Abstract

This article examines the relationship of curriculum and didactics through a social realist lens. Curriculum and didactics are viewed as linked and integrated by the common issue of educational content. The author argues that the selection of educational content and its organisation is a matter of recontextualising principles and that curriculum and didactics may be understood as interrelated stages of such recontextualisation. Educational policy and the organisation of pedagogic practice are considered as distinct although closely related practices of ‘curricularisation’ and ‘pedagogisation’. Neo-Bernsteinian social realism implies a sociological approach by which educational knowledge is recognised as something socially constructed, but irreducible to power struggles in policy arenas. More precisely, curriculum and didactics are not only matters of extrinsic standpoints. Recontextualising practices may also involve intrinsic features, that is, some kind of relatively generative logics that regulate curriculum design as well as pedagogic practice. In order to highlight certain implications for both curriculum and didactic theory, the author develops a typology that is analytically framed by principles of extrinsic relations to and intrinsic relations within curriculum or didactics.

In the current ‘knowledge society’, economic increase and the improvement of human condition are to a great extent dependent on the flow of knowledge: its creation, exchange and reproduction. The transmission of knowledge is a highly topical issue, standing at the centre of educational policy and posing such questions as ‘What knowledge is the most valuable?’ and ‘How should knowledge be organised for learning?’ At the same time, knowledge is somewhat problematic for curriculum theory. Ever since the ‘new’ sociology of education emerged in the 1970s, knowledge has been recognised as socially constructed knowledges. Since social constructions are ideologically saturated, educational knowledge is arbitrary, and therefore a curriculum will reflect the power struggles that formed it. Constructivist approaches to teaching and learning have affected the field of didactics in a similar manner. We are increasingly inclined to focus on the knowing of knowers than on the knowledge of the known (cf. Maton, Citation2014). These tendencies point to the critical relationship between educational content and knowledge, the theme of this paper.

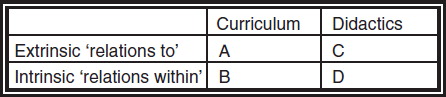

The issue of educational knowledge and content will be addressed from a social realist point of view. Social realism, however, rather than being a defined ism, is a heterogeneous school of thought or ‘coalition of minds’ (Maton & Moore, Citation2010). Thus, what follows is a non-empiricist investigation of principles established by a social realist approach to curriculum and didactics. First, the correlation of curriculum and didactics will be examined in order to designate a common denominator: the issue of educational content.Footnote1 Second, Basil Bernstein's description of recontextualisation will be explored as an aid to further conceptualisation and reasoning. We will also consider arguments of the social realist movement and give voice to its founders. Then the implications of those concepts examined will be demonstrated by means of a typological analysis (). The aim of the latter is to present an organising framework that will conceptualise types of substantive studies.

Curriculum and didactics

Curriculum theory is concerned with how knowledge is selected and organised for learning under historical, cultural and social conditions. In such a content-oriented curriculum theory, the focus is on the selection and legitimation of knowledge, the ways in which this knowledge is distributed and how the regulation of knowledge is associated with educational identities, consciousness and power.

Curriculum as Content raises questions like: ‘what knowledge is of most worth’, ‘what counts as knowledge’ and ‘what kind of knowing, learning or abilities do various pedagogic texts and practices promote or prevent’? The selection of knowledge, the arguments and principles used for inclusion or exclusion, content organization, and the consequences of various selections and arrangement are at the centre. (Forsberg, Citation2007, p. 11)

‘What counts as knowledge’ is also an issue of ‘whose knowledge’, since knowledge is always ‘someone's knowledge’ (Englund, Forsberg, & Sundberg, Citation2012). Therefore, educational knowledge consists of symbols that carry meaning, and a curriculum is the medium of conveying meaning, liberation, reproduction, inclusion and exclusion. Since curriculum theory commonly interrelates questions about content with other practice-oriented issues, such as how objectives and pedagogies are formed in given societies and cultures (Lundgren, Citation1979), curriculum theory is at the same time the knowledge practice of didactics.

DidaktikFootnote2 (in the German sense) comprises the professional knowledge of teaching and learning (Gundem & Hopmann, Citation1998). The field of Didaktik research includes descriptive analyses of pedagogic practice as well as prescriptive principles for planning and instruction (Jank & Meyer, Citation1997/1991). One of the fundamental issues concerns content as a meaningful body of knowledge. Content says something, that is, it carries a certain potential of meaning through associations with a selective tradition. Choosing a content involves selecting an offer of meaning (Englund, Citation1998). In this way, curriculum and Didaktik are interconnected by the content that is at their core. Using this integrated approach, content may be considered in terms of rationale, aims and objectives within a particular social and historical context (Englund & Svingby, Citation1986).

