Abstract

Background

A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the epidermal growth factor (EGF) gene (rs4444903) has been associated with increased risk of cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between the EGF SNP genotype and the development and prognosis of HCC, in a Japanese population.

Methods

Restriction fragment-length polymorphism was used to determine the presence of the EGF SNP genotype in 498 patients, including 208 patients with HCC. The level of EGF messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression in cancerous tissues was measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. The correlation between the EGF SNP genotype and prognosis was statistically analyzed in the patients with HCC.

Results

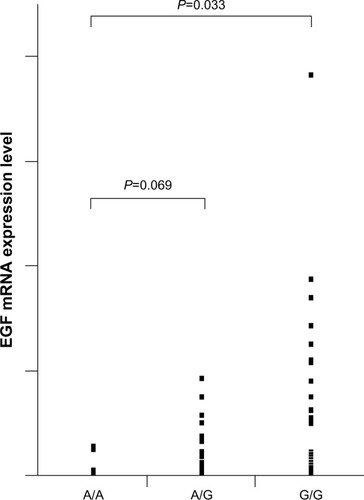

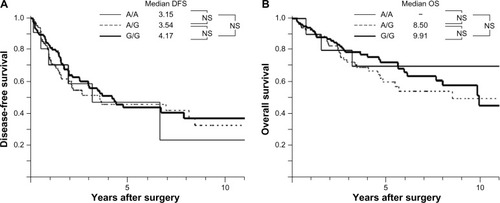

The proportion of the A/A, A/G, and G/G genotypes were 5.3%, 42.8%, and 51.9%, respectively, in the patients with HCC, whereas in those without HCC, they were 8.6%, 35.9%, and 55.5%, respectively, revealing that the odds ratio (OR) of developing HCC was higher in patients with a G allele (OR =1.94, P=0.080 for A/G patients and OR =1.52, P=0.261 for G/G patients, as compared with A/A patients). In particular, when the analysis was limited to the 363 patients with hepatitis C, the OR for developing HCC was 3.54 (P=0.014) for A/G patients and was 2.85 (P=0.042) for G/G patients, as compared with A/A patients. Tumoral EGF mRNA expression in G/G patients was significantly higher than that in A/A patients (P=0.033). No statistically significant differences were observed between the EGF SNP genotype and diseasefree or overall survival.

Conclusion

The EGF SNP genotype might be associated with a risk for the development of HCC in Japanese patients but not with prognosis. Of note, the association is significantly stronger in patients with hepatitis C, which is the main risk factor for HCC in Japan.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer in men and the seventh in women and the third most common cause of death from cancer worldwide.Citation1 The regions of high incidence for this disease are generally Eastern and South Eastern Asia and Middle and Western Africa. Because most patients who develop HCC are affected with viral hepatitis and require follow up for decades, it is necessary to analyze new molecular markers that can be used to identify high-risk populations that may be suitable for more intensive screening or prevention strategies.Citation2

Currently, molecular alterations in tumors are being scrutinized at a genome-wide scale, covering different dimensions, such as gene expression, epigenetic changes, chromosomal aberrations, and more recently, next generation sequencing.Citation3 As for HCC, there have been many reports regarding molecular markers associated with the development of HCC.Citation2,Citation4–Citation6 These molecular markers could be useful in the clinic; however, racial differences have been reported, and these need to be examined more thoroughly.Citation5–Citation7

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) was isolated in 1962 and has been shown to stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of epidermal and epithelial tissues, via binding to the EGF receptor (EGFR).Citation8–Citation10 EGF is well known to be associated with various malignant tumors, such as melanoma and esophageal carcinoma, via autocrine or paracrine pathways.Citation11,Citation12 Shahbazi et alCitation13 identified a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) involving A to G transition at position 61 in the 5′ untranslated region of the EGF gene (rs4444903) and demonstrated that the G/G genotype was associated with an increased risk of developing malignant melanoma compared with the A/A genotype.

