Abstract

This paper presents knowledge about learning-oriented leadership as part of managers’ daily work. The aim is to contribute findings from an empirical study in the software communication industry and discuss their potential contribution to leadership in the school context. Through an empirical and learning-theory-based analysis of managerial acts of influence, learning-oriented leadership is suggested as an analytical concept. In the educational leadership literature concerning instructional, pedagogic or learner-centred leadership, the interpretation of each concept is shifting and thus unstable. The studying of a non-school empirical context contributes to an analytical separation of the pedagogical leadership task from the pedagogical core task, which may be useful when returning to the school context. The learning-oriented categorisation of managerial acts of influence presents different routes for managers – including school principals – to intervene in their employees’ learning and competence on both individual and collective levels. Here, we offer an alternative suggestion for how to understand what principals do to influence the work in their organisations.

Nowadays, in organisations, learning and competence issues have become intertwined with both the task responsibilities of managers and strategic-level agendas. Sandberg and Targama (Citation2007) identify such priorities in management practice and describe it as a necessity for managers to develop a ‘more important pedagogical role’ (p. 9). This is in addition to the overall increase in the amount of evidence of the importance of workplace learning for organisational performance and success (Cedefop, Citation2011). When workplace learning is regarded as key to organisational performance, knowledge is required both about how people learn and about how to influence and advance such learning – this is also the case in school organisations.

As organisation researchers outside the school setting, we find that pedagogical leadership in the school context is contaminated with the fact that pedagogy is the core activity of a school organisation. In addition, Harris (Citation2004, Citation2007) states that the school leadership field is ‘replete with different labels of leadership’ (Harris, Citation2007, p. 315) that apply ‘to the same conceptual terrain’ (Harris, Citation2004, p. 12), such as instructional leadership, pedagogical leadership and learner-centred leadership. There is a problem in separating these terms from each other, which in turn means that recent integration trials are unlikely to succeed (Harris, Citation2007). A similar problem exists in the Swedish national context, where the label ‘pedagogical leadership’ has a lengthy history and is criticised as being a piece of national-level political rhetoric that lacks a scientific ground (Nestor, Citation2006). Furthermore, Neumerski (Citation2012) concludes, ‘We lack an understanding of what happens inside the conditions for learning and improvement. How do leaders interact with one another, with teachers, and with particular contexts to create learning?’ (ibid. p. 334). This paper does not add to the number of labels but offers the analytical concept of learning-oriented leadership, which is based on learning theory and was empirically developed outside the school context – a context in which work tasks are not normatively dictated by a political agenda, as is the case for schools.

The aim of this paper is to contribute findings from an empirical study about learning-oriented leadership in the software communication industry (Döös, Johansson, & Wilhelmson, 2015a) and discuss their potential contribution to leadership in the school context. From a learning theoretical perspective, the paper analyses managerial acts of influence as learning-oriented leadership and suggests that knowledge obtained from managers in the context of software communication may also be relevant in schools. The paper presents categories of learning-oriented leadership that emerge as part of managers’ daily work. It also points to the importance of studying how conditions for learning processes may be created when there is no explicit aim to facilitate learning and that can occur beyond direct managerial interaction (Döös et al., Citation2015a). In discussing this knowledge as being potentially relevant to leadership in schools, our focus is on schools as organisations (Larsson, Citation2004; Larsson & Löwstedt, Citation2007), and our theoretical basis holds work-integrated learning to be the genesis process behind competence (e.g. Döös, Citation2007; Ellström, Citation2001). The paper's contribution aligns with the requirement, according to Hoy and Miskel (Citation2008), of more empirical studies related to theoretical points of departure about learning.

Previous research about managers’ facilitation of learning is introduced. The learning theoretical point of departure used in the empirical analysis is then explained, as well as the methods. In the findings section, we present the categories of learning-oriented leadership that were identified in our software communication case study. Finally, we discuss learning-oriented leadership and suggest that it is a potentially valuable analytical concept in the school context. In relation to the school context, the paper relies on the principle of case-to-case generalisation, which, according to Firestone (Citation1993), passes the responsibility for the application of the results from the researcher to the reader.

Previous research

In the following section, we give a brief introduction of previous studies about managers’ facilitation of learning outside the school setting. There is a gap in this body of literature, as few studies deal with how to lead learning through the acts of influence of managers that emerge in their daily work and with the creation of learning conditions beyond face-to-face interaction. We briefly mention the literature on international school leadership, where we find a conceptual terrain with a normative interest in discussing concepts such as instructional, pedagogical and learning-centred leadership.