However, there are differences between curriculum and Didaktik. While curriculum theory has largely been focused on the social construction of educational knowledge, Didaktik has been concerned with sites of teaching and learning (Hopmann & Riquarts, Citation2000). Curriculum theory recognises content as the result of a power play; Didaktik understands it as an outgrowth of teachers’ reflective practice. On the one hand, content is organised by system of social and epistemic relations. On the other, there is a professional, interpretative, reflective agent in the person of the teacher (Westbury, Citation1998, Citation2000). The system prescribes educational policy, while the teacher draws upon knowledge practices. The dividing line may be the differences in orientation towards subjects or knowers. While curriculum theory is oriented to the collective (e.g., in a Durkheimian sense), Didaktik tends to focus upon the individual (e.g., according to a Kantian tradition) (cf. Gellner, Citation1992; Young, Citation2008).

One might argue that curriculum theory and Didaktik vary by their separate perspectives, although these are mostly due to different ‘languages of description’ (cf. Bernstein, Citation2000). Despite their conceptual differences, they may be addressed in a generally integrated manner in order to avoid implying that curriculum and didactics are isolated entities. It would be incorrect to view curriculum as a symbolic order of norms and values versus didactics as the hub for theories of teaching and learning. On the contrary, both regulative and instructional discourses should be considered under the order of an integrated pedagogic discourse.

In elucidating curriculum and didactics, useful guidance is provided by Bernstein's ‘On the classification and framing of educational knowledge’. Its appearance in Knowledge and Control (Citation1971) represented the ‘new’ sociology of education. However, Bernstein's article may also be regarded as a decisive departure from the Anglo-Saxon recognition of didactics as instruction. Bernstein acknowledges being influenced by the German tradition, especially Klafki's and Huppauf's ‘constructive criticism’ (p. 68). This observation can be compared with a statement in the last volume of Bernstein's CCC (Citation2000). In the introduction to chapters 6 and 8, he refers to the German philosopher Ernst Cassirer as one of his most significant influences (Durkheim was the other). Thus, although Bernstein did not use the concept of Didaktik or didactics, we can interpret his theories of pedagogic practice against the background of the German tradition of Didaktik (cf. Young, Citation2008).

The recontextualisation of knowledge and educational content

Issues of educational knowledge, that is, what the content of curriculum and didactics should consist of, is a matter of discourse. Bernstein (Citation2000) suggests that ‘pedagogic discourse is a recontextualising principle … which selectively appropriates, relocates, refocuses, and relates other discourses to constitute its own order’ (p. 33 [italics in original]). Thus, pedagogic discourse removes other discourses from their substantive contexts and relocates them in accordance with specific principles. In this way, strongly classified discourses from various types of practices can be intertwined and integrated to a particular order of pedagogic discourse. Recontextualising processes express educational policy and hence are commonly framed as processes of curriculum formation. However, in recontextualising processes, one also confronts didactic issues, not the least of which is the question of ‘what’ (that is, the classification of content) and ‘how’ – matters of framing due to different kinds of theories (Bernstein, Citation1990).

In the classical model of the pedagogic device (Bernstein, Citation1990, Citation2000), recontextualising processes are emplaced within an intermediate field between (knowledge) production and (educational) reproduction.Footnote3 In a reformulated version, Maton (Citation2014) suggests that knowledge is ‘curricularised’ from fields of knowledge production and that educational knowledge is in turn ‘pedagogised’ into sites of teaching and learning. But Maton also indicates reverse processes, namely, that educational knowledge is ‘recurricularised’ by the field of pedagogic practice. More precisely, recurricularisation may occur as a consequence of enacted educational knowledge.

One could, therefore, reconceptualise curriculum and didactics as two interrelated types of recontextualising practices, with both having their respective logics:

Curricular logics regulate how knowledge is selected, transformed, relocated and defined as official educational knowledge.

Didactic logics regulate educational content by frames of teaching and learning in formal pedagogic practice.

Whereas the curricularisation of knowledge is affected by struggles between recontextualising fields, pedagogisation refocuses selected knowledge taking into account principles and strategies of teaching and learning.

Since pedagogic discourse is a recontextualising principle, curriculum structure cannot solely rest upon knowledge structures. Furthermore, subject matter didactics are neither physics, history, nor any other specific academic discipline. They are processes by agents within fields of recontextualisation (Bernstein, Citation1990). In addition, ‘every time a discourse moves from one position to another, there is a space in which ideology can play. No discourse ever moves without ideology at play’ (Bernstein, Citation2000, p. 32). This is crucial to curriculum and didactics because if there is always a discursive gap, there will never be a curricula or didactic approach beyond ideology. However, this recognition does not mean that curriculum and didactics, in general, and educational knowledge, in particular, must be reduced to standpoint theories.

