Abstract

Aim: To explore primary care physicians’ views of the utility and delivery of direct access to pharmacogenomics (PGx) testing in a community health system. Methods: This descriptive study assessed the perspectives of 15 healthcare providers utilizing qualitative individual interviews. Results: Three main themes emerged: perceived value and utility of PGx testing; challenges to implementation in practice; and provider as well as patient needs. Conclusion: While providers in this study viewed benefits of PGx testing as avoiding side effects, titrating doses more quickly, improving shared decision-making and providing psychological reassurance, challenges will need to be addressed such as privacy concerns, cost, insurance coverage and understanding the complexity of PGx test results.

Background

Pharmacogenomics (PGx) testing has the potential to personalize medication management for a wide range of patients [Citation1]. More than 160 medications currently have PGx labeling from the US FDA, ranging from heart disease medications to psychiatric drugs [Citation2]. Identifying genetic variants associated with response to medication may benefit patients for more accurate drug dosing and selection in order to optimize responses and/or to avoid unwanted side effects [Citation3,Citation4].

Given the wide reach of PGx and a shortage of genetic professionals to handle the potential volume, primary care physicians are in a front-line position to review and explain findings to patients from PGx tests [Citation5,Citation6]. Guidelines have become available for a number of medications with applicable PGx testing through the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium [Citation7–9]. Although physicians may perceive a benefit to using PGx [Citation3,Citation5,Citation9–12], many barriers exist that have prevented implementation on a larger scale such as: physicians lacking sufficient knowledge and finding time to keep up-to-date; uncertainty surrounding clinical utility; lack of confidence or comfort in ordering PGx testing; lack of comfort interpreting results; uncertainty in how to communicate results to patients and having sufficient time to do so; difficulty in managing changes to workflow; determining how to incorporate results into the electronic medical record (EMR); and uncertainty about level of coverage by insurance and reimbursement [Citation3,Citation5,Citation6,Citation9–15].

While various studies have investigated physician knowledge, opinions, comfort level and preparedness for using PGx testing in practice, questions remain regarding the best delivery method of PGx testing and reporting results [Citation16]. Implementation of PGx has been attempted in a variety of settings and using various methods. A multidisciplinary clinic approach utilized medical geneticists, pharmacists, an advanced practice nurse and genetic counselors [Citation17]. Although this model provides the patient a thorough evaluation of the pharmacogenetic variants they are found to carry, such effort lacks scalability to be an efficient sole implementation effort for a health system. Pharmacist-delivered medication management demonstrated feasibility and satisfaction from patients; however, overcoming barriers of continued education and reimbursement still need to be addressed [Citation18]. Other pharmacist-assisted methods have been implemented in community pharmacies which proved feasible and took little time, but patient understanding and satisfaction were not investigated [Citation16]. Clinical decision support methods have been employed in some primary care practices; however, physicians may not always know how to utilize and incorporate pharmacogenomics decision alerts in their medical decision-making [Citation19]. In one study, only 30% of physicians receiving the alert were inclined to make a change in prescription based on the specific alert, and in another study physicians reported disagreement about who should be responsible for receiving results and providing patient follow-up [Citation10,Citation20].

One new pharmacogenomics testing model that has not been investigated is direct access testing. This type of service utilizes provider-ordered PGx testing which involves mailing a testing kit to the patient and returning results in a manner that the provider typically uses (telephone, in-person, mail, etc.). Through this process, PGx testing can be completed at home by the patient, but still involves supervision from the ordering healthcare provider. This is distinct from direct-to-consumer testing where a healthcare provider does not need to be involved in the process [Citation1,Citation21–23]. Increased access to health information on the internet, demand for personal healthcare autonomy and lower test costs have likely increased the demand for these services – as healthcare has become more consumer-driven [Citation22]. However, controversy remains regarding potential risks and benefits of consumer-driven access to genomic information [Citation1,Citation21,Citation23]. Concerns have been raised such as individual misunderstanding and anxiety, potential use of unnecessary health services and acting on information without the input of a health professional [Citation1,Citation21,Citation23]. Some studies have shown that only 25–35% of individuals report having shared their PGx direct-to-consumer test results with their physicians [Citation1,Citation24,Citation25]. In one study, only 7% of physicians reported having seen a patient’s direct-to-consumer test result [Citation22]. These findings highlight an important communication gap between patients and their physicians. Direct access testing is a new concept to clinical PGx that aims to decrease this gap while maintaining patient autonomy.

Very little is known about how primary care physicians view the use of direct access PGx services in their practices. Information is also lacking about how well prepared they feel in order to interpret test results that their patients receive from PGx testing. This paper reports on findings of a study to explore primary care physicians’ views of the utility and delivery of direct access to PGx testing in a community health system.

