Abstract

The dipeptide aspartame (Asp-Phe-OMe) is a sweetener widely used in replacement of sucrose by food industry. 2′,6′-Dimethyltyrosine (DMT) and 2′,6′-dimethylphenylalanine (DMP) are two synthetic phenylalanine-constrained analogues, with a limited freedom in χ-space due to the presence of methyl groups in position 2′,6′ of the aromatic ring. These residues have shown to increase the activity of opioid peptides, such as endomorphins improving the binding to the opioid receptors. In this work, DMT and DMP have been synthesized following a diketopiperazine-mediated route and the corresponding aspartame derivatives (Asp-DMT-OMe and Asp-DMP-OMe) have been evaluated in vivo and in silico for their activity as synthetic sweeteners.

Introduction

The low-calorie sweetener aspartame, namely aspartyl-phenylalanine methyl ester, is a common synthetic dipeptide ester which possesses a sweetening power around 200 times sweeter than sucrose. Considering its commercial importance in food industry, its safety has been widely investigated by studies in several human subpopulations, including healthy people, obeses, diabetics, etc. and its massive use has been recently criticized basing on a theoretical toxicity of its metabolic components, namely aspartate, phenylalanine and methanol. Nonetheless, additional research has been carried out to understand the possible association between aspartame and headaches, seizures, behaviour, cognition, and mood as well as allergic-type reactions. The question about its safety remains still unresolvedCitation1.

The detection of sweet-tasting compounds (carbohydrates and non-caloric sweeteners) is mediated by a heterodimeric receptor composed of two subunits, namely T1R2 and T1R3. Moreover, this receptor modulates glucose transporters and glucose homeostasis in other “non-taste” organs (gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, bladder, adipose tissues, and brain) demonstrating to show a potential as new therapeutic targetCitation2,Citation3. Small molecule inhibitors of sweet receptors have been demonstrated to reduce glucose absorption and calorie uptake providing an alternative strategy for the treatment of obesity and its related diseases.

Several structure–activity relationship studies have been conducted on aspartame derivativesCitation4–6, but none of them have explored the importance of the side chains orientation of the phenylalanine residue in influencing the sweet potency and the taste quality. It is well known that the incorporation of unnatural amino acids into bioactive peptides may lead to unique analogues, biologically more active and/or more selective than the parent peptidesCitation7. This is the result of strong modifications on the stereoelectronic properties of the peptide and of the secondary structure, as the stabilization of a folded conformation. Lately, it has been proved that the arrangements of the side chains of the residues are also important for the binding with the target molecules. For example, the introduction of 2′,6′-dimethyltyrosine (DMT) in place of the native TyrCitation1 in endomorphin-1 yields a very potent analogue at the µ opioid receptor and a similar effect has been reported for the incorporation of 2′,6′-dimethylphenylalanine (DMP) in place of C-terminus PheCitation8,Citation9. This behaviour can be explained with the concept of χ spaceCitation10–12. In fact, side chains of natural amino acids possess a certain degree of flexibility around the χ dihedral angles, which allows the peptide to adapt its overall 3D shape to different receptors. In order to enhance potency and efficacy, the side chain’s freedom of the native residue may be reduced in order to obtain a more favourable topology. Plotting energy versus χ dihedral angle is available in the Supplemental material. Considering the recent applications of this approach in peptidomimetics designCitation13,Citation14, in this paper, we synthesized two new aspartame models in which the native phenylalanine residue was substituted by two constrained aromatic surrogates, namely 2′,6′-dimethyltyrosine and 2′,6′-dimethylphenylalanine.

In 2010, an effort was done to elucidate the molecular mechanism of the sweet taste enhancers. Umami and sweet taste receptors share a T1R3 subunit as a common subunit. It has been shown that the sweet enhancers have no effect on umami taste receptor. So, they probably bind to the N-terminal extracellular domain of T1R2 subunit. This subunit is composed of two distinct domains, Venus flytrap (VFT) and transmembrane domain, as present in T1R family receptors. Generation of hybrid receptors showed that the interaction mode of some enhancers is mediated by VFT domain of T1R2 subunitCitation15. As a consequence, bioactivity and in silico evaluation of the binding mode of both derivatives have been explored using an established receptor model.

Materials and methods

Chemistry

The structure of the intermediates and the final compounds was confirmed by 1H NMR spectra recorded on a 300 MHz Varian Inova spectrometer (Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA). Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (δ) downfield from the internal standard tetramethylsilane (Me4Si). Homogeneity was confirmed by TLC on silica gel Merck 60 F254 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The HR ESI-MS experiments were performed on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). The MS was operated in the positive mode. The parameters used were the following: capillary temperature 220 °C, spray voltage 2.3 kV, and sheath gas 5 units.

Solutions were routinely dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 prior to evaporation. Chromatographic purifications were performed for the intermediate products by Merck 60, 70–230 mesh silica gel column and for the final products 4a and 4b by RP-HPLC. All chemicals used were of the highest purity commercially available.

