Abstract

Atopic eczema is a common pediatric skin disorder. This review examines the use of pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of acute and chronic stages of the disease. The standard therapy is the treatment of acute flares with topical medications including pimecrolimus. The use of pimecrolimus cream for the first sign and symptoms of atopic eczema reduces the occurrence of flares as defined by the need for topical corticosteroids. The side effects of pimecrolimus cream are mild without any increase of infections or systemic immune suppression.

Introduction

Atopic eczema (AE) (atopic dermatitis) is a common, inflammatory skin disorder that adversely affects many aspects of patients’ lives. The prevalence of AE among children is 18.1% in Italy, 20.6% in Norway, 14.4% in Denmark, and 17.2% in the United StatesCitation1–Citation4 making it one of the most common pediatric skin disease. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Phase 3 study found that AE prevalence was stabilizing or decreasing in developed countries (New Zealand, Ireland, Sweden, Germany, United Kingdom) but still increasing in developing countries (Mexico, Chile, Kenya, Algeria, and 7 countries in Southeast Asia).Citation5

AE is also the start of the Atopic March, which is the natural progression of allergies from the skin to the nose and lung. Approximately 30% to 50% of children with AE will develop asthma and 75% will develop allergic rhinitis.Citation6 Environmental and genetic evidence points to a defect in the skin barrier as a major contributor to the onset of AE and progression of the atopic march. The defect in the epithelial barrier of the skin may in part be due to mutations in the filaggrin gene, a key protein in the formation of the skin barrier. It is now hypothesized that improvement in the skin barrier will prevent the progression of AE to asthma.Citation7,Citation8

Clinical presentation of AE

AE typically presents in the first years of life with greater than 90% diagnosed in the first 5 years. AE is a clinical diagnosis and not a laboratory or histological diagnosis based on classic criteria of major and minor criteria ( and ). The classic distribution of these lesions varies with age: in infancy through early childhood, face, extensor and exposed skin surfaces are involved. In older children, flexural surfaces are more characteristically affected. In adults, the face, neck, chest, hands, and feet areas can also be affected. Other hallmarks include xerosis (dry skin) and pruritus, resulting in a vicious itch-scratch cycle. Excoriations may be apparent and, in the chronic state, result in lichenification of the skin. Recurrent skin infections by bacteria, viruses, and dermatophytes may also occur.

Table 1 Atopic eczema diagnostic criteriaCitation63

Table 2 Atopic eczema in infancy diagnostic criteriaCitation63

Pathogenesis of AE

Although the etiology of the disease is incompletely understood, AE is considered the product of complex interactions among the host’s environment, susceptibility genes, skin barrier dysfunction, and local and systemic immune system dysregulation, extensively reviewed by Bieber.Citation9 Briefly, breakdown of the skin barrier is recognized to be important in the development of AE; however, it is debated whether this event is secondary to the inflammatory response to irritants and allergens (“inside-outside hypothesis”) or whether the barrier damage itself drives disease activity (“outside-inside hypothesis”).Citation10 Clinical data have indicated that the extent of disease activity is correlated with skin barrier function.Citation11

The skin interaction with the underlying immune system is the next key step in the pathogenesis of AE. For the start of the allergic response in AE, allergen-specific IgE binds to mast cells in the skin through the high-affinity Fc receptor I (FcɛRI), resulting in mast-cell degranulation and the release of inflammatory mediators. During this process, the production of IgE by B cells depends on the support of T-helper 2 (Th2) cells.Citation12 The initial, acute phase of AE is thought to be dominated by Th2 cytokines, whereas the chronic stage is thought to be T-helper 1 (Th1)-dominated;Citation13–Citation15 however, there also is evidence that regulatory T (Treg) cells may play a role in the latter stageCitation16 in the control of the chronic inflammation.

