Abstract

Background

The use of pharmacogenomic testing in the clinical setting has the potential to improve the safety and effectiveness of drug therapy, yet studies have revealed that physicians lack knowledge about the topic of pharmacogenomics, and are not prepared to implement it in the clinical setting. This study further explores the pharmacogenomic knowledge deficit and educational resource needs among physicians.

Materials and methods

Surveys of primary care physicians, cardiologists, and psychiatrists were conducted.

Results

Few physicians reported familiarity with the topic of pharmacogenomics, but more reported confidence in their knowledge about the influence of genetics on drug therapy. Only a small minority had undergone formal training in pharmacogenomics, and a majority reported being unsure what type of pharmacogenomic tests were appropriate to order for the clinical situation. Respondents indicated that an ideal pharmacogenomic educational resource should be electronic and include such components as how to interpret pharmacogenomic test results, recommendations for prescribing, population subgroups most likely to be affected, and contact information for laboratories offering pharmacogenomic testing.

Conclusion

Physicians continue to demonstrate pharmacogenomic knowledge gaps, and are unsure about how to use pharmacogenomic testing in clinical practice. Educational resources that are clinically oriented and easily accessible are preferred by physicians, and may best support appropriate clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics.

Introduction

The application of genomics to clinical care has grown tremendously over the last decade. Nearly every baby born in the US undergoes a continually expanding battery of genetic tests within days of birth,Citation1 gene-expression patterns are routinely analyzed to predict prognosis and guide treatment of malignancies,Citation2 and most recently, whole-genome sequencing has been successfully applied to solve diagnostic dilemmas not amenable to more traditional approaches.Citation3 However, many physicians have reported inadequate knowledge about genetics and a lack of confidence in using genomic-based technologies in the clinic.Citation4–Citation8 This educational gap has been cited as a substantial barrier to the implementation of genomic technologies in clinical care.Citation9–Citation15

The clinical availability of pharmacogenomic tests, ie, tests that detect inherited genetic variations that influence individual response to drugs, has grown rapidly. This growth has been fueled in part by compelling statistics on adverse drug reactions (ADRs); ADRs occur in nearly 10% of patients taking prescription medications in the ambulatory settingCitation16 and cause an estimated 100,000 deaths each year in hospitalized patients in the US.Citation17 Genetic differences account for a substantial amount of patient variability in drug response and disposition,Citation18 and more than a quarter of primary care patients are taking a medication that commonly causes ADRs and is under the control of genetically variable factors.Citation19 In an effort to inform prescribers about the potential for ADRs, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has steadily updated the labeling of drugs that are subject to variable patient response in those carrying certain genetic variations.Citation20 The labeling of more than 100 drugs now contains such pharmacogenomic information. Approximately 25% of outpatients are being treated with a medication that includes pharmacogenomic information in the labeling.Citation21

Despite the relatively common practice of prescribing drugs with pharmacogenomic properties, most physicians report the same unfamiliarity with pharmacogenomic testing as they do with genomic technologies in general.Citation22,Citation23 Few primary care physicians believe they are well informed about the role of pharmacogenomic testing in therapeutic decision making, and a majority report that they are uncomfortable ordering a pharmacogenomic test.Citation22,Citation23

Several types of educational resources have been developed with the goals of familiarizing physicians and other health professionals with pharmacogenomics, increasing the appropriate clinical use of pharmacogenomic testing, targeting therapy to responsive patients, and decreasing the occurrence of certain preventable ADRs.Citation24–Citation33 These resources include stand-alone continuing medical education programs, print materials like brochures and fact sheets, and point-of care resources, such as integrated clinical decision support. To inform the continued development of pharmacogenomic resources that will be most useful for physicians, we conducted a survey of physicians in three specialty disciplines (primary care, psychiatry, and cardiology). Our goal was to better understand prescribing behaviors and physician experience with pharmacogenomic testing, and to explore physicians’ preferred characteristics of an ideal pharmacogenomics resource.

Materials and methods

Survey development and sample recruitment

Survey questions were developed collaboratively and subjected to several rounds of revision by staff in the American Medical Association (AMA) Science and Biotechnology and Market Research groups. Question development was informed by reviews of clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics and previous surveys of physicians,Citation22,Citation23,Citation34–Citation36 and by existing AMA staff expertise. The survey consisted of approximately 30 questions exploring knowledge and attitudes about pharmacogenomics, and ten demographic questions. Question types were 1) Likert-type scale, using the categories “extremely”, “very”, “somewhat”, “not very”, and “not at all” to report importance of issues considered when choosing appropriate drug-therapy/dosage regimens and familiarity with pharmacogenomics, and the categories “strongly agree”, “somewhat agree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “somewhat disagree”, and “strongly disagree” to indicate confidence in knowledge of the influence of patient genetics on the response to drug therapy; 2) semantic differential scale type, in which respondents were asked preferences for educational resource format on scale of 1–5, with 1 being most preferred and 5 being least preferred; and 3) multiple-choice questions about pharmacogenomic training, pharmacogenomic test-ordering behavior, drugs subject to variable clinical response due to genetic variation, currently consulted pharmacogenomic resources, content to be included in resources, preferred source to develop educational resources, and demographics. Respondents were allowed to enter more than one answer on multiple-choice questions, unless only one answer was appropriate, such as in “yes/no” questions. Some multiple-choice questions included the choice “other”, with a “please specify” request allowing entry of free text. The complete survey is available in the Supplementary material section.

Survey questions were programmed into the Qualtrics (Provo, UT, USA) survey program to develop an online survey site. A survey invitation was sent in October 2011 through Epocrates (San Mateo, CA, USA) to US office-based physicians between the ages of 25 and 64 years who use the service; the invitation included a link to the online survey. The survey was terminated for respondents indicating that they specialized in an area other than primary care, psychiatry, or cardiology. Primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and cardiologists were targeted because collectively they care for patients with a wide array of conditions, a number of which may be treated with drugs that are known to elicit variable responses in patients with certain genetic variations, and because those specialties are not as routinely reliant on pharmacogenomic testing as are some specialties, such as oncology. The survey was fielded for approximately 2 weeks. A total of 305 respondents met the demographic and specialty criteria, but five did not complete the entire survey. The survey was terminated when 300 primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and cardiologists had completed it. The survey was anonymous; respondent names were not collected.

