| Abbreviations | ||

| ANOVA | = | Analysis of variance |

| AO | = | Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen |

| ASA | = | American Society of Anesthesiologists (physical status classification system) |

| CI | = | Confidence intervals |

| CS | = | Constant-Murley Shoulder Score |

| CT | = | Computerized tomography |

| DSSAK | = | Danish Society for Shoulder and Elbow Surgery |

| DSR | = | Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry |

| EQ-5D | = | EuroQol (standardized measure of health status) |

| HA | = | Hemiarthroplasty |

| NRS | = | Non-randomized studies |

| ORIF | = | Open reduction and internal fixation |

| OSS | = | Oxford Shoulder Score |

| OTA | = | Orthopaedic Trauma Association |

| RCT | = | Randomized clinical trial |

| RSA | = | Reverse shoulder arthroplasty |

| SD | = | Standard deviation |

| SECEC | = | Société Européenne de Chirurgie de l’Epaule et du Coude |

| SF-36 | = | Short Form-36 |

| 3D | = | Three dimensional |

Definitions

‘Complex fractures’ designates displaced four-part fractures or fracture-dislocations within the Neer classification and Type C fractures within the AO/OTA classification.

A ‘prospective, observational, comparative study’ is a study that prospectively collects data and compares outcome in patients treated with the intervention under study with patients treated with a control intervention.

A ‘retrospective, observational, comparative study’ is similarly defined as a study in which outcome is collected retrospectively, for example based on a clinical database or a registry.

A ‘case series’ designates a study of outcome in a series of patients treated with an intervention, but without comparison with patients receiving a control intervention.

Introduction

’Via sanationis, partim ad naturam attinet, quæ callo fracturam agglutinat; partim ad medicum qui impedimenta submovet, & ossa componit.’ Vidus Vidius (Citation1596) 2

Fractures of the proximal humerus are common injuries. They comprise about 4% of all fractures3, 4. The incidence is approximately 70 per 100,0005, 6 and it will probably increase due to the association with age and osteoporosis7-10. In women 80 years and older the incidence is third only to fractures of the proximal femur and the distal radius11. Women aged 60–79 years who had suffered a fracture of the proximal humerus have a residual lifetime risk of sustaining a hip fracture of 2.5 (1.3–3.6, 95% CI)12.

The management of fractures of the proximal humerus has challenged medical practitioners since the beginning of recorded medical history. Controversies on the principles for classification and management can be found in written sources from Greek and Roman Antiquity13. Changing approaches have appeared at all times, and there is still no consensus on the management of those injuries. The principles for pathoanatomical and pathophysiological understanding of proximal humeral fractures were laid down in the preradiographic era, especially in the 18th and 19th century14. I have been unable to identify any studies on the changing historical approaches to proximal humeral fractures.

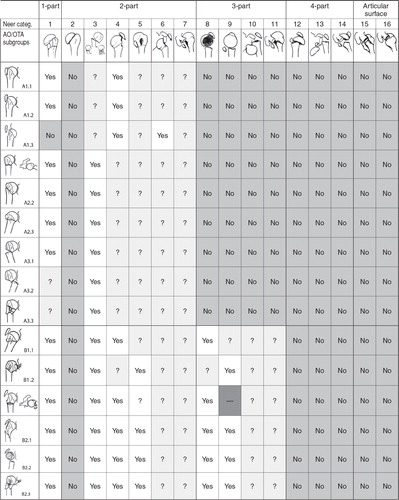

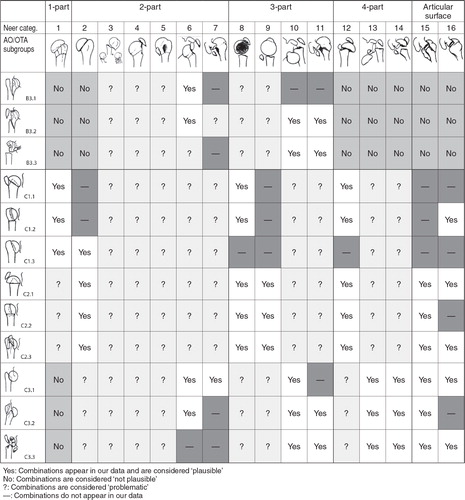

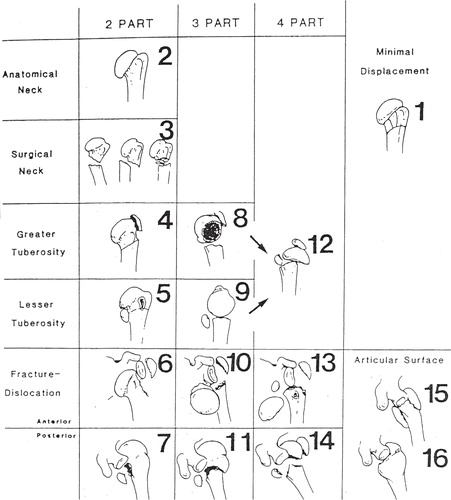

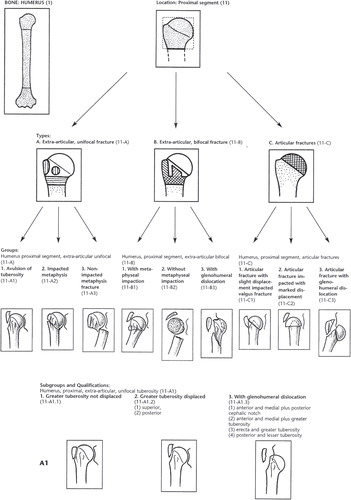

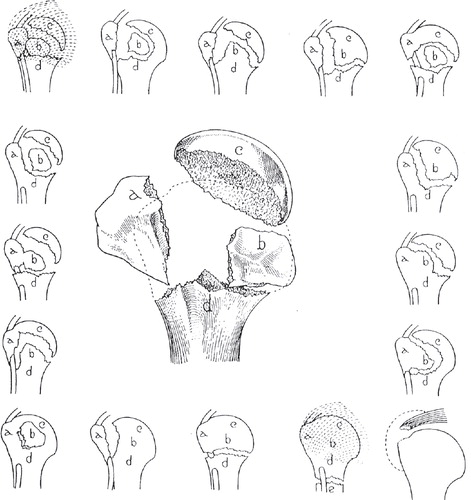

Fracture classifications are used to guide treatment, estimate prognosis, and predict the risk of complications. Ideally, a fracture classification should be clinically useful, categorization should be possible from preoperative images, and it should demonstrate observer agreement on an acceptable level. A fracture classification should further serve as a tool for reporting in the scientific literature, assist documentation in clinical databases, and enable pooling of data across studies. The most frequently used classification systems of proximal humeral fractures are the classifications proposed by Charles Neer (1917–2011) in 197015 (), revised in 197516 and 200217, and the AO/OTA classification proposed by CitationMaurice Müller et al. (1918–2009) in 199018 and revised in 2007 ()19.

Figure 1. The 16 categories of the Neer classification. A fracture is considered displaced if one or more of the four anatomical segments (greater tuberosity, lesser tuberosity, the humeral head, or the humeral shaft) are displaced more than 1 centimeter or angulated more than 45°. Modified from Neer (Citation1970) 15 with permission from JBJS Am, Rockwater Inc.

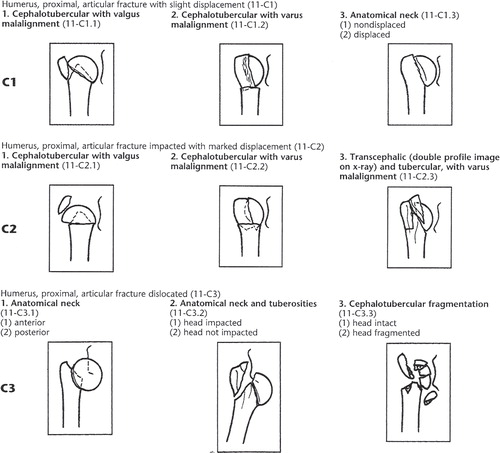

Figure 2. The AO/OTA classification consists of three types, nine groups, and 27 subgroups hierarchically organized according to prognosis. Type A fractures are unifocal and extraarticular, type B are bifocal and extraarticular while type C fractures are intraarticular. Reprinted from Marsh (Citation2007) 19 with permission from J Orthop Trauma, Copyright Clearance Center.

Within the last two decades several observer studies have reported low agreement among doctors classifying according to the Neer or the AO systems20-29 prompting a debate about the scientific and clinical merits of the two classification systems30-34. Lack of consistency in classification is one possible reason for the discrepancies in reported outcome after treatment of proximal humeral fractures. With no gold standard for fracture classification, observer studies may serve as an indirect evaluation of reliability and accuracy of classification systems. However, high levels of observer agreement do not necessarily mean high accuracy as observers can agree on a wrong diagnosis. Low levels of observer agreement preclude a high accuracy since observers, if they cannot agree with each other and themselves, they cannot all be right. The clinical implications of low observer agreement are unclear.

Treatment modalities for proximal humeral fractures are ranging from non-operative management to primary HA or RSA and numerous methods of ORIF. However, only few randomized trials have been conducted35-39 and systematic reviews have reported a lack of reliable evidence for clinical decision-making40-46. The natural course of complex fractures of the proximal humerus is widely unknown. There is a lack of larger size studies of non-surgical treatment and only few series with conflicting conclusions have been published39, 47-52. HA has been the treatment of choice in four-part fractures, head splitting fractures, and fracture-dislocations at most centers. Several systematic reviews have analyzed data from studies of three- and four-part fractures treated with primary HA, and they have concluded that there is no strong scientific evidence to support the effectiveness of early HA in proximal humeral fractures41, 42, 46, 53. Even the decision to operate on these patients is not supported by high level evidence.

