Abstract

Aims: To evaluate how well the EQ-5D-5L, a generic preference-based measure of health-related quality of life, captures caregiver burden in a rare pediatric neurotransmitter disease. Materials & methods: Caregivers (n = 14) of individuals with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency completed qualitative interviews on their experience as a caregiver, the EQ-5D-5L and a background questionnaire. Qualitative and quantitative data were compared to determine whether there was concordance or discordance in the findings. Results: No caregivers reported problems with mobility and self-care in either the qualitative interviews or on the EQ-5D-5L, and there was general concordance for pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. However, discordance was found for usual activities, with 79% reporting no problems with this dimension on the EQ-5D-5L, compared with 100% describing substantial limitations during the interviews. Conclusion: The EQ-5D-5L may not be appropriate to evaluate caregiver burden in AADC deficiency, where caregivers' perceptions of “usual activities” differ substantially from the general population.

Plain language summary

This study aimed to investigate how well the EQ-5D-5L, a quality-of-life questionnaire, measures the burden of caring among caregivers of children with rare diseases. Fourteen caregivers of children with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency were interviewed about their experience as a caregiver and completed the EQ-5D-5L based on their own quality of life and a background questionnaire. Caregivers' responses in the interviews and the EQ-5D-5L were similar for most categories (mobility, self-care, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). However, all caregivers reported problems with their usual activities in the interviews, but only a few reported this in the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. This suggests there may be problems with using the EQ-5D-5L to measure the impact of caring for a child with a rare disease.

Traditionally, cost–effectiveness analyses have focused solely on assessing the impacts of treatments on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients [Citation1], but it is now recognized that in many diseases there is also a substantial impact on the health and wellbeing of caregivers and other family members [Citation2–5]. Failure to capture this impact on caregivers in economic evaluations can lead to the full burden of disease and benefits of treatments being underestimated [Citation6], potentially limiting access to treatment. This broader view is reflected in the increasing use of caregiver disutilities in NICE submissions from zero in 2005 [Citation7], rising to two in 2008 [Citation8], six in 2012 [Citation9] and 16 in January 2019 [Citation10]. The EQ-5D has been widely adopted to capture caregiver (dis)utilities for use in economic evaluations of new treatments.

NICE in the United Kingdom has specified a preference for the EQ-5D to be used to measure HRQoL (utility) in cost-effectiveness analyses [Citation11,Citation12]. The EQ-5D is a generic preference-based measure of HRQoL that is widely used in clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of new treatments [Citation13,Citation14]. It assesses five dimensions of health, including mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, as well as overall health. Responses are used to generate health utilities, which are used in the calculation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) to quantify the cost-effectiveness of new treatments. A health utility of 1 indicates full health, in which an individual has no problems with the five dimensions of the EQ-5D; in the original time trade-off interviews to develop the preference weights, this equates to no willingness to trade any years of life to avoid this state versus “full health." A health utility of 0 equals the health state of dead and values <0 represent states worse than dead (i.e., indicating a preference for being dead rather than living in that health state).

Although the EQ-5D is widely used in economic evaluations to quantify the HRQoL impact on informal caregivers, there is some evidence in the literature that when used for chronic health conditions and longer-term caregiver roles (such as caregivers to children with congenital diseases), measurement error or lack of sensitivity may occur. For example, in a clinical trial for cystic fibrosis, those with mild and severe lung function reported baseline health utility scores of 0.923 and 0.870, respectively [Citation15], which are both higher than the population norms for the UK (0.856) and the USA (0.867) [Citation16]. In the context of capturing informal caregiver HRQoL, a study involving caregivers of children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) found that certain subgroups of caregivers had better HRQoL than the general population as measured by the EQ-5D [Citation17]. The authors hypothesized that this may be due to some parents perceiving their informal caregiving tasks as normal tasks, unable to distinguish between their role as caregiver and a "normal" parenting role.