Managers’ facilitation of learning

In the literature about learning in organisations, we have, during the last decade, seen an increased emphasis on creating opportunities for learning through the development of the workplace as a learning environment (e.g. Billett, Citation2004; Illeris, Citation2004; Johansson, Citation2011). In discussing workplaces as learning environments, Ellström (Citation2011) differentiates among working environments that constrain or enable learning. Previous research also points to the importance of leadership in relation to the development of organisational learning (Yukl, Citation2009) and learning-enabling workplaces (e.g. Agashae & Bratton, Citation2001; Amy, Citation2008). Outside the school setting, previous research has enhanced the knowledge about learning-committed leadership (Ellinger, Citation2005) and attempts to intentionally influence both learning (e.g. Doornbos, Bolhuis, & Simons, Citation2004; Ellinger & Bostrom, Citation2002; Noer, Citation2005) and personal competence (Bredin & Söderlund, Citation2007) – often with the focus on face-to-face communication and with the manager as an interaction partner (Koopmans, Doornbos, & van Eekelen, Citation2006). The lion's share of this research is based within the human resources (HR) tradition of managerial facilitation of learning. The emphasis on informal learning in the HR literature is shared by studies in the literature on adult learning and workplace learning (Ellström, Citation2010). In this vein, both Wallo (Citation2008) and Warhurst (Citation2013) develop an understanding about leadership in relation to learning that is based on managers’ beliefs about learning and their thinking about how to enable it. Furthermore, positive as well as negative organisational contextual factors have been identified (Ellinger & Cseh, Citation2007). On the positive side, there are two themes: learning-committed leadership/management and an internal culture committed to learning. The four negative factors were structural inhibitors, lack of time (heavy workloads), an overwhelmingly fast pace of change, and negative attitudes.

A problem that we identify in the literature is that the concept of learning is immediately introduced in how the questions in empirical studies are put to respondents. To a large extent, the empirically based knowledge concerning managerial facilitation of learning outside the school context builds on studies that explicitly inquire about managers’ and employees’ own beliefs about learning. This means that these studies are not based on an elaborated, theory-grounded knowledge about learning processes; instead, conclusions are drawn on the basis of what interviewees themselves frame as learning. Also, most of these studies focus on the positive, facilitating side or friendly, enabling side of face-to-face communication. Our organisational research background implies a special interest in the indirect conditions created, that is, those beyond direct managerial interaction. In addition, our data required that the analysis captured the stricter and, at times, heavy-handed side of managerial interventions, not only the facilitating ones. As we, when collecting data, deliberately did not ask questions about learning; our data were not filtered by the interviewees’ beliefs about learning. Instead, we asked the middle managers about their work tasks, how they worked and what they tried to achieve during a period when decisive change was found necessary. The issue of learning was only introduced during our learning theoretical analysis work.

In terms of general leadership, we depart from Yukl's (Citation2002) definition of leadership as the ‘process of influencing others to understand and agree about what needs to be done and how it can be done effectively, and the process of facilitating individual and collective efforts to accomplish the shared objectives’ (p. 7). This definition introduces both process and collectivity, and points towards the leadership task of creating favourable learning conditions for the accomplishment of organisational goals. Furthermore, Yukl (Citation2009) points to the limitations of transformational and charismatic leadership in how organisational learning is influenced. Even though transformational leadership motivates individuals, the theory does not explain how leaders can influence collective learning in an organisation. Instead, Yukl argues, the emphasis on a single leader's direct influence on subordinates, which comes with the concept of transformational leadership, distracts attention from both the shared influence of multiple leaders and the influence of leaders on programmes and systems that are relevant to collective learning. In addition, we use influence as a term to describe the intentional acts that managers described to us, whereas our theory-based concepts used for the analysis of such acts are direct and indirect pedagogic interventions (see theory section). To our knowledge, the literature about managerial work is limited in explicating managers’ acts of influence as condition-creating interventions in work-integrated learning processes.

When we enter the school leadership literature as researchers from outside the school context, two things become obvious. First, it appears knotty and difficult to penetrate due to a variety of terms, such as educational, educative, instructional, learning-centred or pedagogical, that are defined and used in different ways by different authors – something Harris (Citation2004, Citation2007) also claims. It is not clear whether the terms have such names only to reflect that the leadership takes place in a school environment, or they are thought to point to some specific learning or teaching processes. The emergence of these terms may partly be due to the research field having the highly normative ambition of helping to create effective schools, especially in a time when the quality of schools is on the political and societal agendas, not least today in Sweden. Different research streams have been developed in relation to each other and introduce a number of different thought models recommended for principals to support students’ results (e.g. Hallinger, Citation2003, Citation2005; Macneill, Cavanagh, & Silcox, Citation2005; Male & Palaiologou, Citation2012; Webb, Citation2005). Consequently, these leadership labels are not seldom used to define right from wrong; they emerge as weapons in the struggle for how to best advance principals’ leadership. In Sweden, we see that notions of right and wrong thinking are intensified as the national school authorities compile and rewrite international school research from, for example, John Hattie or Helen Timperley (e.g. The National Agency for Education, Citation2013), with the intention of disseminating it widely. Second, there is an extensive borrowing, transfer and reuse of general organisational and leadership concepts developed in other contexts (see, e.g., Hoy & Miskel, Citation2008). In the process of doing so, concepts become more difficult to grasp as they get loaded with partly new content, when they are blended with school-specific concepts and contexts; for example, this is the case when Hallinger (Citation2003), inspired by Leithwood, develops instructional leadership via an integration with transformational leadership (Bass, Citation1985; Burns, Citation1978).

As we, in our analysis of managerial acts of influence, use the concepts of direct and indirect pedagogic interventions, we looked for a similar concept usage in the empirically based literature on school leadership. We were unable to find any previous research that has investigated principals’ pedagogical tasks from a learning theoretical perspective. It seems reasonable to theorise that a learning theoretical perspective may strengthen the understanding of the character of the learning processes involved in direct and indirect managerial influence in the workplace. We present those theoretical points of departure in the following section.