Recently, Tanabe et alCitation2 showed that the G/G genotype was correlated with an increased risk of developing HCC in both a mixed North American population and a Caucasian French population and that serum and liver tissue EGF levels were higher in A/G and G/G patients as compared with A/A patients. Furthermore, Abu Dayyeh et alCitation7 expanded this study with a larger cohort and demonstrated the differences in the distribution of polymorphisms by race and by the incidence of HCC. However, conflicting results have been reported from the People’s Republic of China, with two studies showing an association between the G allele and HCC risk,Citation14,Citation15 while another report found no association between the EGF polymorphism and HCC risk.Citation16

Thus far, there has been no report examining the EGF genotype and its association with HCC in a Japanese population. Even though the allelic distribution is expected to be similar between Chinese and Japanese patients, hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the major risk factor for HCC in Japan, whereas hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the major risk factor in the People’s Republic of China and other Eastern countries. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between the EGF SNP and risk of HCC. In addition, to our knowledge, this is the first report to analyze the EGF SNP as a prognostic factor for HCC patients.

Materials and methods

Study population and specimens

A total of 498 patients with liver disease were single ethnic Japanese and retrospectively enrolled in this study at Nagoya University Hospital during the period from 1994 to 2010, with exclusion of autoimmune liver disease, hereditary liver diseases, including Wilson’s disease, drug-related hepatitis, and obstructive jaundice. Of these, 208 patients were diagnosed histologically as having HCC and underwent liver resection, and the other 290 patients were followed up for either hepatitis or liver cirrhosis. Patient’s clinicopathological parameters were collected retrospectively from our database. Postoperative disease-free and overall survival in the 208 patients who underwent liver resection were calculated, and the median follow-up duration was 40.9 months (range 0.4–209.0 months).

In the 208 patients who underwent liver resection, the collected samples from the resected specimen were stored immediately in liquid nitrogen at −80°C until analysis. Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was obtained by digestion with proteinase K, recombinant, PCR grade (F Hoffman-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) followed by phenol/chloroform (Ultra-Pure™ Phenol, Life Technologies Corp, Carlsbad, CA, USA/Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd, Osaka, Japan) extraction. Total ribonucleic acid (RNA) was isolated from each of the frozen samples with the RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For the 290 patients without liver resections, genomic DNA was extracted from 150 μL of whole blood, using a commercial kit (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit; Qiagen).

As required by the Institutional Review Board of Nagoya University, which provided ethical approval, written and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

EGF genotyping

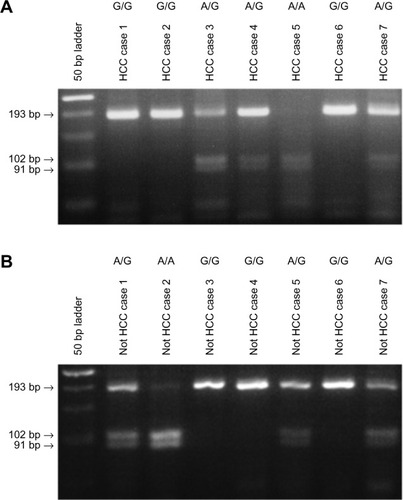

The EGF SNP rs4444903 was analyzed by using restriction fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP), as described previously.Citation13 In brief, genomic DNA was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using the GeneAmp® PCR System 9700 (Life Technologies Corp, Carlsbad, CA, USA). It was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles at 95°C for 30 seconds, at 51°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension step of 7 minutes at 72°C, to amplify nucleotide positions −78 to +164 of the EGF gene. The following primers were used, forward: 5′-TGTCACTAAAGGAAAGGAGGT-3′ and reverse: 5′-TTCACAGAGTTTAACAGCCC-3′ (STAR Oligo, Rikaken Co., Ltd, Nagoya, Japan). Then, 20 μL of PCR product was digested overnight with 5 units of AluI (F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd) at 37°C, separated by electrophoresis in a 3% agarose gel (Agarose for DNA/RNA, NIPPON Genetics Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide (Boehringer, Mannheim, IN, USA). AluI digestion of the 242 base pair (bp) PCR product containing the 61*G allele produced 15, 34, and 193 bp fragments, while digestion of the 61*A allele produced 15, 34, 91, and 102 bp fragments. The experiment was repeated twice for each sample to ensure accuracy.