Triggers of AE

Triggers can vary among patients, but commonly include detergents, soaps, toiletries containing alcohol or astringents, assorted chemicals, infectious agents, aeroallergens (eg, dust mites, animal dander), and certain foods.Citation17 Both food and environmental allergens have been implicated as offending agents in AE, but the incidence is variable among pediatric and adult populations. In adults, less than 2% of AE patients have a food allergy as an exacerbating factor.Citation18 In contrast, 10% to 33% of severe AE cases have an associated food allergy in infants and young children.Citation19,Citation20 The more severe AE is more likely that a food allergy exists and is a contributing factor. Thus, the diagnosis of a food allergy should be considered in young children who have generalized or severe AE, or those who have recalcitrant disease despite aggressive therapy. Milk, soy, egg, peanut, and wheat accounted for 90% of food allergies implicated in AE.Citation21 Elimination of offending foods can result in clinical improvement of AE.Citation22 In addition to foods, environmental aeroallergens can also be significant triggers in AE. Aeroallergens may be more important in older children and adults, as these populations are more likely to have become sensitized. More than 85% of adults with AE have evidence of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to environmental allergens.Citation23 In children with AE, IgE-mediated aeroallergen sensitization first appears between the ages of 2 to 5 years, and predominates over food allergies by age 5.Citation24 However, in many patients, aeroallergen sensitization is only relevant for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and not atopic dermatitis. Nevertheless, in a subset of atopic dermatitis patients inhalational or topical exposures to aeroallergens can exacerbate AE.Citation25,Citation26

Treatment of AE

The basic treatment of AE is good skin care and avoidance of the allergens, triggers and irritants. Basic skin care involves hydration and moisturization of the skin. The review will focus on the use of anti-inflammatory medication in the treatment of AE. During an acute infection, appropriate antibiotics can be used to treat the infectious trigger. However, the natural history of eczema has intermittent flares with erythema and increased pruritus. The treatment of flares involves the use of anti-inflammatory agents. The classic agent is topical corticosteroids (TCS). TCSs have been the predominant first-line treatment for moderate to severe AE for several decades.Citation27,Citation28 The potencies of TCSs range from very mild to very strong, and the choice among formulations is tailored to the severity of the disease and exacerbation and the area of the body that is affected. Cutaneous, potency-related side effects (eg, skin atrophy, striae, telangiectasias, acne rosacea, and perioral dermatitis) limit the long-term use of these agents.Citation29 However, their long-term application can be problematic in children because of the potential for side effects, particularly skin atrophy and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA)–axis suppression with extensive use of high-potency topical corticosteroids.Citation30,Citation31 Another potential problem with TCS is compliance, as many patients and parents express concerns regarding the prolonged use of these agents.Citation32

Therefore, in the last 10 years, two non-steroidal anti-inflammatory therapies have been developed and approved in the form of two topical calcineurin inhibitors–pimecrolimus cream (Elidel®, SDZ ASM 981; Novartis) and tacrolimus ointment (Protopic®, FK 506; Astellas Pharma). Pimecrolimus is available as a 1% cream and is approved in the US and Europe for the treatment of mild to moderate AE, in children over 2 years of age; in approximately 40 countries, pimecrolimus is also available for the treatment of infants (3 to 23 months of age).Citation33 Tacrolimus ointment is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe AE and is available as an ointment in two concentrations: 0.03% and 0.1% for the treatment of adults, and 0.03% for the treatment of children aged 2 to 15 years.Citation34

Both compounds bind with high affinity to the macrophilin-12 receptor and inhibit calcineurin, a calcium-dependent phosphatase that is required for activation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NF-AT). The inactive form of nuclear factor of activated T cells cannot enter the nucleus. Therefore, via blockage of NF-AT, these agents inhibit the inflammatory cascade produced pathologic T cells inhibiting expression of cytokines (IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and interferon-gamma).Citation35

Pimecrolimus, in addition to preventing expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the proliferation of T cells, also inhibits activation of co-receptors required for T-cell activation and prevents the release of inflammatory mediators from mast cells. Unlike TCSs and tacrolimus, pimecrolimus does not induce apoptosis in Langerhans cells.Citation35,Citation36