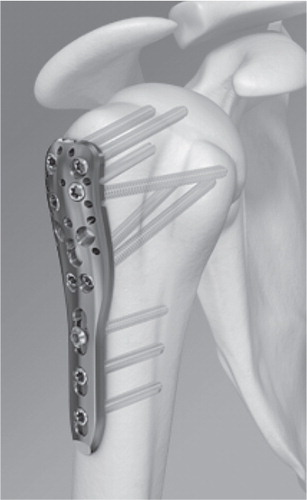

Within the last decade locking plate technology () has changed the approach to extremity fractures in elderly54-57. A recent randomized trial37 comparing outcome after locking plate osteosynthesis versus non-surgical management in 60 three-part fractures reported a non-significant improvement in functional outcome in the surgical group. Additional surgery was performed in 30 percent compared to non-surgical treated. Several authors of narrative reviews and clinical series have recommended fixation of displaced four-part fractures and AO/OTA type C fractures with locking plates58-66 and implant producers advocate them67-70. However, to my knowledge, no systematic review on the benefits and harms of this new technology in four-part fractures or in AO/OTA type C fractures has been published.

Figure 3. Locking plate for proximal humeral fractures (Philos). Reprinted with permission from Synthes.

In elderly patients with complex fractures and poor bone stock it may be impossible to obtain satisfactory anatomical fixation of the tuberosities to a HA. In such cases, primary insertion of RSA () has been suggested71-75. Pain relief and early mobilisation after RSA in acute fractures has been reported42 but only few long term results are available76. Long learning curves for RSA have been reported77, 78, revision surgery is challenging79, and the long term consequences of scapular notching are widely unknown. No systematic review studying outcome after RSA in acute fractures have been identified.

Aims of the thesis

The overall aim of the thesis is to establish an evidence basis for classification and treatment decisions in proximal humeral fractures. Secondary aims include:

to study historical approaches to proximal humeral fractures (Paper I–IV)

to study the agreement on Neer-classification among doctors at different levels of clinical experience (Paper V)

to study the effect of systematic training of doctors in the Neer classification (Paper VI)

to systematically review studies of observer agreement among doctors classifying according to the Neer classification (Paper VII)

to study the agreement on the diagnosis of four-part fractures (VIII)

to compare the agreement on classification with the agreement on treatment recommendations (Paper IX)

to study patterns of ‘translation’ between the Neer and the AO/OTA classification (PaperX)

to systematically review clinical studies assessing outcome after osteosynthesis with locking plates in four-part fractures or type C fractures (Paper XI–XII)

to systematically review clinical studies assessing outcome after reverse prosthesis in acute fractures (Paper XIII)

to design a protocol for future RCTs assessing outcome after surgical and non-surgical management of four-part fractures of the proximal humerus (Paper XIV)

Historical review

’These cases [fracture-dislocations of the proximal humerus] should teach the members of our profession to be kind, generous, and liberal towards each other; and not to impute to ignorance or inattention that which is the result of a generally-incurable accident.’ Sir Astley Cooper (Citation1839) 80

Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome (Paper I)

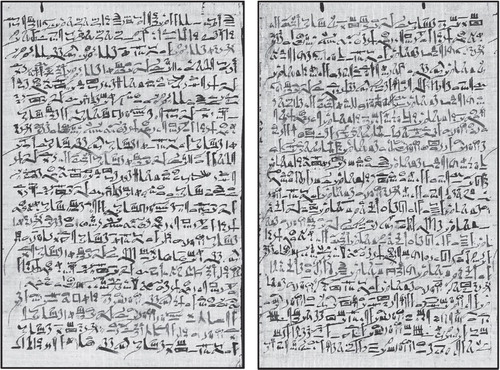

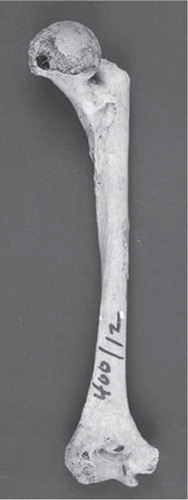

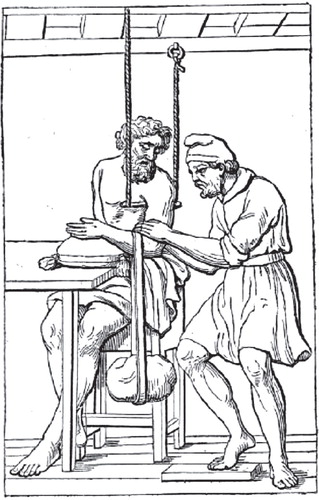

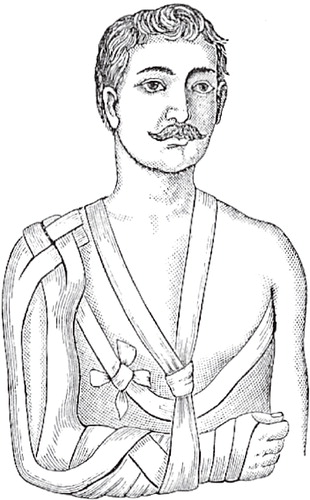

In the earliest known surgical text, Edwin Smith Papyrus 81, 82, three cases of humeral fractures are described (). Reduction by traction followed by bandaging with strips of cloth with alum, oil, and honey is described. The prognosis of closed injuries of the humerus is considered favorable. However, in compound fractures with bone penetrating the soft tissue and blood issuing from the wound the prognosis is considered hopeless. Well preserved healed fractures of the humerus have been excavated (), but the results after the described treatments have not been recorded as no humeral fractures with bandages in situ have been found. In the Hippocratic Corpus (circa 440–340 BC) the author of On Fractures 83, 84 distinguishes prognostically between proximal and distal fractures of the humerus. A fracture of the head of the humerus is considered milder than injuries near the elbow joint. A maneuver of reduction () is described. Bandages of linen soaked in cerate and oil are applied followed by splinting after a week. Healing is expected in forty days. In The Alexandrian School of Medicine (third century BC)85 fracture-dislocations of the proximal humerus are mentioned, and it is discussed whether the dislocation should be reduced before or after setting the fracture. In Celsus (25 BC to AD 50)86 humeral shaft fractures are distinguished from proximal and distal humeral fractures. Pathoanatomical patterns including transverse, oblique, and multi-fragmented fractures, their typical patterns of displacement, and the sensation of crepitus are described.

Figure 5. The Edwin Smith Papyrus (copied c. 1600 BC). Column XII and XIII including three cases on humeral fractures. Reprinted from Allen (Citation2005) 81 with permission from The New York Academy of Medicine Library.

Figure 6. Healed fracture of a left proximal humerus (posterior view). Young woman. First or middle part of New Kingdom (c. 1539–1075 BC). Reprinted with permission from Laboratory of Biological Anthropology, University of Copenhagen.

Figure 7. Reduction of a fractured humerus according to De Fracturis (c. 415 BC). Reprinted from É. Littré (Citation1841) 152.

From the fall of the Roman Empire to the late eighteenth century (Paper II)

