Abstract

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) caused by novel Corona virus hit Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and resulted in hundreds of mortality and morbidity, fears and psychosocial stress among population, economic loss and major political change at Ministry of Health (MoH). Although MERS discovered two years ago, confusion still exists about its origin, nature, and consequences. In 2003, similar virus (SARS) hit Canada and resulted in a reform of Canada's public health system and creation of a Canadian Agency for Public Health, similar to the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC). The idea of Saudi CDC is attractive and even “sexy” but it is not the best option. Experience and literature indicate that the best option for KSA is to revitalize national public health systems on the basis of comprehensive, continuing, and integrated primary health care (PHC) and public health (PH). This article proposes three initial, but essential, steps for such revitalization to take place: political will and support, integration of PHC and PH, and on-job professional programs for the workforce. In addition, current academic and training programs for PHC and PH should be revisited in the light of national vision and strategy that aim for high quality products that protect and promote healthy nation. Scientific associations, medical education research chair, and relevant academic bodies should be involved in the revitalization to ensure quality of process and outcomes.

Introduction

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) caused by novel Corona virus hit Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and resulted in hundreds of mortality and morbidity, fears and psychosocial stresses among population, economic loss and major political change at the Ministry of Health (MoH). Until 4 June 2014, 688 confirmed infections and 282 deaths from MERS. Although the virus was discovered two years ago, confusion still exists about its origin, nature, and consequences. Health authorities admitted that there are “major gaps in knowledge about the epidemiology, community prevalence, and clinical range of MERS-CoV” (Assiri et al. Citation2013). But public may see it as a failure of health system and public health preventive measures reflected in articles and comments in the mass and social media (Abid khazandar Citation2014).

It is understandable in the beginning that emerging viruses are unclear and unpredictable in terms of sources, route of transmission, and behavior (Skelding & Upshur Citation2010). Sound public health system should take in consideration such circumstances and be prepared to manage the situation without disrupting services or alarming public unnecessarily. Our public health system developed over the last 90 years, well supported by the government, and approved primary health care (PHC) to achieve “Health for All” since Alma-Ata Declaration more than 35 years ago. However, MERS indicates an urgent need to revitalize national public health system starting with revitalization of PHC and public health (PH) in order to deal cost-effectively with outbreaks, communicable and non-communicable diseases, and other health challenges of the twenty-first century (Khaliq Citation2012).

This article proposes three initial, but essential, steps for revitalization to take place at Ministry of Health (MoH) as the major provider of public health and the ultimate responsible body for all health systems and services in KSA (public and private). The proposal stems from experience and literature on PHC and PH as the cornerstone of any cost-effective healthcare system that prevents diseases, promotes health, engages community, and coordinates with relevant health organizations to prevent and manage health hazards and diseases (The Lancet Citation2008; Walley et al. Citation2008; Bhatia & Rifkin Citation2010). The article starts with a brief description of the development of public health system and relevant higher education programs. The aim is to share one important lesson learned from MERS that can transform current public health system to a more cost-effective system that deal appropriately with MERS and other health challenges.

Development of public health systems in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

In 1925, the first health department in KSA was established to manage and supervise few dispensaries, health posts, and hospitals serving citizens as well as pilgrims coming to Makkah (Almalki et al. Citation2011). Later became General Directorate of Health and Aid. In 1950, MoH was established reflecting the rapid developments and growth in health services. Until late 1970s, the health system was oriented more to curative care and drug prescriptions with only few vertical preventive programs related to tuberculosis, malaria, and bilharzia (Almalki et al. Citation2011). In 1978, KSA was among the first members of the World Health Organization (WHO) who signed Alma-Ata Declaration to adopt PHC approach to achieve “Health for All”. Since then tremendous growth in health care facilities, structure, and services occurred but without consistent development of comprehensive, continuing, and integrated PHC and PH.