Clinical evidence

More than 3000 patients were treated with pimecrolimus for up to 2 years in clinical trials.Citation37,Citation38 in both adult and pediatric populations. The trials were designed in two basic schemes, one treating acute flares in 6-week double-blind placebo-control study and the second scheme was the treatment at the first sign of inflammation in a pro-active fashion to prevent acute flares of atopic dermatitis.Citation39 Improvement in AE was measured by three basic methods, Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI), Investigators’ Global Assessment (IGA) and reduction of flares needing topical corticosteroids. The EASI is a validated composite score comprising severity ratings of erythema, oedema/induration/papulation, excoriations and lichenification weighted according to the estimated percentage of affected body surface area (BSA) of each body region. For each body region (head/neck, upper limbs, trunk and lower limbs), an affected area score of 0 to 6 was assigned for the percentage of affected BSA (0% to 100%). The individual ratings for erythema, edema/induration/papulation, excoriations and lichenification were then added (0 to 3 for each of the four symptoms) before the sum of the individual symptoms (maximum = 12) was multiplied by the affected area score (maximum = 6) to give a maximum of 72. The head/neck subtotal was multiplied by 0.1, the upper limb subtotal by 0.2, the trunk subtotal by 0.3, and the lower limb subtotal by 0.4 before being summed (maximum EASI = 72).Citation40 The IGA is a physician assigned clinical score that ranges from 0 to 5 (none to very severe) on the physician determination of AE severity.

The pediatric trials have shown short-term efficacy in patients randomized 2:1 to 6 week trial of pimecrolimus treatment or vehicle followed by 20-week open label extension in children young as 3 months of age (). In the trial of 403 children and young adults (aged 1 to 17 years with an IGA score at baseline of 2 or 3 [mild or moderate AD]),Citation41 35% of the children treated with pimecrolimus were clear or almost clear of AE at 6 weeks, compared 18% children treated with the vehicle (p < 0.05). In the same trial, 60% of pimecrolimus-treated patients showed at least a one-point reduction in the IGA score by 6 weeks compared to 33% of vehicle-treated patients.Citation41 In the infant trial of 186 patients with a baseline IGA score of 2 or 3 (mild or moderate AE),Citation39 in addition to the other two pimecrolimus-treated patients showed significant improvement in IGA scores compared to placebo at the end of 6 week blinded trial. Similarly in another infant trial, 55% of the pimecrolimus-treated patients were almost or clear (IGA = 1 or 0) compared to 24% in vehicle group.Citation42 The adult trials were of similar design with 130 adults and open labeled study of 947 of patients from 3 months to 81 years of age ().Citation43–Citation45 In the adult trial, IGA scores also significantly improved in pimecrolimus group compared to placebo.

Table 3 Pimecrolimus pediatric trials

Table 4 Pimecrolimus adult trials

Pruritus

One of the clinical features of AE is intense pruritus. AE is often called the itchy skin that rashes. Pimecrolimus cream 1% showed improvement in pruritus by the eighth day in the infant in 70% of the children compared to 37% of the children treated with vehicle (p < 0.001). A similar effect was noted in children and adolescents, with 44% of pimecrolimus-treated patients reporting no (0) or mild (1) pruritus at Day 8, compared with 26% of vehicle-treated patients (p < 0.001).Citation46 In the adult trial of 130 patients, self-assessed pruritus severity scores had improved by at least 1 point (4-point scale of 0 to 3) in 45% of patients treated with pimecrolimus compared with 17% of those using vehicle (p = 0.0016).Citation47 A significant treatment effect was also observed shortly after initiating pimecrolimus treatment even in a group of eczema patients with moderate to severe pruritus. Within 2 days, 42% of pimecrolimus-treated compared with 27% of vehicle-treated patients scored their pruritus as mild or absent (pruritus score of 0 or 1; p = 0.040), and these treatment differences were maintained throughout the study.Citation48

Erythema/inflammation

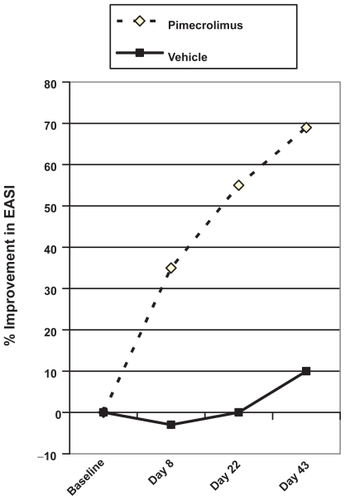

The other cardinal features of AE are erythema and inflammation. In one study of moderate AE in the adults, signs and symptoms improved progressively throughout the first 6 weeks of treatment, with a 33% reduction in EASI scores after the first 7 days and eczema score improved by 69.8% at the end of 6 weeks. In comparison, the patients treated with vehicle group had worsening eczema evidenced by an increase by 3.8% after 1 week and at Week 6 at 15.9% ().Citation47

