thus minimizing injury risk.Citation198

In deference to a controlling style where autocratic decisions are made, and control is asserted through threats, autonomous support from coaches has similarly been found to positively influence motivation and performance. In addition to providing autonomous support, providing encouragement after mistakes, as well as expertise in training and practice, plays a role in motivating an athlete to achieve while minimizing injury risk.Citation198 This observation is critically important, since the specializing career stage of elite young athletes is partially characterized by a shift toward specialist coaching.Citation199

Organizational culture

An effective, proactive, and preventive organizational approach to enhancing emotional health and reducing psychological risks for injury seeks to make changes in both the macro- and microenvironment, by impacting both organizational culture and task design and activity. A proactive approach that addresses the underlying causes of psychological distress, establishes effective coping mechanisms to recognize and respond to stressors, and properly identifies the perspectives of elite young athletes, has shown to moderate external pressures and reduce injury risk.Citation200 An organizational culture with a proper focus on monitoring and modification of training demands would similarly abate psychological strain, and its impending contribution to athletic injury.

Conclusion

Elite youth athletes have competed in international sporting events for more than 50 years. However, international sporting events such as the YOG, designed exclusively for elite youth athletes, are a relatively new phenomenon. Engaging in elite youth sport not only has important health benefits but also involves risk of injury, given the intensive training programs and high frequency of elite youth participation. Although there is lack of epidemiological data, preliminary data suggest that the risk of physical and psychological injury is high.

Although there is a paucity of research on risk factors specifically related to injury affecting elite youth athletes, research involving other young athletes may be generalizable to elite youth athletes. In this regard, modifiable risk factors such as balance deficiency, competition anxiety, life events, previous injury, volume of training, and fatigue may have particular application for elite youth athletes, given the rigor and volume of their training and competitive regiments.

There are presently no studies designed to determine the effectiveness of injury prevention measures in elite sports specifically. However, there is adequate evidence arising from injury prevention studies of youth sports participants – including neuromuscular training, protective equipment, mental training to enhance self-esteem, and sport rules modification – to prevent injuries in elite youth sports settings. Although not tested, psychosocial prevention strategies such as adoption of task-oriented coping mechanisms, autonomous support from parents, and a proactive organizational approach also show promise in injury prevention.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CaineDJAre kids having a rough time of it in sports?Br J Sports Med2010441320026697

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeleletal and Skin DiseasesPreventing musculoskeletal sports injuries in youth: a guide for parents62013 Available at http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Sports_Injuries/child_sports_injuries.aspAccessed May 25, 2014

- MountjoyMArmstrongNBizziniLIOC consensus statement: training the elite child athleteBr J Sports Med200842316316418048429

- SteffenKEngebretsenLMore data needed on injury risk among elite young athletesBr J Sports Med20104448548920460261

- EngebretsenLSteffenKBahrRThe International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement on age determination in high level young athletesBr J Sports Med201044747648420519254

- Olympic.orgOfficial website of the Olympic Movement. What is the Youth Olympic Games? Available at: https://www.olympic.org/youth-olympic-gamesAccessed March 30, 2016

- HeggieTWCaineDJEpidemiology of Injury in Adventure and Extreme SportsBasel, SwitzerlandKarger2012116

- ArmstrongNMcManusAMPreface. The elite young athleteMed Sport Sci2011561321178364

- KerrGStirlingAMacPhersonEPsychological injury in pediatric and adolescent sportsCaineDPurcellLInjury in Pediatric and Adolescent Sports: Epidemiology, Treatment and PreventionNew York, NYSpringer2016179190

- FieldsSKCollinsCLComstockRDViolence in youth sports: hazing, brawling and foul playBr J Sports Med201044323719858113

- CaineDJGolightlyYMOsteoarthritis as an outcome of paediatric sport: an epidemiological perspectiveBr J Sports Med201145529830321330645

- WildCYSteeleJRMunroBJMusculoskeletal and estrogen changes during the adolescent growth spurt in girlsMed Sci Sports Exerc20134513814522843105

- MicheliLJOveruse injuries in children’s sports: the growth factorOrthop Clin North Am1983143373606843972

- MaffulliNCaineDThe younger athleteBruknerPKhanKClinical Sports Medicine4th edSydney, AustraliaMcGraw-Hill2012888909

