ABSTRACT

Background: Supporting people with intellectual disability to make decisions is an important issue for policy implementation yet there is little evidence about the practice of providing support.

Method: This study aimed to understand the experiences of family members and disability support workers in providing support to adults with intellectual disability in Victoria, Australia. Twenty-three people drawn from these two groups participated in individual or focus group interviews.

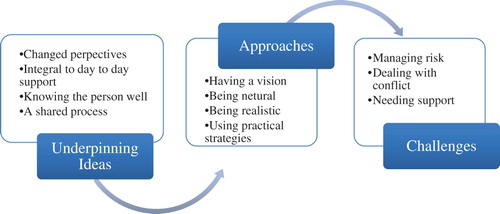

Results: Three major themes emerged from inductive thematic analysis: their ideas about decision support, approaches to support, and challenges they faced. Overall these revolved around juggling rights, practicalities, and risks

Conclusions: This study identified some of the challenges and practical strategies for providing decision support that can be used to inform practice and capacity building resources for supporters.

Background

Exercising choice and making decisions about one’s own life are important both to personal wellbeing and an individual’s sense of identity (Brown & Brown, Citation2009; Nota, Ferrari, Soresi, & Wehmeyer, Citation2007). In the last decade service system reform, such as personalisation in the UK, the USA, and Australia, has generated greater opportunities for people with intellectual disability to participate in decisions about the services they receive and increase choice over all aspects of their lives (Bonyhady, Citation2016; Carney, Citation2013; Sims & Gulyurtlu, Citation2014). In parallel, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (the Convention) (Citation2006) has been the catalyst for significant debate about decision-making rights of people with disabilities. Commentators have interpreted Article 12 of the Convention as breaking the nexus between mental and legal capacity, by asserting that everyone has the right to make decisions about their own life, irrespective of cognitive ability, and to have the necessary support to do so (Bach, Citation2017; Series, Citation2015).

The concept of supported decision making, first developed in Canada in the 1990s, is seen as a means of enacting intentions of the Convention (Bach, Citation2017; Carney, Citation2013; Series, Citation2015; Stainton, Citation2016). The underlying premise of supported decision making is that everyone has the right to self-determination and to exercise legal capacity and can express choices with support provided in the context of trusting relationships. The roles of supporters are to explain issues, explore options, and support the expression of preferences (Carney & Beaupert, Citation2013), and may extend to engaging third parties in decision-making processes, making agreements that give effect to decisions, and implementing decisions (Bach & Kerzner, Citation2010). For people with more severe intellectual disability support may extend to interpreting signs and preferences, ascribing agency to a person’s actions or co- constructing preferences (Series, Citation2015). Supported decision making, understood in this way requires a legal framework that recognises decision making as a shared process and gives formal standing to supporters. This formalised support process is significantly different from either informal recognition of the role of supporters in decision support or appointment of substitute decision makers who may be guided by the person’s preferences as well as their best interests.

Despite significant attention from law reform commissions, there are few supported decision-making schemes currently recognised, other than Representation Agreements in British Columbia, Canada, and the Godman in Sweden (Beadle-Brown, Citation2015; Stainton, Citation2016; Tideman, Citation2016). Some of the reasons for this lack of formal supported decision-making schemes are associated with the perceived vulnerability of people with cognitive impairment to coercion and a lack of empirical evidence about supported decision making and whether in practice it reflects espoused principles (Boundy & Fleischner, Citation2013; Then, Citation2013).

No formally recognised scheme for supported decision making relevant to people with intellectual disability currently exists in Australia. Decision support is provided informally by family, significant others, paid staff or advocates, or formally through the appointment of a guardian. As a result, little monitoring or accountability is placed on informal decision supporters and limited capacity building resources are available for either supporters or those they support. Nevertheless, there are increasing expectations that decision supporters, whether formal or informal, should acknowledge and respect the preference and rights of the individual person with intellectual disability they support. For example, decision-making principles, though not yet formally adopted, have been developed by the Australian Law Reform Commission (Citation2014), some guidance for disability support workers about decision support has been developed by the Department of Human Services (Citation2012), and various short-term pilot schemes have explored increasing the availability of decision support and ways to increase the capacity of supporters (for review see Bigby et al., Citation2017). An underlying premise of the Australian National Disability Insurance Scheme Act (Citation2013) is that people have the right to make their own decisions and an onus is placed on nominees to take account of the person’s preferences and rights. However at the time of writing, it is understood that very few participants have had a nominee appointed, and support with decision making rests primarily on informal support relationships.

As already suggested, there is scant empirical research about the practice of supported decision making in formal schemes. A small body of research has investigated factors that influence opportunities for involvement of people with intellectual disability in decision making and the nature of informal decision-making support. For example, positive attitudes of others towards risk, and creation of opportunities for choice enable increased involvement in decision making (Kjellberg, Citation2002; Mill, Mayes, & McConnell, Citation2010; Timmons, Hall, Bose, Wolfe, & Winsor, Citation2011). The relationship between the supporter and the person being supported has been highlighted as an important factor in the process of providing decision support (Burgen, Citation2010; Kjellberg, Citation2002), as has tailoring of support and communication to the needs and skills of the individual in the context of formal meetings as well as more individualised interactions (Antaki, Finlay, Walton, & Pate, Citation2008; Conder, Mirfin-Veitch, Sanders, & Munford, Citation2011; Espiner & Hartnett, Citation2012; Rossow-Kimball & Goodwin, Citation2009). Specific strategies such as staff practice based on active support have also been found to play a role in shaping participation in choice and decision making (Beadle-Brown, Hutchinson, & Whelton, Citation2012).

