Abstract

Background

Among many possible variables that can be associated with gratitude, researchers list personality traits. Considering that these relationships are not always consistent, the first purpose of the present study was to verify how the Big Five factors connect to dispositional gratitude in a sample of Polish participants. The second purpose was to assess the unique contribution of personality traits on gratitude with multiple regression analyses. Moreover, because much remains to be learned about whether these associations are indirectly influenced by different personal or social variables, the third goal was to explore the role of emotional intelligence as a potential mediational mechanism implicated in the relationship between personality traits and gratitude.

Participants, Methods and Data Collection

The sample consisted of 712 Polish respondents who were aged between 17 and 88. Most of them were women (64.3%). They answered questionnaires concerning their personality traits, emotional intelligence, and gratitude. The research was conducted using the paper-and-pencil method through convenience sampling.

Results

The results showed that both gratitude and emotional intelligence correlated positively and significantly with extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Gratitude and emotional intelligence correlated negatively and significantly with neuroticism. The personality predictor of gratitude with the highest and positive standardized regression value was agreeableness, followed by openness to experience and extraversion. Neuroticism had a negative impact on gratitude. Conscientiousness was the only statistically insignificant predictor in the tested multiple regression model. Moreover, emotional intelligence mediated the relationship between four dimensions of personality (extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and gratitude and acted as a suppressor between neuroticism and gratitude.

Conclusion

The current study broadens our comprehension of the interaction among personality traits, emotional intelligence, and a grateful disposition. Moreover, it imparts a noteworthy foundation not only for the mediatory role of emotional intelligence between four dimensions of personality and gratitude but also for its suppressor effect between neuroticism and being grateful.

Introduction

Throughout history, philosophers and theologians have counted gratitude as an important human virtue.Citation1,Citation2 Moreover, the concept of gratitude has been highly respected in most cultures and religions.Citation3–Citation5 Yet, it has been considered one of the most neglected and undervalued emotions by psychology,Citation6,Citation7 and it has only recently become a significant topic within the field of gratitude research.Citation2,Citation8

Although, there is a lack of concurrence about the nature of the constructCitation5,Citation7 and gratitude has been described in different ways, it has been prevalently conceptualized as a general dispositionCitation9 or a temporary emotional state.Citation10 According to the first perspective, gratitude is defined as a generalized predisposition to acknowledge and answer with appreciation to others’ benevolence (person, God, luck, fate or nature).Citation11 In the second sense, gratitude has been depicted as a complex emotion which follows a costly, unexpected, and intentionally given benefit.Citation12,Citation13 It is elicited from specific situations or reflections.Citation5 In the present study, gratitude is considered as a disposition that refers to a generalized tendency to experience gratitude in daily life.Citation11

Despite the growing interest in gratitude research,Citation2 much remains to be learned about how being grateful is directly related to other personality traits outside of the Western context, and whether these relationships are indirectly influenced by different personal or social variables. Among the various potential models of directionality that link gratitude to numerous components of human functioning, the reverse model and the mediational approach seem quite promising. Consistent with the reverse model, some variables may lead to gratitude. For example, Wood and colleagues examined social support as a factor that may induce gratitude.Citation14 In other studies, intrinsic religiosity/spirituality,Citation11,Citation15,Citation16 appreciation of simple pleasures and natural beautyCitation17 enhanced gratitude. Following this line of reasoning, we assumed that emotional intelligence could lead to gratitude since it is a psychological resource that allows one to perceive, be aware of and better understand others’ and one’s own emotions and behaviors.Citation18 Moreover, emotional intelligence is considered to foster trust,Citation19 contributes to positive relationships with others thanks to interpersonal (social) and intrapersonal (self) dimensions,Citation20 and is related to positive emotional states,Citation21 and gratitude.Citation22 The mediational model suggests the presence of a potential intervening mechanism through which these variables may affect gratitude. In this sense, emotional intelligence was assumed to be a mediator that explains why personality traits may result in a grateful disposition.

Several psychologists imply that both personal and environmental factors may be implicated in the development of gratitude. It has been noted that social functioning, cooperation and reciprocal altruism correlated more strongly with gratitude.Citation4 It also seems that success,Citation23 social support,Citation14 religiosityCitation4 and prayer,Citation24 humility,Citation25 behavioral routines, and social interactionsCitation26 may lead to gratitude. Finally, various studies have showed that gratitude is associated with a positive outlook toward lifeCitation27 and represents an essential positive personality trait.Citation28

