Abstract

Background/Purpose: This study investigates challenges that students and faculty face to implement assessment for learning; and the activities, capabilities, enablers, and indicators which could impact performance.

Method: The study is a mixed methods research, cross-sectional, exploratory study. The study was organized through two phases of data collection and analysis (QUAL → quan). Based on qualitative focus group discussions (FGD), we first gathered data through field notes. Later, we engaged in analysis using techniques drawn from qualitative data including categorization, theme identification, and connection to existing literature. Based on this analysis, we developed a questionnaire that could provide quantitative measures based on the qualitative FGD. We then administered the questionnaire, and the quantitative data were analyzed to quantitatively test the qualitative findings. Twenty-four faculty and 142 students from the 4th and 5th clinical years participated voluntarily. Their perception of FA and the cultural challenges that hinder its adoption were evaluated through a FGD and a questionnaire.

Results: The mean score of understanding FA concept was equal in faculty and students (p = 0.08). The general challenge that scored highest was the need to balance work and academic load in faculty and the need to balance study load and training and mental anxiety in students. There was no difference between faculty and students in perceiving “learning is teacher-centered” (p = 0.481); and “past learning and assessment experience” (p = 0.322). There was a significant difference between them regarding interaction with opposite gender (p <0.001). Students showed higher value as regards the “gap between learning theories and assessment practice”, “grade as a priority”, and “discrimination by same faculty gender”.

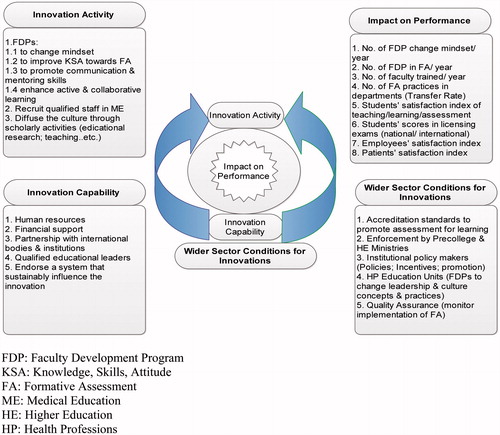

Conclusion: The authors suggested a “Framework of Innovation in Endorsing Assessment for Learning”. It emphasizes a holisitic approach through all levels of the System: Government, Accreditation Bodies, Policy makers; Institution, and Classroom levels.

Introduction

New learning culture had emerged, which strongly emphasizes the important impact of assessment strategies, methods and delivery on learning outcomes (Canadian Council of Ministers of Education Citation2005; Patel et al. Citation2009; Aagard et al. Citation2013). Formative assessment, which enhances student learning through constructive and timely feedback, helps students to evaluate their progress to accomplish their learning objectives; it is referred to by some authors as “assessment for learning”. Both terms are sometimes used interchangeably without providing any explanation of differences (Black et al. Citation2003; Cowie Citation2005; OECD/CERI Citation2010). Gardner (Citation2006) provides some explanation for the existence of two separate terms, saying that formative assessment may be used to refer to on-going in-class assessments that contribute to a final summative assessment that do not “contribute to the students’ learning” and are therefore not considered assessment for learning, in other words the two terms should not be used interchangeably. The definitional issue is beyond the scope of this study, so we are going to use the term “formative assessment” interchangeably with “assessment for learning”. It should be experienced throughout the learning process, to give students the opportunity to use it to promote self-learning, and to provide evidence to inform and shape short-term planning for learning (Burr Citation2009; Brookhart Citation2010; Carless Citation2011). On the other hand, summative assessment – referred to as “assessment of learning” – occurring at the end of the learning process, refers to strategies planned to confirm whether students met the curriculum outcomes. In King Abdulaziz University, summative assessment is mainly the adopted strategy, and the use of summative outcomes for accountability affects ideas and practices in relation to the undergraduate program. Although both formative and summative assessments are conducted, the latter is the one which drives students’ learning and teachers’ instruction. Also, the process by which formative assessment is constructed and implemented does not achieve its desired goal. Pryor and Crossouard (Citation2008) highlighted teachers’ different understandings of formative assessment, equating it either with measurement or as a “process of co-enquiry”. This constituted the need to explore the concept and value of formative assessment among faculty and students.