Methods

Study participants & setting

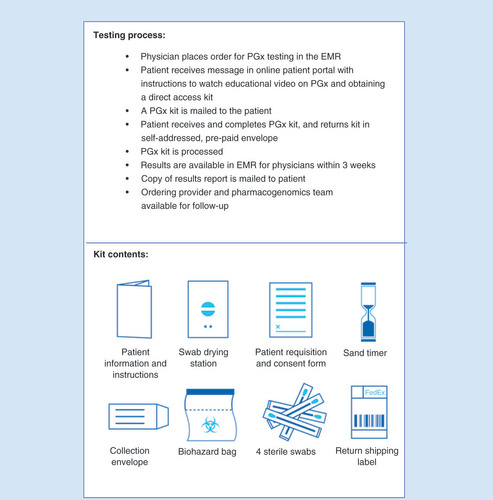

Study participants were NorthShore University HealthSystem primary care physicians who received complimentary pharmacogenomics direct access kits through a pilot program. Physicians underwent PGx testing themselves and received results. They also received complimentary PGx kits for their patients. Once an order for PGx testing was placed, the direct access process included watching an online educational video, completing a requisition form and buccal swab at home and mailing in the sample to the laboratory (). Results were sent by mail to both the participating physicians and their patients who had complimentary testing. PGx test results were also available to the physician in the EMR. The intent of the pilot program was to increase physician understanding of the direct access process as well as PGx in general. NorthShore University HealthSystem is a four-hospital community health system in north suburban Chicago with over 100 physician offices. A purposive sampling plan included identification of pilot program primary care physicians practicing in a range of practice settings and locations in the health system. Participants were recruited by email from six primary care practice pilot sites located in the service area. Participants received compensation for their time with a $150 service award. This study was reviewed and approved by NorthShore University HealthSystem’s institutional review board.

Data collection

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were chosen as a method of eliciting data from participants – to allow for clarification of viewpoints, discovery of unanticipated findings and as a strategy to learn more about the rationale behind primary care physician PGx clinical decision-making. Audiotaped individual interviews were conducted during December 2016 and January 2017. The interviews lasted approximately 30 min each and were conducted in-person at the primary care practice site or via telephone, depending on participant preference. Interview data were analyzed on an ongoing basis until saturation of themes, or no new emerging major constructs, occurred. Saturation was reached after 15 interviews, which falls within the reported range for this type of qualitative study approach [Citation26]. Trained interviewers used a discussion guide consisting of nine open-ended questions, and probes, directly relating to the study’s objectives (Supplementary Material 1). A brief background survey was administered at the end of the interview, to gather demographic information. The interview guide was pretested through five cognitive interviews with primary care physicians practicing in the NorthShore University HealthSystem, and revisions were made based on suggestions from these interviewees, as well as from internal and external expert reviewers [Citation27].

Data analysis

Interview discussions were transcribed and independent checks, by two investigators, confirmed accurate and verbatim transcription. Transcripts were uploaded into Atlas.ti (version 7.0), a qualitative data management and analysis software program. This type of software can create a document system to store and retrieve coded text, search for words and phrases in the text, and create an index system to link categories and data [Citation28]. The discussion guide was first used to develop a provisional list of codes. These codes were refined and changed as new ideas were encountered in the reading of each interview transcript. A final codebook of 18 codes, with definitions and quotation examples, was utilized by the investigators to identify key opinions and themes. Two investigators independently coded each transcript and worked collaboratively to resolve any coding discrepancies. Grounded theory was used as a general guide to allow themes and theory to emerge from the transcript data [Citation29]. The themes were collectively explored and interpreted by the research team. Data reduction and analysis were conducted through standard qualitative methods of coding, notation and theme identification [Citation30].

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 15 primary care physicians, from six practice sites, participated in this study. Slightly more than half (60%) were females and all participants spent 51% or more time in patient care. The majority (73%) specialized in internal medicine, and their years in practice varied from less than five to greater than 21. Participants had undergone PGx testing themselves and most (80%) of the physicians had ordered between one and five PGx testing kits for their patients.

Interview findings: themes

Based on investigator team analysis of the qualitative interview data, three broad themes were identified regarding views toward direct access PGx testing: perceived value and utility; challenges to implementation in practice; and provider as well as patient needs going forward. Each of these broad themes included sub-themes of related concepts. The themes and sub-themes are described, along with exemplary quotes from the primary care interview transcripts.

Value & utility

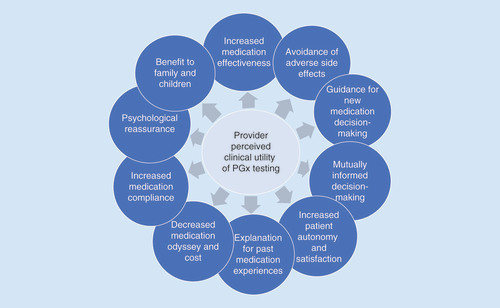

Value and utility of direct access PGx testing was one of the key themes that emerged, and participants described these concepts in a number of ways. Two sub-themes describing value included how test findings can be used to guide primary care decision-making in particular contexts, and how information from testing can lead to specific positive outcomes for patients.

Guiding primary care medical decision-making

Most participants felt that undergoing direct access PGx testing themselves was a useful teaching tool and that it was helpful for them to have first-hand knowledge of the testing and resulting process. To them, this translated into providing better and more concrete information to patients regarding testing and decision-making. One of the participants (P14) described his PGx testing experience with the take-home kit: “Oh, it is very useful. It was easy. And when I’m explaining it to patients I tell them exactly how to do it, not, ‘You’ll get a kit and then the instructions will be there’. I tell them, ‘You’re going to swab for thirty seconds here, thirty seconds there, a minute over here. You’re going to let it [the sample] dry’. I give them the full details”. This provider discussed how going through his own PGx testing and results process was helpful to him in explaining patient results. He said: “I was my own test case, so I think that was a very good way to introduce physicians to this process, to actually do it. When you do it, you certainly learn a lot more. Then, you go through the report. Certainly makes it easier for me to explain a patient’s report when I have seen my own”.

