Abstract

Much evidence on the favorable effects of omega-3 ethyl esters on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality has been obtained in studies performed in healthy subjects and in different clinical settings. Here the clinical effects of omega-3 ethyl ester administration in patients with previous myocardial infarction or heart failure are reviewed, together with a discussion of underlying mechanisms of action. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of omega-3 ethyl esters, as well as evidence concerning their safety and tolerability, are also reported.

Introduction

Since the first evidence showing a protective effect against coronary artery disease (CAD), reported more than 30 years ago,Citation1,Citation2 several epidemiologic and clinical studies have indicated an inverse relationship between a diet rich in fish and cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality.Citation3–Citation8 Two compounds of the omega-3 fatty acid class, namely eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), were presumed to be the active ingredients in fish.Citation9 In the early 1980s, a large-scale method to purify EPA and DHA in the chemical form of an ethyl ester (EE) was developed for clinical use. Since then, several studies have investigated the role of isolated and combined EPA and DHA in the form of EE, especially with respect to CV disease prevention. Overall the results of these studies indicated a protective effect of omega-3 EE on total mortality and CV events.

In many European countries, oral omega-3 EE administration is indicated in adult patients for secondary prevention after myocardial infarction (MI) and for the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia. In the US, omega-3 EE prescription is indicated for the treatment of triglyceride (TG) levels ≥500 mg/dL.

The purpose of this article is to review the pharmacologic properties of oral omega-3 EE, describing briefly the evidence for omega-3 EE and hypertriglyceridemia, and focusing attention on their efficacy and tolerability in secondary prevention after MI and in patients with heart failure (HF).

Triglycerides and cardiovascular risk

Evidence from observational and experimental studies suggests a relationship between triglycerides (TG) and CV disease.Citation10–Citation13 In the female population of the Framingham study, there was an increase in CV event rates as TG levels increased. In men the correlation was not evident, although there was a 40% increase in incidence of coronary events as TG increased up to 200 mg/dL, without a further increase of risk at higher levels.Citation10

Findings from the Münster Heart Study (PROCAM) showed that coronary event rates increased as TG levels increased from <200 mg/dL to 800 mg/dL, but decreased significantly above this level.Citation11 When TG levels were evaluated as a continuous variable, their level was not correlated with event rates. This finding likely reflects different atherogenicity of TG-rich lipoproteins at different TG levels; at the highest TG levels (>800 mg/dL), less atherogenic chylomicrons predominate compared with the more atherogenic ones predominating in subjects with TG <800 mg/dL. Austin et al reported the existence of two low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) phenotypic distributions in relation to TG levels, ie, a less atherogenic phenotype A, characterized by large buoyant LDL particles that predominate with low TG levels, and a highly atherogenic phenotype B represented by small dense LDL particles that is prevalent with increased plasma levels of TG.Citation14

The Baltimore Coronary Observational Long-Term Study was a long-term (20-year) study that evaluated predictors of coronary events in individuals who had documented CAD.Citation13 TG, as well as diabetes mellitus, were found to be important predictors, with a TG level >100 mg/dL increasing the risk for coronary events by 50% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1–2.1). After exclusion of diabetic patients, TG remained a significant predictor of new CAD events (relative risk [RR] 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2–2.7).

The combined effect of baseline TG and lipoprotein cholesterol levels on the incidence of CV endpoints was studied in the Helsinki Heart Trial. After five years of follow-up, the combination of LDL-C to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) ratio >5 with TG >200 mg/dL revealed a subgroup of subjects at high CV risk (RR 3.8, 95% CI: 2.2–6.6).Citation15 Some clinical studies, but not all, reported a reduction of the risk of CV events by treatment with a fibric acid derivate in patients with high TG.

In patients with documented CAD, the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention trial (BIP) tested the effect of bezafibrate (400 mg/day) on a combined endpoint including death from CAD or nonfatal MI.Citation16 The primary endpoint in BIP was not affected by fibrate therapy, although it induced a significant 15.4% increase in HDL-C, and a significant 6.2% decrease in LDL-C. However, when data from the subset of patients with baseline TG >200 mg/dL were analyzed, a significant 40% reduction in the primary endpoint was observed.Citation16

At variance with previous studies, the benefit reported in the Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention trial (VA-HIT) did not appear to be correlated with TG reduction.Citation17 In patients with CAD, there was an overall 22% reduction in the rates for fatal and nonfatal MI or death from CAD in subjects randomized to gemfibrozil. However, multiple regression analyses failed to find a consistent link between TG and CAD event rates for all levels of TG.Citation17,Citation18

More recently, a post hoc analysis of PROVE IT-TIMI 22, a study which compared the effects of standard versus intensive statin therapy on the incidence of CV events in patients hospitalized for an acute coronary syndrome (ACS), evaluated the relationship at 30 days between on-treatment TG levels, LDL-C, and a composite endpoint of death, MI, and recurrent ACS.Citation12 On-treatment TG <150 mg/dL was independently associated with a lower risk of recurrent CHD events (adjusted hazards ratio [HR] 0.80, 95% CI: 0.66–0.97, P = 0.025). For each 10 mg/dL decrement in TG the risk of the composite endpoint was lowered by 1.6% (P < 0.001) after adjustment for LDL-C. These results supported the concept that achieving low TG, beyond low LDL-C, may deserve additional consideration in patients after ACS.

Cardioprotective effects of omega-3 ethyl esters

Since the first evidence of a protective effect on CAD, many studies of fish intake or daily administration of fish oils have reported an inverse relationship with CV morbidity and mortality.Citation3–Citation8,Citation19

In the early 1980s, EPA and DHA became available for clinical use in the purified chemical form of EE. Each 1000 mg capsule of omega-3 EE contains approximately 460 mg of EPA EE and 380 mg of DHA EE.Citation20 Oral capsules of omega-3 EE, although providing fewer nutritional elements than fish, have the advantage of avoiding the possible negative effects of contaminants contained in fish (eg, dioxins, mercury, and polychlorinated biphenyls),Citation21,Citation22 the different action of various concentrations of EPA and DHA, and finally the effects of other fatty acids usually contained in fish oils. Since the commercialization of omega-3 EE, several studies have investigated isolated and combined preparations of EPA and DHA in the form of EE, especially with respect to CV prevention. Taken together, the results of the more recent studies confirmed that omega-3 fatty acids have cardioprotective effects,Citation8,Citation19,Citation23–Citation27 with an inverse correlation between risk of CAD events and quantity of DHA in plasma and cellular phospholipids, which is closely linked to the DHA content of the myocardium.Citation28

Oral omega-3 EE is able to improve the lipid profile principally by reducing TG levels. However, in the major studies, changes in TC and HDL-C were generally not clinically significant, with a small net increase in LDL-C associated with a shift toward less atherogenic LDL subfractions.

In patients with previous MI, the addition to recommended treatment (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, antiplatelet agents, β-blockers, statins) of oral omega-3 EE 1000 mg/day was effective for secondary prevention, reducing the risk of the composite endpoint of death + nonfatal MI + nonfatal stroke as well as various other endpoints (including death, CV death, and sudden death).Citation23,Citation29 Post hoc results of analysis of individual events in the composite endpoint, as well as the time-course assessment of benefit of omega-3 EE, suggest that the reduction in the risk of fatal events following omega-3 EE contribute importantly to the significant reductions observed in the risk of the composite efficacy endpoints. The 45% reduction in the risk of sudden death was the major component in the reduction in risk of death shown in GISSI-Prevenzione.

The recent publication of the GISSI-HF trial resultsCitation26 confirmed previous less consistent evidenceCitation30–Citation33 about a possible benefit of omega-3 EE in patients with HF. After a median follow-up of 3.9 years, 850–882 mg daily of EPA and DHA as EE induced a statistically significant risk reduction in mortality and mortality + admission to hospital for a CV reason. Almost half of the absolute reduction of risk attributable to treatment was due to the reduction of ventricular arrhythmias, although the benefit in both mortality and hospitalization suggests that omega-3 EE might also positively affect the pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to the progression of HF.