A systematic literature search of English-language articles on ISI web of knowledge, Google scholar, and Pubmed, was performed by connecting the Mesh terms (“formative assessment”, “assessment for learning”, “challenges”, “culture”, “classroom”). The abstracts of 40 articles were reviewed for the relevance to the topic and were analyzed. Out of these, 17 studies were found relevant to the purpose of the study. All retrieved articles showed extensive discourse about the use of formative assessment in some high-income, developed countries, namely, the UK and the USA. In addition, international support for the transfer of formative assessment policies apparently might support the implementation of formative assessment systems in developing countries whether with constrained resources as in Africa or in the Middle East countries (UNESCO Citation2005; Clarke 2012a). Evidence of actual implementation or use of formative assessment systems in such countries, however, is much less written about. Although many international aid and development agencies as the World Bank and UNESCO, as well as, international and national standards for quality assurance of education, emphasize the potential contribution of formative assessment in raising educational quality (UNESCO Citation2005; Clarke Citation2012a), a further literature search, in January (2014), using the terms “formative assessment” OR “assessment for learning” AND Saudi Arabia, did not yield any results. Although this is not evidence that formative assessment does not exist in Saudi Arabia, it indicates that very little time and research has been dedicated to the formal study of formative assessment usage in Saudi medical schools. The gap found in research on formative assessment for adult learning and growing evidence about the impact of strongly target driven summative systems make it important to examine the political, social, and cultural factors that affect how teachers and students perceive formative assessment in different learning and assessment contexts (Ecclestone Citation2002, Citation2004; Torrance et al. Citation2005). The Center for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) stressed in its report on the need of the consistent use of formative assessment throughout education systems to help stakeholders address the very barriers to its wider practice in classrooms. Almost all countries are congruent in that educational environments; summative tests have high visibility and teachers often feel compelled to “teach to the test”, and students are encouraged to meet performance goals at the expense of learning goals. In several countries, summative assessments have dominated political debate over education. Often, schools with poor results on public examinations face major consequences, such as threatened shut-downs, reconstitution, or firing of teachers. Across countries, new policies have been issued for increasing the transparency, coherence as well as the status of the adult learning sector; however, in some countries, assessments are not well coordinated, and it is not always clear why and how the assessment evaluation information is relevant to the work of teachers, academic leaders, and policy officials. At the same time, investments are still insufficient to meet needs, and it is not clear that even current levels of funding will be sustained over time. These concerns are compounded by a lack of information on how effectively newly endorsed systems are promoting adult learning. Data on outcomes other than certification are rare, and there is little attention to how evaluation data can be used to improve programs and better meet learner needs (OECD/CERI Citation2008). Other challenges that faculty faces on offering formative assessment include the high number of students attending, the time pressure in teaching sessions, the lack of interactivity, students' fear of speaking up, and the limited resources for giving feedback (Krumsvik & Ludvigsen Citation2013). Yorke (Citation2003) showed that at the system level, including learners, faculty, academic leaders, policy officials, and staff members, may have different views of what counts as success and how to measure it. This necessitated strengthening the practice of formative assessment and amending its concept and impact on both teaching and learning among faculty. This is achieved in some countries through providing opportunities for effective training and professional development; however, in most cases, such endeavors were uncoordinated at the various levels of the educational system (Perrenoud 1998). The socio-cultural impact on conceptualizing formative assessment in the Middle East was not explicitly assessed. The purpose of this study is to explore the challenges that hinder the implementation of formative assessment, in general, with particular emphasis on socio-cultural challenges; followed by drawing out implications from the findings for policy-makers concerned with raising standards of the educational outcomes.

This study investigates the following research questions: How is formative assessment perceived by faculty and students? What are the general and cultural challenges that affect the adoption of assessment for learning in the clinical phase of the undergraduate medical curriculum in King Abdulaziz University?

Methods

The study is a mixed methods research, cross-sectional, and exploratory study. A mixed methods research approach is adopted because the use of quantitative and qualitative approaches together can provide a better understanding of the research problem. Both quantitative and qualitative inquiry can support and inform each other. Mixed methodologies can also provide a useful and novel way to communicate meaning and knowledge (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie Citation2004), because they can combine the reliability of counts with the validity of lived experience and perception. This study was organized through two phases of data collection and analysis (QUAL → quan) (Morse Citation2003). Based on qualitative focus group discussions (FGD), we first gathered data through field notes. Later, we engaged in analysis using techniques drawn from qualitative data including categorization, theme identification, and connection to existing literature. Based on this analysis, we developed a questionnaire that could provide quantitative measures based on the qualitative FGD. We then administered the questionnaire, and the quantitative data were analyzed to quantitatively test the qualitative findings (Greene et al. Citation1989; Creswell & Plano Clark Citation2007; Teddlie & Tashakkori Citation2009). Using this sequence of data collection, starting with the FGD followed by the questionnaire, serves the exploratory nature of the study; whereby little is known about the concept of formative assessment and the cultural challenges hindering its appropriate implementation in the Saudi educational community (Dawson et al. Citation1993). Based on the study by Creswell & Plano Clark (Citation2007), the utilized strategy for data mixing was analyzing and presenting each type of data separately and then connect them to answer different aspects of the same or a similar research question. This strategy was adopted to triangulate the results of qualitative analysis in order to validate the qualitative data by using different methods for data collection (FGD then questionnaire) and also by using different sources of data (faculty and students). Mertens (Citation2010) stated that by using multiple sources and methods of data collection, and then cross checking gathered information, the researcher can check for consistency in evidence and establish greater credibility of associated findings. These triangulation methods constituted two out of four of the quality assurance criteria for mixed methods research, namely consistency and neutrality, which correspond to reliability and objectivity in quantitative research, and to dependability and confirmability in qualitative research, respectively (Sale & Brazil Citation2004). FGD were used since it allows exploring of ideas and concepts; provides a window to the participants’ internal thinking; allows probing to obtain in-depth data; and is a useful guide in designing good questionnaires. However, one of the drawbacks of FGD is the difficulty to generalize results, which may not fully represent the opinion of the larger target population; thus, negatively impacting the third criterion of quality assurance of mixed methods research, which is applicability. The latter corresponds to transferability in qualitative research and to external validity in quantitative research. For this reason, we designed a questionnaire by using the qualitative data resulting from the FGD, to compensate for the impaired transferability in the latter; whereby information could be collected from a large portion of a group. In addition, the questionnaire tests how strongly the participants’ beliefs, attitudes, and opinions are held (Dawson et al. Citation1993).