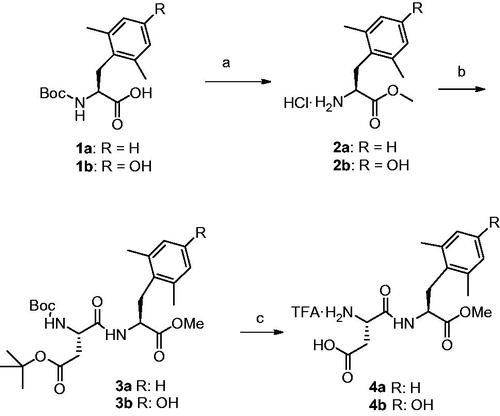

All dipeptides were synthesized by solution phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) using Boc strategy following well-established proceduresCitation16. Nα-Boc deprotection was carried out by TFA treatment. DMP (1a) and DMT (1b) were synthesized following the method developed by Mollica and Costante (Patent Application “Sintesi enantioselettiva di amminoacidi aromatici non-naturali”, Application Number: RM2015A000091, date: 27/02/2015) and transformed in methyl ester hydrochlorides 2a and 2b by treatment with SOCl2 in MeOH, and used without further purification for the next stepCitation16b (Scheme 1).

Boc-Asp(tBu)-DMP-OMe (3a)

Boc-DMP-OH (1a) was dissolved in MeOH, then SOCl2 (2 eq.) was added dropwise at 0 °C. The mixture was allowed to warm to r.t. and stirred for 3 h, then the solvent was removed in vacuo to give HCl·H-DMP-OMe (2a) which was used for the next reaction without further purification. Coupling with Boc-Asp(tBu)-OH was performed following the general coupling procedure. After silica gel chromatography using CH2Cl2/EtOAc (from 95:5 to 85:15) as eluent, the pure dipeptide was obtained as a colorless oil in 65% yield. HRMS calcd.: 478.2679, found: 478.2687. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.11 (1H, d, DMP NH), 7.05–6.97 (3H, m, Ar), 5.54 (1H, d, BocNH), 4.77–4.69 (1H, m, Asp αCH), 4.42–4.35 (1H, m, DMP αCH), 3.59 (3H, s, OMe), 3.08–2.87 (2H, m, DMP βCH2), 2.84–2.51 (2H, m, Asp βCH2), 2.34 (6H, s, DMP CH3), 1.43, and 1.46 (18H, s, Boc, OtBu).

TFAċH-Asp-DMP-OMe (4a)

Nα-Boc and OtBu deprotections of compound (3a) were performed as reported for TFA·H-Val-Gly-OMe. The crude product was purified by RP-HPLC semi-preparative C18 column (eluent: ACN/H2O gradient, 5–80% over 20 min) and the TFA salt was obtained, after freeze drying, in quantitative yield as a white powder. HRMS calcd.: 322.1529, found: 322.1535. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 8.98 (1H, d, DMP NH), 7.00–6.98 (3H, m, Ar), 4.86–4.60 (1H, m, Asp αCH), 4.09–4.05 (1H, m, DMP αCH), 3.50 (3H, s, OMe), 3.15–2.70 (4H, m, DMP βCH2, Asp βCH2), 2.52 (6H, s, DMP CH3).

Boc-Asp(tBu)-DMT-OMe (3b)

HCl·DMT-OMe (2b) and Boc-Asp(tBu)-DMT-OMe (3b) were synthesized as reported for compound (3a) and, after column chromatographic purification, the dipeptide was obtained as a colourless oil in 85% yield. HRMS calcd.: 494.2628, found: 494.2640. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ: 7.88 (1H, d, DMT NH), 6.50 (2H, s, Ar), 5.46 (1H, d, BocNH), 4.68–4.55 (1H, m, Asp αCH), 4.32–4.25 (1H, m, DMT αCH), 3.64 (3H, s, OMe), 3.40–2.21 (2H, m, DMT βCH2), 2.92–2.56 (2H, m, Asp βCH2), 2.28 (6H, s, DMT CH3), 1.44, and 1.42 (18H, s, Boc, OtBu).

TFA H-Asp-DMT-OMe (4b)

Nα-Boc and OtBu deprotections of compound (3b) were performed as reported for compound 3a. The crude product was purified by RP-HPLC semi-preparative C18 column (eluent: ACN/H2O gradient, 5–80% over 20 min) and the TFA salt was obtained in quantitative yield as a white powder after freeze drying. HRMS Calcd.: 338.1478, found: 338.1489. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ: 9.14 (1H, s, DMT OH), 8.84 (1H, d, DMT NH), 6.40 (2H, s, Ar), 4.56–4.41 (1H, m, Asp αCH), 4.10–3.96 (1H, m, DMT αCH), 3.53 (3H, s, OMe), 3.15–2.56 (4H, m, DMT βCH2, Asp βCH2), 2.12 (6H, s, DMT CH3).

NMR conformational studies

To gain further information on the preferred conformation of the models, we examined the 2D ROESY 1H NMR of aspartame and [DMP2]aspartame. As shown in and , aspartame and [DMP2]aspartame derivatives show strong sequential NOEs Phe NH–Phe CHα. This effect can be observed for both products. Some differences can be appreciated in the NOEs between the aromatic ring protons and the backbone of the peptides of aspartame, and the NOEs between the Ar–CH3 protons and the backbone of the [DMP2]aspartame. These data strongly suggest that the aromatic ring of the DMP model is restricted into a well-defined χ angles, according to the computational energy calculation. All 1D and 2D 1H NMR experiments were performed at 300 MHz on a Varian Inova NMR spectrometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) with a constant temperature at 298 K. The ROESY spectra were obtained using standard pulse programs, with a mixing times of 300 ms, t1 = 1.5 s. The 2D NMR matrixes were created and analyzed using the Agilent WNMR computer program (Agilent Technologies Inc., Atlanta, GA). Each two-dimensional spectrum was acquired in a 1024 × 1024 data matrix complex points in F1 and F2. Zero filling in F1 and sine windows in both dimensions was applied before Fourier transformation. Chemical shifts (δ) are quoted in parts per million (ppm) downfield from tetramethylsilane, and values of coupling constants are given in Hz.