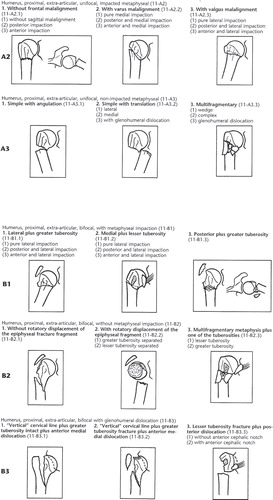

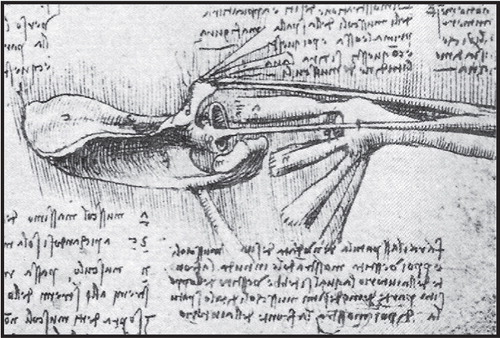

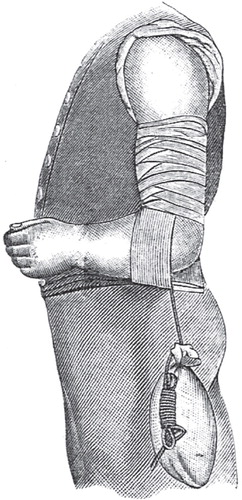

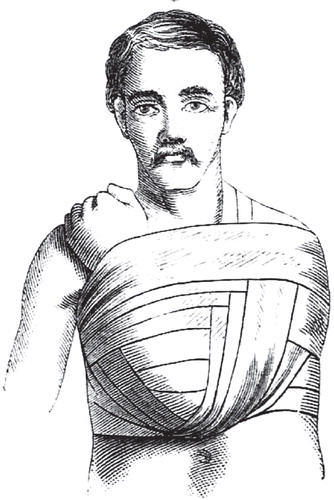

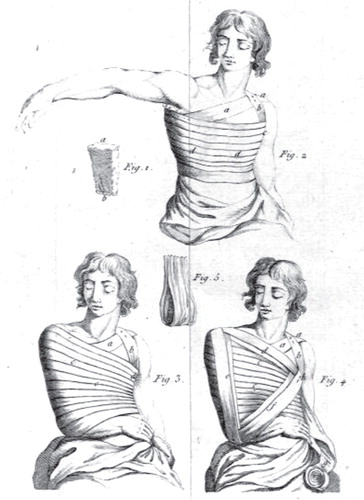

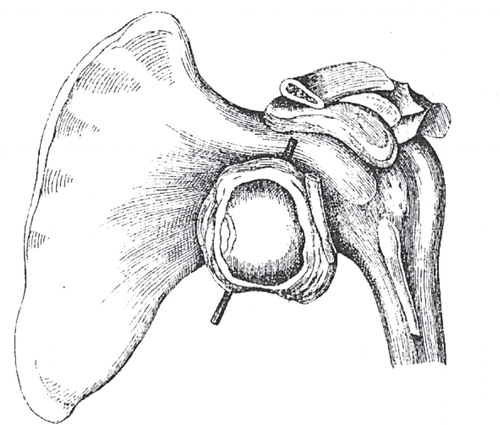

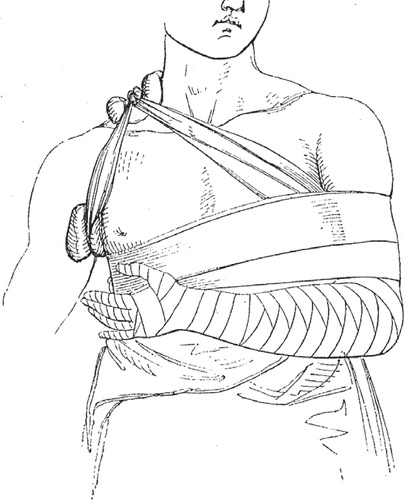

In Albucasis of Cordoba (936–1013)87 plasters of mill-dust and egg-white are applied after reduction. Provided no swelling or inflammation is present splints made from pine or palm tree are subsequently applied. Finally, the forearm is bandaged to the humerus, placing the hand open on the uninjured shoulder. Albucasis’ principle of bandaging can be found in the bandage later ascribed to Velpeau (1795–1867)88 (). In his anatomical drawings Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)89-91demonstrates a thorough knowledge of the biomechanical properties of the shoulder. In Figure 9 the humeral head is withdrawn from the glenoid cavity and viewed from above. This view enables a common presentation of the osseous structures, the four muscles of the rotator cuff, the insertions of both heads of the biceps, and the structures attached to the coracoid process (short head of biceps, coracobrachialis, and pectoralis minor). French surgeons in first half of eighteenth century conduct human anatomical studies to understand the pathoanatomical and pathophysiological basis of fracture displacement. Joseph Duverney (1648–1730)92 distinguishes four different ‘species’ of fractures of the proximal humerus: transverse fractures, oblique fractures, fractures with splinters, and fractures with bone shivered to pieces. He further describes the pathophysiological mechanism of the shortening seen in proximal humeral fractures. Pierre-Joseph Desault (1744–1795)93-95 characterizes fractures of the proximal humerus according to trauma mechanism, anatomical level, pathoanatomical pattern, the state of the surrounding soft parts, and displacement of fragments. Desault also mentions complicating factors in fractures including fracture-dislocations, compound fractures and fractures followed by infection. Based on considerations upon the muscles acting on the fractured parts, Desault rejects the Hippocratic mode of extension repeated in written sources for more than two millennia. He proposes a more gentle procedure of reduction by extension and counter-extension involving two assistants. The reduction is maintained by a three-layer bandage ().

Figure 8. Velpeau’s bandage. Reprinted from Bergmann and Bruns (Citation1901) 153.

Figure 10. Desault’s three-layer bandage recommended for immobilisation of fractures of the clavicle and the proximal humerus. The bandage was also used for immobilisation of glenohumeral dislocations. Reprinted from Desault (Citation1805) 95.

Nineteenth century sources (Paper III)

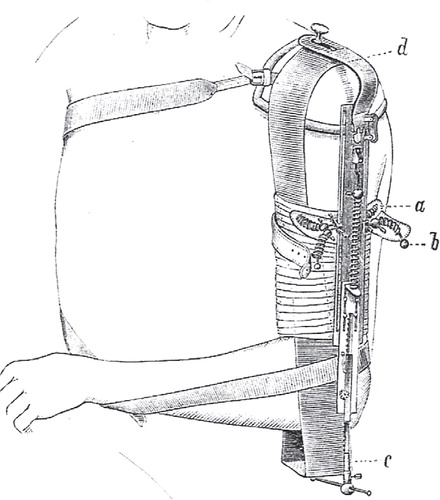

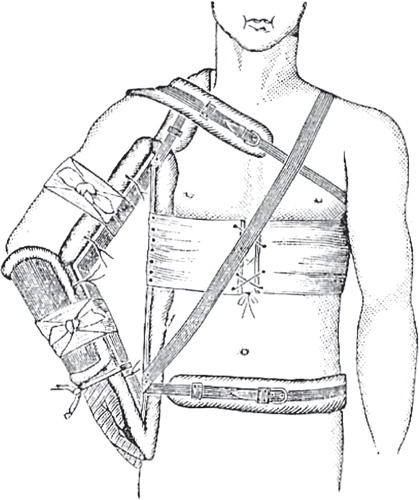

The difficulties of distinguishing displaced or impacted fractures of the proximal humerus from glenohumeral dislocations and fracture-dislocations are discussed by Sir Astley Cooper (1768–1841)96. He comments on the reduction of fracture-dislocations which he considers incurable. He states that the surgeon can do what he will, the head of the bone will probably remain in the axilla (), and the upper motions of the arm will be in a considerable degree lost97. Several early nineteenth century authors propose pathoanatomical classification systems for proximal humeral fractures, among others, Astley Cooper, Robert William Smith (1807–1873)98 and, Joseph-François Malgaigne (1806–1865)1, 99. In 1851, Johann Ludwig Wilhelm Thudichum (1829–1901)100 publishes a comprehensive classification based on the anatomic level of the fracture lines (). Numerous bandages for fractures of the proximal humerus are developed in the nineteenth century. Robert Liston’s (1794–1847) bandage allows for a permanent valgus pressure ()101. The bandage is extended to the forearm and hand to prevent soft tissue swelling. “Middledorpf’s triangle” (1824–1868) ()102 fixes the upper arm in abduction. Hamilton’s (1813–1886) adhesive plasterbandage applies a permanent traction ()103, and Bardenheuer’s (1839–1913) extension apparatus ()104 allows for differentiated traction during the immobilisation period. After Antonius Mathijsen (1805–1878) introduced the hard setting plaster of Paris bandage in 1852105-107, plaster bandages for fractures of the proximal humerus are developed. Hennequin’s (1836–1910) plaster bandage ()102 uses the principle of the later hanging cast.

Table I. Classification of fractures of the proximal humerus. Translated and modified from Thudichum (Citation1851)

Figure 11. Unreduced fracture-dislocation of the proximal humerus. Reprinted from Thudichum (Citation1851) 100.

Figure 12. Liston’s bandage. Reprinted from Liston (Citation1838) 101.

Figure 13. Middledorpf’s triangle. Reprinted from CitationStimson (1899) 102.

Early twentieth century sources (Paper IV)

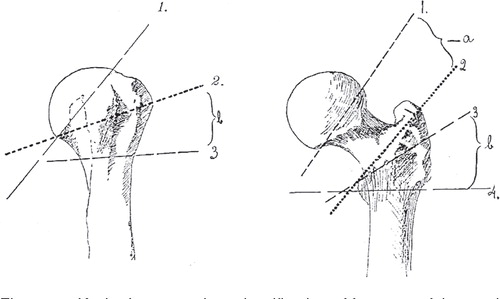

Emil Theodor Kocher (1841–1917)108 proposes the last comprehensive pre-radiological classification system for fractures of the proximal humerus in 1896, the same year as Roentgen’s (1845–1923) important work on ‘a new kind of rays’109. Kocher’s classification is pathoanatomically based and developed in analogy to his classification of fractures of the proximal femur (). To capture the pathoanatomy and pathophysiolgy of proximal humeral fractures Ernest Amory Codman (1869–1940)110 suggests studying the involvement of four distinct anatomical segments along the lines of the epiphyseal union: the greater tuberosity, the lesser tuberosity, the humeral head, and the humeral shaft (). The four-segment approach is radiographically defined, but takes into account the muscular forces of the rotator cuff acting on the four segments. Codman’s approach profoundly influenced later classifications. Charles Neer first refers to Codman’s classification in 1953111. In his classification from 197015 Neer integrates fracture anatomy, biomechanics, and the notion of displacement. It is built upon knowledge of the effect of muscles attaching to free segments, rotator cuff integrity, the effect of the vascular supply to the humeral head, and the condition of the articular surface. Neer’s extension of Codman’s four- segment approach was a breakthrough in classification of proximal humeral fractures.

Figure 15. Bardenheuer’s extension apparatus. Reprinted from CitationHoffa (1888) 104.

Figure 17. Kocher’s approach to classification of fractures of the proximal humerus and the proximal femur. Reprinted from Kocher (Citation1896) 108.

Figure 18. The four anatomical segments of the proximal humerus. Reprinted from Codman (Citation1934) 110 with permission from Krieger Publishing Company.

Classification

‘Unfortunately, all these classification systems have failed to show that a fracture belonging to a particular group has a distinctly different prognosis, requires a different treatment, or has a different outcome.’ Christian Gerber (2005)112

The conduct of randomized clinical trials usually involves multiple centers for gaining sufficient statistical power, especially in complex fracture patterns. The conduct and interpretation of multi-centre trials are facilitated by a rigorous approach to classification. It remains difficult to interpret and compare outcome, and obtain consensus on treatment recommendations, when clear definitions and a common ‘fracture language’ is lacking.

Agreement on unselected radiographs in a clinical setting: an observer study (Paper V)

Previous observer studies have used a limited number of observers and cases, and the agreement on subgroups of certain fracture patterns and the importance of clinical experience of observers has been imprecisely estimated. I aimed to study inter-observer agreement within a large group of orthopaedic doctors using the Neer classification. The secondary aim was to study the inter-observer agreement between doctors at three levels of clinical experience. We conducted an observer study based on an unselected, consecutive series of proximal humeral fractures (n=42) including as observers the full medical staff (n=24) at the department of orthopaedic surgery in a Danish university hospital. The observers independently classified all sets of radiographs according to the 16 category Neer classification. To mimic the clinical situation no selection according to quality of images was allowed, and the observers were not informed about the study prior to the classification session. Mean kappa value for inter-observer agreement was 0.27 (95% CI 0.26–0.28) with no clinically significant difference between orthopaedic residents, fellows, and specialists (). Mean kappa values for inter-observer agreement on displaced versus non-displaced fractures were 0.41 (95% CI 0.39–0.43) overall, and 0.50 (95% CI 0.45–0.56) within the specialist group. I concluded that all kappa values were dissatisfying from a clinical perspective, and means of improving observer agreement should be studied.