The Good Reporting of a Mixed Methods study (GRAMMS) framework is used for: the design and conduct of mixed methods research; as a mechanism for researchers’ self reflexivity; a framework to ensure a high level of methodological congruence. This is achieved as mentioned before by describing: the justification for using a mixed methods approach to the research question; the design in terms of the purpose, priority, and sequence of methods; each method in terms of sampling, data collection, and analysis; where integration has occurred, how it has occurred and who has participated in it; any limitation of one method associated with the presence of the other method; and any insights gained from mixing methods (O’Cathain et al. Citation2008).

Participants’ population and sample

In King Abdulaziz University, the clinical rotations in the 4th and 5th years were delivered thrice, once for each of three groups of students, each contains about 180 students. The sample size was calculated using a SamplePlanner2007.xls software derived from Agresti and Coull’s (Citation1998) equation to estimate sample sizes required to achieve a specified margin of error and confidence level for a single sample. The sample of students was estimated to be 123 with a maximum error of measurement (5%) and a confidence interval of 95% (Agresti & Coull 1998). Students were invited to voluntarily participate in the study, and a number of 142 volunteered to participate, with an increased rate than the estimated sample by 15.4%.

The faculty who are involved in teaching in the major four clinical departments (Medicine, Surgery, Obstetric and Gynecology, and Pediatrics) were invited to voluntarily participate in the study. Their total is 30 faculty. The estimated sample was 28 and the volunteered sample was 24 according to Agresti and Coull (1998).

Each of the three focus groups contained six participants; two were held for students in a two-way focus group and one focus group for faculty. Students were selected according to their GPA in the previous year, so that the representation of students with a grade of “Excellent”, “Very good” and “Good” were equally represented in each group. This was done because according to Dawson et al. (Citation1993), in focus groups, participants often agree with responses from alike group members which might lead to bias. The faculty selected for the focus group had more than 10 years’ experience in teaching, because according to Ginsburg (Citation2009), teachers need to demonstrate not only deep content knowledge, but also, conceptual understanding, as well as pedagogical content knowledge, i.e. the teacher not only should master the subject matter but also knows a better understanding of the student learning process. Pedagogical content knowledge positively correlates with an increased experience in teaching; consequently, experienced teachers develop a stronger sense of how students develop their understandings of specific content and how they as teachers will be able to prepare lessons around their understandings as well as respond to common misconceptions (Ginsburg Citation2009).

We chose to work on the clinical years of the curriculum because clinical teachers and students at that stage of the curriculum practice formative assessment unconsciously during clinical interviews. In a clinical interview dialoguing between the teacher and the student takes place. The clinical interview can lead to a great deal of knowledge about student thinking; it is a way to inform the teacher about what they know, how they are getting there, and what areas they are struggling with (Ginsburg Citation2009).

Focus group discussion

Three focus group discussions were conducted; one for faculty and a two-way focus group for students, each group consisted of six participants (Bloor et al. Citation2001). The two-way focus group involved two focus groups – one focus group discusses the object, and the other group observes and discusses the interactions of the members of the first focus group. Each focus group was held in a separate room, with a dueling moderator, whereby the focus group included two moderators who purposely got on opposing sides regarding the item being questioned. This reduced the dominance of one opinion and motivated participants to express diverse viewpoints (Maesinero Citation2012). Each focus group had a recorder who is short-handed in notes-taking. Recording the sessions was not favored by the participants as this ought to shackle their free expression of their viewpoints, particularly, if the latter imply political or religious aspects. A structured list was prepared by the authors to trigger the conversation, to be clear and focused, and to be open-ended (Krueger Citation1994). The list for the faculty groups contained three questions: (1) How do you perceive formative assessment?; (2) How do you perform formative assessment?; and (3) What are the challenges that prevent you from performing formative assessment? The list for the students contained two questions: (1) How do you perceive formative assessment?; and (2) Is formative assessment part of your learning methods? Each focus group was scheduled to take an hour. At the end of each focus group, moderators debriefed all authors, and analyzed the gathered information using a content analysis method.