Concern has been raised about confusion over the legal standing of informal supporters, and the sometimes paternalistic nature of decision support (Bigby, Bowers, & Webber, Citation2011; Bowey & McGlaughlin, Citation2005; Dunn, Clare, & Holland, Citation2010; Kohn & Blumenthal, Citation2014). Several studies have identified the restrictive impact that staff or family expectations can have on decision-making opportunities (Antaki, Finlay, & Walton, Citation2009; Healy, McGuire, Evans, & Carley, Citation2009; Rossow-Kimball & Goodwin, Citation2009). Ferguson, Jarrett, and Terras (Citation2011) and Pilnick, Clegg, Murphy, and Almack (Citation2010) reported how supporters actively shaped decisions to reduce risk or ensure an outcome they perceived to be in the best interests of the person with intellectual disability. The negative impact of staff with inadequate communication skills, knowledge of the impact of intellectual disability, or awareness of their own values was evident in a number of studies (Antaki et al., Citation2009; Ferguson et al., Citation2011; Sowney & Barr, Citation2007). Such factors were compounded by risk averse organisational management (Hawkins, Redley, & Holland, Citation2011) or the pressured nature of some environments in which decisions have to be made (Bigby et al., Citation2011; Sowney & Barr, Citation2007). In particular, one UK study illustrated the poor outcomes of relying on checklists as a resource for support workers to support decision making when they are inadequately trained in reflective practice and unaware of the influence of their own preferences and values (Dunn et al., Citation2010). Several authors have also highlighted the impact of limited resources on options available to an individual and thus on decision making (Hodges & Luken, Citation2006; Kjellberg, Citation2002).

No studies with people with intellectual disability have completed the type of in depth qualitative investigation exploring the experiences of decision-making supporters conducted by Knox, Douglas, and Bigby (Citation2015, Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2016c) with people with cognitive disability as a result of severe brain injury. This work suggests several key constructs in decision support processes occur across a range of supporters, family members, support workers and friends, and a broad range of decisions. Paramount among these was the importance of a positive support relationship whereby the individual with brain injury was held as central to the decision making and the supporter(s) knew the person well, understood the consequences of the brain injury for the person, appreciated what was important to them, and took a positive approach to risk.

Knowledge about communication, autonomy, and choice making (Cooper & Browder, Citation2001; Fisher, Bailey, & Willner, Citation2012; Wennberg & Kjellberg, Citation2010; Willner, Bailey, Parry, & Dymond, Citation2010) provide important foundations for thinking about the practice of decision support as do theoretical models such as that proposed by Shogren and Wehmeyer (Citation2015). Nevertheless, evidence based on the actual experience of providing support for decision making is essential not only in understanding the process of support but also to developing the practice of support provision that more closely resembles the rights principles of supported decision making and the Convention.

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of family members and workers in disability support services in providing support for decision making to adults with intellectual disability, and to identify some of the tensions or dilemmas that supporters faced in providing support as well as the strategies they used. We anticipated that this knowledge would inform the development of strategies to enhance the capacity of supporters to maximise opportunities for people with intellectual disability to make their own decisions and provide decision support that recognises and respects their rights, will and preferences.

Method

We adopted a social constructionist theoretical perspective which reflected our focus on experiences – the subjective realities of decision supporters of people with intellectual disability (Bryant & Charmaz, Citation2007). In keeping with this perspective, we used an exploratory qualitative design using individual and focus group interviews to generate data, and an inductive thematic analysis (Crotty, Citation1998). Approval was given by organisational Human Research Ethics Committees. All participants gave informed consent to be interviewed and the names of organisations and individuals have been changed to preserve anonymity.

Sample and recruitment

Criteria for inclusion were experience of supporting an adult with intellectual disability to make decisions either as a family member or a worker in a disability support service. Information about the project was circulated to key service providers and advocacy groups in the disability sector in Victoria, Australia, through newsletters and email mailing lists. Advertisements invited interested people who met the participant inclusion criteria to contact the research team and participate in either an individual interview or a focus group. Both ways of participating were offered to ensure flexibility and accommodate as far as possible the needs of family members who were providing care for an adult with intellectual disability and who were likely to be drawn from across the wide geographic area of Victoria.

A total of 23 people participated in the study comprising 11 family members, and 12 workers in disability support services. Brief demographic information about participants is included in , but as most of the data collection was through focus groups detailed personal data was not collected about participants. Similarly, we did not collect information about the level of impairment of the people they supported. However, it can be surmised from their accounts of providing support, the verbatim extracts from supporters in the findings and the client profile of the two disability support services involved in the study that most had a mild or moderate level of intellectual disability and used words to communicate.

Table 1. Participants.

Data collection

Eight family members participated in one of two focus groups comprising family members and three participated in an individual interview. Disability workers participated in one of two focus groups made up of paid carers. Focus groups lasted between 30 and 120 minutes, and interviews between 20 and 90 minutes. All the focus group and individual interviews were conducted by the first two authors.