Currently, there are more than 2037 PHC centers and 244 hospitals under the direct jurisdiction of MoH, which accounts for 60% of public health provision while the other health sectors (government and private) provide the remaining 40% under the supervision of MoH. Other governmental health sectors that provide 20% of services include Military Medical Services under Ministry of Defense, National Guard Health Affairs under Ministry of National Guard; Security Medical Services under Ministry of Interior; University's teaching hospitals and PHC centers; specialized hospitals, such as King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center; medical cities and many others (Almalki et al. Citation2011).

These health sectors resemble more or less MoH in their development: initially oriented to curative and drug prescription than adopted PHC. For example, in 1978, the Military Hospital in Riyadh (capital of KSA) established its first department of PHC and later changed the name to family and community medicine. In 1994, National Guard Health Affairs (NGHA) formed the directorate of PHC that integrated family and community medicine with preventive medicine and all medical services outside the hospitals under one directorate to serve individuals as well as the community of National Guard personnel and their beneficiaries. In 1999, Security Forces Hospital adopted PHC clinics and approach to serve their population. Nowadays, almost all health authorities and medical cities in KSA have departments of PHC, family and community medicine, and/or preventive medicine to provide services and programs related to PHC and PH. Generally, health services are provided through three main levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary care. The main workload is at the primary level but the main support organizationally and financially is at tertiary and secondary care.

In 2009, the minister of health formed a national committee to review PHC and PH at MoH (the author was a member). A comprehensive report was submitted as a result of many meetings, literature review, site visits, and interviews with both high-rank decision makers at MoH and frontline providers. Among the committee's recommendations were the importance of revitalizing PHC and PH organizationally, functionally, and financially, creation of a high-rank leading position for PH, and a higher representation for PHC at MoH. In 2010, a deputy minister position for PH was established to oversee a wide range of directorates/departments and services related to PHC and PH. This could have been a landmark towards more managed and supported structure that will revitalize high quality PHC and PH at MoH and to be a model for other health sectors to follow. Another recent important development related to PH is the formation of Saudi Scientific Association for Public Health (SAPH) to promote professions and professionals of public health in KSA. SAPH believes in public health standards and services that go beyond healthcare provision and in line with the USA National Public Health Performance Standards (Citation2014). These developments and structure can be revitalized to deliver their potentials. However, without well-qualified and properly trained personnel in PHC and PH revitalization may not achieve its objectives. Current academic and training programs related to PHC and PH should be considered in the revitalization process.

PHC- and PH-related academic and training programs

King Saud University (KSU) in Central province formed the first academic department related to public health under the name of preventive medicine almost 40 years ago and now called family and community medicine. In 1983, the department started its first master program in PHC and replaced later by Saudi Board in Family and Community Medicine (SBFCM). More recently, the department started masters programs in public health and health informatics in addition to SBFCM residency programs. The department also provides diploma in field epidemiology in collaboration with MoH. In 1981, King Faisal University (in Eastern Province) started its Fellowship in Family and Community Medicine and later replaced by SBFCM. The same can be said about King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah (Western Province). Currently, all major universities in KSA have departments and programs related to PHC and PH. In fact, five colleges of public health and health informatics were established over the last 10 years to provide postgraduate and graduate degrees in public health and health informatics. Moreover, MoH provides program on “mass gathering medicine” in addition to the field epidemiology program that has been running for more than 20 years in collaboration with KSU.

In 1995, the Saudi Board of Family and Community Medicine (SBFM) was established as the 5th major specialty board under the Saudi Commission for Healthcare Specialty Council (SCHS) to oversee all relevant residency programs provided by universities and training medical centers. Medical graduates enroll in four years structured training program after internship followed by a final examination of the SBFM. Fifteen months of the training period are spent in a training center for family and community medicine (a modern PHC center with specific criteria to be accredited as a training center), while the rest of the program spent in different specialties and sub-specialties in accredited training hospitals. This is in addition to the board of community medicine.