Learning theoretical point of departure

The main point of departure for the learning theoretical analysis of empirical data concerns work-integrated learning. Work-integrated learning is closely interconnected with the development of work-related skills and competence (Ellström, Citation2001) and is a key factor in any organisation's performance. Such learning has the potential to enable people to better carry out individual and joint tasks in relation to intentions and organisational goals. This theoretical lens makes possible the identification of everyday learning processes that are intervened into and allows us to focus on an aspect of managers’ daily work such as a learning-oriented task. Following Ellström (Citation2011) and ‘contrary to much current research in this field’, we conceptualise learning in work ‘neither as a social process inseparable from work practices nor as a purely cognitive process’ (p. 105). Next, we introduce our central concepts.

Learning, competence and action

Learning is the process through which people change their ways of thinking and/or acting, and when work integrated, it is the process that generates competence. It is viewed as an experience-based process (Dixon, Citation1994; Döös, Citation1997; Kolb, Citation1984). Experiential learning theory (ELT) has been used and developed in studies of collective learning in teams and networks in various work settings (e.g. Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2011; Fejes & Andersson, Citation2009; Ohlsson, Citation2013) and also to understand organisational learning (Dixon, Citation1994; Döös, Johansson, & Wilhelmson, Citation2015b). Kolb (Citation1984) defines experiential learning as ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (p. 38). His emphasis is rather on the process than on the content or outcome (Kolb, Citation1984; Kolb & Kolb, Citation2005, Citation2010). This paper draws on ELT's constructivist roots, thereby stressing the active contributions of a learning subject (usually an individual or a group) to what is learned and emphasising that learning occurs as a process of interaction between people and situations (Schunk, Citation2004). In accordance with ELT, we regard learning as an action-based process that changes the learner's way of thinking and/or acting. We find ELT useful in problematizing and conceptualising informal learning processes. Competence is understood as an ability to act skilfully in a specific context and situation. Apart from being individual, competence is also carried in the relationships between people – a phenomenon that has been conceptualised as competence bearing relations (Döös, Citation2007). Such collective competence is built through the work-integrated interaction that constitutes the social infrastructure of importance to the growth and quality of competence.

Experiential learning is grounded in people's actions and their reflection on those actions. Actions are carried out in situations that have limitations and possibilities, where an individual's actions emerge depending on how he or she understands the situation at hand (Döös, Citation1997; Suchman, Citation1987). In all their actions, people continuously construct and reconstruct their own understanding, as well as their own and each others’ conditions for learning. Action in this paper refers to something an individual intentionally does. The outcome of actions may be intended (results) or not intended but following from the action (consequences) (Reason, Citation1990). This learning perspective leads to an understanding of learning as a work-integrated by-product of people carrying out tasks (Döös, Citation2007), and means three things: (1) people do not have to be aware of the fact that they are learning; (2) learning is not bounded to training activities but is ongoing in daily working life, which means that managerial acts of influence can be analysed as opportunities for learning and as constituting a certain learning environment (Johansson, Citation2011); and (3) learning occurs through an interplay between the affordances of the workplace and individuals’ readiness to learn (Löfberg, Citation1989), and where different types of learning are stimulated under different contextual circumstances (Johansson, Citation2011).

Managers’ pedagogic interventions and learning-oriented leadership

The concept of learning-oriented leadership is used to analyse and understand managers’ aspiration to influence work and is defined as interventions in learning processes that are integrated in the carrying out of work tasks (Döös et al., Citation2015a; Wilhelmson, Johansson, & Döös, Citation2013). Based on experiential learning theory (Kolb, Citation1984; Kolb & Kolb, Citation2010), Döös and Ohlsson (Citation1999) make a distinction between two types of pedagogic interventions: direct and indirect. This distinction is essential to understand how the data were analysed. Direct pedagogic interventions use communication as the means to influence people's conceptions, for example, to inform someone about the risks of smoking in order to make him or her aware of the need to quit. Such an intervention is easy to make, but the effect on action is often limited. Indirect pedagogic interventions influence actions and conceptions via changed environmental preconditions; changed preconditions make people behave differently, which inevitably produces new related thinking. Indirect interventions concern changes in the organisational context (the work environment) and, for a long time, have been key in preventing occupational accidents and risky behaviour (Reason, Citation1990; Sundström-Frisk, Citation1996). An example of changed preconditions in the school setting would be if a system is introduced with two teachers in each class. Having two teachers, who share responsibility and see each other in action, changes radically the preconditions of the task (Larsson, Citation2004).

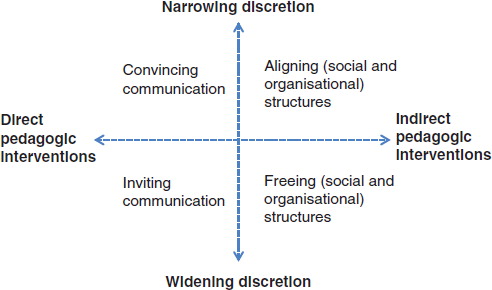

Thus, interventions can be understood as taking place in two different worlds: in the specific work environment or in the individuals’ meaning context, that is, their conceptions of this specific environment (Döös & Ohlsson, Citation1999). While face-to-face communication intervenes directly in individuals’ meaning context, changes in the local work environment form new action and also the accompanying concrete experiences that bring about adjusted thinking (Döös & Ohlsson, Citation1999). The distinction between direct and indirect pedagogic interventions is based on the means used in an intervention, that is, verbal communication or changes in the organisational context. Another dimension of pedagogic interventions concerns whether the interventions narrow or widen discretion. Ellström (Citation1992) distinguishes between discretion (as degrees of freedom) in which specific targets and expected ways of working are given and discretion in which space is afforded for individual actors to be part of the framing of tasks and ways of working.

