Abstract

With a growing number of disease-modifying therapies becoming available for relapsing multiple sclerosis, there is an important need to gather real-world evidence data regarding long-term treatment effectiveness and safety in unselected patient populations. Although not providing as high a level of evidence as randomized controlled trials, and prone to bias, real-world studies from observational studies or registries nevertheless provide crucial information on real-world outcomes of a given therapy. In addition, evaluation of treatment satisfaction and impact on quality of life are increasingly regarded as complementary outcome measures. Fingolimod was the first oral disease-modifying therapy approved for relapsing multiple sclerosis. This review aims to summarize current knowledge on the long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes of multiple sclerosis patients on fingolimod. Impact on treatment satisfaction and quality of life will be discussed according to available data.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory demyelinating and neurodegenerative disease of the central nervous system (CNS).Citation1 It affects over 2.3 million people worldwide, and is the most common cause of atraumatic disability in young adults. Its most common clinical presentation is relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS; 85%–90%), in which subacute bouts of neurological worsening seem to be driven at least partly by invasion of the CNS by adaptive immune cells.Citation2,Citation3 As the disease evolves over time, there is disability progression (DP), resulting in reduced quality of life (QoL).Citation4 There is an increasing armamentarium of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs), both injectable and oral, with different mechanisms of action approved for relapsing MS. It is now recognized that the overall objective in treating MS includes preventing relapses, DP, and increase in CNS-lesion burden as seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These outcomes are included in the composite measure of no evidence of disease activity (NEDA).Citation5,Citation6 NEDA 4 also includes follow-up of brain-volume loss as surrogate marker for neurodegeneration and disability worsening.

Phase III randomized controlled trials assess the short-term efficacy and safety of DMTs in a strictly preselected patient population. Real-world evidence (RWE) is defined as data regarding a treatment that are not collected in a randomized controlled trial.Citation7 RWE is gathered in unselected patient populations and can provide more generalizable data and also long-term evidence on a wide variety of end points such as effectiveness, safety or other outcomes, such as patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Despite existing bias, due to the non-randomized setting in which data is collected, RWE can still provide evidence that can be used for post-marketing decision making by health care providers or regulatory authorities.Citation8 There is however an unmet need for RWE data, regarding long-term outcomes on more recently introduced DMTs, to understand their comparative benefits in this complex and evolving landscape.

PROs are increasingly recognized as complementary outcomes measures to classical end points not captured by classical measures, such as the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). They can provide additional insight on disease status by evaluating mood, fatigue, treatment satisfaction, and QoL.Citation9 In the setting of MS, a large-scale European survey recently showed that reported decreases in QoL were correlated with increasing disease severity in the domains of mobility, self-care, usual activities, and pain/discomfort.Citation10

Traditional injectable DMTs, such as IFNβ and glatiramer acetate, have been the mainstay of first-line RRMS treatment for the past two decades and have overall good safety profiles. However, the efficacy of these agents may be limited in some patients.Citation11,Citation12 In addition, the need for long-term self-administration of injections imposes a significant burden on patients, because of tolerability issues and injection-site-related side effects.Citation13,Citation14 This can be responsible for reduced treatment persistence in the long run and potentially affects QoL.Citation15

Fingolimod (Gilenya; Novartis International AG, Basel, Switzerland) is a sphingosine 1 phosphate-receptor modulator that selectively and reversibly retains naïve and central memory T-lymphocytes within lymph nodes, thereby preventing them from circulating to other tissues, including the CNS.Citation16 It was the first oral therapy approved to treat relapsing MS by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in September 2010. The European Medicines Agency approved fingolimod for rapidly evolving severe MS or failure of first-line therapy in RRMS in January 2011. In total, three Phase III studies – FREEDOMS, FREEDOMS II, and TRANSFORMS – demonstrated the efficacy of fingolimod in reducing the annualized relapse rate (ARR) and improving MRI outcomes, including slowing of brain-volume loss compared with placebo or intramuscular IFNβ1a.Citation17–Citation19

By May 31, 2017, it was estimated that over 213,000 patients worldwide had been treated with fingolimod, resulting in 453,000 patient-years of exposure (Novartis International AG, data on file, September 2017). This underscores the importance of gathering RWE concerning the long-term outcomes of treatment with fingolimod. This review aims to summarize current knowledge on the long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes of MS patients on fingolimod. Impact on treatment satisfaction and QoL is discussed according to available data.

Materials and methods

A bibliographic search was performed in PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) and on published abstracts from the following international congresses: Annual Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis, Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, Annual Meeting of the European Neurological Society, European Academy of Neurology Congress, and congresses of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. Keywords used were fingolimod, multiple sclerosis, effectiveness, safety, open-label, extension, quality of life, patient-reported outcomes, long-term, and observational.