Figure 1. Relevant interproton correlations as deduced by ROESY experiments of aspartame and [DMP2]aspartame.

![Figure 1. Relevant interproton correlations as deduced by ROESY experiments of aspartame and [DMP2]aspartame.](/cms/asset/02de0ef2-70da-4c17-8b2e-8845ed6e6ec6/ienz_a_1076811_f0001_b.jpg)

Table 1. Observed NOE Cross Peaks and intensities of aspartame and [DMP2]aspartame in DMSO-d6 and J coupling constants (Hz)a.

Sensory evaluation

Standard [DMT2]aspartame and [DMP2]aspartame were synthesized and tested as TFA salts as reported by Dörrich et al.Citation17 Qualitative taste assays were carried out following the protocol reported by the same authorCitation17. We conduct our studies in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. TFA.Aspartame, commercial aspartame, [DMT2]aspartame and [DMP2]aspartame were tasted by three volunteers in blind tests using diluted aqueous solutions of each test compound. Different concentrations (between 0.1 and 0.001% (w/v)) of each dipeptide were evaluated at 3–5 min intervals. About 1.5 mL of each solution was applied via pipettes and allowed to flow over the volunteer’s tongue for 3 s and then washed out. Sweetness intensities were determined relative to aqueous sucrose solutions of 0.5, 2.0, 4.0, and 8.0% (w/v) as the reference. The [[DMT2]aspartame and [DMP2]aspartame solutions resulted to be tasteless even at the higher concentration. The absence of taste of the novel synthesized aspartame analogues was the object of the in silico investigation.

Computational experiments

Sequence alignment

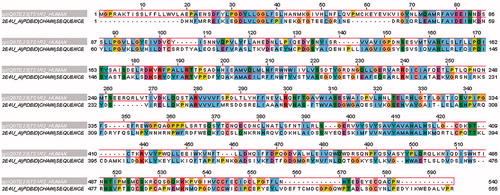

Due to the lack of experimental data, a three-dimensional structure of sweet T1R family receptors, the 3D structure of extracellular VFT domain of T1R2 was constructed by homology modelling (). In the first stage, the amino acid sequence of human T1R2 was retrieved from Swiss–Prot database with the accession number Q8TE23. Then, the BLAST search engine from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) was utilized to find the suitable template with pdb format. Among the listed templates, crystal structure of the extracellular region of the group II metabotropic glutamate receptor complexed with l-glutamate (pdb code: 2E4U) with resolution 2.35 Å, was used as a templateCitation18. Alignment between query sequence and selected template was done by ClustalW2 from its websiteCitation19,Citation20 with default parameters. Produced alignment, which showed 28% identity, was used for 3D model building.

T1R2 model building by homology modeling

To construct the T1R2 models, MODELLER 9v14 package (Andrej Sali Lab, San Francisco, CA) was employed. Using this package, one hundred models of human T1R2 were constructed and to select the best model, the one with the lowest value of Discrete Optimized Protein Energy (DOPE)Citation21 was picked. The final model was minimized by the steepest descent algorithm implemented in GROMACS 4.5 packageCitation22. The Ramachandran plots of models also were computed by PROCHECK to assess the psi and phi angles of model residues and clarify the model qualityCitation23.

Docking study of T1R2 model and ligands

To dock the aspartame, DMP and DMT into the binding site of T1R2 model, AutoDock Vina was employedCitation24. This molecular docking software profits of knowledge-based potentials and empirical scoring functionsCitation24,Citation25. To generate the 3D structures of ligands, PRODRG server was utilizedCitation26. After generation of 3D structures of aspartame, DMP and DMT, their non-polar hydrogen atoms were deleted and subsequently, Gasteiger–Marsili charges were assignedCitation27. For protein preparation before docking study, Gasteiger–Marsili charges implemented in Autodock Tools 1.5.4 were allocated for T1R2 model. To assess the binding affinity of ligands to the T1R2 binding site, a box with a grid map with 30 × 30 × 30 points and grid-point spacing of 1 Å was set up at the geometrical center of the residue Asp 278. For all docking runs, a default value of exhaustiveness parameter was assigned. All poses were re-clustered with x-score v1.1 and one with the highest average score was saved for further analysis and studies. The three scoring functions of X-score have been calibrated with a large training set of 800 protein–ligand complexes. Thus, it can be applied to a wider range of biomolecular systems giving more robust resultsCitation28.