Based on these findings, the current study was designed to examine the content validity of the EQ-5D and explore whether the instrument adequately captures the informal caregiver burden in pediatric disease. To do this, a mixed-methods study was conducted with caregivers of individuals with aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency, a rare neurometabolic disorder that is associated with a wide range of symptoms and functional issues and requires round-the-clock care [Citation18–20].

Materials & methods

Study design

This study employed a mixed-methods convergent design, which involved collecting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data within a similar timeframe and giving equal priority and weighting to both research methods [Citation21]. The quantitative component included the EQ-5D-5L and a background questionnaire and the qualitative component comprised semistructured interviews. Further details on the methods for this study are described elsewhere [Citation20,Citation22].

Participants

Participants were unpaid caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency. To meet the inclusion criteria, participants had to be the main caregiver (provide at least 50% of daily care) of an individual with AADC deficiency, aged ≥18, able and willing to provide informed consent and reside in the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, the United States or Canada. Moreover, participants had to affirm that the individuals they cared for had a confirmed diagnosis of AADC deficiency based on at least two of the following three tests: molecular genetic testing of the DDC gene, blood AADC enzyme activity and CSF neurotransmitter analysis. Caregivers of individuals who had been treated with gene therapy were excluded.

Study materials

Quantitative measures included the EQ-5D-5L and a background questionnaire. The background questionnaire included tailored questions on time spent caring for the individual with AADC deficiency, the impact of being a caregiver and the support received with caring, as well as sociodemographic data and disease and treatment questions. The qualitative interviews were guided by a semistructured interview guide developed based on the published literature on the HRQoL of individuals with AADC deficiency and informal interview discussions with clinical experts and caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency in Spain (n = 2). The interview guide contained mostly open-ended questions on caregivers' views about the patient's daily experience living with the condition and their own experiences of caring for someone with the condition. This included questions designed to elicit qualitative data related to each of the EQ-5D dimensions. Detailed findings from the interviews on the impacts on the individual with AADC and the caregiver experience have been reported elsewhere [Citation20,Citation22].

Ethics review & approval

This study was submitted for ethical review to the WIRB-Copernicus Group Independent Review Board and was granted an exemption (tracking number: #1-1327023-1).

Recruitment & data collection

Participants were recruited by a specialist recruitment agency. All participants were provided with an information sheet about the study, including a statement about the possibility that their data would be included in academic journals, and gave verbal informed consent to take part in the study. The interviews in the United States were conducted by two study authors. The remaining interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in each study country in the local language. Interviews were conducted by telephone/videoconference between September and December 2020. The interviews followed the interview guide and lasted around 1 h. Interviews were recorded and transcribed, then deidentified and translated into English (prior to analysis) by a specialist translation vendor.

Analyses

The quantitative and qualitative data were first analyzed separately and these findings were then compared with corroborated or contextualized observed phenomena and any potential discrepancies between the two datasets were highlighted. Data from the background questionnaire and the EQ-5D-5L were analyzed in Microsoft Excel (Version 16.60) using descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and the count and percentage for categorical variables. Health utilities were estimated from the EQ-5D-5L using UK population weights [Citation23].

Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis in MAXQDA. Two researchers read the transcripts and developed a coding framework based on the topics covered in the interview guide. One researcher then coded a sample of transcripts and these were reviewed by a second researcher and discrepancies were discussed. The coding framework was revised following this discussion and data-driven amendments were made as needed. After coding, the data were summarized according to the dimensions of the EQ-5D. Findings from the quantitative and qualitative components of the study were then compared with corroborated or contextualized observed phenomena and whether there was agreement (convergence) or contradictions (dissonance) between the two datasets on data relating to the five dimensions of the EQ-5D was determined.

Results

Sample characteristics

Fourteen caregiver interviews were conducted with 10 mothers, two fathers, one brother and one aunt. Two caregivers were parents of the same individual. The characteristics of the caregivers (n = 14) and individuals with AADC deficiency (n = 13) are shown in .