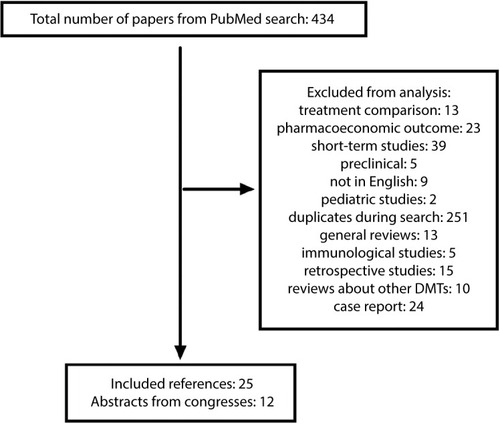

Only studies reporting effectiveness or safety with a follow-up of more than 2 years were selected for review. Studies including PROs and QoL measures were retained regardless of fingolimod-treatment duration. illustrates the process of selection of published papers and congress abstracts for this review.

Efficacy from clinical trials and real-world effectiveness of fingolimod

Efficacy from pivotal Phase III clinical trials

FREEDOMS, FREEDOMS II, and TRANSFORMS were three large, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, pivotal Phase III clinical trials for fingolimod in patients with RRMS.Citation17–Citation19 In the 24-month FREEDOMS trial,Citation17 daily 0.5 mg fingolimod significantly reduced the ARR by 54% (P<0.001) and risk of 6-month confirmed DP (CDP) by 37% (P=0.01) relative to placebo. Across the study duration, the number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions (GELs) was reduced by 79%, number of new or enlarged T2 lesions by 74%, and brain-volume loss by 36% (P<0.001 for all).

In TRANSFORMS,Citation18 the ARR at 1 year was reduced by 52% in 0.5 mg fingolimod-treated patients compared to those treated with intramuscular IFNβ1a (P<0.001). GELs were reduced by 55% (P<0.001), new or enlarged T2 lesions by 35% (P<0.004), and brain-volume loss by 31% (P<0.001). The risk of DP was reduced by 29% (nonsignificant versus active comparator).

The FREEDOMS II trialCitation19 was similar in design and objectives to FREEDOMS, except that it included additional outcome measures at the request of the FDA. The ARR was reduced by 48% in 0.5 mg fingolimod-treated patients relative to placebo (P<0.0001), number of GELs by 70% (P<0.0001), number of new or enlarged T2 lesions by 74% (P<0.0001), and brain-volume loss by 31% (P<0.0002). A post hoc analysis showed that the 3 month CDP was reduced by 30% (P=0.04) in patients with an EDSS score above 0.

Efficacy from the Phase II and III extension trials

In the Phase II extension study, patients receiving placebo were rerandomized to daily fingolimod 5 mg or 1.25 mg. At month 24, patients on fingolimod 5 mg were switched to fingolimod 1.25 mg, and at month 60 all patients were switched to fingolimod 0.5 mg, due to safety considerations.Citation20 Median treatment duration was 5.1 years, and 122 patients completed the study with over 7 years of treatment (). Overall, in patients treated for at least 6 months (n=243), the ARR remained low (0.17), 60.9% were free from relapse, and 82% from 6 month CDP. MRI outcomes were also favorable, with 84%–96% of patients free of GELs between years 1 and 7, regardless of initial randomization (). Throughout the study period, 68%–88% of patients were free from new or enlarging T2 lesions.

Table 1 Clinical end points from the fingolimod extension studies

Table 2 Radiological endpoints of fingolimod extension studies

The extensions of the three pivotal fingolimod Phase III trials also provided evidence of the prolonged efficacy of the treatment. It must be noted that both 0.5 mg and 1.25 mg fingolimod doses were initially evaluated in the extension studies. In FREEDOMS and FREEDOMS II, patients on placebo who were enrolled in the extension phase were initially rerandomized to either daily fingolimod 0.5 mg or 1.25 mg.Citation21 Similarly, in the extension of the TRANSFORMS study, patients on fingolimod remained on the same dose, although blinding was maintained, while patients on IFNβ1a were rerandomized at a 1:1 ratio to either fingolimod 0.5 mg or 1.25 mg.Citation22 Ultimately, all remaining patients were switched to fingolimod 0.5 mg in the open-label extension (LONGTERMS, NCT01201356) upon implementation of a protocol amendment in 2009. Dropout rates and reasons for drug discontinuation from these studies are listed in . Overall, retention rates were 76%–93%, including the long-term extension study. Of note, only 13% of patients discontinued fingolimod during the LONGTERMS extension. During the Phase III trials and their extensions, 19%–36% of patients stopped fingolimod due to adverse events.