Data analysis

Survey data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). To determine significance, t-tests were used for means and z-tests for column proportions, both with a 95% confidence level. In some cases, categories of Likert-type and semantic differential scale responses were collapsed, eg, combining “extremely important” and “very important”, combining “strongly agree” and “somewhat agree”, and combining responses of 1 and 2 on a 1–5 preference scale. For cases in which response categories were combined, notation is included in the corresponding figure or table. Participant characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Study-group characteristics

Characteristics of survey participants are summarized in . Of 300 physicians, approximately 60% were primary care physicians (including family physicians, general physicians, and internists); the remaining 40% of participants were split nearly equally between psychiatrists and cardiologists. Participants had a mean of 10.3 (±1.59) years in postresidency/fellowship practice, and spent a mean of 48.6 (±7.51) hours per week in direct patient contact. More than three-quarters of participants used smartphones and/or computers to access health care-related information. Approximately three- quarters of primary care physician and cardiologist respondents, and approximately half of psychiatrist respondents, used an electronic medical record (EMR) system. Comparison with AMA Physician Masterfile data showed that sex and geographic region of the survey sample were generally representative of the physician population. Survey participants tended to be younger than the general physician population, with participants aged 25–34 and 35–44 years overrepresented, and participants aged 45–54 years underrepresented among the respondents.

Table 1 Characteristics of survey population (n=300)

Prescribing attitudes

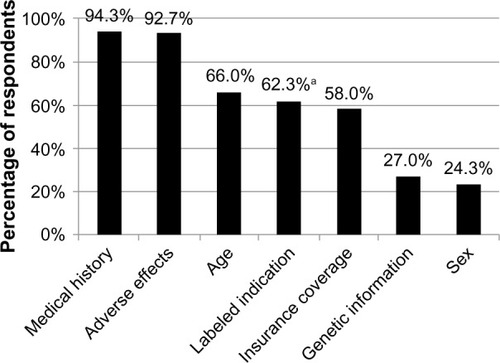

To understand further the relative importance physicians place on genetic information when making decisions about drug therapy, survey participants were asked to report how much importance they place on several factors, including genetic information, when choosing drug therapy and/or dosing regimens. Medical history and adverse effects were the factors most commonly cited by respondents as extremely or very important (94.3% and 92.7%, respectively), followed by age, labeled indication, and whether the drug is covered by insurance (66.0%, 62.3%, and 58.0%, respectively) (). A patient’s genetic information was reported as extremely or very important by only 27.0% of respondents (); an approximately equal number of respondents (28.0%) reported genetic information as not very or not at all important (not shown).

Figure 1 Factors cited as extremely or very important by physician respondents when choosing appropriate drug therapy or dosage.

Knowledge of pharmacogenomics

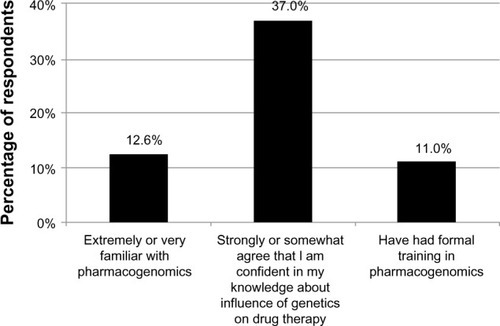

When asked to rank their familiarity with pharmacogenomics, 12.6% of respondents reported being extremely or very familiar with the topic (). After reporting their familiarity with pharmacogenomics, participants encountered the following statement: “Pharmacogenomics is the influence of genetic differences on human variability in drug response.” They were then asked if they agreed that they were confident in their knowledge of the influence of genetics on drug therapy; 37.0% of respondents reported that they strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement (). Only 11% reported that they had received formal training in pharmacogenomics (); medical school (66.7%), residency training (57.6%), and continuing medical education (CME) programs (48.5%) were the most commonly cited settings in which the training had occurred (not shown).

Figure 2 Familiarity with, confidence in and knowledge of, and training in pharmacogenomics, as reported by physician respondents. “Formal training” was defined as medical school, residency, or continuing medical education.

To determine whether self-reported confidence in knowledge of the influence of genetics on drug therapy was an accurate indicator of actual knowledge, survey participants were asked to indicate, to the best of their knowledge, whether each of several commonly prescribed drugs (presented in a list format) “elicit substantially variable responses due to a patient’s genetic background.” Wide variation in responses was received, roughly correlating with specialty (). For example, 86.4% and 64.4% of cardiologists correctly indicated that clopidogrel and warfarin (both commonly prescribed to treat cardiology-related conditions), respectively, elicit variable responses due to genetic background. Similarly, 43.3% and 21.7% of psychiatrists correctly indicated that carbamazepine and atomoxetine (both commonly prescribed to treat psychiatric-related conditions), respectively, elicit variable responses due to genetic background. Each specialty group showed knowledge deficits. For example, only 7% and 5% of primary care and cardiologist respondents, respectively, correctly indicated that metoprolol (used primarily to treat hypertension) elicits variable responses based on genetic background. Significantly more psychiatrists than primary care physicians or cardiologists (41.7% versus 19.3% and 6.8%, respectively) reported that they did not know whether one or more of the drugs could elicit a substantially variable response due to a patient’s genetic background.

