Abstract

CLIPPER is a chronic inflammatory disorder in the CNS, which is characterized by MRI appearance of punctate and curvilinear gadolinium enhancement that involve the pons and the cerebellum and exquisite response to steroid. We report a patient presented with clinical and radiological features suggestive of CLIPPERS. However, despite the initial response to steroid, there were dramatic changes in the course of his disease that were conducive to considering another diagnosis. We searched PubMed using word (CLIPPERS) till December 2018. The pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, imaging features, treatment and prognosis of this disorder are summarized. A review of the literature for cases of CLIPPERS demonstrated a subset of patients who later discovered to have an alternative pathology. Indeed, clinicians should be scrupulous to diagnose this disease based solely on the clinical and radiological findings and they should have a lower threshold of having a brain biopsy.

Case report

Twenty-one-year-old Saudi male presented to our emergency room in March 2016 with a 2-week history of progressive paresthesia of the right arm, which then spread over days to involve the right part of the face and the right leg with a tendency to fall toward the right side. The patient had no transient neurological symptoms in the past and there was no family history of any neurological disorders. Review of systems, including the rheumatological review was negative. His past history was significant for nonfocal brucellosis, which was successfully treated 2 years before with a 6-week course of antibiotics.

His neurological examination revealed diminished sensation to pin prick and right touch in the right V1–3 trigeminal divisions with intact cornea reflex. The motor examination was significant for increased tone and brisk deep tendon reflexes in both upper and lower limbs. Besides, he had obvious right-sided cerebellar signs in the form of horizontal nystagmus, intention tremor and dysmetria on finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin testing. His general and systemic examinations were otherwise normal.

Laboratory workup was all negative and it included: complete blood count (CBC), chemistry, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), CRP, complement C3 and 4, angiotensin-converting enzymes, brucella, toxoplasma, HIV, hepatitis B and C, infectious mononucleosis, tuberculosis PCR, mycoplasma, salmonella, syphilis, varicella zoster, human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV), fungal culture, tumor markers and autoimmune profile (rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anti Ds-DNA, antismith antibody, anti-Ro, anti-la, antiphospholipid antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody [ANCA], anti-RNP, neuromyelitis optica aquaporin-4 antibody).

Chest x-ray and upper abdomen ultrasound were normal. Computed tomography (CT) of thorax, abdomen and pelvis did not show any lymphadenopathy or other abnormalities suggestive of lymphoma, primary neoplasm or sarcoidosis.

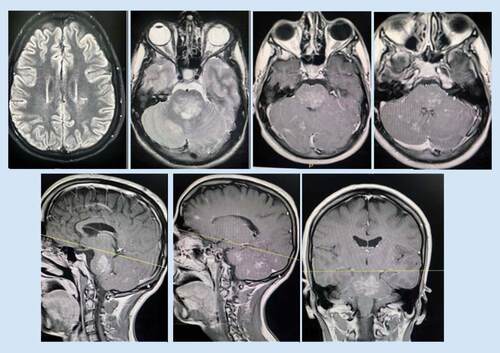

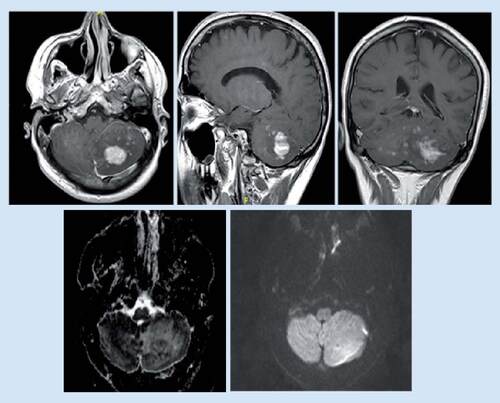

MRI brain demonstrated multiple ill-defined areas of signal abnormality involving the brainstem, cerebellum and left posterior parietal periventricular white matter. They elicit iso to low signal in T1 and high T2/FLAIR signal with patchy postcontrast enhancement. The largest lesion is seen involving the posterior aspect of the brainstem, mainly the pons and associated with mild mass effect. No significant mass effect related to other lesions (). Spinal MRI and conventional cerebral angiography were normal.

