Abstract

This study explored the nature and effects of leadership for learning in the context of Hong Kong primary schools. Employing a mediated model of leadership for learning, the study examined how school leadership practices are perceived and shaped in the high accountability context of Hong Kong school education. Consistent with other recent empirical studies of school leadership effects, the research explored the relationship between school leadership, school-level capacity for improvement and student learning outcomes. Regression analyses found a negative impact of principal leadership practices related to strategic direction and policy environments, but a positive impact of staff management and resource management practices in terms of enhancing support for students. Contrary to expectations, schools’ capacity in supporting students had less impact on student academic outcomes than the negative impact of resources capacity and workload of teachers. Instead, mixed impact was found between principal leadership and student academic outcomes; it was negative regarding practices in strategic direction and policy environment, but positive in leader and teacher growth and development. The study refines our understanding of how the socio-cultural and organisational contexts of schools shape successful school leadership.

Over the past 20 years, education reforms have spread from country to country in a global policy infatuation with education reform. As in other parts of the world, East Asian nations have adopted a platform of education reforms with the intention of improving student learning outcomes, labour market skills and national competitiveness (Hallinger, Citation2010; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015). These reforms have included student-centred learning, accelerated schools, curriculum standards, education quality assurance, school-based management, information and communication technologies, and parental involvement (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008; Ng, Citation2010; Rahimah, Citation1998). Notably, the implementation of these policy reforms, both globally and regionally, has been scaffolded on new accountability frameworks that seek to justify increased government investments in quality education (Lee, Walker, & Chui, Citation2012; Leithwood, Citation2001; Murphy, Citation2013).

In the context of this global quest for education reform, we have also witnessed over the course of 15 years a remarkable effort to transform the primary role of the school principal from organisational managers into leaders of learning (Hallinger, Citation2003, Citation2011; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015). Although the origins of this shift can be traced to North America during the 1980s and 1990s (e.g. Cuban, Citation1988; Hallinger, Citation1992; Leithwood, Citation2001), the global discourse on ‘principals as leaders of learning’ has since penetrated most other regions of the world (e.g. Cravens & Hallinger, Citation2012; Day, Citation2009; Hallinger, Citation2011; Opdenakker & Van Damme, Citation2007). Nowhere, perhaps, has this effort to transform the focus of the principalship represented a bigger change than in East Asia (Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015).

Historically the primary roles of principals in Asia have been managerial and political in nature (Hallinger, Citation2004; Lam, Citation2003; Pan & Chen, Citation2011; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015; Walker, Hu, & Qian, Citation2012). Indeed, in most East Asian societies, the principal is formally situated in the school as an ‘officer’ of the government (Hallinger, Citation2004; Hallinger, Walker, & Gian, Citation2015; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015). However, the limitations of this role configuration in achieving education reform have gradually become apparent to policymakers. The perspectives and activities associated with a strong managerial cum political focus in the principalship are typically aimed at maintaining stability (Cuban, Citation1988; Lam, Citation2003; Hallinger, Citation1992, Citation2004), and may, therefore, be insufficient for fostering productive innovation and change in teaching and learning.

In East Asia, the response to this challenge was initially evident in a new focus on leadership preparation and development for school principals (Choy, Stout, & Tin, Citation2003; Hallinger & Lee, Citation2011; Lam, Citation2003; Lin, Citation2003; Wong, Citation2001). More recent policy initiatives have targeted the full scope of human resource management tools, from recruitment and selection to performance evaluation, in an intensifying effort to recast principals into leaders of learning (Cheung & Walker, Citation2006; Cravens & Hallinger, Citation2012; Gamage & Sooksomchitra, Citation2004; Hallinger & Lee, Citation2011; Pan & Chen, Citation2011; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015). In summary, it is no exaggeration to state that East Asia's principals are undergoing an ‘identity crisis’ as they come to terms with new role definitions, job responsibilities and performance standards.

In the face of this role transformation, we note that relatively few empirical studies have examined the practices and effects of principal leadership in East Asia (Hallinger & Lee, Citation2011; Law, Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2012; Walker & Ko, Citation2011; Yu, Leithwood, & Jantzi, Citation2002). Thus, the region's policymakers and practitioners continue to rely heavily on research findings from the global (i.e. Western) leadership literature (e.g. Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood, Day, Sammons, Harris, & Hopkins, Citation2006) when conceptualising new leadership roles and policies in East Asia. Given that scholars increasingly accept that successful leadership practices are shaped by the organisational and socio-cultural context (Hallinger & Leithwood, Citation1996; Leithwood et al., Citation2006), this suggests a need for empirical studies capable of validating global research findings in different regional settings (Dimmock & Walker, Citation1998; Hallinger & Bryant, Citation2013; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015).

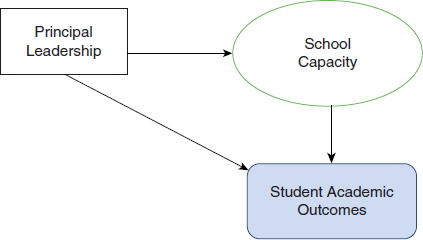

The current study sought to explore the impact of principal leadership on school capacity and student learning in 32 Hong Kong primary schools. The conceptualisation of school leadership employed in this research was guided by findings from several decades of research on school leadership effects (e.g. Bossert, Dwyer, Rowan & Lee, Citation1982; Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006; Leithwood, Patten, & Jantzi, Citation2010; Marks & Printy, Citation2003). This literature frames leadership effects on learning as mediated by a variety of school and classroom level factors and has challenged scholars to identify and elaborate on these paths (Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006, Citation2010). Consistent with this theoretical perspective, the current report addresses three research questions concerning the impact of principal leadership in the high accountability education policy context of Hong Kong.