Content analysis began with a set of hypothetical categories which were derived from the research questions that focus on the challenges which hinder the implementation of formative assessment. Four categories are defined: (1) Political/strategic; (2) Economical/resources; (3) Social/religious; and (4) Technical/development. Then the set of data resulting from the FGDs of the participants were read and any new categories that were found other than the hypothetical ones were identified. For each category there was evidence in the data in the form of participants’ responses to the FGD questions. A grid was plotted where the first column contained the categories and the next column showed the participants’ statements which exemplify the category. Re-reading and identifying new categories and statements were iterated until no new categories were identified. Categories were then validated by giving the identified categories and statements to another researcher in the study; who reviewed the same data set and endorsed each category which was recognized. If a category was not endorsed, it could then be rejected from the grid; this was not encountered in the validation process. Then, the statements were converted to themes to reduce the number of statements demonstrated in the grid and to facilitate relating them to the literature during the interpretation stage. This was followed by data analysis, which identified whether or not any one participant in a data set (faculty or students data sets) displayed each category. This was done on an excel spreadsheet, followed by validation of the data analysis. The final grid of category markings was then used for statistical analysis in the form of the frequency and percentage of participants agreeing to each category. The same grid was used to design the questionnaire which constitutes the second phase of the study in order to test the qualitative results.

Survey questionnaire

Participants were surveyed using a questionnaire that was distributed after the FGD and analysis; it was developed based on the results of the focus group discussions. The questionnaire being based on the reviewed literature emphasized its reliability (Brookhart Citation2010; Carless Citation2011). The questionnaire contained 14 items that measured the following:

Understanding of assessment for learning and its implementation during teaching/learning experiences (Yes; No; Not sure scale).

Challenges to adopt assessment for learning [five-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree)].

Overall rating of the level of understanding of assessment for learning (on a scale of 10).

The collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) – version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Quantitative data were summarized and presented as mean and standard deviation (X ± SD). To compare the participants’ scores, the unpaired t-test was used. Comparison between faculty and students’ perceptions was done in order to reveal the magnitude of the difference or similarity in their perspective towards the possible challenges to implementation of formative assessment. Significance was set at the 95% confidence interval (CI). In case the t-test was significant, the effect size was calculated using Cohen’s equation: d = (X2 − X1)/Saverage, where: X2 is mean of group 2, X1 is mean of group 1, and Saverage is the average of both standard deviations. Cohen’s d of 0 to 0.2 standard deviations indicates small effect, 0.2 to 0.5 medium effect, and >0.5 large effect (Soper Citation2013).

Ordinal data obtained from the participants’ response to the questionnaire were converted to quantitative data represented as satisfaction index (SI). Satisfaction index was calculated using the method described by Guilbert (Citation1987). The calculation included the whole rating scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree), instead of including the strongly agree and agree only. This imparted a more accurate representation of the participants’ perception of their satisfaction from the assessment for learning. From the SI, a score was calculated from the 5-point scale. To compare ordinal data, the Mann–Whitney U-test was performed to measure the z-value.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) in the Faculty of Medicine.

Results

Demographic data of participants

Twenty-four faculty members and 142 students completed the questionnaire (100% response rate) ( and ). All 24-faculty members participated in the survey (11 males and 13 females); 71% from the Medicine department; and 54% had more than 10 years of teaching experience. The students were 142, 65.5% were males and 34.5% were females. Half of the participating students has an Excellent grade (A), 40% has Very Good grade, 7% Good and 3% Fair. Forty-four percent came from the 4th year and 56% from the 5th year.

Table 1. Demographic data of participating faculty.

Table 2. Demographic data of participating students.

Identified categories and themes resulting from the focus group discussions of faculty and students

Faculty and students equally agree that political and strategic challenges play a key role in hindering the implementation and utilization of formative assessment in improving learning and teaching (68% agreement each) (). The human resources and time constraints constitute the most important challenging factors to faculty (100% agreement); they constituted a trivial challenge to students (24% agreement). Both students and faculty perceive that faculty development and training in formative assessment practice represent a hindering challenge to building the interaction between them (88% and 72% agreement, respectively), whereby both senses the inadequate pedagogical content knowledge of the teachers who are unable to know how students learn. Social and religious challenges were the least for faculty (33%) and ranked third for students (43% agreement).

Table 3. Identified categories and themes resulting from the focus group discussions of faculty and students.