Table 1. Characteristics of caregivers and individuals with aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency.

EQ-5D-5L

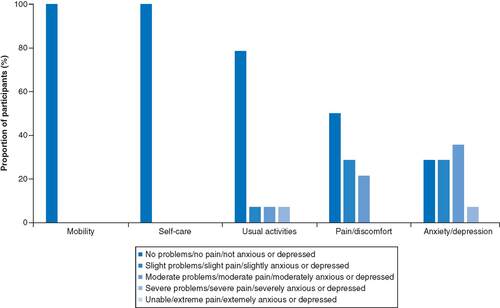

shows the proportion of individuals who responded to each level on each EQ-5D-5L dimension. No participants reported problems with mobility (ability to walk about) or self-care (ability to wash and dress themselves), 79% (n = 11) reported no problems with usual activities (including work, study, household, family and leisure activities), 50% (n = 7) reported no problems with pain or discomfort and 29% (n = 4) reported no problems with anxiety or depression. The mean visual analog scale (VAS) score was 80 (SD: 10.95; range: 50–95) and the mean health utility was 0.816 (SD: 0.161; range: 0.412–1.000), with four caregivers reporting a health utility of 1 (full health).

Background questionnaire

Findings on the time spent caring for the individual with AADC deficiency are shown in . Caregivers reported spending an average of 109.5 h/week (SD: 28.8) on all caring activities combined. Half (n = 7) of the caregivers received unpaid support, which was mainly provided by their partner (mean: 36.7 h/week, SD: 35.8) and 23% (n = 3) received paid support (mean: 26.7 h/week; SD: 14.4). Paid support was funded by the government (n = 2) or was paid out of pocket by the caregiver (n = 1).

Table 2. Hours spent on caring activities per week.

The majority of caregivers reported that their employment had been impacted as a result of their caring responsibilities with 43% (n = 6) having stopped working and 29% (n = 4) having reduced their working hours. In addition, 23% (n = 3) reported that their partners had reduced their working hours. These findings contrast with responses on the EQ-5D-5L where 79% (n = 11) reported no problems with their usual activities and only 7% (n = 1) reported severe problems.

Qualitative data on the EQ-5D dimensions

Mobility

None of the caregivers in this study described any problems with mobility (e.g., walking) when interviewed. Some caregivers indicated that they were physically healthy and able to lift and carry the individual with AADC deficiency and take them for walks in their wheelchairs. All caregivers were therefore categorized as having no problems with mobility based on the qualitative interview data (100%; n = 14). These findings align with the EQ-5D-5L responses, as all caregivers (100%; n = 14) also reported no problems with this dimension on the EQ-5D-5L ().

Self-care

Similar to mobility, none of the caregivers reported any issues with their own self-care (e.g., washing and dressing self) during the interviews (100%; n = 14). These qualitative findings concorded with the EQ-5D-5L responses, as all caregivers (100%; n = 14) also reported no problems with this dimension on the EQ-5D-5L ().

Usual activities

All caregivers reported at least some problems with their usual activities during the qualitative interviews, including their ability to work, study, do housework and take part in family and leisure activities. Caregivers commonly reported that their whole day was focused on providing constant care for the individual with AADC deficiency.

Most caregivers (n = 10) reported that they had needed to make changes to their work, with several reporting that they had to stop working in order to care for their child.

I had to quit my job and stay at home to care for her …I stopped earning money, I stayed at home.” —Participant 301, reported “no problems” with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

“I had to stop working, I used to be in real estate and I had to stop working because he needed a full-time caregiver.” —Participant 605, reported “no problems” with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

“I went from having a job and seeing my people at work, my work and my things, to being constantly in hospitals, rehabilitation clinics and, and with constant care…a total change of life.” —Participant 401, reported “no problems with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

Others described how they had needed to change the type of work that they did to adapt to their new life as a caregiver, although this individual still described how becoming a caregiver had changed their life completely:

I had to change my life completely, my wife as well after he was born. Luckily my past working experiences enabled me to have a freelance type of work.” —Participant 202, reported “no problems with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

Interestingly, all these individuals reported no problems with their usual activities on the EQ-5D. Although some caregivers (n = 4) said their work was not impacted, this was because they were already stay-at-home parents before they became a caregiver to an individual with AADC deficiency.