Figure 1 Median percentage change in Eczema Area Severity Index (EASI) over time for pimecrolimus compared with vehicle. Drawn from data of Meurer et al.Citation43,Citation47

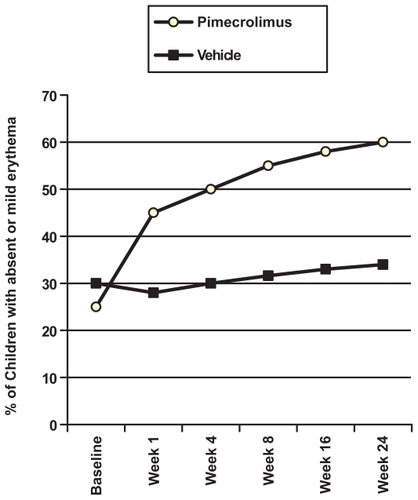

In the pediatric trials, improvement in eczema severity is also noted by changes in EASI scores. Pimecrolimus-treated patients with improvement within 1 week continued to improve during the length of the study (). Young children and adolescents showed improvements for each measure: for example, erythema; 61% of pimecrolimus-treated versus 37% of vehicle-treated at 6 weeks.Citation41 The improvement in eczema severity occurred in all age groups, including infants. Pimecrolimus reduced the signs of inflammation (erythema and infiltration) by 8 days in the infant trial. 61% of the patients treated with pimecrolimus had no or only mild erythema on all body areas, compared with 27% of patients treated with vehicle (p < 0.001). For infiltration, 67% patients treated with pimecrolimus had no or only mild symptoms on all body areas, compared with 40% in the vehicle group in the same infant trial.Citation42

Figure 2 Percentage of children with mild or absent erythema scores. Drawn from data of Eichenfield et al.Citation41

As mentioned earlier, patients also had short-term improvement in IGA scores. Long-term improvement was noted in a trial of 947 patients in a 1-year open-labeled study, aged from 3 months to 81 years; improvements in IGA were noted by 8 days in the total population.Citation43,Citation49 In the same study, 394 patients enrolled with moderate disease; 18% improved to IGA of 0 or 1 by 1 week, rising to 42% at day 168. With a similar study of 262 children with moderate eczema (IGA = 3) at baseline, 34.7% were clear or almost clear of eczema after 1 year of open-labeled treatment.Citation44 For the 87 children with severe/very severe AE (IGA = 4/5) at baseline, 18.4% were clear or almost clear of AE at 1 year, 19.5% had mild eczema (IGA = 2) and 31% improved to moderate disease (IGA = 3). These results indicate that all patients within varying severity can improve with pimecrolimus treatment.

Prevention of flares

AE is a chronic disease with periods of relapse and flares. Several trials examined the use of pimecrolimus form the start of symptoms to prevent flares in year-long trials in and children and adolescents. The use of pimecrolimus creams decreased over the year in both trials, indicating overall control with pimecrolimus. The total body surface area affected by eczema decreased over a year-long open-label trial from 24% to 7% in children/adolescent trial.Citation50 The time to first flare was substantial longer in the pimecrolimus-treated group compared to the vehicle treated group. In fact, 61% of children and adolescents in the pimecrolimus group were flare-free for 6 months and 51% were flare-free for 12 months of treatment, which is significantly more than the vehicle-treated group, as only 34% of patients in the control group at 6 months and 28% at 12 months were flare-free.Citation44 For the infants and toddlers, 68% were flare-free for 6 months of treatment, and 57% were flare-free for 12 months of treatment in the pimecrolimus-treated group. In contrast, in the control group, 30% and 28% of patients completed 6 and 12 months of treatment without flares, respectively.Citation39 In similar studies with pimecrolimus in adults, the prevention of flares can also be observed. In an identical designed trial but of 24 weeks’ duration, more adults patients with moderate AE treated with pimecrolimus remained in remission and experienced no major flares compared to vehicle group (pimecrolimus/vehicle: 59.7% vs 22.1%, p = 0.001).Citation47

