Abstract

Microbial keratitis (MK) is a corneal condition that encompasses several different pathogens and etiologies. While contact lens associated MK is most often associated with bacterial infections, other pathogens (fungi, Acanthamoeba species, etc) may be responsible. This review summarizes the risk factors, microbiology, diagnostic characteristics, and treatment options for all forms of contact lens-related MK.

Introduction

There are approximately 38 million individuals wearing contact lenses in the United States.Citation1 Contact lens wear significantly increases the risk of ocular complications, specifically microbial keratitis (MK), which is the most severe complication and is vision threatening.Citation2 MK is a term that includes bacterial keratitis (BK), fungal keratitis (FK), and Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) (). Geographically, the causes of MK differ. In non-Westernized countries, trauma is the leading cause of MK,Citation3,Citation4 whereas in Westernized countries, contact lens wear is equal to or often exceeds trauma as the most significant cause.Citation5–Citation7 This review describes the incidence, risk factors, and pathogenesis of contact lens associated MK and the practitioner’s role in properly diagnosing, culturing, and managing these severe complications.

Table 1 Types of microbial keratitis and the primary risk factors for acquiring these infections in Westernized countries

Incidence

The first large epidemiological study on contact lens-related MK was published in 1989, and the incidence rate of MK among individuals wearing lenses in the daily wear modality was 4.1 per 10,000 individuals per year ().Citation8 In 2008, Stapleton et al reported an annual MK incidence rate in daily wear of 1.9 per 10,000 wearers,Citation9 which is consistent with other studies.Citation10–Citation12

Table 2 Annual incidence of contact lens-related bacterial, fungal, and protozoan keratitis

Compared with daily wear, overnight (extended wear, EW) use of soft contact lenses is associated with a higher risk of MK. EW, irrespective of material type, has been shown to be the primary factor for corneal infection with an annual incidence of approximately 20 per 10,000.Citation9,Citation13 Interestingly, sporadic or occasional EW has been shown to be a more significant MK risk factor than continuous wear.Citation14 The introduction of highly oxygen-permeable silicone hydrogel materials has not provided the anticipated decrease in MK associated with EW. The incidence of MK and corneal inflammatory eventsCitation15 with silicone hydrogel EW has been shown to be the sameCitation14,Citation16 or greaterCitation17 than lower oxygen permeability hydrogel materials. While silicone hydrogel materials reduce hypoxia-related complications, they do not eliminate exposure to pathogenic organisms. It has been suggested that silicone hydrogel materials may alter epithelial homeostasis, resulting in mechanical stress that makes the cornea more susceptible to inflammatory and/or infectious events.Citation17

The incidence of MK with gas-permeable (GP) materials ranges between 0.8Citation10 and 4.0Citation8 per 10,000 per year. These reported rates included both daily wear and EW. Orthokeratology, a form of GP lens vision correction, involves wearing lenses overnight to reshape the cornea and correct myopia. The annual rate of MK associated with orthokeratology is estimated to be 7.7 per 10,000.Citation18 In Asian countries, orthokeratology-related MK has been shown to be most common in areas with more prevalent myopia.Citation19 It has been suggested that this higher prevalence may be due to poor regulation in these areas.Citation20 Regardless of wearing soft or GP contact lenses, EW significantly increases the risk of contracting MK compared with daily wear.

Risk factors

MK in contact lens wearers is typically associated with non-compliant or unhygienic contact lens practices. Many of these risky behaviors which include EW,Citation2,Citation8–Citation10 poor storage case hygiene and infrequent case replacement,Citation9,Citation21,Citation22 smoking,Citation2,Citation8–Citation10,Citation23 lack of hand washing,Citation10 and purchasing lenses on the internetCitation9 are all modifiable. Nonmodifiable risk factors are wearing lenses for less than 6 months,Citation9 male sex,Citation8,Citation24 socioeconomic status,Citation9 and possibly a genetic predisposition.Citation25,Citation26

Lens-related MK risk factors include cosmetic lenses, as these lenses are often not prescribed by an eye care professional and therefore, patients have less knowledge of proper lens care.Citation27 Daily disposable lenses do not eliminate the risk of MK,Citation9,Citation13 however, there may be a lower risk of vision loss when compared with planned replacement.Citation9,Citation13 The type of contact lens disinfection system used has been found to modify the risk of MK,Citation28 and specific brands were responsible for the FKCitation29 and AKCitation30 outbreaks.

FK and AK cases have additional risk factors that need to be ruled out when MK is present. FK associated with vegetative trauma and/or ocular surface disease is most common in tropical and subtropical climates.Citation31,Citation32 Trauma or corneal compromise caused by contact lens wear has also been suggested as a risk factor.Citation31,Citation33 Candida species tend to infect corneas that are comprised due to ocular surface disease and/or systemic immunodeficiencyCitation31,Citation34 and are more common in temperate climates.Citation31,Citation34

Acanthamoeba associated MK, while relatively rare,Citation35 often results in severe vision loss due to misdiagnosis.Citation36 Because of the frequent misdiagnosis of this condition, longer duration of symptoms and history of antibiotic use have been listed as risk factors.Citation36 As mentioned above, exposure to infected water is a well-known risk factor for Acanthamoeba infection.Citation28 This exposure may occur when contact lenses are cleaned/stored in tap water, or when a patient is exposed to bodies of water that could be infected (lakes, hot tubs, etc).Citation28,Citation37

Pathogenesis

Inherent protective mechanisms and contact lens-induced alterations

A healthy corneal surface is not susceptible to microbial infection. Chronic ocular surface disease, corneal trauma, ocular surgery, and contact lens wear increase the cornea’s susceptibility to infection. The mechanisms of contact lens-related corneal infection are not fully understood; however, several models exist for bacterial, fungal, and protozoan infections.