Table II. Mean kappa values (95% CI) for agreement on the Neer classification at three levels of clinical experience

The effect of training of doctors: a randomised clinical trial (Paper VI)

I studied the effect of systematic training of doctors in the Neer classification. Fourteen doctors independently classified 42 unselected sets of radiographs (same images as in Paper V) according to the 16 category Neer classification. Subsequently, they were randomly allocated to a training group or a control group. The training group was taught the Neer classification for 45 minutes based on material from Neer’s original article15. Two weeks later, the training group received a second teaching session of 45 minutes, before all participating doctors were presented with the same sets of radiographs, but in a different order. The mean difference in kappa between the training and control groups was 0.30 (95% CI 0.10–0.50, p=0.006) (). In the training group the mean kappa value for inter-observer agreement improved from 0.27 (95% CI 0.24-–0.31) to 0.62 (95% CI 0.57–0.67) (p = 0.006). The improvement was particularly notable for specialists in whom kappa increased from 0.30 (95% CI 0.23–0.37) to 0.79 (95% CI 0.70–0.88). The increase in agreement after teaching in the training group was equally distributed among all pairs of observers, while agreement among all pairs of observers in the control group remained distributed around baseline kappa. I concluded that when the Neer classification is used by untrained doctors it is too unreliable for clinical practice and research. Formal training in the Neer classification seems to be a prerequisite for its use in clinical practice and research.

Table III. Mean (95% CI) kappa values for classification according to Neer

A systematic review of observer studies (Paper VII)

A systematic review of observer studies among doctors classifying proximal humeral fractures according to the Neer classification was conducted. The primary aim was to review studies of inter- and intra-observer agreement among doctors using the Neer classification. The secondary aim was to study factors that potentially could influence the level of agreement. I included observational studies in which doctors were asked to independently classify a series of proximal humeral fractures according to the Neer classification, and randomized trials of interventions that could possibly influence the level of agreement. A predefined quality assessment of the individual observational studies and randomized trials was conducted. Based on eleven observational studies and one randomized trial I found that doctors disagree substantially when classifying according to the Neer classification. The overall mean kappa-values for inter-observer agreement in studies reporting unweighted kappa-values ranged from 0.17 to 0.52 (). In the studies reporting weighted kappa-values for inter-observer agreement mean kappa-values ranged from 0.30 to 0.40. The five studies that reported intra-observer agreement as kappa values generally found it higher than the inter-observer agreement ranging from 0.34 to 0.72. No clear improvement by adding CT or 3D CT scans to plain radiographs was found. No improvement was found by simplification of the classification to 2, 5, 6, 13 or 15 categories. Only one study reported kappa values for inter-observer agreement exceeding 0.60. This value was obtained in the randomized study testing the effect of standardized training of orthopaedic doctors (Paper VI).

Table IV. Inter-observer agreement in 12 observer-studies (mean kappa and/or range of kappa)

Agreement on the diagnosis of displaced four-part fractures: a review of observer studies (Paper VIII)

Displaced four-part fractures are challenging to diagnose, classify, and manage. These severe injuries have been reported to comprise 2–10% of all proximal humeral fractures113-115. I aimed to quantify observer agreement on classification of displaced four-part fractures. I extracted published and unpublished data on four-part fractures and calculated mean kappa-values for inter- and intra-observer agreement. Five observer-studies were included. Mean kappa-values for inter-observer agreement ranged from 0.16 to 0.48. In six out of eight classification sessions the observers agreed less on displaced four-part fractures than on the overall Neer classification. Specialists agreed slightly more than fellows and residents. Advanced imaging modalities (CT and 3D CT) seemed to contribute more to agreement on classification of displaced four-part patterns than in less complex patterns. In a study involving training of observers (Study VI) the ‘prevalence’ of displaced four- part fractures decreased from 10 to 2% after training at all levels of clinical experience. Mean kappa-values for intra-observer agreement on four-part fractures ranged from 0.26 to 0.55 as compared with 0.51 to 0.56 for overall agreement on the Neer classification. I concluded that observers agree less on four-part fractures than on the Neer classification in general, and low observer agreement may challenge the clinical approach to displaced four-part fractures and pose a problem for the interpretation and generalization of results from clinical trials.

Agreement on treatment recommendations among shoulder surgeons: an observer study (Paper IX)

The clinical implication of low observer agreement among orthopaedic surgeons classifying proximal humeral fractures is unclear. I aimed to compare the agreement on Neer classification with the agreement on treatment recommendations. We conducted a multi-centre observer-study among five experienced shoulder surgeons assessing a large, consecutive series of unselected radiographs (n=193). The observers independently assessed and classified all sets of radiographs according to the Neer classification on two occasions three months apart. Subsequently, the observers were asked to recommend one of three treatment modalities for each case: non-surgical treatment, locking plate osteosynthesis, or primary hemiarthroplasty. I recorded if changes in classification categories were accompanied by changes in treatment recommendation. At both classification rounds mean kappa-values for inter-observer agreement on treatment recommendations (0.48 and 0.52) were significantly higher than the agreement on Neer classification (0.33 and 0.36) (p<0.001 at both rounds; ). The highest mean kappa-values were found for inter-observer agreement on non-surgical treatment (0.59 and 0.55). In 36% (345 out of 965) of observations an observer changed Neer category between first and second classification round. However, in only 34% of these cases (116 out of 345) the observers changed their treatment recommendation. I concluded that the low observer agreement on the Neer classification reported in numerous observer studies may have less clinical importance than previously assumed.

Table V. Mean kappa-values (95% CI) for interobserver agreement between five shoulder surgeons

Translation between the Neer classification and the AO/OTA classification: Do we need to be bilingual to interpret the scientific literature? (Paper X)

The reporting of clinical trials of proximal humeral fractures is hampered by the use of two different fracture classification systems; the Neer classification () and the AO/OTA classification (). I approached the problem empirically by ‘mapping’ patterns of translation between the two classification systems as they appear in the scientific literature. First, large clinical series containing data from both classification systems were systematically searched and analyzed. Second, discrepancies and problematic translations were qualitatively analyzed. Third, a table () for cross-checking of fracture coding for reporting and interpretation of data in the scientific literature was proposed. Primary data from 2530 cases from seven studies providing primary data from both classification systems were analyzed. Thirty-five percent (151 out of 432) of the combinations were considered ‘not plausible’ and thirty-four percent (149 out of 432) were considered ‘problematic’. Problematic combinations were discussed and a tentative table for cross- checking of fracture coding was proposed (). The assumption that AO/OTA type A fractures are 2- part fractures, type B are three-part fractures, and type C are four-part fractures58, 116, 117 was not supported by our data. Intraarticular fractures (AO/OTA Type C) can appear as one-, two-, three-, or four-part fractures within the Neer classification. Thus, clinical important information is lost within both classification systems. Most importantly, the varus/valgus distinction is not found in the Neer classification and a clear definition of displacement is lacking in the AO/OTA classification.

Management

’There is one very striking thing about fractures of the humerus, and that is that most cases eventually recover pretty good use of their shoulders in spite of any kind of treatment.’ Ernest Amory Codman (Citation1934) 110

Benefits and harms of locking plate osteosynthesis in displaced four-part fractures: a systematic review (Paper XI)

A systematic review of clinical studies reporting outcome after osteosynthesis with locking plates in displaced four-part fractures was conducted. Clinical studies, randomized trials, comparative studies (prospective or retrospective), and case series were included. Fourteen studies representing 374 four-part fractures were identified. There were no randomized trials, one prospective observational comparative study, three retrospective, observational, comparative studies, and ten case series. Unclear reporting in all 14 studies hampered the assessment, and small studies with a high risk of bias precluded reliable estimates of functional outcome. Mean non-adjusted CS for four-part fractures ranged from 57 to 76. High rates of complications (16% to 64%) and re-operations (11% to 27%) were reported. The major harm was primary and secondary screw penetration. I concluded that the empirical foundation for locking plates in displaced four-part fractures of the proximal humerus is weak with a considerable risk of bias.

Benefits and harms of locking plate osteosynthesis in intra-articular fractures (AO/OTA Type C): a systematic review (Paper XII)

A systematic review of clinical studies assessing outcome after osteosynthesis with locking plates in intraarticular fractures (AO/OTA Type C) was conducted. The methodological approach was similar to Paper XI except for the search for AO/OTA Type C fractures. Twelve studies representing 282 Type C fractures were included. The number of included Type C fractures per study ranged from 10 to 54. No randomized trials, one prospective, observational, comparative study, one retrospective, observational, comparative study, and nine case series (six prospective and three retrospective) were identified. Mean non-adjusted CS ranged from 53 to 75. The most commonly reported complications were avascular necrosis (range 4–33%), screw perforations (range 5–20%), loss of fixation (range 3–16%), impingement (range 7–11%) and, infections (range 4–19%). Reoperation rate ranged from 6 to 44%. The reporting of the included studies was too unclear for a valid assessment of risk of bias or meaningful estimates of functional outcome. In seven studies it was not possible to extract data on complications for Type C fractures separately. I concluded that inferior study designs and unclear reporting preclude safe treatment recommendations.

Reverse shoulder arthroplasty in acute fractures of the proximal humerus: a systematic review (Paper XIII)

In elderly patients with poor bone stock and complex fracture patterns it may be impossible to obtain satisfactory anatomical fixation and healing of the tuberosities to a HA. In such cases primary insertion of RSA has been suggested. In displaced four-part fractures and fracture- dislocations some forward elevation and abduction can be obtained even if the tuberosities do not heal. I systematically reviewed clinical studies reporting outcome after RSA in acute fractures of the proximal humerus. I included 18 studies representing 430 reverse prostheses in acute fractures. Non-adjusted CS for RSA in acute fractures ranged from 39 to 68. Three studies compared CS for RSA with a historical control of HA. Outcome was comparable to previous reviews of HA in four- part fractures. Reported complications included infection, hematoma, instability, dislocation, loss of rotation, neurological injury, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, intraoperative fractures, acromial fractures, periprosthetic fractures, and baseplate failure. Radiological scapular notching after reverse prostheses in acute fractures ranged from 3 to 97%. The clinical implications of scapular notching are debated, but studies with long term follow up report a decrease of functional outcome after five years118, 119.