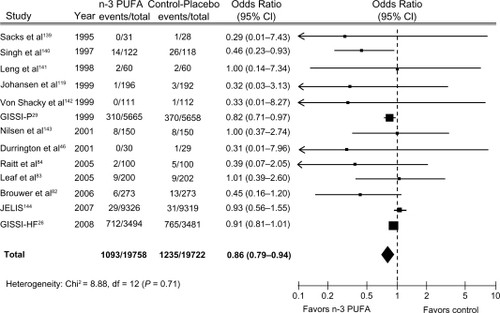

Despite the results of many studies indicating cardioprotective effects of omega-3 fatty acids, a Cochrane reviewCitation34 and a meta-analysisCitation35 seem not to confirm these benefits. The Cochrane review,Citation34 which included 89 studies (48 randomized controlled studies and 41 cohort studies), found that omega-3 EE did not induce a significant reduction in the risk of total mortality (RR 0.87; 95% CI: 0.73–1.03) or combined CV events (RR 0.95; 95% CI: 0.82–1.12). The choice of inclusion of the DART (Diet and Reinfarction Trial) II in the analysis has generated considerable debate.Citation27,Citation36,Citation37 After excluding DART II from the Cochrane analysis, the reduction of total death became statistically significant (RR 0.83; 95% CI: 0.75–0.91), but the risk of CV events did not change.Citation34 We updated the metanalysis of Leon et alCitation38 including two recent clinical trials, GISSI-HF and OMEGA trial. We found that Omega-3 EE was associated with a 14% (OR 0.86; 95% CI 0.79–0.94) significant risk reduction of death from cardiac cause and with barely not statistically significant risk reduction of all cause mortality (odds ratio [OR] 0.92; 95% CI: 0.83–1.03) (), confirming findings reported by Leon et al.Citation38 Of note, the beneficial effects on risk of CV disease (CVD) appeared strong in the analysis of trials of secondary prevention, but not in those of the primary one.Citation39 This finding should be considered against the efficacy of omega-3 fatty acids in primary CVD prevention. In fact, only 50% of the causes of death are usually due to CVD in this clinical setting and are therefore potentially modifiable by omega-3 fatty acids. However, this finding, and the higher proportion of deaths due to CV causes in patients with CVD, translate into very different benefits on total mortality in patients with or without CVD.

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetic properties

Oral administration of omega-3 EE to healthy volunteersCitation40–Citation42 and hypertriglyceridemic subjectsCitation42 is followed by EPA and DHA absorption. After a first complete hydrolysis of omega-3 EE, EPA and DHA are absorbed and incorporated into plasma phospholipids and cholesterol esters, as reported in animal studies.Citation20 Omega-3 EE oral administration in healthy volunteers for 12 weeks determined significant dose-dependent increases in plasma phospholipid EPA and DHA content.Citation43 The same increases in plasma/serum phospholipid EPA and DHA content were seen in various patient populations receiving oral omega-3 EE, such as those with combined hyperlipidemia,Citation44 severe hypertriglyceridemia,Citation45 CAD,Citation46 essential hypertension,Citation47 and hypertensive heart transplant recipients.Citation48

EPA and DHA concentrations in plasma phospholipids are related to the level of EPA and DHA incorporated into cell membranes.Citation20 Omega-3 fatty acids are metabolized via three main pathways. Fatty acids are first transported to the liver for incorporation into lipoproteins, and then channeled to peripheral lipid stores. Secondly, cell membrane phospholipids are replaced by lipoprotein phospholipids, allowing EPA to act as a precursor for eicosanoids of the cyclo-oxygenase and lipoxygenase pathways.Citation20,Citation24,Citation49 Finally, omega-3 fatty acids, like all other fatty acids, are oxidized to meet energy requirements.Citation20,Citation24 Uptake of EPA and DHA into serum phospholipids in recipients of omega-3 EE concentrate was independent of age (<49 versus ≥49 years), and tended to be greater in women than in men.Citation42

In healthy volunteers, the concomitant administration of omega-3 EE concentrate did not alter the steady-state pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin (and its major active metabolites, 2-hydroxyatorvastatin and 4-hydroxyatorvastatin),Citation50 rosuvastatin,Citation51 and simvastatin (and its major active metabolite, β-hydroxysimvastatin).Citation52 To support these findings, experimental studies showed that undetectable concentrations (<1 μmol/L) of the free forms of EPA and DHA are present in the circulation, so avoiding clinically significant inhibition of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.Citation42

Pharmacodynamic properties

Although the mechanism of action of omega-3 fatty acids, including omega-3 EE, is not fully understood,Citation40,Citation42 a number of effects of omega-3 EE that can positively interfere with the development or worsening of CV disease have been reported. Available evidence seems to suggest that EPA and DHA might differ in the mechanisms by which they exert their beneficial effect on the CV system. This hypothesis needs to be carefully assessed and confirmed.Citation53 In this review we discuss mechanisms which are likely to contribute to the benefit of omega-3 EE in post-MI and HF patients, including effects on lipid levels, cardiac electrophysiology and hemodynamics, blood pressure, endothelial function, thrombosis/homeostasis, and atherogenesis and inflammation.

Lipid levels

Omega-3 EE improved the lipid profile in patients with mixed dyslipidemia,Citation54 familial combined hyperlipidemia,Citation55 and hypertriglyceridemia.Citation56–Citation59 Significant reductions in TG, total cholesterol, non-HDL-C, very LDL-C (VLDL-C), VLDL-triglyceride and/or apoliprotein-B levels, and significant elevation in plasma or serum HDL-C and/or LDL-C levels with omega-3 EE 4000 mg/day, aloneCitation56–Citation59 or in combination with simvastatin 40 mg/dayCitation54 were evident.

Similar data were reported in a review that demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction in TG levels in clinical studies.Citation60 In most studies, a 10%–33% reduction in TG levels was seen, that tended to be greater in studies of patients with higher TG levels at baseline. Total cholesterol and HDL-C did not significantly change, whilst a slight increase in LDL-C levels occurred.Citation60

Omega-3 EEs exert a triglyceride-lowering effect through two main mechanisms.Citation40 Firstly omega-3 EE may reduce the hepatic synthesis of TG inhibiting acyl CoA:1,2-diacylglycerol acyltransferase,Citation61 with reduced esterification and release of other fatty acids.Citation20,Citation61 Secondly, omega-3 EEs increase hepatic β-oxidation and upregulate fatty acid metabolism in the liver by stimulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) subtypes.Citation62–Citation64 This in turn reduces the availability of free fatty acids for TG synthesis and reduces TG levels.Citation20 Omega-3 EE also affects other nuclear receptors involved in the modulation of TG levels, so they may increase the removal of TG from circulating VLDL via enzymatic upregulation.Citation65

The elevation in LDL-C levels observed with omega-3 EE seems to result from conversion of VLDL-C.Citation66 In a study of 24 dyslipidemic obese patients, treatment with omega-3 EE 4000 mg/day significantly increased the mean conversion rate of VLDL-apoliprotein B to intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL)-apoliprotein B and LDL-apoliprotein B, as well as the mean conversion rate of IDL-apoliprotein B to LDL-apoliprotein B.Citation67 Of note, the observed increase in LDL-C levels typically reflects a shift to larger, less atherogenic LDL particles.Citation68 In patients with hypertriglyceridemia, despite the treatment with simvastatin 40 mg/day, those randomized to receive omega-3 EE 4000 mg/day for eight weeks showed a significantly greater median LDL particle size increase than patients on placebo. The direction of the shift in LDL particle size seemed to depend on the TG level; median changes in LDL particle size from baseline were +0.60, +0.40, +0.15, and −0.20 nm in patients with on-treatment TG levels of <149, 149–192, 193–246, and ≥246 mg/dL, respectively. In the same subgroups of patients, LDL subfraction pattern B (ie, smaller particles) was present in 68%, 79%, 93%, and 73% of patients at endpoint.Citation69 Similar results were observed in a studyCitation54 conducted in patients with mixed hyperlipidemia, ie, omega-3 EE 4000 mg/day + simvastatin 20 mg/day induced a significant (P < 0.05) increase from baseline in least-square mean LDL particle size compared with placebo + simvastatin 20 mg/day, with no between-group difference in LDL particle concentration. Significantly greater reductions from baseline in VLDL particle size and concentration were also observed between the two treatment groups. Both omega-3 EE 4000 mg/day and oral gemfibrozil 1200 mg/day improved the atherogenic LDL subfraction profile of patients with hypertriglyceridemia, elevating the cholesterol content of the more buoyant, less atherogenic LDL-1, LDL-2, and LDL-3 subfractions versus baseline. No significant differences in the LDL-4 and LDL-5 subfractions versus baseline and no between-group differences in the cholesterol levels of the LDL subfractions were observed.Citation59 In patients with familial combined hyperlipidemia, omega-3 EE treatment increased the LDL-C/apoliprotein-B ratio, indicating an elevation in the more buoyant and core-enriched LDL-1 and LDL-2 subfractions, although the average LDL particle size was unchanged.Citation55

Cardiac electrophysiology

Heart rate

According to the results of a meta-analysis,Citation70 omega-3 fatty acids (median dosage 3500 mg/day), significantly reduced heart rate by 1.6 beats per minute compared with placebo. Subgroup analysis showed this effect to be influenced by baseline heart rate; in patients with a mean heart rate ≥69 beats per minute at baseline there was a significant (P < 0.001) reduction of 2.5 beats per minute, with no significant change in patients with a mean heart rate of <69 beats per minute at baseline.Citation70

Arrhythmias

The antiarrhythmic effect is believed to be the main mechanism explaining the reduced risk of sudden cardiac death seen in patients with recent MI treated with omega-3 EE in the GISSI-Prevenzione study.Citation23 This apparent antiarrhythmic effect may result from a number of mechanisms.