Certainly, the above-mentioned programs have contributed to capacity building of well-educated and trained leaders, researchers, and practitioners in PHC and PH. However, it may be worthwhile to consider common purpose, coherence, and optimizations of these programs in the light of revitalization of PHC and PH to ensure products meet current and future health challenges.

Revitalization of public health system in KSA

In 2003, SARS outbreak in Canada initiated reform of the entire Canada's public health system and resulted in the creation of a Canadian Agency for Public Health, similar to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to coordinate public health activities throughout the country (Expert panel on SARS Citation2003; Public Health Agency of Canada Citation2004, Citation2006). The idea of Saudi CDC to deal with MERS and other outbreaks is attractive and even “sexy” but it is not the best option for KSA. To create another health sector in already multi-sectors health system means more duplication and waste of resources without evidence-based beneficial outcomes to the nation (Wilson Citation2004).

The best approach for KSA is to revitalize current health systems on the basis of comprehensive, continuing, and integrated PHC and PH that provide curative, preventive, and promotion services and programs at all levels. The Canadian experience emphasized the importance of having effective public health services and programs at all levels: “The SARS experience laid bare the pressing need for effective public health programs and services and the necessity for their strengthening locally, provincially and nationally” (Interim Report of the Capacity Review Committee Citation2005, p. 1).

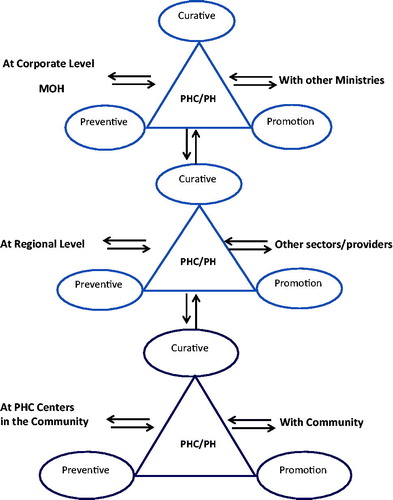

The case for PHC as the corner stone of any effective public health system is strong and based on sound evidences. PHC was declared the model for global health policy since Alm-Ata Declaration and re-emphasized strongly “more than ever before” in its 30th Anniversary (WHO 2008). Almost all literature and experiences on cost-effective health system are linked to proper implementation of comprehensive PHC and PH (Lewin et al. Citation2008; The Lancet Citation2008; Walley et al. Citation2008; Frenk Citation2009; Bhatia & Rifkin Citation2010; Al-Shehri Citation2013, Citation2014). Implementation of comprehensive PHC put Cuba “on a par with those of developed countries that have several times its budget” (Magnussen et al. Citation2004). Public health improvements contributed significantly to eradication of lethal diseases, increase in life expectancy, and effectiveness of health systems. So it is proved beyond doubt scientifically that strong PHC and PH are key factors in better health outcomes. In its health strategic plan, KSA emphasized PHC as the corner stone of all health sectors: “To regard primary health care services provided by the Ministry of Health and other health sectors, including the private sector - the cornerstone of the health system” (Saudi Health Council Citation2012). What needs to be done is to put theory into practice by revitalizing PHC and PH programs and services at all levels from the PHC centers in the community through regional health affairs to corporate offices and departments at MoH. shows the importance of integrating curative, preventive, and rehabilitative services in the community through PHC centers and at all levels (regionally and centrally).

Figure 1. Comprehensive, integrated and continuing PHC and PH Services at community, regional and corporate levels.

In this way public health hazards can be prevented, detected early when occurred, and managed comprehensively for the benefit of the whole system and the nation. “The Alma Ata Declaration promoted Primary Health Care (PHC) as its central means toward good and fair global health - not simply health services at the primary care level (though that was important) but rather a health system model that acted also on the underlying social, economic and political causes of poor health” (Frenk Citation2009). Revitalizing PHC and PH to be integrated, comprehensive and continuing programs and services at all levels () should revitalize the entire health system to look into the six building blocks identified by WHO (Citation2010): service delivery, workforce, information and clinical data, medical and logistical products, finance, leadership and governance.