Molecular dynamic simulations

Following the molecular docking, molecular dynamic (MD) simulations were done for T1R2, T1R2:aspartame, and T1R2:DMP complexes. All MD simulations were executed in periodic boundary conditions (PBC), using GROMOS96 43A1, a united atom force field, by GROMACS 4.5 package. To check the ionization state of ionizable residues, PROPKA 2.0 was used and the correct states were assigned for themCitation29. GROMACS parameters of aspartame, DMP and DMT, were generated by PRODRG serverCitation26. To increase the precision in charge assignment, the atom charges of aspartame, DMP and DMT, were determined from the equivalent functional group in a GROMACS-building block fileCitation30,Citation31. Eleven Na+ counter ions were added to all systems to neutralize the negative charges. During the minimization, the protein non-hydrogen atoms were kept fixed in their initial configuration. After neutralization, all systems were introduced to the steepest descent minimization algorithm with an energy step size of 0.01. The minimization was converged when the maximum force was smaller than 10.0 kJ/mol. Successively, position restraint procedure was carried out in association with temperature coupling (NVT)Citation32 and pressure coupling (NPT) ensemblesCitation33. For each system, two coupling groups including protein (or protein ligand), solvent and ions were assigned. These groups were equilibrated separately at 300 K with a coupling constant of 0.1 ps and time duration of 100 ps. For NPT equilibration, a pressure of 1 bar, a time duration of 100 ps, and a time constant of 2 ps were allotted. In both ensembles mentioned above, PME method, with an interpolation order of 4, was used to compute the long-range electrostatic interactionsCitation34. LINCS algorithm was used to constrain covalent bond lengthCitation35. The short-range neighbor list, short-range electrostatic, and short-range van der Waals cut-offs were set to 1.2 nm. For all MD runs, a 30 000 ps molecular dynamics was accomplished on the entire system. The trajectories were analyzed using the standard tools implemented in the GROMACS package.

Calculation of binding free energy

Modified Molecular Mechanics–Poisson Boltzmann Surface Area (MM-PBSA) methodCitation35 was used to compute the interaction free energy between DMP and DMT with T1R2, separately. In this method, based on its theory, the free energy of binding can be expressed as follows:

where Gcomplex is the total free energy of the protein–ligand complex and Gprotein and Gligand are total free energies of the separated form of protein and ligand in solvent, respectively. In our study, van der Waals, Electrostatic, Polar solvation, the solvent accessible surface area, solvent accessible volume y and Weeks–Chandler–Andersen energies were computed by g_mmpbsaCitation36.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

DMP and DMT have been synthesized following the method licensed by Mollica and Costante (patent titled “Sintesi enantioselettiva di amminoacidi aromatici non-naturali”, Application Number: RM2015A000091, date: 27/02/2015) and their chemical–physics parameters were equal to those of the commercial products. Boc-DMP-OH and Boc-DMT-OH were converted into the corresponding methyl esters hydrochloride by treatment with SOCl2 in MeOHCitation16b,Citation37. The so obtained building blocks were coupled in the next step to Boc-Asp(Otbu)-OH. The protected aspartame derivatives were then purified by silica gel chromatography and deprotected by TFA in CH2Cl2. TFA salt were purified by RP-HPLC, C18 (ACN/H2O, gradient, 1% TFA).

Computational modelling of T1R2

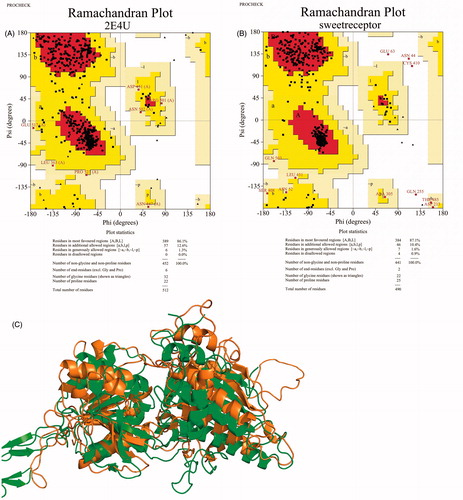

The VFT domain of T1R2 subunit was modeled by the homology modeling method to investigate the interaction mode of aspartame, DMP and DMT. Sequence alignment between VFT domain of T1R2 and the template (2E4U) is shown in . The residues with same physicochemical properties are shown in same color. The selected template is an extracellular region of metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)Citation18. All mGluRs have also the N-terminal ligand-binding domain, which is often called the VFT moduleCitation38,Citation39. An agonist is included in the template pdb file, which can help to model the orientation of T1R2 active site. The best template selected by BLAST had just 28% identity. Because of low identity between the template and query sequence, validation of the generated 3D model is necessary to elucidate the model validity. Thus, the quality of the model was evaluated by PROCHECK.

As shown in , 86.1% of template residues are located in favored core regions with no one in disallowed region. For our model, in comparison with the template, a bit more residues are located in core regions (87.1) with a relatively low percentage of residues 1.3% in generously allowed regions and 0.9% in disallowed regions. For acceptable structures, it is expected that more than 85% of residues fall into the core regions. The second set of parameters, Goodness factor, was evaluated and summarized in . Reasonable values of G-factor in PROCHECK are between 0 and −0.5 with the best models exhibiting values close to zeroCitation40. The overall G-factor for TIR2 model (−0.16) shows a good and acceptable quality.

Table 2. Stereo-chemical quality of template and model checked by PROCHECK.

Ramachandran plots of template and T1R2 model are shown in , respectively. As seen in , 97.5% of T1R2 model residues were either in the most-favored regions or the additionally allowed regions. Moreover, shows the superposition of the template and T1R2 model. The most conformational differences between the template and T1R2 are related to loops.

Figure 3. Ramachandran plot of template (2E4U) (A), TIR2 model (B), and cartoon view of superposition of template and TIR2 model (C). In the superimposed image, template and TIR2 model are shown in green and brown, respectively. (Colors in this figure are referred to the web version of this article.)

