Abstract

Background

Endoscopic thyroidectomy allows surgeons to remove a thyroid tumor from a remote site, while providing excellent results from a cosmetic viewpoint. Endoscopic thyroidectomy via the breast approach is a recent technique that requires a learning curve. Research on the learning curve for endoscopic thyroidectomy could be a method for investigating the surgical outcome.

Methods

This retrospective study investigated 100 consecutive patients who underwent endoscopic thyroidectomy performed by a single endoscopist over a period of 5 years. From January 2007 to December 2011, 100 of 355 patients scheduled for endoscopic thyroidectomy selected the breast approach. We divided the patients into four groups. Each group consisted of 25 patients: group A (cases 1–25), group B (cases 26–50), group C (cases 51–75), and group D (cases 76–100).

Results

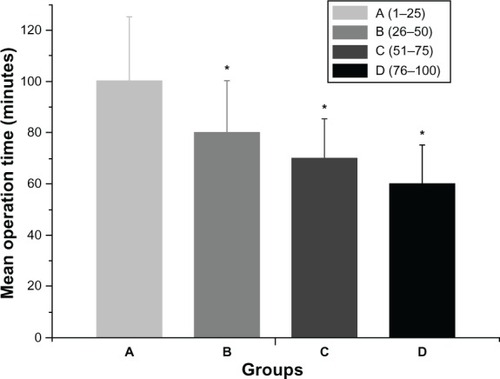

The operative times for groups A, B, C, and D were 100.52 ± 25.13, 80.34 ± 20.22, 72.42 ± 15.33, and 63.35 ± 15.11 minutes, respectively (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

After 25 cases, we observed that endoscopic thyroidectomy via the breast approach enables a shorter mean operative time and a reduced complication rate.

Introduction

Thyroid is one of the largest endocrine glands, and is found in the neck, inferior to the thyroid cartilage. Thyroid disorders include hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and thyroid nodules. Nodules are commonly benign neoplasms, but may be cancerous. All these disorders can lead to goiter, a swelling of the thyroid gland that can cause a swelling in the neck. Some thyroid disorders need surgical treatment, including a thyroid nodule with a diameter more than 1 cm and fine needle aspiration biopsy for a suspected neoplasm,Citation1,Citation2 a thyroid nodule with a diameter less than 1 cm and fine needle aspiration indeterminate more than once,Citation1,Citation2 a thyroid nodule and fine needle aspiration positive for malignancy,Citation2–Citation4 multiple thyroid nodules having the same malignant possibility as one positive nodule,Citation5,Citation6 differentiated thyroid cancer,Citation7 medullary thyroid cancer,Citation8,Citation9 prophylaxis in cases with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome,Citation10 anaplastic carcinoma,Citation11 and thyrotoxic disease.Citation12

Endoscopic thyroidectomy and robotic thyroidectomy (the da Vinci surgical system) allow surgeons to remove a thyroid tumor from a remote site, while providing excellent results from a cosmetic viewpoint.Citation13–Citation15 The goals of endoscopic thyroidectomy are to limit external scarring and improve cosmesis, to reduce postoperative pain, to enhance postoperative recovery, and to achieve these ends without compromising treatment efficacy. Endoscopic thyroidectomy was first described by Hüscher et al in 1997.Citation16 Most of the earlier endoscopic approaches to the thyroid gland employed small cervical incisions in the midline or laterally. To avoid a visible scar on the neck, noncervical approaches to the thyroid gland have been used. The most commonly used noncervical approaches are axillary,Citation17 via the breast,Citation18 lateral,Citation19 transoral,Citation20 and also certain hybrid approaches,Citation21 such as the bilateral axillary-breast approach, the bilateral axillo-breast approach, the unilateral axillo-breast approach, and the postauricular and axillary approach. Among these, the breast approach has emerged as a clear favorite, as evidenced by its exponential growth in the mainland of China.Citation13,Citation22,Citation23

Although evidence-based data reporting short-term and long-term outcome data after endoscopic resection for different thyroid diseases have shown clear advantages in comparison with traditional procedures, endoscopic thyroidectomy has not been widely accepted. One of the reasons for this initial refusal is the technical difficulty of endoscopic resection requiring adequate training both in open and endoscopic procedures before gland resection can be performed safely. Study of the learning curve for endoscopic thyroidectomy could be a method for investigating the surgical outcome. The present study sought to evaluate the learning curve for duration of endoscopic thyroidectomy performed by a surgeon with wide experience in open thyroidectomy.

