Abstract

Background

To evaluate the benefit of second-line chemotherapy with platinum-based treatment in patients with recurrent small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Patients and methods

A total of 535 patients continued with follow-up or best supportive care if needed, and 229 patients who progressed after the completion of first-line chemotherapy were treated with second-line chemotherapy at the time of progression. In total, 103/229 patients received paclitaxel 190 mg/m2 and carboplatin 5.5 area under the curve while 126/229 patients received etoposide 200 mg/m2 and carboplatin 5.5 area under the curve every 28 days.

Results

Patients administered second-line chemotherapy lived significantly longer, with a median survival of 422 days compared to 228 days in patients with best supportive care alone (P<0.001). Patients who received paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy lived for an average of 462 days (95% confidence interval: 409–514), versus 405 days in the etoposide group (95% confidence interval: 371–438), which was not statistically significant (P=0.086). The overall response rate was 8% for the paclitaxel group and 6% for the etoposide group. Patients with progression of the disease in more than 3 months had significantly better survival compared with those that progressed in less than 3 months (P<0.001).

Conclusion

Continuation with carboplatin/paclitaxel or carboplatin/etoposide as second-line chemotherapy has no significant survival impact, and it did not improve response rates.

Keywords:

Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide, and despite recent advances in management strategies, improvements in survival have been small. Prognosis in SCLC remains poor, with 5-year survival rates for limited disease (LD) and extensive disease (ED) of around 10% and 2%, respectively.Citation1,Citation2 This reflects the fact that, although SCLC is initially a chemosensitive disease (with response rates [RRs] to first-line treatment on the order of 70%–90% in LD and 50%–60% in ED),Citation3 relapse is a major problem. The majority of patients relapse (~80% of LD patients and almost all ED patients), and this most commonly occurs within the first year after initial treatment.Citation4 If they relapse within 90 days of treatment, they are called chemotherapy-resistant, as opposed to chemotherapy-sensitive patients, who relapse after this time. Patients who are chemotherapy-resistant tend to have poor overall survival (OS), with an RR to additional chemotherapy of around 10% or less; however, for chemosensitive patients, this rate can be up to 25%.Citation5

To date, there are only a few systematic data available regarding the efficacy and toxicity of subsequent chemotherapy. Topotecan is currently the only drug licensed in Europe and in the US for the treatment of relapsed SCLC when retreatment with the first-line agent is not appropriate, while another drug, amrubicin, is approved for use only in Japan.Citation6,Citation7 Various alternative drug combinations have been assessed in Phase II trials. Taxanes have very good RRs in many cancers, even when used as second-line or third-line treatment. More specifically, paclitaxel is a promising single agent in chemorefractory SCLC patients, but the drug has had a high incidence of febrile neutropenia, as evident in Phase II studies.Citation8–Citation10 Moreover, the combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel showed an RR of 73.5%, with two patients achieving complete response (CR) in a Phase II study involving 35 SCLC patients who were refractory to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide therapy.Citation11

The aim of this retrospective study is, therefore, to present the results of a large, unselected, and contemporary patient population with LD and ED SCLC treated at our institution over a 10-year period. Specifically, the objective is to examine the benefit of platinum-based chemotherapy in the second-line treatment setting following induction chemotherapy with platinum analogs.

Patients and methods

For each patient with SCLC, who was found by a search in our patient data system between January 2000 and January 2010, every single electronic report was reviewed. Every patient underwent a diagnostic workup including a computed tomography (CT) of the thorax and upper abdomen, CT or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, bronchoscopy, and a bone scan. Restaging was done by repeating the same examinations. We collected data on age, disease stage, date of initial diagnosis, last observation and survival, performance status (PS), metastatic sites, type and number of courses of first-line and subsequent lines of chemotherapy, key hematological and nonhematological toxicities, result/benefit of first-line chemotherapy (CR, partial response, stable disease, and progressive disease), and result/benefit of second and subsequent lines of chemotherapy. Time to tumor progression (TTP) was assessed after each line of chemotherapy. Both the site of relapse and PS before the start of the second-line therapy were analyzed. Overall, the patients had a good PS (30% had 0 PS; 70% had 1 PS). Data on prophylactic and palliative radiotherapy were additionally retrieved. We used the US Veterans Administration Lung Study Group criteria to define LD and ED SCLC.Citation5 Patients with progression of the disease within up to 3 months were given a new line of chemotherapy, while patients with a time to progression of 3 months or longer were given reinduction therapy. First-line therapy consisted of either carboplatin (area under the curve 5.5 intravenously [IV] on day 1) and etoposide (100 mg/m2 IV on days 1–3), or carboplatin (area under the curve 5.5 IV day 1) and paclitaxel was added at a dose of 190 mg/m2 IV on day 1. All regimens were given every 4 weeks. In the second-line setting, we employed the same regimens, depending on each patient’s response to the initial treatment.