Molecular docking analysis

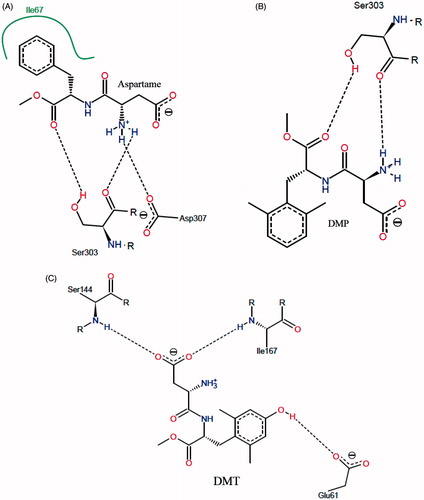

Molecular docking of aspartame, DMP and DMT, was performed to evaluate the potential binding modes of the three peptide derivatives. The docking results were clustered and screened based on the algorithm of binding energy calculation implemented in AutoDock Vina. shows the interaction mode between aspartame and T1R2 model. Within a hydrophobic pocket of T1R2, Ile67 forms a hydrophobic interaction with the phenyl moiety of aspartame. Also, hydroxyl and carbonyl moieties of Ser303 interact with carbonyl and amino groups of aspartame via hydrogen bonding, respectively. Carboxyl moiety of Asp307 can form a salt bridge with of aspartame. In 2006, Cui et al., based on a homology modeling study, demonstrated that Asp307 and Ser303 are the main residues involved in interaction with aspartame, due to the formation of hydrogen bonding and salt bridgingCitation41. Zhang et al. showed that Lys65, Leu279, Asp278, and Asp307 of T1R2 interact with the enhancer SE-3Citation15. It seems that the interaction mode of DMP with T1R2, in comparison with aspartame, is slightly different (). The bulkier aromatic ring of DMP prevents to form a hydrophobic interaction. Based on this behaviour, Ser303 interacts with DMP through hydrogen bonding. In contrast to aspartame and DMP, DMT binds to T1R2 with a completely different pattern. With regard to , NH of Ser144 and Ile167 formed a hydrogen bond with the carboxyl moiety of DMT. An additional hydrogen bonding is formed between carboxyl moiety of Glu 61 and hydroxyl group of DMT. Based on our docking study, the only hydrophobic interaction of the binding site is present in T1R2:aspartame complex. For further analysis, aspartame and DMP were selected to perform MD simulation.

Figure 4. (A) Schematic two-dimensional representations of the binding interactions between aspartame and binding site of T1R2 model. Black dashed lines are hydrogen bonds. Hydrophobic interactions are shown by green solid line; (B) schematic two-dimensional representations of the binding interactions between DMP and binding site of T1R2 model. Black dashed lines are hydrogen bonds; (C) schematic two-dimensional representations of the binding interactions between DMT and binding site of T1R2 model. Black dashed lines are hydrogen bonds. (Colors in this figure are referred to the web version of this article.)

Molecular dynamic simulation

Protein folding, enzymatic reaction, molecular recognition, and substrate–receptor bonding take place as a result of inter and intra-molecular interactions between biomacromolecules and ligands. MD simulation of the biological process is a powerful tool to generate such information at the microscopic level. In this stage, MD simulations of free T1R2, T1R2:aspartame and T1R2:DMP complexes were done to demonstrate and elucidate the mode of interaction between peptides and T1R2 during 30 ps. In addition, binding free energy and receptor conformational changes in the absence and presence of peptides were investigated.

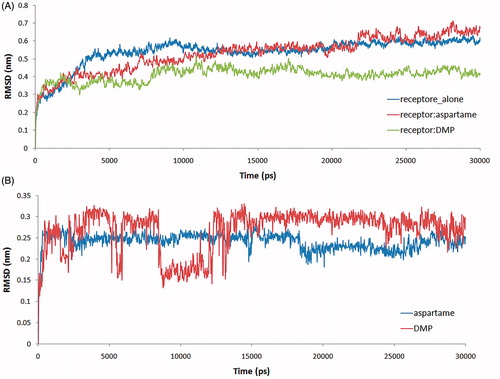

Root mean square deviation (RMSD)

To assess the equilibration of MD trajectories, RMSD is considered a crucial parameter. RMSD values of the backbone atoms of T1R2 are plotted as a function of time to verify the stability of each system during 20 ps MD simulation. The RMSD values of free T1R2, T1R2:aspartame and T1R2:DMP complexes are shown in . RMSD values of free T1R2 are increased up to 0.6 nm at 9100 ps. After a short decrease of RMSD to 0.53 nm, the system is equilibrated at the last 10 000 ps. In the case of T1R2:aspartame complex, RMSD is variable between 0.3 and 0.7 nm. Steady increase of RMSD is occurred till 21 700 ps. RMSD value for T1R2:DMP complex is between 0.2 and 0.48 nm. After increasing up to 0.44 nm at 7900 ps, the system approximately is equilibrated till 30 000 ps. It seems that binding of the DMP to T1R2 decreases the backbone flexibility of T1R2 and preserves it in a “rigid state”. Conversely, binding of aspartame to T1R2 can promote some backbone flexibility, which may be necessary to form the active T1R2:T1R3 heterodimer. The RMSD values of aspartame and DMP to T1R2 model were acquired on the MD simulation of two systems to get information on position fluctuations. As shown in , the RMSD of aspartame atoms rose to 0.26 nm after 300 ps and then leveled off to 0.25 nm. In the case of DMP, RMSD increased up to 0.3 nm, then a short decreasing to 0.15 nm is occurred and finally, the atoms were equilibrated approximately at the second half time of MD simulation. In comparison with DMP, aspartame has been reached to equilibrium more quickly.