Protocol for a multi-centre randomized clinical trial (Paper XIV)

Several surgical techniques have been suggested in displaced four-part fractures including transcutaneus reduction, external fixation, HA, or ORIF with Kirschner wiring, tension-band wiring, transosseous suturing, plate fixation, intramedullary rod fixation, screw fixation, or, most recently, locking plates. I compare the effect of ORIF with locking plates with non-surgical management in displaced four-part fractures in elderly. I also compare the effect of primary HA with both ORIF and non-surgical management. A randomized, multi-centre, clinical trial is conducted. After obtaining informed consent patients are randomly allocated to three groups of equal size: 1) non-surgical management (physiotherapy and self-training), 2) ORIF with locking plate followed by physiotherapy and self-training, or 3) primary modular HA followed by physiotherapy and self-training. Assessment of clinical outcome is performed after 12 months by the responsible surgeon and a blinded doctor not otherwise involved in the study. Clinical outcome is evaluated using CS120-122, OSS123, 124, and SF-36125, 126. The primary outcomes are blinded CS total score (0–100 points) and CS pain subscale score (0–15 points) at 12 months. The primary data analysis of effect are two analyses of variance based on the blinded overall CS, and the blinded CS pain subscale score, measured at 12 months. If one or both of the ANOVA analyses are statistically significant, a pair-wise testing based on t-tests is subsequently performed. Inclusion continues (January 2013).

Discussion

History

Historical reviews are subject to limitations. First, it may be doubted whether the written sources accurately represent the actual historical period. It is not known whether the written sources reflect common practice or were accessible to the learned elite only. For example, nineteenth-century textbooks by hospital trained surgeons may not reflect the actual treatment of the vast majority of injuries. Until the early twentieth century manipulation and splinting were mainly practiced by illiterate bonesetters. To the extent that we only have written sources left to posterity, we cannot safely draw conclusions regarding widespread treatment of proximal humeral fractures. But the written sources document that the procedures were considered. Many procedures were undoubtedly performed by various sorts of practitioners that were either never described or the descriptions were lost. It cannot be ruled out that some of these approaches were beneficial.

Second, pre-radiographic diagnostics relied on surface anatomy, pain localization, crepitus, and impaired function. The exact diagnosis and localization of injuries of the shoulder and upper arm remains unclear in preradiographic sources. Interpretations into modern scientific terms like “proximal fracture,” “shaft fracture,” “glenohumeral dislocation,” or “fracture-dislocation” should be made with caution. Dysfigurations of the shoulder and upper arm are often compatible with several pathologic conditions in the region, and some authors might well have classified a variety of conditions with an altered surface anatomy of the shoulder as “fractures”. However, the proposed management of fractures of the clavicle, acromioclavicular dislocations, glenohumeral dislocations, and fractures of the proximal humerus were often identical, even though the surgical texts treat them separately.

Third, not until the early eighteenth century fractures of the proximal humerus were clearly distinguished from humeral shaft fractures and a differentiated management, in a modern sense, could be provided. However, a thorough pathoanatomical understanding of fractures of the proximal humerus was not developed until the late eighteenth century when specimens of healed fractures were collected from autopsies and described systematically. The “true” diagnosis of a described injury remains unknown unless a pathologic specimen was obtained from autopsy and saved for posterity. Most specimens were obtained many years after the injury and, therefore, mainly healed lesions were seen, leaving studies of acute injuries to a few fatal cases.

Classification

Kappa statistics and its limitations

The studies reporting observer agreement are using kappa statistics. Kappa, as defined by Landis and Koch127, is the most commonly used measure of agreement for categorical data. However, several limitations of kappa statistics should be mentioned.

First, kappa values cannot be compared between studies with different marginal distribution of classified items (i.e. Neer categories) as the value of kappa depends on the marginal distribution of the categories128. Kappa decreases given fixed overall agreement rates with very high or very low prevalence of the categories, and a lower kappa-value can be expected if an uncommon category is studied in an unselected population129. This precludes a prudent pooling of kappa-values between studies. For example, in a specialized shoulder unit a higher prevalence of complex proximal humeral fractures are expected than in a general trauma unit. This may explain the low kappa-values reported in studies including unselected cases from a general orthopaedic population with a low prevalence of complex fractures. In his classical article from 1970 Charles Neer reported a proportion of non-displaced fractures of 85%15. Later epidemiological studies have reported a proportion of non-displaced fractures of 49%113 and 36%115, compared to 33% and 29% in my studies. Different age distributions may also affect the distribution of categories. The mean age in Neer’s study was 56 years, 66 years in Court-Brown’s study, 65 in Tamai’s study, and 67 in my study.

Second, kappa does not take into account the ‘prognostic distance’ between the categories. For example, the ‘prognostic distance’ between a non-displaced fracture (Neer category 1) and a displaced fracture of the anatomical neck (category 2) is greater than the ‘prognostic distance between a displaced surgical neck fracture (category 3) and a displaced fracture of the greater tuberosity (category 4). Assigning weights to kappa may address such differences, but previous studies using weighted kappa values have not reported the weighting factors used.

Third, a challenge to observer studies is the qualitative interpretation of chance- corrected agreement rates130. There is no commonly accepted threshold for when a kappa-value becomes incompatible with high quality clinical care. I have adopted the interpretation by Landis and Koch127, but other interpretations can be found in the literature131.

Fourth, Kappa depends on the number of observers132. If the number of observers increases standard error decreases and kappa stabilizes among a mean value suggesting that a certain minimum of observers is required. I have been unable to identify any formulae for calculation of the number of observers and cases needed in observer studies. I decided to follow Gjorup in recommending a number of cases no less than forty129.

Assessment of methodological quality of observer studies

A challenge to reviews of observer studies is to assess the methodological quality of the included oberver studies. Recently, we have been published130 guidelines for reporting of observer studies, but to my knowledge, no empirical studies have identified an association between aspects of methodological quality in observer studies and bias. I assumed that the risk of bias was lower when nine pre-defined criteria were present. However, I found no association between high methodological quality and the level of agreement regardless of explorative sensitivity analyses where I varied the criteria for a high quality study.

Perception and image interpretation

Agreement of fracture classifications may be limited by raters’ ability to agree on basic radiographic assessments. In the evaluation of a fracture radiograph, certain basic assessments appear to be easier for observers to agree on than others133. Therefore, observer agreement will depend not only on the number of groups in the classification, but also on the type of assessments to differentiate between the groups. At least two phases in the classification process can be distinguished134, 135: a) an initial interpretation of radiographs to produce a mental image of a fracture in three dimensions, and b) a matching of the three dimensional image to the system of classification. In my data, it is not clear at which stage the agreement is lost.

Conceptions of displacement

I found a higher proportion of displaced four-part fractures than previously reported (17% and 18% compared to 2–10% reported elsewhere)113-115. The difference may be ascribed to different conceptions of displacement. In three- and four-part fractures it is not clear whether all involved segments should be displaced according to Neer’s definition. Different approaches among the individual observers in my study may explain the differences in proportion of four-part fractures (range 8% to 35%) and the relatively low inter-observer agreement on these fractures, mean kappa 0.39 (95% CI 0.28–0.49) and 0.41(95% CI 0.30–0.51). Differences in definitions may lead to inconsistencies in the interpretation of scientific data and in the conduct of clinical studies and systematic reviews.

Patient characteristics and observer agreement

It can be questioned to what extent observer studies reflect actual clinical agreement. In a clinical setting the observers usually have extensive knowledge about the patient’s age, functional level, co-morbidity, findings from physical examination, bone quality, type of trauma, as well as access to expert colleagues for discussion. Thus, the reported kappa-values for agreement, based on imaging material only, may underestimate the agreement on diagnostic and therapeutic decisions in clinical settings. However, several authors have reported an underestimated severity of fracture patterns when preoperative classification was compared to intraoperative assessment136, 137.

No evidence-based treatment recommendations based on patients’ age are available. For example, it is not clear whether osteosynthesis with locking plate is an option in the very elderly, or whether HA or RSA is an option in younger patients. Post hoc I observed an increase in kappa-value from 0.38 to 0.53 (p = 0.012) in inter-observer agreement on the use of locking plates after adding information on the patients’ age (Study IX). An age- sensitive decision on locking plate osteosynthesis may reflect an assumption on an upper age limit for this treatment. However, in the remaining categories only a slight and non-significant increase in mean kappa-values for inter-observer agreement on classification and treatment were found after adding information on the patients’ age.

Management

I planned to conduct a systematic review of outcome after locking plate osteosynthesis in displaced four-part fractures and AO/OTA type C fractures. However, I realized that partial incommensurability between the two classification systems made my task difficult. For example, AO/OTA type C fractures can appear as one-, two-, three-, and four-part fractures within the Neer classification. The classical four-part fracture (Neer category 12) does not appear in the AO/OTA system, and valgus-impacted fracture patterns (AO/OTA sub-group A2.3, B1.1, C1.1, and C2.1) can appear in the Neer classification as one-, two-, three-, and four-part fractures. Therefore, I decided to conduct two separate systematic reviews.

Locking plates in displaced four-part fractures

The observational studies and case series reveal that the use of locking screws in rigid plates has lead to a new entity of complications in the treatment of proximal humeral fractures. The major complication is screw penetration. Primary (intra-operative) screw penetration of the humeral head is usually caused by poor surgical technique. Secondary screw penetration or screw cut-out is related to the rigidity of the locking plate. Paradoxically, cut-out is often seen in comminuted fractures and poor bone quality for which conditions locking plates are especially recommended. The empirical foundation for the value of locking plates in displaced four-part fractures is weak with a considerable risk of bias. This precluded reliable estimates of functional outcome but I did note high rates of complications and re-operations. The balance between benefits and harms is difficult to establish without further studies with a lower risk of bias.