Table 2 Proportion of respondents indicating that the drug listed could elicit a substantially variable response due to a patient’s genetic background

Pharmacogenomic test ordering

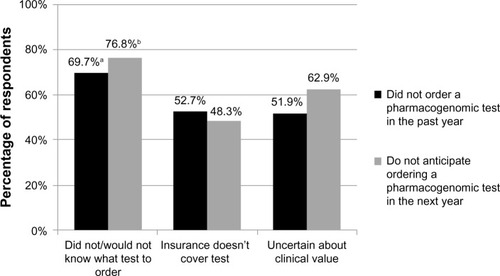

Nearly 20% of survey respondents indicated that they had ordered a pharmacogenomic test during the last year, with significantly more cardiologists than psychiatrists having ordered a test (32.2% versus 11.7%, P<0.05; not shown). When those who indicated that they had not ordered a pharmacogenomic test in the past year were asked why they had not, the most common answers were not knowing what test to order (69.7%), lack of insurance coverage (52.7%), and uncertainty about the clinical value of the test (51.9%) (). Other answers were not applicable for patients (17.8%), patient declined test (5.0%), and privacy concerns (5.0%) (not shown). Significantly more primary care physicians than cardiologists reported that they did not know what test to order (75.0% versus 52.5%, P<0.05).

Figure 3 Reasons most commonly cited by physician respondents for not ordering a pharmacogenomic test in the past year, and for not anticipating ordering a pharmacogenomic test in the next year.

Respondents also were asked whether they anticipated ordering a pharmacogenomic test in the next year, with 49.7% answering in the affirmative; no significant differences were noted among the specialties. Those who indicated that they did not plan to order a pharmacogenomic test in the next year were asked why they would not. The most common responses were similar to reasons cited for not having ordered a test in the past year: 76.8% indicated they would not know what test to order, 62.9% indicated that they would be uncertain of the test’s clinical value, and 48.3% indicated that insurance would not cover the test (). Other responses were not applicable for patients (17.9%), patient likely to decline test (10.6%), and privacy concerns (6.6%) (not shown). Significantly more primary care physicians and psychiatrists than cardiologists reported that they would not know what test to order (84.6% and 83.9%, respectively, versus 44.8%; P<0.05).

For those who indicated that they had ordered a pharmacogenomic test in the past year, we asked, in the form of a free-text field, what type of test was ordered. Among those who answered the question, 43% named tests associated with clopidogrel and warfarin. Approximately 25% of respondents named a test that is not a pharmacogenomic test, eg, “BRCA”, “cystic fibrosis”, “hemochromatosis”, and “Huntington’s disease”.

Current pharmacogenomic resources

To gain an understanding of the pharmacogenomic educational resources currently used by physicians, survey participants were asked to indicate from a list of resource types which type they most often consult when they have questions about pharmacogenomics. Scientific literature (58.0%), the Internet (49.3%), professional society literature/recommendations (47.3%), and peer discussions (41.7%) were the most commonly cited (). Less commonly cited were laboratory directors/personnel (25.0%), drug labeling (20.7%), the FDA website (17.7%), and insurance companies/payers (11.3%) (). A small percentage of respondents (14.3%) indicated that they had not consulted any resources. Primary care physicians were significantly more likely than cardiologists to have consulted a laboratory director/personnel (29.8% versus 11.9%, P<0.05), and primary care physicians and psychiatrists were significantly more likely than cardiologists to have consulted the FDA website (18.8% and 26.7%, respectively, versus 5.1%; P<0.05). When asked whether currently available resources enable them to access the information they need or want to know, 43.0% of survey respondents answered yes.

Table 3 Resources currently consulted when questions arise about pharmacogenomics

Ideal pharmacogenomic resource

When asked to indicate from a list of content topics which should be included in an ideal pharmacogenomic resource, the most commonly cited answers were how to interpret pharmacogenomic test results (88.4%), recommendations for prescribing (88.1%), effect of genetic variation on mechanism of drug action (79.9%), and demographics of populations likely to carry variations (76.9%) (). Other content preferences among respondents included references such as scientific literature (69.0%), a list of laboratories offering testing (63.9%), and a description of pharmacogenomic information in drug labeling (62.2%) (). Other responses, submitted as free text, included the price of tests and whether they were covered by insurance. Significantly more psychiatrists than cardiologists indicated that information on how to interpret pharmacogenomic test results (96.7% versus 82.5%, P<0.05) and a description of pharmacogenomic information in drug labeling (75.0% versus 52.5%, P<0.05) should be included in an ideal resource.

Table 4 Preferred characteristics of an ideal pharmacogenomic educational resource

Survey participants were asked to rate on a scale of 1–5, with 1 being most preferred and 5 being least preferred, what type of format they would prefer for an ideal pharmacogenomic resource. A web-based format was ranked as a 1 or 2 by 67.7% of respondents, mobile application for smartphone or tablet was ranked as 1 or 2 by 56.2% of respondents, and incorporated within an EMR system was ranked as a 1 or 2 by 34.0% of respondents (). Primary care physicians were significantly more interested in EMR incorporation than were psychiatrists (41.2% rating it as a 1 or 2 versus 16.6% rating is as a 1 or 2, P<0.05). Print materials and pop-up reminders within prescribing systems were least preferred. Participants were given the opportunity to name other preferred resource formats using a free-text field; answers included a telephone hotline, pharmacy feedback to physicians, and continuing medical education events (not shown).

Survey participants also were asked to indicate which of the listed organization or institution types would be their preferred source to develop a pharmacogenomic resource. Respondents reported that they most preferred a health care-related software company (66.9%) (); Epocrates was included as an example of a health care-related software company. Professional/specialty societies (19.4%), government (6.7%), and health insurance companies (5.7%) were also named (). Answers written in as free text included “pharmacy experts” and a number of specific medical specialty societies.

Discussion

The pharmacogenomic knowledge deficit among physicians suggests the need for educational resources that will support clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics when appropriate. To determine what type of resource may be most valuable to physicians, we sought to understand further their knowledge and attitudes about pharmacogenomics, use of pharmacogenomic testing, use of current educational resources, and preferred characteristics of an ideal educational resource among physicians in selected specialties. Results suggest that physicians continue to experience a pharmacogenomics knowledge deficit, and prefer educational resources that are clinically oriented.