Experimental evidence suggests that n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) administered in the diet, added to culture media, or given intravenously, have direct effects on the trafficking of ion channels in cardiac membranes which may result in antiarrhythmic activity.Citation71 The peculiarity of this action is that n-3 PUFA are likely to have a number of effects which could be pro- as well as antiarrhythmic. The sum of all these activities in modulating the electrical machinery of cardiac cells produces a positive “final” effect on life-threatening arrhythmias. The current hypothesis is that omega-3 EEs stabilize the electrical activity of myocytes by elevating the action potential threshold (ie, a stronger electrical stimulus is required to elicit an action potential), shortening the action potential duration, and prolonging the relative refractory time. The major contributors to the antiarrhythmic actions of omega-3 EE occur via inhibition of the voltage-dependent Na+ currents, which initiate the action potential in excitable tissue. The beginning of the action potential may be also avoided, reducing delayed afterdepolarization through an inhibition of L-type Ca++ currents which prevent Ca++ overload. n-3 PUFA have also been reported to inhibit some potassium current components, such as the two repolarizing K+ currents, the initial outward K+ (Ito) current, and the delayed rectifier K+ (IK) current, as well as the transient outward current responsible for the early repolarization phase. n-3 PUFA have been found to have an inhibitory effect on the cardiac Na+/Ca++ exchange (NCX) current. NCX protein expression in its forward mode (INCX) provides a mechanism for extruding calcium from the cytosol and facilitates diastolic relaxation, and is often increased in patients with end-stage HF and with atrial fibrillation (AF).Citation72 Decreased INCX may therefore result in a decreased propensity to develop delayed after depolarization and may contribute to the antiarrhythmic effects of n-3 PUFA.

The inhibition of intercellular communication may represent an additional potential antiarrhythmic mechanism of n-3 PUFA. Treatment with n-3 PUFA reduced vulnerability to induction of AF in a dog model by reducing atrial expression of connexin.Citation73

Furthermore, a cell membrane shift in the balance of n-3 PUFA to n-6 PUFA might attenuate the production of n-6 PUFA-derived eicosanoids, including thromboxane A2 and prostaglandins, which have been suggested to promote arrhythmias.Citation74,Citation75

Finally, omega-3 EEs may reduce arrhythmic events modulating autonomic tone.Citation25,Citation76 This hypothesis seems to be corroborated by some studies on heart rate variability (HRV), a risk marker for sudden cardiac death. Omega-3 fatty acids content of cell membranes was positively correlated with HRV,Citation77 and oral supplementation with 5200 mg/day of omega-3 fatty acids for three months in patients with recent MI significantly increased HRV.Citation78 In patients with healed MI and left ventricular dysfunction, omega-3 fatty acids 1500 mg/day significantly improved HRV in the high-frequency band, compared with placebo, although there was no improvement in overall HRV.Citation79 At variance with the previous evidence are the results of two studies showing that omega-3 EE at a daily dose of 1000 mg for three months in patients with mild hypertensionCitation80 and of 3000 mg for four months in post-MI patients,Citation81 did not alter HRV indices to a significant extent.

Some recent studies in patients with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) reported mixed results for an antiarrhythmic effect of omega-3 EE.Citation82–Citation84 Primary endpoints relating to the risk of ventricular arrhythmias ICD intervention for ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardiaCitation82–Citation84 or deathCitation82,Citation83 were not improved by omega-3 EE to a significant extent. But when “probable” ventricular arrhythmic events were also considered, a significant 31% reduction in the primary endpoint was seen with omega-3 EE.Citation83

It has been hypothesized that omega-3 fatty acids may have more favorable effects in certain subpopulations, in which the specific clinical setting and underlying arrhythmogenic mechanisms of initiation and propagation may be more susceptible to the antiarrhythmic effects of omega-3 EE. It should be noted, for example, that patients enrolled in ICD trials were different from those in GISSI-Prevenzione.Citation23 The best evidence for the antiarrhythmic action of n-3 PUFA has been produced by experimental work performed in ischemia-mediated animal models and in clinical trials carried out in post-MI patients in which ischemia-triggered arrhythmias may be predominant.

In addition, chronic oral dosing of omega-3 fatty acids, compared with acute or intravenous administration, may have different effects on cardiac electrophysiology, as suggested by experimental data showing that incorporation of n-3 PUFA into membrane phospholipids shortened the action potential without altering calcium transients and diastolic calcium levels in myocytes isolated from pigs.Citation72 It has been hypothesized that tissue levels of n-3 PUFA may influence the effects of oral administration of omega-3 EE; low basal tissue levels consequent to a daily intake <750 mg might amplify the antiarrhythmic effect of omega-3 EE supplements, with a first steep slope of the dose-response curve and a plateau thereafter, with no further beneficial effects on fatal arrhythmic events with higher doses.Citation22 Such a hypothesis would explain the high protective effect of omega-3 EE against arrhythmic death in patients with low dietary intake of n-3 PUFA and HFCitation26 or ischemic heart disease.Citation23,Citation29

Cardiac hemodynamics

Cardiac function

Evidence suggests an improvement of cardiac output with omega-3 EE supplements by means of a positive action on systolic and diastolic function. Experimental evidence of a faster rate of cardiac muscle contraction and relaxation by n-3 PUFA with a consequent positive inotropic effect has been reported.Citation85 In addition, EPA and DHA may prevent the myosin heavy chain isoform α to β switch, a marker of HF and left ventricular hypertrophy.Citation86

Results of the Cardiovascular Health StudyCitation87 seem to confirm in older adults the findings previously shown in nonhuman primatesCitation88 of an association between fish intake and incremental stroke volume due to improvement of early and, possibly, late diastolic filling. Recently, chronic n-3 PUFA administration in athletes has been reported to reduce heart rate and oxygen consumption during exercise without a decrement in performance, in part due to improved energy production and utilization by cardiac myocytes.Citation89

Experimental data showed an increase in efficiency of oxygen use by the heart and skeletal muscles after n-3 PUFA supplementation, possibly through improvement in mitochondrial function and efficiency of ATP generation.Citation90,Citation91

EPA and DHA was shown to be able to modify mitochondrial membrane properties, activate PPAR, and increase expression of metabolic enzymes, such as those involved in fatty acid oxidation and energy transduction, so preventing the increase in left ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes in a rat model of pressure overload.Citation86

Blood pressure

According to the results of a meta-regression analysis, omega-3 fatty acid administration at a mean dosage of 4100 mg/day was able to decrease mean blood pressure (BP) by 2.3/1.5 mmHg.Citation92 Subgroup analyses demonstrated that BP was reduced to a greater extent in older (age >45 years) versus younger participants and in hypertensive versus normotensive participants.

The findings of this meta-regression analysis were supported by studies in patients with essential hypertension,Citation47,Citation93 hypertriglyceridemia,Citation57 or combined hyperlipidemia,Citation44,Citation94 patients who had undergone heart transplantation,Citation95 or hypertensive heart transplant recipients,Citation48 showing significant reductions in systolic and/or diastolic BP with omega-3 EE given at 2000–6000 mg/day. The reduction of BP may be due to effects on the arterial vascular bed. Improvement of endothelial dysfunction,Citation96 reduction of systemic vascular resistanceCitation87 possibly by induction of nitric oxide production,Citation97 reduction of vasoconstrictive response to norepinephrine and angiotensin II,Citation98 improvement of arterial wall compliance,Citation99 and enhancement of vasodilatory responsesCitation98 have been reported.

On the other side, some studies reported no evidence of effects of omega-3 EE on BP at doses of 1000 mg/day in post-MI patients,Citation80 3000 mg/day in patients with mild hypertension,Citation81 or 4000 mg/day of omega-3 EE in healthy volunteers.Citation100

Endothelial function

A critical balance between endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors maintains vascular homeostasis and vascular smooth muscle tone. The endothelium, by releasing nitric oxide (NO), promotes vasodilatation and inhibits inflammation, thrombosis, and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. In addition, NO opposes the actions of potent endothelium-derived contracting factors such as angiotensin-II and endothelin-1 (ET-1). Endothelial dysfunction is a pathologic state in which there is an imbalance in the relative contribution of endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors (such as ET-1, angiotensin, and oxidants). Endothelial dysfunction plays an important role in the clinical course of atherosclerosis. Common conditions predisposing to atherosclerosis, such as hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking, are associated with endothelial dysfunction.

A small number of studies found endothelial function to be improved after fish oil ingestion by humans.Citation8 In patients with hypercholesterolemia, baseline endothelium-dependent flow-mediated dilatation increased to a significantly greater extent with omega-3 EE 4000 mg/day than with placebo without affecting endothelium-independent dilation.Citation101 In a six-week, randomized crossover trial, 20 children with familial (combined) hyperlipidemia received DHA 1200 mg/day. Endothelial function improved in this study, although levels of total cholesterol, LDL, and HDL increased, compared with subjects receiving the National Cholesterol Education Panel (NCEP)-II diet during the control period.Citation102 In a randomized, double-blind study comparing 4000 mg/day EPA with 4000 mg/day DHA and with 4000 mg/day olive oil (control) in 59 overweight, mildly hyperlipidemic men, DHA, but not EPA, improved the response to acetylcholine. DHA, however, improved the response to sodium nitroprusside and attenuated the constrictive response to norepinephrine, whilst olive oil had no effect.Citation98 More recently, improvements in endothelial function have been reported in patients receiving omega-3 fatty acids.Citation68 Thus the available evidence indicates that EPA-DHA improves endothelial function in patients with CV disorders. When EPA and DHA were compared, only DHA, but not EPA, was found to be effective.