Some caregivers described how, due to their caring responsibilities, they found it difficult to find time for regular household tasks, including grocery shopping, cooking, cleaning and laundry.

I don't have the time I used to have…I used to do the grocery shopping, I used to love cooking.” —Participant 601, reported “no problems with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

One described how not being able to do these tasks contributed to them having a bad day:

A bad day is where just nothing is working…that's draining because I'm not able to get other things done, to take care of the regular household, you know, laundry, cleaning, cooking” —Participant 604, reported “no problems with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

Again, both of these individuals reported no problems with their usual activities on the EQ-5D.

Several caregivers reported that they needed to plan their time carefully and stick to a tight schedule to fit in all of these responsibilities, which made it difficult for them to make spontaneous leisure or social plans.

You do need to sacrifice a lot. Free time, socialization, going out and doing things…the biggest impact has been that lack of spontaneity and having to have a schedule.” —Participant 606, reported “no problems” with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

“I cannot afford to go fishing for example or going away for the weekend…because anyhow I have this thing first.” —Participant 205, reported “slight problems with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

Some caregivers compared what they could do now with what they used to be able to do before they became a caregiver.

When I was a girl I would go for massages and other things, I liked going to the gym and other things, I was a bit obsessed with the gym but obviously I have no time to do it.’” —Participant 204, reported "severe problems” with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

“I used to have ‘me’ time, hang out with my friends. I used to do, I used to be a yoga teacher. I love fitness, being healthy…I always gave myself time, and now it's very limited.” —Participant 601, reported “no problems with usual activities on the EQ-5D.

These participants described similar experiences, in that both found it difficult for them to find time to exercise and participate in other leisure or social activities. Interestingly, although one of these individuals responded that they had severe problems with their usual activities on the EQ-5D, the other reported no problems. These qualitative findings align with the data from the background questionnaire, where caregivers reported a substantial amount of time spent caring and impact on work. However, they contrast with the EQ-5D-5L responses, where 79% (n = 11) reported no problems with usual activities.

Pain/discomfort

Around a third (36%; n = 5) of caregivers either reported having no problems with pain or discomfort or did not discuss any issues with this during the qualitative interviews. This broadly aligns with the 50% (n = 7) who reported no problems with pain or discomfort on the EQ-5D-5L. However, two caregivers reported no problems with pain or discomfort on the EQ-5D-5L but described suffering from pain and strain on the body from lifting and carrying the individual during the interviews.

He's a little bit more heavy now than he used to be, so that's a little bit more strain on my body.” —participant 602, reported “no problems” with pain or discomfort on the EQ-5D.

“Yes of course, back pain, arm pain.” —participant 401, reported “no problems with pain or discomfort on the EQ-5D.

Anxiety/depression

The majority of caregivers described problems with anxiety or depression during the qualitative interviews (86%, n = 12), which broadly aligned with the 71% (n = 10) who reported at least slight problems with anxiety or depression on the EQ-5D. However, two caregivers reported no problems on the EQ-5D-5L but described how their caring responsibilities affected their emotional wellbeing during the interview. For example, one of these caregivers highlighted their need to speak with a counselor to help them to cope with the constant demands of caregiving and the other described the emotional impact of the uncertainty around the patient's future.

It's a lot to deal with, and that's why I talk to a counselor.” —participant 602, responded “not anxious or depressed” on the EQ-5D.

“It comes down to just the emotional state of it. Just basically… the unknown… I do not know what will happen and what the future holds so emotionally, that's been the biggest… it's just the unknown.” —participant 604, responded “not anxious or depressed on the EQ-5D.