Assessment of attitudes and knowledge gaps

Given the imperative for safe and effective drug therapy, the importance that physicians place on a patient’s medical history (diagnosis, reason for drug therapy) and the potential for adverse effects (possible drug interactions, past drug intolerance or adverse event) when making prescribing decisions is not surprising. Other studies examining factors that influence prescribing decisions have reported similar results.Citation37,Citation38 However, since nearly all physicians believe genetic variations influence drug response,Citation22 it was somewhat unexpected that few respondents in our survey considered genetic information extremely or very important. Our study and others have shown deficiencies in physicians’ knowledge of the influence of genetics on drug therapy,Citation22,Citation23,Citation39,Citation40 so it is possible that physicians acknowledge the importance of genetic variation on drug response but that their gap in knowledge on the topic negatively impacts their attitude about its importance in prescribing decisions. Another possibility is that respondents considered medical history as being inclusive of genetic information. Similarly, adverse reactions often arise when a patient carries a genetic variation affecting drug metabolism or response, so respondents may have considered genetic information as contributing to the overall potential for adverse effects.

Our study shows that familiarity with the concept of pharmacogenomics remains low, with just 12.6% indicating that they were extremely or very familiar with it. Similarly, a study by Haga et al revealed that only 13% of respondents felt well informed about the role of pharmacogenomics in therapeutic decision making,Citation23 and Stanek et al showed that only approximately 10% of respondents felt they were adequately informed about the applicability of genetic testing to drug therapy.Citation22 Our study further reveals that there may be a misunderstanding about the meaning of the term “pharmacogenomics”; the number of respondents reporting that they were confident in their knowledge about the influence of genetics on drug response was several-fold higher than the number reporting familiarity with pharmacogenomics (). Few physicians may be aware that pharmacogenomics is, at its most basic, the influence of genetic variation on drug response. This possibility is supported by reported difficulties experienced by physicians and other health professionals asked to describe the concept of pharmacogenomics; confusion about the purpose of pharmacogenomic testing and the process of test ordering and interpretation was apparent among participants in Fargher et al.Citation41 In addition to the need for resources that can assist physicians in using pharmacogenomic technologies when clinically appropriate, our results point to the need for consistent terminology that makes it clear that in the clinical context, the term “pharmacogenomics” means the awareness that genetic variations could result in a patient’s suboptimal response to a drug.

Our direct assessment of pharmacogenomic knowledge by asking survey respondents to pick, from a list of commonly prescribed drugs, those that could elicit a substantially variable response based on a patient’s genetic background was consistent with the modest proportion reporting confidence in their knowledge of the influence of genetics on drug therapy. Answering correctly tended to correlate with specialty, ie, drugs commonly prescribed by a certain specialty were more likely to be identified by that specialty as potentially eliciting a variable response due to genetic background. Encouragingly, a large majority of cardiologists correctly identified clopidogrel as potentially eliciting a variable response (), perhaps due to a recently added boxed warning on its labeling noting that the drug is less effective in people who cannot metabolize it to its active form, and to heavy television marketing of the drug that included messaging about genetic variations that reduce its effectiveness. Important knowledge gaps were apparent, however. Few primary care physicians or cardiologists indicated that metoprolol has the potential for variable response, and only about half of primary care physicians indicated that clopidogrel and warfarin have the potential for variable response (). This is despite the fact that these three drugs are among the most commonly prescribed in the US.Citation42 We are not aware of other studies that have directly assessed physicians’ pharmacogenomic knowledge gaps, but our results are consistent with studies that have found physicians’ self-reported knowledge to be low.Citation22,Citation23,Citation39

Physicians who have embraced the utility of pharmacogenomic testing tend to be those who acknowledge receiving formal training in it (medical school, residency, or continuing medical education).Citation22 However, coursework covering pharmacogenomic concepts is limited in medical schools: only approximately a quarter of medical schools include more than 4 hours of pharmacogenomics coursework in their curricula, and three-quarters of medical schools consider their own pharmacogenomics curriculum to be poor or inadequate.Citation43 Several recommendations have been made to improve pharmacogenomics and more generally genomic training in medical school and residency programs.Citation44–Citation46 Similarly, it is thought that continuing medical education programs that are more integrated into the clinical routine and that emphasize applicable practical skills improvement are more likely to bring about sustained changes than are passive, stand-alone courses.Citation9,Citation10,Citation35 Suggested external forces that may drive the improvement of formal pharmacogenomic education are the inclusion of pharmacogenomic-focused questions on licensure examinations, the threat of malpractice litigation once pharmacogenomic information is included in drug labeling, and patients’ increasing interest in direct-to-consumer genetic testing services.Citation47

Clinical uptake of pharmacogenomics

Clinical integration of pharmacogenomic testing appears to be on the rise, based on the number of physicians who anticipate ordering a pharmacogenomic test in the next year. That number, nearly 50%, was more than twice the number reporting that they had ordered a pharmacogenomic test in the last year, and is similar to previously reported increases between pharmacogenomic test-ordering behavior in the recent past compared to anticipated pharmacogenomic test ordering.Citation22 However, when respondents were asked to name the pharmacogenomic tests they had ordered or anticipated ordering, a quarter named a genetic test not related to pharmacogenomics. This further underscores the notion that physicians may not understand the term “pharmacogenomics”, and calls into question whether the increase in the number of physicians who plan to order a “pharmacogenomic test” in the next year is a valid indicator of increasing clinical adoption. Accurate estimates of clinical adoption may be best accomplished by directly studying the number of pharmacogenomic tests ordered from several laboratories over time, rather than by relying on physicians’ recollection and anticipated behavior.