Does principal leadership in Hong Kong primary schools have an impact on school capacity for improvement?

Does school capacity in Hong Kong primary schools have an impact on student math achievement?

What is the nature of the impact of principal leadership in Hong Kong primary schools on math achievement?

Theoretical perspectives on leadership for learning

We begin by providing an overview of how leadership for learning has been conceptualised and studied over the past several decades. Then we discuss the context in which this study took place. Finally, we present the conceptual framework.

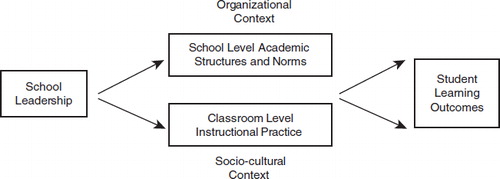

Leadership for learning in global perspective

A substantial lineage of research on instructional leadership or leadership for learning has evolved over the past 50 years (e.g. Bossert et al., Citation1982; Bridges, Citation1967; Hallinger, Citation2011; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006). The roots of this conceptualisation of principal leadership emerged in the USA during the 1950s and later experienced a growth spurt during the effective schools era of the 1980s (Bossert et al., Citation1982; Bridges, Citation1967; Hallinger, 1992, Citation2003). In the past decade, investigations into leadership for learning have increasingly accepted the proposition that these effects are achieved indirectly by influencing features of the school organisation, its cultural norms and the practices of teachers (Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006, Citation2010; Marks & Printy, Citation2003). A simplified conceptual model shown in indicates the main features of this perspective.

This conceptual model proposes that leadership effects on learning are ‘mediated’ by other features of the school. Principals do not, by themselves, produce better student outcomes (Bossert et al., Citation1982; Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006, Citation2010). Instead successful school leaders direct their efforts towards influencing intermediate targets at both the school (e.g. school climate, organisational design, capacity for improvement) and classroom levels (Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006, Citation2010).

Although the model recognises other important outcomes of education, it gives precedence to student learning outcomes as the ultimate arbiter of school success. This, in itself, represents a major change in Asia. As recently as the 1990s, in many Asian nations student learning outcomes ranked below cultural transmission and attitudes contributing to political stability in the hierarchy of national education goals (Hallinger et al., Citation2015; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015). We argue that this shift in national education goals has represented a particularly powerful ‘change force’ (Hallinger & Lee, Citation2011; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015). Moreover, as we shall discuss, over the past decade an array of policies falling under the rubric of ‘accountability and quality assurance’ have been adopted which aim to ensure that school-level practice conforms to this new goal orientation.

Finally, the conceptual model draws attention to the fact that successful school leadership must be understood (and studied) in terms of its particular context. As noted by Bossert et al. (Citation1982), schools are embedded in particular community and institutional contexts. Scholars have elaborated on this understanding of the ‘context for leadership’ by calling attention to ways that socio-cultural norms and institutional structures vary from nation to nation (Lee & Hallinger, Citation2012). Today there is consensus that the knowledge base underlying our understanding of successful school leadership must incorporate the diversity of contexts in which leadership is enacted (Hallinger & Bryant, Citation2013; Leithwood et al., Citation2006; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015).

Within this broad perspective on leadership for learning, two predominant leadership models have been theorised and investigated. These are instructional leadership (Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Hallinger & Lee, Citation2011; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010; Marks & Printy, Citation2003) and transformational leadership (Leithwood & Sun, Citation2012; Yu et al., Citation2002). Although during the 1990s these were often represented as ‘competing models’, recent research has highlighted their overlapping and complementary features (e.g. Hallinger, Citation2003; Leithwood et al., Citation2006, Citation2010; Marks & Printy, Citation2003). These include mission articulation, a focus on teacher learning and development, capacity building and creating a learning-focused instructional environment (e.g. Day, Citation2009; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006, Citation2010; Marks & Printy, Citation2003).

These perspectives shaped our approach to studying ‘leadership for learning’ in the high accountability context of Hong Kong's school system. More specifically, we examined linkages between leadership, school capacity and student learning while paying particular attention to the influence of the high accountability context that predominates in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong context for school leadership

As indicated above, an emerging global literature indicates that school leaders can positively impact student learning outcomes (Day, Citation2009; Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006). Leithwood et al. (Citation2006, Citation2010) identified a discrete set of practices (e.g. defining a clear mission) that they assert are associated with successful school leadership. However, they also concluded that the ‘enactment of these broad practices’ varies across different socio-cultural and organisational contexts. We suggest that the education accountability structures that have emerged in many parts of the world over the past two decades have reshaped the ‘institutional context’ (Bossert et al., Citation1982) in which school leadership is enacted.

School leaders sit at the nexus between policy adoption and implementation (Cuban, Citation1988). They are, at the same time, responsible for integrating education reforms into the existing platform of school practices and accountable for the school results. More than a decade ago, Leithwood foreshadowed the impact that accountability policies emerging in the UK, USA and Canada would have on school principals around the world.