Thrombosis and hemostasis

In vitro studies have shown that omega-3 fatty acids have inhibitory effects on thrombosis through reduction of platelet aggregation,Citation103–Citation105 and platelet thromboxane B2 response,Citation105 thus suggesting a potential cardioprotective effect through antithrombotic mechanisms.Citation21 In healthy volunteers receiving omega-3 EE 1000–4000 mg/day, EPA was incorporated into platelets in a dose-dependent manner.Citation43

Platelet-activating factor (an inducer of platelet aggregation) was reduced by 900 mg/day EPA given for eight weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, the effect being more pronounced after doubling the daily dose.Citation106 In a six-week randomized, double-blind study, 4000 mg/day of EPA and 4000 mg/day DHA were compared with olive oil in 59 hypertensive type 2 diabetics. DHA, but not EPA, reduced platelet response to collagen and associated thromboxane A2 formation, without differences in other parameters such as fibrinolytic activity.Citation107 In patients with CAD, fibrinolytic activity, as assessed by plasminogen activator inhibitor-I activity levels, was found to be increased by 1800 mg/day of EPA,Citation108 and by EPA–DHA 3400 mg/day.Citation109 A three-month randomized study comparing 850 mg/EPA-DHA with usual care in 77 post-MI patients showed no differences in levels of fibrinogen or D-dimer, although von Willebrand factor was increased.Citation110 Across clinical studies, omega-3 fatty acids did not show a consistent effect on hemostatic variables including levels of fibrinogen, factor VII or VIII or von Willebrand factor.Citation60,Citation111 Moreover, changes in levels of fibrinogen, factor VII or VIII, or von Willebrand factor generally did not significantly differ between recipients of 1000–6000 mg/day omega-3 EE and controls in healthy volunteers,Citation112 post-MI patients,Citation110 patients with mild hypertension,Citation81 patients with combined hyperlipidemiaCitation109 or patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.Citation113

Bleeding time was prolonged in 40 post-MI patients after four weeks of 3400 mg/day EPA-DHA, without significant alteration of other hemostatic parameters,Citation114 and increased in one study in CAD patients.Citation115 At variance with previous studies, omega-3 EE 6000 mg/day did not affect bleeding time at rest in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia,Citation100,Citation113 or in patients undergoing CABG surgery.Citation113 In addition, the incidence of bleeding episodes did not significantly differ between omega-3 EE 4000 mg/day and placebo recipients in a large study in patients undergoing CABG surgery who were also receiving warfarin or aspirin.Citation116 This finding is reassuring with regard to the current clinical relevance of the concern raised by older studies testing very high omega-3 fatty acid doses about a potential increased risk of bleeding due to the antithrombotic effect of omega-3 fatty acids.Citation21,Citation117

However, hemocoagulatory tests should be performed to monitor adequately patients receiving anticoagulant therapy and the anticoagulant dosage adjusted as necessary.Citation20

Atherogenesis and inflammation

Many effects of n-3 PUFA may positively interfere with atherosclerotic processes. Other than improvement in lipid levels, the effects on cell adhesion molecules, receptor scavenger expression, and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation may reduce development of atherosclerotic lesions.Citation118 Although treatment for six months with omega-3 EE 6000 mg/day did not reduce the incidence of restenosis in patients who had undergone coronary angioplasty,Citation119 two meta-analyses suggested that omega-3 fatty acids may indeed prevent restenosis following this procedure.Citation120,Citation121 In patients with planned carotid endarterectomy, administration of 2000 mg/day of omega-3 EE significantly increased plaque phospholipid EPA content compared with placebo.Citation78 The potential improvement of plaque stability consequent to the increase of EPA and DHACitation122 was based on the finding that plaques from patients receiving omega-3 EE expressed significantly lower mRNA levels for matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-7, MMP-9, MMP-12, and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 than did plaque from placebo recipients.Citation78 Omega-3 EE 4000 mg/day after six weeks’ therapy increased soluble E-selectin levels from baseline to a significantly greater extent than did placebo in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. However, after more than six months’ treatment, significant decreases in soluble E-selectin levels and in soluble ICAM-1 levels were observed.Citation56 Gene expression of platelet-derived growth factors A and B was downregulated in mononuclear cells from healthy volunteers who received omega-3 EE 7000 mg/day for six weeks.Citation123 Endotoxin-stimulated tumor necrosis factor-α production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells was significantly reduced from baseline in patients with severe HF who received omega-3 fatty acids 8000 mg/day for 18 weeks.Citation124 It has been recently reported that the beneficial effects of n-3 fatty acid supplementation on inflammatory processes may be due to an increase in EPA-derived eicosanoids, PGE3 and LTB5, which are less active in the inflammatory response than AA-derived eicosanoids (PGE2 and LTB4).Citation125

At variance with the above, some evidence did not report an improvement of inflammatory markers. C-reactive protein levels were not affected by treatment with omega-3 fatty acids.Citation60,Citation79 Compared with olive oil-treated controls, C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α were unaltered in 59 hypertensive Type 2 diabetics treated for six weeks with 4000 mg/ day of EPA or DHA.Citation126 In post-MI patients treated with omega-3 EE 1000 mg/day, interleukin-6 levels were not modified to a significant extent compared with controls.Citation110 Finally, the effect of n-3 PUFA on oxidative stress remains controversial.Citation118,Citation126,Citation127

Clinical efficacy

After myocardial infarction

GISSI-Prevenzione was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial that assessed the comparative efficacy of omega-3 EE, as monotherapy or in combination with tocopherol, versus tocopherol monotherapy or control (no treatment) as secondary prevention for post-MI patients.Citation23,Citation128 From October 1993 to September 1998, 11,323 patients who had suffered an MI within the previous three months (median 16 days) were randomized to receive omega-3 EE 1000 mg/day (n = 2835), omega-3 EE 1000 mg/day + tocopherol 300 mg/day (n = 2830), tocopherol 300 mg/day (n = 2830), or control (n = 2828) for 42 months. The patients’ mean age was 59.4 years, with 16% aged >70 years, and 85.3% were male. At baseline, an ejection fraction of ≤30% and 0.31–0.40 was present in 2.6% and 11.1% of patients, respectively; 42.4% of patients were smokers, 35.6% were diagnosed with arterial hypertension, 4.4% had claudication, 14.8% had diabetes mellitus, 19.3% had ventricular arrhythmias, and 28.9% had a positive exercise stress test. Mediterranean dietary advices were given to all patients. Investigators were required to prescribe post-MI evidence-based therapy at baseline as well during the course of the study. At baseline, ACE inhibitors, antiplatelet agents, β-blockers, and lipid-lowering drugs were prescribed to 46.9%, 91.7%, 44.3%, and 4.7% of patients, respectively. The proportion of patients receiving the aforementioned medical treatments did not change much during the course of the study, but lipid-lowering treatments were prescribed to more than 30% of patients after six months and, at the end of the study, approximately 50% of patients was treated with statins.

The primary combined efficacy endpoints for the GISSI-Prevenzione study were the cumulative rate of all-cause death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke, and the cumulative rates of CV death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke. Secondary endpoints included the individual components of the primary endpoints and the major causes of death.

The efficacy of the experimental treatments was compared by two prespecified intention-to-treat analyses over 42 months of follow-up. A four-way analysis of data compared the efficacy of omega-3 EE monotherapy, tocopherol monotherapy, and omega-3 EE + tocopherol with that of the control over the same time period; the efficacy of omega-3 EE + tocopherol was also compared with omega-3 EE monotherapy and tocopherol monotherapy. A two-way factorial analysis compared omega-3 EE-based therapy (omega-3 EE monotherapy and omega-3 EE + tocopherol groups) with that of non-omega-3 EE-based therapy (tocopherol monotherapy and control groups) and the efficacy of tocopherol-based therapy (tocopherol monotherapy and omega-3 EE + tocopherol groups) versus non-tocopherol-based therapy (omega-3 EE monotherapy and control).

The results of GISSI-Prevenzione showed that omega-3 EE had a secondary preventive effect in patients with recent MI. The full efficacy profile of omega-3 EE is summarized in .