Results

From January 2000 to January 2010, 764 patients with newly diagnosed SCLC were identified. In all, 36% of the patients had LD and 64% had ED at the time of diagnosis. The median OS for all patients was 265 days. Patients’ characteristics are shown in .

Table 1 Patients’ characteristics

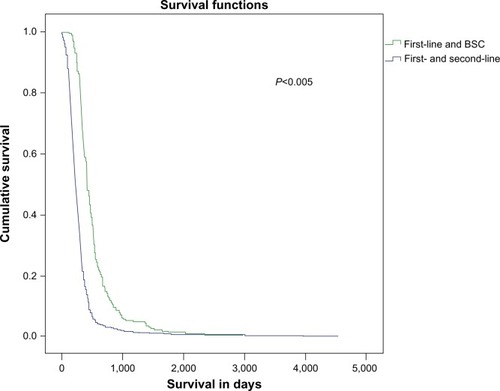

Among 764 patients, 229 (30%) received second-line chemotherapy and 535 continued with best supportive care (BSC) treatment, and there was a great survival benefit for the second-line group compared with the BSC group (422 days versus 228 days; P<0.001) (). The factors that affected our decision to not submit the remaining 535 patients (70%) to second-line chemotherapy are presented in . presents the OS and TTP in days among patients that were divided according to the stage of their disease (LD or ED).

Figure 1 Survival in days among patients on first-line and BSC, and first-line and second-line chemotherapy.

Table 2 Factors that affected the decision for second-line chemotherapy for the 535 patients (70%)

Table 3 OS and TTP in LD and ED patients

If we measure survival for patients who received second-line therapy from the first time to progression according to their second-line regimen response (OR [overall response], SD [stable disease], and PD [progressive disease]), we concluded that better responses were associated with longer survival among patients (253 days for OR patients; 194 days for SD; and 130 for PD; P=0.001, log rank test).

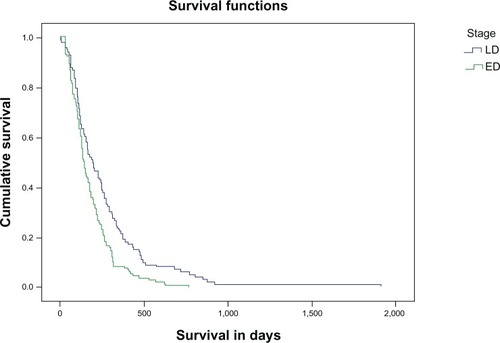

OS from TTP is not affected by patients’ first-line regimen response (OR, SD, and PD; P>0.05). Survival from TTP according to the LD or ED stage is statistically significant for LD patients (P=0.001) and is shown in .

Figure 2 Survival in days according to the stage of the disease, LD or ED.

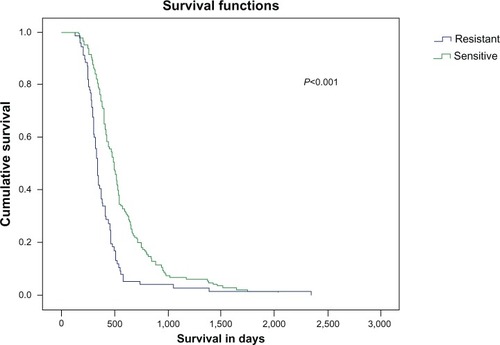

Moreover, patients with sensitive disease (progression within more than 3 months after the completion of six cycles of first-line chemotherapy), seem to live significantly longer (P=0.001) compared to patients who are resistant to chemotherapy and experienced progression of their disease in less than 3 months after the completion of six cycles of first-line chemotherapy. The median OS for sensitive and resistant patients in LD and ED from TTP is shown in .