Extrinsic or intrinsic?

Since the early 1970s, the ‘new’ sociology of education has considered educational knowledge in terms of power struggles between social groups with contending interests. Curriculum theorists have, therefore, been occupied with ‘identifying the interests of those with power to select knowledge for the curriculum’ (Young, Citation2008, p. 81).

For instance, a so-called ‘dominant’ or ‘hegemonic’ form of knowledge, represented in the school curriculum, is identified as ‘bourgeois’, ‘male’, or ‘white’ – as reflecting the perspectives, standpoints and interests of dominant social groups …. Knowledge forms and knowledge relations are translated as social standpoints and power relationships between groups. This is more a sociology of knowers and their relationships than of knowledge. (Moore & Muller, Citation1999, p. 190)

The above authors argue that both reproduction and standpoint theories, wherein curriculum is class, ethnicity and gender, lead to the recognition of knowledge as arbitrary claims and to the reduction of knowledge to knowers. The rationale behind it is found in underlying principles of post-structuralism, postmodernism and constructivism. Despite the fundamental differences between the three approaches above, there is a pervasive tendency to establish and maintain what Alexander (Citation1995) has termed the ‘epistemological dilemma’, that is, a false dichotomy between positivist absolutism and constructivist relativism. The dichotomy seems to be between educational knowledge as universal, disinterested and decontextualised, or educational knowledge as socially constructed by historical, cultural and ideological conditions (Maton & Moore, Citation2010). Choosing the latter will result in relativism and perspectivism (Moore & Young, Citation2001). What distinguishes the use of relativism and perspectivism in the sociology of education is the questioning of the origins and the legitimacy of objectified school knowledge.

Since the millennium, social realists have been seeking an alternative approach to the sociology of education and to the related yet distinct discipline of the sociology of knowledge, where the legitimation of educational knowledge can be understood as something more than a power play between dominating and subordinated groups (Young, Citation2008). A social realist approach to curriculum and didactics is ‘social’ because it recognises knowledge as socially constructed in practice. Knowledge is neither universal, nor is it a given, unmediated representation of the world; rather, it is a fallible product under social, cultural and historical constraints. At the same time, social realism is ‘realist’ in the sense that knowledge is about something independently real in an objective world beyond discourse (Maton, Citation2014; Wheelahan, Citation2010; Young, Citation2008). Epistemological relativism as used here does not have to slip into judgmental relativism and imply that knowledges are ‘equally related’. Instead, there could be principles ‘for determining the relative merits of competing claims to insight’ (Maton, Citation2014, p. 10). In sum, we do not construct knowledge by ourselves; it is intersubjectively created, recontextualised and reproduced by agents in knowledge practices (Maton, Citation2014). One could derive the underlying concept of objectivity from Durkheimian thought that knowledge has an objectivity bestowed on it by its ‘sacredness’, since collective representations go beyond the experiences of particular individuals. In this sense, knowledge is ‘what society has demonstrated to be true’ (Young & Muller, Citation2007, p. 185).

Social realist approaches to knowledge stress that although all knowledge is historical and social in origins, it is its particular social origins that give it its objectivity. It is this objectivity that enables knowledge to transcend the conditions of its production. It follows that the task of social theory is to identify these conditions. (Young, Citation2008, p. 146)

The consequence of the above reasoning is that the sociology of education would have to take into account an equipoise of views, for example, increasingly focus on the intrinsic features of knowledge.

In addition to showing the socially and historically located nature of knowledge practices, the way power shapes knowledge, one needs also to show how knowledge shapes power and that the power of knowledge is not just social but also epistemic. (Maton, Citation2014, p. 41)

Following Bernstein (Citation1990, Citation2000), we can distinguish between theories of relations to and relations within education. From this point of view, sociological analyses of education have largely been focused on different kinds of ‘relations to’ education, typically relations of class, ethnicity and gender to curriculum and pedagogic practice. By contrast, ‘relations within’ education, its intrinsic structures, have rarely been taken into account. Nevertheless, such a ‘social realist statement’ should be treated with caution, particularly in regard to frame factor theory, which brought together external sociologies of education and analyses of relations within pedagogic practice.Footnote4

[T]heories of cultural reproduction, resistance, or transformation offer relatively strong analyses of ‘relation to’, that is, of the consequences of class, gender, race in the unequal and invidious positioning of pedagogic subjects with respect to the ‘privileging text’, but they are relatively weak of analyses of ‘relations within’ (perhaps with some exceptions, e.g., U. Lundgren). (Bernstein, Citation1990, p. 178)

One curricular and didactic implication of bringing ‘relations to’ and ‘relations within’ together is the creation of frameworks that not only analyse contextual aspects of education but also content in relation to its contexts. In doing so, it may be seen that ‘knowledge is emergent from but irreducible to the practices and contexts of its production and recontextualization, teaching and learning’ (Maton & Moore, Citation2010, p. 5 [italics in original]). Therefore, curriculum theory and didactics must comprise both the internal ordering of knowledge production and the logics of recontextualisation: curricularisation – pedagogisation – recurricularisation (cf. Bernstein, Citation2000; Maton, Citation2014; Wheelahan, Citation2010; Young, Citation2008).