The lack of evidence supporting the clinical utility of pharmacogenomic testing is often cited as a barrier to its integration.Citation10,Citation34–Citation36,Citation48 In our survey, uncertainty about the clinical value of the test was cited as a reason for not having ordered or not anticipating ordering a pharmacogenomic test (), but it was not the most commonly cited reason. Rather, more physicians reported being unsure about what pharmacogenomic test to order, suggesting that the knowledge gap is a larger barrier among physicians than a perceived lack of evidence. Since nearly all physicians believe that genetic variations influence drug response,Citation22 it has been suggested that the knowledge gap may be more practical, such as not knowing what tests are available, where to order them, or how to interpret their results, rather than foundational.Citation4,Citation22 Selkirk et al demonstrated that physicians who have had experience caring for a patient who has undergone pharmacogenomic testing have a higher level of understanding of factors related to the genetic testing process,Citation39 and Stanek et al concluded that experience with pharmacogenomic testing may improve the genetics knowledge gap among physicians and drive appropriate clinical uptake.Citation22 Our results are supportive of such suggestions, and further indicate that point-of-care resources that address practical questions about test ordering and interpretation are needed.

Educational resources for practicing physicians

Appropriate integration of pharmacogenomics into the clinical setting depends in part on addressing the identified knowledge gap among physicians using educational resources that will best meet the needs of practicing physicians. Although physicians in our survey named a number of resources that they had consulted, more than half reported that they were not able to get the information they needed or wanted from them. These results are consistent with others reporting that physicians are not completely satisfied with commonly available genomic education resources.Citation39 It is not clear whether survey participants were sufficiently aware of currently available pharmacogenomic resources; answers may have been based on only those resources of which they were aware. Respondents indicated a desire for a “physician-friendly” resource that contains information most pertinent to therapeutic decision making for individual patients: guidance on how to interpret pharmacogenomic test results and recommendations for prescribing based on such results, the effect of genetic variation on drug action, and a listing of laboratories offering pharmacogenomic testing were among the most highly preferred components.

While several resources containing pharmacogenomic information exist, many do not include the type of information that our study participants reported they need or want in an ideal resource. For example, the FDA maintains a list of drugs with labeling that includes mention of pharmacogenomic biomarkers.Citation20 While this is a useful inventory of drugs affected by genetic variation, few drug labels include specific dosage information for patients with certain genotypes or information about how to interpret pharmacogenomic test results. The Indiana University Division of Clinical Pharmacology maintains a table of drugs metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes, including references for associated studies.Citation49 The information is valuable, but is not meant to be a clinical guide for physicians. A notable exception is the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB).Citation50 Over the last few years, the amount of clinical information available on its website has steadily increased, including dosing guidelines, the effect of selected genetic variations on drug action, and information about which laboratories perform the genetic test(s) specific to each drug.Citation24 The PharmGKB database also includes straightforward overviews of the mechanism of drug action, links to drug labeling, references, and genotype-based prescribing guidelines developed by the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. Since this resource seems to include the type of information our study participants reported they want in an ideal resource, yet more than half of participants reported that they were not able to get the information they wanted from current resources, we believe that they may not be aware of PharmGKB or other resources like it that may indeed meet their needs. Efforts to increase awareness of currently available resources should be undertaken, and may partially address the pharmacogenomics knowledge gap.

Electronic resources, such as websites or mobile applications, are clearly preferred by physicians in our study. This is not surprising, since more than three-quarters of participants said they access health care-related information using smartphones and/or computers, a number that appears to be reflective of national trends.Citation51,Citation52 Clinical decision support, ie, educational information integrated into an EMR system and tailored to the clinical situation, has been promoted as a potentially valuable point-of-care resource for pharmacogenomics.Citation10,Citation23,Citation53 For example, if a drug known to cause variable response depending on a patient’s genotype is prescribed, the EMR would alert the prescriber and provide links to more detailed information, including pharmacogenomic testing options; or, if a patient’s genotype is known, alerts are tailored based on which drugs would be subtherapeutic or potentially result in an adverse event for that patient. This type of clinical decision support has been instituted within the EMR systems of several medical centers,Citation26–Citation29,Citation54–Citation56 with early analyses suggesting that it successfully guides appropriate prescribing.Citation57,Citation58

Physicians in our study trust a number of different sources to develop educational resources, with health care-related software companies at the top of the list. Since the survey was delivered through Epocrates, we believe some bias may exist in the choice of a health care-related software company. Another preferred source is a professional/specialty society. Collaboration on the development of pharmacogenomic resources between health care-related software companies and professional/specialty societies, or endorsement of an existing resource, such as PharmGKB or an EMR-integrated clinical decision-support system by a professional/specialty society, may foster trust in the source while increasing awareness and uptake of the resource among members of the professional/specialty society.

As medical home- and team-based care models proliferate, other health professionals may act as pharmacogenomic resources for physicians. For example, a collaboration between pharmacists and physicians has been tested, in which pharmacogenomic testing is initiated at the pharmacy and then the prescribing physician receives the results of the test and is given the opportunity to alter prescription details.Citation59,Citation60 During the study period, prescriptions were altered for approximately half of participating patients.Citation61 Similarly, genetic counselors have been proposed as an integral part of the pharmacogenomic delivery team because of their expertise in risk communication and counseling methodology.Citation62 Genetic counselors may be particularly important when pharmacogenomic testing is undertaken to guide treatment for conditions that are genetic in nature.Citation63 It should be noted that both pharmacists and genetic counselors may have pharmacogenomics knowledge deficits, and that they too require educational resources.Citation62–Citation65

Study limitations

Our study had limitations that should be noted. The survey sample was small, and although the sample appeared to be representative of the sex and geographic location of the physician population, generalizations about the larger physician population should be made cautiously. Younger physicians (aged 25–44 years) were overrepresented in our survey sample; since previous studies have shown that early adopters of genetic technologies tend to be those who have graduated from medical school most recently,Citation22 our study sample may have included more early adopters than the general physician population. Further, since the survey was delivered electronically through Epocrates, our study sample may have been overrepresented by those who are comfortable with technology. Also, the survey participants knew some information about the focus of the study, since the invitation noted that the survey was about genetics in medical practice, and thus may have been more likely than the general physician population to be interested in and familiar with genetics and/or pharmacogenomics.