Table 4 Median OS in days for sensitive and resistant patients in LD and ED (from TTP) after the administration of second-line chemotherapy

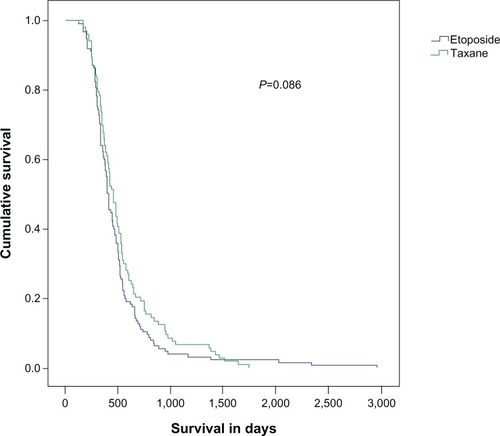

Among 229 patients with second-line treatment, 103 received paclitaxel and carboplatin, and 126 received etoposide and carboplatin (ECb) as second-line therapy. Patients who received paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy lived for an average of 462 days (95% confidence interval: 409–514) versus 405 days in the etoposide group (95% confidence interval: 371–438), which was not statistically significant (P=0.086) (). The overall RR (ORR) was 8% for paclitaxel group and 6% for the etoposide group. Among 103 patients who received paclitaxel–carboplatin as second-line chemotherapy, 85 patients received the same agents as first-line treatment with an initial RR of 47%.

Figure 3 Survival in the etoposide–carboplatin and paclitaxel–carboplatin groups as second-line chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer patients.

Patients who experienced progression of the disease within 3 months after the completion of the first-line chemotherapy received the same regimens as in second-line chemotherapy: 20 patients received ECb, and 36 patients received paclitaxel and carboplatin at the initial doses. Statistical analyses did not show differences in survival rates (522 days and 647 days, respectively; P=0.071) and TTP (121 days and 128 days, respectively; P>0.05).

Toxicity

Among grade 3–4 toxicity, the mostly commonly encountered grade 3–4 toxicities were neutropenia (12% in LD and 16% in ED) and anemia (9% in LD and 11% in ED). There were no treatment-related deaths. The most frequent nonhematological toxicity was fatigue, which occurred in 37% of patients. The second most common nonhematological toxicity was anorexia, occurring in 33% of patients. All other hematological and nonhematological toxicities were relatively infrequent and tolerable ().

Table 5 Grade 3–4 main hematological and nonhematological toxicities of second-line chemotherapy in LD and ED

Discussion

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network practice guidelines for the first-line treatment of SCLC named the etoposide– cisplatin (EC) regimen as the treatment of choice to be used concurrently with radiotherapy.Citation12,Citation23 The treatment of the LD-SCLC patients, who experienced significant tumor regression, was followed by prophylactic cranial irradiation. The EC combination is also frequently used in patients with ED-SCLC.

On the other hand, the RR of ECb combination is around 60% with a median survival of 8–9 months. In a small study, the ECb and EC combinations were compared, and the researchers reported the equivalence of the two treatments, although ECb was found to be less toxic.Citation13 A number of studies with paclitaxel as monotherapy or as part of combination regimens have been evaluated with inconsistent results in first- and second-line treatment.Citation14,Citation15

In our study, a statistically significant increase in OS was observed in patients receiving second-line chemotherapy when compared to those receiving only first-line chemotherapy followed by BSC (median OS: 14 months versus 7.6 months; P=0.001). The response to second-line treatment (median survival for OR patients: 8.4 months; SD patients: 6.4 months; and PD patients: 4.3 months; P=0.001), the extent of the disease (LD versus ED; P=0.001), and the sensitivity to first-line treatment (progression <3 months versus >3 months; P=0.029) of the patients who received second-line chemotherapy played a significant role in OS (). However, there was no statistical difference observed in the TTP and OS between patients treated with either the paclitaxel–carboplatin or ECb combinations as second-line treatment ().

Figure 4 Survival in days in patients resistant and sensitive to chemotherapy from the time of diagnosis.

The ORR in the second-line setting was very low (7% overall; for patients on paclitaxel–carboplatin treatment, it was 8%, and for ECb treatment, it was 6%) compared with ORR of 7%–73% observed in other previously reported studies.Citation16,Citation25,Citation26 On the other hand, the stability of the disease (46%) and the OS for LD (median OS: 260 days/8.6 months, for sensitive 297 days/9.9 months, resistant 155 days/5 months) and ED (median OS: 212 days/7 months, sensitive 267 days/8.9 months, resistant 146 days/4.9 months) were similar to those found in other investigational studies.Citation16,Citation25,Citation26 An explanation for these findings is that patients were treated in one pulmonary department where the criteria of OR were more strict; standard procedures involved taking at least a second look using bronchoscopy in patients with CR in CT imaging. Another possible explanation is that there were frequent reevaluations of patients using X-rays or CT scans.

Sundstrøm et al,Citation17 Kim et al,Citation18 and Agelaki et al,Citation19 reported that PS at the time of disease recurrence was a significant prognostic factor that also influenced the progression-free survival and OS. In our study, all of the patients had a good PS (30% had 0 PS; 70% had 1 PS); thus, the importance of the PS was not significant. However, in our analysis of the PS, the level of sensitivity in the first-line treatment and the extent of the disease at the time when the second-line treatment started should be considered as essential factors for the increase in OS.