Table 3 FU and treatment-discontinuation rates in Phase III clinical trials and the LONGTERMS extension

In the 2-year extension of FREEDOMS, in patients continuously treated with fingolimod 0.5 mg per day, the ARR remained low (): 59.3% of patients (95% CI 54.2%–64.4%) remained free of relapse, while 80% (95% CI 76%–84%) were free of 6-month CDP. The mean number of GELs measured during 48 months was 1.1 in comparison to 1.6 at baseline, before randomization (). Analysis of individual measures of disease activity in the extension study of the pooled cohorts of the pivotal FREEDOMS and FREEDOMSII trials at 4 years showed better outcomes in treatment-naïve patients compared to those previously exposed to DMTs.Citation23

In the 4.5-year extension of TRANSFORMS, in patients who received 0.5 mg of fingolimod throughout the study, the ARR during study extension was 0.16 (95% CI 0.12–0.19); 75% of patients remained free of new GELs and 42% of new or enlarging T2 lesions ( and ). Preliminary results from the LONGTERMS study show that 50% of patients remain free of GELs (n=924) and that 35% remain free of new or enlarging T2 lesions (n=595) up to year 5 ().Citation24 Post hoc analysis of the TRANSFORMS and extension studies showed that 44.6%–78.3% of patients continuously on fingolimod or switching from IFNβ1a achieved NEDA 3 status from year 1 through year 8. NEDA 4 status, including mean yearly brain-volume loss ≤0.4%, was also sustained in 26.6%–53.2% of patients during the same yearly intervals.Citation25

Long-term real-world effectiveness of fingolimod

Although a number of studies have been published regarding the effectiveness of fingolimod in an real-world (RW) setting, most report outcomes at 1 or 2 years and have recently been reviewed elsewhere.Citation26 PANGAEA is a large-scale postmarketing study aiming to provide long-term safety and effectiveness data on 4,229 MS patients treated with fingolimod in Germany.Citation27 A pharmacoeconomic substudy is ongoing, including 800 patients, that collects QoL, treatment-satisfaction, and health-resource consumption data through PROs. Interim results have already been communicated regarding certain outcomes of the study in a population of 4,016 patients, with mean exposure to fingolimod of 2.8 (SD 1.7) years.Citation28 Regarding effectiveness, the reported year 3–5 ARR in patients is 0.27 (). During this interval, 76%–78.4% of patients were free of relapses and 85% free from 6-month CDP. Overall, 42.3%–44.4% of patients remained free of clinical disease activity during years 3 and 4 of treatment. No imaging outcomes have yet been communicated in this study.

Table 4 Clinical effectiveness in patients treated with fingolimod for more than 2 years

A retrospective study reported RW results on fingolimod effectiveness in a cohort of 249 patients, with mean treatment duration of 2.7 (SD 2.2) years.Citation29 At year 3, 62% of patients were relapse-free and 51% remained free of clinical disease activity (). Regarding MRI outcomes, 74% of patients remained free of GELs during year 3 and 23% were free of new or enlarging T2 lesions. As a whole, 36% of patients still fulfilled the NEDA 3 criteria at that time point.

Long-term safety of fingolimod

The safety profile of fingolimod up to 2 years was defined during the Phase II and III clinical trials, and includes (among others) first-dose-related bradycardia, macular edema, hypertension, severe lymphopenia, and elevation of liver enzymes. An integrated analysis of safety data from clinical studies, their extension, and postmarketing safety data up to December 2011 has not identified any unexpected or new safety signals.Citation30 shows the incidence of adverse events of special interest or serious adverse events during the Phase III trials and the LONGTERMS extension up to 10 years, as well as in the large-scale RW studies PANGAEA and VIRGILE.Citation31–Citation33 Overall, incidence rates of the reported events were consistent with the known safety profile of fingolimod, except for cryptococcal infections and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), which emerged in the postmarketing setting.