Method

The research behind this paper was part of a larger study and was performed using qualitative methods in a case study (Döös et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b). In relation to the categories of learning-oriented leadership presented below, the study relied on abductive reasoning (Fann, Citation1970) and analytical generalisation within a chosen theoretical perspective (Firestone, Citation1993; Yin, Citation1989), and had the ambition of contributing concepts and developing the theory being used (Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2014). Analytic generalisation is favourable in qualitative research and case studies (Firestone, Citation1993; Yin, Citation1989). In relation to the school context, the idea of case-to-case transfer (Firestone, Citation1993) is applicable. Case-to-case transfer means that the researcher provides enough case material for readers ‘to assess the match between the situation studied and their own’ (p. 18). In summary, this means that we, on the basis of our learning theoretical point of departure, are abstracting phenomena from the studied software communication context and offering that understanding to the reader, who then transfers and applies it to the context of schools.

The empirical setting was a global organisation within the software communication industry. The study included middle managers on three organisational levels, who influenced each other's work and assumptions horizontally as well as vertically. The data were collected in 24 semi-structured interviews with 21 middle managers; there were also observations of management team meetings and field visits were made. As explained above, the interviews purposely did not contain questions about influencing learning, rather they focussed on ways of working during a period of organisational change. The aspect of learning was brought in by the theoretical perspective employed in the data analysis (see, e.g., Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2014). The units in which the middle managers were working are referred to as Ypsilon (5,000 employees) and Zeta (1,200 employees). The Zeta unit was part of the Ypsilon unit. The data used for this paper were collected from interviews with nine managers, who were all from the management team of Zeta (the overall manager, his deputy manager, six middle managers and one programme manager). During the data collection, an opportunity to get access to relevant data presented itself as the managers of Zeta worked to change mindsets and ways of working in their organisation, which is why Zeta and its management team were chosen for the analysis of learning-oriented leadership. These changes were also related to discussions and mutual influence processes in Ypsilon's management team, of which Zeta's top manager was a part.

The analytical emphasis was on how influence on learning processes was manifest in the managers’ descriptions of how they worked. An analysis protocol was constructed in which either direct or indirect acts of influence were specified. Direct pedagogic interventions (Döös & Ohlsson, Citation1999) were searched for as verbal communication attempts to influence sensemaking in order to change conceptions held by managers as well as staff. Indirect pedagogic interventions were searched for as managerial acts of influence that strived towards changing the organisational context, thus producing changed conditions for work-integrated learning. Early in the analysis, a distinction emerged between examples of managerial acts that either narrowed or widened discretion (Ellström, Citation1992). Two types of pedagogic intervention (direct/indirect) along with the two kinds of approaches to discretion (narrowing/widening) were then chosen to structure the findings into the categories of learning-oriented leadership that are presented in the findings section.

Contextualising the case

Here follows a brief contextualisation that explains the last decade of the corporation's history. Around the turn of the millennium, at the burst of the IT-bubble, the corporation's customers could not afford to buy its products and the number of staff was reduced by over a third in the years that followed. By the autumn of 2008, the corporation had partly recovered; it was in profit again, small innovation cells were started and some managers were freeing up money for risk-taking:

In the difficult years, many managers became too obedient, so I think it is good that he dares a bit, we may get back a little civil disobedience. (Middle manager L)

Part of the problem is that, during the downturn, a lot of people […] learned the behaviour of predictability and quality, and we have to kind of unlearn that a little bit, not completely because we need to keep that base, the [corporation] brand. (Middle manager M)

Two years later, on our return for the main data collection, there were islands of early adopters of a variety of ‘new agile ways of working’,Footnote1 alongside the usual focus on delivery with quality in operational technology development. The external business landscape was perceived as highly competitive, with Chinese and Indian companies transforming themselves from so-called fast followers into technology leaders. To remain competitive, the middle managers of Ypsilon were cooperating to anchor these new agile ways of working, both within and across subunits (the description of managerial influence presented below is based in this period). In Ypsilon, this was regarded as a bold, full-scale experiment with an uncertain outcome.

Categories of learning-oriented leadership

The middle managerial work at Zeta included a number of tasks during which the managers intended to influence different parties in the organisation (staff, colleagues and also superior managers) regarding the ways work was carried out. By focussing on the managers’ statements about what they did when attempting to influence, thematic empirically based categories of learning-oriented leadership were generated. The presentation of the findings is grouped into direct and indirect pedagogic interventions. A brief generalised interpretation of each category is presented.

Direct pedagogic interventions – via communication attempts

Communication is an integral part of all managers’ leadership. Managers in this study took part in numerous formal meetings and were also engaged in informal conversations, for example, in the hallways. When searching for different qualities of managers’ direct influence activities, we discerned, on the one hand, attempts to convince others with information and arguments and, on the other hand, attempts to invite others to a mutual exchange of views.

