Abstract

Background: The psychological construct of emotional intelligence (EI), its theoretical models, measurement instruments and applications have been the subject of several research studies in health professions education.

Aim: The objective of the current study was to investigate the factorial validity and reliability of a bilingual version of the Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Scale (SSREIS) in an undergraduate Arab medical student population.

Methods: The study was conducted during April-May 2012. A cross-sectional survey design was employed. A sample (n = 467) was obtained from undergraduate medical students belonging to the male and female medical college of King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 and AMOS 4.0 statistical software to determine the factor structure. Reliability was determined using Cronbach’s alpha statistics.

Results: The results obtained using an undergraduate Arab medical student sample supported a multidimensional; three factor structure of the SSREIS. The three factors are Optimism, Awareness-of-Emotions and Use-of-Emotions. The reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for the three subscales was 0.76, 0.72 and 0.55, respectively.

Conclusion: Emotional intelligence is a multifactorial construct (three factors). The bilingual version of the SSREIS is a valid and reliable measure of trait emotional intelligence in an undergraduate Arab medical student population.

Introduction

Emotional intelligence (EI) is a psychological construct, which has recently been generating a lot of interest among academics and researchers from health professions (Cherry et al. Citation2012; Abe et al. Citation2013; Doherty et al. Citation2013; Stoller et al. Citation2013) due to its proposed linkages with self-regulation and meta-cognition (Zeidner et al. Citation2004), performance in academics (Brackett & Mayer Citation2003; Naeem Citation2014), success in workplace (Ashkanasy & Daus Citation2005), building relationships, adaptive and coping abilities and wellbeing (Ruiz-Aranda et al. Citation2013).

Salovey and Mayer (Citation1990) first used the term EI, defined as:

Emotional intelligence involves the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions. (p. 189)

Theorists have proposed three models of EI, the ability model, mixed model (Mayer et al. Citation2000) and trait model (Mayer et al. Citation2008), and researchers have developed several instruments to measure EI based on these three theoretical conceptualizations.

The Trait model (Petrides & Furnham Citation1998) envisages EI as “a constellation of emotional self-perceptions located at the lower levels of personality”. Trait EI refers to an individual's self-perceptions of their emotional abilities. This definition of EI encompasses dispositional behavioral tendencies and self-perceived abilities and is measured by self-report instruments (Saklofske et al. Citation2003). Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Scale (SSREI) is an established measure of Trait EI. The SSREI Scale is based on Salovey and Mayer (Citation1990) conceptualization of EI and is widely used in research due to good reliability with Cronbach’s α = 0.87 (Schutte et al. Citation1998), brevity, ease of scoring and availability in the public domain. The SSREI is a 33-item scale assessing EI using a five-point Likert type response format. Developers of the Scale (Schutte et al. Citation1998) recommended using a total score to reflect a single factor or composite EI score, which has been supported in some other studies (Brackett & Mayer Citation2003). However, previous researches have failed to establish a clear factor structure for the scale. Researchers have proposed one (Kim et al. Citation2010), three (Austin et al. Citation2004; Kun et al. Citation2010), four (Petrides & Furnham Citation2000; Chan Citation2004; Fukuda et al. Citation2011) and six factor (Jonker & Vosloo Citation2008) solutions for the SSREI Scale in various populations and cultural groups.

Cross-cultural studies are needed to establish EI as a generalizable, universal construct. In cross-cultural research, a measurement developed in one culture is studied in another. This process involves not only translation of the items of a scale but also examination by researchers that the instrument is applicable and meaningful in another culture (validity). This process includes culturally sensitive adaptation of the instrument and the demonstration of the same “factor structure” across cultures (Matsumoto & Juang Citation2004). It is suggested in theory and research that there are culture-specific generalizables and differences in the way people express, experience and interpret emotions (Scherer & Wallbott Citation1994). Parker and colleagues (Citation2005) have reported that culture can influence the experience and expression of emotions. Cultural differences have to be considered in interpretation of EI as what may be emotionally intelligent in one cultural context may not be in another one (Brackett & Geher Citation2006; Wong et al. Citation2007). Sibia et al. (Citation2003) also report that EI differs across cultures. Carr (Citation2009) found that Asian students demonstrated higher EI on total and subscale scores as compared to White students. Matsumoto (Citation1993) used American born undergraduates of Hispanic, Asian, Caucasian and African descent to identify and evaluate various emotional stimuli and found significant differences among the four ethnic groups.

The psychometric properties of SSREI Scale have been established in samples from the Western (Schutte et al. Citation1998, Citation2009; Petrides & Furnham Citation2000; Austin et al. Citation2004), Chinese (Chan Citation2004) and Japanese (Fukuda et al. Citation2011) populations. However, the applicability of this measure in an Arab population has not been examined. Investigating the psychometric properties in this sample, therefore, would add to the generalizability of existing research findings.