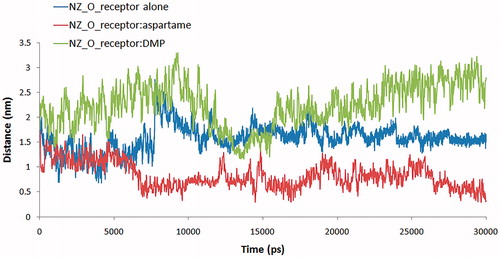

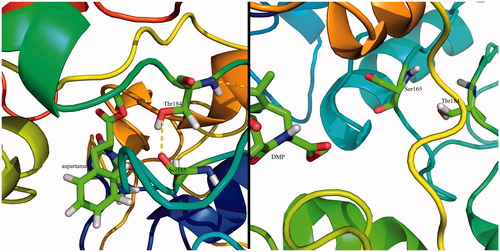

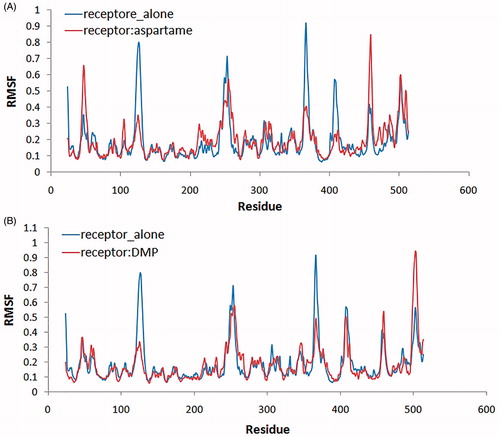

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and induced conformational changes

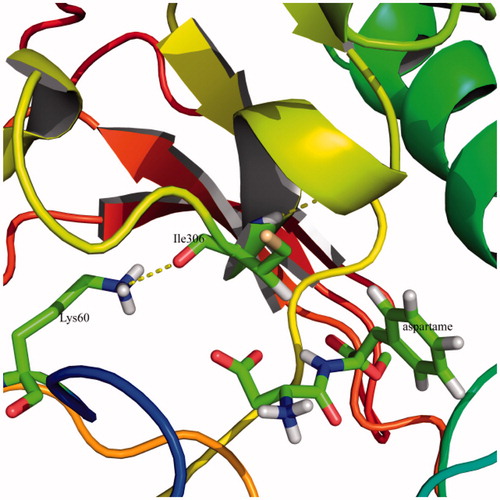

RMSF computation with respect to the average MD simulation conformation can be used to evaluate and assess the flexibility differences among residues. shows the backbone RMSF versus residue number. In , RMSF of free T1R2 against T1R2:aspartame complex is depicted. In addition, RMSF of free T1R2 against T1R2:DMP complex is shown in . VFT domain of T1R2 consists of two globular sub-domains joined by a three-stranded flexible hingeCitation14. The first connection flexible strand is composed of Thr183, Thr184, Pro185, and Ser186 with RMSF values of 0.972, 1.093, 1.208, and 1.208 Å, respectively. These values approximately remained unchanged in T1R2:DMP complex (). In the case of T1R2:aspartame complex, these values are increased up to 1.156, 1.238, 1.405, and 1.412 Å (). The second strand is made of Ala445, Leu446, His447, and Leu448. These residues connect the two β-sheets belonging to sub-domains. Gly324, Ile325, Thr326, Ile327, and Gln328 form the third strand. Based on our data, RMSF of all three strand residues of T1R2:aspartame complex, in comparison with free T1R2 and T1R2:DMP complex, are increased. So, the mentioned “hinge” may have a critical role in T1R2 conformational changes and causes emerging the sweat taste response. Moreover, some researchers claimed that brazzein, a well-known sweet-tasting protein, binds to the “hinge” region of T1R2Citation42. Previously, it has been shown that the “hinge” region of metabotropic glutamate receptors allows T1R2 conformational changes between open and closed conformationsCitation43. Sweet taste receptors have the highest similarity with metabotropic glutamate receptors in “hinge” regionCitation15,Citation42. Thus, these “open” and “close” conformational changes can be true for our T1R2 model. Based on our MD simulations, binding of aspartame to VFT domain triggers some conformational changes. As shown in , side chain NH3 of Lys60 from upper lobe interacts with backbone carbonyl moiety of Ile306 belonging to lower lobe via hydrogen bonding. This interaction can be inspected during 30 ns MD simulation. exhibits the distance between a nitrogen atom of Lys60 and oxygen of Ile306. For free T1R2, the distance is about 13 Å till 7.4 ns. Then, increased up to 24 Å and followed by a reduction to 14 Å. In the case of T1R2:aspartame complex, after a steady variation about 5.4 Å, it fell down to 2.9 Å. In an opposite manner, for T1R2:DMP complex, after a short fall between 11 and 15 ns, the distance increased up to approximately 29 Å. Due to binding of aspartame to the T1R2 model, a hydrogen bonding is formed between backbone carbonyl moiety of Ser165 and hydroxyl moiety of Thr184 (). In the presence of DMP in binding site of T1R2 model, these residues are too far to be able to interact to gather ().

Figure 6. (A) RSM fluctuation of residues during MD simulation. RMSF comparison between free T1R2 (blue line) and T1R2:aspartame complex (red line); (B) RMSF comparison between free T1R2 (blue line) and T1R2:DMP complex (red line). (Colors in this figure are referred to the web version of this article.)