Table 1 GISSI-Prevenzione. Overall efficacy profile of n-3 PUFA, vitamin E, and n-3 PUFA + vitamin E treatment

In the four-way analysis there were significant reductions of both coprimary endpoints, ie, a 16% relative risk decrease for the combined endpoint of death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (95% CI 3–27, P = 0.02) and a 20% relative risk decrease for the secondary combined endpoint of CV death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (95% CI 6–32, P = 0.006). Analyses of the individual components of the main endpoint were instrumental in speculation as to the mechanism of action of omega-3 EE. Almost all the benefit obtained with omega-3 EE in the combined endpoint was due to the decrease in fatal events (−21% of total deaths, −30% of CV deaths, and −44% of sudden deaths), suggesting that antiarrhythmic effect is the probable mechanism of action of omega-3 EE. With regard to nonfatal CV events, there was no significant difference between the treatment groups, and the results for the combined treatment compared with controls on the primary combined endpoint and on total mortality were consistent with those obtained with omega-3 EE alone. No increased benefit was apparent when the rate of the combined endpoint of death, nonfatal MI and nonfatal stroke among patients receiving omega-3 EE + vitamin E was compared with that of the group receiving omega-3 EE alone or with that of patients treated with vitamin E alone. Patients receiving vitamin E and controls did not differ significantly when data were analyzed for the combined endpoint as well as for its individual components. Treatment with omega-3 EE alone significantly lowered the risk of total CHD events (0.78 [0.65–0.94], P = 0.008), whereas the reduction of risk observed with vitamin E was not statistically significant. No change in fatal + nonfatal stroke was found for any tested treatment. The results of the two-way analysis adjusted for interaction between the treatments were exactly the same as the results of the four-way analyses, with the interaction being statistically significant for CV, cardiac, and sudden death, and statistically relevant (P < 0.10) for the second main endpoint and all CHD events ().

At six months, a significant reduction in TG levels was observed, but no clinically relevant change from baseline was shown for total cholesterol, LDL-C and HDL-C levels, fibrinogen, and glycemia.

A post hoc analysis of GISSI-PrevenzioneCitation29 assessed the time course of the benefit of omega-3 EE on mortality and supported the hypothesis of an antiarrhythmic effect of omega-3 EE. Survival curves for n-3 PUFA treatment diverged early after randomization, and total mortality was significantly lowered after only three months of treatment (RR 0.59; 95% CI 0.36–0.97; P = 0.037). The reduction in risk of sudden death was specifically relevant and statistically significant already at four months (RR 0.47; 95% CI 0.219–0.995; P = 0.048). A similarly significant, although delayed, pattern after six to eight months of treatment was observed for CV, cardiac, and coronary deaths.

Another post hoc analysisCitation31 of the GISSI-Prevenzione study reported that treatment with omega-3 EE was effective both in patients with and without left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF >50%) with an increase of benefit in those with left ventricular dysfunction, in whom omega-EE appeared more effective in reducing sudden death.

More recently, the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter OMEGA study evaluated the effect of omega-3 EE 1 g/day on the rate of sudden cardiac death in patients with MI in the previous 3–14 days, with a 12-month follow-up. Secondary endpoints included total mortality, reinfarction, revascularization, rhythm abnormalities in Holter monitoring, and stroke.Citation129,Citation130 A total of 3851 patients were included in the study, 74.4% were male and 25.6% female; 24.1% and 75.9% had a LVEF <0.45 and ≥0.45, respectively; 27.0% were diabetics and 1.8% had renal failure. With regard to pharmacologic treatments at baseline, 69.5% of patients were receiving an ACE inhibitor, <94% an antiplatelet agent, 85.7% a β-blocker, and 81.5% were receiving statins. Data were reported for per protocol populations. Preliminary data showed no significant difference in the incidence of sudden cardiac death between omega-3 EE (1.5%) and placebo (1.5%) groups, neither with regard to the secondary endpoints, including total mortality (4.6% versus 3.7%), reinfarction (4.5% versus 4.1%), revascularization (27.7% versus 29.1%), arrhythmic events (1.1% versus 0.7%), and stroke (1.4 versus 0.7%). However the OMEGA study was designed assuming a sudden cardiac death rate of 1.9% in omega-3 EE recipients and 3.5% in placebo recipients, whilst the observed incidence was definitely lower (1.5% in both groups), thus making the trial heavily underpowered.Citation130

Heart failure

Several observational and clinical studies have reported an association between fish consumption and reduced risk of HF.Citation30,Citation32,Citation33,Citation131 As already reported above, a post hoc analysisCitation31 of the GISSI-Prevenzione studyCitation23 indicated that treatment with 1 g/day of omega-3 EE had similar beneficial effects on total mortality in patients with (LVEF ≤50%, RR 0.76; 0.60–0.96, P = 0.02) and without left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF >50%, RR 0.81; 0.59–1.10, P = 0.17). Moreover, the treatment appeared more effective in reducing sudden cardiac death in patients than those without left ventricular dysfunction.

Recently, the results of the GISSI-HF study, a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial investigating the efficacy of omega-3 EE in chronic HF were published.Citation26 A total of 6975 patients aged 18 years or older, with clinical evidence of HF of any cause and New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II–IV were randomized to 850–882 mg EPA-DHA daily as EE or matching placebo, and followed for a median of 3.9 years. Healthy lifestyle advice and evidence-based medical therapy for HF were positively recommended to all participants. The mean age of the patients was 67 years (SD ± 11), 2947 (42%) were older than 70 years, and 1516 (22%) were women. At baseline, 4425 (63%), 2365 (34%), and 185 (3%) were in NYHA Class II, III, and IV, respectively; 653 (9%) had a LVEF >40%; 987 (14%) were smokers, 3809 (55%) had hypertension, 1974 (28%) diabetes mellitus, 610 (9%) peripheral vascular disease, and 256 (4%) neoplasia. With regard to medical history, 2909 (42%) had had an MI, 2137 (31%) a coronary revascularization, and 497 (4%) an ICD. Cause of HF was ischemic in 3467 (50%) patients, dilatative in 2025 (29%), hypertensive in 1036 (15%), and other or unknown in 447 (6%). At study admission, recommended medical therapy for HF was widely used: 6520 (93%) patients were being treated with blockers of the renin-angiotensin system, 4522 (65%) with β-blockers, 2740 (39%) with spironolactone, 6260 (90%) with diuretics, and 4074 (58%) with antiplatelet agents.

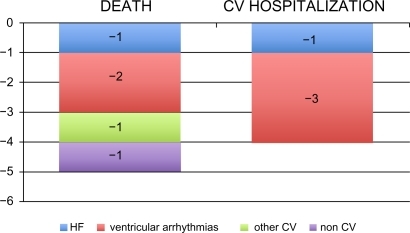

Statistically significant risk reductions in the two coprimary endpoints were observed in patients treated with omega-3 EE, ie, 9% and 8% for mortality and mortality + admission to hospital for a CV reason, respectively (). Main study results were consistent with those of the secondary analyses which were predefined in the study protocol, namely baseline characteristics, secondary outcomes, and per protocol analysis in the 4994 who were compliant with experimental treatments (). Worsening of HF and presumed arrhythmic death accounted for 62% of all deaths and were lower in the omega-3 EE group than in the placebo group. Almost half of the absolute reduction of risk that was attributable to treatment was due to the reduction of ventricular arrhythmias (mortality, 0.9% of 1.8%; first CV hospitalization, 1.0% of 1.7%). Because of the high mortality and hospitalization rates in HF patients, the apparently modest relative risk reduction due to omega-3 EE can be translated into an absolute benefit of 18 avoided deaths and 17 prevented CV hospitalizations for every 1000 patients treated for 3.9 years with omega-3 EE. In addition, the benefit in both coprimary endpoints (mortality and hospitalization) suggests that omega-3 EE might also positively affect the pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to the progression of HF.

Table 2 GISSI-HF primary outcomes, secondary outcomes, and causes of death

Safety and tolerability

In general, omega-3 EE is safe and well tolerated. In hypertriglyceridemic patients receiving omega-3 EE, either alone or in combination with simvastatin, levels of hematocrit, hemoglobin, fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, creatinine, alanine transferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), creatine phosphokinase, fibrinogen, fructosamine, homocysteine, and uric acid were not altered to a clinically significant extent.Citation45,Citation46,Citation132

However, in recipients of omega-3 EE + simvastatin 40 mg/day, a mild clinically insignificant elevation in ALT, AST, and fasting glucose levels occurred more frequently than in placebo + simvastatin 40 mg/day recipients.Citation132

With regard to safety and tolerability in post-MI patients, data from GISSI-PrevenzioneCitation23,Citation133 are reported here (the results from OMEGA trial are not yet fully available). In 4.9% and 1.4% of patients receiving omega-3 EE (1000 mg/day)-based therapy and in 2.9% and 0.4% of patients receiving tocopherol (300 mg/day)-based therapy, treatment-emergent gastrointestinal disturbances and nausea were observed. Cancer developed in 2.7% of patients receiving omega-3 EE alone, 2.3% of those receiving omega-3 EE + tocopherol, 2.6% of those receiving both, and 2.2% of control group; 1.5%, 0.9%, 1.2%, and 1.2% of patients, respectively, developed nonfatal cancer. Therapy was discontinued by 11.6% of patients receiving omega-3 EE versus 7.3% of patients receiving tocopherol at 12 months while, at 42 months 28.5% versus 26.2% of patients discontinued therapy, respectively. Adverse events leading to permanent discontinuation of therapy occurred in 3.8% of patients receiving omega-3 EE and 2.1% of patients receiving tocopherol.