As a start three main steps need to be taken to initiate revitalization:

Political will and support for PHC and PH: PHC started in the early 1980s with full support and enthusiasm from high authority in MoH and in presence of strong PHC leadership. Over time, such support and enthusiasm fade away and consequently lead to insufficient resources in terms of qualified workforce, budget, stewardship and governance, and community-based programs. MERS and past outbreaks (e.g. Rift valley fever), current epidemic of NCDs, and the high costs of health system that based on tertiary care tell us clearly that PHC and PH have not been well supported to prevent this situation or at least minimize its effects. Challenges mentioned in the latest strategy of the Council of Health Services (Saudi Health Council Citation2012) namely: change of disease patterns, change of cause of death patterns, urbanization, workforce, financing and expenditure, and management and information systems cannot be addressed in absence of sound and well supported PHC and PH. Most of current and future health challenges in KSA need community-based curative, preventive, and health promotion programs more than hospital-based tertiary services. Engagement of community to participate actively in changing their life style and take more control of their health cannot be done without enough and qualified PHC and PH personnel in the ground. Problem of employment of thousands of diploma holder Saudi nurses can be solved by utilizing them in PH campaigns and programs in the community with proper support (Al-Shehri Citation2013); adopting public health informatics can transform public health functions and management of information (Al-Shehri Citation2014). Investing in PHC and PH to lead the national health system enhances its effectiveness, safe money, and improve health outcomes (Lewin et al. Citation2008; The Lancet Citation2008; Walley et al. Citation2008; Frenk Citation2009; Bhatia & Rifkin Citation2010). Building public health system of KSA on tertiary care services and specialized centers of excellence is ineffective, costly, and lack evidence. The case of MERS showed that tertiary hospitals and center of excellence can collapse and even become a source of infection. Proper PHC and PH structure and measures enhance community-based epidemiological surveillance and health promotions to prevent and control diseases in the community before it reaches to tertiary care facilities and become a hospital acquired diseases that resulted in huge loss of health and economy (The Lancet 2014). High authority at MoH should give full political and financial support to PHC and PH to lead national health system in managing cost-effectively current and future health challenges. Support includes high priority to PHC and PH services and programs, appointing and developing well qualified leadership in the field (Al-Shehri & Khoja Citation2012), proper organizational structure that ensure responsibility and accountability, adequate and needs based budget, and on-job professional development programs, and monitoring and evaluating progress on the basis of clear key indicators.

Integration of PHC and PH organizationally and functionally at all levels: All activities and functions of PHC and PH have been put, recently, under the deputy minister for public health. This is a welcome step towards integration that avoids segregations, fragmentations, duplications, and contradictions of rules and activities. However, there are still many vertical programs of PH that are not coordinated or connected with PHC activities and functions. Management of MERS showed segregation and fragmentation between PHC and PH functions where a vertical management took place by a corporate office with little involvement of PHC in case findings, community surveillance, public education, and case management. After two years, MoH and other health-sectors realized the importance of PHC and started to send SMS messages to public asking them to consult their PHC centers if they have the symptoms of MERS! The questions here do these PHC centers and services have the necessary resources and support? Are PHC and PH activities and functions integrated to optimize outcomes and avoid duplications, segregations, and conflicting messages? Luckily, MERS so far is not pandemic but experts maintain that pandemic is coming and it is just a matter of time! So it is important to learn from MERS and integrate all functions and services of PHC and PH into clear and seamless system with full support in terms of enough competent workforce, professional development programs, and budget to ensure proper alert system, cost-effective, and comprehensive response. Setting central command and control office to manage MERS or other communicable disease without competent personnel in the ground working together is putting the “cart before the horse”.