Among the many possible variables that can be associated with gratitude, researchers list personality traits. In fact, a review of the literature shows that the relations between the Big Five personality traits and gratitude have already been robustly established. However, considering that these relationships are not always consistent, especially in regard to openness to experience and neuroticism,Citation29 and that there is a lack of similar studies in Poland, the first purpose of the present study was to verify how the Big Five factors connect to dispositional gratitude in a sample of Polish participants. Based on the results of previous analyses performed prevalently in Western countries, it has been assumed (Hypothesis 1) that a significant proportion of the people who are more agreeable,Citation7,Citation11,Citation27 extraverted,Citation11,Citation30–Citation32 conscientious,Citation11,Citation27 open,Citation11,Citation27 and less neuroticCitation11,Citation27 would tend to be more grateful. Positive correlations result from common features combining gratitude with individual personality traits. For example, agreeableness refers to interpersonal trust, harmony-seeking,Citation33 and prosociality. Therefore, since highly agreeable individuals are inclined to display a higher level of social interaction and be more empathetic and liked by others, they may also reveal stronger gratitude and see the goodness of others around them. Extraversion is another trait positively correlating with gratitude. In this regard, WatkinsCitation15 observed that people high in extraversion were warm and sensitive to reward, and thus could be more prompt to reply with gratitude. Regarding openness to experience, which involves receptivity to novel ideas,Citation34 the outcomes of different studies are inconsistent. Saucier and GoldbergCitation30 observed that people who rated themselves as open expressed lower gratitude. McCullough and colleaguesCitation11 found a positive correlation between both variables. In contrast, Watkins et alCitation29 and Breen et alCitation35 reported a lack of correlation between openness and gratitude. Conscientiousness involves, apart from other important features, the propensity to pursue socially recommended rulesCitation36 and to consistently fulfil duties toward other people.Citation37 In accordance with this view, we expected that conscientiousness would be positively associated with gratitude since being grateful results from an awareness of prosocial norms.Citation38 In the case of neuroticism, we assumed that it would be inversely related to gratitude.Citation27,Citation31,Citation36 Since individuals who are high in neuroticism often feel personally inadequate and insecure, they can express doubts within the context of receiving good things from others and, accordingly, show lower gratitude toward them. However, not all studies show such a relationship. For example, NetoCitation39 and Chen et alCitation40 found that neuroticism was not associated with gratitude.

In addition to the first aim (Hypothesis 1), which is replicative of earlier Western correlational research on personality traits and gratitude, the second purpose was to assess the unique contribution of personality traits on gratitude with multiple regression analyses (Hypothesis 2). In fact, McCullough and colleaguesCitation11 consistently observed independent effects of agreeableness and neuroticism on dispositional gratitude across three studies. Applying multiple regression with gratitude as the dependent variable seems to be an important approach since relatively few researchers have considered gratitude as a dependent variable in their analyses.Citation41–Citation43

Moreover, there are some grounds to believe that gratitude may not only be an outcome variable within the reverse model, but a direct relationship between personality traits and being grateful can be accounted for by third variables.Citation14,Citation27 Therefore, the next purpose of the study was to explore a potential mediational mechanism implicated in this association. Our choice was emotional intelligence, which consists in

the capacity to process emotional information accurately and efficiently, including that information relevant to the recognition, construction, and regulation of emotion in oneself. (p. 197)Citation44

A review of the literature shows that emotional intelligence can be conceptualized as a trait and as an ability.Citation45 In our study, we assessed trait emotional intelligence which refers to the self-perception of typical emotion-related dispositions. So understood, it appears to be an important mediating factor since it promotes well-being outcomes,Citation46 optimism and hope.Citation47 Therefore, we assumed that emotional intelligence could be a potential mediator between dimensions of personality according to the Big Five Model, and gratitude (Hypothesis 3). Although there are well-established dilemmas with the implementation of cross-sectional mediation analyses to gather evidence for causal processes,Citation48,Citation49 mediation models are useful with strong prior theoretical justification and empirical supportCitation50 for the relationships between the independent variables, dependent variable, and mediator. In the following section, we have attempted to provide the main rationale that regards the crucial assumption of the temporal precedence in the mediational scheme.Citation51

The first important link in the prospective mediatory relationship is the association between a range of personality traits and emotional intelligence. On a conceptual foundation, McCraeCitation52 called attention to connections between emotional intelligence and facets of the dimensions of the Big Five Model. Moreover, there have been some studies that showed that both constructs are most likely intertwined.Citation53–Citation55 It has been found that emotional intelligence negatively and significantly correlates with neuroticism, and positively and significantly associates with extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.Citation47,Citation56–Citation61 In many of these studies,Citation58,Citation62,Citation63 it has been documented that while neuroticism and extraversion were the strongest personality determinants of emotional intelligence, agreeableness and openness were similarly weak. In turn, Van der Zee et alCitation64 and De RaadCitation65 found that conscientiousness was not linked to emotional intelligence, and Atta et alCitation66 observed conscientiousness as the strongest correlate of emotional intelligence. On the level of multiple regression, Petrides et alCitation67 observed that all Big Five factors of personality contribute significantly to the prediction of emotional intelligence.

The second crucial bond in the mediatory association is the tie between emotional intelligence and gratitude. Although only a small number of studies have examined this connection,Citation68 there is some evidence that both variables are positively correlated.Citation29,Citation69,Citation70 According to WatkinsCitation29 and Ludovino,Citation71 emotional intelligence can be essential for grateful responding since being able to manifest gratitude is a part of having emotional intelligence. Perceiving and valuing positive aspects in the world that characterize gratitudeCitation22 are possible thanks to skills which derive from emotional intelligence, such as establishing interpersonal relationships and maintaining their quality.Citation72 This directional pattern seems to have its solid grounding in some findingsCitation73 that show emotional intelligence as an important predictor of life outcomes. Moreover, emotional intelligence may be a key factor in understanding and processing emotional information accurately and efficiently.Citation74

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 712 participants recruited from Poland, aged 17 to 88 (M = 38.25; SD = 17.94). Most were women (n = 458, 64.3%). The respondents were different in terms of their declared level of education—from primary (34.4%), through technical (7.4%), secondary (27.5%) and higher (30.6%). In addition, 126 participants were residents of villages and towns (17.7%), 215 of small to medium cities up to a population of 50,000 (30.2%), and 371 were residents of large cities of over 50,000 people (52.1%). Most of the respondents assessed their financial conditions as medium (44.7%) and high (45.6%).