Locking plates in type C fractures

The reporting of the included studies was too unclear for a valid assessment of risk of bias or a meaningful extrapolation of functional outcome after locking plate osteosynthesis in type C fractures. Insufficient study designs and unclear reporting preclude safe treatment recommendations. Complication and reoperation rates were unexpected high and no treatment recommendations can be given based on the studies included. In particular, reporting of mean CS for AO/OTA groups and sub-groups was problematic. In studies with one or two patients in a group the reporting of a mean value of CS is hardly meaningful. For example, one study138 reported an unexpected high mean CS of 78 for C3 fractures, based on only two patients. A calculation of an overall mean CS for all type C fractures is not clinically meaningful and a more detailed analysis presupposes access to individual patient data.

Adjustment for age

The external validity of the included studies can be questioned. The relatively low mean age in the included studies may indicate an unconscious or unreported upper limit of age for use of locking plates. If that is the case the reported outcomes cannot be used as a basis for clinical decision making in the elderly. If some elderly patients with Type C fractures have not been offered locking plate osteosynthesis a selection bias may be present. If non-surgical treatment is reserved for selected patients with a high intraoperative risk or limited functional demands the reported outcome may be underestimated in clinical series. The mean age was less than 60 years in three studies and between 60 and 70 years in the remaining studies. A mean age of 57 years was reported in the only prospective cohort study with parallel control139. A higher CS is expected in younger patients evaluated by non-adjusted CS because of the weight of strength and range of motion. As non-adjusted CS decreases in the elderly the positive effect of interventions in this group is likely to be underestimated. I recommend that future clinical trials comply with the age- and sex-adjusted score proposed by Constant et al.120, 122.

Reverse prosthesis in acute fractures

The reverse prosthesis was originally developed for cases when reconstruction of the tuberosities was impossible. However, reconstruction of the tuberosities seems to improve stability, and good functional outcome has been reported in cases where tuberosity fixation in reverse prostheses was performed. Fixation of the greater tuberosity seems essential for restoring external rotation after complex fractures. Sirveaux et al.140 reported a mean CS of 57 if the greater tuberosity was healed compared to 41 if the greater tuberosity was not healed. Emily et al.141 reported a mean adjusted CS of 45 in patients with no external rotation compared to 98 in patients with at least 10 degrees of external rotation. It is, however, not clear why a RSA should be preferred to a HA if tuberosity fixation is possible. The cost-effectiveness of RSA compared to HA in acute fractures with tuberosity reinsertion remains an open question.

Recent developments

The advent of locking plate technology has led to an increased interest in ORIF in patients with poor bone stock. However, the high complication rates in locking plate osteosynthesis suggests that non-operative treatment should be considered, even in patients with three- and four-part fractures. By the introduction of locking plates in three- and four-part fractures the indications of primary HA may have changed. Functional outcome can be expected to decrease if HA is used predominantly in the complicated fractures or in the most fragile patients. Thus, selection bias may be a concern. Comorbidity can confound the decision to operate. Recent reports from DSR142 have found a low revision rate in HA for fractures despite poor functional outcome suggesting that surgeons hesitate to revise these patients.

Is evidence from non-randomized studies better than no evidence?

Several methodological concerns when reviewing NRS should be mentioned143, 144. I have chosen a ‘best evidence approach’, but it may be objected that NRS have a restricted place in the scientific literature because of multiple possible biases. There is a lack of commonly accepted instruments for assessment of methodological quality in NRS. I decided to report functional outcome of the individual studies despite a high risk of bias, but I did not find it meaningful to report mean or median values for outcome between studies. I did report complications, failures, and reoperations. As the majority of NRS included favour the new surgical interventions reported, I find it unlikely that harms should be overestimated. However, the size and direction of bias in NRS compared with RCTs are difficult to predict145, 146. Other reasons for including NRS are the generation of new hyphoteses, and estimating SD for future sample size calculations.

Unanswered questions and future research

Challenges for future clinical research include partial incommensurability and low reliability of classification systems, a growing population of fragile elderly with substantial comorbidity and poor bone stock, and a tenacious tradition in orthopaedics for publishing retrospective case series. Focused observer studies could analyze sources of disagreement, for example whether disagreement occurs in the primary identification of fracture fragments or in other phases of the radiographic or clinical assessment. Additional randomized trials could seek to identify which training methods are the most effective. Prospective studies on the agreement on treatment recommendations among shoulder surgeons assessing all data on the patients could be useful. Two systematic reviews are in progress: a study of the benefits and harms of primary HA in four-part fractures, and a study of the benefits and harms of non-surgical management of four-part fractures. Inclusion of patients in our randomized trial (Paper XIV) continues. A multi-centre randomized clinical trial on outcome after primary RSA in displaced four-part fractures and head-split fractures is planned. Further, a prospective study of outcome after revision with RSA in failed HA after fractures is planned. Finally, registry studies of changes in the incidence of HA in fractures obtained from DSR compared with the incidence of ORIF obtained from The Danish National Patient Registry are planned.

Conclusions

The diagnosis and management of proximal humeral fractures have challenged medical practitioners at all times. The pathoanatomical approach considered valid today was developed more than a century before the radiographic era. Changing historical conceptions and clinical approaches to shoulder injuries have been identified and analyzed.

Consistently low kappa-values for interobserver agreement on the Neer classification and the AO/OTA classification were found. No clinically significant differences in observer agreement were found at different levels of clinical experience, by reducing the number of categories, or by adding high quality radiographs, CT or 3D CT scans. However, interobserver agreement on the Neer classification improved significantly after systematic training. A lower agreement on four-part fractures than on the Neer classification in general was found. A significantly higher agreement on treatment recommendation than on Neer classification was found among experienced shoulder surgeons, and low agreement on classification may have less clinical importance than previously assumed. The AO/OTA- and the Neer-classifications are partly incommensurable. The varus/valgus distinction is not found in the Neer classification and a clear definition of displacement is lacking in the AO/OTA classification. I recommend scholars to use both classification systems and check the plausibility of the chosen combination. However, classification remains a challenge for the conduct, reporting, and interpretation of clinical trials.

Unexpected high rates of complications and reoperations after locking plate osteosynthesis in displaced four-part fractures and type C fractures were found. Poor design and unclear reporting precluded reliable outcome estimates. In acute fractures functional outcome after RSA was comparable to HA in displaced four-part fractures, but complication rates were high. The long term consequences of scapular notching are not known. The evidence for the benefits of surgery in complex fractures of the proximal humerus is weak. Results from ongoing RCTs are expected147-151. Until higher quality evidence is available a routinely use of RSA, locking plates or reverse prostheses in displaced four-part fractures or AO/OTA type C fractures cannot be recommended outside clinical protocols.

Summary

Fractures of the proximal humerus have been diagnosed and managed since the earliest known surgical texts. For more than four millennia the preferred treatment was forceful traction, closed reduction, and immobilization with linen soaked in combinations of oil, honey, alum, wine, or cerate. The bandages were further supported by splints made of wood or coarse grass. Healing was expected in forty days. Different fracture patterns have been discussed and classified since Ancient Greece.

Current classification of proximal humeral fractures mainly relies on the classifications proposed by Charles Neer and the AO/OTA classification. Since the late 1980’s it has been known that intra- and inter-observer variation was high within the two systems. I conducted a series of observer studies to qualify the disagreement further and to study to what extent improvement of agreement could be obtained. No clinically significant differences in observer agreement were found at different levels of clinical experience, by reducing the number of categories, or by adding high quality radiographs, CT or 3D CT scans. A consistently low agreement on the Neer classification within and between untrained orthopaedic doctors was found. However, we also found that inter-observer agreement on treatment recommendation was higher than the agreement on the Neer classification. In a randomized trial we found that agreement could improve significantly by training of doctors, especially among specialists. However, classification of proximal humeral fractures remains a challenge for the conduct, reporting, and interpretation of clinical trials.

The evidence for the benefits of surgery in complex fractures of the proximal humerus is weak. In three systematic reviews I studied the outcome after locking plate osteosynthesis or reverse arthroplasty in complex fractures patterns. No randomized trials or well-conducted comparative studies were identified. High failure rates suggest that the use of these implants for complex fractures of the humerus should not be used outside clinical protocols. I recommend the conduct of randomized trials, and a design of such study is proposed.

Summary in Danish

Komplekse proksimale humerusfrakturer har været diagnosticeret og behandlet siden de tidligste kirurgiske tekster. Gennem mere end fire årtusinder var den foretrukne behandling traktion i knoglens længderetning efterfulgt af lukket reposition og immobilisering med linned behandlet med forskellige kombinationer af olie, honning, alun, vin eller voks. Bandagen blev efterfølgende stabiliseret med skinner af træ eller stift, tørret græs. Den forventede helingstid var fyrre dage. I fire ortopædihistoriske arbejder undersøger jeg den historiske udvikling af diagnostik, klassifikation og behandling af proksimale humerusfrakturer.

Nutidige klassifikationer af proksimale humerusfrakturer bygger hovedsaglig på Charles Neers og AO/OTAs klassifikationer. Imidlertid har det siden sidst i 1980erne været kendt at inter- og intra-observatør variationen indefor disse to systemer er høj. Jeg gennemførte seks observatørstudier og systematiske oversigter for at kortlægge denne uenighed nærmere, og for at afklare i hvilket omfang en forbedring af enigheden kunne opnås. Jeg fandt ingen klinisk betydende forskel på enigheden ved forskellige niveauer af klinisk erfaring, ved reduktion af antallet af kategorier, ved at anvende røntgenbilleder i særlig god kvalitet, eller ved at supplere med CT eller 3D CT scanninger. En gennemgående lav enighed blandt læger på en ortopædkirurgisk afdeling blev fundet. Jeg fandt imidlertid også at enigheden om behandlings-rekommendationer var højere end enigheden om klassifikation. I et randomiseret studie fandt jeg at enigheden kunne forbedres betydeligt gennem træning, særligt blandt speciallæger. Klassifikation af proksimale humerusfrakturer vedbliver dog at være udfordring for gennemførelse, rapportering og fortolkning af kliniske studier.