Amongst the 6975 HF patients in the GISSI-HF trial, 28.7% of those allocated to omega-3 EE and 29.6% of those receiving placebo were no longer taking the study drug for various reasons. An adverse drug reaction was the cause of permanent discontinuation in 2.9% of omega-3 EE recipients and 3.0% of placebo recipients, with gastrointestinal disorders being the most frequent cause in both groups (2.7% and 2.6%, respectively).Citation26

Available evidence indicates that oral administration of 1000 mg omega-3 EE is generally well tolerated. Indeed, treatment-emergent adverse events associated with omega-3 EE both in patients with hypertriglyceridemia and in more fragile populations, including patients with a previous MI or with HF, were generally gastrointestinal in nature and minor in intensity.

Conclusion

CVD results from the interaction of multiple risk factors. Therefore, the major cardiology societies provide a number of recommendations aimed at controlling these risk factors in their programs for CVD prevention.Citation36,Citation134 The first step in all programs for CVD prevention is lifestyle modification aimed at avoiding physical inactivity, an unhealthy diet, smoking, and overweight/obesity. The presence of a high level of risk or the failure of lifestyle modification warrants utilization of drug therapy.

The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III has identified elevated LDL-C levels as a major risk factor for CHD, and these are the primary target for lipid-lowering therapy. Elevated TG levels have also been identified recently as an independent risk factor for CHD.Citation135 Oral omega-3 EE, alone or in combination with simvastatin or atorvastatin, was generally effective as an adjunct to diet in the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia in adult patients. Available evidence indicates that omega-3 EE given at 3–4 grams per day significantly reduced TG levels, and significantly increased HDL-C levels compared with placebo.

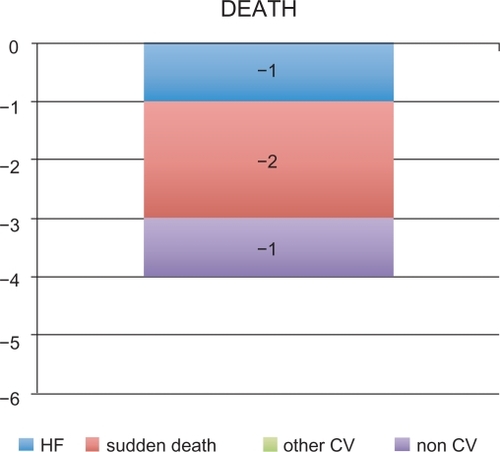

The results of GISSI-Prevenzione demonstrated that oral administration of omega-3 EE 1000 mg/day was generally effective as an adjuvant therapy to standard treatment (eg, ACE inhibitors, antiplatelet agents, β-blockers, statins) for secondary prevention in post-MI adult patients. Indeed, omega-3 EE-based therapy significantly reduced the risk of the primary composite endpoint of death + nonfatal MI + nonfatal stroke (−16%) as well as various secondary endpoints (including death, CV death, and sudden death). The reduction in the risk of the coprimary composite efficacy endpoints, can be translated into an absolute benefit of four lives saved every 1000 post-MI patients treated with omega-3 EE for one year (). The observed reduction of fatal events, especially of sudden death (−2 events) contributed to the significant reductions in the risk of the coprimary composite efficacy endpoints.

Figure 2 GISSI-Prevenzione study: Number of lives saved in every 1000 post-MI patients treated with omega-3 EE 1000 mg/day for one year.

The results of GISSI-HF showed that the administration of omega-3 EE (850–882 mg daily) in patients with chronic HF who were already receiving recommended medical therapy was effective in reducing the coprimary efficacy endpoints of all-cause mortality (−19%) and all-cause mortality or hospitalizations for CV reasons (−18%). These risk reduction can be translated into an absolute benefit of five lives saved every 1000 HF patients treated with omega-3 EE for one year (). The treatment also avoided four hospital admissions for CV reasons. As in GISSI-Prevenzione,Citation23 the main benefit appeared to be a reduction of arrhythmic events (−2 sudden deaths and −3 hospital admissions for ventricular arrhythmias, ).

Figure 3 GISSI-HF study: Number of events avoided every 1000 HF patients treated with omega-3 EE 1000 mg/day for one year.

The precise mechanisms of action of omega-3 EE are not yet fully understood. Findings from the GISSI studies suggest that the major component of the observed benefit is an antiarrhythmic effect. This hypothesis appears to be supported by previous evidence from various sources, including epidemiologic studies examining fish consumption and preclinical studies. Other factors that have been hypothesized to contribute to the cardioprotective effects of omega-3 fatty acids include effects on hemodynamics, lipid levels, endothelial function, thrombosis and hemostasis, atherogenesis, and inflammation.

According to the available evidence, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology, the European Society for Cardiology, and a number of national cardiac societies recommend the intake of 1 g/day of the two marine omega-3 fatty acids, EPA and DHA, for secondary prevention, CV prevention, treatment post-MI, and prevention of sudden cardiac death.Citation35,Citation134,Citation136–Citation138

To date, in the various European countries, oral omega-3 EE (1000 mg/day) is indicated as a component of standard treatment for secondary prevention in post-MI patients, which includes ACE inhibitors, antiplatelet agents, β-blockers, and statins.Citation20,Citation42 It is also indicated for use alone (2000–4000 mg/day) or in combination with statins, as an adjunct to diet in the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia in adult patients who have not responded to dietary measures.Citation20,Citation42 In the US, omega-3 EE is indicated as an adjunct to diet in the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia in adult patients.Citation20,Citation42

The recent results of GISSI-HF demonstrating a clinical benefit in patients with HF will probably be followed by the incorporation of omega-3 EE in the next guidelines for these patients. Indeed, despite available treatments which significantly decreased the per-year mortality in the “artificial scenario” of clinical trials, the risk of death in patients with HF remains too high in clinical practice.

Undoubtedly further studies are needed to determine the optimal dose as well as the effects of the various doses in different populations, and to clarify whether the more important mechanism for clinical benefit is the antiarrhythmic effect of omega-3 EE.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BangHODyerbergJPlasma lipids and lipoproteins in Greenlandic west coast EskimosActa Med Scand19721921–285945052396

- BangHODyerbergJNielsenABPlasma lipid and lipoprotein pattern in Greenlandic West-coast EskimosLancet197117710114311454102857

- BersotTHaffnerSHarrisWSKellickKAMorrisCMHypertriglyceridemia: Management of atherogenic dyslipidemiaJ Fam Pract2006557S1S816822443

- Kris-EthertonPMHarrisWSAppelLJFish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular diseaseCirculation2002106212747275712438303

- Kris-EthertonPMHarrisWSAppelLJOmega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: New recommendations from the American Heart AssociationArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol200323215115212588750

- PsotaTLGebauerSKKris-EthertonPDietary omega-3 fatty acid intake and cardiovascular riskAm J Cardiol2006984A3i18i

- ThompsonGRManagement of dyslipidaemiaHeart200490894995515253984

- von SchackyCThe role of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular diseaseCurr Atheroscler Rep20035213914512573200

- von SchackyCProphylaxis of atherosclerosis with marine omega-3 fatty acids. A comprehensive strategyAnn Intern Med198710768908992825573

- CastelliWPCholesterol and lipids in the risk of coronary artery disease – the Framingham Heart StudyCan J Cardiol19884Suppl A5A10A3282627

- AssmannGSchulteHRelation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides to incidence of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (the PROCAM experience). Prospective Cardiovascular Munster studyAm J Cardiol19927077337371519522

- MillerMCannonCPMurphySAQinJRayKKBraunwaldEImpact of triglyceride levels beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol after acute coronary syndrome in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trialJ Am Coll Cardiol200851772473018279736

- MillerMSeidlerAMoalemiAPearsonTANormal triglyceride levels and coronary artery disease events: The Baltimore Coronary Observational Long-Term StudyJ Am Coll Cardiol1998316125212579581716

- AustinMAKingMCVranizanKMKraussRMAtherogenic lipoprotein phenotype. A proposed genetic marker for coronary heart disease riskCirculation19908224955062372896

- ManninenVTenkanenLKoskinenPJoint effects of serum triglyceride and LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol concentrations on coronary heart disease risk in the Helsinki Heart Study. Implications for treatmentCirculation199285137451728471

- GoldbourtUBrunnerDBeharSReicher-ReissHBaseline characteristics of patients participating in the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention (BIP) StudyEur Heart J199819Suppl HH42H479717065

- MillerMDifferentiating the effects of raising low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol versus lowering normal triglycerides: Further insights from the Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention TrialAm J Cardiol20008612A23L27L

- RubinsHBRobinsSJCollinsDGemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study GroupN Engl J Med1999341641041810438259

- von SchackyCA review of omega-3 ethyl esters for cardiovascular prevention and treatment of increased blood triglyceride levelsVasc Health Risk Manag20062325126217326331

- Solvay Healthcare Limited Omacor:Summary of product characteristics Available at: http://emc.medicines.org.uk/medicine/10312/SPC/Omacor/. Accessed August 11, 2009.