Long-term treatment of AE

The alternative strategy to prevent flares is to use medications in a preventative fashion, as in in asthma, another atopic disease. Several recent trials have tried this strategy of medication on a regular basis 2 to 4 times a week to prevent flares even before the start of symptoms. Studies have examined both the use of topical steroids (fluticasone) or tacrolimus ointment three times a week to reduce the incidence of flares (). 348 patients (231 children, 117 adults) were randomized at a 2:1 ratio to either intermittent fluticasone propionate (FP) or vehicle, once daily 4 days per week for 4 weeks followed by once daily 2 days per week for 16 weeks. The patients on the active therapy were 7.7 times less likely to have a AE flare.Citation51 A second trial of similar design examined FP 2 days week compared to placebo for prevention of flares in 295 patients (12 to 65 years of age). The time to first relapse was 6 weeks for placebo compared to 16 weeks for FP.Citation52 In the Breneman study with tacrolimus three times a week, 197 adult patients were randomized to tacrolimus (125) and vehicle (72). The tacrolimus had more flare-free days (177 for tacrolimus and 134 for vehicle, p = 0.003). Also, the time for first relapse was 169 days for tacrolimus and 43 for vehicle, significantly better for the active therapy (p = 0.037).Citation53 A similar study in pediatrics showed a significant effect of 105 patients using tacrolimus three times a week compared to placebo after 16-week open-label run-in with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. The patients on tacrolimus arm had significantly more disease-free days and longer time to first relapse.Citation54 The third tacrolimus study examined 224 adults randomized to either tacrolimus or placebo twice a week to prevent flares. The active therapy (tacrolimus) increased the time to first flare from 15 to 142 days compared to placebo treatment.Citation55 The fourth study examined 250 children randomized to either tacrolimus or placebo twice a week to prevent flares. Similar to adult study, the active therapy (tacrolimus) increased the time to first flare from 38 days to 178 days. Also, the number of flares decreased in tacrolimus group compared to placebo.Citation56

Table 5 Long-term treatment trials for atopic eczema

Safety

For the use of any medications, the issue of safety is important (both local and systemic). For topical calcineurin inhibitors, the local side effects would be confined to the skin. During randomized trials using pimecrolimus, the most commonly reported form of application-site reaction in children and adults was a sensation of burning at the application site. Interestingly, it was reported at a similar rate in both vehicle- and pimecrolimus-treated children (10.4% of pimecrolimus-treated versus 12.5% of vehicle-treated patients).Citation41

For the systemic side effects, pimecrolimus would need to be absorbed at high levels. However, the use of pimecrolimus cream in AE does not lead to any significant levels in the circulating blood system. In pharmacokinetic studies of children with moderate to severe AE with up to 92% BSA affected, 67% of samples had pimecrolimus blood concentrations below 0.5 ng/mL and 97% of blood concentrations were in the range of 0.5 to 2.0 ng/mL. Also, for rat, pig, and human skin, pimecrolimus demonstrated a 9- to 10-fold lower permeation through skin in vitro than tacrolimus when comparing identical solutions of both compounds.Citation36 Patients treated with pimecrolimus in the AD trial have normal T and B cell function as evidenced by response to vaccination and delayed hypersensitivity response. Cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction against a range of antigens is a common method of assessing immunocompetence. DTH testing was used to test immune function in one study of pimecrolimus cream 1% with a total of 112 subjects who completed 1 year of treatment (82 pimecrolimus cream 1%; 30 vehicle).Citation44 Pimecrolimus had no effect on DTH testing with similar response to that of the placebo group.

Skin infections are another concern. Patients with AE are more prone to skin infections: Staphylococcus aureus and viral infections, including herpes simplex, herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus, molluscum contagiosum, and human papilloma virus.Citation57,Citation58 Skin infections were investigated in 1-year study comparing pimecrolimus and triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream in 658 adults.Citation59 Pimecrolimus was not associated with an increase in bacterial or fungal skin infections, or in herpes simplex or herpes zoster infections compared to triamcinolone. In the pediatric trials, there were no significant differences in overall incidence of skin infections after pimecrolimus treatment in infants or children. In a 2-year open-label trial, the frequency of skin infections did not change over time, as the incidence of skin infections was comparable in the first and second years of treatment. Compared with control treatments, the incidence of all bacterial and viral infections with pimecrolimus in infants treated for more than 1 year was low.Citation60,Citation61 Overall, pimecrolimus cream has demonstrated low systemic absorption and a low incidence of systemic adverse events in children and adults.