Data Collection

The data were collected using a battery of questionnaires via paper-and-pencil mode. A convenience sampling strategy was applied to recruit participants through high schools, colleges, University of the Third Age, as well as through relatives and friends. All of the respondents were informed about the objective of the research and the confidentiality protection policy. Those who agreed to engage in the study were provided with general information about its goal and gave informed consent. Only after showing their agreement, the participants were asked to complete the questionnaires. In the case of adolescents, they could take part in the study only after obtaining written consent from their parents or legal guardians. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology at the University of Szczecin and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurement

The NEO Five-Factor Inventory,Citation75 in the Polish version adapted by Zawadzki et alCitation76 was used to measure five basic domains of individual differences in personality: 1) neuroticism, which refers to the propensity to experience negative emotions, anxiety, apprehensiveness, and psychological distress in response to threats, frustration, and different stressors;Citation77 2) extraversion, which represents the tendency to enjoy social situations and interpersonal relationships;Citation78 3) openness to experience, which reflects the tolerance of ambiguity, curiosity, innovation and imagination;Citation52 4) agreeableness, which denotes the quality of interaction “along a continuum from compassion to antagonism” (p. 888),Citation79 having facets of trust, straightforwardness and altruism; and 5) conscientiousness, which implies both proactive and inhibitive aspects, such as competence, striving to achieve, scrupulosity and cautiousness.Citation79 This tool was created on the basis of the five-factor Big Five Model. It is used to measure personality traits on a 5-point Likert-type scale where 1 means strongly disagree and 5 means strongly agree. Respondents answer 60 statements (12 items per domain). The higher the score on a particular scale, the stronger the intensification of the feature. The reliability of the questionnaire in the current study was adequate: neuroticism (α = 0.82), extraversion (α = 0.77), openness to experience (α = 0.59), agreeableness (α = 0.72) and conscientiousness (α = 0.83).

The Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (INTE),Citation72 based on the model developed by Mayer and Salovey,Citation44 and adapted into Polish by Jaworowska and Matczak,Citation80 measures general emotional intelligence as the ability to recognize emotions, regulate them and use them in solving problems.Citation81 The questionnaire consists of 33 items. Respondents use a 5-point scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree to indicate to what extent each item exemplifies their agreement. The higher the score obtained, the higher the level of emotional intelligence. The internal consistency in the original studies showed an alpha of 0.90. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient was 0.88.

The Gratitude Questionnaire – Six Item Form (GQ-6), developed by McCullough and colleagues,Citation11 and adapted into Polish by Kossakowska and Kwiatek,Citation82 evaluates individual differences in the propensity to experience gratitude in daily life. It is a six-item measure where respondents indicate their responses on a 7-point scale where 1 means strongly disagree and 7 means strongly agree. A higher score means a higher level of gratitude. The reliability of the questionnaire in our study was equal to α = 0.78.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics software, AMOS with Maximum Likelihood Estimation, version 25.0 and the PROCESS 3.2 macro for empirical verification of the created mediation models ().

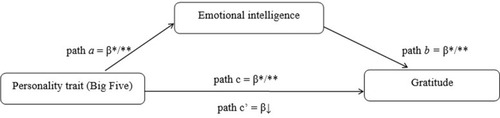

Figure 1 Theoretical model of the role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and gratitude. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

All models were estimated using the bootstrapping method with random sampling with a replacement of 5000 samples with a 95% confidence interval. The minimum value of the significance factor was p < 0.05. In all of the five mediation models created, each of the Big Five personality traits was an independent variable relative to the dependent variable of gratitude and emotional intelligence as the mediator ().

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Initial Analysis

Despite the fact that the bootstrapping method used is resistant to the lack of a normal distribution of the analyzed variables,Citation83 the obtained skewness and kurtosis values were in the range of −1 to 1,Citation84 which indicates that all variables did not differ significantly from the normal distribution ().

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of Analyzed Variables (N = 712)

Multicollinearity, Confounding, and Correlations

Before proceeding to the main analysis, the data were investigated in terms of the occurrence of influential points and outliers using the Mahalanobis distance (with χ2 p < 0.001), Cook’s distance, and leverage values. The criterion for rejecting a given observation was exceeding two of the three indicators used. The assumption about the lack of a lag 1 autocorrelation using the Durbin-Watson test (1 > d > 3) and the lack of a strong correlation of variables using the values of Pearson’s correlation coefficients () and variance inflation factor (VIF < 10) were fulfilled. In addition, the criteria of homogeneity of variance and homoscedasticity were fulfilled.

Table 2 Correlations Between Dimensions of NEO FFI, INTE, and GQ-6 (N = 712)

According to the statistics, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness correlated positively with gratitude. Inversely, neuroticism was associated negatively with gratitude. Such correlational links confirmed Hypothesis 1. Moreover, the same pattern of results was obtained in the case of personality traits and emotional intelligence.

Regression Analysis

To examine the direct effects of the Big Five personality traits as predictors of gratitude (Hypothesis 2), multiple regression analysis using the structural equation model (SEM) was performed. The analysis was conducted with the maximum likelihood method of estimation ().