Determining EGF mRNA expression

The EGF messenger RNA (mRNA) in the HCC tissues was measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Total RNA from each sample was used to synthesize complementary DNA by single-strand reverse transcription (M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase; Life Technologies Corp). The level of EGF mRNA was expressed as the ratio of EGF mRNA PCR product to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in each sample for standardization. The primer sequences used were EGF forward: 5′-CTTGTCATGCTGCTCCTCCT-3′ and reverse: 5′-GAGGGCATATGAAAGCTTCG-3′. The expression of GAPDH was quantified using the primer, forward: 5′-AACGGCTCCGGCATGTGCAA-3′ and reverse: 5′-GGCTCCTGTGCAGAGAAAGC-3′. Real-time detection of the emission intensity of SYBR® Green I (SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II, Takara Bio Inc, Otsu, Japan) was performed with an ABI Prism® 7000 Sequence Detection System (Life Technologies Corp). All PCR reactions were performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 40 seconds. The experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure accuracy.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test was used to determine whether the observed genotype frequencies were consistent with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. The statistical differences between groups were evaluated using the chi-square test for qualitative variables and unpaired t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) for quantitative variables. Comparisons of groups with regard to the odds of HCC were made using a logistic regression model, and age and sex were included as covariates, in addition to genotype, in adjusted analysis. The overall survival and disease-free survival rates were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the difference was analyzed using the logrank test. Independent prognostic factors were analyzed with the Cox proportional hazards regression model, in a stepwise manner. The statistical analysis was performed using JMP® 9 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). The presence of a statistically significant difference was denoted by P<0.05.

Results

EGF genotyping of patients

RFLP was used to determine the EGF SNP genotype in 208 patients with HCC and 290 patients with either hepatitis or liver cirrhosis ( and ). The ratios of A/A, A/G, and G/G genotypes were 5.3%, 42.8%, and 51.9%, respectively, in the 208 patients with HCC, whereas in the 290 patients without HCC, the ratios were 8.6%, 35.9%, and 55.5%, respectively. The frequencies of the EGF polymorphism in this study population were consistent with Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P=0.864).

Figure 1 EGF SNP was analyzed by using restriction fragment-length polymorphism, and the representative results are shown: (A) HCC patients and (B) not HCC patients with liver disease other than HCC, including hepatitis or cirrhosis patients.

Patient characteristics

Our Japanese population consisted of 208 patients with HCC and 290 patients without HCC, and their characteristics are shown in . There was a significant difference in the distribution of age (P<0.001) and sex (P<0.001) between the HCC group and those patients without HCC. There was also a significantly higher incidence rate of HCC in the HBV patients than in the HCV patients (P<0.001).

Table 1 Patient characteristics with or without HCC

The patient characteristics were also stratified by EGF genotype and are shown in . There were no significant differences in age and sex with respect to the EGF SNP. A total of 391 patients had HCV, and 64 patients had HBV, and there were no significant differences between these etiologies and EGF genotype (P=0.127).

Table 2 Patient characteristics, stratified by EGF genotype

EGF mRNA expression level

The presence of the G allele has been reported to increase the expression of EGF and may be one mechanism by which the EGF SNP increases the risk of HCC.Citation2 To examine the correlation between EGF genotype and its expression, the level of EGF mRNA in cancerous tissues were measured by real-time PCR. The relative ratios of A/G (P=0.069) and G/G (P=0.033) patients were significantly higher than that of A/A patients ().

Relative risk of developing HCC, based on EGF genotype

In order to explore the association between EGF genotype and the susceptibility of HCC development, the odds ratio (OR) for the risk of HCC was statistically analyzed, using the A/A genotype as a reference (). The proportions of A/A, A/G, and G/G genotypes were 5.3%, 42.8%, and 51.9%, respectively, in patients with HCC, whereas in patients without HCC, the ratios were 8.6%, 35.9%, and 55.5%, respectively, which revealed that the OR of developing HCC was 1.93 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.92–4.27, P=0.081) in the A/G patients and was 1.51 (95% CI: 0.73–3.30, P=0.268) in the G/G patients, compared with A/A patients. Importantly, after adjusting for age and sex, the ORs for the A/G and G/G genotypes were 2.57 (P=0.030) and 1.90 (P=0.133), respectively.