Implications for curriculum and didactics

Extrinsic ‘relations to’ curriculum and didactics are concerned with how extrinsic ideas (inter alia ~isms) affect these fields, and how social groups (e.g., political parties, researchers and teachers) are positioned in their relations to curricular or didactic design. Intrinsic ‘relations within’ are the logics whereby curricula and didactic conceptions are internally regulated.

Extrinsic relations to curriculum

Sociopolitical groups have their respective ideological interests and thus diverse relations to curriculum as symbolic structure and control. Relations are in this case external because the principle of recontextualisation is itself in a sense external to curriculum. This may be illustrated by two contemporary ~isms in educational policy: neo-liberalism and neo-conservatism. The core recontextualising principle of neo-liberalism can be called marketisation because the selection of content is regulated by market demands. Neo-liberalism desires a relatively weak classification between the fields of education and socio-economic production so that the latter may control the output of the former. Neo-conservative discourses similarly focus on the exchange value of educational content, at the same time that control over the selection of content is stronger in accordance with the conservative view of knowledge as autonomous (Bernstein, Citation2000; Moore, Citation2013). The point is twofold: First, if there are different ~isms, there will be different recontextualising principles. The issue of ‘what counts as knowledge in curriculum’ depends on the underlying principle. Second, since the pedagogic discourse integrates discourses according to its own order, it may consist of seemingly disparate discourses (or ways of counting) under an integrated order of discourse (Fairclough, Citation2010), for example, the integrated order of ‘the New Right’ (cf. Apple, Citation2004, Citation2006; Ball, Citation1998; Beck, Citation2006).

The above example points to interrelated relations of extrinsic character. Initially, as marketisation becomes the recontextualising principle, the relative autonomy of educational knowledge will be weakened (Beck, Citation1999). Second, such an instrumentally extrinsic relation to education must be conveyed by recontextualising agents related to education. There are not only principles in operation here, but sociopolitical groups as well. Moreover, recontextualising principles are also associated with logics of distribution.

How knowledge should be distributed is among the most frequently asked questions in educational policy because access to knowledge is intertwined with the division of labour, inclusion and inequality (Maton & Muller, Citation2007). Externalist sociological theories are concerned with privileged knowledge – the legitimation and distribution of knowledge – but less so with the distinctive features of that knowledge (Bernstein, Citation1990).

Intrinsic relations within a curriculum

No matter which government is in office, or how sociopolitical groups relate to education, there will still be some kind of intrinsic relations within a curriculum as a relatively generic structure. In order to outline such an intrinsic logic, Bernstein (Citation1999) distinguishes between two fundamental classes of knowledge: sacred/esoteric or principled knowledge and profane/mundane or everyday knowledge. This classification is recontextualised through societies, although the content of the sacred and the profane varies with time and context. Sacred knowledge, which Bernstein terms vertical discourse, is esoteric due to its structure and potential. While everyday knowledge, or horizontal discourse, is segmented and context-dependent, esoteric knowledge is systematised and may by its principled character be recontextualised across meanings and practices. Verticality in knowledge would thus provide opportunities for enlightenment and emancipation (cf. Muller, Citation2007; Wheelahan, Citation2010; Young, Citation2008). Since this theoretical division has been expanded in a variety of theories, it is difficult to circumscribe its full meaning. However, through this kind of conceptualisation, social realists have investigated ways of conceptualising powerful knowledge and have discussed consequences of the differentiated distribution of that knowledge, rather than restricting educational knowledge so that it remains the knowledge of the powerful (Young, Citation1998).

If one compares curricula from different periods, some recurring elements will probably be found. Such features include basic classifications between phenomena, inter alia ages (knowers) or school subjects (knowledge practices). Divisions of this kind are central to curriculum formation because they represent the intrinsic grammar of curriculum design (cf. Bernstein, Citation2000). The pedagogic discourse that social groups structure by means of recontextualising processes is therefore to some extent determined by prescriptive conceptions.