- MalinaRMBouchardCBar-OrOGrowth, Maturation, and Physical Activity2nd edChampaign, ILHuman Kinetics2004267273

- PurcellLConcussion in youth athletesCaineDPurcellLInjury in Pediatric and Adolescents Sports: Epidemiology, Treatment and PreventionNew York, NYSpringer2016151162

- McCroryPMeewisseWHAubryMConsensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012Br J Sports Med20134725025823479479

- HarmonKGDreznerJGammonsMAmerican Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sportClin J Sport Med201343783802

- CaineDCaineCChild camel jockeys: a present-day tragedy involving children and sportClin J Sport Med200515528728916162984

- National Center for Injury Prevention and ControlCDC Injury Research Agenda 2009–2018Atlanta, GACenters for Disease Prevention and Control Available from: http://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21769Accessed January 1, 2009

- GriffinLYAlbohmMJArendtEAUnderstanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a review of the Hunt Valley II meeting, January 2005Am J Sports Med2006341512153216905673

- Hastmann-WalshTCaineDJInjury risk and its long-term effects for youthBakerJSafaiPFraser-ThomasJHealth and Elite Sports: Is High Performance Sport a Healthy Pursuit?New York, NYRoutledge20156580

- JohnsonADohertyDJFreemontAInvestigation of growth, development, and factors associated with injury in elite schoolboy footballers: prospective studyBMJ2009338b49019246550

- LeGallFCarlingCReillyTInjuries in young elite female soccer players: an 8-season prospective studyAm J Sports Med20083627628417932408

- LeGallFCarlingCReillyTVandewalleHChurchJRochcongarPIncidence of injuries in French youth soccer players: a 10 season studyAm J Sports Med20063492899816436535

- YungPSHEpidemiology of injuries in Hong Kong elite badminton athletesRes Sports Med20071513314617578753

- HägglundMWaldénMEkstrandJUEFA injury study-an injury audit of European championships 2006 to 2008Br J Sports Med20094348348919246461

- WaldénMHägglundMEkstrandJFootball injuries during European Championships 2004–2005Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc2007151155116217375283

- JungeADvorakJInjuries in female football players in top-level international tournamentsBr J Sports Med200741Suppl 1i3i717646248

- JungeADvorakJGraf-BaumannTPetersonLFootball injuries during FIFA tournaments and the Olympic Games 1998–2000: development and implementation of an injury reporting systemAm J Sports Med2004321 Suppl805895

- CaineDJNassarLGymnastics injuriesCaineDJMaffuliNEpidemiology of Pediatric Sports Injuries: Individual SportsBasel, SwitzerlandKarger20051858

- NabhanDWaldenTStreetJLindenHMoreauBSports injury and illness epidemiology during the 2014 Youth Olympic Games: United States Olympic team surveillanceBr J Sports Med2016501168869327098886

- RuedlGSchobersbergerWPoceccoESport injuries and illnesses during the first Winter Youth Olympic Games 2012 in Innsbruck, AustriaBr J Sports Med2012461030103723148325

- van BeijsterveldAMCThizsKMBackxFJGSteffenKBrozičevićVStubbeJHSports injuries and illnesses during the European Youth Olympic Festival 2013Br J Sports Med20154944845225573616

- RuedlGSchnitzerMKirschnerWSports injuries and illnesses during the 2015 Winter European Youth Olympic FestivalBr J Sports Med20165063163626884224

- KnowlesSBMarshallSWBowlingMJRisk factors for injury among high school football playersEpidemiol2009202302310

- MalinaRMMoranoPJBarronMIncidence and player risk factors for injury in youth footballClin J Sport Med20061621422216778541

- EmeryCAMeeuwisseWHInjury rates, risk factors, and mechanisms of injury in minor hockeyAm J Sports Med2006341960196916861577

- McKayCCampbellTMeeuwisseWEmeryCThe role of psychological risk factors for injury in elite youth ice hockeyClin J Sports Med2013233216221

- EmeryCAMeeuwisseWHHartmannSEEvaluation of risk factors for injury in adolescent soccer. Implementation and validation of an injury surveillance systemAm J Sports Med2005331882189116157843

- CaineDKnutzenKHoweWA three-year epidemiological study of injuries affecting young female gymnastsPhys Ther Sport200341023