The non-contact lens exposed cornea easily resists microbes from “sticking” to the ocular surface through several inherent protective mechanisms employed by the tear fluid and corneal epithelium.Citation38 The tear fluid, along with blinking, clears pathogens from the cornea and contains antimicrobial components such as lysozyme and lactoferrin.Citation39 The epithelial cells also produce peptides and mucins that are inherently antimicrobial.Citation40 The epithelial tight junctions serve as a physical barrier to microbes, however, even when the superficial junctions are damaged, Pseudomonas cannot traverse the protective anterior limiting lamina (Bowman’s membrane) to the stroma.Citation41 This suggests that superficial fluorescein staining does not lead to MK.Citation42

Contact lens wear disrupts some of these innate defenses and renders the cornea more susceptible to infection. Lens wear, regardless of oxygen transmissibility, has been shown to decrease epithelial mitosis, differentiation,Citation43 and exfoliation.Citation44 These processes create a stagnant epithelium and render the cornea more susceptible to infection. Hypoxic conditions have been shown to decrease epithelial exfoliation, but hypoxia alone does not increase Pseudomonas binding.Citation45 Hypoxia can lead to increased Pseudomonas corneal binding, but only when a contact lens is also present.Citation46

Contact lens wear has also been shown to mechanically damage the epithelium, resulting in punctate epithelial erosions.Citation47 Interestingly, though the surface damage is worse with a GP, there is increased Pseudomonas epithelial binding with soft lenses from reduced tear exchange beneath the contact lens.Citation47 Planktonic, or free floating, bacteria adhere to the surface of the contact lens and can form virulent biofilms which are less susceptible to the normal antimicrobial defense mechanisms of the tears and epithelium.Citation42 Biofilms on the posterior contact lens surface place bacteria in close proximity to the epithelium and these microbes cannot be easily cleared away, creating a stagnant tear environment.Citation48

Bacterial keratitis model

The majority of contact lens-related bacterial ulcers are due to Pseudomonas,Citation6,Citation49 and the stagnant post-lens tear environment may allow for Pseudomonas to “stick” to the corneal epithelium which must happen in order for an infection to develop.Citation50 Pseudomonas adheres to the corneal epithelium via specific receptors expressed on the outer cell membrane.Citation51 Specific to Pseudomonas, there is an invasive phenotype, exoenzyme S (exoS) gene, and a cytotoxic phenotype, exoenzyme U (exoU) gene. The invasive form enters epithelial cells via lipid rafts, replicates intracellularly, and eventually causes host cell death.Citation50 Interestingly, the presence of Pseudomonas alone does not trigger lipid raft development, but a low oxygen transmissible lens also is necessary. The cytotoxic phenotype is associated with severe corneal inflammation and tissue damage due to the extracellular injection of a potent cytoxin.Citation52 Choy et al suggested that with contact lens wear, the cytoxic phenotype is isolated more often than the invasive phenotype;Citation53 however, a recent article suggests otherwise.Citation54

Regardless of the phenotypes listed above, Pseudomonas species have additional virulence factors such as adhesins,Citation55 flagella,Citation56 several forms of toxins,Citation57 and have even been capable of metabolizing some antibiotics.Citation58 They also employ auxiliary genetic code in the form of plasmids.Citation57 These factors allow the bacterium to be extremely dynamic and potentially evade host defense mechanisms which compounds tissue damage and can result in worse visual outcomes.

Fungal keratitis model

In the United States, FK most often occurs from agricultural related trauma, contact lens wear, and ocular surface disease.Citation59 Filamentous fungi, such as Fusarium and Aspergillus, tend to be most often associated with contact lens wear and trauma, while those with ocular surface disease are more prone to yeasts.Citation59

Contact lens-related FK likely results from fungal biofilms, which can be firmly attached to the posterior side of the lens or even extend into the lens matrix.Citation60 Using a murine model, it has been shown that hyphae from Fusarium or Aspergillus in contact with the corneal epithelium may disrupt epithelial integrity.Citation61 If the epithelial integrity is affected, then hyphae have the capability of breaching the basement membrane and the anterior limiting lamina and ultimately reaching the stroma.Citation62 Once in the stroma, the hyphae can continue to extend through the stroma and in some cases can perforate the cornea reaching the anterior chamber.Citation62 The extending hyphae result in the feathery border appearance that is classically seen with FK.Citation62 Neutrophils are recruited to the site and release proteolytic enzymesCitation61 and reactive oxygen speciesCitation64 which eradicate the fungus, but can also cause substantial collateral tissue damage. The cumulative inflammation may also trigger the development of a hypopyon and an endothelial plaque.Citation59,Citation62

Acanthamoeba keratitis model

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Acanthamoeba is commonly found in soil, water, and air.Citation65 Contact lens-wearing individuals who expose their lenses to water through swimming, hot tubs, trauma with contaminated water, or care for their lenses with water are at greater risk of infection.

The largest risk factor for contact lens-related AK is poor compliance with lens care which leads to subsequent biofilm formation.Citation66 These biofilms, such as those formed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa provide a nutrient-rich environment for Acanthamoeba trophozoites to thrive.Citation66 Once Acanthamoeba is present on the surface of the contact lens, the cornea is at increased risk of infection.Citation66 Khan et al found that for Acanthamoeba to bind to and develop a corneal infection, a previous insult to the epithelial tissue must be present.Citation67 Omana-Molina et al have recently found that Acanthamoeba are actually capable of binding to intact epithelium.Citation68

Acanthamoeba trophozoites are likely present during epithelial binding, because the cystic form shows minimal binding capability.Citation69 The trophozoites adhere to the epithelium using mannose-binding proteinCitation70 and other laminin-binding proteins.Citation69 Contact lenses have been shown to stimulate glycoprotein expression,Citation71 and the mannose-binding protein may have greater tendency to bind to the epithelium.Citation72 Once bound to the corneal epithelium, the trophozoites use phagocytosis for nutrition and secrete toxins, such as serine proteases, collagenases, and stimulate the activity of cytotoxic matrix metalloproteinases, which creates a cytopathic effect.Citation73 The cytopathic effect includes killing host cells by phagocytosis, apoptosis, or cytolysis, followed by degradation of the epithelial basement membrane and anterior limiting lamina, and subsequent migration into the corneal stroma. Interestingly, Acanthamoeba does not typically breach the corneal endotheliumCitation74 and this is thought to be due to an intense response from neutrophils.Citation75

When the trophozoites experience a change in pH, temperature, lack of nutrition, or chemicals they can form double-walled cysts.Citation76 Cysts are very difficult to treat and have been found in postinfected corneas 31 months after onset and in some cases likely longer.Citation77 The corneal infection is not truly gone until all the trophozoites and cysts have been removed from the cornea.Citation77

Diagnosis

Patient history

Proper diagnosis of MK is based on a combination of patient symptoms, pertinent ocular history, clinical examination, and culturing. The patient’s history and symptoms provide us valuable clues regarding the etiology of the keratitis. Trauma due to vegetative debris often is associated with FK while a history of hot tub use or contact with stagnant water suggests AK. Patients with a history of contact lens wear are at risk for any form of MK and should be further questioned to elucidate potential risk factors such as overnight wear, poor contact lens, or case hygiene, swimming in contact lenses, or using water for cleaning, disinfection, or storage.