Primary care physicians described how PGx testing could help them individualize medication treatments for their patients and, for many, how there is a context-dependent value for specific conditions or categories of patients. The most common indications for offering PGx testing that physicians mentioned were for medications used in psychiatry, cardiology, oncology and for pain management. One provider (P12) reported: “I think it will be specific to certain patient populations…patients that I see that’ll benefit from it are probably patients that are on some psychiatric drugs, antidepressants, SSRIs are a big one”. Another participant (P14) described how having results from PGx testing could be beneficial in his patient population: “One of the most valuable parts of this [testing] I think is the blood thinner. That’ll be very valuable if they’re in the emergency room getting a stent and the decision is trying to be made as to which blood thinner they get put on. I think they are going to benefit tremendously from that bit of information”.

Another general area discussed regarding the utility of PGx testing was helpfulness to patients in potentially avoiding medication side effects and guiding decision-making for patients who are starting a new medication. One participant (P04) related his thoughts about PGx testing for his patients: “I think of patients who’ve had difficulties with different medications, classes of medications, and potentially utilizing this information to prevent using time poorly in terms of starting patients on medicines that probably won’t work or putting them on doses that probably won’t work”. Another participant (P07) said: “It will help me decide what medication to give to the patient, say if it’s a patient with depression that I’m having a hard time figuring out what medication I could use due to side effects or lack of response”. Some primary care physicians indicated that they had a number of patients who are highly motivated to learn more about their health in general, and that these individuals would likely be interested in testing. One physician mentioned pre-emptive testing and how PGx testing could be offered during an annual exam. Another primary care physician (P01) articulated how through PGx testing, a mutual benefit of informed decision-making can occur for both physician and patient: “I think it can help both physician and patient make informed decisions together, based on likelihood of responding poorly to medications -based on the genetic profile”.

Improving patient outcomes

Another value of PGx testing described was specific positive outcomes for patients. For example, some of the physicians discussed how using PGx direct access testing can foster increased patient autonomy and satisfaction. One provider (P09) stated: “…the patients, if they’re interested, they can just go ahead and initiate it themselves [after physician places the order, patients do the test kit when and where convenient] and that just opens up doors and decreases the barriers”. In addition, participants cited specific examples of how PGx testing results were used to adjust patient medications to increase effectiveness and reduce side effects. A practitioner (P11) explained: “His results showed that Plavix was not likely to be beneficial to him, so it affected, actually, his treatment plan”. Another interviewed physician (P15) detailed her patient’s outcome: “Yeah, he’s been struggling with depression. He’s been very against medication, antidepressants specifically. A lot of anxiety related to side effects. He went on Lexapro and after two days he had horrible, horrible side effects that took a week to ease off of, mostly GI-related. You hit that point where you finally get him to the threshold, and all the things he was afraid of happened…But now [after PGx test results] he’s on Effexor, and a month later he’s a totally different person”.

A number of primary care physicians talked about the complicated dynamics that occur when patients try medications that either do not work or cause adverse effects. Patients may or may not want to embark on another medication trial and one physician (P05) talked about how PGx testing could be used to improve patient compliance in these situations: “…like my patients who are on antidepressants, cholesterol medications-we can actually do the testing and find out which medications either work the best or produce the least side effects. And then hopefully that would lead to better compliance. That’s the problem with all these medications-nobody takes them”. Participants discussed the medication odyssey that some patients embark on before they have a successful outcome and that this process can cause suffering, harm and increased costs to the patient. Physicians mentioned how PGx testing could make this process of medication decision-making for some patients much more efficient and save them from having to suffer and incur additional costs. One primary care doctor (P08) elucidated: “A lot of times we try a medicine and they’re only on it for two weeks, and they paid for a whole month. They’re only on it for two weeks and they had horrible side effects. Let’s toss that and move onto something else. That’s a lot of money, and time, and side effects that they don’t necessarily need to suffer from if we knew ahead of time that they weren’t going to react well to it”.

Another positive outcome mentioned by some of the primary care providers was psychological benefit to patients. A few physicians discussed how findings from PGx testing can offer reassurance that the medication plan should either stay the same or be changed. Test findings were described as having important explanatory benefits for patients, who were searching for reasons of why medications worked or did not work so well. One physician (P13) brought up how PGx findings allowed the patient to have less fear and anxiety about trying a new medication: “The reassurance to me is key and there’s a psychological benefit. If I knew that drug A would be better for me than drug B, there’s a psychological component to saying, ‘Okay, my doctor knows that drug A is going to be effective for me or that it’s not going to be harmful for me’. Both for the patient’s reassurance and certainly for mine”.