- BaileyDAWedgeJHMcCullochRGMartinADBernhardsonSCEpidemiology of fractures of the distal end of the radius in children as associated with growthJ Bone Joint Surg Am198971122512312777851

- DugglebyTKumarSEpidemiology of juvenile low back pain: a reviewDisabil Rehabil1997195055129442988

- DiFioriJPPufferJCAishBDoreyFWrist pain in young gymnasts: frequency and effects on training over 1 yearClin J Sport Med20021234835312466689

- NiemeyerPWeinbergASchmittHStress fracture in the juvenile skeletal systemInt J Sport Med200627242249

- PliskyPJRauhMJKaminskiTWUnderwoodFBStart excursion balance test as a predictor of lower extremity injury in high school basketball playersJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther20063691191917193868

- WangHKChenCHShiangTYJanMHLinKHRisk-factor analysis of highs school basketball player ankle injuries: a prospective controlled cohort study evaluating postural sway, ankle strength, and flexibilityArch Phys Med Rehabil200687682182516731218

- TrojiianTHMcKeagDBSingle leg balance test to identify risk of ankle sprainsBr J Sports Med20064061061316687483

- McGuineTAGreeneJJBestTLeversonGBalance as a predictor of ankle injuries in high school basketball playersClin J Sport Med20001023924411086748

- BackousDDFriedlKESmithNJParrTJCarpineWDJrSoccer injuries and their relation to physical maturityAm J Dis Child19881428398423394676

- LinderMMTownsendDJJonesJCBalkcomILAnthonyCRIncidence of adolescent injuries in junior high school football and its relationship to sexual maturityClin J Sport Med199551671707670972

- LeGallFCarlingCReillyTBiological maturity and injury in elite youth footballScand J Med Sci Sports200717556457217076832

- StuartMJMorreyMASmithAMInjuries in youth football: a prospective observation cohort analysis among players aged 9–13 yearsMayo Clin Proc200277431732211936925

- GomezJDRossSKCalmbachWKimmelRBSchmidtDRDhandaRBody fatness and increased injury rates in high school football linemanClin J Sport Med199881151209641441

- KaplanTADigelSLScavoVAArellanaSBEffect of obesity on injury risk in high school football playersClin J Sport Med1995543477614081

- KnowlesSBMarshallSWGuskiewiczKMIssues in estimating risks and rates in sports injury researchJ Athl Train20064120721516791309

- HuffmanEAYardEEFieldsSKCollinsCLComstockRDEpidemiology of rare injuries and conditions among United States High School Athletes during 2005–2006 and 2006–2007J Athl Train200843662463019030141

- RechelJACollinsCLComstockRDEpidemiology of injuries requiring surgery among high school athletes in the United States, 2005 to 2010J Trauma201171498298921986739

- MararMMcIlvainNMFieldsSKComstockRDEpidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sportsAm J Sports Med201240474775522287642

- TenfordeASSayresLCMcCurdyMLSainaniKLFredericsonMIdentifying sex-specific risk factors for stress fractures in adolescent runnersMed Sci Sports Exerc201345101843185123584402

- RauhMJKoepsellTDRivaraFPMargheritaAJRiceSGEpidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries among high school cross-country runnersAm J Epidem20061632151159

- CaineDCaineCMaffulliNIncidence and distribution of pediatric sport-related injuriesClin J Sport Med200616650051317119363

- EmeryCAHagelBDecloeMCarlyMRisk factors for injury and severe injury in youth ice hockey: a systematic review of the literatureInj Prev201016211311820363818

- CusimanoMDTabackNAMcFaullSRHodginsRBekeleTMElfekiNCanadian Research Team in Traumatic Brain Injury and ViolenceEffect of body checking on rate of injuries among minor hockey playersOpen Med201151e57e6422046222

- EmeryCAKangJShrierIRisk of injury associated with body checking among youth ice hockey playersJAMA2010303222265227220530780

- DunSLofticeJFleisigGSKingsleyDAndrewsJRA biomechanical comparison of youth baseball pitches: is the curveball potentially harmful?Am J Sports Med20053668669218055920

- FleisigGSAndrewsJRCutterGRRisk of serious injury for young baseball pitchers: a 10-year prospective studyAm J Sports Med201139225325721098816