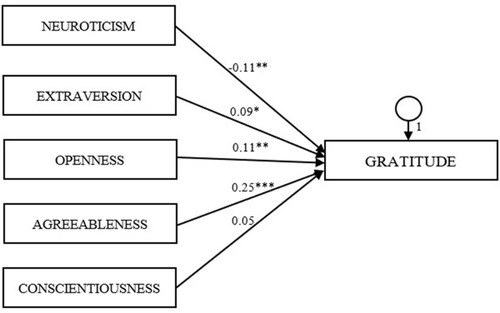

Figure 2 Standardized regression weights in multiple regression structural equation model of Big Five personality traits as predictors of gratitude. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

The results indicate that the personality predictor of gratitude with the highest and positive standardized regression value was agreeableness (β = 0.25; p < 0.001), followed by openness to experience (β = 0.11; p < 0.01) and extraversion (β = 0.09; p < 0.05). Neuroticism had a negative impact on gratitude with β = −0.11 (p < 0.01). Conscientiousness was the only statistically insignificant predictor in the tested multiple regression model (β = 0.05; p > 0.05). The Big Five variables explained 13% of the variance in gratitude, R2(4, 711) = 0.13, p < 0.05.

Mediation Analysis

The results of the mediation analysis showed statistically significant values for each of the created models (). All linear models fit the data well, as evidenced by statistically significant (p < 0.001) F values. In addition, each personality trait as an independent variable explained from 9% to 12% of the variance of the dependent variable.

Table 3 Results of Mediation Analysis with Unstandardized Regression Coefficients (N = 712)

The negative indirect effect value in model A (Indirect = −0.60; 95% CI[−0.84; −0.39]) may be a result of cooperative suppressionCitation85 of emotional intelligence for the relationship of neuroticism and gratitude. For the remaining models, emotional intelligence proved to be an important mediator for gratitude as a dependent variable and the independent variable: extraversion (Indirect = 1.35; 95% CI[0.96;1.77]), openness to experience (Indirect = 0.84; 95% CI[0.53;1.19]), agreeableness (Indirect = 0.72; 95% CI[0.45;1.03]) and conscientiousness (Indirect = 1.15; 95% CI[0.83;1.50]). Statistically insignificant values of the unstandardized regression coefficients of the c’ path in model B (B = 0.41; p < 0.05), model C (B = 0.60; p < 0.05) and model E (B = 0.33; p < 0.05) testify to full mediation models,Citation86 while model D is an example of partial mediation for which the regression value after adding a mediator decreased from B = 3.30 (p < 0.001) to B = 2.58 (p < 0.001). Therefore, the statistics obtained in the present study confirmed Hypothesis 3, showing that emotional intelligence was a mediator between four personality factors (extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, conscientiousness) and gratitude. Moreover, emotional intelligence acted as a suppressor in the relationship between neuroticism and gratitude.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was threefold. The first goal was to verify whether there is an association between dimensions of personality and gratitude within the Polish context. The second aim was to assess the unique contribution of personality traits on gratitude with multiple regression analyses. The third goal was to estimate the mediatory role of emotional intelligence on the association between personality traits and a grateful disposition.

With respect to the first goal, our results are consistent with other previous studiesCitation87 and demonstrate the cross-cultural consistency of the relation between personality traits and gratitude. Starting with a negative correlation between neuroticism and gratitude, there is some evidence that being grateful is related to lower anxiety,Citation9,Citation11, Citation88 depression,Citation9 negative emotions,Citation11 and post-traumatic stress disorder.Citation89,Citation90 LinCitation28 found that those who were more grateful were also more inclined to feel shame and anger less frequently than less grateful individuals. All of the abovementioned correlates of gratitude are listed by different researchers as components of neuroticism. Therefore, a feeling of being thankful and appreciative is related to a lower predisposition to experience negative affects and psychological distress. In other words, people who are anxious may express higher levels of distrust about others’ motives which consequently may lead to lower gratitude. Regarding the positive correlation between extraversion and gratitude, our outcomes reflect those findings obtained by other authors, as well. For example Wood and colleaguesCitation7,Citation27 reported that warmth, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity, excitement-seeking, and positive emotions were positively associated with gratitude. In other studies,Citation40 gratitude correlated modestly with extraversion, suggesting that being grateful comes with enthusiasm and optimism. Extraverted people may attribute received benefits in the benefactor’s intentions with more confidence thus expressing their gratitude. Although in some other reports, openness to experience did not correlate with gratitude,Citation29,Citation35 or was associated negatively,Citation30 our findings are in line with the results found by McCullough and colleagues,Citation11 and Wood.Citation14,Citation27 WatkinsCitation29 found a convincing explanation for this variety of results. It seems that the more cognitive facets of openness may be either unrelated or even negatively associated with gratitude. In contrast, the more emotional features of openness may show positive links with gratitude. Thus, it can be assumed that the emotional aspects of openness to experience prevailed in our sample. In terms of agreeableness, the positive correlation with gratitude was the strongest among the other Big Five dimensions. This is understandable if we consider that highly agreeable individuals enjoy more positive interpersonal relationships than their less agreeable counterparts. In fact, empirical dataCitation35 suggest that gratitude is an interpersonal strength that consists in empathy and adaptive social behaviors. Therefore, agreeableness and gratitude share common characteristics, this is, pursuing positive actions toward other people.Citation28 Finally, conscientiousness was positively associated with gratitude, as well. Such a result is not surprising if we consider that conscientiousness, among other different features, consists in following socially prescribed social norms.Citation90 Similarly, some studies have showed that being grateful increases the motivation to behave according to communal,Citation91 cultural,Citation92 and socialCitation93 norms.