Convincing communication

Among the managers, convincing communication was discussed as a kind of educating task, that is, making others aware of the necessity of desired ways of thinking and doing. As managers were acting towards reaching their jointly set goals of the organisation, this approach entailed communication through lecturing, persuading and confronting. This approach was characterised by managers having a fixed view of the objectives and convincing others to do or think in the same way. Here, managers were acting in a control-oriented fashion, in the sense that they were trying to control how something should be interpreted or done.

One example of this type of intervention was a middle manager who attempted to convince a subordinate manager at a local site to show the necessary leadership to prevent the site from being closed down. In another situation, the senior manager of Ypsilon was rebuked by a subordinate manager for not making enough effort to motivate and inspire staff.

Inviting communication

In contrast to convincing communication, the category of inviting communication is characterised by mutuality, an openness to differences of opinion and an interest in listening and learning from others. When being open in this way, managers described themselves as active listeners, reasoning and searching for common understanding. Talking and listening jointly was considered important in catching, valuing and disseminating ideas. The managers acted in an emergence-oriented fashion, trusting the value of an open process in which diversity in opinions and listening to one another would bring forward new solutions. The managers also said they actively invited other people to be part of the decision-making processes, that is, enacting high levels of involvement and a wide distribution of autonomy.

Inviting communication was exemplified by managers engaging in collective conversations, where mutual understanding was developed through ideas being shared and arguments being tested. In one example, a manager said that he did not want to manage simply by telling people what to do. Instead, everyone would experiment with different ways of doing things and then discuss together what had worked well. The managerial task was also described as sitting in a lot of meetings, discussing various problems and solving them, which included listening and sometimes choosing between alternatives and suggesting a way forward.

Indirect pedagogic interventions – via change in the organisational context

In managers’ descriptions of their work, we identified activities in which they attempted to influence conceptions indirectly by altering organisational preconditions for work-integrated learning and thereby changing how work was carried out. When searching for different qualities of managers’ indirect interventions, we discerned attempts both to align and free structures. The alignment could either concern social structures (e.g. institutionalised norms, rules) through imposing requirements to influence ways of working or organisational structures that, for example, meant a redesign of the organisation chart or of the principles behind team composition. The freeing of structures could either concern social structures, such as a creation of action space that afforded autonomy to people, or organisational structures that were broken up or disregarded.

Aligning social and organisational structures

There are times when the middle management of an organisation needs to redesign and (re)connect different parts of the organisation to achieve more alignment in how work is carried out. As already mentioned, we entered the case-study organisation during such a period.

Setting requirements to influence ways of working

The alignment of social structures occurred when the middle managers imposed requirements as a means to influence the ways in which work was carried out. They also put the decisions into practice. The method of setting of these requirements stretched beyond direct interaction and communication, but may, of course, have required direct communication to be carried out. Thus, the primary mechanism here was not to convince by communicating, but through reliance on the decisions made, the goals set and the procedures to control those.

The middle managers set demands and followed up goals at both individual and organisational levels. For example, they set individual goals for people to use their competence and methods across intra-organisational boundaries. Another example was that the top manager of Zeta, the deputy manager, the HR-specialist and some other people systematically visited and, with the help of well-developed routines, scrutinised the performance of all subunits.

Redesigning organisational structures to support agile ways of working

As part of their work, the managers occasionally redesigned the organisational structures of their units to better accomplish the goals that were set, that is, they aimed to find what they thought were the most appropriate organisational structures for certain ways of working. On this occasion, managers believed that the redesign of organisational structures would force people to think in new ways, create new energy and new ways of acting, and prevent stagnation and reliance on old thought patterns. They regarded an extensive and formal organisational restructuring as necessary to fundamentally influence mindsets and ways of working. This was done, for example, by reorganising how teams were composed and where they belonged, which also supported the decision to move towards agile ways of working. Also, managers started to collaborate to find an entirely new organisational structure that they described as bold and supportive to modern (agile) work, as it was designed to force subunits into cooperation. Thus, this structural redesign was seen as a force for learning, even though the managers themselves did not conceptualise it as such.

Freeing social and organisational structures

As mentioned above, the alignment of social and organisational structures contrasted with the freeing of those structures. The two freeing ways of influencing are described below.

Allowing and creating space for action

In freeing social structures, contrary to imposing requirements to influence the work carried out, managers made space for others and involved them in strategic work. Overall, this kind of influence can be seen when managers advocated high levels of involvement and wide distribution of autonomy. Managers said they acted with the intention of designing social structures that gave space for the emergence of new ways of working, based on what others in the organisation found appropriate.

For example, the members of one management team were given greater responsibility and became integral to their manager's running of the business – this was done due to a belief in the power of widespread involvement and autonomy. Another example concerned the creation of new meeting spots to stimulate new patterns of interaction and the wider sharing of experiences. Another case illustrates how a manager allowed individual autonomy to a project leader, despite the fact that it occasionally collided with both rules and other people – and gave the manager extra work. This signalled that, in this organisation, formal rules were subordinate to goals; informal rules, such as those created through such examples, say that critical customer situations are best solved by heroes that succeed despite impossible demands.