Evidensen for den gavnlige effekt af kirurgiske behandlinger af komplekse proksimale humerusfrakturer er svag. I tre systematiske oversigtsartikler undersøgte jeg resultaterne efter osteosyntese med vinkelstabile skinner eller ved primær indsættelse af revers protese ved komplekse frakturer. Jeg fandt ingen randomiserede studier eller velgennemførte komparative studier. Komplikationsrater omkring tredive procent tilsiger at disse implantater ikke bør anvendes udenfor protokoller ved komplekse proksimale humerusfrakturer. Jeg anbefaler gennemførelse af randomiserede studier og foreslår en protokol hertil.

Notes

References

- Malgaigne JF. Traité des fractures et des luxations. Paris, 1847.

- Vidus Vidius. Artis Medicinalis. In quo agitur de curatione membratim, hoc est, adcapite ad pedes. Vol. V. Frankfurt, 1596.

- Buhr AJ, Cooke AM. Fracture Patterns. Lancet 1959; 1: 531-6.

- Knowelden J, Buhr AJ, Dunbar O. Incidence of fractures inpersons over 35 years of age. Br J Prev Soc Med 1964;18: 130-41.

- Kiaer T, Larsen CF, Blicher J. [Proximal fractures of the humerus. An epidemiological and descriptive study of fractures]. Ugeskr Laeger 1986;148: 1894-7.

- Lind T, Kroner K, Jensen J. The epidemiology of fractures of the proximal humerus. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1989;108: 285-7.

- Bengner U, Johnell O, Redlund-Johnell I. Changes in the incidence of fracture of the upper end of the humerus during a 30-year period. A study of 2125 fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;(231) :179-82.

- Kannus P, Palvanen M, Niemi S, Parkkari J, Jarvinen M, Vuori I. Increasing number and incidence of osteoporotic fractures of the proximal humerus in elderly people. BMJ 1996;313: 1051-2.

- Palvanen M, Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J. Update in the epidemiology of proximal humeral fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;(442) :87-92.

- Roux A, Decroocq L, El BS, Bonnevialle N, Moineau G, Trojani C, Boileau P, de PF. Epidemiology of proximal humerus fractures managed in a trauma center. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012;98: 715-9.

- Lauritzen JB, Schwarz P, Lund B, McNair P, Transbol I. Changing incidence and residual lifetime risk of common osteoporosis-related fractures. Osteoporos Int 1993;3: 127-32.

- Lauritzen JB, Schwarz P, McNair P, Lund B, Transbol I. Radial and humeral fractures as predictors of subsequent hip, radial or humeral fractures in women, and their seasonal variation. Osteoporos Int 1993;3: 133-7.

- Brorson S. Management of fractures of the humerus in Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome: an historical review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467: 1907-14.

- Brorson S. Management of proximal humeral fractures in the nineteenth century: an historical review of preradiographic sources. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;(469) :1197-206.

- Neer CS. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52: 1077-89.

- Neer CS. Four-segment classification of displaced proximal humeral fractures. Instructional course lectures 1975;24: 160-8.

- Neer CS. Four-segment classification of proximal humeral fractures: purpose and reliable use. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002;11: 389-400.

- Müller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, Schatzker J The comprehensive classification of fractures of long bones. Berlin: Springer, 1990.

- Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, Broderick JS, Creevey W, DeCoster TA, Prokuski L, Sirkin MS, Ziran B, Henley B, Audige L. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium- 2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma 2007;21: S1-133.

- Ackermann C, Lam Q, Linder P, Kull C, Regazzoni. [Problems in classification of fractures of the proximal humerus]. Z Unfallchir Versicherungsmed Berufskr 1986;79: 209-15.

- Bernstein J, Adler LM, Blank JE, Dalsey RM, Williams GR, Iannotti JP. Evaluation of the Neer system of classification of proximal humeral fractures with computerized tomographic scans and plain radiographs. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78: 1371-5.

- Brien H, Noftall F, MacMaster S, Cummings T, Landells C, Rockwood P. Neer’s classification system: a critical appraisal. J Trauma 1995;38: 257-60.

- Kristiansen B, Andersen UL, Olsen CA, Varmarken JE. The Neer classification of fractures of the proximal humerus. An assessment of interobserver variation. Skeletal Radiol 1988;17: 420-2.

- Sidor ML, Zuckerman JD, Lyon T, Koval K, Cuomo F, Schoenberg N. The Neer classification system for proximal humeral fractures. An assessment of interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75: 1745-50.

- Sidor ML, Zuckerman JD, Lyon T, Koval K, Schoenberg N. Classification of proximal humerus fractures: The contribution of the scapular lateral and axillary radiographs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1994;3: 24-7.

- Siebenrock KA, Gerber C. The reproducibility of classification of fractures of the proximal end of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75: 1751-5.

- Sjoden GO, Movin T, Guntner P, Aspelin P, Ahrengart L, Ersmark H, Sperber A. Poor reproducibility of classification of proximal humeral fractures. Additional CT of minor value. Acta Orthop Scand 1997;68: 239-42.

- Sjoden GO, Movin T, Aspelin P, Guntner P, Shalabi A. 3D-radiographic analysis does not improve the Neer and AO classifications of proximal humeral fractures. Acta Orthop Scand 1999;70: 325-8.

- Majed A, Macleod I, Bull AM, Zyto K, Resch H, Hertel R, Reilly P, Emery RJ. Proximal humeral fracture classification systems revisited. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011;20(7: 1125-32.

- Bernstein J. Fracture classification systems: do they work and are they useful? J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76: 792-3.

- Burstein AH. Fracture classification systems: do they work and are they useful? J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75: 1743-4.

- Cowell HR. Patient care and scientific freedom. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76: 640-1.

- Neer CS. Fracture classification systems: do they work and are they useful? J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76: 789-90.

- Rockwood CAJr, . Fracture classification systems: do they work and are they useful? J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76: 790.

- Hoellen IP, Bauer G, Holbein O. [Prosthetic humeral head replacement in dislocated humerus multi-fragment fracture in the elderly--an alternative to minimal osteosynthesis?]. Zentralbl Chir 1997;122: 994-1001.

- Kristiansen B, Kofoed H. Transcutaneous reduction and external fixation of displaced fractures of the proximal humerus. A controlled clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70: 821-4.

- Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Internal fixation versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 3-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011;20: 747-55.

- Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J. Hemiarthroplasty versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 4-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011;20(7): 1025-33.

- Zyto K, Ahrengart L, Sperber A, Tornkvist H. Treatment of displaced proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997;79: 412-7.

- Bhandari M, Matthys G, McKee MD. Four part fractures of the proximal humerus. J Orthop Trauma 2004;18: 126-7.

- Handoll HH, Ollivere BJ. Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010: CD000434.

- Kontakis G, Koutras C, Tosounidis T, Giannoudis P. Early management of proximal humeral fractures with hemiarthroplasty: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90: 1407-13.

- Lanting B, MacDermid J, Drosdowech D, Faber KJ. Proximal humeral fractures: a systematic review of treatment modalities. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008;17: 42-54.

- Misra A, Kapur R, Maffulli N. Complex proximal humeral fractures in adults--a systematic review of management. Injury 2001;32: 363-72.

- Nanidis TG, Majed A, Liddle AD, Constantinides VA, Sivagnanam P, Tekkis PT, Reilly P, Emery RJ. Conservative versus operative management of complex proximal humeral fractures: a meta-analysis. Shoulder & Elbow 2010;2: 166-74.

- Tingart M, Bathis H, Bouillon B, Tiling T. [The displaced proximal humeral fracture: is there evidence for therapeutic concepts?]. Chirurg 2001;72: 1284-91.

- Ilchmann T, Ochsner PE, Wingstrand H, Jonsson K. Non-operative treatment versus tension-band osteosynthesis in three- and four-part proximal humeral fractures. A retrospective study of 34 fractures from two different trauma centers. Int Orthop 1998;22: 316-20.

- Iyengar JJ, Devcic Z, Sproul RC, Feeley BT. Nonoperative Treatment of Proximal Humerus Fractures: A Systematic Review. J Orthop Trauma 2011;25(10): 612-7.

- Leyshon RL. Closed treatment of fractures of the proximal humerus. Acta Orthop Scand 1984;55: 48-51.

- Lill H, Bewer A, Korner J, Verheyden P, Hepp P, Krautheim I, Josten C. [Conservative treatment of dislocated proximal humeral fractures]. Zentralbl Chir 2001;126: 205- 10.

- Urgelli S, Crainz E, Maniscalco P. [Conservative treatment vs prosthetic replacement surgery to treat 3- and 4-fragment fractures of the proximal epiphysis of humerus in the elderly patient]. La Chirurgia degli organi di movimanto 2005;90: 345-51.

- Zyto K. Non-operative treatment of comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus in elderly patients. Injury 1998;29: 349-52.

- Den HD, De HJ, Schep NW, Tuinebreijer WE. Primary shoulder arthroplasty versus conservative treatment for comminuted proximal humeral fractures: a systematic literature review. Open Orthop J 2010;4: 87-92.

- Gautier E, Sommer C. Guidelines for the clinical application of the LCP. Injury 2003;34 Suppl 2: B63-B76.

- Haidukewych GJ. Innovations in locking plate technology. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004;12: 205-12.

- Miranda MA Locking plate technology and its role in osteoporotic fractures. Injury 2007;38 Suppl 3: S35-S39.

- Sommer C, Gautier E, Muller M, Helfet DL, Wagner M First clinical results of the Locking Compression Plate (LCP). Injury 2003; 34 Suppl 2: B43-B54.