Table 5 AEs of special interest and SAE rates during the Phase III trials, the LONGTERMS extension, and the real-world studies PANGAEA and VIRGILE

Infections

In the extension of the FREEDOMS study, herpes virus infections (n=99) were reported in 9%–12.1% of patients across treatment groups.Citation21 Similar rates were recorded during the extension of the TRANSFORMS study (10.1%–15% across treatment groups in six patients).Citation22 In the postmarketing setting, there have been 13 confirmed cases of PML in patients on fingolimod not attributed to previous treatment with natalizumab (Novartis, data on file). Twelve cases occurred after 2 years of treatment. Over 79,000 patients worldwide have been treated for 2 years or longer with fingolimod. Therefore, the PML risk in patients treated with fingolimod for more than 2 years is estimated to be 0.152 per 1,000 patients (95% CI 0.078–0.265), corresponding roughly to one in 6,000 patients. Cases of carryover PML following switches from natalizumab to fingolimod have been reported, but no precise estimate is available on their incidence.Citation34

Rare cases of cryptococcal infection have been reported in patients on fingolimod, either cutaneous, meningeal or disseminated.Citation35–Citation37 Prescribing physicians should also be aware of the risk of herpes zoster or herpes simplex reactivation while on fingolimod therapy.Citation38–Citation41 The risk does not increase with the duration of exposure to fingolimod, and the reactivation is not necessarily more severe, but exposure to intravenous corticosteroids for relapse might be a risk factor.Citation42 Before initiating fingolimod treatment, it is mandatory to verify whether the patient has been immunized for the varicella zoster virus, and if not to vaccinate accordingly.

Malignancies

In the extension of the FREEDOMS study, 17 cases of malignancy occurred, among which there were ten cases of basal-cell carcinoma (0–1.4% across treatment groups).Citation21 Similar rates were also reported during the extension of the TRANSFORMS study.Citation22 In total, 105 cases of basal-cell carcinoma have been reported within the fingolimod clinical trials and 111 cases in the postmarketing setting (Novartis, data on file). Clinical vigilance for suspicious skin lesions is thus warranted while patients are on fingolimod therapy, and should prompt referral to a dermatologist if needed.

Up to now, apart from basal-cell carcinoma, reported malignancy rates have been within the range of expected malignancies in the general and MS populations, but have prompted the inclusion of this adverse event in the prescribing information. Long-term safety data is however still needed collected from RW observational studies, especially regarding the use of the product in an unselected patient population, with possible comorbidities and potential interactions with other medications.

Cardiovascular safety

The adverse-event profile of fingolimod includes cardiovascular events, for which practical guidelines for treatment initiation and monitoring have been implemented. Expression of the S1P1 receptor is not restricted to lymphocytes, but is also present on atrial myocytes, thereby explaining the transient negative chronotropic effect seen upon first-dose intake of fingolimod.Citation43

In the Phase III FREEDOMS and FREEDOMS2 trials, bradycardia, first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, and second-degree AV block were reported in 1.4%, 2.8%, and 0.1%, respectively, of patients upon treatment initiation with fingolimod 0.5 mg.Citation17,Citation19 Mean elevations of 3 mmHg systolic and 1 mmHg diastolic blood pressure were also reported. This has prompted open-label studies (FIRST, START) on the outcome of cardiac monitoring upon first-dose intake ().Citation44,Citation45 These studies have provided evidence that bradycardia is a transient, mostly asymptomatic event and that AV-conduction abnormalities are infrequent and recover spontaneously. In the FIRST study, the incidence of Mobitz type I second-degree AV block (4.1%) and 2:1 AV block (2%) was higher in patients with preexisting cardiac conditions versus those without (0.9% versus 0.3%), warranting precaution in these patients. Concomitant medications, such as selective serotonin-recapture inhibitor antidepressants or other drugs known to prolong the QT interval, β-blockers, or calcium-channel blockers did not show an effect on the incidence of cardiac adverse events.Citation44–Citation46

Table 6 Adverse events during first-dose heart-rate monitoring

Among the five patients who presented with cardiac adverse events during the 4-month follow-up of the FIRST study, 80% occurred within 48 hours of fingolimod initiation. Only two events led to drug discontinuation (unconfirmed angina pectoris and asymptomatic Mobitz I second-degree AV block).Citation44 Longer-term follow-up in the LONGTERMS or RW PANGAEA studies did not show new safety signals regarding cardiovascular safety.Citation31,Citation32

MS relapses with tumefacient demyelinating lesions

The occurrence of tumefacient demyelinating lesions in individual cases following either initiation or withdrawal of treatment with fingolimod has recently been comprehensively reviewed.Citation47 It demonstrates that in some patients, the redistribution of immune cells can have adverse effects promoting unusual disease activity. Immunological profiling studies are needed to understand the underlying mechanisms better.