Discussion

This study used mixed methods to evaluate how well the EQ-5D captures the experience of informal caregivers to individuals with AADC deficiency by comparing their EQ-5D scores with qualitative and questionnaire data on the same dimensions. While the EQ-5D and qualitative data were closely aligned on the mobility and self-care dimensions and broadly aligned on pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions, there were large discrepancies between the EQ-5D data and qualitative data on the usual activities dimension. While the majority of caregivers reported no problems with their usual activities on the EQ-5D, all participants reported at least some problems with their usual activities in the qualitative interviews and reported spending a substantial amount of time on caring activities in the background questionnaire.

One explanation for this discrepancy is around the use of the term “usual” activities. The majority of caregivers reported no problems with their usual activities on the EQ-5D despite reporting a substantial impact in the interviews. This does not necessarily mean they were responding inaccurately to the EQ-5D or that the content of the EQ-5D is not relevant, but rather suggests that caregivers' perceptions of “usual” may have shifted over time as they have adapted to the major changes of becoming a caregiver for a severely impaired child. Therefore, while their responses on the EQ-5D may be accurate based on their current usual activities, they do not align with what may be considered “usual” by the general population. While the general population may consider their usual activities to include going to work and participating in leisure activities, caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency may think of their caring responsibilities first. This hypothesis is consistent with data from other studies of caregivers, which have found a similarly high proportion (84%) of caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder to report no problems with usual activities, despite the associated caregiver burden of this condition [Citation24]. Another study conducted among children and adolescents with a range of chronic diseases (including asthma, diabetes and arthritis) found that length of time with the disease was negatively associated with their reported level of problems with mobility and usual activities [Citation25]. This suggests that individuals may adapt to their condition over time and that this may lead them to change perceptions of usual activities [Citation25,Citation26].

Although the EQ-5D and qualitative data were largely concordant for the pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions, it is worth highlighting that some caregivers reported issues in the qualitative interviews that were not captured by the EQ-5D. It is possible that pain/discomfort may be episodic and that the individuals were not experiencing it on the day they completed the EQ-5D. Others may prefer not to label their poor mental health as anxiety or depression, as they perceive there to be a known reason for their emotional state rather than considering it a state of ill health, which may have led to underreporting on that dimension.

Although the discrepancies between the EQ-5D and qualitative data identified in this study can be explained, these findings ultimately highlight an issue with using the EQ-5D to evaluate caregiver HRQoL in AADC deficiency and potentially other populations. This possible failure to capture disutility associated with usual activities may reflect up to a -0.444 difference in utility scores (the difference between “no problems” and “unable to do” usual activities with all other dimensions constant at no problems), based on the EQ-5D-5L crosswalk scoring with UK population weights [Citation27]. Based on the findings of this study, an improvement in a caregiver's usual activities (and in some cases pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) as a result of an effective treatment would not be captured by the EQ-5D, and would therefore be excluded from cost-effectiveness analyses, potentially limiting access to treatments.

Although this study presents case studies in the context of AADC deficiency, these findings may extend to caregivers of individuals with a range of chronic diseases, for example, Alzheimer's disease and multiple sclerosis, as well as to individuals living with chronic or hereditary diseases whose usual activities may be far removed from the societal view of “usual” for an individual with full health. For this reason, the use of the EQ-5D in capturing HRQoL in chronic disease populations, including other chronic neurological diseases, requires further investigation. When the EQ-5D does not adequately capture HRQoL, alternative methods, such as vignette studies, may be accepted by NICE, provided that sufficient evidence is supplied that the EQ-5D is not appropriate [Citation28].