Bacterial keratitis

Individuals with BK will often experience significant pain, photophobia, and likely enter the clinic with reduced visual acuity (). The onset of symptoms often occurs quickly. There are several common slit lamp characteristics found with BK. A corneal infiltrate, or multiple corneal infiltrates are found in every case, while the size of the infiltrate can vary dramatically.Citation5 An infiltrate that is greater than or equal to 1 mm in width is often considered infectious.Citation78 Depending on the severity of the infection, infiltrate depth can vary with the majority (77%) being confined to the anterior one-third of the stroma.Citation5 The epithelium overlying the infiltrate is often absent, and the tissue may appear slightly excavated.Citation79 A noninfectious ulcer often has an overlying staining area that is smaller than the infiltrate diameter.Citation79 Anterior chamber inflammation may be present with hypopyon developing between 6.1%Citation5 and 55%Citation36 of the time. The bulbar conjunctiva is often diffusely injected, and the discharge can range from a watery to a mucopurulent consistency.Citation79 In addition to the ocular surface changes, the eyelids may also be edematous.Citation79

Table 3 Clinical characteristics of the different forms of microbial keratitis

Fungal keratitis

The patient history and onset of symptoms is essential when diagnosing FK. Fungi need time to grow, so symptoms may be delayed for 5–10 days.Citation62 AK and BK typically will have a faster onset of symptoms.

The clinical appearance of FK depends on whether the infection is due to filamentous fungi such as Fusarium and Aspergillus or a yeast such as Candida. Corneal infections due to Candida often resemble BK as there is a round or ovalish epithelial defect with surrounding inflammation.Citation80 Mycotic keratitis due to Fusarium or Aspergillus will be associated with “feathery” edges, elevated slough,Citation62,Citation81 and satellite infiltrates.Citation82 A hypopyon can developCitation81 as can an endothelial plaque.Citation83 Thomas et al compared the slit lamp signs of patients with fungal and BK, and found that serrated margins, raised slough, and satellite lesions were more often associated with FK, whereas BK had a greater frequency of hypopyon and anterior chamber flare.Citation81

Acanthamoeba keratitis

The classic clinical signs of AK are a ring infiltrate and perineuritis;Citation84–Citation86 however, the clinician must understand that these signs are not always present. Two recent retrospective studies have found that perineuritis was present in 20.7%Citation85 and 21.6%,Citation86 whereas the ring infiltrate was found in 27.6%Citation85 and 29.3%.Citation86 The early clinical signs tend to be a nonspecific epitheliopathy, pseudo-dendrites, subepithelial infiltrates, and in some cases perinueral infiltrates.Citation84,Citation85 As the disease progresses, the progression to a ring infiltrate and uveitis are more likely to be identified.Citation84 If the disease is diagnosed early, usually within the first few weeks, the disease can be confined to the epithelium or anterior stroma and visual outcomes are substantially better compared with a late diagnosis.Citation85

Confocal microscopy is a technique that has been shown to assist with diagnosing the condition.Citation86 Hau et al presented confocal microscopy images from culture positive specimens to cornea specialists masked to the tissue diagnosis and asked them to provide a clinical diagnosis.Citation87 Relying on confocal microscopy alone resulted in a sensitivity range of 27.9%–55.8% and specificity range of 42.1%–84.2%.Citation87 When using confocal microscopy in addition to clinical characteristics and objective findings, Tu et al found the sensitivity to be 90.6% and a specificity of 100%.Citation88 Confocal microscopy alone is not reliable enough to diagnose AK, but when combined with clinical findings and culturing (positive culture rates are as high as 88%), it can aid in properly diagnosing the condition.Citation86

Treatment

Bacterial keratitis

Due to the inherent delay in accessing culture results, the clinician must initiate treatment empirically. Studies have shown that a single fluoroquinolone is as effective as fortified preparations in treating BK.Citation89–Citation91 It should be noted that only ciprofloxacin 0.3%, ofloxacin 0.3%, and levofloxacin 1.5% have US Food and Drug Administration approval for treating BKCitation92 although use of fourth generation fluoroquinolones as monotherapy is quite common.Citation89 Due to increased microbial resistance to fluoroquinolones,Citation93 specifically with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus,Citation94 some advocate for initial empirical monotherapy use of the chlorofluoroquinolone, besifloxacin 0.6%.Citation95,Citation96 If methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is identified through culturing or Gram stain, the treatment may be modified to include a more potent agent such as fortified vancomycin.Citation97

The antibiotic must be applied to the ocular surface frequently. In two studies, the initial treatment consisted of a drop every hour around the clock.Citation4,Citation89 With severe ulcers the eye drops can be instilled every 5–15 minutes for first hour followed by hourly or half-hourly application.Citation92 BK resolution depends on the initial size of the ulcer, but most re-epithelialize within 3.5–7 days.Citation98

In addition to an antibiotic, a cycloplegic agent can be used to minimize photophobia and risk of posterior synechiae.Citation92 The role of corticosteroids with BK is more controversial and the Steroids for Corneal Ulcer study found no improvement in clinical outcome in the steroid group versus the placebo group.Citation99 Although there was no overall benefit, there was also no evidence of a reduced visual outcome.Citation99 When limiting the sample to only the most severe cases, steroids did provide a slight clinical benefit.Citation99 For the clinician, if BK is suspected, the application of a steroid should only commence if clinical signs are improving, which suggests that the selected antibiotic is effective against the offending microbe.