Impact of fingolimod on quality of life and patient-reported outcomes

Clinical trial data

In the FREEDOMS II study, at 24 months no statistically significant differences in the EuroQol utility score, the Patient Reported Indices in Multiple Sclerosis nor the modified Fatigue Impact Scale were reported between fingolimod- and placebo-treated patients.Citation19

Real-world evidence

The EPOC study was a 6-month, randomized, open-label, multicenter trial with an optional 3-month extension, in which 1,053 patients were randomized at a 1:3 ratio to either fingolimod or an injectable DMT.Citation48 Patients (33.3%) were switched from glatiramer acetate to fingolimod and the remainder from subcutaneous or intramuscular IFNβ preparations. Patient satisfaction was measured by changes in the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication between baseline and 6 months. It improved significantly with fingolimod compared with the injectable DMT. The least-squares ± SE treatment difference was −17.5±1.68 (P<0.001). The improvement was also seen on the questionnaire subscales for effectiveness, side effects, and convenience. QoL measured with the SF-36 scale showed significant improvement in all components (physical health, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, role limitation due to emotional problems, and general mental health). Only score increases in the domains of physical functioning and general health perceptions were nonsignificant.

A substudy of PANGAEA collecting QoL, treatment satisfaction, and health-resource consumption data is ongoing. Preliminary results of this study have been reported on 662 patients, showing that 71.2% of patients estimated their overall state of health as stable or improved (16.9%) using the EQ-5D.Citation28 Individual (effectiveness and convenience) and overall treatment-satisfaction scores were increased up to 2 years in comparison to baseline. Recently, a substudy of PAN-GAEA on a small subset of patients showed improvements in cognition between 0 and 24 months using the single-digit modality test (n=83). The neuropsychological, mood, and fatigue subscores of the UK neurological disability score were also slightly improved during the first 2 years on fingolimod (n=187).Citation49

A 12-month study performed on 172 subjects treated with fingolimod and 75 with other DMTs assessed health-related QoL using the MusiQoL questionnaire at baseline and 6 and 12 months. For both treatment cohorts, there was no significant improvement in overall MusiQoL score versus baseline. There was, however, a slight improvement in the “psychological well-being subscore” for fingolimod-treated patients at months 6 and 12 (P=0.002 and P<0.01 versus baseline, respectively).Citation50

The VIRGILE study is an ongoing prospective observational study aiming to collect effectiveness and safety data in an RW setting. It also includes pharmacoepidemiological outcomes and assessment of the impact of fingolimod on QoL with the MusiQoL and EQ-5D questionnaires. The recruitment target is 1,200 fingolimod-treated patients, with a planned follow-up of 5 years. In addition, 600 patients on natalizumab will be recruited and followed for 3 years. Interim results show that all domains analyzed by the MusiQoL questionnaire are sustained between 6 and 24 months relative to baseline.Citation33,Citation51

Discussion

RWE is needed, to gain knowledge on long-term safety and effectiveness for recently introduced DMTs for MS. As the data are gathered in unselected populations, it can lead to several biases, which have been extensively reviewed by Kalincik and Butzkueven.Citation52 However, despite not providing the same level of evidence as a randomized controlled trial, RW studies can still inform health-care practitioners and other stakeholders of long-term clinical benefits and rare adverse events. In addition, postmarketing studies can include other unconventional measures, such as pharmacoeconomic evaluations of health-care resource utilization and impact of a given intervention on patient-reported outcomes, such as QoL.

With regard to fingolimod, long-term effectiveness comes from extension studies of the pivotal trials or from observational postmarketing studies or retrospective analysis of patient cohorts. The extension studies for fingolimod have shown sustained benefit on clinical and radiological outcomes in a significant proportion of patients. However, the results should be interpreted with caution, because of the bias introduced by patient dropouts due to adverse events, lack of efficacy, or termination of a study before all patients had reached a defined treatment duration. For example, only 60% of the intent-to-treat patients completed the Phase III fingolimod extension studies (). Follow-up has been extended to 10 years now and is ongoing in the LONGTERMS study. However, only 41.3% of the 3,168 patients enrolled in LONGTERMS have reached more than 2 years of treatment and only 25 have been treated continuously for 10 years. Results concerning brain-volume loss show an advantage for early versus late treatment with fingolimod, and annualized brain-atrophy rates reported up to 5 years in the LONGTERMS study show almost normalized rates of between −0.38 and −0.33.