Although our results are derived from a monoinstitutional retrospective analysis, this limitation provides homogeneity of the patients’ characteristics, their evaluation, and their management. The diagnosis and staging of the patients were performed with modern techniques. Patients on first-line and second-line chemotherapy treatments were treated with modern platinum-based combinations and with the same therapeutic philosophy, as far as time of radiotherapy and prophylactic cranial irradiation were concerned. Thus, we believe that this homogeneity led to safer results regarding the utility of the second-line chemotherapy in patients with SCLC who either relapsed or progressed during the first-line therapy. There was no significant statistical difference in sensitive patients treated with either reinduction of the first-line chemotherapy in the second-line, or when a different (platinum-based) combination was introduced. The combination of paclitaxel–carboplatin was equally effective when administered as a second-line therapy, indifferent to whether first-line treatment was paclitaxel–carboplatin or etoposide–carboplatin.

Another limitation of our study is the imbalance observed between the sexes (males to females). This may be due to the fact that smoking in Greece was adapted by females much later than in the rest of the European countries, and they also exhibit different lifestyles (nutrition, working conditions, living conditions).Citation20

After first-line chemotherapy, almost all SCLC patients that experienced disease relapse had a poor life expectancy (2–3 months) without second-line treatment.Citation21 As a result, the majority of these patients become candidates for second-line therapy. The evidence for the clinical benefit of second-line treatment in SCLC is limited. Unfortunately, large trials that compared BSC alone to second-line treatment (also called salvage chemotherapy) in SCLC are rare in the literature when compared to the findings available regarding non-SCLC.Citation21

In a meta-analysis that included two randomized clinical trials conducted with a total of 531 patients, second-line chemotherapy was compared with BSC or placebo in patients with ED-SCLC at relapse or progression.Citation22 Patients were randomized to receive either methotrexate–doxorubicin versus BSC or oral topotecan versus BSC. The ORR in the methotrexate– doxorubicin group was 22.3%, and 7% with topotecan. Toxicity was worse in the chemotherapy group. Topotecan has been shown to be superior as monotherapy when compared to supportive care alone (OS: 26 weeks versus 14 weeks; P=0.010).Citation22,Citation23 Another multicenter study randomized 211 sensitive SCLC patients who relapsed after front-line chemotherapy with etoposide–platinum, and these patients were randomized to receive a combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine (CAV) or topotecan. Similar antitumor activity was observed between CAV and topotecan in terms of RR, OS, and progression-free survival in the second-line setting.Citation24 In addition, oral topotecan appears to be equivalent to the IV form.Citation25 As a result, CAV and topotecan can be prescribed as second-line treatments for SCLC patients.

However, CAV showed modest activity with a low RR (≤10%–28%) in SCLC among progressed or relapsed patients initially treated with an EC combination.Citation26–Citation28 Taking into account that in North America and Europe the combination of EC or ECb is the cornerstone of SCLC treatment, it is unclear whether paclitaxel and carboplatin would have the same level of activity as a second-line treatment.

Conclusion

In our study, we explored the impact of paclitaxel– carboplatin as a second-line treatment following frontline treatment with a platinum-based regimen (either ECb or a paclitaxel– carboplatin combination) on the patients’ OS and RR in SCLC. At the end of the day, more prospective studies are needed to evaluate the role of second-line therapy regarding the choice of the most appropriate therapeutic combinations and the most appropriate prognostic and predictive factors (for example, sensitivity, PS, initial response to chemotherapy, extent of the disease, biological markers, age of the patients, and so on).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NavadaSLaiPSchwartzAGKalemkerianGPTemporal trends in small cell lung cancer: analysis of the national Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End-Results (SEER) databaseJ Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts)200624Suppl 18 Abstract 7082

- ZarogoulidisKLatsiosDPorpodisKZarogoulidisPDarwicheKAntoniouNHohenforst-SchmidtWEleftheriadouEBoutsikouEKontakiotisTNew dilemmas in small-cell lung cancer TNM clinical stagingOnco Targets Ther2013653954723700372

- ChengSEvansWKStys-NormanDShepherdFALung Cancer Disease Site Group of Cancer Care Ontario’s Program in Evidence-based CareChemotherapy for relapsed small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and practice guidelineJ Thorac Oncol20072434835417409809

- HurwitzJLMcCoyFScullinPFennellDANew advances in the second-line treatment of small cell lung cancerOncologist2009141098699419819917