Fungal keratitis

The only US Food and Drug Administration approved ophthalmic antifungal medication is 5% natamycin, which is commercially labeled as Natacyn (Alcon Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA). A recent worldwide survey on FK treatment practice patterns found that natamycin is the most frequently used antifungal for filamentous fungi.Citation100 Amphotericin and voriconazole were the next most common. For infections caused by yeast, amphotericin was the most common followed by natamycin.Citation100 Overall, respondents reported use of oral antifungals “always” (10%), “most of the time” (27%), “sometimes” (55%), and “never” (8%).Citation100

Natamycin and amphotericin are polyenes which irreversibly bind to ergosterol and increase fungal cell wall permeability.Citation101 Voriconazole is a triazole, and this inhibits ergosterol synthesis.Citation100 The Mycotic Ulcer Treatment Trial compared the performance of these two medications and found that natamycin overall had better visual outcomes and faster resolution when compared with voriconazole.Citation102 For Fusarium keratitis, natamycin significantly improved vision outcomes and reduced the risk of perforation. For non-Fusarium FK, the two medications performed similarly.Citation102

Acanthamoeba keratitis

There are no approved amoebicidal agents at this time.Citation84 The typical medications used for AK can include biguanides or diamidines. The two biguanide agents are polyhexamethylene biguanide 0.02%–0.06% and chlorhexidine 0.02%–0.2%.Citation84 Biguanides damage the cytoplasmic membrane which results in a loss of cellular components.Citation84 The diamidines induce structural changes to the cellular membrane altering permeability,Citation84 and the typical agents are propamidine 0.1% and hexamidine 0.1%. Some centers still use neomycin, but not as monotherapy.Citation85,Citation103 The vast majority of corneal specialists (93.9%) use a combination of agents.Citation104 Oral voriconazole, an antifungal, can have an ameobicidal effect by binding ergosterol – which is present in the cell membrane of fungi and Acanthamoeba.Citation105 Steroids are reportedly used during the course of Acanthamoeba treatment, but their role is controversial.Citation104

Nonpharmaceutical treatments for MK cases that are not responding to topical medication can include penetrating or lamellar keratoplasties of the infected cornea,Citation106 which are known as “hot corneal grafts”. The use of corneal cross-linking for MK is becoming more commonCitation107–Citation109 and can be effective in eradicating offending microbes. Amniotic membranes can also be used to augment pharmaceutical treatment.Citation110

Culturing

Knowing when to culture a corneal lesion often times is not intuitive. Some advocate for culturing any corneal lesion, whereas the majority of ophthalmologists reserve culturing for lesions meeting specific criteria.Citation111 According to the 2013 American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) Preferred Practice Patterns for Bacterial Keratitis, culturing only needs to be performed for ulcers that are deep, large, an atypical presentation, having questionable history or unresponsive to initial treatment.Citation92 A recent survey, performed by Park et al, provides a glimpse of corneal culture procedures performed by ophthalmologists in the United States.Citation111 Only 8.6% of ophthalmologists felt that it was necessary to always culture a lesion.Citation111 Fifty-eight percent of the cases seen by corneal specialists are cultured versus 22% by noncorneal specialists.Citation111 Overall, corneal specialists were more likely to culture, and all respondents were more likely to culture with unresponsive lesions, deep infiltrates, or atypical lesions. The practice patterns identified in the Park survey align well with the AAO corneal culturing guidelines.

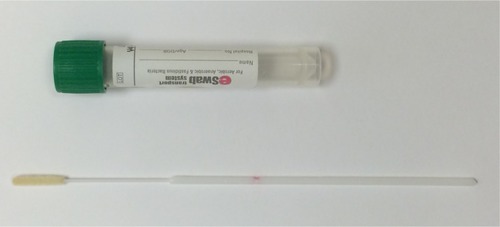

Tertiary referral centersCitation36,Citation93,Citation112 likely will have complete culturing supplies which include chocolate agar, blood agar, thioglycolate broth, brain–heart infusion broth, Sabouraud’s dextrose agar, and nonnutrient agar with overlying Escherichia coliCitation113 (). For nontertiary referral centers, having access to transport swabs for culturing may be more prudent. The ESwab (Copan Diagnostics, Murrieta, CA, USA) uses a flocked nylon tip () which allows for increased fluid uptake and enhances specimen release.Citation114 ESwabs have a shelf life of 18 months without refrigeration and they provide enhanced microbial uptake and release when compared with traditional swabs.Citation115 ESwabs were compared with direct platingCitation115 and found to provide positive cultures 69% of the time while direct plating yielded positive cultures 70% of the time.

Table 4 Culture yields obtained from the cornea and contact lens paraphernalia

Once a swab is used to collect microbes, the swab needs to be delivered to a microbiology lab for processing. The ESwabs have been shown to provide viable specimens for several microbes even after 48 hours.Citation116 Refrigeration of the sample improves the recovery viability for Neisseria gonorrhoeae at 48 hours. Pseudomonas, the most common isolate in contact lens-related BK, can be recovered with or without refrigeration at 48 hours.Citation116

Not all cultures yield positive results (), and the information obtained from cultures is not instantly available, so the clinician must begin treatment empirically. Once the culture is obtained, the topical therapy can be adjusted if the prescribed antimicrobial is ineffective against the offending microbe. If the corneal lesion is unresponsive to therapy, a referral to a corneal specialist should be initiated. The corneal specialist may need to obtain additional corneal scrapings for Gram stains or perform a corneal biopsy to be sent for culture and histopathological analysis.Citation92 Gram stains obtained from corneal scrapings have been shown to be more sensitive than culturing for detecting fungus and protozoans in infectious keratitis cases.Citation117 Scrapings should occur for both suspected FK, AK, and nonresolving BK. Specific to Acanthamoeba, scraping should occur, regardless of whether it is early or late in the disease process.Citation85

In addition to culturing the cornea, contact lenses and their storage cases can provide positive cultures (). Positive culture yields from the contact lenses of patients with MK range from 67%Citation118 to 92%,Citation119 while positive yields from storage cases are as high as 80%–85%.Citation119,Citation120 Culture positive cases are common in healthy contact lens wearers and do not always lead to MK. However, studies have shown a high species concordance between the cultures obtained from the corneas, contact lenses, and storage cases of patients with MK. Martins et al found that when the corneal cultures were positive, the species concordance with lens paraphernalia was 100% for FK, 80% for AK, and 74.5% for BK.Citation121 Konda et al also demonstrated that when corneal cultures were negative, but microbes were obtained from the lens paraphernalia, that the isolated microbe likely was the infectious agent.Citation119

Microbiology

Although culture yields vary among studies, often times the identified isolates are the same. For contact lens-related BK, the most frequently isolated organism tends to be the Gram-negative species, P. aeruginosaCitation5,Citation10,Citation122 (). Another commonly identified Gram-negative organism is Serratia spp. Rivaling Pseudomonas for the most commonly isolated bacteria associated with contact lens-related BK is the Gram-positive commensal organism, coagulase-negative Staphylococci.Citation5,Citation112,Citation123 Gram-negative species tend to be more virulent and are associated with worse visual outcomes compared with Gram-positive microbes.Citation7

Table 5 Common microorganisms responsible for contact lens-related microbial keratitis

FK accounts for approximately 5% of all contact lens-related MK.Citation6,Citation10 The most common isolates are the filamentous organisms, Fusarium and Aspergillus. These two species account for between 62% and 77% of cases with the majority of cases due to Fusarium.Citation124 Yeast, or molds, such as Candida spp, make up approximately 10% of contact lens-related FK cases.