They elicit iso to low signal in T1 and high T2/FLAIR signal with patchy postcontrast enhancement. The largest lesion is seen involving the posterior aspect of the brainstem, mainly the pons.

CSF examination showed mild pleocytosis (total leucocytes: 13.00/μl) mainly lymphocytic, mildly increased protein (CSF Protein 60.80 H mg/dl), while CSF culture, tuberculosis (TB) PCR and herpes simplex virus (HSV) PCR were all negative.

In view of the patient’s clinical picture and the absence of another convincing explanation along with the typical salt-and-pepper like appearance of the MRI brain, the patient was treated as a probable case of CLIPPERS. Accordingly, he was commenced on a 5-day course of methylprednisolone 1000 mg once daily, followed by oral prednisolone 60 mg once daily.

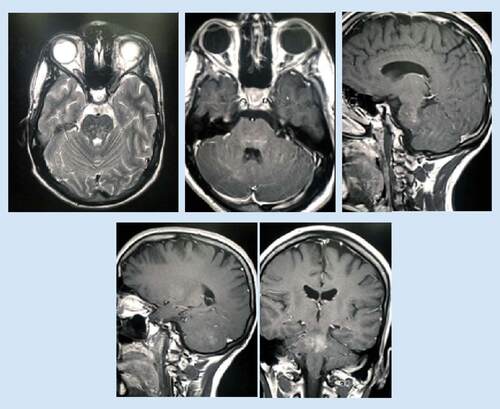

After 2 months of treatment, the patient reported marked improvement of his symptoms and marked regression of the brain lesions was observed in the MRI ().

Consequently, azathioprine 50 mg once daily was added with gradual reduction of prednisolone. However, in October 2016, the patient developed azathioprine-induced neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (white blood cell [WBC] 2.4, neutrophils 0.06, platelet [Plt] 18). Therefore, azathioprine was replaced by methotrexate 7.5 mg once daily. At that time, his MRI brain revealed no significant changes of the previously detected areas of abnormal signal intensity as regards the size and distribution and his repeated chest and abdominal CT was normal.

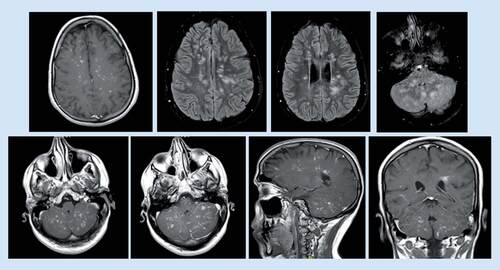

Unfortunately, the patient represented in January 2017 with new onset dysarthria when the dose of prednisolone was reduced to 20 and 15 mg on alternate days. At that time, MRI brain revealed progressive changes of the previously noted abnormal signal intensity at brain stem, cerebellum and bilateral parietal white matter, with significant enhancement at postcontrast study ().

Subsequently, methylprednisolone 1000 mg once daily for 5 days was commenced. The patient then was started on rituximab injection weekly for four doses and was maintained on prednisolone 30 mg tab orally (po.) once daily and mycophenolate 500 mg tab po. twice daily.

After this treatment, the patient’s symptoms improved and his repeated MRI in May 2017 demonstrated significant regression regarding the previously seen abnormal cerebral white matter signal intensity and brain stem with markedly regression of the pattern of enhancement in postcontrast study. However, there was mild increase in the size of the previously seen cerebellum abnormal signal intensity ().

However, there was a mild increase in the size of the previously seen cerebellum abnormal signal intensity.

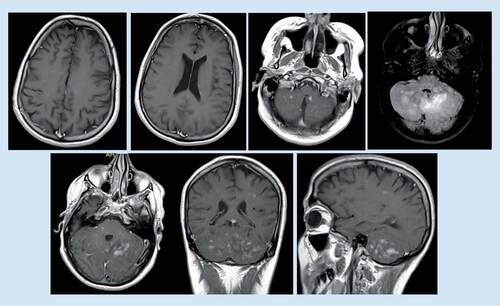

While there had been no new neurological symptoms, a follow-up MRI brain was done in August 2017 (), which revealed a new left cerebellar mass-like lesion.