With regard to the second aim, the current study assessed that four of five personality traits predicted unique variance in the grateful disposition, thus not only replicating the results obtained by McCullough et al,Citation11 but providing more information about the role of the remaining personality dimensions, as well. In fact, the present outcomes suggest that in addition to the agreeableness and neuroticism found by the abovementioned authors, extraversion and openness to experience also predicted gratitude. Hence, it may be assumed that persons who are kind and responsive to others (higher agreeableness), experience awe and a broader range of positive emotions in view of goodness and beauty (higher openness to experience), are less tense or anxious (lower neuroticism) and are more sensitive to reward, tend to recognize and respond gratefully to the benevolence of others. These results can be justified on a theoretical basis as reported by McCullough and collaborators (2001)Citation8 who claim that people with stronger personality dispositions toward prosocial behavior are more likely to appreciate others’ benevolence and express their gratitude than individuals with a weaker prosocial approach. In fact, all of the Big Five predictors of gratitude (except neuroticism), identified in the present study, share a common characteristic of increased positive attitudes toward others. For example, McAdamsCitation94 observes that extraverts tend to search for social relationships. Consequently, they enhance their opportunity of getting assistance and acts of benevolence from others which, in turn, can lead to higher gratitude. The opposite can be expected in the case of individuals high in the trait of neuroticism who, because of anxiety and shyness, avoid social interactions and, thus, are less exposed to situations of kindness and express lower levels of gratitude. Similarly, openness to experience together with agreeableness are considered conceptually and empirically associated with prosocial behavior.Citation95 The existing literatureCitation96,Citation97 suggests that open and agreeable people are interpersonally trusting and susceptible to a view of positive outcomes in life. Since gratitude is a prosocial trait itselfCitation98 which is felt in the context of receiving good things, it is therefore reasonable that it correlates with other prosocial traits.Citation99

With respect to the third goal, emotional intelligence acted as a mediator in the association between four personality traits (extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness) and a grateful disposition. These outcomes confirm some theoretical insights and empirical evidence presented by researchers who have posited that emotional intelligence contributes to establishing and maintaining interpersonal relationships.Citation72 For example, Bar-OnCitation100 suggested that individuals who display emotional intelligence effectively understand and express themselves. Moreover, they also have the ability to understand the feelings of other people and use this knowledge to relate to them. Therefore, on the basis of the present research, it can be cautiously assumed that four broad domains of personality (extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness) can lead to higher gratitude when people experience empathy, have the capacity to self-monitor in social situations, and understand others’ emotions and behaviors.

Moreover, emotional intelligence also acted as a suppressor in the relationship between neuroticism and gratitude. The outcome found in this study may suggest that the ability to regulate emotions in the self may impact the increase of gratitude in people with a tendency to higher levels of anxiety and fear. Therefore, it may be carefully presumed that neuroticism does not entirely preclude the feelings of gratitude if individuals with anxiety try to develop skills specific to emotional intelligence. In fact, independently of personality traits, abilities associated to emotional intelligence can be learned.Citation101 In this respect, our result has educational and therapeutic implications, denoting that those persons who demonstrate stronger traits of neuroticism, and self-consciousness, as one of its facets, may show certain levels of gratitude if they manage to observe and analyze their emotions and use their self-awareness as a resource.

Limitations

Despite the significance of these results, we should address several limitations. First, although the outcomes confirmed the suggested mediatory model, the cross-sectional character of the data, with no temporal inquiry, does not allow any inferences on causal and predictive impact. We acknowledge that future research and different study design alternatives should be considered and employed before these mediation models can be confirmed. More specifically, longitudinal and experimental approaches would furnish a more accurate clarification of the relationships tested. Second, gaining significant statistical effects from mediation analyses does not denote that we have proof to assert that emotional intelligence is a mediator in the relationship between personality traits and gratitude. Indeed, greater emotional intelligence could be a result of gratitude. Therefore, in future analyses, researchers should consider an alternative causal model or different mediator possibilities.Citation49 Moreover, expressing gratitude may actually be one component of emotional intelligence, which means that it is part of the same latent variable and could not act as a mediator. Similarly, both gratitude and emotional intelligence could be interstitial personality traits, meaning that they represent the interplay of personality factors.Citation102 However, taking into account that in the social sciences, different variables may act in a “cycle of virtue”,Citation15 we can expect that emotional intelligence enhances gratitude and gratitude enhances emotional intelligence, as well. Their relationship may consist in an upward spiral where both variables may coexist in reciprocal exchange. Third, the data were gathered through the use of self-report methods that might enhance desirability bias and alter the soundness of the results. Hence, a guarded interpretation is recommended when using the findings. In future investigations, it would be helpful to implement a social desirability scale with the goal of preventing or decreasing such a bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, from a theoretical point of view, the current study broadens our comprehension of the interaction among personality traits, emotional intelligence, and a grateful disposition. It imparts a noteworthy foundation not only for the mediatory role of emotional intelligence between four dimensions of personality and gratitude, but also for its suppressor effect between neuroticism and being grateful, as well. More precisely, it is possible to consider that emotionally intelligent people who display trust, experience positive emotions, are open to new experiences, show propensity to follow socially accepted norms, and manage doubts and negative affect may demonstrate higher levels of gratitude. In supporting this perspective, the mediation effect of emotional intelligence was found in the relationship between personal traits and optimism/hope,Citation47 and between need for relatedness and flourishing/happiness.Citation101 From a practical point of view, the development of emotional intelligence skills can provide people with accurate acknowledgment and appreciation of others’ generosity.

Data Sharing Statement

The data sets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the study participants.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Emmons RA. An introduction In: Emmons RA, McCullough ME, editors. The Psychology of Gratitude. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004:3‒16.