A semi-structured interview schedule with parallel questions tailored to each participant group was used to guide the individual and focus group discussions. Reflecting the methodology the questions were open ended, prefaced by terms such as “how” “can you describe” “what worked well” to avoid prior assumptions about the way support was provided. In order to move from general comments, that may reflect what people think they should say, and gain better insights into participants’ actions, participants were asked to describe in detail particular instances of support and reflect on these in terms of strategies, difficulties, or successes. The broad topics covered were participants’ understanding of new ideas about rights and support for decision making and experiences of providing decision support.

Data analysis

All interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. NVivo was used to manage the data. Data from each participant group were analysed separately using an inductive thematic approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) and line by line grounded theory coding techniques (Charmaz, Citation2006). Initially data were sorted into broad topics using open coding and then focused codes were used to identify themes which were then clustered together into broader thematic categories. Themes were then compared and contrasted across participant groups. During the analytical process the three authors came regularly together as a group to discuss and refine the emergent themes. The emerging themes were also discussed with an expert reference group comprising representatives from service providers and a statewide carers group.

Findings

Three major themes emerged from the analysis. The first captured participants’ underpinning ideas about providing support for decision making, the second identified their approaches to support provision and the third described the challenges they saw themselves as facing. summarises the three themes and subthemes. The perspectives of the two groups of participants, family members and workers, were not always similar, and the analysis draws out the contrasts between them.

Underpinning ideas about support for decision making

Changed perspectives

Few participants were aware of debates, in legal and advocacy spheres, about rights to decision-making support generated by article 12 of the Convention. However, they did perceive that attitudes had changed from the past when the dominant stance had been as one worker said, “oh they’re intellectually disabled; we’ll just make decisions for them.” In talking about this shift, participants recognised the rights of people with intellectual disability to make their own decisions and be accorded the same respect and dignity as other citizens that are embedded in these debates. They said, for example,

The focus is taken off me as an individual or a paid employee and put back on the person that ultimately that decision is going to benefit … . (Worker)

These people are human beings and deserve as much respect and dignity as anybody. (Family member)

… basically whether it is explicit or not, he [service user] doesn’t make decisions for himself. If [at the supermarket he says] “I would like baked beans on toast for tea” and the support worker doesn’t feel like cooking them, he goes “don’t worry mate, we’ll have spaghetti instead”. (Worker)

Integral to day-to-day support

Participants perceived that providing support for decision making was integral to their relationship with the people they worked with or their family member. For example, a family member said, “it’s the stuff we do every day” and a worker said, “you just do it as a matter of course.” The decisions they supported differed in scope, content, and significance, ranging from, what to wear or eat, whether or where a person might work, which day program or class to attend, to decisions about health care, marriage, and leaving home.

Workers also saw that deciding the limits of their decision-making support role was part of their everyday practice; whether they were prepared to become involved in supporting their client with particular types of decisions or if recourse to more formal processes were required. One said, “there are lines … and those lines are there for a reason.” She went on to describe a situation where she had decided it was not legitimate for her to provide support, saying,

I coordinated a house with a female who was going through some … women’s issues … hysterectomy. I was quite new to the role as coordinator … I engaged my manager … We engaged OPA, [the Public Advocate] we got an independent advocate. We ended up going off to VCAT [Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal] and there was a big process involved. And I wouldn’t even contemplate having that decision making put back on to me or anyone in that paid employment. So, no, sorry, not my gig.

Knowing the person well

Participants thought that knowing a person well was a prerequisite for providing support. As one family member said, “to work with the person you’re helping to make the decision you need to have as much information about that person as possible and what their needs are.” For participants knowing a person well, meant understanding their cognitive capacity, life experiences, strengths, weaknesses, and modes of communication. They highlighted too the importance of knowing the more intangible things about a person or the context in which the decision was being made. Talking about knowing the people she supported, one worker said, “she’s a people sort of person, happy to go with the flow” and a family member said, “depends what it is and what else is going on and how stressed she is, when she is really stressed she just can’t think.”

Family members took their knowledge of an individual for granted, given the longevity of their relationship, but suggested workers need to put time and specific effort into getting to know a person. One family member said about her son, “a support worker may take something like six good months to really get to know who he is.” Another described the importance of listening and building up trust,

… there has to be a really big component in listening skills so it is really listening to as wide a range as possible but listening to the people … They really need to listen and build up trust before major decisions are made … . (Family member)

A shared process

Participants thought that decision-making support was a process they shared with many others involved in the life of the person they supported. One worker said, “there’s all these other people that are coming into the picture as well that have an influence.” They recognised that others in a person’s life often had different relationships with them to their own and thus had other perspectives about their preferences. One family member said her daughter, “will tell Sophie [friend] stuff that she won’t tell us so it is helpful to have some insight from others.”

Participants also felt that sharing the process of decision support with others meant that the individual was exposed to differing views which could broaden the options considered. One worker said,

Families are involved in how people ultimately make their decision, other services and stakeholders can be involved … So, it is sort of ensuring that the person has the benefit of all the people that they believe help them to make a decision.

Approaches to providing support

Having a vision – family members

Family members talked about embedding their support for decision making within an overarching vision they held for their family members’ life. They said, for example,

You’ve got to let him do it, which has been our philosophy over the years because we’ve just brought him up as normal. He’s got every chance that everybody else has.

… my view, with or without [name of daughter] input, is very much that within 10 years or even less, I would like to see her working five days a week and if not in some sort of accommodation independently then supported accommodation … she should be working within the community, living within the community, supported as appropriate.