Breaking up or intentionally disregarding organisational structures

The managers dared to abandon the orthodoxy of rules and systems, which not only allowed for space within structures, but even the breaking up or disregarding of structures. In fact, there was a complete break with the existing principle of organisation of the entire Zeta unit. In addition, large projects that were previously run by senior people were handed to small, empowered teams to increase effectiveness. In a pressurised period, when the organisation had to push itself to complete work within seemingly impossible timeframes to retain its customer, key players, for example, set aside formal decision-making lines, and three people took the lead in securing developmental deliveries. On other occasions, temporary task force units were created to solve critical situations to tight deadlines when the ordinary ways of organising work were not sufficient. In such ways, established organisational structures were deliberately set aside for various reasons.

Discussion

This paper has presented the analytical concept of learning-oriented leadership based on an analysis of managerial acts of influence in a case study within the software communication industry and with the aim of discussing this as a potential contribution to the school context. Eraut's (Citation2011) empirical studies consistently show that most informal learning occurs ‘as a by-product of normal working processes’ (p. 186; orig. italics). This points to the importance of studying how conditions for learning processes may also be created even though there is no explicit aim of facilitating learning. In our case study, the company's explicit aim was to survive in a highly competitive market. Following Eraut's (Citation2011) classification of learning processes according to whether their principal intention is working or learning, our focus lies where the primary intention is working. As shown above, the analysis of managerial acts of influence yielded four main categories according to a division between direct and indirect pedagogic interventions into work-integrated learning processes, and the acts of influence that narrowed or widened others’ discretion (see ).

Fig. 1. Categorisation of managerial acts of influence and four identified main categories of learning-oriented leadership.

The two main forms of indirect pedagogic intervention were each divided into two subcategories, as both the aligning and freeing of structures concerned both social and organisational structures. On the one hand, managers were engaged in the narrowing of discretion through acts of influence that were built on fixed views of objectives, trust in predetermined organisational goals and procedures, on and control of the interpretations of objectives. Managers’ acts of influence were goal- and control-oriented. On the other hand, managers were engaged in widening the discretion built on confidence in the emerging competence, on favouring diversity of opinion and listening and supporting a high level of involvement of others. Managers facilitated the empowerment and authorisation of people, afforded discretion and trusted the outcome. They acted in an emergence-oriented fashion, with an interest in letting the objectives and means of work emerge through continuous interaction. This also favoured the wider distribution of power in the organisation. In these ways, the managers balanced between convincing and inviting communication on the one side and between aligning and freeing of structures on the other. In contrast to Ellinger and Cseh's (Citation2007) study – in which the facilitation of learning was studied as a separate task that people found difficult or uninteresting – an overwhelming pace of change and a lack of time due to work overload were, in our case study, reasons for the organisation to learn as managers were dealing with a change endeavour that was perceived as necessary for the future of the company.

Each manager had a repertoire of influencing acts at his or her disposal and moved between the different categories of acts of influence. One kind of influence changed into another over time, as managers intervened and influenced the work carried out, thereby creating affordances for work-integrated learning. The use of learning theory as a basis for analysing managers’ acts of influence was decisive in expanding the understanding of learning-oriented leadership beyond managerial communication with single individuals. This perspective creates an understanding that goes beyond previous research, where the beliefs of interviewees about how to intentionally facilitate learning are the primary focus (e.g. Beattie, Citation2006; Doornbos et al., Citation2004; Ellinger, Citation2005). In relying on analytical generalisation (Firestone, Citation1993; Yin, Citation1989) within a chosen theoretical perspective, the concept of learning-oriented leadership contributes to the theory on experiential (Dixon, Citation1994; Döös et al., Citation2015b; Döös & Wilhelmson, Citation2011; Kolb, Citation1984; Ohlsson, Citation2013), work-integrated learning (Ellström, Citation2001; Ellström, Ekholm, & Ellström, Citation2008).

Back to the school context

So what does this mean for the school setting, for the rhetoric about pedagogical leadership in Sweden (Nestor, Citation2006), and in relation to Harris’ (Citation2004, Citation2007) ‘terrain of labels’? What is stressed here is the potential of linking leadership to learning theory and thus, in the school context, liberating ourselves from contaminating pedagogical leadership with the fact that the main task of the activity is pedagogic. Here, the study of an empirical context other than schools contributes to an analytical separation of the pedagogical leadership task from the pedagogical core task, which may be useful when returning to the school context. On a learning theoretical basis, and with empirical material from a non-educational setting, it was possible to identify learning-orientated aspects of managers’ influencing attempts. In practice, managers exercise influence in a number of ways, and we think it is important to understand this influence as intentional or unintentional intervention in learning processes. There is potential advantage in acknowledging multiple ways of working instead of rigidly defining right from wrong. Furthermore, high-quality management in schools is strongly associated with better educational outcomes (Bloom, Lemos, Sadun, & Van Reenen, Citation2015), and principals have an impact on both working conditions and student outcomes (Böhlmark, Grönqvist, & Vlachos, Citation2012). The overall conclusion of a new official government report (SOU, Citation2015:22) is that there is a great need to reinforce principals ‘pedagogical leadership capacity […] One important element of the pedagogical leadership role […] is building and managing a well-functioning school organisation’ (pp. 17–18). The pedagogical leadership of principals is claimed to be ‘vital to the quality and development of school operations’ (p. 17), while many principals have insufficient time for the task. This paper's contribution lies in examining what it may mean for managers to lead and govern learning processes without thinking explicitly about learning, which may potentially also be of value in improving the quality of school leadership and addressing the problems detailed above.