Materials and methods

Patients

From January 2007 to December 2011, 100 of 355 patients selected endoscopic thyroidectomy via the breast approach. All were concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the neck and chose this procedure as their preferred surgical treatment. The characteristics of the patients are shown in . This was a retrospective analysis of the surgical outcomes for the groups performed by the same group of surgeons. All operations were performed by a single surgeon (FC) assisted by two of the other authors (BX and BC). All cases were identifed from a thyroid surgery patient database, prospectively maintained by one of the authors (BX). Informed consent was obtained from each patient before surgery in all cases. The study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital.

Table 1 Clinical patient data

All patients were evaluated preoperatively using ultrasonography, computed tomographic scan, and fine needle aspiration cytology. All patients underwent direct laryngoscopy preoperatively to assess vocal cord motility. The inclusion criteria used for endoscopic thyroidectomy are shown in . The main surgical outcome measures were operative time (interval from skin incision to skin closure), postoperative hospital stay, identification of recurrent laryngeal nerve, identification of parathyroid glands, conversion to an open surgical pro cedure, postoperative calcemia, postoperative vocal alteration, postoperative complications, and pathological characteristics. The following complications were analyzed: transient or permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, transient or permanent hypocalcemia, redo surgery for hemorrhage, and postoperative pain. Patients were tested for hypocalcemia preoperatively and on postoperative days 1 and 30. All patients with a postoperative calcium level below the lower limit of the normal range (8.2–10.6 mg/dL) were considered to have hypocalcemia. In this study, hypocalcemia and recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy were defined as permanent when there was no evidence of recovery within 30 days after surgery. Patients in both groups were followed up at days 7 and 30 by office visit or phone call for hoarseness of voice, difficulty in swallowing, hypesthesia, and paresthesia. The data were analyzed for statistical significance using the Student’s t-test and Chi-square test. P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Table 2 inclusion criteria

Surgical procedure

The surgical procedure for endoscopic thyroidectomy via the breast approach has been described elsewhere.Citation13 Briefly, endoscopic thyroidectomy was performed via the breast approach under general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation. Patients were placed in the supine position with extension of the neck. A 15 mm incision in the presternal region (for placement of the Hanson trocar) and two 5 mm incisions in the superior areas of both mammary areolas were performed. A dilute epinephrine saline solution (1:200,000) was injected into the subcutaneous space in the breast and subplatysmal space in the neck to ease flap dissection and to prevent bleeding. Using a standard curve access vascular tunneler (WL Gore and Associates Inc, Flagstaff, AZ), the working space was extended. After blunt dissection of the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior chest wall through this incision, a 15 mm trocar was inserted. The working area was maintained with low pressure CO2 insufflation at a pressure of 10 mmHg, and a 30-degree 5 mm flexible endoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted through the trocar. The working space was made wide to the level of the thyroid cartilage cranially and to the medial edge of each of the sternocleidomastoid muscles laterally with visual guidance by the endoscope. After the working space was set up, two 5 mm incisions were made and two 5 mm trocars were inserted. Thyroid vessel management and thyroidectomy were performed endoscopically using a 5 mm ultrasonic coagulation device (Harmonic scalpel, Ethicon Endosurgery, Somerville, NJ). After dissecting the strap muscles in the midline endoscopically, the isthmus was divided. Traction over the ipsilateral strap muscles was then oriented laterally to reveal the right lobe. After cutting the inferior thyroid arteries and veins and the middle thyroid vein, the lobe was retracted downwards to expose the superior thyroid arteries, which were then dissected using the Harmonic scalpel. Next, the lobe was gently lifted up and the whole cervical course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve up to the inferior constrictor muscle of the pharynx was traced and protected, as well as both the inferior and superior parathyroid glands. Magnification of the endoscope allowed easy identification of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and parathyroid glands.