Pharmacogenomic results were also described as a potential benefit to family members, including children. One primary care physician (P15) remarked about a patient: “every pain medicine that I could think of - fentanyl, Dilaudid, morphine, hydrocodone, oxycodone -showed that he’s unlikely to respond to the typical doses. And then that [PGx results] made sense in response to his experience. He had broken his hip when he was eight and was on the unit for days, and he remembers having to be moved into isolation because he was screaming so much, because he was constantly in pain. The morphine would wear off after like 30 minutes. So my thought, our thought, is good chance he was being dosed appropriately for a pediatric patient, but [actually] much less than what he needed. It was nice to see that there was a reason behind that, probably. I think traditionally, we think of this [PGx testing] as helpful for adults, but in this particular instance, like a kid having to deal with pain for a broken bone - because they actually need a lot more medication. Most doctors would be really cautious about not overdosing with narcotics. It’s just something that would be helpful to take into account”.

Although the majority of participants described value and utility of PGx testing in positive terms, a few providers mentioned that they did not think PGx testing was useful in their patient population and/or that PGx testing may not be useful now but will be more valuable in the future. For example, one practitioner (P13) commented: “For the general population, who is not going to be on pain meds or any of the antidepressants, anti-anxiety agents, I’m not sure how beneficial it’s going to be”. However, one provider (P12) speculated that its future utility may increase: “But in the future, maybe every patient, it could be offered to them”.

Challenges to implementation in practice

For providers

Challenges to implementation in practice were reported by participants, including both to themselves as well as to their patients. One of the main hurdles for providers was difficulty in understanding the pharmacogenomics test report. A desire for content clarification on the results report was mentioned and some preferred certain formats for results display as well as a paper copy of the results. A delay (beyond typical 3 weeks) in receiving results was also described as a barrier in providing timely patient feedback. Difficulty with accessing the results report within the EMR was also mentioned. One physician (P02) articulated his challenges: “So, I’ve been having problems. I really have not received anybody’s clinical results, as far as a notification goes, that it’s ready. I get the results of their phenotyping only and then later on I’ll find that the clinical [result] has been sitting there and it’s back, and it never comes at the same time. It comes later and it doesn’t alert us to when those results are populated”.

Many of the participants described having a lack of understanding of how to interpret the pharmacogenomics results and that they were not adequately prepared to communicate complex results. One physician (P05) shared that he felt: “Less comfortable. You know, looking at some of the results that were returned, that just kind of says ‘drugs to avoid’, but doesn’t give a lot of science behind it or explanation. I think I would like some guidance with that”.

One of the perceived barriers to uptake of PGx testing in their practices was high cost and lack of reimbursement. A participant (P12) stated: “…maybe the cost for some patients. If it’s not covered by insurance, it might be a bit much and patients may not have so much buy in to it if they don’t think it is really going to be a benefit”. Another practitioner (P15) commented about test benefit and justification for insurance coverage: “Then of course that becomes a challenge of what you have to prove to them [insurance companies] in order to show them that a patient would benefit in order for them to cover. Are there any instances where insurance companies cover, can you answer that, or no?”

Although most primary care physicians mentioned that the workflow process utilizing direct access PGx testing worked well in their practices, they brought up time constraints as a challenge and the need for an in-office follow-up appointment to discuss results. One physician (P08) noted: “A lot of times when people think genetic testing, they think this is going to show them that they’re going to get cancer or whatever. We have limited time to be explaining this along with everything else that we talk about in our exams”.

For patients

The barrier to PGx testing that was most often discussed by participants was the cost to their patients. An interviewed provider (P11) said: “I don’t think that any patients are really going to pay for that unless there’s really, truly a concern. You know, if someone’s tried multiple statins or multiple antidepressants and even then it’s hard for them, it’s going to be hard to convince someone to do this test that’s not covered. I think it’s different from paying out of pocket for a heart scan because it’s such a visual thing and people totally get it. I mean, we’ll see with time how it goes”. Another primary care physician (P10) related a patient’s reaction to not receiving significant clinical results from pharmacogenomic testing in regards to cost; he recalled: “I know one person felt shortchanged that they did this test and they didn’t get any information from it”.

A number of physicians described how concern with data and privacy could be a challenge for patient uptake of PGx testing. One provider (P11) commented on concerns patients may have about protection of their genetic information from the government: “I think people get concerned when they’re sending their cheek cells off that their DNA is getting sent in the mail and they don’t know what’s actually truly happening to it, and people think that maybe they’re getting cloned or finding out genetic information that’s going to come back and hurt them in the future in some ‘Brave New World’ situation where the government is tracking our genetic codes and that can harm them in some way. I think that’s nonsense, but I know that’s how some people think”. Another practitioner (P14) mentioned patient privacy concerns and insurance company access to their test information: “But they may bring that up and say, ‘Is this going to be available to insurance companies? And am I going to be rated higher because I have a certain profile?’”

The need for flexible testing options was described by physicians, in order to meet the needs of diverse patients. One physician (P04) described how technical issues could be an obstacle and that some patients might not be able to navigate the technical arena of going online to watch an educational video and submit payment; he stated: “I just think some people are not technologically savvy and a simple thing, simple things become huge obstacles”. Having to mail in the test kit via FedEx was also mentioned as a barrier for some patients. A participant (P06) discussed how she might have to guide an elderly patient through the process, or that she might want to do the kit testing in the office setting, rather than have the patient do it at home. This primary care physician said: “I actually took the kit to my patient and did the testing, because she happens to be somebody I also know, and I think if I hadn’t been there, she might have been a little rattled doing it. She’s a little older and taking care of a variety of different medical problems at once”.