- Rusk RD, Vella-Brodrick AV, Waters L. Gratitude or gratefulness? A conceptual review and proposal of the system of appreciative functioning. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17(5):2191‒2212. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9675-z

- Armenta CN, Fritz MM, Lyubomirsky S. Functions of positive emotions: gratitude as a motivator of self-improvement and positive change. Emot Rev. 2016;9(3):183‒190. doi:10.1177/1754073916669596

- Aghababaei N, Błachnio A, Aminikhoo M. The relations of gratitude to religiosity, well-being, and personality. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2018;21(4):408‒417. doi:10.1080/13674676.2018.1504904

- Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(2):377‒389. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

- Solomon RC. Foreword In: Emmons RA, McCullough ME, editors. The Psychology of Gratitude. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004:v‒xii.

- Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AWA. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(7):890‒905. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005

- McCullough ME, Kilpatrick SD, Emmons RA, Larson DB. Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychol Bull. 2001;127(2):249‒266. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.127.2.249

- Petrocchi N, Couyoumdjian A. The impact of gratitude on depression and anxiety: the mediating role of criticizing, attacking, and reassuring the self. Self Identity. 2016;15(2):191‒205. doi:10.1080/15298868.2015.1095794

- Allemand M, Hill PL. Gratitude from early adulthood to old age. J Pers. 2014;84(1):21‒35. doi:10.1111/jopy.12134

- McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;82(1):12‒127. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112

- Forster DE, Pedersen EJ, Smith A, McCullough ME, Lieberman D. Benefit valuation predicts gratitude. Evol Hum Behav. 2017;38(1):18‒26. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.06.003

- Froh JJ, Bono G, Emmons R. Being grateful is beyond good manners: gratitude and motivation to contribute to society among early adolescents. Motiv Emot. 2010;34(2):144‒157. doi:10.1007/s11031-010-9163-z

- Wood AM, Maltby J, Gillett R, Linley PA, Joseph S. The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: two longitudinal studies. J Res Pers. 2008;42(4):854‒871. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.003

- Watkins PC, Woodward K, Stone T, Kolts RL. Gratitude and happiness: development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Soc Behav Pers. 2003;31(5):431‒452. doi:10.2224/sbp.2003.31.5.431

- Emmons RA, Kneezel TT. Giving thanks: spiritual and religious correlates of gratitude. J Psychol Christ. 2005;24(2):140‒148.

- Watkins PC, Van Gelder M, Frias A. Furthering the science of gratitude In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009:437‒445.

- Boyatzis RE. The behavioral level of emotional intelligence and its measurement. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1438. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.0143830150958

- Knight JR, Bush HM, Mase WA, Riddell MC, Liu M, Holsinger JW. The impact of emotional intelligence on conditions of trust among leaders at the Kentucky department for public health. Front Public Health. 2015;3:33. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2015.0003325821778

- Di Fabio A, Kenny ME. Promoting well-being: the contribution of emotional intelligence. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1182. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.0118227582713

- Carvalho VS, Guerrero E, Chambel MJ. Emotional intelligence and health students’ well-being: a two-wave study with students of medicine, physiotherapy and nursing. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;63(1):35‒44. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.010

- Shi M, Du T. Associations of emotional intelligence and gratitude with empathy in medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):116. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02041-432303212

- Fredrickson BL. Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds In: Emmons RA, McCullough ME, editors. The Psychology of Gratitude. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004:145‒166.

- Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Braithwaite SR, Graham SM, Beach SR. Can prayer increase gratitude? Psycholog Relig Spiritual. 2009;1(3):139‒149. doi:10.1037/a0016731

- Kruse E, Chancellor J, Ruberton PM, Lyubomirsky S. An upward spiral between gratitude and humility. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2014;5(7):805‒814. doi:10.1177/1948550614534700

- Naito T, Washizu N. Gratitude in life-span development: an overview of comparative studies between different age groups. J Behav Sci. 2019;14(2):80‒93.

- Wood AM, Joseph S, Maltby J. Gratitude predicts psychological well-being above the big five facets. Pers Individ Differ. 2009;46(4):443‒447. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.11.012

- Lin CC, Yeh YC. A higher-order gratitude uniquely predicts subjective well-being: incremental validity above the personality and a single gratitude. Soc Indic Res. 2014;119(2):909‒924. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0518-1

- Watkins PC. Gratitude and the Good Life. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media; 2014.

- Saucier G, Goldberg LR. What is beyond the big five? J Pers. 1998;66:495‒524. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00022

- McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. Gratitude in intermediate affective terrain: links of grateful moods to individual differences and daily emotional experience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;86(2):295‒309. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.295

- Schueller SM. Personality fit and positive interventions: extraverted and introverted individuals benefit from different happiness increasing strategies. Psychol. 2012;3(12A):1166‒1173. doi:10.4236/psych.2012.312A172

- Brislin RW, Lo KD. Culture, personality, and people’s uses of time: key interrelationships In: Hersen M, Thomas JC, editors. Comprehensive Handbook of Personality and Psychopathology. New Jersey, NY: Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006:44‒64.

- Peterson C, Seligman MEP. Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004.

- Breen WE, Kashdan TB, Lenser ML, Fincham FD. Gratitude and forgiveness: convergence and divergence on self-report and informant ratings. Pers Individ Differ. 2010;49(8):932‒937. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.07.033

- Roberts BW, Jackson JJ, Fayard JV, Edmonds G, Meints J. Conscientiousness In: Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editors. Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior. New York, NY: The Guliford Press; 2009:369‒381.