Score of understanding assessment for learning (formative assessment) on a 10-point scale compared between students and faculty

There were no difference in the mean score of understanding between faculty and students (6.79 ± 1.78 vs. 6.40 ± 2.04), respectively (); with p value of 0.08. The scores for both faculty and students are close to neutral.

Table 4. Score of understanding assessment for learning (formative assessment) on a 10-point scale compared between students and faculty.

Challenges to adopting assessment for learning practice compared between students and faculty

The need to balance workload and academic responsibilities scored the highest by faculty (4.35), followed by time constraint (4.15), and mental anxiety (3.75) (). For students, the need to balance study load and training and mental anxiety scored the highest (4), and time constraint comes after (3.39).

Table 5. Challenges to adopting assessment for learning practice compared between students and faculty.

There was a statistically significant difference in the other three factors. The time constraint and the need to balance workload and academic responsibilities were statistically higher in faculty, while mental anxiety was higher among students. Time constraint and the need to balance workload with academic responsibilities matched positively with the economical/resources category, the percentage of faculty agreeing to this category was higher than the percentage of students ().

There was no statistically significant difference between faculty and students in perceiving “Learning is teacher-centered” (p = 0.481); and “past learning and assessment experience” (p = 0.322), which could be attributed to similar precollege education system. Test grades were considered a priority by both faculty and students, being significantly higher in students. The three items matched positively with the political/strategic category which showed equal agreement percentage between faculty and students ().

There was a statistically significant difference between faculty and students regarding interaction with opposite gender being higher in faculty than students (p < 0.001). On the other hand, students showed statistically higher value than faculty as regards the “gap between learning theories and assessment practice”, which positively matched with the technical/developmental category (), and as well concerning “discrimination by same faculty gender”, which related positively to social/religious category ().

Discussion

The central challenge for educators and students in the Faculty of Medicine to adopt assessment for learning is partly due to the inadequate knowledge in the concept of assessment for learning and its important role in enhancing learning. The stronger impact was due to cultural values in the Saudi society, which could be categorized under four challenges categories: political/strategic, economical/resources, social/religious, and technical/developmental. These challenges are all interrelated, which necessitate a holistic approach to endorse formative assessment with the aim of improving education quality. This was clearly evident by the equal overall scores reported by both faculty and students regarding understanding the concept of assessment for learning, denoting the same cultural values, and precollege education from which they originated, and which is characterized by being teacher-centered, and where there is a great visibility for summative assessment. This is similar to almost all developing countries and the Middle East and Africa. Lewin (Citation1990) has shown that where pressure to perform well in exams is very high, and due to intense competition for employment opportunities, the quality of education provision can become questionable. Increased pressure to perform well in high-stakes examinations can lead to the backwash effect, and steer the focus of learning towards the memorization of simple facts in order to pass exams (Lewin & Dunne Citation2000). Chisholm and Leyendecker (Citation2008) stated that didactic teaching methods are considered to be common in many education systems in developing countries, despite efforts to move towards learner-centered teaching methods. Teacher-centered methods, also known as transmission teaching, are considered to be less demanding of pupils and responsible for “stifling critical and creative thinking among pupils” (Mtika & Gates Citation2010). The similarity between the mean scores for both faculty and students reveals that both sensed the problem and raises an important issue of the dire need to enhance faculty as well as students development in the field of assessment for learning. It is important that faculty consider well the required complex mix of skills in assessment and pedagogical expertise, as well as the softer skills, such as humor, patience, flexibility, and empathy (Heritage et al. Citation2009). Faculty needs deep content knowledge, conceptual understanding, as well as pedagogical content knowledge. This is important in order to effectively implement formative assessment and utilize its information to inform the subsequent instruction; and as well, inform the planning of learners’ activities, which trigger their motivation, self-esteem, and creativity (Ginsburg Citation2009). It is also important to know that formative assessment itself does not result in specific instructional moves and that a teacher has to use his/her own “‘intermediary inventive mind” to make specific decisions about the course of action he/she will take (Ginsburg Citation2009). In our study, both faculty and students realized that though faculty show mastery in content knowledge, they do not possess pedagogical content knowledge, so they are not capable of collecting as well as using data for formative purposes (Perrenoud 1998). Both faculty and students agreed that faculty development is key to drive the learning wheel. A strong focus on building learners’ higher level skills is also vital if teaching and learning are to move beyond mechanistic approaches, where instructors focus on the technical aspects of assessment (Usher Citation2009; Andrade & Valtcheva Citation2009). Faculty needs to challenge learners, and to ensure that they are genuinely involved in the process of learning and assessment. Instructors also need to identify their own values and goals for teaching and learning, to take “ownership” of new approaches, and to pay attention to the impact they are having on learning. With these challenges in mind, countries will need to continue in current direction of strengthening practice through more rigorous qualification and a wide range of professional development approaches, which should be compulsory for all teaching faculty (OECD/CIRI Citation2008). In King Abdulaziz University and in Saudi Arabia, in general, opportunities for effective training and professional development are available to all faculty, yet such endeavors are uncoordinated, necessitating coordinated support to faculty not only at the individuals, institutional, and national systems, but also through creating networks with peers to share experiences with a large number of peers in a community of practice. To conclude, it is clear that faculty development will be a key for several challenges facing formative assessment implementation. It should start with changing the mindset of faculty and students to the correct concept of leadership skills in order to initiate a collaborative climate-based on trust. This could be achieved through active learning, proper mentoring, diffusing the culture through scholarly activities, and sharing of the vision through group dynamic skills. In addition, faculty promotion system requires reform, which should be linked to education improvement, policy development, and accreditation standards (Haywood et al. Citation2011; Pat Hutchings Citation2011).