Mild increased in size, pattern of enhancement and related mass effect regarding the previously seen left cerebellum abnormal signal with one mass-like lesion measuring about 27 × 20 mm that presenting homogeneous enhancement raising the possibility of lymphoma.

Thereafter, in November 2017, the patient was referred to Germany for further workup. Stereotactic brain biopsy from the cerebellar area had been taken and reviewed by several neuropathologists who agreed on the diagnosis of Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD). On the other hand, a biopsy from bone marrow was not conclusive. Furthermore, a RUNX1 mutation was found only in the blood, which probably suggests the susceptibility to hematological malignancy. Consequently, the patient was commenced on high-dosage IFN-α with initial stabilizing effect. However, he developed pancytopenia that was not known clearly whether it was due to the disease itself or due to immunosuppression therapy. Additionally, the patient developed thrombosis of the left femoralis profundus vein that warranted the use of full anticoagulation therapy. Unfortunately, the patient was admitted again in February 2018 with deterioration of the level of consciousness, which was proved to be due to bilateral multiple intracerebral hemorrhages. In the aftermath, the patient underwent rehabilitation but, regrettably, his condition had further deteriorated and he eventually died due to severe pneumonia and sepsis.

Discussion

CLIPPERS is a brainstem predominant encephalomyelitis that characterized by punctate curvilinear postgadolinium contrast enhancement centered in the pons and cerebellum on brain MRI, with biopsy findings consisting of prominent perivascular CD3+ T-cell predominant lymphocytic inflammation, and an exquisite clinical and radiographic response to corticosteroids [Citation1]. The incidence and prevalence of CLIPPERS is unknown. The male:female ratio is approximately 2.2:1 [Citation2,Citation3].

The exact cause and pathogenesis of CLIPPERS has not been revealed yet. The inflammatory nature of the disease is substantiated by the response to steroid [Citation1,Citation3], and the perivascular T-cell infiltration, with a predominance of CD4 cells [Citation1].

Symptoms typically evolve over weeks or months with a relapsing-remitting course. A rapid onset of symptoms is atypical for CLIPPERS [Citation4]. The patients usually present with subacute gait ataxia and diplopia, facial tingling [Citation1], dizziness, pseudobulbar affect [Citation5], tinnitus [Citation5], tremor [Citation6], nystagmus [Citation5,Citation6], long-tract signs [Citation6,Citation7], paraparesis [Citation5,Citation6], cognitive dysfunctions and disruption of executive function [Citation3,Citation7].

Brain MRI in CLIPPERS is characterized by small (<3 mm) punctate, curvilinear postgadolinium-enhanced lesions located in the pons and cerebellum [Citation1,Citation6,Citation8]. These lesions become less numerous further away from the pons [Citation1]. Bilateral location is an important feature of CLIPPERS; therefore, the presence of unilateral larger confluent lesions should be carefully evaluated for alternate causes such as neoplasms or granulomatous diseases [Citation2,Citation4]. Another important feature of CLIPPERS is the clinical and radiological remission with corticosteroid treatment. Therefore, a lack of robust radiological response should prompt consideration of alternative etiologies [Citation2]. Also, severe edema or mass effect on MRI [Citation5] and pial enhancement [Citation9] are red flags that warrant search for alternative diagnosis.

CSF analysis usually reveals mild pleocytosis and mild protein elevation [Citation1,Citation3]. Oligoclonal bands are occasionally seen and are often transient [Citation1,Citation3]. CSF β-2 microglobulin levels were reported as normal in one case [Citation10] and markedly elevated in another case of CLIPPERS [Citation11].