One of the findings that emerged was the concept of managing results expectations with patients. A practitioner (P02) articulated the importance of this discussion with patients: “And, you know, it’s again, this test doesn’t encompass all drugs yet either, so you can’t use it as the ace in the hole, so to speak, that it’s going to get you out of trouble every time. It’s just one aspect of the patient that you’re analyzing that will hopefully yield some benefits for that patient. It’s not going to be 100% of the time where you’re going to have a successful outcome, but it’s probably got limited or no downside to hurt the patient”. Another physician (P13) commented on managing patient expectations; she stated: “Not as long as you set the expectations. I think you can’t bill it as, ‘We know exactly what drug to use and how much to use,’ but we can say, ‘It’s a guide’. So setting those expectations, because if you don’t set the expectations and they’re saying, ‘How come this didn’t work for me?’ It’s just a guide. It’s not all the answers. Also, the expectation of really what drugs we’re looking at. Making sure that they’re clear with that. That it’s not like in a test for breast cancer risk or things like that, so it’s always setting the expectations”.

In addition to managing patient expectations about what kinds of information PGx testing can and cannot provide, one participant also brought up a patient’s concern about potentially not being able to use a certain medication. This primary care physician (P08) described a patient who required additional reassurance after receiving her results: “I had one patient that reacted only more in panic. All the things that were red-flagged like ‘Never take Plavix, never take this’. More ‘what if I need it? What do I do then?’ You’re 30, you don’t need Plavix, but one day when you do, hopefully there’s a drug out there that you can use instead. I only had one patient that reacted more alarmist, anxious, about the results, and was not as thrilled that she got them”.

Needs going forward

Participants also mentioned specific needs that they would like addressed going forward. In essence, they provided us with a wish list. This list spanned from needing more PGx education to guidance on how to address cost and insurance issues with patients. When describing PGx education needs, many different modes of training were suggested such as in-services, case studies, and online training. For example, one participant (P02) mentioned: “I think it would be nice to have more in-servicing or more education on what all those things mean and why. I know there’s a clinical scenario and that’s important too, but I think a little bit more of the background into it would be helpful for physicians who are ordering this, so they really feel comfortable, not only with the clinical interpretation, but really understanding a little deep analysis of what that means for that patient. So, you know, I would like I think a little more education –[that] would even be that more valuable for clinicians”. One participant wanted further training specific to results report interpretation. She (P03) asked for an explanation to detail: “Say, ‘here’s the genes that we’re going to be showing you, here are the ones that are relevant, here’s what you tell the patients about these other ones that are irrelevant. And if you have trouble with this, you know, here’s a resource for them and for you.’” Another physician (P09) volunteered: “Maybe even if someone just sat down and reviewed my results with me, that would give me an idea of how to present it to a patient, or how to explain it to a patient, if someone treated me like a lay-person and read through my results and showed me how they would do it”.

Along with the various modes of trainings participants mentioned, they also were interested in receiving both provider and patient education materials. One participant (P09) example included: “I think for patients it would be nice if we had pamphlets, nice, colorful, good pamphlets, that we could put in the office that patients can grab and look at themselves, because that would help them initiate testing. I don’t know how much having meetings and things like that will help, but definitely having a step-wise thing, how to order it. You know, ‘this is how to order. This is what you do with the results’.”

A specific need mentioned by participants was potential changes in the results report to make it clearer. One participant (P03) said: ‘No, it [specific genetic/metabolic details] could all be on the back end of the report, but I need the first page to be much more clinically relevant”. One other area of need was regarding how to address PGx test cost (∼$400) and insurance coverage with participants. Currently, insurance does not cover most pharmacogenomic testing. One physician (P15) suggested: “Any additional info on helping those patients potentially get that test covered. Giving specific instructions, ideally printed, to say this is the cost, if it’s not covered, what can you do to try to get it covered, or at least to be able to apply it to your insurance office, because that is the second primary question that most patients ask. Most will still balk at $400. I think $100 or $200, a lot more patients would come around to”.

Discussion

This report describes perspectives of primary care physicians in a community-based hospital system providing direct access PGx testing to their patients. Physicians expressed their views on the value and utility of PGx testing to help guide decision-making and improve patient outcomes. An important measure of the value of a genetics, or innovative, test is clinical utility [Citation31]. However, when strong evidence is lacking, as in the case of some of the pharmacogenomics tests, incorporating key stakeholders’ perspectives, and the specific context, is helpful in determining current value of testing [Citation32–34].

Previous studies on views of the utility of PGx tests, from the perspective of primary care providers, have reported on value due to more accurate medication dispensing, decreasing adverse response to medications, improving medication effectiveness, and providing additional guidance for prescribing new medications [Citation5,Citation10]. According to another study, physicians found utility in providing PGx testing to improve patient outcomes by individualizing treatment to guide medication decisions and to decrease time and cost for maximizing the benefits of needed medications [Citation35]. Utilizing PGx testing in order to avoid side effects from medication and improve medication effectiveness have been proposed as benefits in other studies as well [Citation5,Citation17,Citation20,Citation35–37].