After long segregation and isolation between PHC and PH in the USA, calling for integration has become a hot topic recently (Koo et al. Citation2012). The old fashion pyramid of levels of health services and segregation of services is outdated. Unfortunately, our health system is not only maintaining such old fashioned pyramid but even worse in an inverted position in terms of support and resources for PHC and PH. This has to be corrected to prevent its collapse and transform it to a more integrated health system that responds cost-effectively to population health needs. More than 85% of workload takes place at PHC and PH levels. Integrating curative, preventive, and rehabilitative services of both PHC and PH programs at the health centers in the community, regional health affairs, and at the central corporate level () should create teamwork and multidisciplinary approach to deal cost-effectively with public health issues. Professional development programs to enhance understandings of teamwork, roles and functions that ensure quality of provision should support integration.

Professional development programs: PHC and PH scientific associations, medical education research chair, and other relevant professional bodies may be tasked to design, supervise, and evaluate on-job professional development programs for all PHC and PH workforce (doctors, nurses, allied health, managers, and others). The aim of such programs is to ensure proper revitalization that enhance quality of PHC and PH provision, strengthen teamwork, and multidisciplinary approach to health problems, and measure the impact and progress.

In addition to the above three initial steps, current academic and training programs relevant to PHC and PH (mentioned briefly above) should be revisited in terms of their quality, relevance, duration and outcomes to ensure enough and well qualified products that maintain and develop further high quality PHC and PH. “No attempt to improve public health will succeed that does not recognize the fundamental importance of providing and maintaining … an adequate staff of highly skilled and motivated public health professionals. Our national aim should be to produce a cadre of outstanding public health professionals who are adequately qualified and compensated, and who have clear roles, responsibilities, and career paths” (The National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health Citation2003). Academic and training programs relevant to PHC and PH must be of high quality, recognized, and rewarded from relevant organization (e.g. from SCFHS and Civil Citizen Bureau) in order to attract high caliber candidates. Appropriate recognition and creation of attractive job opportunities for graduates of these programs are essential to enhance interest of high quality candidates to join these programs and meet the great needs on the ground (Sharma & Zodpey Citation2011). For qualified PHC and PH personnel to work in remote health centers and participate in community health-related activities, they need to be rewarded financially and professionally to the level of their counterparts in hospitals if high quality provision of PHC and PH is to be achieved. As The Lancet (Citation2006) said: “restricted investment in public health services and education, have left many countries with critical shortages of health workers … This situation is made worse by changing epidemiological threats and the fact that the skills of available professionals are often not well matched to the local population's health needs”. KSA has invested in PHC and PH over the last 35 years and time has come to revitalize these services and programs for better outcomes.

In conclusion, a very important lesson learned from MERS in KSA is to revitalize our public health system through revitalization of PHC and PH services and programs. Experience and literature support the comprehensive, continuing, and integrated approach of PHC and PH as the most cost-effective approach to prevent disease, promote health, and optimize health system. Political will and support, integration of PHC and PH, and on-job professional development programs are three initial steps towards successful revitalization. In addition, higher educational and training programs for PHC and PH are to be reviewed, recognized, and rewarded properly to ensure sufficient and high quality products that lead the way towards healthier nation and cost-effective health system.

Notes on contributor

Dr. ALI M. AL-SHEHRI, MD, MSc, MPhil, FRCGP, MFPH, ACHE, is Associate Dean, Academic and Students Affairs, College of Public Health and Health Informatics, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Science, President of Saudi Association for Public Health and Consultant Family and Community Medicine, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh.

The publication of this supplement has been made possible with the generous financial support of the Dr Hamza Alkholi Chair for Developing Medical Education in KSA.