Biopsies from the affected areas show a predominant perivascular infiltration of CD3+ T cells, most of which are also CD4+ [Citation1]. CD68+ histiocytes can be present in moderate numbers, and infiltrating macrophages as well as a small number of neutrophils and eosinophils are found in some cases [Citation5,Citation7]. B cells are generally seen in smaller numbers than T cells [Citation1,Citation2]. Of note, perivascular T-cell infiltrates that are seen in CLIPPERS can also be seen in primary CNS lymphoma sentinel lesions and grade I lymphomatoid granulomatosis, indicating that the typical pathological findings in CLIPPERS are probably nonspecific [Citation12].

The diagnosis of CLIPPERS often constitutes a diagnostic dilemma as there is long list of differential diagnosis [Citation3,Citation8] (see ).

Table 1. Differential diagnosis of CLIPPERS.

In our patient’s case, the negative workup of systemic diseases, the subacute onset of the pure neurological symptoms along with the brain MRI led us to consider the diagnosis of CLIPPERS. Furthermore, the initial response to steroids bolstered this possibility. Even more interestingly, the patient’s relapse occurred when we attempted prednisolone tapering below 20 mg that was supportive of CLIPPERS. The absence of the alternative diagnosis and the potential complications of brain biopsy on the other hand led us to avoid the invasive procedure at this early stage.

On the course of treatment, the patient developed pancytopenia that happened only after the initiation of azathioprine and was corrected after the discontinuation of the medication. The normal repeated chest and abdomen CT and the absence of evidence of hematological malignancy in the blood film and later bone marrow further supported the notion that azathioprine was the culprit for this pancytopenia rather than considering another diagnosis.

The patient’s second relapse occurred when we decreased the dose of prednisolone because of the side effects and also after the initiation of methotrexate instead of azathioprine. However, the involvement of the brain parenchyma was conducive toward reconsidering the diagnosis in spite of improvement of these lesions with the high-dose steroid and rituximab. Furthermore, the emergence of the cerebellar mass was a red flag considering the fact that CNS malignancies were reported previously in patients initially diagnosed with CLIPPERS [Citation9,Citation13–17], therefore, our case is a demonstration of the well-recognized type of clipper that was suspected to be complicated with the lymphoma. However, there were also cases where CLIPPER disease developed after remission of lymphoma [Citation2,Citation9,Citation17–21] that seems to be less common (see ).

Table 2. Reported cases of CLIPPERS including the cases who were discovered to have alternative diagnosis.

To our best knowledge, this would be the second case of ECD that was presumably diagnosed as CLIPPERS. Importantly, in the case reported by Berkman et al. [Citation67], CT scan of the abdomen revealed perirenal soft tissue infiltration from which the biopsy revealed foamy non-Langerhans histiocytes compatible with a diagnosis of ECD. In contrast, our patient’s initial symptoms were purely neurological and even CT scan of chest and abdomen, which was repeated twice did not give any clue to the possibility of systemic disease.

Even after the biopsy and consideration of the diagnosis of ECD, our case was a puzzle that even posed more inexplicable questions. Intriguingly, the lesions remained restricted to the brain for about 1.5 years with no evidence of other organ affection. Also, the condition of the patient markedly deteriorated after the initiation of PEGylated IFN-α and decreasing the prednisolone to 15 mg once daily and we do not know whether this deterioration is related to the natural course of the disease or to the treatment itself. Generally, our case raises the issue of the appropriate time to take the biopsy. Reticence can be understandable considering the potential risks of the procedure and the lack of specificity of the histopathology finding in CLIPPERS; however, as in our case, it could have been the only way to save the early diagnosis of an underlying serious disease.

Conclusion & future perspective

Clinically and radiologically compatible CLIPPERS may conceal a number of serious pathologies. Therefore, we emphasize on the necessity of the brain biopsy to secure the definitive diagnosis of CLIPPERS and differentiating it from its mimics.

CLIPPERS is an increasingly recognized entity within the spectrum of inflammatory CNS disorders.

The clinical symptoms are related directly to the predilection of the disease to involve the brainstem and the cerebellum.

The MRI is characterized by punctate or curvilinear gadolinium enhancement in the pons and cerebellum.

Clinical and radiological response to steroid is a pillar for the diagnosis of CLIPPERS.

The pathological findings in CLIPPERS are perivascular lymphocytic inflammation with a CD4+ T-cell predominance.