While many stakeholders have described the benefits and utility of PGx testing in terms of personalizing medication prescribing, our qualitative study revealed that participants had additional views of PGx test value and utility. For example, primary care physicians in this study broadened the more traditional concept of ‘clinical utility’ of PGx testing to include factors such as improving medication compliance, psychological reassurance for providers and patients, validation of and explanation for past medication experiences, increased patient autonomy and satisfaction, and benefit to other family members (). In addition to the concepts of clinical utility of PGx testing described by the study physicians, they also mentioned testing as beneficial to specific populations, such as patients being seen for psychiatry, cardiology, oncology and for pain management, as well as for patients highly engaged in their healthcare. Providers also described a medication ‘odyssey,’ referring to time required for a trial-and-error approach to medication management until finding an effective and safe medication. All of these factors described as aspects of clinical utility, value and benefit are important to consider in informing effective clinical PGx delivery.

The ability of the primary care practitioners to have personal experience going through the direct access PGx testing process was described as beneficial through experiencing the process of using the kit and receiving and reviewing their own results. In order for PGx testing methods to be most effective, stakeholders, such as physicians, will need to better understand the process themselves in order to provide recommendations of such testing to their patients [Citation20,Citation35]. Other studies conducted with medical, graduate and pharmacy students who underwent personal genomic testing, which included PGx-related data, also revealed that this testing provided insight into the patient experience and increased understanding of genetic concepts [Citation37–40]. Another study of physician assistant students who were specifically offered CYP2D6 testing reported similar results and noted that further exposure to PGx testing during rotations influenced perceptions of clinical utility as well [Citation41]. Physicians in our study similarly commented on the benefit of undergoing personal PGx direct access testing to better appreciate the patient experience; however, many participants remarked that they need further education to increase understanding of PGx-related concepts.

In addition to positive aspects of PGx testing, participants relayed challenged they encountered. Physicians described the need for more understandable result reports for both themselves and their patients and less delay in receiving results. Previous studies have reported physicians’ views on their lack of preparedness in interpreting and providing recommendations based on PGx results to their patients [Citation9,Citation20]. Modifications have been made in response to these concerns; result reports were revised to be more clear, concise and patient-centered. A new summary chart was added to the report that includes every medication with a well-established PGx interaction for the patient. An example report and instructions are now available on a website along with answers to frequently asked questions and links to informational resources and educational materials. The delay in physicians receiving results was a result of unfamiliarity; therefore, methods for finding results were clarified within the electronic medical record. Time constraints for providing medications in an emergent scenario make it difficult for patients to utilize PGx testing, which is due to the length of time it requires for the sample to be analyzed and resulted [Citation35]. However, some argue that pre-emptive PGx testing may be a way to mitigate this concern [Citation42]. Physicians also described test cost incurred by the patient (as many insurance companies will not cover testing) as one of the most significant barriers to PGx testing. Several other studies have highlighted cost as a barrier as well [Citation15,Citation35,Citation43,Citation44]. Following this feedback, this health system implemented cost strategies that make pricing more accessible to patients. Further research will need to be done to determine acceptability of the reduced cost.

Many of the aforementioned challenges have begun to be addressed within this healthcare system; in addition, physicians expressed several areas of future need. Assistance with addressing cost and insurance coverage with patients was requested. Additionally, education for providers and materials to assist both the provider and the patient through the testing process, and receiving results, were identified as other areas to address. Previous studies have identified a similar need and various educational resources have been made available online [Citation42,Citation43]. Although this study provides insight into how physicians view the direct access PGx test delivery model, further research will be needed to assess the patients’ perspectives of this model, including perceived benefits and challenges.

Study limitations

This was an exploratory study to assess physicians’ experiences with pharmacogenomics testing. However, the small sample size may not fully represent the opinions of physicians within the primary practice sites selected, nor held by primary care physicians as a whole, thereby limiting generalizability. Further quantitative studies will be helpful in evaluating whether these opinions are more universal among other primary care physicians and specialists. During semi-structured interviewing, the manner in which interviewers ask questions of participants has the potential to introduce bias to responses. However, the semi-structured questions were designed to elicit open-ended responses and allow the participant to respond to the questions in a manner that has relevance to them. This allows for more varied responses and for new or additional information to emerge. Given that the test kits were complimentary for the participants, it’s possible that individuals who would have to pay for the test would hold different opinions on the utility and benefit of the test.

Conclusion

Physicians in this study expressed views on the value and utility of PGx testing to help guide decision-making and improve patient outcomes. While providers viewed benefits of PGx testing as avoiding side effects, titrating doses more quickly, and improving shared decision-making; they also discussed areas of concern and future need, such as addressing cost, insurance coverage and complexity of PGx test results. Within this health system, perceived concerns and needs have started to be addressed, including the reduction of test cost, clarification of result reports and increased educational opportunities on PGx. Future studies will need to assess a larger sample of physicians’ and patients’ perspectives on the value and utility of direct access pharmacogenomics testing.

Value & utility

Primary care physicians saw value in undergoing the pharmacogenomics (PGx) direct access test process for providing first-hand knowledge of the testing.

Physicians expressed the value of PGx direct access testing as an aide to individualize treatment and to guide mutual medical decision-making.

Participants expressed support for various areas of utility of PGx testing to improve patient outcomes.