Boundaries between school subjects may be set by a predefined order that acts selectively on the recontextualisation of knowledge. When educational knowledge is legitimised within educational policy, it is concerned with specific disciplines, rather than knowledge itself. Once school subjects are legitimated, processes of organisation within given subjects will begin. Whereas the distribution of knowledge is divided and regulated by socio-economic structures, subject-oriented content is distributed and framed according to age. Since students are divided by age, educational content must similarly be divided into stages of knowledge. Or is it that students are organised in accordance with knowledge structures and intrinsic logics of cumulative knowledge-building? However, this is an expression of curricularisation, while the pedagogic practice has more leeway due to didactic logics. We know from the notion of recontextualisation that educational knowledge is not purely knowledge because wherever there is a transmission of discourse ‘there is a place for ideology to play’ (Bernstein, Citation2000, p. 9). Therefore, the potential or actual interrelationship between social hierarchies and epistemic hierarchies will continue to be a vital issue for the sociology of education.

Extrinsic relations to didactics

Educational policy will always include a pedagogic recontextualising field in which discourses on teaching and learning take place. This type of discursive practice is thus linked by extrinsic relations to didactics. Different ways of relating to didactics are regulated by the discursive order of pedagogic discourse. Conflicting discourses can therefore exist between the official pedagogic discourse promulgated by the state and its administrators, and the pedagogic discourse represented by schools of education (Bernstein, Citation1990, Citation2000; cf. Lindensjö & Lundgren, Citation2000). Thus, there will be dissimilar pedagogic discourses, and various social groups will relate to these discourses in different ways. In each of these groups, there will be tenable forms of didactics, as well as ways that are untenable (cf. Bernstein, Citation2000).

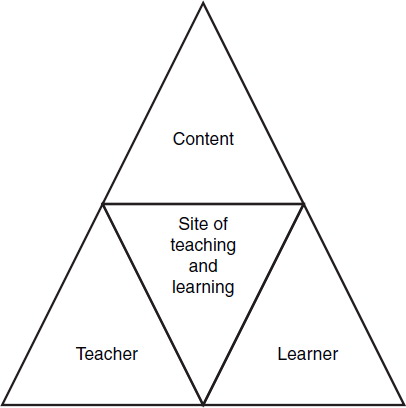

Depending on one's orientation to alternate pedagogies and didactic conceptions, different principles of organisation may apply to the governance of pedagogic processes. Such principles can, for example, be the focus of didactics. Didactic conceptions may concentrate differently with regard to ‘the didactic triangle’ (): either on content, on the teacher, or on the learner.Footnote5

Consideration of the relationship between teacher and learner is a classical one. There is a never ending debate as to whether the teacher or the learner should be the central point of didactics. Conceptions like ‘teacher-centred pedagogy’ and ‘learner-centred pedagogy’ are generally well known, sometimes in terms of ~isms such as traditionalism versus progressivism. The former usually sees teaching and learning as processes of transmission and acquisition, while the latter tends to view them in terms of interpretation, construction and meaning-making (Maton, Citation2014). From a social realist point of view, emphasis on the one or the other could be reductionist. If the focus is on the teacher, recontextualising processes could be reduced to what is individually interpreted by that particular teacher and what fits his or her didactic approach. Moreover, the recontextualisation of knowledge may be limited by the instructional discourse so that it becomes bound by rules of instruction and evaluation. Content is selected on the basis of its potential to be pedagogised and organised as instructional (and evaluated) content. The ‘how’ will then become the recontextualising principle of ‘what’. On the other hand, if the focus is on the learner, the recontextualisation of knowledge might be confined to student input: their interests and experiences taken from everyday life. Content would then be selected from students’ ‘life-worlds’, authentically relocated with regard to their cultures, and situated for the benefit of their experiential learning (cf. Maton, Citation2014). In this way, the selection of content is not so much about recontextualising knowledge from the field of knowledge production, but more like recontextualising experiences from everyday life. By selecting one of the options presented – teacher-centred or learner-centred – any particular didactic issue of ‘what’ is in fact an issue of ‘who’, because rather than a choice of ‘what knowledge’, there is only a choice of ‘whose knowledge’ (cf. Moore, Citation2009). In this way, knowledge is reduced to knowers (either/or) and objectives are reduced to experiences of subjects (teacher/learner).

For a social realist, there is no problem with teacher-centred or learner-centred approaches, except that focusing on a given issue also implies peripheral matters. While it is problematic if teacher and learner are conceptualised as opposed positions, there is also a tendency to overlook the significance of content. If didactics are presented as either teaching or learning, and nothing else, there will be a ‘didactic dilemma’, and a didactic triangle in a classical sense will no longer exist. The social realist will argue that we have to ‘bring knowledge back in’ to didactics (Young, Citation2008), not as instructional content or personal experience, but as esoteric knowledge. It follows that educational content cannot be based primary on student experiences. Moreover, didactics must differentiate between formal learning in school and informal learning outside an educational institution (Young & Muller, Citation2010).