Before continuing this discussion, we would like to make a few comments about our own observations of some similarities and differences between the studied context and the school context. Being organisation researchers with experience from a number of industries and sectors, it is striking the extent to which the principal's leadership within the school context is talked about and described as the most complex and difficult leadership there is; we would rather talk about variations in what characterises complexity and difficulty in the two contexts. The type of complexity witnessed in our software communication case study concerns a much faster pace of change and an element of international competition that does not exist in Swedish schools. This difference is related to a number of crucial technological expert competencies that have to be constantly kept up to date, adapted and even transformed in order to function well together inside devices and software solutions. Being at the forefront of competition requires that competence is not only continually developed but created, in terms of both leadership and technology. An interesting similarity between the two contexts is the awareness of industry-specific trends. In the software communication industry, at the time of our empirical work, this especially concerned agile ways of working, whereas the principals who we meet now seem collectively impregnated with collegial learning and systematic quality work. Thus, in both cases, people clearly align with branch-specific trends. In the school context in Sweden, this trend is supported by a chorus of partly disagreeing experts and school researchers, as well as by the two national school authorities. In the software communication industry, there is no such national control, and, in that sense, there is more freedom to invent new technology and ways of organising and working.

In the educational leadership literature concerning instructional, pedagogic, direct and indirect leadership in schools, the interpretation of each concept is shifting and thus unstable. Here, we offer an alternative suggestion for how to understand what principals do in order to influence the work in their organisations. This may also, in practice, imply interventions by principals in teachers’ work-integrated experiential learning processes. Learning-oriented leadership, as an analytical concept, may illuminate how everyday leadership (Holmberg & Tyrstrup, Citation2010) is strategic in its interventions. The concept of learning-oriented leadership and its categories may also be used as tools to analyse both principals’ own practice and, for research, empirical data about the work of principals. Our empirical analysis shows that – when expanding learning-oriented leadership as a unit of analysis to also include activities that are part of managers’ organising of everyday work practice – it becomes clear that a number of managerial activities bring about opportunities for work-integrated learning. This goes beyond the learning-committed manager of the HR studies (e.g. Doornbos et al., Citation2004; Ellinger, Citation2005) and beyond directly asking for interviewees’ own beliefs about learning (e.g. Ellinger & Bostrom, Citation2002).

To conclude, the learning-oriented model for the categorisation of managerial acts of influence presents different options for managers, including principals, to intervene into their employees’ learning and competence, both individually and collectively. Thereby, principals can, in their profession, rely on a combination of different influencing skills. Future joint research between educational and organisational researchers seems promising in order to analyse the work of principals in these respects. Finally, each reader of this paper from the school context may now continue adding to the list of differences and similarities to help decide the potential value of this contribution in the school setting.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marianne Döös

Marianne Döös is a Professor in Education, and a researcher within Organisational Pedagogics at Stockholm University since 2008. Her research deals with the processes of experiential learning in contemporary work settings, on individual, collective and organisational levels. Topical issues concern interaction as carrier of competence in relations, shared and joint leadership, conditions for competence, organisational learning and change. Marianne Döös has authored and co-authored many articles and books. Two relevant examples among her publications are ‘Collective learning: Interaction and a shared action arena’ (in the Journal of Workplace Learning, 2011) and ‘Organizational learning as an analogy to individual learning?’ (in Vocations and Learning, 2015). [email protected]

Lena Wilhelmson

Lena Wilhelmson is an associate professor and a senior researcher at Stockholm University in Sweden, within the field of organisational learning. Her research deals with individual and collective learning in renewal processes in working life. Her areas of interest include adult education, dialogue and learning processes. Also studies concerning shared and joint leadership have been conducted by Wilhelmson. Lena Wilhelmson has authored and co-authored many articles and books. Two relevant examples among her publications are ‘Enabling transformative learning in the workplace’ (in the Journal of Transformative Education, 2015) and ‘Manager’s task to support integrated autonomy at the workplace’ (in the International Journal of Business and Management, 2013). [email protected]

Notes

1 A group of software development methodologies, in which requirements and solutions evolve through iterations and incremental development between people with different functional expertise.

References

- Agashae Z., Bratton J. Leader-follower dynamics: Developing a learning environment. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2001; 13(3): 89–102.

- Amy A.H. Leaders as facilitators of individual and organizational learning. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2008; 29(3): 212–234.

- Bass B.M. Leadership and performance beyond expectations. 1985; New York: Free Press.

- Beattie R.S. Line managers and workplace learning. Learning from the voluntary sector. Human Resource Development International. 2006; 9(1):99–119. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13678860600563366.

- Billett S. Workplace participatory practices: Conceptualising workplaces as learning environments. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2004; 16(6): 312–324.

- Bloom N., Lemos R., Sadun R., Van Reenen J. Does management matter in schools?. The Economic Journal. 2015; 125(May): 647–674.

- Bredin K., Söderlund J. Reconceptualising line management in project-based organisations. The case of competence coaches at Tetra Pak. Personnel Review. 2007; 36(5): 815–833.

- Burns J.M. Leadership. 1978; New York: Harper & Row.

- Böhlmark A., Grönqvist E., Vlachos J. The headmaster ritual: The importance of management for school outcomes (Working paper 2012:16). 2012; Uppsala: The Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy (IFAU).