- Eisenberg N, Duckworth AL, Spinrad TL, Valiente C. Conscientiousness: origins in childhood? Dev Psychol. 2014;50(5):1331‒1349. doi:10.1037/a0030977

- Bartlett MY, DeSteno D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior. helping when it costs you. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(4):319‒325. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x

- Neto F. Forgiveness, personality and gratitude. Pers Individ Differ. 2007;43(8):2313‒2323. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.07.010

- Chen LH, Chen MY, Kee YH, Tsai YM. Validation of the gratitude questionnaire (GQ) in Taiwanese undergraduate students. J Happiness Stud. 2009;10(6):655‒664. doi:10.1007/s10902-008-9112-7

- Krause N. Religious involvement, gratitude, and change in depressive symptoms over time. Int J Psychol Relig. 2009;19(3):155‒172. doi:10.1080/10508610902880204

- Amini S, Namdari K, Kooshki HM. The effectiveness of positive psychotherapy on happiness and gratitude of female students. Int J Educ Psychol Res. 2016;2(3):163‒169.

- Bono G, Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Gratitude in practice and the practice of gratitude In: Linley PA, Joseph S, editors. Positive Psychology in Practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Waley & Sons; 2004:464‒481.

- Mayer JD, Salovey P. Emotional intelligence and the construction and regulation of feelings. Appl Prev Psychol. 1995;4(3):197‒208. doi:10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80058-7

- O’Connor PJ, Hill A, Kaya M, Martin B. The measurement of emotional intelligence: a critical review of the literature and recommendations for researchers and practitioners. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1116. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.0111631191383

- Bhullar N, Schutte NS, Malouff JM. The nature of well-being: the roles of hedonic and eudaimonic processes and trait emotional intelligence. J Psychol. 2013;147(1):1‒16. doi:10.1080/00223980.2012.667016

- Di Fabio A, Palazzeschi L, Bucci O, Guazzini A, Burgassi C, Pesce E. Personality traits and positive resources of workers for sustainable development: is emotional intelligence a mediator for optimism and hope? Sustainability. 2018;10(10):3422. doi:10.3390/su10103422

- Fiedler K, Schott M, Meiser T. What mediation analysis can (not) do. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2011;47(6):1231‒1236. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.007

- Fiedler K, Harris C, Schott M. Unwarranted inferences from statistical mediation tests – an analysis of articles published in 2015. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2018;75:95‒102. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2017.11.008

- Figueredo AJ, Garcia RA, Cabeza de Baca T, Gable JC, Weise D. Revisiting mediation in the social and behavioral sciences. J Methods Meas Soc Sci. 2013;4(1):1‒19. doi:10.2458/v4i1.17761

- Winer ES, Cervone D, Bryant J, McKinney C, Liu RT, Nadorff MR. Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: atemporal associations do not imply causation. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72(9):947‒955. doi:10.1002/jclp.22298

- McCrae RR. Emotional intelligence from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality In: Bar-On R, Parker JDA, editors. The Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. New York, NY: Jossey-Bass; 2000:263‒276.

- Lopes PN, Salovey P, Straus R. Emotional intelligence, personality, and the perceived quality of social relationships. Pers Individ Differ. 2003;35(3):641‒658. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00242-8

- Petrides KV, Pita R, Kokkinaki F. The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. Br J Psychol. 2007;98(2):273‒289. doi:10.1348/000712606X120618

- Ghiabi B, Besharat MA. An investigation of the relationship between personality dimensions and emotional intelligence. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;30:416‒420. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.082

- Saklofske DH, Austin EJ, Minski PS. Factor structure and validity of trait emotional intelligence measure. Pers Individ Differ. 2003;34(4):707‒712. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00056-9

- Chamorro-Premuzic T, Bennett E, Furnham A. The happy personality: mediational role of trait emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Differ. 2007;42(8):1633‒1639. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.029

- Vernon PA, Willani VC, Schermer JA, Petrides KV. Phenotypic and genetic associations between the big five and trait emotional intelligence. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2008;11(5):524‒530. doi:10.1375/twin.11.5.524

- Tok S, Morali SL. Trait emotional intelligence, the big five personality dimensions and academic success in physical education teacher candidates. Soc Behav Pers Int J. 2009;37(7):921‒932. doi:10.2224/sbp.2009.37.7.921

- Di Fabio A. Beyond fluid intelligence and personality traits in social support: the role of ability based emotional intelligence. Front Psychol. 2015;6:395. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.0039525904886

- Di Fabio A, Palazzeschi L. Beyond fluid intelligence and personality traits in scholastic success: trait emotional intelligence. Learn Individ Differ. 2015;40:121‒126. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2015.04.001

- Augusto Landa JM, Martos MP, Lopez-Zafra E. Emotional intelligence and personality traits as predictors of psychological well-being in Spanish undergraduates. Soc Behav Pers. 2010;38(6):783‒793. doi:10.2224/sbp.2010.38.6.783

- Siegling AB, Furnham A, Petrides KV. Trait emotional intelligence and personality: gender-invariant linkages across different measures of the big five. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2014;33(1):57‒67. doi:10.1177/0734282914550385

- Ven der Zee K, Wabeke R. Is trait-emotional intelligence simply or more than just a trait? Eur J Pers. 2004;18(4):243‒263. doi:10.1002/per.517

- De Raad B. The trait-coverage of emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Differ. 2005;38(3):673‒687. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.022

- Atta M, Ather M, Bano M. Emotional intelligence and personality traits among university teachers: relationship and gender differences. Int J Bus Soc Sci. 2013;4(17):253‒259.