Figure 7. The computed binding mode of Lys60 with Ile306 in the binding site of T1R2 model. The hydrogen bonds are shown by the yellow dashed lines. (Colors in this figure are referred to the web version of this article.)

High-throughput MM-PBSA for binding free energy calculations

To estimate the interaction free energy between aspartame/DMP and VFT domain of the T1R2 model, MM-PBSA method was usedCitation36. Recently, a combination of MM-PBSA and molecular dynamic method has been used to re-score the docked poses. By applying this new method, the scoring function has been increased significantlyCitation44–46. The snapshots were extracted from the last 10 ns of MD trajectories for the analysis of the binding free energy. In , the binding free energy of aspartame and DMP to T1R2 model is −86.539 and −39.61, respectively. Based on our results, van der Waals energy is the most effective energy, which favors the binding of aspartame and DMP to binding site of T1R2 model. As shown in , binding of DMP, in comparison with aspartame, increases the van der Waals and electrostatic energies. Thus, increasing the hydrophobicity of aspartame opposes to the binding. This result suggests that the optimizations of van der Waals interactions between the agonists and T1R2 model may lead to the potent sweeteners.

Table 3. Molecular energy terms for the T1R2:aspartame and T1R2:DMP complexes.

Conclusion

Conformational constricted amino acids are important tools to explore the topographical preferences of bioactive peptides. DMP and DMT, in particular, have been recently used in the field of opioid peptides together with ΔzPhe and other constrained residues with remarkable resultsCitation11. Using our recent developed method to gain access to DMT and DMP and their N- or C-terminal protected derivatives, we have incorporated these two amino acids as phenylalanine surrogates in aspartame. The effects of this approach on the sweetener power have been evaluated. Our experiments demonstrated that DMP and DMT in place of native Phe in aspartame gave tasteless compounds. To further explore this result, a receptor model was built by homology in order to gain information about the binding mode of two aspartame models, and their lack to stimulate efficiently the sweet receptors (T1R2). Our data indicated that both phenylalanine-constrained surrogates, once inserted in the backbone of aspartame, deeply modify the binding mode at the T1R2 receptor model. In particular, by a comparison of the RMSD obtained by molecular dynamics simulations with of the aspartame derivatives bound to the receptor model, it is clear that native aspartame binds to the receptor in a unique way. We further confirmed our findings by RSM fluctuation of residues during MD simulation and more confirmations of these results were gained by measuring the distance changes between the ɛ nitrogen atom of Lys60 and oxygen of Ile306 in free T1R2, T1R2 complexed to aspartame and T1R2 complexed to DMP during MD simulation. Molecular docking also gave different binding properties for aspartame and its DMP analogue. The computed binding modes of Ser165 with Thr184 in the binding site of T1R2 model are very different in T1R2 complexed with aspartame and T1R2 complexed with DMP. Also 2D Roesy experiments were carried out. All those data are consistent with the hypothesis that the substitution of the native Phe of aspartame with conformational constrained residues such as DMP or DMT changes the conformational and stereo-electronic properties of aspartame. The overall 3D shape and conformational changes do not consent to the proposed molecules to correctly positioning in the binding pocket of the receptor, with a final lack of the signal transduction.

Supplementary material available online

IENZ_1076811_Supp.pdf

Download PDF (361.8 KB)Declaration of interest

The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Butchko HH, Stargel WW, Comer CP, et al. Aspartame: review of safety. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2002;35:S1–93

- Laffitte A, Neiers F, Briand L. Functional roles of the sweet taste receptor in oral and extraoral tissues. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2014;17:379–85

- Sigoillot M, Brockhoff A, Meyerhof W, Briand L. Sweet-taste-suppressing compounds: current knowledge and perspectives of application 2012;96:619–30

- Avenoza A, Parísa M, Peregrina JM, et al. Aspartame analogues containing 1-amino-2-phenylcyclohexanecarboxylic acids (c6Phe). Tetrahedron 2002;58:4899–905

- Formaggio F, Crisma M, Valle G. Conformationally restricted analogues of anti-aspartame-type sweeteners. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 2 1992;2:1945–50

- Walters DE, Prakash I, Desai N. Active conformations of neotame and other high-potency sweeteners. J Med Chem 2000;43:1242–5

- Hruby VJ, Cai M. Design of peptide and peptidomimetic ligands with novel pharmacological activity profiles. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2013;53:557–80

- Li T, Shiotani K, Miyazaki A, et al. Bifunctional [2′,6′-dimethyl-l-tyrosine1]endomorphin 2 analogues substituted at position 3 with alkylated phenylalanine derivatives yield potent mixed µ-agonist/δ-antagonist and dual µ-agonist/δ-agonist opioid ligands. J Med Chem 2007;50:2753–66

- Harrison BA, Pasternak GW, Verdine GL. 2,6-Dimethyltyrosine analogues of a stereodiversified ligand library: highly potent, selective, non-peptidic µ opioid receptor agonists. J Med Chem 2003;46:677–80

- Stefanucci A, Pinnen F, Feliciani F, et al. Conformationally constrained histidines in the design of peptidomimetics: strategies for the χ-space control. Int J Mol Sci 2011;12:2853–90

- Torino D, Mollica A, Pinnen F, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of new endomorphin analogues modified at the Pro2 residue. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2009;19:4115–18