This [accountability context] creates significant leadership dilemmas (Wildy and Louden, Citation2000), and school leaders attempting to respond to their governments demands for change can be excused for feeling that they are being pulled in many different directions simultaneously. They are being pulled in many different directions simultaneously. (Leithwood, Citation2001, p. 228)

Little did Leithwood know in 2001 how rapidly these accountability policies would spread across the world. Today, in East Asia, maturing education accountability frameworks are now apparent in Hong Kong (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008; Dimmock & Walker, Citation1998; Lee et al., Citation2012; Walker & Ko, Citation2011), Thailand (Gamage & Sooksomchitra, Citation2004; Hallinger & Lee, Citation2011), Taiwan (Lin, Citation2003; Pan & Chen, Citation2011), Singapore (Choy et al., Citation2003; Ng, Citation2010) and Malaysia (Rahimah, Citation1998). We need a better understanding of how school leaders lead learning within this evolving context, as well as how different sets of practices impact the school's capacity for improvement (Hallinger, Citation2003; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Leithwood et al., Citation2006).

Since the early 1990s, Hong Kong's education system has evolved in response to both local (e.g. political integration with mainland China, falling birth rates, medium of instruction requirements) and global (e.g. policy borrowing, regional integration, technological development) change forces (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008). This evolution is evident in changing system goals, policies and system structures which reflect a unique blend of Eastern and Western norms (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008; Dimmock & Walker, Citation1998; Wong, Citation2001). Entrepreneurship, market freedom and the rights of individuals have blended with proceduralism, status differentiation, hierarchical rigidity and unitary authority to shape institutional processes. Inevitably, underlying values and accompanying behavioural norms exert an influence on how principals lead in their schools (Dimmock & Walker, Citation1998; Law, Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2012; Walker & Ko, Citation2011; Wong, Citation1995, Citation2001).

The structure of Hong Kong's education system is unique even when compared with other education systems in East Asia. Specifically, there is a high level of structural decentralisation, with education services provided through School Sponsoring Bodies (SSBs) rather than a central Ministry of Education. SSBs are typically small independent organisations or foundations affiliated with Church, non-profit, or other community-based organisations. Although the Hong Kong Education Department formulates system-wide policies, SSBs have direct responsibility for providing education services (e.g. recruiting, hiring and firing principals and teachers).

With its background as an island city-state, Hong Kong has traditionally placed great stock on enhancing competitiveness through world-class education (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008). This is reflected in the obsession among local media and policymakers with PISA results, World University Rankings and policy trends emerging in developed Western societies. Although local political leaders increasingly look towards Beijing for guidance on internal issues, there remains a strong tendency to benchmark educational standards against those of the UK.

Demands for efficiency, effectiveness and continuous improvement were given new impetus by the formal adoption of a School Based Management policy framework in 2003. This framework built upon a voluntary, decade-long effort to implement school-based management in Hong Kong (Wong, Citation2001). The new framework consolidated the decentralised system structure with formalised, mandatory procedures focused on enhancing educational quality assurance and accountability (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008). This has resulted in myriad new systems of reporting and documentation using centrally determined performance indicators (Lee et al., Citation2012; Walker & Ko, Citation2011). A decade hence, there are territory-wide benchmarking tests for both teachers and students, as well as a system of periodic ‘school inspections’.

Scholars (e.g. Caldwell & Spinks, Citation1988) initially proposed school-based management as a structural means of giving greater autonomy and control to schools over the means of producing quality education outcomes (e.g. governance, budget, staffing). Yet, Hong Kong's version of SBM has largely replaced the relatively flat, loosely-coupled structures of the past with a more tightly-coupled, vertical hierarchy designed to give the Education Department greater control over schools.

Not surprisingly, this bears similarities to the UK where Ball described a similar policy trend.

The act of teaching and the subjectivity of the teacher are both profoundly changed within the new management panopticism (of quality and excellence) and the new forms of entrepreneurial control (through marketing and competition). (Ball, Citation2003, p. 219)

This would aptly describe Hong Kong as well, where policy levers not only encompass quality, excellence and accountability but also market competition among schools for students. A combination of centralised funding formulas and declining student enrolments have introduced a high degree of inter-school competition for students. Moreover, centrally collected information is converted into performance indicators that are subsequently used for classifying schools and producing league tables (Ball, Citation2003). In the market-driven context of Hong Kong, publication of this information can be critical to a school's (or principal's) survival.

Market forces and the system's accountability framework have ratcheted up pressure on principals and schools to perform according to increasingly narrow indicators (Walker & Ko, Citation2011). Accountability and quality assurance systems leave few education processes uninspected. In the context of declining enrolment and school closures, the combined impact of accountability systems and market competition for students are an ever-present sword of Damocles hanging over the door of the principal's office. Thus, in Hong Kong, principals find themselves accountable to their SSBs, the Education Department and the student marketplace. Like their counterparts in other developed societies, school leaders in Hong Kong have to shoulder the burden of interpreting and enacting a raft of education reforms aimed at school improvement in the context of these new accountability frameworks.

Conceptual framework for this study

The conceptual framework shown in represents our operationalisation of the broader framework presented in . This conceptual model attempts to capture the relationships among a broad set of variables: accountability contexts, leadership practices, school capacity and student academic outcomes. There were no direct measures for the accountability contexts. Instead, we seek to infer the influence of the accountability context indirectly through interpretation of selected leadership dimensions (Walker & Ko, Citation2011).

Fig. 2. Conceptual model of principal leadership, school capacity and student academic outcomes in an accountability context.

The study examines seven dimensions of leadership practice. These include Strategic Direction and Policy Environment; Quality Assurance and Accountability; Teaching, Learning and Curriculum; Leader and Teacher Growth and Development; Staff Management; Resource Management; and External Communication and Connection. Our selection of these seven dimensions reflects conceptualisations of school leadership employed in other recent studies conducted in England, the USA, Canada and Australia (e.g. Day, Citation2009; Hallinger, Citation2003; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010; Lee et al., Citation2012; Leithwood et al., Citation2010; Walker & Ko, Citation2011).