Intrinsic relations within didactics

Regardless of our social relations to different types of didactic conceptions, those didactics or pedagogies are inevitably formulated with regard to the ‘inner logic’ of pedagogic practice. When Bernstein (Citation1990) speaks of inner logic, he is ‘referring to a set of rules which are prior to the content to be relayed’ (p. 64). In other words, there are ordering principles of pedagogic practice.

Irrespective of didactic ideas there also has to be a hierarchical relationship between teacher and learner (cf. Bernstein, Citation1990, p. 64). Social relations to didactics may seek to weaken the framing of pedagogic practice – that is, the teacher's control of the processes – but social realism reminds us that there must be hierarchies. Otherwise the distinction between teacher and learner will cease, and then something called schooling cannot exist, nor can there be a concept of didactics in practice. Since teaching has to occur over time, and since learning also requires time ‘for some grass to grow’, the logics of sequencing and pacing must affect the organisation of pedagogic practice. If there is an intrinsic progression of educational knowledge, and if teaching endeavours to bring about cumulative knowledge-building, then sequencing, pacing, but also evaluation, is necessary (Bernstein, Citation1990).

Bernstein conceptualised two generic types of logics according to the principle of sight as visible and invisible pedagogies. The former is explicit with regard to its regulative and instructional rules, while the latter is organised by implicit rules relatively invisible to the learner (Bernstein, Citation1990). Thus, pedagogies may be described by ordering principles rather than as having different standpoints. Instead of simply distinguishing between two types of ideological ‘relations to’ didactics – conservatism versus progressivism – Bernstein explored what these standpoints are struggling over: the fundamental grammar and intrinsic relations of pedagogic practice.

According to Bernstein (Citation1990), differences in pedagogies ‘will clearly affect both the selection and the organization of what is to be acquired, that is, the recontextualizing principle adopted to create and systematize the contents to be acquired and the context in which it is acquired’ (pp. 71–72). More precisely, if didactic logics regulate matters of ‘how’, ‘then any particular “how” created by any one set of rules acts selectively on the “what”of the practice, the form of its content. The form of the content in turn acts selectively on those who can successfully acquire’ (Bernstein, Citation1990, p. 63). Thus, Bernstein explicitly conceptualises a recontextualising principle for the organisation of general didactics. The rationale of general didactics is a matter of ‘how’, as well as how social groups relate differently to diverse types of ‘how’.

With regard to subject matter didactics, realism specifies that content will be drawn from certain core areas. The content of school subjects is due to Anglo-Saxon curriculum theory frequently understood as decontextualised knowledge taken from various academic disciplines that has been recontextualised as educational knowledge according to principles of transmission and acquisition. In this view, any particular ‘what’ in pedagogic practice is structured by the ‘what’ itself – ‘what’ associated with fields of knowledge production. However, we know that recontextualising processes are not a given, nor are school subjects simply reflections of academic disciplines. There are several subjects whose bases are multifaceted, and recontextualising processes can serve to integrate both regulative and instructional discourses. As a result, subject matter didactics will diverge because they are conceptualised as different. Moreover, one can assume that the more they differ, the greater the impact of particular contents. Since this difference is due to classification, subject matter didactics are horizontally related. They may be strongly classified (e.g., physics vis-a-vis arts) or weakly classified (e.g., physics relative to mathematics), but as long as there is a subject-related division of knowledge, there will be some kind of ‘segmentalism’ in subject matter didactics.

In comparing general and subject matter didactics, we are likely to find diverse recontextualising principles. The former is in some sense regulated by the ‘how’, that is, the framing of how teaching and learning are expected to manifest themselves. The latter is somewhat regulated by the ‘what’, that is, the classification of ‘what’, because the basis of subject differentiation lies in such classification, so that there is a realistic space between subject matter didactics (Bernstein, Citation2000).

Conclusion

The legitimation of educational knowledge is a problem in the sociology of education because ‘to say that some knowledge is better than others is to say that some people are better than others – to elevate the perspectives and experiences of some groups over others’ (Moore, Citation2009, p. 9). Through the lens of constructivism we are likely to reduce knowledge to knowing and reduce teaching to learning. In such cases, the didactic issue of ‘what content?’ may well be replaced by ‘whose content?’; or the ‘what’ may very well cease to exist.