The time constraint and the need to balance workload and academic responsibilities were statistically higher among faculty, being obligated by the higher administration to be productive in academic work, research, clinical duties in the teaching hospital, besides their private clinics. At the strategic level, there must be a protected time for the variety of faculty duties. Proper selection criteria for students and increased recruitment of highly qualified faculty, which will improve the faculty student ratio, and will translate to creating protected time for them. On the other hand, mental anxiety was higher among students. There are many factors that could contribute to mental anxiety from the student side, yet skilled faculty member who master communication skills, will still be better equipped to handle students’ anxiety and reduce the stress that will result from involving students in the formative assessment process. The fact that scoring high grade was a priority for the students and the learning culture is still teacher-centered will always need reform and changing mindsets at all levels (Black et al. Citation2004).

Social and religious challenges are part of the chain that shackles implementation of formative assessment. Results showed a statistically significant difference between faculty and students regarding interaction with opposite gender being higher in faculty than students. This could be attributed to the social culture of avoiding opposite gender interaction, being more embedded in the faculty than in the newer generation. The latter is more open in accepting opposite gender interaction, due to globalization, through newly adopted externship programs during undergraduate and postgraduate studies. Students expressed their concern about discrimination from same faculty gender, which is not sensed by faculty. This might be due to an inappropriate communication between faculty and students and absence of policies, which define the relation between the student and the teacher apart from gender. This necessitates that the institution develop its own set of policies that define the relation between the teacher and the student. It could be partly due to the big distance between students and faculty in the hierarchy of power, which makes students fear to debate with their teachers and most teachers, particularly seniors, do not accept this.

Students showed statistically higher values than faculty, regarding the gap between learning theories and assessment practice. This might be due to absence of a system to monitor the transfer of knowledge and skills from the faculty development programs’ classrooms to real academic teaching practice (Pat Hutchings Citation2011). The institution must, in addition, develop a range of policies to promote broader practice of formative assessment. These include legislations that promote and support the practice of formative assessment and establish it as a priority. Guidelines on effective teaching and formative assessment should be embedded in the curriculum, and its adoption be monitored by a quality assurance system that reinforces the evaluation culture in the institution. This could be achieved when policies link a range of well-aligned and thoughtfully developed assessments at the classroom, school and system levels. This alignment will provide stakeholders with a better idea as to whether and to what extent they are achieving objectives. Formative assessment, when applied at each level of the system, means that all education stakeholders are using assessment for learning (Black & William Citation1998).

Limitation of the study

The GRAMMS framework is used as a mechanism for the researchers’ self reflexivity; a framework to ensure a high level of methodological congruence. This is achieved by providing the justification for using a mixed methods approach to the research question; the design in terms of the purpose, priority, and sequence of methods; each method in terms of sampling, data collection, and analysis; where integration has occurred, how it has occurred, and who has participated in it; any limitation of one method associated with the presence of the other method; and any insights gained from mixing methods (O’Cathain et al. Citation2008). Triangulation of diverse methods and data collection sources alleviated the limitation of the small sample of faculty, which might affect the generalizability/transferability of results.

Conclusion and recommendations

The authors suggest a “Framework of Innovation in Endorsing Assessment for Learning” (Appendix). It emphasizes that mindsets should be changed at the Macro-level (Government), Meso-level (Institution) and Micro-level (Classroom).

It ensures that classroom, school, and system level evaluations are linked and are used formatively to shape improvements at every level of the system. That is why development of strategies and policies is crucial to promote wider, deeper, and more sustained practice of formative assessment and teaching that is responsive to the needs at all levels. This could be achieved through: initial teacher training and standards for teacher certification; providing teachers already in the workforce the opportunities to participate in professional development programs, test new ideas and methods, and incorporate formative assessment in their regular practice; long-term policies that focus on teaching and learning should be concerned with the process of learning and monitor a range of process and outcome indicators to better understand how well performance is.