- DennisRJFinchCFFarhartJPIs bowling workload a risk factor for injury to Australian junior cricket fast bowlers?Br J Sports Med2005391184384616244195

- HjelmNWernerSRenstromPInjury risk factors in junior tennis players: a prospective 2-year studyScand J Med Sci Sports2012221404820561286

- DiFioriJPMandelbaumBRWrist pain in a young gymnast: unusual radiographic findings and MRI evidence of growth plate injuryMed Sci Sports Exerc19962812145314588970137

- LoudKJGordonCMMicheliLJFieldAECorrelates of stress fractures among preadolescent and adolescent girlsPediatrics20051154e399e40615805341

- LukeALazaroRMBergeronMFSports-related injuries in youth athletes: is overscheduling a risk factor?Clin J Sport Med201121430731421694586

- OlsenSJFleisigGSDunSLofticeJAndrewsJRRisk factors for shoulder and elbow injuries in adolescent baseball pitchersAm J Sports Med200634690591216452269

- LymanSFleisigGSWaterborJWLongitudinal study of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchersMed Sci Sports Exerc200133111803181011689728

- PintoMKuhnJEGreenfieldMLHawkinsRJProspective analysis of ice hockey injuries at the junior A level over the course of one seasonClin J Sport Med199992707410442620

- Thein-NissenbaumJMRauhMJCarrKELoudKJMcGuineTAAssociations between disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction, and musculoskeletal injury among high school athletesJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther2011412606921212503

- RauhMJNicholsJFBarrackMTRelationships among injury and disordered eating, menstrual dysfunction, and low bone mineral density in high school athletes: a prospective studyJ Athl Train201045324325220446837

- CaineDGoodwinBInjury risk factors in pediatric and adolescent sportsCaineDPurcellLInjury in Pediatric and Adolescent Sports: Epidemiology, Treatment and PreventionNew York, NYSpringer2016191204

- HarmerPInjury research in pediatric and adolescent sportsCaineDPurcellLInjury in Pediatric and Adolescent Sports: Epidemiology, Treatment and PreventionNew York, NYSpringer2016233242

- FurnhamABadminNSneadeIBody image dissatisfaction: gender differences in eating attitudes, self-esteem and reasons for exerciseJ Psychol2002136658159612523447

- National Association of Anorexia Nevrosa and Associated Disorders2013 Available at: http://www.anad.org/get-information/about-eating-disorders/eating-disorders-statistics/Accessed April 25, 2016

- ShriverLHBettsNMWollenbergGDietary intakes and eating habits of college athletes: are female collegiate athletes following the current sports nutritional standards?J Am Coll Health2013611101623305540

- NutterJSeasonal changes in female athletes dietsInt J Sport Nutr1991143954071844571

- SchillingLNikitaMWhat coaches need to know about the nutrition of female high school athletes: a dietitian’s perspectiveStrength Condit J20083051617

- BuchholzAMackHMcVeyGFederSBarrowmanNBodySense: an evaluation of a positive body image intervention on sport climate for female athletesEat Disord20081630832118568921

- AboodDABlackDRBirnbaumRDNutrition education intervention for college female athletesJ Nutr Educ Behav200436313513715202989

- PratherHHuntDMcKeonKAre elite female soccer athletes at risk for disordered eating attitudes, menstrual dysfunction, and stress fractures?PM R20168320821326188245

- GielKEHermann-WernerAMayerJEating disorder pathology in elite adolescent athletesInt J Eat Disorder2016496553562

- MartinsenMSundgot-BordenJHigher prevalence of eating disorders among adolescent elite athletes than controlsMed Sci Sports Exerc20134561188119723274604

- MuiaENWrightHHOnywereVOKuriaENAdolescent elite Kenyan runners are at risk for energy deficiency, menstrual dysfunction and disordered eatingJ Sports Sci201634759860626153433

- EmeryCRoyTOHagelBMacphersonANettel-AquirreAInjury prevention in youth sportCaineDPurcellLInjury in Pediatric and Adolescent Sports: Epidemiology, Treatment and PreventionNew York, NYSpringer2016205229

- WhittakerJLWoodhouseLJNettel-AguirreAEmeryCAOutcomes associated with early post-traumatic osteoarthritis and other negative health consequences 3–10 years following knee joint injury in youth sportOsteoarthritis Cartilage20152371122112925725392