If all standards and criteria are reducible to perspectives and standpoints, no grounds can be offered for teaching any one thing rather than any other (or ultimately, for teaching anything at all!). (Young, Citation2008, p. 22)

The issue of educational knowledge and its legitimacy is crucial for didactics, since teaching and learning are, by definition, dependent on educational content. Teaching implies teaching something, and learning is generally a matter of learning this (Maton, Citation2014). Consequently, curriculum and didactics must be organised on the basis of ‘objective knowledge’, that is, our best (although fallible) knowledge in the light of disciplinary foundations and proven experience (Wheelahan, Citation2010; Young & Muller, Citation2007).

By contrast to a plurality of critical approaches, social realism does not formulate objective knowledge and critical didactics as an either/or, but rather as a fruitful interaction. Social realism intends to lay bare the actual structures underlying the organisation of educational knowledge. Nevertheless, its approaches resist the reduction of knowledge and learning to expressions of those in power. In considering curriculum and didactics, the essential is not to point out that educational knowledge is socially constructed, but rather clarify how we produce and recontextualise educational knowledge – and in particular the underlying principles of curriculum and subject matter didactics. Content-based curriculum theory and content-oriented didactics will thereby have a role in investigating the social nature of knowledge, that is, the sources from which selections are made.

Social realism is closer to the Anglo-Saxon concept of curriculum than that of the German Didaktik. As a school of thought it emphasises the significance of structure and objectified knowledge, while conceptions like interpretation, understanding, meaning and subjectified Bildung are of minor concern. Both curriculum and didactic theory share a common focus on educational knowledge and content, but are distinguished by differing perspectives and even more so by different languages of description. Social realism is a theoretical platform where curriculum and didactics can meet, and where knowledge does not have to be relegated to something either internally given or externally regulated, but rather considered as complementary aspects of reality.

Notes

1 Others have also understood content as a focal point of curriculum and didactics (cf. Gundem & Hopmann, Citation1998; Hopmann & Riquarts, Citation2000). It is hoped that this article may renew the discussion of curriculum and didactics by presenting a social realist approach to educational knowledge.

2 Didaktik is used when the text refers to its continental/German tradition, while didactics is employed in all other instances.

3 Bernstein (Citation2000) conceptualises recontextualisation as a site of the pedagogic device. This device ‘provides the intrinsic grammar of pedagogic discourse’ (p. 28) and thus regulates educational policy as well as pedagogic practice. Following Maton (Citation2014), we use logics here instead of what Bernstein terms rules, avoiding the conception of the device as a deterministic system. In addition, what Bernstein calls ‘distributive rules’ are no longer framed under the field of production. Distributive logics now pervade processes within the entire device.

4 Cf. Bernstein and Lundgren, Citation1983; Lundgren, Citation1984, Citation1999.

5 cf. e.g., Hopmann, Citation1997, Citation2007; Westbury, Citation2000.

References

- Alexander J.C. Fin de siècle social theory: Relativism, reduction, and the problem of reason. 1995; London: Verso.

- Apple M.W. Creating difference: Neo-liberalism, neo-conservatism and the politics of educational reform. Educational Policy. 2004; 18(1): 12–44.

- Apple M.W. Educating the “right” way: Markets, standards, god and inequality. 2006; New York: Routledge.

- Ball S.J. Big policies/small world: An introduction to international perspectives in education policy. Comparative Education. 1998; 34(2): 119–130.

- Beck J. Makeover or takeover? The strange death of educational autonomy in neo-liberal England. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 1999; 20(2): 223–238.

- Beck J, Moore R., Arnot M., Beck J., Daniels H. ‘Directed time’: Identity and time in new right and new labour policy discourse. Knowledge, power and educational reform: Applying the sociology of Basil Bernstein. 2006; London: Routledge. 181–195.

- Bernstein B, Young M.F.D. On the classification and framing of educational knowledge. Knowledge and control: New directions for the sociology of knowledge. 1971; London: Collier-Macmillan. 47–69.

- Bernstein B. Class, codes and control. In: The structuring of pedagogic discourse, Vol. IV. 1990; London: Routledge.

- Bernstein B. Vertical and horizontal discourses: An essay. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 1999; 20(2): 157–173.

- Bernstein B. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity. Theory, research, critique, Vol. V. 2000; Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Bernstein B., Lundgren U.P. Makt, kontroll och pedagogik: Studier av den kulturella reproduktionen [Power, control and pedagogy: Studies of the cultural reproduction]. 1983; Stockholm: Liber Förlag.

- Englund T, Gundem B.B., Hopmann S. Teaching as an Offer of (Discursive?) Meaning. Didaktik and/or curriculum: An international dialogue. 1998; New York: P. Lang, cop. 215–226.

- Englund T., Forsberg E., Sundberg D, Englund T., Forsberg E., Sundberg D. Introduktion – vad räknas som kunskap?. Vad räknas som kunskap? Läroplansteoretiska utsikter och inblickar i lärarutbildning och skola. 2012; Stockholm: Liber AB. 5–17.