- Bjorkenheim JM, Pajarinen J, Savolainen V. Internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with a locking compression plate: a retrospective evaluation of 72 patients followed for a minimum of 1 year. Acta Orthop Scand 2004;75: 741-5.

- Hente R, Kampshoff J, Kinner B, Fuchtmeier B, Nerlich M. [Treatment of dislocated 3- and 4-part fractures of the proximal humerus with an angle-stabilizing fixation plate]. Unfallchirurg 2004;107: 769-82.

- Hessler C, Schmucker U, Matthes G, Ekkernkamp A, Gutschow R, Eggers C. [Results after treatment of instable fractures of the proximal humerus using a fixed-angle plate]. Unfallchirurg 2006;109: 867-4.

- Kilic B, Uysal M, Cinar BM, Ozkoc G, Demirors H, Akpinar S. [Early results of treatment of proximal humerus fractures with the PHILOS locking plate]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2008;42: 149-53.

- Korkmaz MF, Aksu N, Gogus A, Debre M, Kara AN, Isiklar ZU. [The results of internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with the PHILOS locking plate.]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2008;42: 97-105.

- Koukakis A, Apostolou CD, Taneja T, Korres DS, Amini A. Fixation of proximal humerus fractures using the PHILOS plate: early experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;(442) :115-20.

- Papadopoulos P, Karataglis D, Stavridis SI, Petsatodis G, Christodoulou A. Mid-term results of internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with the Philos plate. Injury 2009;40: 1292-6.

- Ricchetti ET, DeMola PM, Roman D, Abboud JA. The use of precontoured humeral locking plates in the management of displaced proximal humerus fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17: 582-90.

- Shahid R, Mushtaq A, Northover J, Maqsood M. Outcome of proximal humerus fractures treated by PHILOS plate internal fixation. Experience of a district general hospital. Acta Orthop Belg 2008;74: 602-8.

- aap Implantate Proximale Humerusplatte (technical manual). PrFont34Bin0BinSub0Frac0Def1Margin0Margin0Jc1Indent1440Lim0Lim1 http: //w ww aap de/en/Produkte/Osteosynthese/Winkelstabile_Platten/Proximale_Humerusplatte/inde x_html 2010.

- Stryker Technical manual. http: //www shoulderdoc co uk/documents/Numelock pdf 2010.

- Synthes PHILOS (technical manual). PrFont34Bin0BinSub0Frac0Def1Margin0Margin0Jc1Indent1440Lim0Lim1 http: //w ww shoulderdoc co uk/documents/Philos pdf 2010.

- Zimmer NCB Proximal Humerus Plating (technical manual). PrFont34Bin0BinSub0Frac0Def1Margin0Margin0Jc1Indent1440Lim0Lim1 http: //www.zimmer.com/web/enUS/pdf/surgical_techniques/NCB_Proximal_Humerus_Plating_System_ Surgical_Technique_Part1 pdf 2010.

- George T, Dederichs A, Bellan D, Chaumont PL, Charvet R, Coudane H. Reversed prosthesis for management of complex proximal humeral fractures: a prospective monocenter study [abstract]. 22rd Congress of SECEC, Madrid 2009.

- Grisch D, Riede U, Gerber C, Jost B. Inverse total shoulder arthroplasty as primary treatment for complex proximal humerus fractures in the elderly [abstract]. 23rd Congress of SECEC, Lyon 2011.

- Klein M, Juschka M, Hinkenjann B, Scherger B, Ostermann PA. Treatment of comminuted fractures of the proximal humerus in elderly patients with the Delta III reverse shoulder prosthesis. J Orthop Trauma 2008;22: 698-704.

- Lenarz C, Shishani Y, McCrum C, Nowinski RJ, Edwards TB, Gobezie R. Is reverse shoulder arthroplasty appropriate for the treatment of fractures in the older patient?: early observations. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;(469) :3324-31.

- Reuther F, Proust J, Kohut G, Nijs S. Specially designed inverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of complex proximal humeral fractures [abstract]. 23rd Congress of SECEC, Lyon 2011.

- Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. Long term functional outcome following reverse shoulder arthroplasty in the elderly. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2011;97(6): 583-9.

- Riedel BB, Mildren ME, Jobe CM, Wongworawat MD, Phipatanakul WP. Evaluation of the learning curve for reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2010: 237-41.

- Rockwood CAJr., The reverse total shoulder prosthesis. The new kid on the block. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89: 233-5.

- Gerber C. Complications and revisions of reverse total shoulder replacements. Nice Shoulder Course 2006.

- Cooper A. On the dislocation of the os humeri upon the dorsum scapulae, and upon fractures near the shoulder-joint. Guy’s Hospital Reports 1839;IV: 265-84.

- Allen JP. The art of medicine in Ancient Egypt. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005.

- Breasted JH. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: published in facsimile and hieroglyphic transliteration with translation and commentary in two volumes. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1930.

- Hippocrates. Oeuvres complètes d’Hippocrate (translation by É. Littré). Vol. 3. Paris: J.-B. Baillière, 1841.

- Hippocrates. On Fractures (translation by E.T. Withington). In: Hippocrates. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1928: 95-199.

- Oribasii Collectionum Medicarum Reliqviae (ed. Ioannes Raeder). Vol. IV, 1933.

- Celsus (translation by W.G. Spencer) De Medicina. Vol. III. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1938.

- Albucasis. On surgery and instruments: a definitive edition of the Arabic text with English translation and commentary by M.S. Spink and G.L Lewis. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

- Velpeau A. Nuveaux éléments de médicine opératoire, 5th ed. Paris, 1840.

- Leonardo da Vinci. Quaderni d’Anatomia, I-VI (published by Vangensten OCL; Fonahn A; Hopstock H). Christiania: Jacob Dybwad, 1911.

- Leonardo da Vinci. Atlas der anatomischen Studies in der Sammlung Ihrer Majestät Queen Elizabeth II in Windsor Castle. Vol. III. Gütersloh: Prisma Verlag, 1978.

- Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo on the human body (translation by O’Malley and Saunders). New York: Dover Publications, 1983.

- Duverney M. The diseases of the bones (translated by Samuel Ingham). London: Tho. Osborne, 1762.

- Desault PJ, Chopart F. Traité des maladies chirurgicales. Vol. 1-2. Paris, 1796.

- Desault PJ. Oeuvres chirurgicales. Première partie: maladies des parties dures. Paris, 1798.

- Desault PJ. A treatise on fractures, luxations, and other affections of the bones (translated by Charles Caldwell). Philadelphia: Fry and Kammerer, 1805.

- Cooper A. A treatise on dislocations; and on fractures of the joints (first published 1822), 2nd. ed. London, 1823.

- Cooper A. A treatise on fractures and dislocations of the joints. Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea, 1851.

- Smith RW. A treatise on fractures in the vicinity of joints and on certain forms of accidental and congenital dislocations. Dublin, 1847.

- Malgaigne JF. Mémoir sur les fractures de l’extrémité supérieure de l’humérus. Journal de Chirurgie 1845;III: 257-64.

- Thudichum L. Ueber die am oberen Ende des Humerus vorkommende Knochenbruche (dissertation). Giessen: J. Ricker’sche Buchandlung, 1851.

- Liston R. Practical surgery, 2nd ed. London: John Churchill, 1838.

- Stimson LA. A practical treatise on fractures and dislocations. New York: Lea Brothers & Co., 1899.

- Hoffa A, Grashey R. Verbandlehre (first published 1897), 5th ed. München: J.F. Lehmans Verlag, 1914.

- Hoffa A. Lehrbuch der frakturen und luxationen für ärzte und studierende (first published 1888). Würzburg, 1891.

- Bacon LW. On the history of the introduction of plaster of paris bandages as a fixation dressing. Bulletin of the Society of Medical History of Chicago 1923;3: 122-32.

- van Assen J, Meyerding HW. Antonius Mathijsen, the discoverer of the plaster bandage. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1948;30-A: 1018-9.

- van Rens TJ. The history of treatment using plaster of Paris. Acta Orthop Belg 1987;53: 34- 9.

- Kocher T. Beiträge zur Kenntniss einiger Praktisch wichtiger Fracturformen. Basel: Carl Sallmann, 1896.

- Röntgen W. On a new kind of rays. Nature 1896: 274-6.

- Codman EA. The shoulder: rupture of the supraspinatus tendon and other lesions in or about the subacromial bursa. Malabar, Florida: Krieger, 1934.

- Neer CS, Brown THJr., , Mclaughlin HL. Fracture of the neck of the humerus with dislocation of the head fragment. Am J Surg 1953;85: 252-8.

- Gerber C, Werner CM, Vienne P. Internal fixation of complex fractures of the proximal humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86: 848-55.

- Court-Brown CM, Garg A, McQueen MM. The epidemiology of proximal humeral fractures. Acta Orthop Scand 2001;72: 365-71.

- Murray D, Zuckerman JD. Four-part fractures and fracture-dislocations. In: Zuckerman JD, Koval KJ, eds. Shoulder Fractures. The Practical Guide to Management. New York: Thieme, 2005.

- Tamai K, Ishige N, Kuroda S, Ohno W, Itoh H, Hashiguchi H, Iizawa N, Mikasa M. Four-segment classification of proximal humeral fractures revisited: a multicenter study on 509 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009;18: 845-50.

- Siwach R, Singh R, Rohilla RK, Kadian VS, Sangwan SS, Dhanda M. Internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with locking proximal humeral plate (LPHP) in elderly patients with osteoporosis. J Orthop Traumatol 2008;9: 149-53.

- Yang H, Li Z, Zhou F, Wang D, Zhong B. A prospective clinical study of proximal humerus fractures treated with a locking proximal humerus plate. J Orthop Trauma 2011;25: 11-7.

- Nicholson GP, Strauss EJ, Sherman SL Scapular notching: Recognition and strategies to minimize clinical impact. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;(469) :2521-30.