Given the broad differential diagnosis, an extensive workup is required to exclude the mimics of the disease.

The development of a brain mass is a red flag that necessitates the search for an alternative diagnosis.

In the absence of specific biomarkers, we believe that brain biopsy remains the only method to secure a definitive diagnosis of CLIPPERS.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical consent disclosure

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images and this was attained from the Research Ethics Committee in the Security Forces Hospital Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

References

- PittockS, DebruyneJ, KreckeKet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS). Brain133(9), 2626–2634 (2010).

- TobinWO, GuoY, KreckeKNet al.Diagnostic criteria for chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS). Brain140(9), 2415–2425 (2017).

- DudesekA, RimmeleF, TesarSet al.CLIPPERS: chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids. Review of an increasingly recognized entity within the spectrum of inflammatory central nervous system disorders. Clin. Exp. Immunol.175(3), 385–396 (2014).

- TaiebG, DuflosC, RenardDet al.Long-term outcomes of CLIPPERS (chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids) in a consecutive series of 12 patients. Arch. Neurol.69(7), 847–855 (2012).

- CiprianiVP, ArndtN, PytelPet al.Effective treatment of CLIPPERS with long-term use of rituximab. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm.5(3), e448 (2018).

- BlaabjergM, RuprechtK, SinneckerTet al.Widespread inflammation in CLIPPERS syndrome indicated by autopsy and ultra-high-field 7T MRI. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm.3(3), e226 (2016).

- ZalewskiNL, TobinWO. CLIPPERS. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep.17(9), 65 (2017).

- TaiebG, Duran-PeñaA, DeChamfleur NMet al.Punctate and curvilinear gadolinium enhancing lesions in the brain: a practical approach. Neuroradiology58(3), 221–235 (2016).

- AlsherbiniK, BeinlichB, SalamatMS. Diffusely infiltrating central nervous system lymphoma involving the brainstem in an immune- competent patient. JAMA Neurol.71(1), 110–111 (2014).

- ButtmannM, MetzI, BrechtIet al.Atypical chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontocerebellar perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS), primary angiitis of the CNS mimicking CLIPPERS or overlap syndrome? A case report. J. Neurol. Sci.324(1-2), 183–186 (2013).

- FujisawaN, OyaS, MoriHet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids with a significant elevation of β-2 microglobulin levels. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc.58(5), 487 (2015).

- PesaresiI, SabatoM, DesideriIet al.3.0T MR investigation of CLIPPERS: role of susceptibility weighted and perfusion weighted imaging. Magn. Reson. Imaging31(9), 1640–1642 (2013).

- TaiebG, Uro-CosteE, ClanetMet al.A central nervous system B-cell lymphoma arising two years after initial diagnosis of CLIPPERS. J. Neurol. Sci.344(1), 224–226 (2014).

- JonesJL, DeanAF, AntounNet al.Radiologically compatible CLIPPERS'may conceal a number of pathologies. Brain134(8), e187–e187 (2011).

- LimousinN, PralineJ, MoticaOet al.Brain biopsy is required in steroid-resistant patients with chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS). J. Neurooncol.107(1), 223–224 (2012).

- DeGraaff HJ, WattjesMP, Rozemuller-KwakkelAJet al.Fatal B-cell lymphoma following chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids. JAMA Neurol.70(7), 915–918 (2013).

- WangX, HuangD, HuangXet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS): a lymphocytic reactive response of the central nervous system? A case report. J. Neuroimmunol.305, 68–71 (2017).

- ReddySM, LathR, SwainMet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS): a case report and review of literature. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol.18(3), 345 (2015).

- NakamuraR, UenoY, AndoJet al.Clinical and radiological CLIPPERS features after complete remission of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified. J. Neurol. Sci.364, 6–8 (2016).

- MashimaK, SuzukiS, MoriTet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) after treatment for Hodgkin's lymphoma. Int. J. Hematol.102(6), 709–712 (2015).

- MaY, SunX, LiWet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) with intracranial Epstein–Barr virus infection: a case report. Medicine95(46), e5377 (2016).