Notably, the seven dimensions incorporate key aspects of both instructional leadership and transformational leadership (Hallinger, Citation2003; Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Leithwood et al., Citation2010; Leithwood & Sun, Citation2012). In addition, however, we also include dimensions that more explicitly incorporate important features of leading schools in Hong Kong (e.g. Strategic Direction, Resource Management, Quality Assurance and Accountability). This seven-dimension framework had been validated in a recent study of leadership and school improvement in Hong Kong secondary schools (Walker & Ko, Citation2011). Although school capacity has been studied (Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010), there is no consensus over its operational definition. Accordingly, we decided to employ the definition previously used by Walker and Ko (Citation2011) in their research conducted in Hong Kong (see also Lee et al., Citation2012).

Method

This paper reports findings from the first year of a 2-year longitudinal survey study of 32 primary schools in Hong Kong. The research design is similar to that employed in the main body of studies that have employed a mediated effects model of school leadership effects (e.g. Marks & Printy, Citation2003; Hallinger & Heck, Citation1996; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010, Citation2014; Marks & Printy, Citation2003; Thoonen, Sleegers, Oorta, & Peetsmaa, Citation2012). A post hoc analysis aimed at exploring the relationship of leadership with a of variety school conditions and student learning.

Respondents

We sought participation in this study from schools located in four of Hong Kong's larger SSBs (i.e. similar to local educational authorities). In total, 32 schools agreed to participate in the study. An analysis of the school profiles indicated that despite this being a convenience sample, the distribution was not biased in terms of location in Hong Kong or the socio-economic background of students. In total, 411 Key Staff (i.e. middle level leaders) completed the online questionnaire, with a response rate 78%. A breakdown of the sample of individual schools is shown in Table .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations for leadership dimensions and support for students.

In Hong Kong, middle level leaders are commonly referred to as ‘Key Staff. As local primary school teachers are predominantly female, 74% of the Key Staff in the sample were also female. Key Staff were represented by professional teaching staff holding academic or functional duties such as Vice-principal (7.2%), Functional Department Head (41.5%) and Panel Head (51.3%). Demographic information included in the survey included age highest education qualification, years of teaching in the present school, and years in their current role in the school. Analysis of the Key Staff profile suggests that these respondents were not only highly experienced, but had also maintained reasonably long tenure in their current schools (not tabled).

Within these 32 schools 2,924 students completed the Math test. Analyses indicated that inclusion or deletion of the survey data of the two schools doing the non-P4 Math test did not affect the overall survey results. Since a larger sample was preferred, we used the additional two schools in analyses of the general perceptions of principal leadership.

Instruments

The data were collected from an online survey and an Math test for Primary Level 4 students. These were piloted in June, 2011 with four schools. Then the survey was administered through an online system in 32 schools between November, 2011 and January, 2012. The math test was administered concurrent with the teacher survey.

Survey

A Chinese language questionnaire was used to collect perceptions of Key Staff on the leadership practices of their principals and a variety of school conditions that are proposed to impact teaching and learning in schools. Although the instrument had been validated in a previous study of Hong Kong secondary schools (Walker & Ko, Citation2011), we revalidated the scale in the current study. The instrument demonstrated high overall scale reliability with alpha coefficients ranging from 0.72 to 0.99 on the various subscales.

The instrument included 33 items to measure seven dimensions of principal leadership. Each item in this instrument described the principal’s leadership practice on which the respondents were asked to rate on a 6-point forced-choice Likert scale. The choices focused on identifying the extent to which, and whether their actions had led to change in the school over the past 3 years (varying from very significantly to not at all).

The scales measuring school capacity were based on scales originally developed by Leithwood and colleagues. The 33 items in this scale covered seven aspects of school capacity. These included Trust among Teachers, Communication among Staff, Alignment, Coherence, and Structure, Professional Learning among Teachers, Workload of Teachers, Resource Capacity of the School, and Support for Students. Respondents were asked to use a 6-point forced-choice Likert scale, to indicate the magnitude (i.e. slightly, moderately, and strongly) of their agreement or disagreement of the statements characterising their schools.

Of these 33 items, four measured the school capacity in Support for Students:

The atmosphere throughout our school encourages students to learn;

Our school provides after-school academic support activities for students;

Teachers have access to the teaching resources that they need to do a good job; and,

Our school provides a broad range of extracurricular activities for students.

Math test

The online Math test was a crucial feature in this study because we needed a reliable assessment of student academic outcomes. However, standardised testing was not available as in the UK or the USA. Our test items were originally developed by another research team in our institute for the local government when introducing standardised testing in primary schools in Hong Kong. Thus, all test items were Rasch calibrated with the Hong Kong norm for Primary Level 4 students.

Data collection

All data were collected online through two different e-platforms set up with the assistance of a local e-publisher. The Math test was administered online in each school's computer lab under the supervision of the Math class teacher. The e-platform was set up with a unique login code for each student. The system would generate the student's name after logging in to ensure accuracy in identification. The system generated error messages and highlighted questions without answers to ensure that all questions were answered before final submission. With these methods, we achieved a response rate over 99%. Analyses of the Math tests were performed using Winsteps (Linacre, Citation2009). Although brief demographic information was collected, the teacher surveys were anonymous. Since a respondent was required to give a response to all items in a section before proceeding to another section, there were no missing data.

Data analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted for the leadership and school capacity scales. We used LISREL 8.8 with factors allowed to freely correlate. Reliability tests was run to test the internal consistency of the scales. Fit of the leadership model and the school capacity model was assessed using Chi-square, the root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its associated confidence interval, together with the non-normed fit index (NNFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Relative Fit Index (RFI) and the squared root mean residual (SRMR). The multiple indices indicated an acceptable level of validity for the survey instrument (see also Walker & Ko, Citation2011).