The objective of the current study is to provide evidence of validity, reliability and factor structure of the bilingual English-Arabic version of the SSREI Scale in an undergraduate Arab medical student population.

Methods

Design, sample, procedure and instrument development

The study was conducted during April to May 2012. A cross-sectional survey design was employed. A sample (n = 467) was obtained from undergraduate medical students belonging to the male and female medical colleges of King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The age of students ranged between 17 and 28 years, 71.5% of the sample was males, all students were ethnic Arabs.

A bilingual English-Arabic version of SSREI Scale was developed by translation, back translation and pilot testing. The full details about the development of the scale are reported elsewhere (Naeem et al. Citation2014). The survey instrument was administered to all students who agreed to participate in the study. Informed, written consent was obtained from the participants.

Data analysis

SPSS v 16.0 and AMOS v 4.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) were used for analyses. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA), item analysis and reliability analysis was performed using principal components analysis and varimax rotation. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied to test the fit of the model to the data and to obtain the final scales.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Institutional Review Board of College of Medicine of the King Saud University.

Result

A total of 467 students completed the questionnaire.

Validation of the questionnaire and construction of scales

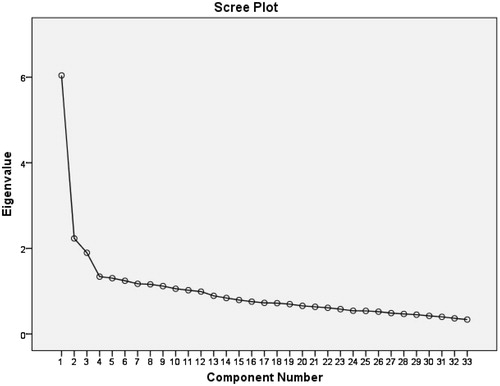

An inspection of the scree plot () indicated that the number of factors best fitting the data was most likely to be three. Therefore, the number of extracted factors in the EFA was set to three.

Initial EFA for 33 items with Eigenvalues indicated a three-factor structure which explained 31% of variance ().

Table 1. Eigenvalue and total variance.

Subsequent EFA’s were performed with removal of items that did not comply with the factor structure. After removal of eight items with highest loading less than 0.4 (items q4, q6, q19, q24, q27, q28, q31 and q33), repeated EFA, and subsequent removal of items with ambiguous loadings (difference of less than 0.1 between the two highest loadings: items q30), reliability analyses were carried out for the resulting three scales (clusters of items). Only one item (q5) was found to contribute negatively to the reliability of the corresponding scale, and therefore was removed. The result of the final EFA is presented in .

Table 2. Final exploratory factor analysis for 24 items.

The loadings indicate subsets of items corresponding to the three subscales. The reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) of these subscales were 0.80, 0.70 and 0.58, respectively. Content analysis of the subsets of items showed that these were consistent with and indicated the characteristics of Optimism, Awareness-of-emotions and Use-of-emotions, respectively.

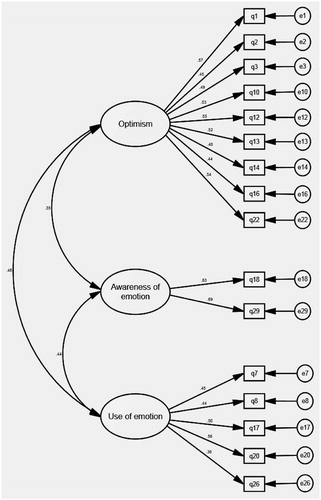

In subsequent confirmatory factor analyses (CFA), the final scales were developed by iteratively removing items with a high modification index in order to obtain a satisfactory fit of the model (items q9, q11, q15, q21 and q23 were removed). For the obtained scales, reliability analysis showed that items q25 and q32 contributed negatively to the reliability and therefore these items were removed. The final scales are shown below in squares ().

Figure 2. Three-factor solution of the Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Scale based on CFA (new 16-item scale).

presents the fit indices corresponding to the final measurement model in ; all fit indices were found to obey the criterion, indicating that the final three-factor model showed a satisfactory fit.

Table 3. Fit indices of the CFA of the proposed three-factor model.

Reliability analysis of subscales

Reliability analysis of the three subscales showed that all items positively contributed to the reliability of the corresponding scale. The number of items and reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) of the three sub scales are shown below ().

Table 4. Number of items and reliability of the three subscales.

Discussion

The current study is the first to investigate the psychometric properties of a bilingual English-Arabic version of SSREI in an undergraduate Arab medical student population.