Table 3 Analysis of EGF genotype in a Japanese population

Next, we restricted the analysis to patients with HCV, which is the most common risk factor for HCC in Japan (). This analysis demonstrated a significant association between the EGF genotype and risk of HCC. The OR was 3.54 (P=0.014) in the A/G patients and 2.85 (P=0.042) in the G/G patients in the crude analysis, and was 7.58 (P<0.001) in the A/G patients and 4.61 (P=0.008) in the G/G patients in the adjusted analysis.

Table 4 Analysis of EGF genotype in Japanese patients with HCV

We also analyzed the risk limited to HBV, which is the second most frequent cause of HCC in Japan and accounts for about 15% of cases. The proportions of A/A, A/G, and G/G genotypes were 11.4%, 40.9%, and 47.7%, respectively, in patients with both HBV and HCC, while the proportions were 3.1%, 43.1%, and 53.9%, respectively, in patients with both HCV and HCC. Even though the A allele tended to occur more frequently in HBV patients with HCC, there was no significant difference compared with that proportion in patients with both HCV and HCC (P=0.136). In addition, the EGF genotype was not a significant risk factor for HCC in HBV patients (data not shown).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of clinicopathological factors for overall survival

In the univariate analysis of various clinicopathological parameters for overall survival, tumor size (≥3 cm) (P=0.009), vascular invasion (P<0.001), pathological stage III or IV (P=0.048), and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level (≥20 ng/mL) (P=0.015) were all significant risk factors for poor overall survival (). In the multivariate analysis, tumor size, vascular invasion, and AFP level were all independent risk factors for poor survival. No statistically significant differences were observed between the EGF SNP genotype or EGF mRNA expression and overall survival, and the disease-free and overall survival stratified by EGF SNP, in the resected HCC patients, are shown in .

Figure 3 (A) DFS based on EGF SNP in HCC patients and (B) OS based on EGF SNP in HCC patients.

Table 5 Univariate and multivariate analysis of clinicopathological factors for overall survival

Discussion

Hepatocarcinogenesis is thought to be deeply associated with chronic HBV or HCV infection, and in fact, a certain proportion of chronically infected HBV and HCV individuals will develop HCC. Thus, multiple genetic and epigenetic factors may affect HCC development in this background.Citation17 Among these genetic alterations, the dysregulation of EGF/EGFR signaling pathway is thought to be one of the most important factors in early hepatocarcinogenesis.Citation18,Citation19

Previously, it has been reported in several studies that the distribution of the EGF polymorphism varies by race.Citation2,Citation7,Citation14,Citation16,Citation20 In our Japanese population, the allelic frequencies of the G allele and A allele were 0.73 and 0.27, respectively, which is very similar to what has been reported for Chinese and African Americans. This distribution is strikingly different from Caucasians though, for whom the allelic frequencies of the G and A alleles are roughly 0.40 and 0.60, respectively. It is interesting to speculate that these differences in distribution might explain the high incidence of HCC in East Asia and Africa, but this requires further study.

A meta-analysis of five studies examining the EGF genotype and HCC risk concluded that the G allele was a risk factor for HCC, independently of ethnicity and etiology.Citation21 This is in contrast to three previous studies examining the association between the EGF genotype and risk of HCC in Chinese patients with HBV.Citation14–Citation16 However, a more recent meta-analysis examined six studies including these Chinese studies and revealed a significant association between the G allele and HCC risk, and concluded that the original discrepancy was probably due to the fact that these were single case-control studies with small sample sizes.Citation22 In addition, when the researchers analyzed all eight published studies on the EGF polymorphism and HCC risk, they found that the 61G allele was a risk factor for HCC, while the 61A allele was protective. Not surprisingly, the A/A genotype occurs in less than 10% of Asians and African Americans but is present in roughly 30% of Caucasians.