We used a three-step hierarchical multiple regression analysis to explore the relationship between the seven dimensions of leadership practices and the school capacity variable, Support for Students, and on student academic outcomes in the Math test. Employing hierarchical multiple regression allowed us to test more hypotheses than simple multiple regression. In each step, we were able to test the relative significance of the selected variables. For measuring the relative impact of the seven school capacity variables, multiple regression analysis was initially performed using the Enter Method and then the Stepwise Method.

Results

Our analyses aimed at exploring how school leadership practices impact school capacity and student achievement. The preliminary analyses focus on understanding how Key Staff perceived their schools' leadership. Then we examine data that pertain to each of the three research questions.

Perceptions of principal leadership practices and school support for students

Perceptions of principal leadership practices and school capacity were examined with confirmatory factor analysis. For the leadership data, the seven-dimension model of Leadership produced moderately satisfactory goodness-of-fit indices (χ 2=1789.95, df=474, p=0.00; RMSEA=0.082 with 90% CI=0.078, 0.086 and p-value for Close Fit=0.00; NNFI=0.98; CFI=0.099; IFI=0.99; RFI=0.98; SRMR=0.048). The factor loadings of the Leadership items were generally high, with all 33 items loading at or above 0.74. Reliability tests indicated strong internal consistency for the Leadership scale. Cronbach's alphas ranged from 0.84 to 0.87 on the subscales.

For the school capacity data, confirmatory factor analysis was performed on both the full model as well as on the single factor, Support for Students. The multi-factor model produced marginally acceptable goodness-of-fit indices: (χ 2=1675.55, df=356, p=0.00; RMSEA=0.095 with 90% CI=0.091, 0.01 and p-value for Close Fit=0.00; NNFI=0.94; CFI=0.095; IFI=0.95; RFI=0.93; SRMR=0.097). Model specification for the subscale, Support for Students demonstrated excellent fit indices when the errors of two items, ‘Our school provides after-school academic support activities for students’ and ‘Teachers have access to the teaching resource that they need to do a good job’ were set to be correlated (χ 2=0.18, df=1, p=0.67; RMSEA=0.00 with 90% CI=0.0, 0.099 and p-value for Close Fit=0.79; NNFI=1.01; CFI=1.00; IFI=1.00; RFI=1.00; SRMR=0.047). The factor loadings of the items for Support for Students ranged between 0.55 and 0.78. Internal consistency of Support for Students yielded a Cronbach's alpha of 0.72 indicating acceptable reliability.

Means and standard deviations of the Leadership dimensions and Support for Students were computed by averaging the item scores of each factor. These mean scores were used in subsequent regression analyses (See Table ). The mean scores showed low variability across the Leadership dimensions (see Table ). In contrast, however, the mean (i.e. 4.57) for Support for Students was higher than those of Leadership dimensions, with a lower standard deviation (0.67). These results indicated teachers generally rated their schools’ Support for Students more positively and consistently than their principal's leadership.

All correlation pairs except the one between Strategic Direction and Policy Environment and Support for Students were significant at p<0.01. The inter-correlations among the Leadership dimensions were generally high, ranging from r=0.67 to r=0.89. As for Support for Students, the correlations with Leadership dimensions were rather low, mainly between r=0.04 and r=0.30. In general, Support for Students showed statistically significant but weak connections with Leadership dimensions.

The connection between schools’ Support for Students and the leadership dimension Strategic Direction and Policy Environment was statistically insignificant (r=0.04), though it was assumed to be crucial in the accountability context. The inter-correlation between Support for Students and the dimension Quality Assurance and Accountability was statistically significant but weak (r=0.23). Connections with Support for Students were strongest with two Leadership dimensions: Staff Management (r=0.30) and Resource Management (r=0.29). Thus, the relationship between Leadership and Support for Students was weaker than expected.

Impact of principal leadership on school support for students

To further explore the impact of Leadership on Support for Students, hierarchical multiple regression was conducted in three steps. In the first step, only Strategic Direction and Policy Environment and Quality Assurance and Accountability were used as predictors. We assumed that these two Leadership dimensions would be especially influential in a high accountability education policy context.

Although, as expected, the impact of the impact of Quality Assurance and Accountability was moderately positive (b=0.401), the impact of Strategic Direction and Policy Environment was actually negative (b=−0.243). The total variance explained (see Table ) indicated that the impact of Quality Assurance and Accountability (7.85%) was more than twice that of Strategic Direction and Policy Environment (3.03%). These results indicated that principals who were rated highly in their practices associated with Strategic Direction and Policy Environment tended to be in schools that were perceived as weaker in the Support for Students.

Table II. Relative impact of leadership practices on support for students by Key Staff and general teachers.

Two more Leadership dimensions, Teaching, Learning and Curriculum and Leader and Teacher Growth and Development, were added into the model in the second step. While the impact of Strategic Direction and Policy Environment remained negative and even strengthened (b=−0.399; total variance explained, 5.48%), the previous significant impact of Quality Assurance and Accountability disappeared and was partially taken up by the dimension Leader and Teacher Growth and Development (i.e. b=0.243; total variance explained, 1.71%).