The current study supports a three-factor model with 16 items. The results of this study contradict the initial uni-factorial model presented by the developers of the inventory (Schutte et al. Citation1998), it also does not conform to the four (Petrides & Furham Citation2000) and six (Jonker & Vosloo Citation2008) factor models. It is similar to the three-factor model of Austin et al. (Citation2004), which included optimism/positivity, regulating/using emotions and appraisal of emotions and contained 24 items of the original 33 items, and Kun et al. (Citation2010) which included appraisal of emotions, optimism and regulation of emotions, intrapersonal and interpersonal utilization of emotions. However, it is different from these models in terms of the number of items, which is 16 and factor loadings that ranged from 0.36 to 0.83 on each of the three factors. Very little commonality was observed with regard to the items removed in the current study and those removed in previous studies reporting a three-factor structure (Austin et al. Citation2004; Kun et al. Citation2010).

The initial reliabilities of the scales were Optimism = 0.80, Awareness of Emotions = 0.70 and Use of emotions = 0.58. However, after CFA, removal of two items which contributed negatively to reliability and further refining of the scales, reliability estimates of the final subscales were 0.76, 0.72 and 0.55, respectively. This compares favorably with the reliability reported by Carrochi et al. (Citation2001, Citation2002); where subscales were reported in the range of 0.80 to 0.55 with lowest being for utilization of emotion subscale, similar to the finding in the current study. However, according to DeVellis’ (Citation1991) recommendation, reliability estimates between 0.65 and 0.70 are minimally acceptable; therefore, the reliability for Use-of-emotions subscale was less than desired and may be improved by adding items.

Limitations

Although confirmatory factor analysis and a satisfactory fit index indicate construct validity of this scale, it must be mentioned that the SSREIS only measures the perceptions of a person regarding his or her own EI and does not fully cover the multidimensional nature of the EI construct. Also SSREIS is a self-report measure and prone to several biases, such as social approval and self-knowledge, etc. Another limitation of the current study is that it examined only the factorial validity and internal consistency (reliability) but did not examine the other forms of validity (predictive) and reliability (test-retest). However, the results reported in this study are based on data obtained from a homogenous group of 467 Arab students, which strengthens the findings of the study.

Conclusions

Based on the findings in the current study, EI is a multifactorial construct (three factors). It is suggested that when using this scale, separate subscale scores of EI rather than a single global score should be reported in line with the nature of the theoretical construct for more useful interpretation.

The bilingual English-Arabic version of the SSREI Scale is a valid and reliable measure of Trait EI, which can be used by researchers and educators to measure and develop EI. It can also be used by students themselves to reflect on their emotional functioning with a view to identifying their strengths and weaknesses and increasing their emotional awareness and adaptability to effectively handle emotionally charged situations during day to day interactions with patients, peers and other healthcare professionals. Students can use this knowledge to improve their interpersonal skills, communication and performance in educational activities involving group work and teamwork.

Notes on contributors

NAGHMA NAEEM, MBBS, PhD, is an Associate Professor and Head of Department, Medical Education, Batterjee Medical College, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. She was previously affiliated with King Saud University Chair for Medical Education Research and Development, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

ARNO MUIJTJENS, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the School of Health Professions Education, Department for Educational Development & Research, Maastricht University.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Prof. Cees van der Vleuten for his help in reviewing the manuscript. We also wish to thank all students who participated in this study.

The publication of this supplement has been made possible with the generous financial support of the Dr Hamza Alkholi Chair for Developing Medical Education in KSA.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Abe K, Evans P, Austin EJ, Suzuki Y, Fujisaki K, Niwa M, Aomatsu M. 2013. Expressing one’s feelings and listening to others increases emotional intelligence: A pilot study of Asian medical students. BMC Med Educ 13:82

- Ashkanasy NM, Daus CS. 2005. Rumors of the death of emotional intelligence in organizational behavior are vastly exaggerated. J Organ Behav 26:441–452

- Austin EJ, Saklofske DH, Huang SHS, McKenney D. 2004. Measurement of trait emotional intelligence: Testing and cross-validating a modified version of Schutte et al.’s (1998) measure. Pers Individ Dif 36(3):555–562

- Brackett MA, Geher G. 2006. Measuring emotional intelligence: Paradigmatic shifts and common ground. In: Ciarrochi J, Forgas JP, Mayer JD, editors. Emotional intelligence and everyday life. New York, USA: Psychology Press. pp 27–50

- Brackett MA, Mayer JD. 2003. Convergent, discriminant, and incremental validity of competing measures of emotional intelligence. Pers Social Psychol Bull 29:1147–1158

- Carr SE. 2009. Emotional intelligence in medical students: Does it correlate with selection measures? Med Educ 43:1069–1077