It is difficult to explain why the risk of developing HCC is higher in patients with the A/G genotype rather than with the G/G genotype. One would expect that risk of HCC would increase with the number of copies of the G allele; however, it has been observed occasionally, in other studies, that the OR was higher for A/G patients.Citation2,Citation14,Citation20 We suspect that this might be due to relatively small sample sizes. Regardless, the A/G and G/G patients had a higher risk of developing HCC than the patients with the A/A genotype, in our Japanese population. In addition, the ORs that we report here are higher than those observed in studies examining other polymorphisms,Citation23–Citation25 and this observation might suggest that the EGF SNP strongly contributes to the development of HCC. Also, given that Japan is an insular country and therefore a genetically isolated area,Citation26 the high risk identified by the EGF SNP in this Japanese population might suggest for more disease specificity. Thus, our observations overall strengthen the previous assertion that the EGF SNP is associated with the development of HCC.

Of note, when the analysis was limited to patients with HCV and adjusted for age and sex, the risk of developing HCC increased dramatically in the A/G and G/G patients. This finding is of particular importance as HCV is the main risk factor for HCC in Japan. In addition, several recent mechanistic studies support this finding. First, EGFR was recently shown to be a host factor for HCV cellular entry when it was found that EGFR signaling leads to assembly of the host tetraspanin receptor complex.Citation27,Citation28 The ligands that activate EGFR, especially EGF, therefore increase HCV cellular entry,Citation27 and the EGF SNP is known to increase liver EGF levels.Citation2

The association between the EGF genotype and prognosis so far has not been described in HCC patients and remains controversial in other malignancies, such as glioma and esophageal carcinoma.Citation29–Citation31 In this study, no statistical association was found between the EGF genotype and both disease-free and overall survival, in HCC patients. This result could be explained by the fact that the prognosis of HCC, as opposed to other malignancies, is subject to various individual conditions, such as cirrhosis, leading to multicentric carcinogenesis and residual liver function.Citation32 Interestingly, EGF is part of a gene expression signature associated with poor overall survival in HCC patients who have had a resection and in cirrhosis patients.Citation33,Citation34 This signature was derived from the surrounding nontumoral liver tissue and might help explain why the increased tumoral EGF expression seen in our A/G and G/G patients was not associated with survival. It might be that EGF expression alone is not powerful enough to predict prognosis, or it could be that EGF expression in the surrounding, nontumoral tissue will have greater prognostic value. Consistent with this, Falleti et alCitation35 reported that the EGF genotype associates with advanced fibrosis at a young age in HCV patients. They hypothesized that the EGF polymorphism is responsible for a more rapid disease progression early in the course of HCV infection, which would be consistent with its role in cellular entry.

In conclusion, the allelic frequencies of the EGF polymorphism in Japanese patients were similar to those reported previously for other high-risk HCC groups, including Chinese and African Americans. The A/G and G/G genotypes were associated with an increased risk of HCC, especially in HCV patients, in whom increased EGF levels might lead to a more rapid disease progression. We suggest that more intensive follow up of HCV patients with the G allele might lead to earlier diagnosis and better outcomes for HCC.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FerlayJShinHRBrayFFormanDMathersCParkinDMEstimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008Int J Cancer2010127122893291721351269

- TanabeKKLemoineAFinkelsteinDMEpidermal growth factor gene functional polymorphism and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosisJAMA20082991536018167406

- HoshidaYMoeiniAAlsinetCKojimaKVillanuevaAGene signatures in the management of hepatocellular carcinomaSemin Oncol201239447348522846864

- LiMZhaoHZhangXInactivating mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in hepatocellular carcinomaNat Genet201143982882921822264

- WangYKatoNHoshidaYInterleukin-1beta gene polymorphisms associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus infectionHepatology2003371657112500190

- JinFXiongWJJingJCFengZQuLSShenXZEvaluation of the association studies of single nucleotide polymorphisms and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic reviewJ Cancer Res Clin Oncol201113771095110421240526

- Abu DayyehBKYangMFuchsBCHALT-C Trial GroupA functional polymorphism in the epidermal growth factor gene is associated with risk for hepatocellular carcinomaGastroenterology2011141114114921440548

- CohenSIsolation of a mouse submaxillary gland protein accelerating incisor eruption and eyelid opening in the new-born animalJ Biol Chem19622371555156213880319

- CarpenterGCohenSEpidermal growth factorAnnu Rev Biochem197948193216382984

- FisherDALakshmananJMetabolism and effects of epidermal growth factor and related growth factors in mammalsEndocr Rev19901134184422226349