- PostmusPEBerendsenHHvan ZandwijkNSplinterTABurghoutsJTBakkerWRetreatment with the induction regimen in small cell lung cancer relapsing after an initial response to short term chemotherapyEur J Cancer Clin Oncol1987239140914112824211

- KairaKSunagaNTomizawaYA phase II study of amrubicin, a synthetic 9-aminoanthracycline, in patients with previously treated lung cancerLung Cancer20106919910419853960

- JoosGSchallierDPinsonPSterckxMVan MeerbeeckJPPaclitaxel (PTX) as second line treatment in patients (pts) with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) refractory to carboplatin – etoposide: a multicenter phase II studyJ Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts)200422Suppl 14 Abstract 7211

- SmitEFFokkemaEBiesmaBGroenHJSnoekWPostmusPEA phase II study of paclitaxel in heavily pretreated patients with small-cell lung cancerBr J Cancer19987723473519461009

- HongJJungMKimYJPhase II study of combined belotecan and cisplatin as first-line chemotherapy in patients with extensive disease of small cell lung cancerCancer Chemother Pharmacol201269121522021691745

- ZarogoulidisKZiogasEBoutsikouEImmunomodifiers in combination with conventional chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer: a phase II, randomized studyDrug Des Devel Ther20137611617

- GroenHJFokkemaEBiesmaBPaclitaxel and carboplatin in the treatment of small-cell lung cancer patients resistant to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide: a non-cross-resistant scheduleJ Clin Oncol199917392793210071286

- MurrayNTurrisiAT3rdA review of first-line treatment for small-cell lung cancerJ Thorac Oncol20061327027817409868

- SkarlosDVSamantasEKosmidisPRandomized comparison of etoposide-cisplatin vs etoposide-carboplatin and irradiation in small-cell lung cancer. A Hellenic Co-operative Oncology Group studyAnn Oncol1994576016077993835

- NairBSBhanderiVJafriSHCurrent and emerging pharmacotherapies for the treatment of relapsed small cell lung cancerClin Med Insights Oncol2011522323421836818

- PopatSO’BrienMChemotherapy strategies in the treatment of small cell lung cancerAnticancer Drugs200516436137215746572

- KallianosARaptiAZarogoulidisPTherapeutic procedure in small cell lung cancerJ Thorac Dis20135S4S420S42424102016

- SundstrømSBremnesRMKaasaSAasebøUAamdalSNorwegian Lung Cancer Study GroupSecond-line chemotherapy in recurrent small cell lung cancer. Results from a crossover schedule after primary treatment with cisplatin and etoposide (EP-regimen) or cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and vincristin (CEV-regimen)Lung Cancer200548225126115829326

- KimYHGotoKYo hKPerformance status and sensitivity to first-line chemotherapy are significant prognostic factors in patients with recurrent small cell lung cancer receiving second-line chemotherapyCancer200811392518252318780323

- AgelakiSHatzidakiDKotsakisANon-platinum-based first-line followed by platinum-based second-line chemotherapy or the reverse sequence in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis by the lung cancer group of the Hellenic Oncology Research GroupOncology2010783–422923620523083

- FarsalinosKERomagnaGTsiaprasDKyrzopoulosSVoudrisVEvaluating nicotine levels selection and patterns of electronic cigarette use in a group of “vapers” who had achieved complete substitution of smokingSubst Abuse2013713914624049448

- PlanchardDLe PéchouxCSmall cell lung cancer: new clinical recommendations and current status of biomarker assessmentEur J Cancer201147Suppl 3S272S28321943984

- SpiroSGSouhamiRLGeddesDMDuration of chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer: a Cancer Research Campaign trialBr J Cancer19895945785832540788

- RossiAMartelliODi MaioMTreatment of patients with small-cell lung cancer: from meta-analyses to clinical practiceCancer Treat Rev201339549850623084098

- von PawelJSchillerJHShepherdFATopotecan versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine for the treatment of recurrent small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol199917265866710080612

- EckardtJRvon PawelJPujolJLPhase III study of oral compared with intravenous topotecan as second-line therapy in small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200725152086209217513814

- FukuokaMFuruseKSaijoNRandomized trial of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine versus cisplatin and etoposide versus alternation of these regimens in small-cell lung cancerJ Natl Cancer Inst199183128558611648142

- ShepherdFAEvansWKMacCormickRFeldRYa uJCCyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine in etoposide- and cisplatin-resistant small cell lung cancerCancer Treat Rep198771109419442820571

- RothBJJohnsonDHEinhornLHRandomized study of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine versus etoposide and cisplatin versus alternation of these two regimens in extensive small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the Southeastern Cancer Study GroupJ Clin Oncol19921022822911310103