Short-term RW-effectiveness studies have been extensively reviewed by Ziemssen et al.Citation26 The present review highlights the paucity of data available for treatment longer than 2 years. However, both interim results of PANGAEA and of the retrospective study by Izquierdo et al provide evidence for sustained effectiveness of fingolimod.Citation27,Citation29 In the latter study, 36% of patients fulfilled the NEDA 3 criteria at year 3 and more than 40% of patients in the PANGAEA study were free of clinical disease activity during years 3 and 4 of treatment (n=1,463 and n=763, respectively). Ongoing initiatives include PANGAEA and VIRGILE. Other national or international registries, such as MSBase, also aim at gathering long-term effectiveness data.Citation53 It should be noted, however, that these studies or others should include not only clinical but also radiological evidence of treatment effectiveness. In addition to conventional imaging outcomes, such as the number of GELs and T2 lesions, the rate of brain-volume loss could also be measured. MS-MRIUS is an ongoing multicenter observational study of patients treated with fingolimod in the US. It captures MRI data acquired in routine clinical practice during 24 months that will also be used for brain-volumetric analysis. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the proportion of patients achieving NEDA 3/4 status at 12 and 24 months.Citation54

Safety is an important concern for long-term DMT in MS. Until now, extension studies and PANGAEA have reported adverse events consistent with the known profile of fingolimod.Citation55 It must be noted, however, that rare adverse events having occurred while on fingolimod therapy are published as case reports. PML, Cryptococcus infection, hemophagocytic syndrome, Kaposi’s sarcoma, vasculopathy, or encephalopathy have been individually reported and reviewed recently by Fragoso.Citation56 These rare occurrences have (to our knowledge) not been captured in the long-term studies discussed herein. The primary end point of the international observational PASSAGE study (NCT01442194) is the incidence of collected adverse events. Other ongoing registries capturing safety data, such as BELTRIMS, might also contribute to collection of safety data on the long-term use of fingolimod in a RW setting.Citation59

This review of literature and congress abstracts shows that although the collection of PROs and QoL data is advocated as useful and complementary for a comprehensive multimodal assessment of treatment response, data on these outcomes remain scarce, notably for the RW use of fingolimod. The EPOC study demonstrated in a large cohort of patient transitioning from injectable DMTs to fingolimod an increase in all aspects of treatment satisfaction (effectiveness, convenience, and side effects) as well as a significant improvement in all QoL components of the SF-36 scale, except the physical functioning and general health domains.Citation48 These results were replicated in an independent cohort. Preliminary results of the PANGAEA substudy show 88% of patients estimated that their overall state of health was stable or improved on fingolimod at 2 years of treatment.Citation28 As in the EPOC study, treatment satisfaction was increased in comparison to baseline. The VIRGILE study, with enrolment of 1,200 patients on fingolimod planned, is another ongoing large-scale prospective study that includes QoL outcomes using other scales, such as the MusiQoL.

In conclusion, more data are needed on the long-term effectiveness and safety of fingolimod in unselected patient cohorts, as most postmarketing observational studies published until now have reported outcomes of 2 years or less. Several national or international initiatives are ongoing, gathering these data prospectively. There is, however, a lack of data on PROs. In the short term, EPOC provided evidence on treatment satisfaction and QoL after 6 months of treatment with fingolimod. The ongoing PANGAEA and VIRGILE studies will also provide information on QoL outcomes in an RW setting at 2 and 3 years, respectively. In order to obtain complete and informative data on long-term use of fingolimod, study protocols should comprehensively assess all relevant clinical and radiological outcome measures, in accordance with current recommendations.Citation57,Citation58

Disclosure

V van Pesch has received travel grants from Biogen, Bayer Schering, Sanofi Genzyme, Merck, Teva, Novartis Pharma and Roche. His institution receives honoraria for consultancy and lectures from Biogen, Bayer Schering, Sanofi Genzyme, Merck, Roche, Teva and Novartis Pharma as well as research grants from Novartis Pharma, Roche and Bayer Schering. S El Sankari has received travel grants from Biogen, Sanofi Genzyme, Merck and Teva. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SospedraMMartinRImmunology of multiple sclerosisAnnu Rev Immunol20052368374715771584

- TullmanMJOverview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosisAm J Manag Care2013192 SupplS15S2023544716

- FrischerJMBramowSDal-BiancoAThe relation between inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis brainsBrain2009132Pt 51175118919339255

- JanardhanVBakshiRQuality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: the impact of fatigue and depressionJ Neurol Sci20022051515812409184

- ZiemssenTDerfussTde StefanoNOptimizing treatment success in multiple sclerosisJ Neurol201626361053106526705122

- BanwellBGiovannoniGHawkesCLublinFEditors’ welcome and a working definition for a multiple sclerosis cureMult Scler Relat Disord201322656725877624

- GarrisonLPJrNeumannPJEricksonPMarshallDMullinsCDUsing real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: the ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force reportValue Health200710532633517888097

- TrojanoMTintoreMMontalbanXTreatment decisions in multiple sclerosis: insights from real-world observational studiesNat Rev Neurol201713210511828084327