[My daughter should eventually live] in her own flat, her own apartment. But I’ve got to provide seeds for that … . I’m trying to sow those seeds and it sort of sounds very callous but I as a parent have to commit myself to do that so systematically over a period of time she can take on that knowledge or vision gradually. There is a real estate agent who delivers these booklets … full of glossy pages of pictures of apartments and houses and inside them. [Name of daughter] will now look at that book saying “this one looks nice, maybe that’s the one I should have” … she won’t be living anywhere anytime soon, we’re talking a five to eight-year horizon before that happens but that’s the process of making it a tangible visual experience as much as anything else so she can look and see and touch … and actually grasp.

I make sure all the people around her, whether in a recreational setting, educational setting, with friends’ families or our own extended family, they understand what my expectations are.

You have to make sure that every person in that network is absolutely clear about what the end game is, what the vision is and that we’re here to assist [name of person] to go on that journey to the best of her ability.

If we find someone he doesn’t gel with, who is not meeting the goals, we ask them, whoever we’re employing with; we ask “can we have a change?”

Being neutral – workers

In contrast to families, workers did not hold visions for the people they supported but saw their support as being guided by ideas of being neutral. They were aware of their unequal relationship with the people they supported, and as one said, “with great power comes great responsibility.” Workers reflected on how easy it was to influence the direction of a person’s decisions by inserting their own values into the processes of support. They saw this as happening through, the options they presented, the way pros and cons were discussed, their reactions to proposed decisions or even the strength of their relationships with the person. Workers reflected,

I see how much potential I have to influence people’s decision, one of the guys I work with has changed the coffee that he drinks because he drinks the same that I drink now.

… being conscious to not direct them towards what you might think is right for them but rather presenting the information and getting them to get to their own conclusions.

… making sure that I remain really neutral and I don’t express any preferences what so ever.

We’d fight, we’d argue about stuff, but at the end of the day if she said “no”, “no” was the answer.

But I think also that once somebody makes a decision, that it’s really important to remain that way [neutral] because if you’ll go “Oh, fantastic. What a great decision.” They’ll know they’ve made the right one for you, whereas they need to be making the right one for them.

Being realistic

Juxtaposed with the approach of being neutral espoused by workers, both workers and families adopted a stance of being realistic about the support they provided for decision making. This meant applying a layer of realism to an individual’s expectations and the resources likely to be available to implement a decision. Unrealistic expectations referred to included,

… going to Paris for a holiday or America for camp (Worker)

… just deciding you would like to go to a movie with a friend that afternoon when the friend lives on the other side of town. (Family)

… it’s not just simply saying to a person such as my daughter what would you like to do, it’s a matter of curating the options which are appropriate … including providing options which fit. (Family)

… identifying what an issue is for somebody and presenting them with options of what is available to them and what’s achievable and practical for the person (Worker)

… being supportive to point out what is reasonable and possible. (Worker)

… so it is about trying to be real about stuff too and just, this idea you’ve got is a really nice idea but to put it in place you need to think ahead. (Family)

… and another thing that will happen is in a group situation, like five people that we work with, sometimes you’ve got to re- schedule their choice. (Worker)

Family members in particular consciously presented information filtered by their own perspective about the decision that should be made by their relative. One family member said, “we did provide [the information] in such a way that we knew what decision she would make.” Another spoke about how her daughter had been keen to go on a holiday to Bali, but she and her husband knew she would not enjoy it, as she did not like heat, the beach, animals, or spicy food. She recalled saying to her daughter,

These are the sorts of things we’re going to be doing. We’re going to go to the monkey forest, go and look at an elephant, the zoo, we’re going to be eating out a lot, the sorts of food available over there is Indonesian style food and is quite spicy and Bali is an island, we’re going to be going to the beach

Several family members recalled putting a spin on the information they gave in order to delay particular decisions. One mother advised her daughter that if she wanted to leave home she had to “learn, to be independent in cooking and budgeting, paying your bills, learn how to not use too much electricity or gas, cost too much money.” Another recalled a conversation with her daughter’s fiancé that suggested a time frame that would delay the marriage for more than 20 years. She said,

[Fiancé] said when could they get married and they were both there and I said well [daughter] was 32 at the time and he was 18 years older so he was 50 then. So I said “how about when [daughter] is 50, does that sound okay?”

Using practical strategies

Common characteristics associated with intellectual disability were repeatedly highlighted by participants, such as lack of confidence to make decisions, limited experience of options stemming from the low expectations of others and protectionism of past care regimes, difficulties comprehending information about options or consequences of a course of action. The practical strategies they used to overcome these were: (1) attention to communication; (2) education about practicalities and consequences; (3) listening and engaging; and (4) creating opportunities. These are illustrated with quotes from participants in .

Table 2. Practical support strategies.

Challenges for supporters

Managing risks

Participants were positive about providing support for people to make their own decisions, but also saw a need to step in or override their preferences at times in order to manage risks. This was summed up by one family member who said, “[we allow him] to make decisions where he can do it safely.” Other family members said, “[It’s] very difficult there are times when we have to say look this is what you need to do,” and “there are times when we just step in and say no we’re going to make this decision.” Risks primarily revolved around health issues. For example, one mother spoke about taking over when her daughter decided not to have a pacemaker battery replaced because the appointment conflicted with a social engagement,

She said “no way … we have a sausage sizzle at work, I’m not going”. And I said you have to go, your battery will go flat and you’ll drop dead … When her daughter continued to object the mother said she “started digging my heels in” and claimed parental authority, saying “I’m your mother and you’ll do as you’re told”.