Conclusion

In this study, we explored the pharmacogenomic knowledge gaps demonstrated by many physicians, and their preferences for educational resources that meet their clinical pharmacogenomic needs. We found that familiarity with pharmacogenomics continues to be low and that knowledge gaps persist, possibly driven by a misunderstanding of what “pharmacogenomics” means. Educational resources tailored to physicians’ needs are desired, with the preferred format being electronic. Resources that are seamlessly integrated into a physician’s daily work routine and are supported or vetted by professional societies seem most likely to contribute to appropriate clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics.

With the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies, the amount of genomic information poised to impact clinical care has vastly increased. Improved outcomes for patients who have undergone pharmacogenomic testing prior to being administered certain medications have been demonstrated,Citation66,Citation67 with more trials under way.Citation68,Citation69 However, mechanisms to prepare physicians for the appropriate use of pharmacogenomic information are urgently needed. The amount of clinical information about pharmacogenomics has become so great and continues to expand so rapidly that physicians cannot possibly learn and develop the necessary skills to apply it from traditional formal training. Information available at the point of care, targeted to the clinical situation at hand, is most likely to be meaningful and to promote improved outcomes for patients. Collaboration among a broad number of stakeholders, such as that being undertaken by the National Human Genome Research Institute’s Intersociety Coordinating Committee, is likely to be most successful in addressing educational resource deficits by reaching a large number of physicians in many specialty areas.Citation70 As a federation organization representing all 50 US state medical societies and more than 100 medical specialty societies, the AMA is particularly suited to act as a convener to promote improved resource development.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank members of the AMA Market Research staff for their assistance in developing and fielding the survey. We also thank Modena Wilson, MD, MPH (AMA) for her helpful comments on the manuscript. The work presented in this paper was supported by the AMA.

Supplementary material

Survey of primary care physicians, cardiologists, and psychiatrists: pharmacogenomics knowledge, use of testing, and need for a pharmacogenomic resource

I. DEMOGRAPHICS

| 1 | In what state do you currently practice medicine? (Fill-in text box) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Please select your gender.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Which of the following ranges contains your age?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | How many years have you been in practice since you completed your residency or fellowship? (Fill-in text box) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | How many hours of direct patient care do you provide during a typical week? (Fill-in text box) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Please indicate which of the following best describes your medical specialty:

If answer to question 6 was not cardiology, family medicine, general medicine, internal medicine, or psychiatry, the survey was terminated at this point. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Which of the following best describes your primary practice setting?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Do you use an electronic medical record (EMR) in your office?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Which, if any, of the following devices do you use to access healthcare-related information? Please select all that apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

II. CURRENT KNOWLEDGE/USAGE OF PHARMACOGENOMICS INFORMATION

How important are each of the following issues when choosing appropriate drug therapy/dosing regimens for your patients?

| 17 | How familiar are you with pharmacogenomics?

Pharmacogenomics is the influence of genetic differences on the human variability in drug response. Please keep this definition in mind as you answer the following questions. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | To what extent do you agree or disagree that you are confident in your knowledge about the influence of genetics on drug therapy?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Have you had any type of formal training in pharmacogenomics?

If answer to question 19 was “Yes”: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19a | In which of the following types of settings have you received formal training in pharmacogenomics? Please select all that apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | Have you ordered a pharmacogenomic test within the last year (2011)?

If answer to question 20 was “Yes”: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20a | What type of pharmacogenomic test(s) have you ordered in the last year (2011)? Please be specific in your response. (Fill-in text box) If answer to question 20 was “No”: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20b | Which of the following issues explain why you haven’t ordered a pharmacogenomic test for a patient in the last year (2011)? Please select all that apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | Do you anticipate ordering a pharmacogenomic test in the next year (2012)?

If answer to question 21 was “Yes”: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21a | What type of pharmacogenomic test(s) do you anticipate ordering in the next year (2012)? Please be specific in your response. (Fill-in text box) If answer to question 21 was “No”: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21b | Which of the following issues explain why you don’t anticipate ordering a pharmacogenomic test in the next year (2012)? Please select all that apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | Which, if any, of the following sources of information do you consult when you have questions about pharmacogenomics? Please select all that apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | Do you feel that there are resources currently available that enable you to access the pharmacogenomics information you need or want to know?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

III. PHARMACOGENOMICS KNOWLEDGE ASSESSMENT

| 24 | To the best of your knowledge, which sections of the drug product labeling could contain pharmacogenomic information? Please select all that apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | How helpful do you find the pharmacogenomics information typically included in drug labeling?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | To the best of your knowledge, which of the following drugs elicit substantially variable population responses due to a patients’ genetic background? Please select all that apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27 | To the best of your knowledge, what is the most commonly recognized mechanism for pharmacogenomic differences in drug response? Is it mutations affecting …?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | Before today, were you aware of the abbreviation “CYP”? If yes, please explain.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | To the best of your knowledge, approximately what percentage of the top 200 prescribed drugs is metabolized by an enzyme subject to pharmacogenomic variation?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IV. CONCEPT OF IDEAL PHARMACOGENOMICS RESOURCE

| 30 | Imagine an ideal resource that could be consulted when you have questions about pharmacogenomics or medications that may have pharmacogenomic properties. What type of content should be included in such a resource? Please select all that apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In which of the following types of formats would you prefer to use an ideal pharmacogenomics resource? Please rank each format by selecting a ‘1’ for your most preferred format, ‘2’ for your second most preferred format, and so on. A rank of ‘5’ represents your least preferred format. Use each number only once.

| 36 | Which of the following would be your preferred source for an ideal pharmacogenomic resource?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- National Newborn Screening and Genetics Resource CenterNational newborn screening status report2013 Available from: http://genes-r-us.uthscsa.edu/sites/genes-r-us/files/nbsdisorders.pdfAccessed March 5, 2014