Pimecrolimus was issued a black box warning in 2006 due to concerns about incidence of lymphoma. This warning was based on hypothetical concerns about pimecrolimus causing Epstein-Barr virus induced lymphoproliferation disease (lymphoma) or skin cancer. This warning was reviewed by many academic allergy and dermatology societies with the feeling that it was not warranted. The joint task force from the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology and American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology found that the risk-benefit ratio of topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus are similar to that of most conventional therapies for the treatment of chronic relapsing eczema. The panel concluded that

Lymphoma formation is generally associated with high dose and sustained systemic exposure to pimecrolimus and tacrolimus.

The reported cases of lymphoma from topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus are not consistent with lymphomas observed with systemic immunomodulator therapy.

The actual rate of lymphoma formation reported to date for topical calcineurin inhibitors is lower than predicted in the general population.

In large-scale pharmacologic database studies of over 250,000 patients, no increase in the incidence with pimecrolimus was noted for lymphoma.Citation62 The risk of lymphoma does not seem to be an issue for patient using pimecrolimus cream.

Conclusion

Pimecrolimus cream is a safe and effective therapy for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. One of the key components of AE is itch and inflammation. Both elements are relieved within 1 week of pimecrolimus treatment. One of the novel potential uses of pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of AE is the use of proactive therapy. The use of pimecrolimus cream at the first signs and symptoms of AE flare reduces the need for topical steroids. Finally, pimecrolimus cream appears to be safe in both long- and short-term trials with equivalent or superior safety profile to topical corticosteroids.

Disclosures

The author discloses no conflicts of interest.

References

- PeroniDGPiacentiniGLBodiniARigottiEPigozziRBonerALPrevalence and risk factors for atopic dermatitis in preschool childrenBr J Dermatol2008158353954318067476

- SmidesangISaunesMStorroOAtopic dermatitis among 2-year olds; high prevalence, but predominantly mild disease–the PACT study, NorwayPediatr Dermatol2008251131818304146

- KjaerHFEllerEHostAAndersenKEBindslev-JensenCThe prevalence of allergic diseases in an unselected group of 6-year-old children. The DARC birth cohort studyPediatr Allergy Immunol200819873774518318699

- LaughterDIstvanJATofteSJHanifinJMThe prevalence of atopic dermatitis in Oregon schoolchildrenJ Am Acad Dermatol200043464965511004621

- WilliamsHStewartAvonMCooksonWAndersonHIs eczema really on the increase worldwide?J Allergy Clin Immun2008121494795418155278

- SpergelJMPallerASAtopic dermatitis and the atopic marchJ Allergy Clin Immunol20031126 SupplS11812714657842

- PalmerCNIrvineADTerron-KwiatkowskiACommon loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitisNat Genet200638444144616550169

- WeidingerSO’SullivanMIlligTFilaggrin mutations, atopic eczema, hay fever, and asthma in childrenJ Allergy Clin Immunol2008121512031209e120118396323

- BieberTAtopic dermatitisN Engl J Med2008358141483149418385500

- EliasPMHatanoYWilliamsMLBasis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanismsJ Allergy Clin Immunol200812161337134318329087

- ChamlinSLKaoJFriedenIJCeramide-dominant barrier repair lipids alleviate childhood atopic dermatitis: changes in barrier function provide a sensitive indicator of disease activityJ Am Acad Dermatol200247219820812140465

- BacharierLBGehaRSMolecular mechanisms of IgE regulationJ Allergy Clin Immunol20001052 Pt 2S547S55810669540

- HamidQBoguniewiczMLeungDYMDifferential in situ cytokine gene expression in acute versus chronic atopic dermatitisJ Clin Invest1994948708768040343

- HamidQNaseerTMinshallESongYBoguniewiczMLeungDIn vivo expression of IL-12 and IL-13 in atopic dermatitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol1996982252318765838

- LeungDYMAtopic dermatitis: New insights and opportunities for therapeutic interventionJ Allergy Clin Immuno20001055860876