- GolightlyYMMarshallSWCaineDJFuture shock: youth sports and osteoarthritis riskLower Extremity Rev20113102227

- AllenKDGolightlyYMEpidemiology of osteoarthritis: state of the evidenceCurr Opin Rheumatol201527327628325775186

- AjuiedAWongFSmithCAnterior ligament injury and radiologic progression of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Sports Med20144292242225224214929

- RichmondSAFukuchiRKEzzatASchneiderKSchneiderGEmeryCAAre joint injury, sport activity, physical activity, obesity, or occupational activities predictors for osteoarthritis? A systematic reviewJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther201343851551923756344

- von PoratARoosEMRoosHHigh prevalence of osteoarthritis 14 years after an anterior cruciate ligament tear in male soccer players: a study of radiographic and patient relevant outcomesAnn Rheum Dis2004633260273

- McNicholasMJRowleyDIMcGurtyDTotal meniscectomy in adolescence: a thirty-year follow-upJ Bone Joint Surg Br200082221722110755429

- DaiLZhangWXuYMeniscal injury in children: long-term results after meniscectomyKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc19975277799228312

- WrobleRRHendersonRCCampionERMeniscectomy in children and adolescents: a long-term follow-up studyClin Orthop Relat Res19922791801891600654

- ManzioneMPizzutilloPDPeoplesABSchweizerPAMeniscectomy in children: a long-term follow-up studyAm J Sports Med19831131111156688155

- ZamanMLeonardMAMeniscectomy in children: results in 59 kneesInjury19811254254286894909

- MedlarRCMandibergJJLyneEDMeniscectomies in children. Report of long-term results (mean, 8.3 years) of 26 childrenAm J Sports Med19808287926892670

- AndersonDDChubinskayaSGuilakFPost-traumatic osteoarthritis: improved understanding and opportunities for early interventionJ Orthop Res201129680280921520254

- FlemingBCHulstynMJOsksendahlHLFadalePDLigament injury, reconstruction, and osteoarthritisCurr Opin Rheumatol2005165354362

- MaffulliNLongoUGGougouliasNLoppiniMDenaroVLong-term health outcomes of youth sports injuriesBr J Sports Med2010441212519952376

- CaineDJDalyRMJollyDHagelBECochraneBRisk factors for injury in young competitive female gymnastsBr J Sports Med2006408994

- DiFioriJPBenjaminHJBrennerJOveruse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports MedicineClin J Sport Med201424132024366013

- RobertsWOOveruse injuries and burnout in youth sportsClin J Sport Med20142411224366012

- WinsleyRMatosNOvertraining and elite youth athletesMed Sport Sci2011569710521178369

- HellstedtJCThe coach/parent/athlete relationshipSport Psychol19871151160

- WilliamsJMAndersenMBPsychosocial antecedents of sport injury: review and critique of the stress and injury modelJ Appl Sport Psychol1998101525

- KerrGMindenHPsychological factors related to the occurrence of athletic injuriesJ Sport Exerc Psychol198810167173

- PetrieTAPsychosocial antecedents of athletic injury: the effects of life stress and social support on female college gymnastsBehav Med19921831271381421746

- HolmesTHPsychological screeningFootball Injuries. Papers presented at a workshop Sponsored by Subcommittee on Athletic Injuries, Committee on the Skeletal System, Division of Medical Sciences, National Research Council21969Washington, DCNational Academy of Sciences211214

- SteffenKPensgaardABahrRSelf-reported psychological characteristics as risk factors for injuries in female youth footballScand J Med Sci Sports200919344245118435692

- PufferJCMcShaneJMDepression and chronic fatigue in athletesClin Sports Med19921123273381591789

- CohnPJAn exploratory study on sources of stress and athlete burnout in youth golfSport Psychol19904295106

- GouldDJacksonSFinchLSources of stress in national champion figure skatersJ Sport Exerc Psychol1993152134159

- Puente-DiazRAnshelMHSources of acute stress, cognitive appraisal, and coping strategies among highly skilled Mexican and U.S. competitive tennis playersJ Soc Psychol2005145442944616050340

- ScanlanTKSteinGLRavizzaKAn in-depth study of former elite figure skaters: sources of stressJ Sport Exerc Psychol1991132103120