This study had some limitations. The sample size was small, but recruitment is challenging in rare diseases and there was still a clear signal of discordance between the EQ-5D and qualitative interview data. Recruitment was conducted through a specialist recruitment agency and confirmation of the patient's AADC deficiency diagnosis was self-reported by the caregiver, which is less robust than requiring that patients have a clinician-confirmed diagnosis. Nonetheless, caregivers were screened using predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria that provided assurance that participants met the inclusion criteria. Although it was planned for caregivers to be recruited across several countries in Europe and North America, most of the caregivers identified were from the United States and Italy. However, as is the case when researching other rare conditions, recruitment was limited to relying on a best-case scenario due to the extremely low global prevalence of AADC deficiency. A further limitation is the sample was largely white and university educated, which suggests the findings may not be transferable to and may vary in other populations.

Conclusion

The findings of this research suggest that the EQ-5D-5L may not adequately capture quality of life among caregivers of individuals with AADC deficiency, particularly with regard to usual activities. This highlights a potential problem of using the EQ-5D-5L to evaluate caregiver burden in this condition as well as potentially other chronic conditions where caregivers' perceptions of “usual activities” are far removed from that of the general population. This could lead to the benefits of medical treatments being underestimated and, as a consequence, suboptimal decisions from both a healthcare and a societal perspective.

EQ-5D and qualitative data were closely aligned on the mobility and self-care dimensions and broadly aligned on pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions.

There were large discrepancies between the EQ-5D data and qualitative data on the usual activities dimension.

Caregivers' perceptions of “usual activities” may shift over time as they adapt to becoming a caregiver for a severely impaired child.

While caregivers' responses on the EQ-5D may be accurate based on their current usual activities, they do not align with what may be considered “usual” by the general population.

These findings highlight a potential problem with using the EQ-5D to evaluate caregiver health-related quality of life in AADC deficiency, as well as potentially other chronic conditions where caregivers' perceptions of “usual activities” are far removed from that of the general population.

This could lead to the benefits of medical treatments being underestimated and, as a consequence, suboptimal decisions from both a healthcare and a societal perspective.

Author contributions

S Acaster and K Buesch conceived of the study. All authors made a substantial contribution to the design of the study. The study materials were developed by K Williams and H Skrobanski and all authors provided feedback. The English language interviews were conducted by K Williams and H Skrobanski. The analysis was conducted by K Williams and H Skrobanski. S Acaster, K Williams and H Skrobanski drafted the manuscript and all authors provided feedback. All authors approved the final submitted version.

Ethical conduct of research

This study was submitted for ethical review by the WIRB-Copernicus Group Independent Review Board and was granted an exemption (tracking number: #1-1327023-1). All participants provided verbal informed consent to participate at the start of the interviews. All participants provided consent to publish as part of the verbal consent to participate.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the caregivers who took part in the study.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This study was funded by PTC Therapeutics Ltd. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Individual deidentified participant data will not be shared as this is a rare disease, we would prefer not to share the participant-level data to avoid any possibility that the participants could be identified.

References

- KrolM, PapenburgJ, van ExelJ. Does including informal care in economic evaluations matter? A systematic review of inclusion and impact of informal care in cost-effectiveness studies. Pharmacoeconomics33, 123–135 (2015).

- BasuA, MeltzerD. Implications of spillover effects within the family for medical cost-effectiveness analysis. J. Health Econ.24(4), 751–773 (2005).

- WittenbergE, RitterGA, ProsserLA. Evidence of spillover of illness among household members: EQ-5D scores from a US sample. Med. Decis. Making33(2), 235–243 (2013).

- Al-JanabiH, FlynnTN, CoastJ. QALYs and carers. Pharmacoeconomics29(12), 1015–1023 (2011).

- AcasterS, PerardR, ChauhanD, LloydAJ. A forgotten aspect of the NICE reference case: an observational study of the health related quality of life impact on caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis. BMC Health Serv. Res.13(1), 1–8 (2013).

- TilfordJ. NP-E review of pharmacoeconomics, 2015 undefined. Progress in measuring family spillover effects for economic evaluations. Taylor & Francis15(2), 195–198 (2014).