Lastly, the lobe was excised from the inferior pole up towards the superior pole. The left lobe could be excised in the same manner as for the right lobe. The resected specimen was inserted into a retrieval bag and retrieved through the 15 mm port. A frozen section of the resected specimen was examined intraoperatively for pathological confrmation. Homeostasis was checked at the end of dissection. After cleaning the cavity with physiological saline solution, the strap muscles were sutured. An aspiration drainage tube was left in situ in the central compartment, and was removed 48 hours after surgery.

Results

All of the 100 cases met the inclusion criteria for endoscopic thyroidectomy. The mean age of the patients was 35.52 ± 11.69 (range 17–55) years. The male to female gender ratio was 5:95. All patients were treated by unilateral lobectomy. Patient characteristics are presented in .

The mean duration of surgery for each group was 100.52 ± 25.13, 80.34 ± 20.22, 72.42 ± 15.33, and 63.35 ± 15.11 minutes, respectively. Comparison of neighboring groups showed differences in operative time between groups A and B (P < 0.05), groups B and C (P < 0.05), and groups C and D (P < 0.05, ). None of the patients were converted to an open surgical procedure. Postoperative complications are shown in . Transient hypocalcemia was found in one patient. No permanent hypocalcemia occurred. Transient recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy occurred in three patients. No permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy occurred. Postoperative pain was reported by five patients at 24 hours following surgery.

Table 3 Postoperative complications

Seventy-seven patients had nodular goiter on histopathological examination (). Fifteen patients had follicular adenoma, and seven had Hurthle cell adenoma. Only one patient had cystic lesions.

Table 4 Histopathological findings

Discussion

A learning curve for an operation refers to the number of cases a surgical firm needs to perform before the operative time and complication rate become reproducibly minimized.Citation24 However, a more signifying definition is needed, with renewal of estimation criteria for different surgical styles. The learning curve seems to be a more scientific estimation system for the perioperative period, which should include the appropriateness of the chosen surgical indications, rationality of the procedural steps, quality of manipulation, recovery of the patient, and postoperative quality of life.Citation25,Citation26 Based on all these considerations, the clinical directive effect of the learning curve should be complete.

Since the first case in January 2007, 355 patients have undergone endoscopic thyroidectomy at our study center during the past 5 years. All these procedures were performed by a single surgeon (FC). We collected the first 100 cases and divided them into four consecutive groups chronologically, each group comprising 25 cases.

Endoscopic thyroidectomy requires a great deal of experience in thyroid surgery, correct selection of patients, and proper performance and management of the endoscopic procedure. Perfect anatomical knowledge of the neck and solid surgical experience in total thyroidectomy are fundamental elements of the endoscopic surgical approach. All new procedures have a learning curve. Therefore, in our experience, the first problem was the operative time. We observed a shortening of the operative time after treatment of the first 25 cases.

As described in the surgical procedure, magnification of the endoscope allowed easy identification of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Transient/permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy is one of the common complications of endoscopic thyroidectomy. With the lateral view of the thyroid gland, we easily identifed and preserved the recurrent laryngeal nerve while performing the endoscopic thyroidectomy. However, some major improvements and safer technologies, such as intraoperative neuromonitoring to prevent paralysis of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, have been proposed and would be considered for application in thyroid surgery in subsequent years.Citation27

In conclusion, we consider that endoscopic thyroidectomy should be performed when the inclusion criteria are met. However, the surgeon must be expert in open thyroid surgery to be able to undertake this surgical approach.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Healthy Science and Technology Projects (2011KYB137), Science Research Fund of Taizhou (A102KY09), Science Research Fund of Shaoxing (2011D10013), and Science Research Fund of Zhuji (2011CC7874).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KelmanASRathanALeibowitzJBursteinDEHaberRSThyroid cytology and the risk of malignancy in thyroid nodules: importance of nuclear atypia in indeterminate specimensThyroid200111327127711327619