- BaysHESafety considerations with omega-3 fatty acid therapyAm J Cardiol2007996A35C43C

- MozaffarianDRimmEBFish intake, contaminants, and human health: Evaluating the risks and the benefitsJAMA2006296151885188917047219

- Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: Results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto miocardicoLancet1999354917744745510465168

- HoySMKeatingGMOmega-3 ethylester concentrate: A review of its use in secondary prevention post-myocardial infarction and the treatment of hypertriglyceridaemiaDrugs20096981077110519496632

- LeeJHO’KeefeJHLavieCJMarchioliRHarrisWSOmega-3 fatty acids for cardioprotectionMayo Clin Proc200883332433218316000

- TavazziLMaggioniAPMarchioliREffect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet200837296451223123018757090

- von SchackyCHarrisWSCardiovascular benefits of omega-3 fatty acidsCardiovasc Res200773231031516979604

- HarrisWSPostonWCHaddockCKTissue n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and risk for coronary heart disease eventsAtherosclerosis2007193111017507020

- MarchioliRBarziFBombaEEarly protection against sudden death by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: Time-course analysis of the results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)-PrevenzioneCirculation2002105161897190311997274

- LevitanEBWolkAMittlemanMAFish consumption, marine omega-3 fatty acids, and incidence of heart failure: A population-based prospective study of middle-aged and elderly menEur Heart J200930121495150019383731

- MacchiaALevantesiGFranzosiMGLeft ventricular systolic dysfunction, total mortality, and sudden death in patients with myocardial infarction treated with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acidsEur J Heart Fail20057590490916087142

- MozaffarianDBrysonCLLemaitreRNBurkeGLSiscovickDSFish intake and risk of incident heart failureJ Am Coll Cardiol200545122015202115963403

- YamagishiKNettletonJAFolsomARPlasma fatty acid composition and incident heart failure in middle-aged adults: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) StudyAm Heart J2008156596597419061714

- HooperLThompsonRLHarrisonRAOmega 3 fatty acids for prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20044CD00317715495044

- HooperLThompsonRLHarrisonRARisks and benefits of omega 3 fats for mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic reviewBMJ2006332754475276016565093

- GrahamIAtarDBorch-JohnsenKEuropean guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Executive summary. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts)Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil200714Suppl 2E1E4017726406

- von SchackyCHarrisWSMozaffarianDKris-EthertonPMResponse to Hoopers et al. Cochrane Review Available at: http://www.issfal.org.uk/response-to-hoopers-et-al-cochrane-review.html. Accessed 2009 September 16.

- LeonHShibataMCSivakumaranSDorganMChatterleyTTsuyukiRTEffect of fish oil on arrhythmias and mortality: Systematic reviewBMJ2008337a293119106137

- WangCHarrisWSChungMn-3 Fatty acids from fish or fish-oil supplements, but not alpha-linolenic acid, benefit cardiovascular disease outcomes in primary and secondary prevention studies: A systematic reviewAm J Clin Nutr200684151716825676

- BryhnMHansteenHSchancheTAakreSEThe bioavailability and pharmacodynamics of different concentrations of omega-3 acid ethyl estersProstaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids2006751192416806871

- NordoyABarstadLConnorWEHatcherLAbsorption of the n-3 eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids as ethyl esters and triglycerides by humansAm J Clin Nutr1991535118518901826985

- Reliant PharmaceuticalsLovaza prescribing information Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/021654s023lbl.pdf Accessed 2009 August 11.

- Di StasiDBernasconiRMarchioliREarly modifications of fatty acid composition in plasma phospholipids, platelets and mononucleates of healthy volunteers after low doses of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acidsEur J Clin Pharmacol200460318319015069592

- GrundtHNilsenDWHetlandOImprovement of serum lipids and blood pressure during intervention with n-3 fatty acids was not associated with changes in insulin levels in subjects with combined hyperlipidaemiaJ Intern Med199523732492597891046

- HarrisWSGinsbergHNArunakulNSafety and efficacy of Omacor in severe hypertriglyceridemiaJ Cardiovasc Risk199745–63853919865671

- DurringtonPNBhatnagarDMacknessMIAn omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid concentrate administered for one year decreased triglycerides in simvastatin treated patients with coronary heart disease and persisting hypertriglyceridaemiaHeart200185554454811303007

- ToftIBonaaKHIngebretsenOCNordoyAJenssenTEffects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on glucose homeostasis and blood pressure in essential hypertension. A randomized, controlled trialAnn Intern Med1995123129119187486485

- HolmTAndreassenAKAukrustPOmega-3 fatty acids improve blood pressure control and preserve renal function in hypertensive heart transplant recipientsEur Heart J200122542843611207085

- CalderPCOmega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation and immunityWorld Rev Nutr Diet20018810911611935943

- Di SpiritoMMorelliGDoyleRTJohnsonJMcKenneyJEffect of omega-3-acid ethyl esters on steady-state plasma pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin in healthy adultsExpert Opin Pharmacother20089172939294519006470

- GosaiPLiuJDoyleRTEffect of omega-3-acid ethyl esters on the steady-state plasma pharmacokinetics of rosuvastatin in healthy adultsExpert Opin Pharmacother20089172947295319006471

- McKenneyJMSwearingenDDi SpiritoMStudy of the pharmacokinetic interaction between simvastatin and prescription omega-3-acid ethyl estersJ Clin Pharmacol200646778579116809804

- MoriTAWoodmanRJThe independent effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on cardiovascular risk factors in humansCurr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care2006929510416477172

- MakiKCMcKenneyJMReevesMSLubinBCDicklinMREffects of adding prescription omega-3 acid ethyl esters to simvastatin (20 mg/day) on lipids and lipoprotein particles in men and women with mixed dyslipidemiaAm J Cardiol2008102442943318678300

- CalabresiLDonatiDPazzucconiFSirtoriCRFranceschiniGOmacor in familial combined hyperlipidemia: Effects on lipids and low density lipoprotein subclassesAtherosclerosis2000148238739610657575

- AbeYEl-MasriBKimballKTSoluble cell adhesion molecules in hypertriglyceridemia and potential significance on monocyte adhesionArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol19981857237319598830

- MacknessMIBhatnagarDDurringtonPNEffects of a new fish oil concentrate on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in patients with hypertriglyceridaemiaEur J Clin Nutr199448128598657889894

- PownallHJBrauchiDKilincCCorrelation of serum triglyceride and its reduction by omega-3 fatty acids with lipid transfer activity and the neutral lipid compositions of high-density and low-density lipoproteinsAtherosclerosis1999143228529710217357

- StalenhoefAFde GraafJWittekoekMEBredieSJDemackerPNKasteleinJJThe effect of concentrated n-3 fatty acids versus gemfibrozil on plasma lipoproteins, low density lipoprotein heterogeneity and oxidizability in patients with hypertriglyceridemiaAtherosclerosis2000153112913811058707

- BalkEChungMLichtensteinAEffects of omega-3 fatty acids on cardiovascular risk factors and intermediate markers of cardiovascular diseaseEvid Rep Technol Assess (Summ)20049316

- RustanACNossenJOChristiansenENDrevonCAEicosapentaenoic acid reduces hepatic synthesis and secretion of triacylglycerol by decreasing the activity of acyl-coenzyme A:1,2-diacylglycerol acyltransferaseJ Lipid Res19882911141714262853717

- JumpDBFatty acid regulation of gene transcriptionCrit Rev Clin Lab Sci2004411417815077723

- LeeSSChanWYLoCKWanDCTsangDSCheungWTRequirement of PPAR-alpha in maintaining phospholipid and triacylglycerol homeostasis during energy deprivationJ Lipid Res200445112025203715342691

- SampathHNtambiJMPolyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of gene expressionNutr Rev200462933333915497766

- BaysHETigheAPSadovskyRDavidsonMHPrescription omega-3 fatty acids and their lipid effects: Physiologic mechanisms of action and clinical implicationsExpert Rev Cardiovasc Ther20086339140918327998

- McKenneyJMSicaDRole of prescription omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of hypertriglyceridemiaPharmacotherapy200727571572817461707

- ChanDCWattsGFBarrettPHBeilinLJRedgraveTGMoriTARegulatory effects of HMG CoA reductase inhibitor and fish oils on apolipoprotein B-100 kinetics in insulin-resistant obese male subjects with dyslipidemiaDiabetes20025182377238612145148

- RobinsonJGStoneNJAntiatherosclerotic and antithrombotic effects of omega-3 fatty acidsAm J Cardiol2006984A39i49i

- MakiKDavidsonMBaysHSteinEShalwitzRDoyleREffects of omega-3-acid ethyl esters on LDL particle size in subjects with hypertriglyceridemia despite statin therapyFASEB J200721231217135362

- MozaffarianDGeelenABrouwerIAGeleijnseJMZockPLKatanMBEffect of fish oil on heart rate in humans: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsCirculation2005112131945195216172267

- LeafAKangJXXiaoYFFish oil fatty acids as cardiovascular drugsCurr Vasc Pharmacol20086111218220934

- VerkerkAOvan GinnekenACBereckiGIncorporated sarcolemmal fish oil fatty acids shorten pig ventricular action potentialsCardiovasc Res200670350952016564514