… we found out he was throwing out my meals and he was … living on fruit loaf … so we said “no it’s not working when you do things like that”. But he was most adamant wasn’t he so then we had this decision, “I’m sorry mate you’re going to have to come back inside”.

The account given by one worker about a young woman who had epilepsy illustrated some of the tensions workers faced in weighing risk against service user preferences. The young woman had recently had a seizure and a fall and the worker questioned whether she should have avoided the risk of falling,

She had a seizure, and she fell down and she hit her head. And I was working with her, and she didn’t want me right next to her … it was that sort of “Should I have been next to her?” and then it’s like “Nah, I can’t be next to her every single second.” She doesn’t want that … it would drive her nuts to have someone constantly hovering all the time. She’s a 20-year-old. She needs to have her space. And I’m not going to catch her if she goes down anyway … But yeah, she went down very quickly and she did hit her head.

Workers expressed frustration with what they saw as highly risk averse disability support organisations, which at times placed them at odds with both family members and their employers. Some felt that concern about organisational reputation rather than a duty of care lay at the heart of averting risky decisions. As one worker said,

So often Occupational Health and Safety (OH&S) is trotted out or privacy legislation, if I hear that one more time; “Oh no we can’t do it because of the privacy legislation” or “it is an OH&S issue”, those have become big excuses for “we can’t do what people want.

Dealing with conflict

Differing values, approaches of families and workers to decision-making support or managing risk created tensions between them. For example, one worker talked about her frustration when families of the young adults she worked with removed intimate relationships from the decision-making agenda. She said,

we’ve had young people that want to have a relationship with each other … But families have concerns, they have safety issues, they have ideas about what that would mean … it’s easier sometimes to just say “no” rather than negotiate what it would mean for these two people to actually have a relationship.

too often people think they’re being kind to let her have a little treat and little treats only become an iced coffee which is full of ice cream and sugar and I don’t want to be critical of staff because they want to have happy people around them and [daughter] will gravitate to choices which are not going to help her from a health and weight point of view. (Family member)

Although workers talked about using formal processes for decisions they saw as outside their role, no participants talked about using similar processes to resolve conflict among supporters. Rather potential conflict might be avoided by underhand or disrespectful means. One worker said about a family member for instance, “I don’t pay a lot of heed to what she says” and another worker said,

… all you can do is be the portal to that client and what’s best for that client. And sometimes that’s inclusive of their parents. And other times its diplomacy with the parents but still getting the client to where they need to be.

Needing support as supporters

Workers spoke more than family members about their need for support, seeing two aspects to this. First, the opportunity to talk through ethical dilemmas with a supervisor or an external staff counselling service. Support from a supervisor might also be followed up by contact with someone with greater or more relevant expertise. They said, for example,

… generally your first port of contact would be the coordinator. And then the coordinators got to work out which way … or how it’s going to be dealt with … Management could engage external support when required. (Worker)

The line manager [was] stretched over this many houses and they’ve got these new roles and they’re being trained for this and that … and we don’t know if it’s alright to go “ok, go up the next step of the ladder” or phone them, or find another. (Worker)

The second aspect of support was organisational willingness to tackle systemic issues identified by workers. This could include systems for communication among rostered staff and shift flexibility to facilitate support for decision making that might take longer than predicted. Workers said, for example,

What I needed was a communication book because … I’m the staff that’s there today, there’s someone else that’s there tomorrow and another person … . (Worker)

Some things take a lot longer than maybe it would for you or I would to do but time is a different animal. At times that doesn’t fit in well with house timetables or schedules. (Worker)

You need to have good relationships - stronger relationships with the people within the organisation and drop the title. And learn from each other and know each other’s there to communicate. (Worker)

I want the organisation to have that communication process between me and other staff members, the line manager. (Worker)

Discussion

This study did not set out to test support practice against the benchmark of the principles of supported decision making, as these have not been widely disseminated in Victoria, and there is no formal scheme of supported decision making that includes people with intellectual disability. It was not surprising that supporters in this study were unaware of the concept of supported decision making but they were aware of, and endorsed, expectations that people with intellectual disability should have the right to make their own decisions. Both families and workers saw decision support as a shared process, integral to their relationships with the people they supported. However, families were more confident about the breadth of their remit and less likely than workers to consider some decisions may require more formal processes of decision support. Families assumptions about their right to involvement in decision making had led in some instances to tensions with workers. Similar issues of who has the right to be involved in decision support have also arisen in research on decision support for people with acquired brain injury (Knox et al., Citation2015; Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2016c) and the pilot support for decision-making programs in Australia (Bigby et al., Citation2017). This suggests that if more formal mechanisms for decision-making support are created, careful consultation will be important to help families understand any constraints to their support role.

Despite supporters’ comfort with the language of rights, their detailed descriptions about provision of decision support belied a deeper understanding of how this might inform their practice or be compromised. The influence exerted in the processes of decision support was very evident by the way supporters framed particular decisions, presented options and managed risk. In many instances, their actions reflected examples found in the literature of support based on paternalism, best interest, or values and self-interest of the supporter (Dunn et al., Citation2010; Ferguson et al., Citation2011; Rossow-Kimball & Goodwin, Citation2009). Workers appeared more concerned than family members about influencing decisions and their aspirations to be neutral and reflective were similar to the way social workers talk about suspending their own judgments and adopting a neutral and non-judgmental stance to supporting decision making (Ellem, O’Connor, Wilson, & Williams, Citation2013).