There are still significant gaps in understanding the formative assessment. Consequently, more research is needed on effective: formative strategies and teaching; formative approaches for students based on gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status and age. There is a pressing need for research on effective strategies for implementation and scaling-up at all levels. Moreover, there is a need for deeper understanding of the student’s part in the formative process, as for the most effective approaches to teaching the skills of peer- and self-assessment; as well valuing and sensing the importance of formative assessment on their learning and achieving the required competencies.

Q: (QUAL → quan) means that the study is mainly qualitative and triangulated by quantitative method; and that data collection and analysis of qualitative data occur first followed by data collection and analysis of quantitative data.

Practice points

The first step to endorse assessment for learning is changing mindsets at the System, Institution and, Classroom levels.

Development of policies and strategies is important to promote and sustain formative assessment practice that is responsive to the needs and which define the relation between the teacher and student in different cultures.

Institutes have to emphasize faculty development as one of the standards for teacher certification and promotion.

Guidelines on effective teaching and formative assessment should be embedded in the curriculum and its adoption be monitored by a quality assurance system via process and outcome indicators.

Notes on contributors

ROLINA ALWASSIA, MD, FRCPC, FAAP, is an Assistant Professor Radiation Oncology at King Abdulaziz University (KAU) Medical School. She is interested in research on formative assessment and its role in remediation of learning. She is a student in the Master of Medical Education in KAU. She owns the idea of the research; designed the measurement tools; shared in collecting the data; and equally shared in the design and writing of the study.

OMAYMA A.E. HAMED, MD, JMHPE, FAIMER, is a Professor in the Medical Education Department at King Abdulaziz University Medical School, Chairman of the Quality and Academic Accreditation Unit. Her main interests are in assessment, curriculum development, program evaluation, and design and moderation of online MLWeb faculty development courses. She equally shared in the design and writing of the study, particularly the methods and discussion sections; did the analysis of the collected data; and constructed the framework for endorsing formative assessment.

HEIDI AL-WASSIA, MD, FRCPC, is an Assistant Professor in the Pediatrics Department at King Abdulaziz University Medical School. She is interested in educational research. She is a student in the Master of Medical Education in KAU. She shared in designing the measurement tools; and in collecting the data.

REEM ALAFARI, MED, is a Lecturer in the Medical Education Department at King Abdulaziz University Medical School. She is interested in educational research on clinical assessment. She shared in designing the measurement tools; and in collecting the data.

REDA JAMJOOM, MD, FRCSC, MED, is an Assistant Professor in Surgery Department at King Abdulaziz University Medical School. He is the Head of Medical Education Department and is interested in educational research. He shared in collecting the data.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the faculty members and the students in the Faculty of Medicine for their collaboration. Much gratitude goes to the higher administration in the Faculty of Medicine for their sustained support aiming at escalating improvement.

The publication of this supplement has been made possible with the generous financial support of the Dr Hamza Alkholi Chair for Developing Medical Education in KSA.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Aagaard E, Kane GC, Confori L, Hood S, Caverzagie KJ, Smith C, Chick DA, Holmboe ES, Lobst WF. 2013. Early feedback on the use of the internal medicine reporting milestones in assessment of resident performance. J Grad Med Educ 5(3):433–438

- Agresti A, Coull BA. 1998. Approximate is Better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am Stat 52:119–126

- Andrade H, Valtcheva A. 2009. Promoting learning and achievement through self-assessment. Theory Pract 48(1):12–19

- Black P, Harrison C, Lee C, Marshall B, Wiliam D. 2003. Assessment for learning: Putting it into practice. Maidenhead: Open University Press

- Black P, Harrison C, Lee C, Marshall B, Wiliam D. 2004. Working inside the black box: Assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan 86(1):8–21

- Black P, Wiliam D. 1998. Assessment and classroom learning, assessment in education: Principles, policy and practice. Oxfordshire: CARFAX. ISSN: 0969–594X

- Bloor M, Frankland J, Thomas M, Robson K. 2001. Focus groups in social research. London: SAGE Publications

- Brookhart SM. 2010. Formative assessment strategies for every classroom: An ASCD action tool. 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

- Burr S. 2009. Integrating assessment innovations in medical education. Brit J Hosp Med 70(3):162–163

- Canadian Council of Ministers of Education. 2005. Enhancing learning through formative assessment case studies from Canadian and OECD research. Toronto, ON: Canadian Council of Ministers of Education

- Carless D. 2011. From testing to productive student learning: Implementing formative assessment in Confucian-heritage settings. Routledge research in education. New York: Routledge

- Chisholm L, Leyendecker R. 2008. Curriculum reform in post-1990s sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Educ Devel 28:195–205

- Clarke M. 2012b. Measuring learning: How effective student assessment systems can help achieve learning for all [Online]. [Accessed May 2014] Available from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2012/02/15940684/measuring-learning-effective-student-assessment-systems-can-help-achieve-learning-all