- TuttleRMLemarHBurchHBClinical features associated with an increased risk of thyroid malignancy in patients with follicular neoplasia by fine-needle aspirationThyroid1998853773839623727

- GoldsteinRENettervilleJLBurkeyBJohnsonJEImplications of follicular neoplasms, atypia, and lesions suspicious for malignancy diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodulesAnn Surg2002235565666211981211

- SchlinkertRTvan HeerdenJAGoellnerJRFactors that predict malignant thyroid lesions when fine-needle aspiration is “suspicious for follicular neoplasm”Mayo Clin Proc199772109139169379692

- MarquseeEBensonCBFratesMCUsefulness of ultrasonography in the management of nodular thyroid diseaseAnn Intern Med2000133969670011074902

- SegevDLClarkD PZeigerMAUmbrichtCBeyond the suspicious thyroid fine needle aspirate. A reviewActa Cytol200347570972214526667

- CooperDSDohertyGMHaugenBRAmerican Thyroid Association Guidelines Taskforce. Management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancerThyroid200616210914216420177

- ShermanSIThyroid carcinomaLancet2003361935650151112583960

- GharibHGoellnerJRJohnsonDAFine-needle aspiration cytology of the thyroid. A 12-year experience with 11,000 biopsiesClin Lab Med19931336997098222583

- SkinnerMAMoleyJADilleyWGOwzarKDebenedettiMKWellsSAJrProphylactic thyroidectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2AN Engl J Med2005353111105111316162881

- NelCJvan HeerdenJAGoellnerJRAnaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid: a clinicopathologic study of 82 casesMayo Clin Proc198560151583965822

- GoughIRWilkinsonDTotal thyroidectomy for management of thyroid diseaseWorld J Surg200024896296510865041

- CaoFLXieBJCuiBBXuDEndoscopic vs conventional thyroidectomy for the treatment of benign thyroid tumors: a retrospective study of a 4-year experienceExp Ther Med20112466166622977557

- BrunaudLGermainAZarnegarRKleinMAyavABreslerLRobotic thyroid surgery using a gasless transaxillary approach: cosmetic improvement or improved quality of surgical dissection?J Visc Surg20101476e399e40221095176

- LeeJChungWYCurrent status of robotic thyroidectomy and neck dissection using a gasless transaxillary approachCurr Opin Oncol201224171522080943

- HüscherCSChiodiniSNapolitanoCRecherAEndoscopic right thyroid lobectomySurg Endosc19971188779266657

- DuncanTDRashidQSpeightsFEjehIEndoscopic transaxillary approach to the thyroid gland: our early experienceSurg Endosc200721122166217117479328

- ChoYUParkIJChoiKHGasless endoscopic thyroidectomy via an anterior chest wall approach using a flap-lifting systemYonsei Med J200748348048717594157

- PalazzoF FSebagFHenryJFEndocrine surgical technique: endoscopic thyroidectomy via the lateral approachSurg Endosc200620233934216362471

- WitzelKvon RahdenBHKaminskiCSteinHJTransoral access for endoscopic thyroid resectionSurg Endosc20082281871187518163167

- LeeKEKimHYParkWSPostauricular and axillary approach endoscopic neck surgery: a new techniqueWorld J Surg200933476777219198933

- NgWTEndoscopic thyroidectomy in ChinaSurg Endosc20092371675167719343423

- ZhangWJiangDZLiuSCurrent status of endoscopic thyroid surgery in ChinaSurg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech2011212677121471794

- LeongSCahillRAMehiganBJStephensRBConsiderations on the learning curve for laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a view from the bottomInt J Colorectal Dis20072291109111517404746

- AhlbergGKruunaOLeijonmarckCEIs the learning curve for laparoscopic fundoplication determined by the teacher or the pupil?Am J Surg2005189218418915720987

- GillJBoothMIStratfordJDehnTCThe extended learning curve for laparoscopic fundoplication: a cohort analysis of 400 consecutive casesJ Gastrointest Surg200711448749217436134

- WitzelKBenhidjebTMonitoring of the recurrent laryngeal nerve in totally endoscopic thyroid surgeryEur Surg Res2009432727619478487