- American College of Sports MedicineAmerican Academy of Family PhysiciansAmerican Academy of Orthopaedic SurgeonsAmerican Medical Society for Sports MedicineAmerican Orthopaedic Society for Sports MedicineAmerican Osteopathic Academy of Sports MedicinePsychological issues related to injury in athletes and the team physician: a consensus statementMed Sci Sports Exerc200638112030204017095938

- MadisonRPrapavessisHA psychological approach to the prediction and prevention of athletic injuryJ Sport Exerc Psychol200527289310

- RogersTJLandersDMMediating effects of peripheral vision in the life event stress/athletic injury relationshipJ Sport Exerc Psychol200527271288

- AndersonCBMasseLCZhangHColemanKJChangSContribution of athletic identity to child and adolescent physical activityAm J Prev Med200937322022619595559

- VisekAJHurstJRMaxwellJPWatsonJCA cross-cultural psychometric evaluation of the athletic identity measurement scaleJ Appl Sport Psychol200820473480

- BrewerBWVan RaalteJLLinderDEAthletic identity: Hercules’ muscles or Achilles heel?Int J Sport Psychol1993242237254

- HortonRSMackDEAthletic identity in marathon runners: functional focus or dysfunctional commitment?J Sport Behav2000232101119

- MillerPSKerrGAThe athletic, academic and social experience of intercollegiate student athletesJ Sport Behav2002254346367

- RybaTVAunolaKKalajaSSelanneHRonkainenNJNurmiJEA new perspective on adolescent athletes’ transition into upper secondary school: a longitudinal mixed methods study protocolCogent Psychol201631115

- VerkooijenKTvan HovePDikGAthletic identity and well-being among young talented athletes who live in a Dutch elite sport centerJ Appl Sport Psychol2012241106113

- LemyrePNHallHKRobertsGCA social cognitive approach to burnout in elite athletesScand J Med Sci Sports20081822123417617173

- FrankRNixdorfIBeckmannJDepression among elite athletes: prevalence and psychological factorsDtsch Z Sportmed2015 Available at: http://www.zeitschrift-sportmedizin.de/fileadmin/content/Englische_Artikel/Originalia_Frank_englisch.pdfAccessed July 18, 2016

- HamerMStamatakisESteptoeADose-response relationship between physical activity and mental health: the Scottish health surveyBr J Sports Med200943141111111418403415

- DaleyAExercise and depression: a review of reviewsJ Clin Psychol Med Settings200815214014719104978

- GulliverAGriffithsKMChristensenHInternet-based interventions to promote mental health help-seeking in elite athletes: an exploratory randomized controlled trialJ Med Internet Res2012143e6922743352

- GulliverAGriffithsKMChristensenHBarriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: a qualitative studyBMC Psychiatry20121215723009161

- HammondTGialloretoCKubasHHap DavisHThe prevalence of failure-based depression among elite athletesClin J Sport Med201323427327723528842

- LeddyMHLambertMLOglesBMPsychological consequences of athletic injury among high-level competitorsRes Q Exerc Sport19946543473547886284

- ManuelJCShiltJSCurlWWCoping with sports injuries: an examination of the adolescent athleteJ Adolesc Health200231539139312401424

- JayanthiNPinkhamCDugasLPatrickBLabellaCSports specialization in young athletes: evidence-based recommendationsSports Health20135325125724427397

- BompaTFrom Childhood to Champion AthleteToronto, CanadaVeritas Publishing, Inc1995

- BaryninaIIVaitsekhovskiiSMThe aftermath of early sports specialization for highly qualified swimmersFitness Sports Rev Int199227132133

- WallMCoteJDevelopmental activities that lead to dropout and investment in sportPediatr Exerc Sci20071217787

- ButcherJLindnerKJJohnsDPWithdrawal from competitive youth sport: a retrospective ten-year studyJ Sport Behav2002252145163

- LawMCoteJEricssonKACharacteristics of expert development in rhythmic gymnastics: a retrospective studyInt J Exerc Sport Psychol20075182103

- GouldDUdryETuffeySLoehrJBurnout in competitive junior tennis players: a quantitative psychological assessmentSport Psychol1996104322340

- BudgettRFatigue and underperformance in athletes: the overtraining syndromeBr J Sports Med19983221071109631215