- Petrides KV, Vernon PA, Schermer JA, Ligthart L, Boomsma DI, Veselka L. Relationships between trait emotional intelligence and the big five in the Netherlands. Pers Individ Differ. 2010;48(8):906‒910. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.019

- Geng Y. Gratitude mediates the effect of emotional intelligence on subjective well-being: a structural equation modeling analysis. J Health Psychol. 2016;23(10):1378‒1386. doi:10.1177/1359105316677295

- Rey L, Extremera N. Positive psychological characteristics and interpersonal forgiveness: identifying the unique contribution of emotional intelligence abilities, big five traits, gratitude and optimism. Pers Individ Differ. 2014;68:199‒204. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.030

- Wilks DC, Neto F, Mavroveli S. Trait emotional intelligence, forgiveness, and gratitude in Cape Verdean and Portuguese students. S Afr J Psychol. 2014;45(1):93‒101. doi:10.1177/0081246314546347

- Ludovino EM. Emotional Intelligence for IT Professionals. Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing Ltd; 2017.

- Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Bobik C, et al. Emotional intelligence and interpersonal relations. J Soc Psychol. 2001;141(4):523‒536. doi:10.1080/00224540109600569

- Furnham A, Petrides KV. Trait emotional intelligence and happiness. Soc Behav Pers. 2003;31(8):815‒824.

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Positive emotions and emotional intelligence In: Barrett LF, Salovey P, editors. Emotions and Social Behavior. The Wisdom in Feelings: Psychological Processes in Emotional Intelligence. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002:319‒340.

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(1):81‒90. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

- Zawadzki B, Strelau J, Szczepaniak P, Śliwińska M. Inwentarz osobowości NEO-FFI Costy i McCrae. Podręcznik do polskiej adaptacji. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP; 1998.

- Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64(4):241‒256. doi:10.1037/a0015309

- Lucas RE, Diener E, Grob A, Suth EM, Shao L. Cross-cultural evidence for the fundamental features of extraversion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(3):452‒468. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.452

- Costa PT, McCrae RR, Dye DA. Facet scales for agreeableness and conscientiousness: a revision of the NEO personality inventory. Pers Individ Differ. 1991;12(9):887‒898. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(19)90177-D

- Jaworowska A, Matczak A. Kwestionariusz Inteligencji Emocjonalnej INTE. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych; 2008.

- Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Hall LE, et al. Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Differ. 1998;25(2):167‒177. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00001-4

- Kossakowska M, Kwiatek M. Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza do badania Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza do badania wdzięczności GQ-6. Przeglad Psychol. 2014;57:503–514.

- Bickel PJ, Freedman DA. Asymptotic normality and the bootstrap in stratified sampling. Ann Stat. 1984;470‒482.

- Gravetter F, Wallnau L. Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. California: Wadsworth; 2014.

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New Jersey, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2013.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173‒1182. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Alegre A, Perez-Escoda N, Lopez-Cassa E. The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and personality. is trait el really anchored within the big five, big two and big one frameworks. Front Psychol. 2019;10(866):1‒9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00866/full

- Mathews MA, Green JD. Looking at me, appreciating you: self-focused attention distinguishes between gratitude and indebtedness. Cogn Emot. 2009;24(4):710‒718. doi:10.1080/02699930802650796

- Wood AM, Joseph S, Linley PA. Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26(9):1076‒1093. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.9.1076

- Van Dusen JP, Tiamiyu MF, Kashdan TB, Elhai JD. Gratitude, depression and PTSD: assessment of structural relationship. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(3):867‒870. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.11.036

- Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: a meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to morality. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(6):887‒919. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887

- Simão C, Seibt B. Gratitude depends on the relational model of communal sharing. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86158. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.008615824465933

- Kee YH, Tsai YM, Chen LH. Relationships between being traditional and sense of gratitude among Taiwanese high school athletes. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(3):920‒926. doi:10.2466/PR0.102.3.920-926

- McAdams DP. The Art and Science of Personality Development. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2015.

- Kline R, Bankert A, Kraft PM. Personality and prosocial behavior: a multilevel meta-analysis. Political Sci Res Methods. 2017;7(1):125‒142. doi:10.1017/PSRM.2017.14

- Miklikowska M. Psychological underpinnings of democracy: empathy, authoritarianism, self-esteem, interpersonal trust, normative identity style, and openness to experience as predictors of support for democratics values. Pers Individ Differ. 2012;53(5):603‒608. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.032

- Sun P, Liu Z, Guo Q, Fan J. Shyness weakens the agreeableness-prosociality association via social self-efficacy: a moderated-mediation study of Chinese undergraduates. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1084. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.0108431139123

- Grant AM, Gino F. A little thanks goes a long way: explaining why gratitude expressions motivate prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(6):946‒955. doi:10.1037/a0017935

- Wood AM, Maltby J, Stewart N, Linley PA, Joseph S. A social-cognitive model of trait and state levels of gratitude. Emotion. 2008;8(2):281‒290. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.281

- Bar-On R. EQ-I Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems; 1997.

- Callea A, De Rosa D, Ferri G, Lipari F, Costanzi M. Are more intelligent people happier? Emotional intelligence as mediator between need for relatedness, happiness and flourishing. Sustainability. 2019;11(4):1022. doi:10.3390/su11041022

- Goleman D. Working with Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books; 1998.