- Englund T., Svingby G, Marton F. Läroplansteori och didaktik. Fackdidaktik. Vol. 1. Principiella överväganden. Yrkesförberedande ämnen. 1986; Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Fairclough N. Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. 2010; (2nd ed.), Harlow: Longman Applied Linguistics.

- Forsberg E, Forsberg E. Curriculum theory revisited – introduction. Curriculum theory revisited: Studies in educational policy and educational philosophy. 2007; Uppsala: Uppsala University. 5–17. STEP Report No. 10.

- Gellner E. Postmodernism, reason and religion. 1992; London: Routledge.

- Gundem B.B., Hopmann S. Didaktik and/or curriculum: An international dialogue. 1998; New York: P. Lang, cop.

- Hopmann S, Uljens M. Wolfgang Klafki och den tyska didaktiken[Wolfgang Klafki and the German Didaktik]. 1997; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 198–214. Didaktik – teori, reflektion och praktik.

- Hopmann S. Restrained Teaching: the common core of Didaktik. European Educational Research Journal. 2007; 6(2): 109–124.

- Hopmann S., Riquarts K, Westbury I., Hopmann S., Riquarts K. Starting a dialogue: A beginning conversation between didaktik and the curriculum traditions. Teaching as a reflective practice: The German didaktik tradition. 2000; Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 3–11.

- Jank W., Meyer H, Uljens M. Didaktikens centrala frågor [chapter translated from Didaktische Modelle]. Didaktik – teori, reflektion och praktik. 1997/1991; Lund: Studentlitteratur. 47–74.

- Lindensjö B., Lundgren U.P. Utbildningsreformer och politisk styrning [Educational Reforms and Political Governance]. 2000; Stockholm: HLS Förlag/Stockholms universitets förlag.

- Lundgren U.P. Att organisera omvärlden: En introduktion till läroplansteori [Organising the world about us. An introduction to curriculum theory]. 1979; Stockholm: Liber Utbildningsförlaget.

- Lundgren U.P. Ramfaktorteorins historia [The history of ‘frame factor theory’]. Skeptron. 1984; 1(1): 69–81.

- Lundgren U.P. Ramfaktorteori och praktisk utbildningsplanering [Frame factor theory and educational planning in practice]. Pedagogisk Forskning Sverige. 1999; 4(1): 31–41.

- Maton K. Knowledge and knowers: Towards a realist sociology of education. 2014; London: Routledge.

- Maton K., Moore R, Maton K., Moore R. Coalitions of the mind. Social realism, knowledge and the sociology of education. 2010; London: Continuum. 1–13.

- Maton K., Muller J, Frances C., Martin J.R. A sociology for the transmission of knowledges. Language, knowledge and pedagogy: Functional linguistic and sociological perspectives. 2007; London: Continuum. 14–33.

- Moore R. Towards the sociology of truth. 2009; London: Continuum.

- Moore R. Basil Bernstein: The thinker and the field. 2013; London: Routledge.

- Moore R., Muller J. The discourse of “voice” and the problem of knowledge and identity in the sociology of education. British Journal of Sociology of Education. 1999; 20(2): 189–206.

- Moore R., Young M.F.D. Knowledge and the curriculum in the sociology of education: Towards a reconceptualisation’.British Journal of Sociology of Education. 2001; 20(4): 445–461.

- Muller J, Frances C., Martin J.R. On splitting hairs: Hierarchy, knowledge and the school curriculum. Language, knowledge and pedagogy: Functional linguistic and sociological perspectives. 2007; London: Continuum. 65–86.

- Westbury I, Gundem B.B., Hopmann S. Didaktik and curriculum studies. Didaktik and/or curriculum: An international dialogue. 1998; New York: P. Lang, cop. 47–78.

- Westbury I, Westbury I., Hopmann S., Riquarts K. Teaching as a reflective practice: What might didaktik teach curriculum. Teaching as a reflective practice: The German didaktik tradition. 2000; Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 15–39.

- Wheelahan L. Why knowledge matters in curriculum: A social realist argument. 2010; London: Routledge.

- Young M.F.D. The curriculum of the future. 1998; London: Routledge.

- Young M.F.D. Bringing knowledge back in: From social constructivism to social realism in the sociology of education. 2008; , London: Routledge.

- Young M.F.D., Muller J. Truth and the truthfulness in the sociology of educational knowledge. Theory and Research in Education. 2007; 5(2): 173–203.

- Young M.F.D., Muller J. Three educational scenarios for the future: Lessons from the sociology of education. European Journal of Education. 2010; 45(1): 11–27.