- KastrupO, VanDe Nes J, GasserTet al.Three cases of CLIPPERS: a serial clinical, laboratory and MRI follow-up study. J. Neurol.258(12), 2140–2146 (2011).

- GabilondoI, SaizA, GrausFet al.Response to immunotherapy in CLIPPERS syndrome. J. Neurol.258(11), 2090–2092 (2011).

- LefaucheurR, BouwynJP, AhtoyPet al.Teaching neuroimages: punctuate and curvilinear enhancement peppering the pons responsive to steroids. Neurology77(10), e57–e58 (2011).

- LefaucheurR, BourreB, Ozkul-WermesterOet al.Stroke mimicking relapse in a patient with CLIPPERS syndrome. Acta Neurologica Belgica.115(4), 735–736 (2015).

- ListJ, LesemannA, WienerEet al.A new case of chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids. Brain134(8), e185– (2011).

- TaiebG, WacongneA, RenardDet al.A new case of chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids with initial normal magnetic resonance imaging. Brain134(8), e182 (2011).

- BiottiD, DeschampsR, ShotarEet al.CLIPPERS: chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids. Pract. Neurol.11(6), 349–351 (2011).

- SimonNG, ParrattJD, BarnettMHet al.Expanding the clinical, radiological and neuropathological phenotype of chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS). J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry83(1), 15–22 (2012).

- TohgeR, NagaoM, YagishitaAet al.A case of chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) in East Asia. Intern. Med.51(9), 1115–1119 (2012).

- HillesheimPB, ParkerJR, ParkerJr JCet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids following influenza vaccination. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med.136(6), 681–685 (2012).

- SempereAP, MolaS, Martin‐MedinaPet al.Response to immunotherapy in CLIPPERS: clinical, MRI, and MRS follow‐up. J. Neuroimaging23(2), 254–255 (2013).

- WetterA, KüpeliG, MeilaDet al.CLIPPERS syndrome in a patient with a fluctuating cerebellar syndrome. Neurographics3(1), 11–13 (2013).

- FerreiraRM, MachadoG, SouzaASet al.CLIPPERS-like MRI findings in a patient with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci.327(1-2), 61–62 (2013).

- WijntjesJ, WoudaEJ, SiegertCEet al.Need for prolonged immunosupressive therapy in CLIPPERS-a case report. BMC Neurol.13(1), 49 (2013).

- HaAD, ParrattJD, BabuSet al.Movement disorders associated with CLIPPERS. Mov. Disord.29, 148–150 (2014).

- SmithA, MatthewsY, KossardSet al.Neurotropic T‐cell lymphocytosis: a cutaneous expression of CLIPPERS. J. Cutan. Pathol.41(8), 657–662 (2014).

- Kleinschmidt-DeMastersBK, WestM. CLIPPERS with chronic small vessel damage: more overlap with small vessel vasculitis?J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol.73(3), 262–267 (2014).

- UenoH, TomimuraH, YoshimotoTet al.Paroxysmal dysarthria and ataxia in chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids. Neurol. Clin. Neurosci.2(1), 13–15 (2014).

- Kerrn-JespersenBM, LindelofM, IllesZet al.CLIPPERS among patients diagnosed with non-specific CNS neuroinflammatory diseases. J. Neurol. Sci.343(1-2), 224–227 (2014).

- LaneC, PhadkeR, HowardR. An extended chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids phenotype. BMJ Case Rep.2014, pii: bcr2014204117 (2014).

- MéléN, GuiraudV, LabaugePet al.Effective antituberculous therapy in a patient with CLIPPERS: new insights into CLIPPERS pathogenesis. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm.1(1), e6 (2014).

- BagAK, DavenportJJ, HackneyJRet al.Case 212: chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids. Radiology273(3), 940–947 (2014).

- WangL, HolthausEA, JimenezXFet al.MRI evolution of CLIPPERS syndrome following herpes zoster infection. J. Neurol. Sci.348(1), 277–278 (2015).