The decision support practices identified and the overarching vision for an individual’s life often formulated by families that effectively set the parameters of decision making, illustrate that decision support rests on personal relationships. Practice reflected feminist conceptions of relational autonomy that assert “beliefs, values and decisions that inform autonomous acts are constituted within social relations of interdependence” (Mackenzie & Stoljar, Citation2000). The findings demonstrate the difficulties of remaining neutral in decision support relationships and the very significant challenges of implementing some of the ideals embedded in conceptualisations of supported decision making, such as that envisaged by Silvers and Francis (Citation2009, p. 485) who refer to “prosthetic rationality” suggesting that supporters replace the subjects own thinking process without substituting their own ideas.

Developing visions to guide life directions, support provision and day-to-day decision-making commensurate with an individual’s preference is a longstanding part of support practice with people with intellectual disability, illustrated by the literature on person-centred planning (O’Brien & Lyle O’Brien, Citation2002). However, the findings of this study suggest that visions may be constructed primarily by family members rather than in collaboration with their relatives. This situation raises important questions for policy implementation and further research about the way formal plans are constructed in individualised funding systems such as the NDIS – whether and how effectively these reflect the will and preferences of individuals with intellectual disability rather than those of their families and other supporters? As one of the participants hinted, an annual planning cycle driven by funding agencies provides opportunities for planners to take a pro-active and questioning stance about the centrality of an individual’s preferences to plans and may help enable supporters to reflect on how plans should guide support for decision making.

However, doubts are raised about the influence of plans both on decision support practice by workers (Dunn et al., Citation2010) and the quality of life of people with intellectual disability (Mansell & Beadle-Brown, Citation2004; Ratti et al., Citation2016). Support workers in the present study were not asked directly about the role of plans in guiding decision support but did not make any mention of plans as something informing their approach, suggesting they had little impact on their day-to-day support.

Turning to the processes of decision support, this study found many similarities to the practice of supporters of people with acquired brain injury such as the practical strategies used, need to be realistic, reimage the future and know the person well (Knox et al., Citation2015, Citation2016b, Citation2016c), the latter of which was also found in a study of support for young pregnant women with cognitive disability (Burgen, Citation2010). Reflected in the practical strategies is research specifically about effective approaches to increase the choice making of people with intellectual disability (Cooper & Browder, Citation2001; Fisher et al., Citation2012), support for communication about abstract ideas (Beukelman & Mirenda, Citation2013), and active support practice to enables choice and control about everyday matters (Beadle-Brown et al., Citation2012). The range of practical strategies supporters used also demonstrated a deep understanding about the need to tailor communication and presentation of abstract concepts to reflect the cognitive abilities and experiences of individuals being supported. This suggests the importance of embedding these areas of knowledge in foundation level training to support workers and resources about decision support targeted at workers or families.

These findings illustrate the importance of orchestration, working collaboratively with other supporters, as a principle to inform decision-making support (Douglas, Bigby, Knox, & Browning, Citation2015). The underhand strategies alluded to by some support workers to circumvent the perspectives of families about some decisions of the people they supported are similar to those found in a study of relationships between siblings of older people with intellectual disability and service providers (Bigby, Webber, & Bower, Citation2015). This suggests that strategies to support collaborative working, mediating conflicting ideas, and resolving conflict should be included in resources and support for decision-making supporters.

Workers, in particular, valued assistance from supervisors and others but were concerned about the availability of this type of support. It was not clear from where family members derived support for their role in decision-making support. However, a review of the Australian pilot decision-making programs found that supporters whether family members or volunteers valued assistance from program coordinators to navigate the often complex issues they confronted in providing decision-making support (Bigby et al., Citation2017).

The findings demonstrate how perceptions about available resources or support and issues of risk influence the nature of decision support and curtail options or override preferences of people with intellectual disability. Avoiding premature foreclosure of options, and finding ways to enable risk that minimise harm without changing a person’s preferred choice is a major challenge to be addressed, if a stronger rights-based perspective is to be embedded in the support for decision-making practice of family members and workers. Some work in this sphere, though not yet supported by empirical research is beginning to emerge particularly from the field of dementia (Department of Health, Citation2010).

Limitations

This was a small study capturing the experiences of family members and support workers of people with intellectual disability. Participants self-selected on the basis of their experiences of supporting people with intellectual disability. Family members who participated were exclusively parents and the vast majority (9/11) mothers. Workers included those who provided direct support or were in supervisory roles and did not, for example, include anyone in a paid advocacy role. No criteria were specified about the quality or nature of the support given by supporters and the findings, therefore, reflect the range of approaches to support for decision making rather than being confined to what might be regarded as “good support.” People with intellectual disability in receipt of support were not included as the aim was to understand the experiences of providing support.