- Clarke M. 2012a. What matters most for student assessment systems: A framework paper, the World Bank [online]. [Accessed May 2014] Available from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2012/04/16238771/matters-most-student-assessment-systems-framework-paper

- Cowie B. 2005. Pupil commentary on assessment for learning. Curriculum J 16(2):137–151

- Creswell J, Plano Clark V. 2007. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. London: Sage

- Dawson S, Manderson L, Tallo VL. 1993. A manual for the use of focus groups. Boston, MA: International Nutrition Foundation for Developing Countries (INFDC)

- Ecclestone K. 2002. Learning autonomy in post-compulsory education: The politics and practice of formative assessment. London: RoutledgeFalmer

- Ecclestone K. 2004. Learning in a comfort zone: Cultural and social capital in outcomebased assessment regimes. Assess Educ 11:30–47

- Gardner J. 2006. Assessment and learning. London: Sage

- Ginsburg HP. 2009. The challenge of formative assessment in mathematics education: Children’s minds, teachers’ minds. Human Devel 52(2):109–128

- Greene JC, Caracelli VJ, Graham W F. 1989. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation design. Educ Eval Policy Anal 11(3):255–274

- Guilbert JJ, editor. 1987. How to organize an educational workshop. In: Educational handbook for health personnel. 6th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization

- Haywood AM, Shaw MD, Nelson Laird TF, Cole ER. 2011. Relationship between faculty perceptions of institutional participation in assessment and faculty practices of assessment-related activities. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA

- Heritage M, Kim J, Vendlinski T, Herman J. 2009. From evidence to action: A seamless process in formative assessment? Educ Measure Issues Pract 28(3):24–31

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie A. 2004. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res 33(7):14–26

- Krueger RA. 1994. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications

- Krumsvik RJ, Ludvigsen K. 2013. Theoretical and methodological issues of formative e-assessment inn plenary lectures. Int J Pedagogies Learn 8(2):78–92

- Lewin K. 1990. International perspectives on the development of science education: Food for thought. Stud Sci Educ 18:1–23

- Lewin K, Dunne M. 2000. Policy and practice in assessment in Anglophone Africa: Does globalization explain convergence? Assess Educ 7(3):379–399

- Maesinero S. 2012. Focus group – Pros and cons. [Accessed 9 October 2014] Available from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/focus-groups

- Mertens DM. 2010. Research and evaluation in education in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc

- Morse JM. 2003. Principles of mixed methods and multi-method research design. In Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. pp. 189–208

- Mtika P, Gates P. 2010. Developing learner-centred education among secondary teachers in Malawi: The dilemma of appropriation and application. Int J Educ Devel 30(4):396–404

- O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. 2008. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy 13(2):92–98

- OECD/CERI. 2008. Assessment for learning –formative assessment [Online]. [Accessed May 2014] Available from www.oecd.org/dataoecd/19/31/40600533.pdf

- OECD/CERI. 2010. Assessment for learning – the case for formative assessment’ [Online]. [Accessed 18 May 2014]. Available from www.oecd.org/dataoecd/19/31/40600533.pdf

- Patel VL, Yoskowitz NA, Arocha JF. 2009. Towards effective evaluation and reform in medical education: A cognitive and learning sciences perspective. Adv Health Sci Educ 14(5):791–812

- Pat Hutchings. 2011. From departmental to disciplinary assessment: Deepening faculty engagement. Change: Magazine Higher Learning 43(5):36–43

- Perrenoud P. 1998. From formative evaluation to a controlled regulation of learning processes. Towards a wider conceptual field. In: Assessment in education: Principles, policy and practice. Vol. 5, No. 1. Oxfordshire: CARFAX. 85–102

- Pryor J, Crossouard B. 2008. A socio-cultural theorisation of formative assessment. Oxford Rev Educ 34(1):1–20

- Sale J, Brazil KA. 2004. A strategy to identify critical appraisal criteria for primary mixed-method studies. Quality Quantity 38(4):351–365

- Soper DS. 2013. Effect size (Cohen’s d) calculator for a Student t-test [Software]. [Accessed 6 February 2014] Available from http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc

- Teddlie CB, Tashakkori A. 2009. Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

- Torrance H, Colley H, Garratt D, Jarvis J, Piper H, Ecclestone K, James D. 2005. The impact of different modes of assessment on achievement and progress in the learning and skills sector. Learning and Skills Development Agency. Available from https://www.lsda.org.uk/cims/order.aspx?code=052284&src=XOWEB

- Usher E. 2009. Sources of middle school students’ self-efficacy in mathematics: A qualitative investigation. Am Educ Res J 46(1):275–314

- UNESCO. 2005. Education for all – The quality imperative [online]. [Accessed April 2014] Available from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001373/137333e.pdf

- Yorke M. 2003. Formative assessment in higher education: Moves towards theory and the enhancement of pedagogic practice. Higher Educ 45(4):477–450