- AwadaAVandoneAMAftimosPPersonalized management of patients with solid cancers: moving from patient characteristics to tumor biologyCurr Opin Oncol201224329730422410457

- Johansen TaberKADickinsonBDWilsonMThe promise and challenges of next-generation genome sequencing for clinical careJAMA Intern Med2014174227528024217348

- KlitzmanRChungWMarderKAttitudes and practices among internists concerning genetic testingJ Genet Couns20132219010022585186

- HarveyEKFogelCEPeyrotMChristensenKDTerrySFMcInerneyJDProviders’ knowledge of genetics: a survey of 5915 individuals and families with genetic conditionsGenet Med20079525926717505202

- BaarsMJHennemanLTen KateLPDeficiency of knowledge of genetics and genetic tests among general practitioners, gynecologists, and pediatricians: a global problemGenet Med20057960561016301861

- KorfBRFeldmanGWiesnerGLReport of Banbury Summit meeting on training of physicians in medical genetics, October 20–22, 2004Genet Med20057643343816024976

- SutherSGoodsonPBarriers to the provision of genetic services by primary care physicians: a systematic review of the literatureGenet Med200352707612644775

- McInerneyJDEdelmanENissenTReedKScottJAPreparing health professionals for individualized medicinePer Med201295529537

- FeeroWGGreenEDGenomics education for health care professionals in the 21st centuryJAMA2011306998999021900139

- SalariKThe dawning era of personalized medicine exposes a gap in medical educationPLoS Med200968e100013819707267

- ScheunerMTSieverdingPShekellePGDelivery of genomic medicine for common chronic adult diseases: a systematic reviewJAMA2008299111320133418349093

- GuttmacherAEPorteousMEMcInerneyJDEducating health-care professionals about genetics and genomicsNat Rev Genet20078215115717230201

- Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health, and SocietyGenetics Education and TrainingBethesda (MD)Department of Health and Human Services2011 Available from: http://osp.od.nih.gov/sites/default/files/SACGHS_education_report_2011.pdfAccessed March 5, 2014

- HamiltonABOishiSYanoEMGammageCEMarshallNJScheunerMTFactors influencing organizational adoption and implementation of clinical genetic servicesGenet Med201416323824523949572

- TachéSVSönnichsenAAshcroftDMPrevalence of adverse drug events in ambulatory care: a systematic reviewAnn Pharmacother2011457–897798921693697

- LazarouJPomeranzBCoreyPNIncidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studiesJAMA199827915120012059555760

- EvansWEMcLeodHLPharmacogenomics: drug disposition, drug targets and side effectsN Engl J Med2003348653854912571262

- GriceGRSeatonTLWoodlandAMMcLeodHLDefining the opportunity for pharmacogenetic intervention in primary carePharmacogenomics200671616516354125

- US Food and Drug AdministrationTable of pharmacogenomic bio-markers in drug labeling Available from: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htmAccessed March 5, 2014

- FruehFWAmurSMummaneniPPharmacogenomic biomarker information in drug labels approved by the United States food and drug administration: prevalence of related drug usePharmacotherapy200828899299818657016

- StanekEJSandersCLJohansen TaberKAAdoption of phar-macogenomic testing by US physicians: results of a nationwide surveyClin Pharmacol Ther201291345045822278335

- HagaSBBurkeWGinsburgGSMillsRAgansRPrimary care physicians’ knowledge of and experience with pharmacogenetic testingClin Genet201282438839422698141

- McDonaghEMWhirl-CarrilloMGartenYAltmanRBKleinTEFrom pharmacogenomic knowledge acquisition to clinical applications: the PharmGKB as a clinical pharmacogenomic biomarker resourceBiomark Med201125679580622103613

- KuoGMMaJDLeeKCInstitutional Profile: University of California San Diego Pharmacogenomics Education Program (PharmGenEd™): bridging the gap between science and practicePharmacogenomics201112214915321332308

- HicksJKCrewsKRHoffmanJMA clinician-driven automated system for integration of pharmacogenetic interpretations into an electronic medical recordClin Pharmacol Ther201292556356622990750

- PulleyJMDennyJCPetersonJFOperational implementation of prospective genotyping for personalized medicine: the design of the Vanderbilt PREDICT projectClin Pharmacol Ther2012921879522588608

- JohnsonJABurkleyBMLangaeeTYClare-SalzlerMJKleinTEAltmanRBImplementing personalized medicine: development of a cost-effective customized pharmacogenetics genotyping arrayClin Pharmacol Ther201292443743922910441

- O’DonnellPHBushASpitzJThe 1200 patients project: creating a new medical model system for clinical implementation of pharmacogenomicsClin Pharmacol Ther201292444644922929923

- American Medical Association, Critical Path Institute, Arizona Center for Research and Education on TherapeuticsPharmacogenomics: Increasing the Safety and Effectiveness of Drug TherapyChicagoAMA2011 Available from: http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/genetics/pgx-brochure-2011.pdfAccessed March 5, 2013

- American Medical Association, Critical Path Institute, Arizona Center for Research and Education on TherapeuticsPersonalized Health Care Report 2008: Warfarin and Genetic TestingChicagoAMA2008 Available from: http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/genetics/warfarin-brochure.pdfAccessed March 5, 2014

- GeneFacts.orgPharmacogenetics fact sheets Available from: http://genefacts.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=392&Itemid=457Accessed March 5, 2014

- RayTFDA/AMA launch free online course aiming to improve basic PGx literacy2007 Available from: http://www.genomeweb.com/dxpgx/fdaama-launch-free-online-course-aiming-improve-basic-pgx-literacyAccessed March 5, 2014

- JohnsonJPharmacogenetics in clinical practice: how far have we come and where are we going?Pharmacogenomics201314783584323651030

- ManolioTAChisholmRLOzenbergerBImplementing genomic medicine in the clinic: the future is hereGenet Med201315425826723306799

- CrewsKRHicksJKPuiCHRellingMVEvansWEPharmacogenomics and individualized medicine: translating science into practiceClin Pharmacol Ther201292446747522948889