When all Leadership dimensions were added into the model in the final step, the impact of Leader and Teacher Grown and Development dissipated. The negative and dominant impact of Strategic Direction and Policy Environment (b=−0.394; total variance explained, 5.63%) was counteracted by a positive impact of Staff Management (b=0.284; total variance explained, 2.26%) and Resource Management (b=270; total variance explained, 1.77%). The hierarchical regression results were partially consistent with the bivariate correlations in Table . The final model was significant [F(6, 404)=12.914, p=0.001], but with a small adjusted R-Square (0.148). This suggests that in the end, Leadership practices did not act as strong predictors of Support for Students in these schools.

In summary, the regression results did not confirm our predictions regarding the impact of Leadership on Support for Students. Although the impact of Strategic Direction and Policy Environment on Support for Students was confirmed, the relationship was not strong as we had expected. Moreover, surprisingly, the dimensions associated with instructional leadership (i.e. Quality Assurance and Accountability; Teaching, Learning and Curriculum) had little impact on Support for Students, while Resource Management and Staff Management did. This pattern of results suggests that, in general, teachers did not perceive their principals as strong instructional leaders, and that these related Leadership dimensions did not impact Support for Students. Instead, teachers perceived the principals as focusing more on the management of physical and human resources. Also surprisingly, teachers who rated their principals higher on Strategic Direction and Policy Environment tended to rate their schools’ as weaker on Support for Students.

Impact of school capacity on student learning

As discussed earlier, the model of school capacity used in this study was based on a seven-factor model with particular focus on the subscale, Support for Students (see Table ). Capacity and Workload were the strongest predictors, but their impact on Math test results was negative (β=−0.141 and −0.147, respectively for the Enter Regression method; β=−0.146 and −0.154, respectively for the Stepwise method). There was a positive impact for Trust (β=0.124) among teachers when the Stepwise method was used. The regression model based on three predictors was significant [F(3,372)=4.949, p<0.05], but yielded a very low explanatory power (Adjusted R 2=0.031). The variance explained for the individual predictors only accounted for 1.4−2.1% of the variance.

Table III Multiple regression analysis results on various school capacity on Student Academic Outcomes (N=376; Key Staff of P4 schools).

The hypothesised impact of Support for Students on Math achievement was statistically insignificant. It might be puzzling to find that schools in which teachers perceived better resource capacity and workload had weaker academic performance. However, this finding was consistent with the author's research in some Hong Kong secondary schools (Lee et al., Citation2012; Walker & Ko, Citation2011). Specifically, in Hong Kong secondary schools resource capacity and workload were neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for schools with respect to attainment of higher value-added results in student learning. The overall results regarding school capacity in this primary school sample suggested there was limited effect of Support for Students on Math test results.

Impact of principal leadership on student math achievement

Table shows the results of only two of the steps planned for the hierarchical regression analysis, because the Leadership dimensions in the last step contributed little to improve the prediction. When Strategic Direction and Policy Environment and Quality Assurance and Accountability were used as predictors in the first step, only the former showed a significant relationship. Notably, the effect was again negative (β=−0.157), but accounted for only 1.28% of variance. Strategic Direction and Policy Environment and Leader and Teacher Growth and Development were significant predictors in the second step, but the model yielded low explanatory power [adjusted R 2=0.027. F(4, 371)=3.634, p<0.01], and contributed to only a small portion of the variance explained (i.e. 1.91 and 1.09%, respectively).

Table IV Hierarchical regression results of principal leadership impact on math results (N=376, Key Staff).

Moreover, their impact was again found to be opposite to the expected direction. As in the earlier regression results, the impact of Strategic Direction and Policy Environment was negative, while Leader and Teacher Growth and Development was positive. The results indicate that principals who were rated highly on Strategic Direction and Policy Environment were more likely to have more students with lower performance on the Math test.

Discussion

Over a decade ago, Leithwood (Citation2001) called for further research on ‘leadership practices that help improve education for students while, at the same time, acknowledging the legitimate demands of policy makers to have their initiatives authentically reflected in the work of the school’ (Leithwood, Citation2001, p. 230). This was a prescient anticipation of how the changing accountability context in education systems would reshape the context for school leadership around the world (e.g. Cheng & Walker, Citation2008; Walker & Ko, Citation2011).

Our study contributes to an emerging generation of research on school leadership in East Asia in general (Hallinger & Lee, Citation2011; Hallinger et al., Citation2015; Lin, Citation2003; Ng, Citation2010; Pan & Chen, Citation2011; Rahimah, Citation1998; Walker & Hallinger, Citation2015), and Hong Kong in particular (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008; Cheung & Walker, Citation2006; Hallinger, Ko, & Walker, Citation2014; Law, Citation2011; Lee et al., Citation2012; Walker & Ko, Citation2011; Yu et al., Citation2002). The latter body of empirical research has begun to provide a benchmark against which to assess the extent to which Hong Kong's evolving accountability framework is achieving the desired goals of improved staff capacity and student learning results. In this final section of the paper, we review limitations of the study, interpret the meaning of the results and identify implications of the findings.

Limitations of the study

Despite the large sample sizes obtained for both teachers and students, this study employed a convenience sample of only 32 Hong Kong primary schools. Although our inspection of the school and staff profiles did not reveal any bias we, acknowledge that our findings should be accepted as preliminary and in need of additional verification.

In addition, as noted earlier, Hong Kong's institutional structures have evolved along a rather different path from other East Asian education systems. Therefore, although we suggest that the Hong Kong accountability context offers a useful backdrop against which to study school leadership, we do not claim that our findings would be replicated in neighbouring societies.