AK comprises between 0.9% and 4% of contact lens-related MK.Citation7,Citation11,Citation119 There are eight Acanthamoeba species that have been identified in patients with keratitis. The most common species related to keratitis are Acanthamoeba castellaniiCitation125 and Acanthamoeba polyphaga.Citation84,Citation126 Although it is important to attempt to identify the offending amoeba, regardless of the species, the treatment will be the same.Citation84

Morbidity/visual outcomes/cost

Of the three forms of MK, AK is the most worrisome and costly (). Keay et al estimate that the average cost of treatment (in 2006) was over US$5,500Citation7 with the mean duration of treatment lasting between 140 days and 18 months.Citation103,Citation127,Citation128 The worst visual outcomes tend to be cases with delayed diagnosis or those exposed to topical steroids.Citation85,Citation86 If diagnosed and treated early, visual outcomes are substantially better than a delayed diagnosis.Citation85,Citation86

About 30% of resolved contact lens FK result in visual acuity of worse than 20/30.Citation129 In a multicenter analysis of FK in the United States, those with contact lens-related FK had a penetrating keratoplasty rate of approximately 17%.Citation124 Fortunately, if diagnosed early, there are effective medications, and time to resolution is approximately 1 month.Citation130

BK tends to have less severe outcomes compared with AK or FK, but certainly can be visually devastating with one study showing a penetrating keratoplasty rate of approximately 13%.Citation131 Most studies show PK rates of less than 13%Citation9 and visual acuity loss (worse than 20/30) associated with contact lens-related BK has been reported to be around 14%.Citation9

Conclusion

The incidence of contact lens-related MK has not significantly changed since 1989. Some believe the incidence of MK, particularly AK is increasing.Citation132,Citation133 Eye care practitioners play an important role in diagnosing and managing cases of MK. While it is unlikely that an optometrist or a general ophthalmologist will be actively treating severe MK, it is important to recognize the clinical signs and symptoms early in the course of these diseases in order to refer for appropriate care quickly.

When fitting or evaluating contact lenses, the eye care practitioner must discuss the risks of contact lens wear and the need for proper lens replacement and disinfection with their patients. Improved and persistent patient education will hopefully help to decrease the incidence of MK.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NicholsJJContact lenses 2014Contact Lens Spectrum20153012227

- DartJKStapletonFMinassianDContact lenses and other risk factors in microbial keratitisLancet199133887686506531679472

- FurlanettoRLAndreoEGFinottiIGArcieriESFerreiraMARochaFJEpidemiology and etiologic diagnosis of infectious keratitis in Uberlandia, BrazilEur J Ophthalmol201020349850320175055

- ShahVMTandonRSatpathyGRandomized clinical study for comparative evaluation of fourth-generation fluoroquinolones with the combination of fortified antibiotics in the treatment of bacterial corneal ulcersCornea201029775175720489580

- BourcierTThomasFBorderieVChaumeilCLarocheLBacterial keratitis: predisposing factors, clinical and microbiological review of 300 casesBr J Ophthalmol200387783483812812878

- GreenMApelAStapletonFRisk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitisCornea2008271222718245962

- KeayLEdwardsKNaduvilathTFordeKStapletonFFactors affecting the morbidity of contact lens-related microbial keratitis: a population studyInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci200647104302430817003419

- PoggioECGlynnRJScheinODThe incidence of ulcerative keratitis among users of daily-wear and extended-wear soft contact lensesN Engl J Med1989321127797832770809

- StapletonFKeayLEdwardsKThe incidence of contact lens-related microbial keratitis in AustraliaOphthalmology2008115101655166218538404

- LamDSHouangEFanDSIncidence and risk factors for microbial keratitis in Hong Kong: comparison with Europe and North AmericaEye200216560861812194077

- ChengKHLeungSLHoekmanHWIncidence of contact-lens-associated microbial keratitis and its related morbidityLancet1999354917418118510421298

- SealDVKirknessCMBennettHGPetersonMKeratitis StudyGAcanthamoeba keratitis in Scotland: risk factors for contact lens wearersCont Lens Anterior Eye1999222586816303407

- DartJKRadfordCFMinassianDVermaSStapletonFRisk factors for microbial keratitis with contemporary contact lenses: a case-control studyOphthalmology200811510164716541654.e1641e164318597850

- ScheinODMcNallyJJKatzJThe incidence of microbial keratitis among wearers of a 30-day silicone hydrogel extended-wear contact lensOphthalmology2005112122172217916325711

- Szczotka-FlynnLDiazMRisk of corneal inflammatory events with silicone hydrogel and low dk hydrogel extended contact lens wear: a meta-analysisOptom Vis Sci200784424725617435508

- StapletonFKeayLEdwardsKHoldenBThe epidemiology of microbial keratitis with silicone hydrogel contact lensesEye Contact Lens2013391798523172318

- RobertsonDMThe effects of silicone hydrogel lens wear on the corneal epithelium and risk for microbial keratitisEye Contact Lens2013391677223266590

- BullimoreMASinnottLTJones-JordanLAThe risk of microbial keratitis with overnight corneal reshaping lensesOptom Vis Sci201390993794423892491

- ChanTCLiEYWongVWJhanjiVOrthokeratology-associated infectious keratitis in a tertiary care eye hospital in Hong KongAm J Ophthalmol2014158611301135.e113225158307

- WattKGSwarbrickHATrends in microbial keratitis associated with orthokeratologyEye Contact Lens2007336 Pt 2373377 discussion 38217975424