- AkdisMBlaserKAkdisCAT regulatory cells in allergy: novel concepts in the pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment of allergic diseasesJ Allergy Clin Immunol20051165961968 quiz 96916275361

- AkdisCAAkdisMBieberTDiagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology/American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/PRACTALL Consensus ReportAllergy200661896998716867052

- WerfelTBreuerKRole of food allergy in atopic dermatitisCurr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol20044537938515349037

- EigenmannPASichererSHBorkowskiTACohenBASampsonHAPrevalence of IgE-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitisPediatrics19981013E89481027

- SichererSHSampsonHAFood hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis: pathophysiology, epidemiology, diagnosis, and managementJ Allergy Clin Immunol19991043 Pt 2S114S12210482862

- LeverRMacDonaldCWaughPAitchisonTRandomised controlled trial of advice on an egg exclusion diet in young children with atopic eczema and sensitivity to eggsPediatr Allergy Immunol19989113199560837

- WoodmanseeDPChristiansenSCImprovement in atopic dermatitis in infants with the introduction of an elemental formulaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2001108230911496254

- Schmid-GrendelmeierPSimonDSimonHUAkdisCAWuthrichBEpidemiology, clinical features, and immunology of the “intrinsic” (non-IgE-mediated) type of atopic dermatitis (constitutional dermatitis)Allergy200156984184911551248

- WangIJLinYTYangYHCorrelation between age and allergens in pediatric atopic dermatitisAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200493433433815521368

- TuftLHeckVMStudies in atopic dermatitis. IV. Importance of seasonal inhalant allergens, especially ragweedJ Allergy195223652854012990302

- TupkerRADe MonchyJGCoenraadsPJHomanAvan der MeerJBInduction of atopic dermatitis by inhalation of house dust miteJ Allergy Clin Immunol1996975106410708626983

- LeungDYNicklasRALiJTDisease management of atopic dermatitis: an updated practice parameter. Joint Task Force on Practice ParametersAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2004933 Suppl 2S1S2115478395

- HughesJRustinMCorticosteroidsClin Dermatol19971557157219313970

- FurueMTeraoHRikihisaWClinical dose and adverse effects of topical steroids in daily management of atopic dermatitisBr J Dermatol2003148112813312534606

- BodeHHDwarfism following long-term topical corticosteroid therapyJAMA198024488138147392193

- HillCJRostenbergAJrAdverse effects from topical steroidsCutis1978215624628148350

- RaoVUApterAJSteroid phobia and adherence – problems, solutions, impact on benefit/risk profileImmunol Allergy Clin North Am200525358159516054544

- FDAElidel 1% Cream (Pimecrolimus): Packet InsertWashington DCFederal Drug Adminstration2001

- AlaitiSKangSFiedlerVCTacrolimus (FK506) ointment for atopic dermatitis: a phase I study in adults and childrenJ Am Acad Dermatol199838169769448208

- SpergelJMImmunology and treatment of atopic dermatitisAm J Clin Dermatol20089423324418572974

- HultschTKappASpergelJImmunomodulation and safety of topical calcineurin inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitisDermatology2005211217418716088174

- EichenfieldLFThaciDde ProstYPuigLPaulCClinical management of atopic eczema with pimecrolimus cream 1% (Elidel) in paediatric patientsDermatology2007215 Suppl 131718174689

- MeurerMLubbeJKappASchneiderDThe role of pimecrolimus cream 1% (Elidel)) in managing adult atopic eczemaDermatology2007215 Suppl 1182618174690

- KappAPappKBinghamALong-term management of atopic dermatitis in infants with topical pimecrolimus, a nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugJ Allergy Clin Immun2002110227728412170269

- HanifinJThurstonMOmotoMCherillRTofteSGraeberMThe eczema area and severity index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator GroupExp Dermatol2001101111811168575

- EichenfieldLLuckyABoguniewiczMSafety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescentsJ Am Acad Dermatol200246449550411907497

- HoVGuptaAKaufmannRToddGVanaclochaFTakaokaRFolster-HolstRPotterPMarshallKThurstonMBushCCherillRSafety and efficacy of nonsteroid pimecrolimus cream 1% in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in infantsJ Pediatr200314215516212584537

- MeurerMLubbeJKappASchneiderDThe role of pimecrolimus cream 1% (Elidel) in managing adult atopic eczemaDermatology20072151182618174690