- SonderJMBalkLJvan der LindenFABosmaLVPolmanCHUitdehaagBMToward the use of proxy reports for estimating long-term patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosisMult Scler201521141865187125257617

- KobeltGThompsonABergJGannedahlMErikssonJNew insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in EuropeMult Scler20172381123113628273775

- QizilbashNMendezISanchez-de la RosaRBenefit-risk analysis of glatiramer acetate for relapsing-remitting and clinically isolated syndrome multiple sclerosisClin Ther2012341159176.e522284996

- OliverBJKohliEKasperLHInterferon therapy in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the comparative trialsJ Neurol Sci20113021–29610521167504

- BrandesDWCallenderTLathiEO’LearySA review of disease-modifying therapies for MS: maximizing adherence and minimizing adverse eventsCurr Med Res Opin2009251779219210141

- MenzinJCaonCNicholsCWhiteLAFriedmanMPillMWNarrative review of the literature on adherence to disease-modifying therapies among patients with multiple sclerosisJ Manag Care Pharm2013191 Suppl AS24S4023383731

- TreadawayKCutterGSalterAFactors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MSJ Neurol2009256456857619444532

- HofmannMBrinkmannVZerwesHGFTY720 preferentially depletes naive T cells from peripheral and lymphoid organsInt Immunopharmacol2006613–141902191017161343

- KapposLRadueEWO’ConnorPA placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosisN Engl J Med2010362538740120089952

- CohenJABarkhofFComiGOral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosisN Engl J Med2010362540241520089954

- CalabresiPARadueEWGoodinDSafety and efficacy of fingolimod in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (FREEDOMS II): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trialLancet Neurol201413654555624685276

- MontalbanXComiGAntelJLong-term results from a phase 2 extension study of fingolimod at high and approved dose in relapsing multiple sclerosisJ Neurol2015262122627263426338810

- KapposLO’ConnorPRadueEWLong-term effects of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis: the randomized FREEDOMS extension trialNeurology201584151582159125795646

- CohenJAKhatriBBarkhofFLong-term (up to 4.5 years) treatment with fingolimod in multiple sclerosis: results from the extension of the randomised TRANSFORMS studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201687546847526111826

- HohlfeldRKapposLTomicDEarly fingolimod treatment improves disease outcomes at 2 and 4 years in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisNeurology20178816 Suppl6332

- CohenJTenenbaumNBhattAPimentelRKapposLRadiological evidence of the long-term effect of fingolimod treatment in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosisNeurology20178816 Suppl4409

- CohenJHartungHKhatriBEarly switch to fingolimod for achieving no evidence of multiple sclerosis disease activity: 8-year analysis of data from the TRANSFORMS studyNeurology20178816 Suppl4390

- ZiemssenTMedinJCoutoCAMitchellCRMultiple sclerosis in the real world: a systematic review of fingolimod as a case studyAutoimmun Rev201716435537628212923

- ZiemssenTKernRCornelissenCThe PANGAEA study design: a prospective, multicenter, non-interventional, long-term study on fingolimod for the treatment of multiple sclerosis in daily practiceBMC Neurol2015159326084334

- ZiemssenTAlbrechtHHaasJ5 Years effectiveness of fingolimod in daily clinical practice: results of the non-interventional study PANGAEA documenting RRMS patients treated with fingolimod in GermanyNeurology20178816 Suppl6345

- IzquierdoGDamasFParamoMDRuiz-PenaJLNavarroGThe real-world effectiveness and safety of fingolimod in relapsing- remitting multiple sclerosis patients: an observational studyPLoS One2017124e017617428453541

- KapposLCohenJCollinsWFingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis: an integrated analysis of safety findingsMult Scler Relat Disord20143449450425877062

- CohenJTenenbaumSBhatRPimentelRKapposLLong-term efficacy and safety of fingolimod in patients with RRMS: 10-year experience from LONGTERMS studyMult Scler J2017233 SupplP1879

- ZiemssenTAlbrechtHHaasJ5 Years safety experience with fingolimod in real world: results from PANGAEA, a non-interventional study of RRMS patients treated in GermanyMult Scler J2017233 SupplP1192

- Lebrun-FrenayCPapeixCKobeltGLong-term efficacy, safety, tolerability and quality of life with fingolimod treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis in real-world settings in France: VIRGILE two-year resultsMult Scler J2017233 SupplEP1716

- KillesteinJVennegoorAvan GoldeAEBourezRLWijlensMLWattjesMPPML-IRIS during fingolimod diagnosed after natalizumab discontinuationCase Rep Neurol Med2014201430787225506447