- GrayTBCursonsRTSherwanJFRosePRAcanthamoeba, bacterial, and fungal contamination of contact lens storage casesBr J Ophthalmol19957966016057626578

- HouangELamDFanDSealDMicrobial keratitis in Hong Kong: relationship to climate, environment and contact-lens disinfectionTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg200195436136711579873

- MorganPBEfronNBrennanNAHillEARaynorMKTulloABRisk factors for the development of corneal infiltrative events associated with contact lens wearInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20054693136314316123412

- StapletonFDartJKMinassianDRisk factors with contact lens related suppurative keratitisCLAO J19931942042108261602

- CarntNAWillcoxMDHauSImmune defense single nucleotide polymorphisms and recruitment strategies associated with contact lens keratitisOphthalmology2012119101997200222809755

- CarntNAWillcoxMDHauSAssociation of single nucleotide polymorphisms of interleukins-1beta, -6, and -12B with contact lens keratitis susceptibility and severityOphthalmology201211971320132722503230

- SauerABourcierTFrench Study Group for Contact Lenses Related MicrobialKMicrobial keratitis as a foreseeable complication of cosmetic contact lenses: a prospective studyActa Ophthalmol2011895e439e44221401905

- RadfordCFBaconASDartJKMinassianDCRisk factors for acanthamoeba keratitis in contact lens users: a case–control studyBMJ19953106994156715707787645

- ChangDCGrantGBO’DonnellKMultistate outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solutionJAMA2006296895396316926355

- VeraniJRLorickSAYoderJSNational outbreak of Acanthamoeba keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution, United StatesEmerg Infect Dis20091581236124219751585

- NielsenSENielsenEJulianHOIncidence and clinical characteristics of fungal keratitis in a Danish population from 2000 to 2013Acta Ophthalmol2015931545824836583

- BharathiMJRamakrishnanRMeenakshiRPadmavathySShivakumarCSrinivasanMMicrobial keratitis in South India: influence of risk factors, climate, and geographical variationOphthalmic Epidemiol2007142616917464852

- TanureMACohenEJSudeshSRapuanoCJLaibsonPRSpectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, PennsylvaniaCornea200019330731210832689

- RitterbandDCSeedorJAShahMKKoplinRSMcCormickSAFungal keratitis at the New York eye and ear infirmaryCornea200625326426716633023

- CDC.gov [homepage on the Internet]Parasites – Acanthamoeba – Granulomatous Amebic Encephalitis (GAE); Keratitis [updated August 24, 2012] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/acanthamoeba/epi.htmlAccessed June 24, 2015

- MascarenhasJLalithaPPrajnaNVAcanthamoeba, fungal, and bacterial keratitis: a comparison of risk factors and clinical featuresAm J Ophthalmol20141571566224200232

- WhitingMARaynorMKMorganPBGallowayPToleDMTulloAContinuous wear silicone hydrogel contact lenses and microbial keratitisEye200418993593715094738

- FleiszigSMMcNamaraNAEvansDJThe tear film and defense against infectionAdv Exp Med Biol2002506Pt A52353012613956

- FlanaganJLWillcoxMDRole of lactoferrin in the tear filmBiochimie2009911354318718499

- EvansDJFleiszigSMWhy does the healthy cornea resist Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection?Am J Ophthalmol20131556961970.e96223601656

- AlarconITamCMunJJLeDueJEvansDJFleiszigSMFactors impacting corneal epithelial barrier function against Pseudomonas aeruginosa traversalInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20115231368137721051692

- TamCMunJJEvansDJFleiszigSMThe impact of inoculation parameters on the pathogenesis of contact lens-related infectious keratitisInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20105163100310620130275

- LadagePMJesterJVPetrollWMBergmansonJPCavanaghHDVertical movement of epithelial basal cells toward the corneal surface during use of extended-wear contact lensesInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20034431056106312601029

- CavanaghHDThe effects of low- and hyper-Dk contact lenses on corneal epithelial homeostasisOphthalmol Clin North Am200316331132514564755

- RenDHPetrollWMJesterJVHo-FanJCavanaghHDShort-term hypoxia downregulates epithelial cell desquamation in vivo, but does not increase Pseudomonas aeruginosa adherence to exfoliated human corneal epithelial cellsCLAO J1999252737910344293

- CavanaghHDLadagePMLiSLEffects of daily and overnight wear of a novel hyper oxygen-transmissible soft contact lens on bacterial binding and corneal epithelium: a 13-month clinical trialOphthalmology2002109111957196912414399

- ImayasuMPetrollWMJesterJVPatelSKOhashiJCavanaghHDThe relation between contact lens oxygen transmissibility and binding of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the cornea after overnight wearOphthalmology199410123713888115159

- FleiszigSMEvansDJContact lens infections: can they ever be eradicated?Eye Contact Lens2003291 SupplS67S71 discussion S83–S84, S192–S19412772735

- StapletonFCarntNContact lens-related microbial keratitis: how have epidemiology and genetics helped us with pathogenesis and prophylaxisEye201226218519322134592

- RobertsonDMPetrollWMJesterJVCavanaghHDThe role of contact lens type, oxygen transmission, and care-related solutions in mediating epithelial homeostasis and pseudomonas binding to corneal cells: an overviewEye Contact Lens2007336 Pt 2394398 discussion 399–40017975430

- FletcherELFleiszigSMBrennanNALipopolysaccharide in adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the cornea and contact lensesInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci1993346193019368491546

- SatoHFrankDWExoU is a potent intracellular phospholipaseMol Microbiol20045351279129015387809

- ChoyMHStapletonFWillcoxMDZhuHComparison of virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from contact lens-and non-contact lens-related keratitisJ Med Microbiol200857Pt 121539154619018027

- BorkarDSFleiszigSMLeongCAssociation between cytotoxic and invasive Pseudomonas aeruginosa and clinical outcomes in bacterial keratitisJAMA Ophthalmol2013131214715323411878

- TangHKaysMPrinceARole of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pili in acute pulmonary infectionInfect Immun1995634127812857890385

- FeldmanMBryanRRajanSRole of flagella in pathogenesis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infectionInfect Immun199866143519423837

- KungVLOzerEAHauserARThe accessory genome of Pseudomonas aeruginosaMicrobiol Mol Biol Rev201074462164121119020