- StoscheckCMKingLEJrRole of epidermal growth factor in carcinogenesisCancer Res1986463103010373002608

- YoshidaKKyoETsudaTEGF and TGF-alpha, the ligands of hyperproduced EGFR in human esophageal carcinoma cells, act as autocrine growth factorsInt J Cancer19904511311352298497

- ShahbaziMPravicaVNasreenNAssociation between functional polymorphism in EGF gene and malignant melanomaLancet2002359930439740111844511

- LiYXieQLuFAssociation between epidermal growth factor 61A/G polymorphism and hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility in Chinese patientsLiver Int201030111211819840254

- ChenKWeiYYangHLiBEpidermal growth factor +61 G/A polymorphism and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese populationGenet Test Mol Biomarkers201115425125521186997

- QiPWangHChenYMSunXJLiuYGaoCFNo association of EGF 5′UTR variant A61G and hepatocellular carcinoma in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infectionPathology200941655556019900104

- LlovetJMBruixJMolecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinomaHepatology20084841312132718821591

- MorimitsuYHsiaCCKojiroMTaborENodules of lessdifferentiated tumor within or adjacent to hepatocellular carcinoma: relative expression of transforming growth factor-alpha and its receptor in the different areas of tumorHum Pathol19952610112611327557946

- KömüvesLGFerenAJonesALFodorEExpression of epidermal growth factor and its receptor in cirrhotic liver diseaseJ Histochem Cytochem200048682183010820155

- AbbasEShakerOAbd El AzizGRamadanHEsmatGEpidermal growth factor gene polymorphism 61 A/G in patients with chronic liver disease for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a pilot studyEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol201224445846322293333

- YangZWuQShiYNieYWuKFanDEpidermal growth factor 61A/G polymorphism is associated with risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysisGenet Test Mol Biomarkers20121691086109122852842

- ZhongJHYouXMGongWFEpidermal growth factor gene polymorphism and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysisPLoS One201273e3215922403631

- MikiDOchiHHayesCNVariation in the DEPDC5 locus is associated with progression to hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C virus carriersNat Genet201143879780021725309

- KumarVKatoNUrabeYGenome-wide association study identifies a susceptibility locus for HCV-induced hepatocellular carcinomaNat Genet201143545545821499248

- ZhangCTianYPWangYGuoFHQinJFNiHhTERT rs2736098 genetic variants and susceptibility of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Chinese population: a case-control studyHepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int2013121747923392802

- KatohTManoSIkutaTGenetic isolates in East Asia: a study of linkage disequilibrium in the X chromosomeAm J Hum Genet200271239540012082643

- LupbergerJZeiselMBXiaoFEGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapyNat Med201117558959521516087

- ZonaLLupbergerJSidahmed-AdrarNHRas signal transduction promotes hepatitis C virus cell entry by triggering assembly of the host tetraspanin receptor complexCell Host Microbe201313330231323498955

- CostaBMFerreiraPCostaSAssociation between functional EGF+61 polymorphism and glioma riskClin Cancer Res20071392621262617473192

- PintoGRYoshiokaFKClaraCAAssociation study of an epidermal growth factor gene functional polymorphism with the risk and prognosis of gliomas in BrazilInt J Biol Markers200924427728120108217

- LanutiMLiuGGoodwinJMA functional epidermal growth factor (EGF) polymorphism, EGF serum levels, and esophageal adenocarcinoma risk and outcomeClin Cancer Res200814103216322218483390

- KobayashiTIshiyamaKOhdanHPrevention of recurrence after curative treatment for hepatocellular carcinomaSurg Today Epub20121228

- HoshidaYVillanuevaAKobayashiMGene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinomaN Engl J Med2008359191995200418923165

- HoshidaYVillanuevaASangiovanniAPrognostic gene expression signature for patients with hepatitis C-related early-stage cirrhosisGastroenterology201314451024103023333348

- FalletiECmetSFabrisCAssociation between the epidermal growth factor rs4444903 G/G genotype and advanced fibrosis at a young age in chronic hepatitis CCytokine2012571687322122913