- SchumockGTWaltonSMParkHYFactors that influence prescribing decisionsAnn Pharmacother200438455756214966259

- NutescuEAParkHYWaltonSMFactors that influence prescribing within a therapeutic drug classJ Eval Clin Pract200511435736516011648

- SelkirkCGWeissmanSMAndersonAHulickPJPhysicians’ preparedness for integration of genomic and pharmacogenetic testing into practice within a major healthcare systemGenet Test Mol Biomarkers201317321922523390885

- BonterKDesjardinsCCurrierNPunJAshburyFDPersonalised medicine in Canada: a survey of adoption and practice in oncology, cardiology and family medicineBMJ Open201111e000110

- FargherEAEddyCNewmanWPatients’ and healthcare professionals’ views on pharmacogenetic testing and its future delivery in the NHSPharmacogenomics20078111511151918034616

- BartholowMTop 200 drugs of 2012Pharm Times2013797 Available from: http://www.pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2013/July2013/Top-200-Drugs-of-2012Accessed March 5, 14

- GreenJSO’BrienTJChiappinelliVAHarralsonAFPharmacogenomics instruction in US and Canadian medical schools: implications for per-sonalized medicinePharmacogenomics20101191331134020860470

- GurwitzDLunshofJEDedoussisGPharmacogenomics education: International Society of Pharmacogenomics recommendations for medical, pharmaceutical, and health schools deans of educationPharmacogenomics J20055422122515852053

- KorfBGenetics and genomics education: the next generationGenet Med201113320120221283012

- Howard Hughes Medical Institute, American Association of Medical CollegesScientific Foundations for Future Physicians: Report of the AAMC-HHMI CommitteeWashingtonAAMC2009 Available from: https://www.aamc.org/download/271072/data/scientificfoundationsfor-futurephysicians.pdfAccessed June 16, 2014

- NickolaTJGreenJSHarralsonAFO’BrienTJThe current and future state of pharmacogenomics medical education in the USAPharmacogenomics201213121419142522966890

- KhouryMJCoatesRJEvansJPEvidence-based classification of recommendations on use of genomic tests in clinical practice: dealing with insufficient evidenceGenet Med2010121168068320975567

- Indiana University Division of Clinical PharmacologyP450 drug interaction table Available from: http://medicine.iupui.edu/clinpharm/ddis/main-tableAccessed March 5, 2014

- Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base [website on the Internet] Available from: http://www.pharmgkb.orgAccessed March 5, 2014

- OdzalgaEOdzalgaANeeraAThe smartphone in medicine: a review of current and potential use among physicians and studentsJ Med Internet Res2012145e12823017375

- PutzerGJParkYAre physicians likely to adopt emerging mobile technologies? Attitudes and innovation factors affecting smartphone use in the Southeastern United StatesPerspect Health Inf Manag201291b

- DresslerLGIntegrating personalized genomic medicine into routine clinical care: addressing the social and policy issues of pharmacog-enomic testingNC Med J2013746509513

- PetersonJFBowtonEFieldJRElectronic health record design and implementation for pharmacogenomics: a local perspectiveGenet Med2013151083384124009000

- OverbyCLTarczy-HornochPHoathJIKaletIJVeenstraDLFeasibility of incorporating genomic knowledge into electronic medical records for pharmacogenomic clinical decision supportBMC Bioinformatics201011Suppl 9S1021044357

- TonerBCleveland clinic rolls out EHR-based program to alert docs about PGx tests for azathioprine, abacavir2013 Available from: http://cdnwww.genomeweb.com/clinical-genomics/cleveland-clinic-rolls-out-ehr-based-program-alert-docs-about-pgx-tests-azathiopAccessed March 5, 2014

- BellGCCrewsKRWilkinsonMRDevelopment and use of active clinical decision support for preemptive pharmacogenomicsJ Am Med Inform Assoc201421e1e93e9923978487

- SchildcroutJSDennyJCBowtonEOptimizing drug outcomes through pharmacogenetics: a case for preemptive genotypingClin Pharmacol Ther201292223524222739144

- O’ConnorSKFerreriSPMichaelsNMExploratory planning and implementation of a pilot pharmacogenetic program in a community pharmacyPharmacogenomics201213895596222676199

- TeagardenRJStanekEJOn pharmacogenomics in pharmacy benefit managementPharmacotherapy201232210311122392418

- FerreriSPGrecoAJMichaelsNMImplementation of a phar-macogenomics service in a community pharmacyJ Am Pharm Assoc (2003)201454217218024632932

- MillsRHagaSBClinical delivery of pharmacogenetic testing services: a proposed partnership between genetic counselors and pharmacistsPharmacogenomics201314895796823746189

- CallardANewmanWPayneKDelivering a pharmacogenetic service: is there a role for genetic counselors?J Genet Couns201221452753522052043

- McCulloughKBFormeaCMBergKDAssessment of the pharmacogenomics educational needs of pharmacistsAm J Pharm Educ20117535121655405

- KuoGMLeeKCMaJDImplementation and outcomes of a live continuing education program on pharmacogenomicsPharmacogenomics201314888589523746183

- EpsteinRSMoyerTPAubertREWarfarin genotyping reduces hospitalization rates results from the MM-WES (Medco-Mayo Warfarin Effectiveness Study)J Am Coll Cardiol201055252804281220381283

- MallalSPhillipsECarosiGHLA-B*5701 screening for hypersensitivity to abacavirN Engl J Med2008358656857918256392

- KimmelSEFrenchBAndersonJLRationale and design of the Clarification of Optimal Anticoagulation through Genetics trialAm Heart J2013166343544124016491

- van SchieRMWadeliusMIKamaliFGenotype-guided dosing of coumarin derivatives: the European pharmacogenetics of anticoagulant therapy (EU-PACT) trial designPharmacogenomics200910101687169519842940

- ManolioTAMurrayMFThe growing role of professional societies in educating clinicians in genomicsGenet Med Epub262014