- SteinK, FryA, RoundA, MilneR, BrazierJ. What value health?: a review of health state values used in early technology assessments for NICE. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy4(4), 219–228 (2005).

- ToshJC, LongworthLJ, GeorgeE. Utility values in National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Technology Appraisals. Value Health14(1), 102–109 (2011).

- GoodrichK, KaambwaB, Al-JanabiH. The inclusion of informal care in applied economic evaluation: a review. Value Health15(6), 975–981 (2012).

- PenningtonB, WongR. Modelling carer health-related quality of life in nice technology appraisals and highly specialised technologies [Internet]. http://xn–nicedsu-ixa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2019-04-03-NICE-carer-HRQL-v-2-0-clean.pdf

- NICE. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013 [Internet] (2013). www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/resources/guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf-2007975843781

- NICE. NICE health technology evaluations: the manual [Internet] (2022). www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg36/chapter/introduction-to-health-technology-evaluation

- HerdmanM, GudexC, LloydAet al.Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res.20(10), 1727–1736 (2011).

- EuroQoL Group. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy16(3), 199–208 (1990).

- SolemCT, Vera-LlonchM, LiuSet al.Impact of pulmonary exacerbations and lung function on generic health-related quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes14(1), 63 (2016).

- JanssenB, SzendeA. Population Norms for the EQ-5D. In: Self-Reported Population Health: An International Perspective based on EQ-5DSpringer, The Netherlands, 19–30 (2014).

- PoleyMJ, BrouwerWBF, Van ExelNJA, TibboelD. Assessing health-related quality-of-life changes in informal caregivers: an evaluation in parents of children with major congenital anomalies. Qual. Life Res.21(5), 849–861 (2012).

- PearsonTS, GilbertL, OpladenTet al.AADC deficiency from infancy to adulthood: symptoms and developmental outcome in an international cohort of 63 patients. Wiley Online43(5), 1121–1130 (2020).

- WassenbergT, Molero-LuisM, JeltschKet al.Consensus guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency. Orphanet J. Rare Dis.12(12), 1–21 (2018).

- WilliamsK, SkrobanskiH, WernerC, O'NeillS, BueschK, AcasterS. Symptoms and impact of aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: a qualitative study and the development of a patient-centred conceptual model. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.37(8), 1353–1361 (2021).

- FettersMD, CurryLA, CreswellJW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs - Principles and practices. Health Serv. Res.48(6 PART2), 2134–2156 (2013).

- SkrobanskiH, WilliamsK, WernerC, O'NeillS, BueschK, AcasterS. The impact of caring for an individual with aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency: a qualitative study and the development of a conceptual model. Curr. Med. Res. Opin.37(10), 1821–1828 (2021).

- van HoutB, JanssenMF, FengY-SSet al.Interim Scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: Mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L Value Sets. Value Health15(5), 708–715 (2012).

- BrownCC, TilfordJM, PayakachatNet al.Measuring health spillover effects in caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder: a comparison of the EQ-5D-3L and SF-6D. Pharmacoeconomics37(4), 609–620 (2019).

- OttoC, BarthelD, KlasenFet al.Predictors of self-reported health-related quality of life according to the EQ-5D-Y in chronically ill children and adolescents with asthma, diabetes, and juvenile arthritis: longitudinal results. Qual. Life Res.27(4), 879–890 (2018).

- Ravens-SiebererU, ErhartM, WilleN, WetzelR, NickelJ, BullingerM. Generic health-related quality-of-life assessment in children and adolescents: methodological considerations. Pharmacoeconomics24(12), 1199–1220 (2006).

- van HoutB, JanssenMF, FengY-Set al.Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health15(5), 708–715 (2012).

- NICE Decision Support Unit. Measuring and valuing health-related quality of life when sufficient data is not directly observed (2022). https://nicedsu.sites.sheffield.ac.uk/methods-development/measuring-health-related-quality-of-life