- WahnUBosJDGoodfieldMEfficacy and safety of pimecrolimus cream in the long-term management of atopic dermatitis in childrenPediatrics20021101 Pt 1e212093983

- PappKWerfelTFolster-HolstRLong-term control of atopic dermatitis with pimecrolimus cream 1% in infants and young children: a two-year studyJ Am Acad Dermatol20055224024615692468

- HanrahanJChooPCarlsonWGreinederDFaichGPlattRTerfenadine associated ventricular arrhythmias and QTc prolongationAnn Epidemiol1995532012097606309

- MeurerMFartaschMAlbrechtGFor The CASM-DEStudy Group: Long-term efficacy and safety of pimecrolimus cream 1% in adults with moderate atopic dermatitisDermatology200420836537215178928

- KaufmannRBieberTHelgesenALOnset of pruritus relief with pimecrolimus cream 1% in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a randomized trialAllergy20066137538116436149

- LubbeJDegreefHHofmannHClinical use of pimecrolimus cream in atopic eczema: A 6-month open-label trial in 947 patientsJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol2003173183 (abstr 182.139)

- PappKStaabDHarperJEffect of pimecrolimus cream 1% on the long-term course of pediatric atopic dermatitisInt J Dermatol20044397898315569038

- HanifinJGuptaAKRajagopalanRIntermittent dosing of fluticasone propionate cream for reducing the risk of relapse in atopic dermatitis patientsBr J Dermatol2002147352853712207596

- Berth-JonesJDamstraRJGolschSTwice weekly fluticasone propionate added to emollient maintenance treatment to reduce risk of relapse in atopic dermatitis: randomised, double blind, parallel group studyBMJ20033267403136712816824

- BrenemanDFleischerABJrAbramovitsWIntermittent therapy for flare prevention and long-term disease control in stabilized atopic dermatitis: a randomized comparison of 3-times-weekly applications of tacrolimus ointment versus vehicleJ Am Acad Dermatol200858699099918359127

- PallerASEichenfieldLFKirsnerRSShullTJaraczESimpsonELThree times weekly tacrolimus ointment reduces relapse in stabilized atopic dermatitis: a new paradigm for usePediatrics20081226e1210e121819015204

- WollenbergAReitamoSAtzoriFProactive treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults with 0.1% tacrolimus ointmentAllergy2008636742750

- ThaciDReitamoSGonzalez EnsenatMAProactive disease management with 0.03% tacrolimus ointment for children with atopic dermatitis: results of a randomized, multicentre, comparative studyBr J Dermatol200815961348135618782319

- BonifaziEGarofaloLPisaniVMeneghiniCLRole of some infectious agents in atopic dermatitisActa Derm Venereo198511498100

- RystedtIStrannegardILStrannegardORecurrent viral infections in patients with past or present atopic dermatitisBr J Dermatol19861145755823718847

- LugerTLahfaMFolster-HolstRLong-term safety and tolerability of pimecrolimus cream 1% and topical corticosteroids in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitisJ Dermatolog Treat200415110

- PaulCCorkMRossiABPappKABarbierNde ProstYSafety and tolerability of 1% pimecrolimus cream among infants: experience with 1133 patients treated for up to 2 yearsPediatrics2006117e118e12816361223

- EichenfieldLThacibTde ProstcYPuigdLPauleCClinical Management of Atopic Eczema with Pimecrolimus Cream 1% (Elidel®) in Paediatric PatientsDermatology2007215131718174689

- ArellanoFWentworthCEAranaAFernandezCPaulCERisk of lymphoma following exposure to calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids in patients with atopic dermatitisJ Invest Dermatol200712780881617096020

- HanifinJRajkaGDiagnostic features of atopic dermatitisActa Derm Venereol1980924447

- GollnickHKaufmannRStoughDPimecrolimus cream 1% in the long-term management of adult atopic dermatitis: prevention of flare progression. A randomized controlled trialBr J Dermatol200815851083109318341665

- MeurerMFolster-HolstRWozelGWeidingerGJungerMBrautigamMPimecrolimus cream in the long-term management of atopic dermatitis in adults: a six-month studyDermatology2002205327127712399676