Interpretation of the findings

In reflecting on the pattern of results obtained in this study, we suggest that principals are facing significant dilemmas in reconciling conflicting pressures in Hong Kong's high accountability context (Cheung & Walker, Citation2006; Lee et al., Citation2012; Leithwood, Citation2001; Wildy & Louden, Citation2000). This was apparent both in the negative effects of Strategic Direction and Policy Environment on the dependent variables included in this study, as well as in the lack of positive effects of instructional leadership. Notably, the negative effects of Strategic Direction and Policy Environment were so persistent that they did not disappear when other leadership dimensions were added to the hierarchical regression model (see also Scheerens, Citation2012).

The findings suggest that the principals in these Hong Kong primary schools are finding it difficult to manage expectations from above and below (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008; Cheung & Walker, Citation2006; Cuban, Citation1988; Lam, Citation2003). Strong pressure from bureaucratic and market channels have ratcheted up externally-imposed accountability for school learning outcomes. A raft of system-level policies requires principals to engage in a complex, array of ‘quality processes’ that shape their leadership practices.

Simultaneously, professionally-oriented policy reforms implemented over the past decade have yielded a new framework for pre-service and in-service preparation and development for teachers and school leaders. A related policy reform even inserted a new ‘curriculum leader’ role within Hong Kong primary schools. The intention of this policy was to support overloaded principals in leading learning. Other policies have sought to professionalise teaching and foster organisational learning by encouraging development of ‘professional learning communities’. The pattern of results in this and related studies (e.g. Lee et al., Citation2012; Hallinger et al., Citation2014; Walker & Ko, Citation2011) call into question whether these policies are achieving the desired effect of building school capacity for improvement.

Principals appear to be focused on survival and compliance (Cheng & Walker, Citation2008; Cheung & Walker, Citation2006) more so than proactive support for teaching and learning (see also Lee et al., Citation2012). Notably, our findings are consistent with Walker and Ko's (Citation2011) conclusion from their study of Hong Kong secondary schools. ‘The job of the principal then is to massage school conditions and build the capacity of staff so that they can work successfully to mission achievement and meet central requirements’ (Walker & Ko, Citation2011, p. 385).

Implications

We close by highlighting several implications. First, the finding that teachers perceive relatively weak leadership from their principals complements other recent findings in Asia (e.g. Hallinger & Lee, Citation2011; Hallinger et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2012; Walker & Ko, Citation2011). We frame this as an ‘identity transition dilemma’. Asia's principals have traditionally adopted a managerial cum political role in leading their schools. Policy-imposed pressure to focus more centrally on practices associated with instructional and transformational leadership is yet to be revealed in studies of principal practice in Hong Kong and other parts of the region. This was reflected in the pattern of results related to instructional leadership vs. staff and resource management dimensions of the leadership model.

We suggest that in Hong Kong the introduction of accountability systems has reinforced socio-cultural tendencies towards proceduralism and hierarchy among the principals. Principals are focusing on meeting procedural requirements which tend to be clearer and more specific than exhortations to develop ‘professional learning communities’. Instead of engaging their role as instructional leaders more proactively, they are engaged in a struggle for compliance with system requirements and survival in a competitive market environment.

A general lack of leadership impact for Teaching, Learning and Curriculum on school capacity and math achievement has implications for the broader global discourse on the nature of successful school leadership (see Scheerens, Citation2012). Our data suggests that in the absence of instructionally-focused leadership, the effects of transformational leadership (i.e. dimensions aimed at broader capacity building) are diffused. Thus, consistent with other scholars (e.g. Hallinger, Citation2003; Leithwood et al., Citation2010; Marks & Printy, Citation2003; Murphy, Citation2013), we suggest that successful school leadership should include an instructional- or learning-oriented focus. However, the extent to which this is possible in the current environment remains an open question.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Joanna Li, Rebecca Li and Bowie Liu for their assistance in data collection and Wayne Chen for his assistance in data analysis. This study was supported in part by funding support from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong through the General Research Fund Project # 840509.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Philip Hallinger

Dr. Philip Hallinger is Professor of Education Management at Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, and a Distinguished Visiting Professor at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

James Ko

Dr. James Ko is Assistant Professor of Educational Policy and Leadership in the Hong Kong Institute of Education.

References

- Ball S. The teacher's soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy. 2003; 18(2): 215–228.

- Bossert S., Dwyer D., Rowan B., Lee G. The instructional management role of the principal. Educational Administration Quarterly. 1982; 18(3): 34–64.

- Bridges E. Instructional leadership: A concept re-examined. Journal of Educational Administration. 1967; 5(2): 136–147.

- Caldwell B., Spinks J. The self-managing school. 1988; Philadelphia, PA: Falmer Press.

- Cheng Y.C., Walker A. When reform hits reality: The bottleneck effect in Hong Kong primary schools. School Leadership and Management. 2008; 28(5): 505–521.

- Cheung R.M.B., Walker A. Inner worlds and outer limits: The formation of beginning school principals in Hong Kong. Journal of Educational Administration. 2006; 44(4): 389–407.

- Choy K.C., Stott K., Tin G.T, Hallinger P. Developing Singapore school leaders for a learning nation. Reshaping the landscape of school leadership development: A global perspective. 2003; Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. 163–174.

- Cravens X.C., Hallinger P. School leadership and change in the Asia-Pacific region: Building capacity for reform implementation. Peabody Journal of Education. 2012; 87(2): 1–10.

- Cuban L. The managerial imperative and the practice of leadership in schools. 1988; Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Day C, Harris A. Capacity building through layered leadership: Sustaining the turnaround. Distributed leadership. 2009; Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Dimmock C., Walker A.D. Transforming Hong Kong's schools: Trends and emerging issues. Journal of Educational Administration. 1998; 36(5): 476–491.