Providers discussed additional areas of utility, including increased patient satisfaction and other psychological benefits, and benefits to family members and children.

Challenges to implementation in practice

Physicians discussed provider challenges to implementing PGx direct access testing: understanding and communicating the pharmacogenomic test result report; educating patients; costs to patients; and time constraints.

Practitioners noted areas of concern for patients in PGx direct access testing: cost; data privacy; and technological barriers.

Needs going forward

Primary care physicians expressed the need for increased provider education, offered through a variety of modalities.

Providers also requested: clarification of the PGx results report; patient and provider educational materials; and assistance addressing cost and insurance coverage with patients.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. This investigation received a waiver of in-person consent per the institutional review board; implied consent was received via participant email invitation acceptance.

Supplemental Document 1

Download MS Word (12.9 KB)Supplemental Document 2

Download MS Word (35.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of KL Kaul; DL Helseth Jr; K Gulukota; and the NorthShore University HealthSystem Molecular Genetics Laboratory for their essential contributions in the delivery of clinical pharmacogenomics. They especially thank the physicians who participated in this study.

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2217/pme-2017-0036

Financial & competing interests disclosure

P Hulick receives financial compensation as an Up-To-Date topic author on the subject of “Principles and clinical applications of next-generation DNA sequencing”. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- van der Wouden CH , CarereDA , Maitland-van der ZeeAH , RuffinMT , RobertsJS , GreenRC . Consumer perceptions of interactions with primary care providers after direct-to-consumer personal genomic testing . Ann. Intern. Med.164 ( 8 ), 513 – 522 ( 2016 ).

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration . Table of pharmacogenomic biomarkers in drug labeling ( 2017 ). www.fda.gov/Drugs/ScienceResearch/ResearchAreas/Pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm .

- Stanek EJ , SandersCL , TaberKAet al. Adoption of pharmacogenomic testing by US physicians: results of a nationwide survey . Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.91 ( 3 ), 450 – 458 ( 2012 ).

- Zhang G , NebertDW . Personalized medicine: genetic risk prediction of drug response . Pharmacol. Ther.175 , 75 – 90 ( 2017 ).

- Haga SB , BurkeW , GinsburgGS , MillsR , AgansR . Primary care physicians’ knowledge of and experience with pharmacogenetic testing . Clin. Genet.82 ( 4 ), 388 – 394 ( 2012 ).

- Selkirk CG , WeissmanSM , AndersonA , HulickPJ . Physicians’ preparedness for integration of genomic and pharmacogenetic testing into practice within a major healthcare system . Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers17 ( 3 ), 219 – 225 ( 2013 ).

- Caudle KE , KleinTE , HoffmanJMet al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process . Curr. Drug Metab.15 ( 2 ), 209 – 217 ( 2014 ).

- Relling MV , KleinTE . CPIC: clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium of the pharmacogenomics research network . Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.89 ( 3 ), 464 – 467 ( 2011 ).

- Unertl KM , FieldJR , PriceL , PetersonJF . Clinician perspectives on using pharmacogenomics in clinical practice . Per. Med.12 ( 4 ), 339 – 347 ( 2015 ).

- St Sauver JL , BielinskiSJ , OlsonJEet al. Integrating pharmacogenomics into clinical practice: promise vs reality . Am. J. Med.129 ( 10 ), 1093 – 1099 ( 2016 ).

- Haga SB , TindallG , O’DanielJM . Professional perspectives about pharmacogenetic testing and managing ancillary findings . Genet. Test. Mol. Biomarkers16 ( 1 ), 21 – 24 ( 2012 ).

- Dickmann LJ , WareJA . Pharmacogenomics in the age of personalized medicine . Drug Discov. Today Technol.21–22 , 11 – 16 ( 2016 ).

- Haga SB . Challenges of development and implementation of point of care pharmacogenetic testing . Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn.16 ( 9 ), 949 – 960 ( 2016 ).

- Johansen Taber KA , DickinsonBD . Pharmacogenomic knowledge gaps and educational resource needs among physicians in selected specialties . Pharmgenomics. Pers. Med.7 , 145 – 162 ( 2014 ).

- Rosenman MB , DeckerB , LevyKD , HolmesAM , PrattVM , EadonMT . Lessons learned when introducing pharmacogenomic panel testing into clinical practice . Value Health20 ( 1 ), 54 – 59 ( 2017 ).

- Moaddeb J , MillsR , HagaSB . Community pharmacists’ experience with pharmacogenetic testing . J. Am. Pharm. Assoc.55 ( 6 ), 587 – 594 ( 2015 ).

- Dunnenberger HM , BiszewskiM , BellGCet al. Implementation of a multidisciplinary pharmacogenomics clinic in a community health system . Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm.73 ( 23 ), 1956 – 1966 ( 2016 ).

- Haga SB , MoaddebJ , MillsR , PatelM , KrausW , Allen LaPointeNM . Incorporation of pharmacogenetic testing into medication therapy management . Pharmacogenomics16 ( 17 ), 1931 – 1941 ( 2015 ).

- O’Donnell PH , WadhwaN , DanaheyKet al. Pharmacogenomics-based point-of-care clinical decision support significantly alters drug prescribing . Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. doi:10.1002/cpt.709 ( 2017 ) ( Epub ahead of print ).