- SmallEChronic musculoskeletal pain in young athletesPediatr Clin North Am200249365566212119870

- O’ConnerPJMorganWPRaglinJSBarksdaleCMKalinNHMood state and salivary cortisol levels following overtraining in females swimmersPsychoneuroendocrinology19891443033102813655

- NixdorfIFrankRHautzingerMBeckmannJPrevalence of depressive symptoms and correlating variables among German elite athletesJ Clin Sport Psychol201374313326

- SteinackerJMBrickMSimschCThyroid hormones, cytokines, physical training and metabolic controlHorm Metab Res200537953854416175490

- Ariza-VargasLDominguez-EscribanoMLopez-BedoyaJVernetta-SantanaMThe effect of anxiety on the ability to learn gymnastic skills: a study based on the schema theorySport Psychol2011252127143

- MakiBEMcIlroyWEInfluence of arousal and attention on the control of postural swayJ Vestib Res19966153598719510

- KoltGSKirkbyRJInjury, anxiety, and mood in competitive gymnasticsPercept Mot Skills19947839559628084718

- AppletonPRHillAPPerfectionism and athlete burnout in junior elite athletes: the mediating role of motivation regulationsJ Clin Sport Psychol201262129145

- AppletonPRHallHKHillAPRelations between multidimensional perfectionism and burnout in junior-elite male athletesPsychol Sport Exerc2009104457465

- Terry-ShortLAOwensRGSladePDDeweyMEPositive and negative perfectionismPers Indiv Differ1995185663668

- FlettGLHewittPLThe perils of perfectionism in sports and exerciseCurr Dir Psychol20051411418

- FrostROHendersonKJPerfectionism and reactions to athletic competitionJ Sport Exerc Psychol1991134323335

- DunnJGHDunnJCGotwalsJKVallanceJKHCraftJMSyrotuikDGEstablishing construct validity evidence for the Sport Multidimensional Perfectionism ScalePsychol Sport Exerc200675759

- GouldDLauerLRoloCJannesCPennisiNUnderstanding the role parents play in tennis success: a national survey of junior tennis coachesBr J Sports Med200640763263616702176

- ShieldsDLBredemeirBLLaVoiNMPowerFCThe sport behavior of youth, parents, and coaches: the good, the bad, and the uglyJ Res Character Educ2007314359

- KidmanLMackenzieAMackenzieBThe nature and target of parental comments during youth sports competitionsJ Sport Behav19992215468

- BlomLCDraneDParents’ sideline comments: exploring the reality of a growing issueAthletic Insight2008103 Available from: http://www.athleticinsight.com/Accessed July 18, 2016

- VincentMAMcCabeMPGender differences among adolescents in family, and peer influences on body dissatisfaction, weight loss, and binge eating behaviorsJ Youth Adolesc2000292205221

- PikeKMRodinJMothers, daughters, and disordered eatingJ Abnorm Psychol199110021982042040771

- BlackmerVSearightHRRatwikSHThe relationship between eating attitudes, body image, and perceived family-of-origin climate among college athletesN Am J Psychol2011133435446

- FranciscoRAlarcaoMNarcisoIAesthetic sports as high risk contexts for eating disorders: young elite dancers and gymnasts perspectivesSpan J Psychol201215126527422379716

- KerrGStirlingAParents’ reflections on their child’s experiences of emotionally abusive coaching practicesJ Appl Sport Psychol2012242191206

- StirlingEA2011Initiating and sustaining emotional abuse in the coach-athlete relationship: athletes’, parents’, and coaches’ reflections Available at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/35742/3/Stirling_Ashley_E_201106_PhD_thesis.pdfAccessed July 18, 2016

- GlaserDEmotional abuse and neglect (psychological maltreatment): a conceptual frameworkChild Abuse Negl2002266–769771412201163

- AlexanderKStaffordALewisRThe experiences of children participating in organized sport in the UK, Edinburgh University of Edinburgh/NSPCC2011 Available at: http://www.nspcc.ork/uk/Inform/research/findings/experiences_children_sport_main_report_wdf85014.pdfAccessed July 18, 2016

- Huffington PostDominique Moceanu talks body image in gymnastics, says coaches can “scar for life” Available at: http://www.huffington-post.com/2013/07/19/dominique-moceanu-body-im_n_3625224.htmlAccessed July 18, 2016