- Gamage D., Sooksomchitra P. Decentralization and school based management in Thailand. International Review of Education. 2004; 50: 289–305.

- Hallinger P. Changing norms of principal leadership in the United States. Journal of Educational Administration. 1992; 30(3): 35–48.

- Hallinger P. Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Educational Administration. 2011; 49(2): 125–142.

- Hallinger P. Leading educational change: Reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education. 2003; 33(3): 329–351.

- Hallinger P. Making education reform happen: Is there an “Asian” way?. School Leadership and Management. 2010; 30(5): 401–408.

- Hallinger P. Meeting the challenges of cultural leadership: The changing role of principals in Thailand. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. 2004; 25(1): 61–73.

- Hallinger P., Bryant D.A. Mapping the terrain of research on educational leadership and management in East Asia. Journal of Educational Administration. 2013; 51(5): 618–637.

- Hallinger P., Heck R.H. Reassessing the principal's role in school effectiveness: A review of empirical research, 1980–1995. Educational Administration Quarterly. 1996; 32(1): 5–44.

- Hallinger P., Ko J., Walker A. Exploring whole school vs. subject department improvement in Hong Kong secondary schools. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2014; 26(2):215–239. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.882848.

- Hallinger P., Lee M.S. Assessing a decade of education reform in Thailand: Broken promise or impossible dream?. Cambridge Journal of Education. 2011; 41(2): 139–158.

- Hallinger P., Leithwood K. Culture and educational administration: A case of finding out what you don’t know you don’t know. Journal of Educational Administration. 1996; 34(5): 98–115.

- Hallinger P., Walker A., Gian T. T. Making sense of images of fact and fiction: A critical review of research on educational leadership and management in Vietnam. Journal of Educational Administration. 2015; 53(4): 445–466.

- Heck R.H., Hallinger P. Collaborative leadership effects on school improvement: Integrating unidirectional- and reciprocal-effects models. The Elementary School Journal. 2010; 111(2): 226–252.

- Heck R.H., Hallinger P. Modeling the effects of school leadership on teaching and learning over time. Journal of Educational Administration. 2014; 52(5): 653–681.

- Lam Y.L.J, Hallinger P. Balancing stability and change: Implications for professional preparation and development of principals in Hong Kong. Reshaping the landscape of school leadership development: A global perspective. 2003; Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. 175–188.

- Law E.H.F. Exploring the role of leadership in facilitating teacher learning in Hong Kong. School Leadership & Management. 2011; 31(4): 393–410.

- Lee M.S., Walker A., Chui Y.L. Contrasting effects of instructional leadership practices on student learning in a high accountability context. Journal of Educational Administration. 2012; 50(5): 586–611.

- Leithwood K. School leadership in the context of accountability policies. International Journal of Leadership in Education. 2001; 4(3): 217–235.

- Leithwood K., Day C., Sammons P., Harris A., Hopkins D. Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. 2006; Nottingham, UK: National College of School Leadership.

- Leithwood K., Patten S., Jantzi D. Testing a conception of how school leadership influences student learning. Educational Administration Quarterly. 2010; 46(5): 671–706.

- Leithwood K., Sun J.P. The nature and effects of transformational school leadership: A meta-analytic review of unpublished research. Educational Administration Quarterly. 2012; 48(3): 387–423.

- Lin M.D, Hallinger P. Professional development for principals in Taiwan: The status quo and future needs. Reshaping the landscape of school leadership development: A global perspective. 2003; Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger. 205–216.

- Linacre J.M. Winsteps®(Version 3.69). 2009; Beaverton, OR: Winsteps.com.

- Marks H., Printy S. Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly. 2003; 39(3): 370–397.

- Murphy J. The architecture of school improvement. Journal of Educational Administration. 2013; 51(2): 252–263.

- Ng P.T. The evolution and nature of school accountability in the Singapore education system. Educational Assessment. Evaluation and Accountability. 2010; 22(4): 275–292.

- Opdenakker M., Van Damme J. Do school context, student composition and school leadership affect school practice and outcomes in secondary education?. British Educational Research Journal. 2007; 33(2): 179–206.

- Pan H.L., Chen P.Y. Challenges and research agenda of school leadership in Taiwan. School Leadership & Management. 2011; 31(4): 339–353.

- Rahimah H.A. Educational development and reformation in Malaysia: Past, present and future. Journal of Educational Administration. 1998; 36(5): 462–475.

- Scheerens J. School leadership effects revisited. 2012; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

- Thoonen E., Sleegers P., Oorta F., Peetsmaa T. Building school-wide capacity for improvement: The role of leadership, school organizational conditions, and teacher factors. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2012; 23(4): 441–460.

- Walker A., Hallinger P. Synthesis of reviews of research on principal leadership in East Asia. Journal of Educational Administration. 2015; 53(4): 467–491.

- Walker A., Ko J. Principal leadership in an era of accountability: A perspective from the Hong Kong context. School Leadership and Management. 2011; 31(4): 369–392.

- Walker A.D., Hu R.K., Qian H. Principal leadership in China: An initial review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. 2012; 23(4): 369–399.

- Wildy H., Louden W. School restructuring and the dilemmas of principals work. Educational Management Administration Leadership. 2000; 28(2): 173–184.

- Wong K.C. Education accountability in Hong Kong: Lessons from the school management initiative. International Journal of Educational Research. 1995; 23(6): 519–529.

- Wong K.C. Chinese culture and leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education. 2001; 4(4): 309–319.

- Yu H., Leithwood K., Jantzi D. The effects of transformational leadership on teachers’ commitment to change in Hong Kong. Journal of Educational Administration. 2002; 40(4): 368–389.