- Peterson JF , FieldJR , ShiYet al. Attitudes of clinicians following large-scale pharmacogenomics implementation . Pharmacogenomics J.16 ( 4 ), 393 – 398 ( 2015 ).

- Abul-Husn NS , OwusuOA , SandersonSC , GottesmanO , ScottSA . Implementation and utilization of genetic testing in personalized medicine . Pharmgenomics. Pers. Med.7 , 227 – 240 ( 2014 ).

- Bernhardt BA , ZayacC , GordonES , WawakL , PyeritzRE , GollustSE . Incorporating direct-to-consumer genomic information into patient care: attitudes and experiences of primary care physicians . Per. Med.9 ( 7 ), 683 – 692 ( 2012 ).

- Goldsmith L , JacksonL , O’ConnorA , SkirtonH . Direct-to-consumer genomic testing from the perspective of the health professional: a systematic review of the literature . J. Community Genet.4 ( 2 ), 169 – 180 ( 2013 ).

- Kaufman DJ , BollingerJM , DvoskinRL , ScottJA . Risky business: risk perception and the use of medical services among customers of DTC personal genetic testing . J. Genet. Couns.21 ( 3 ), 413 – 422 ( 2012 ).

- Darst BF , MadlenskyL , SchorkNJ , TopolEJ , BlossCS . Characteristics of genomic test consumers who spontaneously share results with their health care provider . Health Commun.29 ( 1 ), 105 – 108 ( 2014 ).

- Starks H , TrinidadSB . Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory . Qual. Health Res.17 ( 10 ), 1372 – 1380 ( 2007 ).

- Willis GB . Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool For Improving Questionnaire Design . Sage Publications, Inc. , CA, USA ( 2005 ).

- Altas.ti ( 2012 ). http://atlasti.com .

- Strauss A , CorbinJM . Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures For Developing Grounded Theory . Sage Publications, Inc. , CA, USA ( 1998 ).

- Miles MB , HubermanAM , SaldañaJ . Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook . Sage Publications, Inc. , CA, USA ( 2014 ).

- Lerner B , MarshallN , OishiSet al. The value of genetic testing: beyond clinical utility . Genet. Med.19 ( 7 ), 763 – 771 ( 2017 ).

- Burke W , LabergeAM , PressN . Debating clinical utility . Public Health Genomics13 ( 4 ), 215 – 223 ( 2010 ).

- Dotson WD , BowenMS , KolorK , KhouryMJ . Clinical utility of genetic and genomic services: context matters . Genet. Med.18 ( 7 ), 672 – 674 ( 2016 ).

- Joseph L , CankovicM , CaughronSet al. The spectrum of clinical utilities in molecular pathology testing procedures for inherited conditions and cancer: a report of the Association for Molecular Pathology . J. Mol. Diagn.18 ( 5 ), 605 – 619 ( 2016 ).

- Kapoor R , Tan-KoiWC , TeoYY . Role of pharmacogenetics in public health and clinical health care: a SWOT analysis . Eur. J. Hum. Genet.24 ( 12 ), 1651 – 1657 ( 2016 ).

- Patel HN , UrsanID , ZuegerPM , CavallariLH , PickardAS . Stakeholder views on pharmacogenomic testing . Pharmacotherapy34 ( 2 ), 151 – 165 ( 2014 ).

- Vernez SL , SalariK , OrmondKE , LeeSS . Personal genome testing in medical education: student experiences with genotyping in the classroom . Genome Med.5 ( 3 ), 24 ( 2013 ).

- Salari K , KarczewskiKJ , HudginsL , OrmondKE . Evidence that personal genome testing enhances student learning in a course on genomics and personalized medicine . PLoS ONE8 ( 7 ), e68853 ( 2013 ).

- Frick A , BentonCS , ScolaroKLet al. Transitioning pharmacogenomics into the clinical setting: training future pharmacists . Front. Pharmacol.7 , 241 ( 2016 ).

- Adams SM , AndersonKB , CoonsJCet al. Advancing pharmacogenomics education in the core pharmd curriculum through student personal genomic testing . Am. J. Pharm. Educ.80 ( 1 ), 3 ( 2016 ).

- O’Brien TJ , LeLacheurS , WardC , LeeNH , CallierS , HarralsonAF . Impact of a personal CYP2D6 testing workshop on physician assistant student attitudes toward pharmacogenetics . Pharmacogenomics17 ( 4 ), 341 – 352 ( 2016 ).

- Weitzel KW , CavallariLH , LeskoLJ . Preemptive panel-based pharmacogenetic testing: the time is now . Pharm. Res.34 ( 8 ), 1551 – 1555 ( 2017 ).

- Luzum JA , PakyzRE , ElseyARet al. The pharmacogenomics research network translational pharmacogenetics program: outcomes and metrics of pharmacogenetic implementations across diverse healthcare systems . Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. doi:10.1002/cpt.630 ( 2017 ) ( Epub ahead of print ).

- Dong D , OzdemirS , MongBY , TohSA , BilgerM , FinkelsteinE . Measuring high-risk patients’ preferences for pharmacogenetic testing to reduce severe adverse drug reaction: a discrete choice experiment . Value Health19 ( 6 ), 767 – 775 ( 2016 ).