- Chan DW. 2004. Perceived emotional intelligence and self-efficacy among Chinese secondary school teachers in Hong Kong. Pers Individ Dif 36(8):1781–1795

- Cherry MG, Fletcher I, O’Sullivan H, Shaw N. 2012. What impact do structured educational sessions to increase emotional intelligence have on medical students? BEME Guide 17 Med Teach 34:11–19

- Ciarrochi J, Chan AYC, Bajgar J. 2001. Measuring emotional intelligence in adolescents. Pers Individ Dif 31:1105–1119

- Ciarrochi J, Deane FP, Anderson S. 2002. Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health. Pers Individ Dif 32:197–209

- DeVellis RF. 1991. Scale development: Theory and applications. Applied Social Research Methods Series. Newbury Park, CA: Sage

- Doherty EM, Cronin PA, Offiah G. 2013. Emotional intelligence assessment in a graduate entry medical school curriculum. BMC Med Educ 13:38

- Fukuda E, Saklofske DH, Tamaoka K, Fung TS, Miyaoka Y, Kiyama S. 2011. Factor structure of Japanese versions of two emotional intelligence scales. Int J Testing 11:71–92

- Jonker CS, Vosloo C. 2008. The psychometric properties of the Schutte emotional intelligence scale. SA J Industr Psychol 34:21–30

- Kim DH, Wang C, Ng KM. 2010. A RASCH rating scale modeling of the Schutte Self-Report Emotional Intelligence scale in a sample of international students. Assessment 17(4):484–496

- Kun B, Balazs H, Kapitany M, Urban R, Demetrovics Z. 2010. Confirmation of the three-factor model of the Assessing Emotions Scale (AES): Verification of the theoretical starting point. Behav Res Meth 42(2):596–606

- Matsumoto D. 1993. Ethnic differences in affect intensity, emotion judgments, display rule attitudes, and self-reported emotional expression in an American sample. Motiv Emotion 17:107–123

- Matsumoto D, Juang L. 2004. Culture and psychology. 3rd ed. Bellmont, CA: Wadsworth

- Mayer JD, Caruso DR, Salovey P. 2000. Selecting a measure of emotional intelligence: The case for ability scales. In: Bar-On R, Parker JDA, editors. The handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. pp 320–342

- Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR. 2008. Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits? Am Psychologist 63:503–517

- Naeem N, Van der Vleuten C, Muijtjens AM, Violato C, Ali SM, Al-Faris EA, Hoogenboom R, Naeem N. 2014. Correlates of emotional intelligence: Results from a multi-institutional study among undergraduate medical students. Med Teach 36(S1):S30–S35

- Parker JDA, Saklofske DH, Shaughnessy P, Huang SHS, Wood LM, Eastabrook JM. 2005. Generalizability of the emotional intelligence construct: A cross-cultural study of North American aboriginal youth. Pers Dif 39:215–227

- Petrides KV, Furnham A. 1998. Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. Eur J Personal 15:425–448

- Petrides KV, Furnham A. 2000. On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Dif 29(2):313–320

- Ruiz-Aranda D, Extremera N, Pineda-Galán C. 2013. Emotional intelligence, life satisfaction and subjective happiness in female student health professionals: The mediating effect of perceived stress. Psychiatr Nurs Ment Health 21(2):106–113

- Saklofske DH, Austin EJ, Minski PS. 2003. Factor structure and validity of emotional intelligence measure. Pers Individ Dif 34(4):707–721

- Salovey P, Mayer JD. 1990. Emotional intelligence. Imagin Cogn Pers 9:185–211

- Scherer KR, Wallbott HG. 1994. Evidence for universality and cultural variation of differential emotion response patterning. J Pers Social Psychol 66:310–328

- Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Bhullar N. 2009. The assessing emotions scale. In: Stough C, Saklofske DH, Parker JDA, editors. Assessing emotional intelligence: Theory, research, and application. New York, NY: Soringer. pp 119–134

- Schutte NS, Malouff JM, Hall LE, Haggerty DJ, Cooper JT, Golden C, Dornheim L. 1998. Development and validation of a measure of emotional intelligence. Pers Individ Dif 25(2):167–177

- Sibia A, Srivastava AK, Misra G. 2003. Emotional intelligence: Western and Indian perspectives. J Indian Psychol Abst Rev 10:3–42

- Stoller JK, Taylor CH, Farver CF. 2013. Emotional intelligence competencies provide a developmental curriculum for medical training. Med Teach 35(3):243–247

- Wong CS, Wong PM, Law KS. 2007. Evidence on the practical utility of Wong's emotional intelligence scale in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Asia Pacific J Manag 24:43–60

- Zeidner M, Matthews G, Roberts RD. 2004. Emotional intelligence in the workplace: A critical review. Appl Psychol 53(3):371–399