Declaration of interest: The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Abid khazandar. 2014. “No wonder if disease spreads”. Arabic column in Riyadh Newspaper, 16 June, issue 16793, p. 22

- Al-Shehri AM, Khoja TA. 2012. Doctors and leadership of healthcare organizations. Saudi Medical J 30(10):1253–1255

- Al-Shehri AM. 2013. A developmental model of nursing in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical J 34(10):1083–1085

- Al-Shehri AM. 2014. Can informatics transform Public health in KSA? J Int Health Inform 8(2). [Accessed July 2014] Available from http//www.jhidc.org/index.php/jhidc/issue/current

- Almalki M, Fitzgerald G, Clark M. 2011. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: An overview. Eastern Mediterranean Health J 17(10):784–793

- Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, Al-Rabiah FA, Al-Haijar S, Al-Barrak A, Flemban H, Al-Nassir WN, Balkhy HH, Al-Hakeem RF, et al. 2013. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of MERS from Saudi Arabia: A descriptive study. Lancet 13(9):752–761

- Bhatia M, Rifkin S. 2010. A renewed focus on primary health care: Revitalize or reframe? BioMedCentral – The Open Access Publisher Globalization and Health 6:13

- Expert panel on SARS. 2003. Expert panel on SARS and Infectious disease control. for the public’s health. [Accessed July 2014] Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/pub/ministry_reports/walker_panel_2003/walker_panel.html

- Frenk J. 2009. Reinventing primary health care: The need for systems integration. Viewpoint 374:170–173

- Interim Report of the Capacity Review Committee. 2005. Revitalizing Ontario's Public Health Capacity: A Discussion of Issues and Options. Queen's Printer for Ontario. Available from www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/capacity_review05.pdf

- Khaliq A. 2012. The Saudi Healthcare System: A view from the Minaret. World Health Popul 13(3):52–64

- Koo D, Felix K, Dankwa-Mullan I, Miller T, Waalen J. 2012. A call for action on primary care and public health integration. Am J Preventive Med 42(6S2):S89–S91

- Lewin S, Lavis JN, Oxman AD, Bastías G, Chopra M, Ciapponi A, Flottorp S, Martí SG, Pantoja T, Rada G, et al. 2008. Supporting the delivery of cost-effective interventions in primary health-care systems in low-income and middle-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Lancet 372:928–939

- Magnussen L, Ehiri J, Jolly P. 2004. Comprehensive versus selective primary healthcare. Health Affairs 23(3):167–176

- National Public Health Performance Standards, CDC. 2014. The public health and the 10 essential public health services. [Accessed July 2014] Available from: www.cdc.gov/nphpsp/essentialservices.html

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). 2004. Enhancing the public health infrastructure: A prescription for renewal. [Accessed July 2014] Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/sars-sras/naylor/4-eng.php

- Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). 2006. Learning from SARS: Renewal of public health in Canada. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/sars-sras/naylor/

- Saudi Health Council. 2012. Health strategy. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Saudi Health Council Press

- Sharma K, Zodpey S. 2011. Public health education in India: Need and demand paradox. Indian J Commun Med 36(3):178–181

- Skelding J, Upshur R. 2010. SARS, pandemics and public health. IAJ 10:41–50

- The Lancet. 2006. The crisis in human resources for health. Lancet 367:1117

- The Lancet. 2008. A renaissance in primary health care. Lancet 372:863

- The Lancet. 2014. Making primary care people-centred: A 21st century blueprint. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61243-5

- The National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health. 2003. Learning from SARS: renewal of Public Health in Canada. Health Canada

- Walley J, Lawn JE, Tinker A, de Francisco A, Chopra M, Rudan I, Bhutta ZA, Black RE, Lancet Alma-Ata Working Group. 2008. Primary health care: Making Alma-Ata a reality. Lancet 372:1001–1007

- Wilson K. 2004. A Canadian Agency for Public Health: Could it work? CMAJ 170(2):222–223

- World Health Organization. 2008. World Health Report: Primary Health Care: now more than ever. Geneva: WHO

- World Health Organization. 2010. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems. The six building blocks contribute to the strengthening of health systems. Available from www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/WHO_MBHSS_2010_full_web.pdf