- Torino D, Mollica A, Pinnen F, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of new endomorphin-2 analogues containing (Z)-α,β-Didehydrophenylalanine (ΔZPhe) residue. J Med Chem 2010;53:4550–4

- Mollica A, Feliciani F, Stefanucci A, et al. N-(tert)-butyloxycarbonyl)-beta,beta-cyclopentyl-cysteine (acetamidomethyl)-methyl ester for synthesis of novel peptidomimetic derivatives. Protein Pept Lett 2010;17:925–9

- Karoyan P, Sagan S, Lequin O, et al. Targ Heter Sys 2005;8:216–73

- Zhang F, Klebansky B, Fine RM, et al. Molecular mechanism of the sweet taste enhancers. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2010;107:4752–7

- (a) Mollica A, Pinnen F, Azzurra S, Costante R. The evolution of peptide synthesis: from early days to small molecular machines. Curr Bioact Comp 2013;9:184–202. (b) Mollica A, Paglialunga Paradisi M, Torino D, et al. Hybrid α/β-peptides: For–Met–Leu–Phe–OMe analogues containing geminally disubstituted β2,2- and β3,3-amino acids at the central position. Amino Acids 2006;30:453–9

- Dörrich S, Falgner S, Schweeberg S, et al. Silicon-containing dipeptidic aspartame and neotame analogues. Organometallics 2012;31:5903–17

- Muto T, Tsuchiya D, Morikawa K, Jingami H. Structures of the extracellular regions of the group II/III metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2007;104:3759–64

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 2007;23:2947–8

- McWilliam H, Li W, Uludag M, et al. Analysis tool web services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res 2013;41:W597–600

- Shen MY, Sali A. Statistical potential for assessment and prediction of protein structures. Prot Sci 2006;15:2507–24

- Van Der Spoel D, Lindahl E, Hess B, et al. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J Comp Chem 2005;26:1701–18

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. {PROCHECK}: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst 1993;26:283–91

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 2010;31:455–61

- Mirzaie S, Fathi F, Hakhamaneshi MS, et al. Combined 3D-QSAR modeling and molecular docking study on multi-acting quinazoline derivatives as HER2 kinase inhibitors. EXCLI J 2013;12:130–43

- Schuttelkopf AW, van Aalten DM. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Cryst D, Biol Cryst 2004;60:1355–63

- Gasteiger J, Marsili M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electronegativity-a rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron 1980;36:3219–28

- Wang R, Lai L, Wang S. Further development and validation of empirical scoring functions for structure-based binding affinity prediction. J Comput-aided Mol Des 2002;16:11–26

- Bas DC, Rogers DM, Jensen JH. Very fast prediction and rationalization of pKa values for protein-ligand complexes. Proteins 2008;73:765–83

- Lemkul JA, Allen WJ, Bevan DR. Practical considerations for building GROMOS-compatible small-molecule topologies. J Chem Inf Mod 2010;50:2221–35

- Mirzaie S, Najafi K, Hakhamaneshi MS. Investigation for antimicrobial resistance-modulating activity of diethyl malate and 1-methyl malate against beta-lactamase class A from Bacillus licheniformis by molecular dynamics, in vitro and in vivo studies. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2015;33:1016–26

- Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, et al. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys 1984;81:3684–90

- Parrinello M, Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J Appl Phys 1981;52:7182–90

- Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J Chem Phys 1993;98:10089–92

- Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comput Chem 1997;18:1463–72

- Kumari R, Kumar R, Lynn A. g_mmpbsa – a GROMACS tool for high-throughput MM-PBSA calculations. J Chem Inf Model 2014;54:1951–62

- Mollica A, Feliciani F, Stefanucci A, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new active For–Met–Leu–Phe–OMe analogues containing para-substituted Phe residues. J Pept Sci 2012;18:418–26

- Kunishima N, Shimada Y, Tsuji Y, et al. Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature 2000;407:971–7

- Tsuchiya D, Kunishima N, Kamiya N, et al. Structural views of the ligand-binding cores of a metabotropic glutamate receptor complexed with an antagonist and both glutamate and Gd3+. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2002;99:2660–5

- Gundampati RK, Chikati R, Kumari M, et al. Protein–protein docking on molecular models of Aspergillus niger RNase and human actin: novel target for anticancer therapeutics. J Mol Mod 2012;18:653–62

- Cui M, Jiang P, Maillet E, et al. The heterodimeric sweet taste receptor has multiple potential ligand binding sites. Curr Pharm Des 2006;12:4591–600

- Assadi-Porter FM, Tonelli M, Maillet EL, et al. Interactions between the human sweet-sensing T1R2-T1R3 receptor and sweeteners detected by saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010;1798:82–6

- Acher FC, Selvam C, Pin JP, et al. A critical pocket close to the glutamate binding site of mGlu receptors opens new possibilities for agonist design. Neuropharmacology 2011;60:102–7

- Parenti MD, Rastelli G. Advances and applications of binding affinity prediction methods in drug discovery. Biotechnol Adv 2012;30:244–50

- Venken T, Krnavek D, Munch J, et al. An optimized MM/PBSA virtual screening approach applied to an HIV-1 gp41 fusion peptide inhibitor. Proteins 2011;79:3221–35

- Barakat KH, Jordheim LP, Perez-Pineiro R, et al. Virtual screening and biological evaluation of inhibitors targeting the XPA-ERCC1 interaction. PloS One 2012;7:e51329