- DantasGSommerMOOluwasegunRDChurchGMBacteria subsisting on antibioticsScience2008320587210010318388292

- GowerEWKeayLJOechslerRATrends in fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001 to 2007Ophthalmology2010117122263226720591493

- ZhangSAhearnDGStultingRDDifferences among strains of the Fusarium oxysporum–F solani complexes in their penetration of hydrogel contact lenses and subsequent susceptibility to multipurpose contact lens disinfection solutionsCornea200726101249125418043184

- SunYChandraJMukherjeePSzczotka-FlynnLGhannoumMAPearlmanEA murine model of contact lens-associated fusarium keratitisInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20105131511151619875664

- ThomasPAFungal infections of the corneaEye200317885286214631389

- LealSMJrPearlmanEThe role of cytokines and pathogen recognition molecules in fungal keratitis – insights from human disease and animal modelsCytokine201258110711122280957

- HuJWangYXieLPotential role of macrophages in experimental keratomycosisInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20095052087209419074808

- Acanthamoeba Keratitis FAQs http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/acanthamoeba/gen_info/acanthamoeba_keratitis.htmlAccessed November 18, 2015

- WalochnikJScheiklUHaller-SchoberEMTwenty years of acanthamoeba diagnostics in AustriaJ Eukaryot Microbiol201562131125047131

- KhanNAAcanthamoeba: biology and increasing importance in human healthFEMS Microbiol Rev200630456459516774587

- Omana-MolinaMAGonzalez-RoblesASalazar-VillatoroLSilicone hydrogel contact lenses surface promote Acanthamoeba castel-lanii trophozoites adherence: qualitative and quantitative analysisEye Contact Lens201440313213924699779

- Lorenzo-MoralesJKhanNAWalochnikJAn update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatmentParasite2015221025687209

- GarateMCaoZBatemanEPanjwaniNCloning and characterization of a novel mannose-binding protein of AcanthamoebaJ Biol Chem200427928298492295615117936

- KlotzSAMisraRPButrusSIContact lens wear enhances adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and binding of lectins to the corneaCornea1990932662702115422

- AlizadehHNeelamSHurtMNiederkornJYRole of contact lens wear, bacterial flora, and mannose-induced pathogenic protease in the pathogenesis of amoebic keratitisInfect Immun20057321061106815664950

- PanjwaniNPathogenesis of acanthamoeba keratitisOcul Surf201082707920427010

- ClarkeDWNiederkornJYThe pathophysiology of Acanthamoeba keratitisTrends Parasitol200622417518016500148

- ClarkeDWAlizadehHNiederkornJYFailure of Acanthamoeba castellanii to produce intraocular infectionsInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20054672472247815980238

- LloydDEncystment in Acanthamoeba castellanii: a reviewExp Parastiol2014145SupplS20S27

- YangYFMathesonMDartJKCreeIAPersistence of acanthamoeba antigen following acanthamoeba keratitisBr J Ophthalmol200185327728011222330

- RobboyMWComstockTLKalsowCMContact lens-associated corneal infiltratesEye Contact Lens200329314615412861108

- SteinRMClinchTECohenEJGenvertGIArentsenJJLaibsonPRInfected vs sterile corneal infiltrates in contact lens wearersAm J Ophthalmol198810566326363377041

- KlotzSAPennCCNegveskyGJButrusSIFungal and parasitic infections of the eyeClin Microbiol Rev200013466268511023963

- ThomasPALeckAKMyattMCharacteristic clinical features as an aid to the diagnosis of suppurative keratitis caused by filamentous fungiBr J Ophthalmol200589121554155816299128

- HuFRHuangWJHuangSFClinicopathologic study of satellite lesions in nontuberculous mycobacterial keratitisJpn J Ophthalmol19984221151189587843

- WilhelmusKRJonesDBCurvularia keratitisTrans Am Ophthalmol Soc200199111130 discussion 130–13211797300

- DartJKSawVPKilvingtonSAcanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis and treatment update 2009Am J Ophthalmol20091484487499.e48219660733

- QianYMeislerDMLangstonRHJengBHClinical experience with Acanthamoeba keratitis at the Cole eye institute, 1999–2008Cornea20102991016102120539213

- RossJRoySLMathersWDClinical characteristics of Acanthamoeba keratitis infections in 28 states, 2008 to 2011Cornea201433216116824322804

- HauSCDartJKVesaluomaMDiagnostic accuracy of microbial keratitis with in vivo scanning laser confocal microscopyBr J Ophthalmol201094898298720538659

- TuEYJoslinCESugarJBootonGCShoffMEFuerstPAThe relative value of confocal microscopy and superficial corneal scrapings in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitisCornea200827776477218650660

- ConstantinouMDaniellMSnibsonGRVuHTTaylorHRClinical efficacy of moxifloxacin in the treatment of bacterial keratitis: a randomized clinical trialOphthalmology200711491622162917822972

- GangopadhyayNDaniellMWeihLTaylorHRFluoroquinolone and fortified antibiotics for treating bacterial corneal ulcersBr J Ophthalmol200084437838410729294

- KhokharSSindhuNMirdhaBRComparison of topical 0.3% ofloxacin to fortified tobramycin-cefazolin in the therapy of bacterial keratitisInfection200028314915210879638

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea/External Disease PanelPreferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. Bacterial KeratitisSan Francisco, CAAmerican Academy of Ophthalmology2013 Available from: http://www.aao.org/pppAccessed November 18, 2015

- NiNNamEMHammersmithKMSeasonal, geographic, and antimicrobial resistance patterns in microbial keratitis: 4-year experience in eastern PennsylvaniaCornea201534329630225603231

- AsbellPASahmDFShawMDraghiDCBrownNPIncreasing prevalence of methicillin resistance in serious ocular infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus in the United States: 2000 to 2005J Cat Refract Surg2008345814818

- SandersMEMooreQC3rdNorcrossEWComparison of besifloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxifloxacin against strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with different quinolone susceptibility patterns in a rabbit model of keratitisCornea2011301839020847656

- SanfilippoCMMorrisseyIJanesRMorrisTWSurveillance of the activity of aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones against ophthalmic pathogens from Europe in 2010–2011Curr Eye Res201519