Conclusion

This study illustrates the complex and demanding work of supporting people with intellectual disability to participate in decision making. Supporters simultaneously drew on ideas about rights, practicalities, and risks which one likened to “twirling plates on a stick.” The juggling of these three concepts, and the influence exercised by supporters tempered the extent that the will, preferences, and rights of those supported were respected in the decision support process. Although this study was not conducted in a context of a formal supported decision-making scheme or a jurisdiction where its principles have been widely disseminated, these findings illustrate some of the issues of decision support practice that will have to be tackled if supported decision-making principles are more widely adopted. It has pinpointed practical strategies and their underpinning knowledge base used in decision-making support and identified aspects, such as being neutral, managing risk, avoiding influence, and foreclosing options by being realistic too soon, that are more challenging for supporters to navigate than practical support. Strategies for thinking and working through these issues, and for self-reflection on one’s own practice should form the basis for resources developed to train or mentor decision-making supporters about their practice.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of staff members from Scope, Carers Victoria and the Office of the Public Advocate, Victoria who participated in the reference group during the course of this study and supported recruitment of participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Christine Bigby http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7001-8976

Mary Whiteside http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4607-7113

Jacinta Douglas http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0940-6624

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antaki, C., Finlay, W., & Walton, C. (2009). Choices for people with intellectual disabilities: Official discourse and everyday practice. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 6, 260–266.

- Antaki, C., Finlay, W., Walton, C., & Pate, L. (2008). Offering choices to people with intellectual disabilities: An interactional study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52(12), 1165–1175.

- Australian Law Reform Commission. (2014). Equality, capacity and disability in commonwealth laws: Final report. Sydney: Australian Law Reform Commission.

- Bach, M. (2017). Inclusive citizenship: Refusing the construction of “cognitive foreigners” in neo-liberal times. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 4(1), 4–25.

- Bach, M., & Kerzner, L. (2010). A new paradigm for protecting autonomy and the right to legal capacity: Advancing substantive equality for persons with disabilities through law, policy and practice. Toronto: Law Commission of Ontario.

- Beadle-Brown, J. (2015). Supported decision making in the United Kingdom: Lessons for future success. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2(1), 17–28.

- Beadle-Brown, J., Hutchinson, A., & Whelton, B. (2012). Person-centred active support–increasing choice, promoting independence and reducing challenging behaviour. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 25(4), 291–307.

- Beukelman, D. R., & Mirenda, P. (2013). Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (4th ed.). Baltimore, CA: Paul H. Brookes.

- Bigby, C., Bowers, B., & Webber, R. (2011). Planning and decision making about the future care of older group home residents and transition to residential aged care. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(8), 777–789.

- Bigby, C., Douglas, J., Carney, T., Then, S., Wiesel, I., & Smith, E. (2017). Delivering decision-making support to people with cognitive disability – what has been learned from pilot programs in Australia from 2010–2015. Australian Journal of Social Issues. doi: 10.1002/ajs4.19

- Bigby, C., Webber, R., & Bower, B. (2015). Sibling roles in the lives of older group home residents with intellectual disability: Working with staff to safeguard wellbeing. Australian Social Work, 68, 453–468.

- Bonyhady, B. (2016). Reducing the inequality of luck: Keynote address at the 2015 Australasian Society for Intellectual Disability National Conference. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3(2), 115–123.

- Boundy, M., & Fleischner, B. (2013). Supported decision making instead of guardianship: An international overview. Washington: TASC [Training & Advocacy Support Center], National Disability Rights Network.

- Bowey, L., & McGlaughlin, A. (2005). Assessing the barriers to achieving genuine housing choice for adults with a learning disability: The views of family carers and professionals. British Journal of Social Work, 35(1), 139–148.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Brown, I., & Brown, R. I. (2009). Choice as an aspect of quality of life for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 6(1), 11–18.

- Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (2007). Grounded theory in historical perspective: An epistemological account. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The sage handbook of grounded theory (pp. 31–57). London: Sage.

- Burgen, B. (2010). Women with cognitive impairment and unplanned or unwanted pregnancy: A 2-year audit of women contacting the pregnancy advisory service. Australian Social Work, 63(1), 18–34.

- Carney, T. (2013). Participation & service access rights for people with intellectual disability: A role for law? Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 38(1), 59–69.

- Carney, T., & Beaupert, F. (2013). Public and private bricolage-challenges balancing law, services & civil society in advancing CRPD supported decision making. UNSW Law Journal, 36(1): 175–201.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

- Conder, J., Mirfin-Veitch, B., Sanders, J., & Munford, R. (2011). Planned pregnancy, planned parenting: Enabling choice for adults with a learning disability. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(2), 105–112.

- Cooper, K. J., & Browder, D. M. (2001). Preparing staff to enhance active participation of adults with severe disabilities by offering choice and prompting performance during a community purchasing activity. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 22(1), 1–20.

- Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspectives in the research process. London: Allen and Unwin.

- Department of Health, United Kingdom. (2010). Nothing ventured, nothing gained: Risk guidance for people with dementia. London: Department of Health.

- Department of Human Services. (2012). Supporting decision making – a quick reference guide for disability support workers. Melbourne: Disability Services Division Victorian Government.

- Douglas, J., Bigby, C., Knox, L., & Browning, M. (2015). Factors that underpin the delivery of effective decision-making support for people with cognitive disability. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 2, 37–44.

- Dunn, M., Clare, I., & Holland, A. (2010). Living “a life like ours”: Support workers’ accounts of substitute decision-making in residential care homes for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(2), 144–160.

- Ellem, K., O’Connor, M., Wilson, J., & Williams, S. (2013). Social work with marginalised people who have a mild or borderline intellectual disability: Practicing gentleness and encouraging hope. Australian Social Work, 66(1), 56–71.