- SuerD, YusifovaL, ArsavaEMet al.A case report of CLIPPERS (chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontocerebellar perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids) syndrome. Clin. Neuroradiol.25(1), 61–63 (2015).

- TanBL, AgzarianM, SchultzDW. CLIPPERS: induction and maintenance of remission using hydroxychloroquine. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm.2(1), e56 (2015).

- MoreiraI, CrutoC, CorreiaCet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) postmortem findings. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol.74(2), 186–190 (2015).

- MarinhoPB, MontanaroVV, FreitasMCet al.CLIPPERS syndrome: case report in a Brazilian patient with a long term disease evolution. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord.4(4), 311–314 (2015).

- SymmondsM, WatersPJ, KükerWet al.Anti-MOG antibodies with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis preceded by CLIPPERS. Neurology84(11), 1177–1179 (2015).

- EsmaeilzadehM, YildizÖ, LangJMet al.CLIPPERS syndrome: an entity to be faced in neurosurgery. World Neurosurg.84(6), 2077–e1 (2015).

- WengCF, ChanDC, ChenYFet al.Chronic hepatitis B infection presenting with chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS): a case report. J. Med. Case Rep.9(1), 266 (2015).

- GulM, ChaudhryAA, ChaudhryAAet al.Atypical presentation of CLIPPERS syndrome: a new entity in the differential diagnosis of central nervous system rheumatologic diseases. J. Clin. Rheumatol.21(3), 144–148 (2015).

- ZhangYX, HuHT, DingXYet al.CLIPPERS with diffuse white matter and longitudinally extensive spinal cord involvement. Neurology86(1), 103–105 (2016).

- RicoM, VillafaniJ, TuñónAet al.IFN beta 1a as glucocorticoids-sparing therapy in a patient with CLIPPERS. Am. J. Case Rep.17, 47–50 (2016).

- HouX, WangX, XieBet al.Horizontal eyeball akinesia as an initial manifestation of CLIPPERS: case report and review of literature. Medicine95(34), e4640 (2016).

- AbkurTM, KearneyH, HennessyMJ. CLIPPERS and the need for long-term immunosuppression. Scott. Med. J.62(1), 28–33 (2017).

- MubasherM, SukikA, BeltagiEet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids, with cranial and caudal extension. Case Rep. Neurol. Med.2593096 (2017).

- OhtaY, NomuraE, TsunodaKet al.Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS) with limbic encephalitis. Intern. Med.56(18), 2513–2518 (2017).

- CordanoC, LópezGY, BollenAWet al.Occipital headache in chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids (CLIPPERS). Headache58(3), 458–459 (2018).

- RösslingR, PehlD, LingnauMet al.A case of CLIPPERS challenging the new diagnostic criteria. Brain141(2), e12– (2017).

- BerzeroG, TaiebG, MarignierRet al.CLIPPERS mimickers: relapsing brainstem encephalitis associated with anti‐MOG antibodies. Eur. J. Neurol.25(2), e16–17 (2018).

- OlmesDG, MetzI, LeeDHet al.CLIPPERS with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis: role of T versus B cells. J. Neurol. Sci.385, 96–98 (2018).

- WallRJ. Chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids with seizures and central pyrexia, in a patient requiring tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation: a case report. J. Intensive Care Soc.19(2), 167–170 (2018).

- BobbaS, NarasimhanM, ZagamiAS. Isolated painful trigeminal neuropathy as an unusual presentation of chronic lymphocytic inflammation with pontine perivascular enhancement responsive to steroids: a case report. Cephalalgia39(2), 316–322 (2019).

- DidierPG, AdriánMG, PaolaSGet al.CLIPPERS syndrome responsive to Leflunomide: a case report. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord.25, 265–267 (2018).

- YiF, TianY, ChenXYet al.Two cases of CLIPPERS with increased number of perivascular CD20-positive B lymphocytes. Brain141(10), e75– (2018).

- BerkmanJ, FordC, JohnsonEet al.Misdiagnosis: CNS Erdheim–Chester disease mimicking CLIPPERS. Neuroradiol. J.31(4), 399–402 (2018).