- ElsahnAFYildizEHJungkindDLIn vitro susceptibility patterns of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus corneal isolates to antibioticsCornea201029101131113520595899

- RattanatamTHengWJRapuanoCJLaibsonPRCohenEJTrends in contact lens-related corneal ulcersCornea200120329029411322418

- SrinivasanMMascarenhasJRajaramanRCorticosteroids for bacterial keratitis: the Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial (SCUT)Arch Ophthalmol2012130214315021987582

- LohRSChanCMTiSELimLChanKSTanDTEmerging prevalence of microsporidial keratitis in Singapore: epidemiology, clinical features, and managementOphthalmology2009116122348235319815287

- OuJIAcharyaNREpidemiology and treatment of fungal corneal ulcersInt Ophthalmol Clin200747371617667272

- PrajnaNVKrishnanTMascarenhasJThe mycotic ulcer treatment trial: a randomized trial comparing natamycin vs voriconazoleJAMA Ophthalmol2013131442242923710492

- ChinJYoungALHuiMJhanjiVAcanthamoeba keratitis: 10-year study at a tertiary eye care center in Hong KongCont Lens Anterior Eye20153829910325496910

- OldenburgCEAcharyaNRTuEYPractice patterns and opinions in the treatment of acanthamoeba keratitisCornea201130121363136821993459

- TuEYJoslinCEShoffMESuccessful treatment of chronic stromal acanthamoeba keratitis with oral voriconazole monotherapyCornea20102991066106820539217

- KitzmannASGoinsKMSutphinJEWagonerMDKeratoplasty for treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitisOphthalmology2009116586486919410943

- IseliHPThielMAHafeziFKampmeierJSeilerTUltraviolet A/riboflavin corneal cross-linking for infectious keratitis associated with corneal meltsCornea200827559059418520510

- MartinsSACombsJCNogueraGAntimicrobial efficacy of riboflavin/UVA combination (365 nm) in vitro for bacterial and fungal isolates: a potential new treatment for infectious keratitisInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci20084983402340818408193

- MorenHMalmsjoMMortensenJOhrstromARiboflavin and ultraviolet a collagen crosslinking of the cornea for the treatment of keratitisCornea201029110210419730094

- BarequetISHabot-WilnerZKellerNEffect of amniotic membrane transplantation on the healing of bacterial keratitisInvest Ophthalmol Vis Sci200849116316718172088

- ParkJLeeKMZhouHCommunity practice patterns for bacterial corneal ulcer evaluation and treatmentEye Contact Lens2015411121825536529

- YildizEHAirianiSHammersmithKMTrends in contact lens-related corneal ulcers at a tertiary referral centerCornea201231101097110222902490

- GraffiSPeretzAJabalyHNaftaliMAcanthamoeba keratitisIsr Med Assoc J201315418218523781754

- OsterbladMJarvinenHLonnqvistKEvaluation of a new cellulose sponge-tipped swab for microbiological sampling: a laboratory and clinical investigationJ Clin Microbiol20034151894190012734223

- Pakzad-VaeziKLevasseurSDSchendelSThe corneal ulcer one-touch study: a simplified microbiological specimen collection methodAm J Ophthalmol201515913743.e3125244977

- Van HornKGAudetteCDSebeckDTuckerKAComparison of the Copan ESwab system with two Amies agar swab transport systems for maintenance of microorganism viabilityJ Clin Microbiol20084651655165818353935

- GoldschmidtPRostaneHSaint-JeanCEffects of topical anaesthetics and fluorescein on the real-time PCR used for the diagnosis of Herpes viruses and Acanthamoeba keratitisBr J Ophthalmol200690111354135616899529

- DasSSheoreyHTaylorHRVajpayeeRBAssociation between cultures of contact lens and corneal scraping in contact lens related microbial keratitisArch Ophthalmol200712591182118517846356

- KondaNMotukupallySRGargPSharmaSAliMHWillcoxMDMicrobial analyses of contact lens-associated microbial keratitisOptom Vis Sci2014911475324212183

- McLaughlin-BorlaceLStapletonFMathesonMDartJKBacterial biofilm on contact lenses and lens storage cases in wearers with microbial keratitisJ Appl Microbiol19988458278389674137

- MartinsENFarahMEAlvarengaLSYuMCHoflin-LimaALInfectious keratitis: correlation between corneal and contact lens culturesCLAO J200228314614812144234

- Mah-SadorraJHYavuzSGNajjarDMLaibsonPRRapuanoCJCohenEJTrends in contact lens-related corneal ulcersCornea2005241515815604867

- MusaFTailorRGaoAHutleyERauzSScottRAContact lens-related microbial keratitis in deployed British military personnelBr J Ophthalmol201094898899320576772

- KeayLJGowerEWIovienoAClinical and microbiological characteristics of fungal keratitis in the United States, 2001–2007: a multicenter studyOphthalmology2011118592092621295857

- MathersWDNelsonSELaneJLWilsonMEAllenRCFolbergRConfirmation of confocal microscopy diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis using polymerase chain reaction analysisArch Ophthalmol2000118217818310676782

- CDCAcanthamoeba keratitis associated with contact lenses – United StatesMMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep198635254054083088418

- ButlerTKMalesJJRobinsonLPSix-year review of Acanthamoeba keratitis in New South Wales, Australia: 1997–2002Clin Exp Ophthalmol2005331414615670077

- RadfordCFLehmannOJDartJKAcanthamoeba keratitis: multi-centre survey in England 1992–1996. National Acanthamoeba Keratitis Study GroupBr J Ophthalmol19988212138713929930269

- IyerSATuliSSWagonerRCFungal keratitis: emerging trends and treatment outcomesEye Contact Lens200632626727117099386

- PrajnaNVSrinivasanMLalithaPDifferences in clinical outcomes in keratitis due to fungus and bacteriaJAMA Ophthalmol201313181088108923929517

- MiedziakAIMillerMRRapuanoCJLaibsonPRCohenEJRisk factors in microbial keratitis leading to penetrating keratoplastyOphthalmology1999106611661170 discussion 117110366087

- TuEYAcanthamoeba keratitis: a new normalAm J Ophthalmol2014158341741925012982

- YoderJSVeraniJHeidmanNAcanthamoeba keratitis: the persistence of cases following a multistate outbreakOphthalmic Epidemiol201219422122522775278