- Espiner, D., & Hartnett, F. M. (2012). “I felt I was in control of the meeting”: Facilitating planning with adults with an intellectual disability. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40(1), 62–70.

- Ferguson, M., Jarrett, D., & Terras, M. (2011). Inclusion and healthcare choices: The experiences of adults with learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(1), 73–83.

- Fisher, Z., Bailey, R., & Willner, P. (2012). Practical aspects of a visual aid to decision making. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 56(6), 588–599.

- Hawkins, R., Redley, M., & Holland, A. (2011). Duty of care and autonomy: How support workers managed the tension between protecting service users from risk and promoting their independence in a specialist group home. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 55(9), 873–884.

- Healy, E., McGuire, B., Evans, D., & Carley, S. (2009). Sexuality and personal relationships for people with an intellectual disability. Part I: Service-user perspectives. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53(11), 905–912.

- Hodges, J. S., & Luken, K. (2006). Stakeholders’ perceptions of planning needs to support retirement choices by persons with developmental disabilities. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 40(2), 96–106.

- Kjellberg, A. (2002). More or less independent. Disability & Rehabilitation, 24(16), 828–840.

- Knox, L., Douglas, J., & Bigby, C. (2015). “The biggest thing is trying to live for two people”: The experience of making decisions within spousal relationships after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 29(6), 745–757.

- Knox, L., Douglas, J., & Bigby, C. (2016a). “I’ve never been a yes person”: decision-making participation and self-conceptualisation after severe traumatic brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1219925

- Knox, L., Douglas, J., & Bigby, C. (2016b). Becoming a decision-making supporter for someone with acquired cognitive disability following traumatic brain injury. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3(1), 12–21.

- Knox, L., Douglas, J., & Bigby, C. (2016c). “I won’t be around forever”: Understanding the decision-making experiences of adults with severe TBI and their parents. Neuropscychological Rehabilitation, 26(2), 236–260.

- Kohn, N. A., & Blumenthal, J. A. (2014). A critical assessment of supported decision-making for persons aging with intellectual disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 7(1), S40–S43.

- Mackenzie, C., & Stoljar, N. (2000). Autonomy refigured. In C. Mackenzie, & N. Stoljar (Eds.), Relational autonomy. Feminist perspectives on autonomy, agency, and the social self (pp. 3–31). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Mansell, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2004). Person-centred planning or person-centred action? A response to the commentaries. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 17, 31–35.

- Mill, A., Mayes, R., & McConnell, D. (2010). Negotiating autonomy within the family: The experiences of young adults with intellectual disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(3), 194–200.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme Act. (2013). Retrieved from https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2013A00020

- Nota, L., Ferrari, L., Soresi, S., & Wehmeyer, M. (2007). Self-determination, social abilities and the quality of life of people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 51(11), 850–865.

- O’Brien, J., & Lyle O’Brien, C. (Eds.). (2002). Implementing person-centred planning: Voices of experience. Toronto: Inclusion Press.

- Pilnick, A., Clegg, J., Murphy, E., & Almack, K. (2010). Questioning the answer: Questioning style, choice and self-determination in interactions with young people with intellectual disabilities. Sociology of Health & Illness, 32(3), 415–436.

- Ratti, V., Hassiotis, A., Crabtree, J., Deb, S., Gallagher, P., & Unwin, G. (2016). The effectiveness of person-centred planning for people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 57, 63–84.

- Rossow-Kimball, B., & Goodwin, D. (2009). Self-determination and leisure experiences of women living in two group homes. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 26(1), 1–20.

- Series, L. (2015). Relationships, autonomy and legal capacity: Mental capacity and support paradigms. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 40, 80–91.

- Shogren, K. A., & Wehmeyer, M. L. (2015). A framework for research and intervention design in supported decision-making. Inclusion, 3(1), 17–23.

- Silvers, A., & Francis, L. (2009). Thinking about the good: Reconfiguring liberal metaphysics (or not) for people with cognitive disabilities. Metaphilosophy, 40(3–4), 475–498.

- Sims, D., & Gulyurtlu, S. (2014). A scoping review of personalization in the UK; approaches to social work and people with learning disabilities. Health and Social Care, 22, 13–21.

- Sowney, M., & Barr, O. (2007). The challenges for nurses communicating with and gaining valid consent from adults with intellectual disabilities within the accident and emergency care service. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(9), 1678–1686.

- Stainton, T. (2016). Supported decision-making in Canada: Principles, policy and practice. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 3(1), 1–11.

- Then, S. (2013). Evolution and innovation in guardianship laws: Assisted decision-making. Sydney Law Review, 35(1), 133–166.

- Tideman, M. (2016, November 18). Swedish “god man”: An unique supported decision making system – but does it work? Paper presented to the Living with Disability Research Center Roundtable: Supporting people with cognitive disabilities with decision making, Melbourne.

- Timmons, J. C., Hall, A. C., Bose, J., Wolfe, A., & Winsor, J. (2011). Choosing employment: Factors that impact employment decisions for individuals with intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 49(4), 285–299.

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2006). Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- Wennberg, B., & Kjellberg, A. (2010). Participation when using cognitive assistive devices – from the perspective of people with intellectual disabilities. Occupational Therapy International, 17(4), 168–176.

- Willner, P., Bailey, R., Parry, R., & Dymond, S. (2010). Evaluation of the ability of people with intellectual disabilities to “weigh up” information in two tests of financial reasoning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(4), 380–391.