- SarrazinJFComeauGDaleauPReduced incidence of vagally induced atrial fibrillation and expression levels of connexins by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in dogsJ Am Coll Cardiol200750151505151217919572

- LiYKangJXLeafADifferential effects of various eicosanoids on the production or prevention of arrhythmias in cultured neonatal rat cardiac myocytesProstaglandins19975425115309380795

- TakayamaKYuhkiKOnoKThromboxane A2 and prostaglandin F2-alpha mediate inflammatory tachycardiaNat Med200511556256615834430

- AnandRGAlkadriMLavieCJMilaniRVThe role of fish oil in arrhythmia preventionJ Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev2008282929818360184

- ChristensenJHKorupEAaroeJFish consumption, n-3 fatty acids in cell membranes, and heart rate variability in survivors of myocardial infarction with left ventricular dysfunctionAm J Cardiol19977912167016739202361

- CawoodALDingRNapperFLLong chain omega-3 fatty acids enter advanced atherosclerotic plaques and are associated with decreased inflammation and decreased inflammatory gene expressionRome, Italy2006 International Symposium on Atherosclerosis2006 June 18–22

- O’KeefeJHJrAbuissaHSastreASteinhausDMHarrisWSEffects of omega-3 fatty acids on resting heart rate, heart rate recovery after exercise, and heart rate variability in men with healed myocardial infarctions and depressed ejection fractionsAm J Cardiol20069781127113016616012

- HamaadAKaeng LeeWLipGYMacFadyenRJOral omega n3-PUFA therapy (Omacor) has no impact on indices of heart rate variability in stable post myocardial infarction patientsCardiovasc Drugs Ther200620535936417089085

- RussoCOlivieriOGirelliDOmega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplements and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring parameters in patients with mild essential hypertensionJ Hypertens19951312 Pt 2182318268903660

- BrouwerIAZockPLCammAJEffect of fish oil on ventricular tachyarrhythmia and death in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: The Study on Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Ventricular Arrhythmia (SOFA) randomized trialJAMA2006295222613261916772624

- LeafAAlbertCMJosephsonMPrevention of fatal arrhythmias in high-risk subjects by fish oil n-3 fatty acid intakeCirculation2005112182762276816267249

- RaittMHConnorWEMorrisCFish oil supplementation and risk of ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation in patients with implantable defibrillators: A randomized controlled trialJAMA2005293232884289115956633

- VargiuRLittarruGPFaaGMancinelliRPositive inotropic effect of coenzyme Q10, omega-3 fatty acids and propionyl-L-carnitine on papillary muscle force-frequency responses of BIO TO-2 cardiomyopathic Syrian hamstersBiofactors2008321–413514419096109

- DudaMKO’SheaKMTintinuAFish oil, but not flaxseed oil, decreases inflammation and prevents pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunctionCardiovasc Res200981231932719015135

- MozaffarianDGottdienerJSSiscovickDSIntake of tuna or other broiled or baked fish versus fried fish and cardiac structure, function, and hemodynamicsAm J Cardiol200697221622216442366

- McLennanPLBarndenLRBridleTMAbeywardenaMYCharnockJSDietary fat modulation of left ventricular ejection fraction in the marmoset due to enhanced fillingCardiovasc Res19922698718771451164

- PeoplesGEMcLennanPLHowePRGroellerHFish oil reduces heart rate and oxygen consumption during exerciseJ Cardiovasc Pharmacol200852654054719034030

- PepeSMcLennanPLCardiac membrane fatty acid composition modulates myocardial oxygen consumption and postischemic recovery of contractile functionCirculation2002105192303230812010914

- PepeSMcLennanPL(n-3) Long chain PUFA dose-dependently increase oxygen utilization efficiency and inhibit arrhythmias after saturated fat feeding in ratsJ Nutr2007137112377238317951473

- GeleijnseJMGiltayEJGrobbeeDEDondersARKokFJBlood pressure response to fish oil supplementation: Meta-regression analysis of randomized trialsJ Hypertens20022081493149912172309

- BonaaKHBjerveKSStraumeBGramITThelleDEffect of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids on blood pressure in hypertension. A population-based intervention trial from the Tromso studyN Engl J Med1990322127958012137901

- NordoyAHansenJBBroxJSvenssonBEffects of atorvastatin and omega-3 fatty acids on LDL subfractions and postprandial hyperlipemia in patients with combined hyperlipemiaNutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis200111171611383326

- AndreassenAKHartmannAOffstadJGeiranOKverneboKSimonsenSHypertension prophylaxis with omega-3 fatty acids in heart transplant recipientsJ Am Coll Cardiol1997296132413319137231

- MatsumotoTNakayamaNIshidaKKobayashiTKamataKEicosapentaenoic acid improves imbalance between vasodilator and vasoconstrictor actions of endothelium-derived factors in mesenteric arteries from rats at chronic stage of type 2 diabetesJ Pharmacol Exp Ther2009329132433419164460

- OmuraMKobayashiSMizukamiYEicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) induces Ca(2+)-independent activation and translocation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxationFEBS Lett2001487336136611163359

- MoriTAWattsGFBurkeVHilmeEPuddeyIBBeilinLJDifferential effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on vascular reactivity of the forearm microcirculation in hyperlipidemic, overweight menCirculation2000102111264126910982541

- McVeighGEBrennanGMCohnJNFinkelsteinSMHayesRJJohnstonGDFish oil improves arterial compliance in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitusArterioscler Thromb1994149142514298068603

- HansenJBLyngmoVSvenssonBNordoyAInhibition of exercise-induced shortening of bleeding time by fish oil in familial hypercholesterolemia (type IIa)Arterioscler Thromb1993131981048422345

- GoodfellowJBellamyMFRamseyMWJonesCJLewisMJDietary supplementation with marine omega-3 fatty acids improve systemic large artery endothelial function in subjects with hypercholesterolemiaJ Am Coll Cardiol200035226527010676668

- EnglerMMEnglerMBMalloyMDocosahexaenoic acid restores endothelial function in children with hyperlipidemia: Results from the EARLY studyInt J Clin Pharmacol Ther2004421267267915624283

- AgrenJJVaisanenSHanninenOMullerADHornstraGHemostatic factors and platelet aggregation after a fish-enriched diet or fish oil or docosahexaenoic acid supplementationProstaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids1997574–54194219430389

- KimDNEastmanABakerJEFish oil, atherogenesis, and thrombogenesisAnn N Y Acad Sci1995748474480 discussion 480–481.7535028

- MoriTABeilinLJBurkeVMorrisJRitchieJInteractions between dietary fat, fish, and fish oils and their effects on platelet function in men at risk of cardiovascular diseaseArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol19971722792869081682

- WesterveldHTde GraafJCvan BreugelHHEffects of low-dose EPA-E on glycemic control, lipid profile, lipoprotein(a), platelet aggregation, viscosity, and platelet and vessel wall interaction in NIDDMDiabetes Care19931656836888495604

- WoodmanRJMoriTABurkeVEffects of purified eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on platelet, fibrinolytic and vascular function in hypertensive type 2 diabetic patientsAtherosclerosis20031661859312482554

- TsurutaKOgawaHYasueHEffect of purified eicosapentaenoate ethyl ester on fibrinolytic capacity in patients with stable coronary artery disease and lower extremity ischaemiaCoron Artery Dis19967118378428993942

- NordoyABonaaKHSandsetPMHansenJBNilsenHEffect of omega-3 fatty acids and simvastatin on hemostatic risk factors and postprandial hyperlipemia in patients with combined hyperlipemiaArterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol200020125926510634827

- LeeKWBlannADLipGYEffects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on plasma indices of thrombogenesis and inflammation in patients post-myocardial infarctionThromb Res2006118330531216154181

- KnappHRDietary fatty acids in human thrombosis and hemostasisAm J Clin Nutr1997655 Suppl1687S1698S9129511

- HansenJBOlsenJOWilsgardLLyngmoVSvenssonBComparative effects of prolonged intake of highly purified fish oils as ethyl ester or triglyceride on lipids, haemostasis and platelet function in normolipaemic menEur J Clin Nutr19934774975078404785

- NilsenDWDalakerKNordoyAInfluence of a concentrated ethylester compound of n-3 fatty acids on lipids, platelets and coagulation in patients undergoing coronary bypass surgeryThromb Haemost19916621952011771612

- SmithPArnesenHOpstadTDahlKHEritslandJInfluence of highly concentrated n-3 fatty acids on serum lipids and hemostatic variables in survivors of myocardial infarction receiving either oral anticoagulants or matching placeboThromb Res19895354674742660319

- EritslandJArnesenHSmithPSeljeflotIDahlKEffects of highly concentrated omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and acetylsalicylic acid, alone and combined, on bleeding time and serum lipid profileJ Oslo City Hosp1989398–9971012809856

- EritslandJArnesenHGronsethKFjeldNBAbdelnoorMEffect of dietary supplementation with n-3 fatty acids on coronary artery bypass graft patencyAm J Cardiol199677131368540453

- HarrisWSExpert opinion: Omega-3 fatty acids and bleeding – cause for concern?Am J Cardiol2007996A44C46C