- AchtnichtsLObrejaOConenAFuxCANedeltchevKCryptococcal meningoencephalitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimodJAMA Neurol201572101203120526457631

- ForrestelAKModiBGLongworthSWilckMBMichelettiRGPrimary cutaneous Cryptococcus in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimodJAMA Neurol201673335535626751160

- SetoHNishimuraMMinamijiKDisseminated cryptococcosis in a 63-year-old patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimodIntern Med201655223383338627853088

- HagiyaHYoshidaHShimizuMHerpes zoster laryngitis in a patient treated with fingolimodJ Infect Chemother2016221283083227553068

- PfenderNJelcicILinnebankMSchwarzUMartinRReactivation of herpesvirus under fingolimod: a case of severe herpes simplex encephalitisNeurology201584232377237825957334

- IssaNPHentatiAVZV encephalitis that developed in an immunized patient during fingolimod therapyNeurology20158419910025416038

- KawiorskiMMViedma-GuiardECosta-FrossardLCorralIPolydermatomal perineal and gluteal herpes zoster infection in a patient on fin-golimod treatmentEnferm Infecc Microbiol Clin201533213813924958672

- ArvinAMWolinskyJSKapposLVaricella-zoster virus infections in patients treated with fingolimod: risk assessment and consensus recommendations for managementJAMA Neurol2015721313925419615

- SubeiAMCohenJASphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators in multiple sclerosisCNS Drugs201529756557526239599

- GoldRComiGPalaceJAssessment of cardiac safety during fingolimod treatment initiation in a real-world relapsing multiple sclerosis population: a phase 3B, open-label studyJ Neurol2014261226727624221641

- LimmrothVHaverkampWDechendRFirst dose effects of fingolimod: final results of an in-depth ECG and Holter study in 6,998 German RRMS patientsMult Scler J2017233 SupplP764

- BermelRAHashmonayRMengXFingolimod first-dose effects in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis concomitantly receiving selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitorsMult Scler Relat Disord20154327328026008945

- YoshiiFMoriyaYOhnukiTRyoMTakahashiWNeurological safety of fingolimod: an updated reviewClin Exp Neuroimmunol20178323324328932291

- FoxEEdwardsKBurchGOutcomes of switching directly to oral fingolimod from injectable therapies: results of the randomized, open-label, multicenter, Evaluate Patient OutComes (EPOC) study in relapsing multiple sclerosisMult Scler Relat Disord20143560761926265273

- ZiemssenTAlbrechtHHaasJ5 Years effectiveness of fingolimod in daily clinical practice: results of the non-interventional study PANGAEAMult Scler J2017233 SupplP745

- AchironAArefHInshasiJEffectiveness, safety and health-related quality of life of multiple sclerosis patients treated with fingolimod: results from a 12-month, real-world, observational PERFORMS study in the Middle EastBMC Neurol201717115028784108

- PapeixCLebrun-FrenayCLerayELong-term efficacy, safety, tolerability and quality of life with fingolimod treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis in real-world settings in France: VIRGILE one-year resultsMult Scler J2016223 SupplP1234

- KalincikTButzkuevenHObservational data: understanding the real MS worldMult Scler201622131642164827270498

- FlacheneckerPBuckowKPugliattiMMultiple sclerosis registries in Europe: results of a systematic surveyMult Scler201420111523153224777278

- Weinstock-GuttmanBMedinJKhanNAssessing no evidence of disease activity status in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis receiving fingolimod: results from a longitudinal, multicenter, real-world studyNeurology8816 Suppl4388

- ZiemssenTAlbrechtHHaasJ5 Years safety of fingolimod in real world: first results from PANGAEA, a non-interventional study of RRMS patients treated with fingolimod, on safety and adherence after 5 years of fingolimod in daily clinical practiceNeurology20178816 Suppl5365

- FragosoYDMultiple sclerosis treatment with fingolimod: profile of non-cardiologic adverse eventsActa Neurol Belg2017117482182728528469

- ZiemssenTKernRThomasKMultiple sclerosis: clinical profiling and data collection as prerequisite for personalized medicine approachBMC Neurol20161612427484848

- GiovannoniGTomicDBrightJRHavrdováE“No evident disease activity”: the use of combined assessments in the management of patients with multiple sclerosisMult Scler20172391179118728381105

- van PeschVBELTRIMS: First results from a Belgian registry for treatments in Multiple SclerosisNewsletter of the Belgian Charcot Foundation2017425 Avaialble from: http://www.fondation-charcot.org/en/newsletters/35/ms-research-beltrims-registry-fund-charcot-belgianAccessed November 22, 2017.