- Cedefop. Learning while working. Success stories on workplace learning in Europe. 2011; Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union.

- Dixon N. The organizational learning cycle. How we can learn collectively. 1994; London: McGraw-Hill.

- Doornbos A.J., Bolhuis S., Simons P.R.-J. Modeling work-related learning on the basis of intentionality and developmental relatedness: A noneducational perspective. Human Resource Development Review. 2004; 3(3): 250–273.

- Döös M. The qualifying experience. Learning from disturbances in relation to automated production. 1997; Solna: National Institute for Working Life. In Swedish Work and Health 1997:10.

- Döös M, Farrell L., Fenwick T. Organizational learning. Competence-bearing relations and breakdowns of workplace relatonics. World year book of education 2007. Educating the global workforce. Knowledge, knowledge work and knowledge workers. 2007; London: Routledge. 141–153.

- Döös M., Johansson P., Wilhelmson L. Beyond being present: Learning-oriented leadership in the daily work of middle managers. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2015a; 27(6):408–425. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JWL-10-2014-0077.

- Döös M., Johansson P., Wilhelmson L. Organizational learning as an analogy to individual learning? A case of augmented interaction intensity. Vocations and Learning. 2015b; 8(1):55–73. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12186-014-9125-9.

- Döös M., Ohlsson J, Ohlsson J., Döös M. Relating theory construction to practice development – Some contextual didactic reflections. Pedagogic interventions as conditions for learning. 1999; Stockholm: Department of Education, Stockholm University. 5–13.

- Döös M., Wilhelmson L. Collective learning: Interaction and a shared action arena. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2011; 23(8): 487–500.

- Döös M., Wilhelmson L. Proximity and distance: Phases of intersubjective qualitative data analysis in a research team. Quality & Quantity. 2014; 48(2):1089–1106. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11135-012-9816-y.

- Ellinger A.D. Contextual factors influencing informal learning in a workplace setting: The case of “reinventing itself company.”.Human Resource Development Quartely. 2005; 16(3): 389–415.

- Ellinger A.D., Bostrom R.P. An examination of managers’ beliefs about their roles as facilitators of learning. Management Learning. 2002; 33(2): 147–179.

- Ellinger A.D., Cseh M. Contextual factors influencing the facilitation of others’ learning through everyday work experiences. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2007; 19(7): 435–452.

- Ellström E., Ekholm B., Ellström P.-E. Two types of learning environment. Enabling and constraining a study of care work. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2008; 20(2): 84–97.

- Ellström P.-E. Competence, education and learning in working life. Problems, concepts and theoretical perspectives. 1992; Stockholm: Publica. In Swedish.

- Ellström P.-E. Integrating learning at work: Problems and prospects. Human Resource Development Quarterly. 2001; 12(4): 421–435.

- Ellström P.-E. Practice-based innovation: A learning perspective. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2010; 22(1/2): 27–40.

- Ellström P.-E, Malloch M., Cairns L., Evans K., O'Connor B.N. Informal learning at work: Conditions, processes and logics. The Sage handbook of workplace learning. 2011; London: Sage. 105–119.

- Eraut M, Malloch M., Cairns L., Evans K., O'Connor B.N. How researching learning at work can lead to tools for enhancing learning. The Sage handbook of workplace learning. 2011; London: Sage. 181–197.

- Fann K.T. Peirce's theory of abduction. 1970; Haag: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Fejes A., Andersson P. Recognising prior learning: Understanding the relations among experience, learning and recognition from a constructivist perspective. Vocations and Learning. 2009; 2(1): 37–55.

- Firestone W.A. Alternative arguments for generalizing from data as applied to qualitative research. Educational Researcher. 1993; 22(4): 16–23.

- Hallinger P. Leading educational change: Reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Cambridge Journal of Education. 2003; 33(3): 329–351.

- Hallinger P. Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools. 2005; 4(3): 221–239.

- Harris A. Distributed leadership and school improvement. Leading or misleading?. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. 2004; 32(1): 11–24.

- Harris A. Distributed leadership: Conceptual confusion and empirical reticence. International Journal of Leadership in Education. 2007; 10(3): 315–325.

- Holmberg I., Tyrstrup M. Well then – What now? An everyday approach to managerial leadership. Leadership. 2010; 6(4): 353–372.

- Hoy W.K., Miskel C.G. Educational administration. Theory, research, and practice. 2008; 8th ed., Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

- Illeris K. A model for learning in working life. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2004; 16(8): 431–441.

- Johansson P. Learning environments in the workplace. The construction of learning environments in a VET-program from an organizational pedagogical point of view. 2011; Stockholm: Department of Education, Stockholm University. In Swedish.

- Kolb A.Y., Kolb D.A. Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2005; 4(2): 193–212.

- Kolb A.Y., Kolb D.A. Learning to play, playing to learn. A case study of a ludic learning space. Journal of Organizational Change Management. 2010; 23(1): 26–50.

- Kolb D.A. Experiential learning. Experience as the source of learning and development. 1984; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Koopmans H., Doornbos A.J., van Eekelen I.M. Learning in interactive work situations: It takes two to tango; why not invite both partners to dance?. Human Resource Development Quartely. 2006; 17(2): 135158.

- Larsson P. Conditions of change. A study of organisational learning and change in schools. 2004; Stockholm: EFI, Stockholm School of Economics. (In Swedish).

- Larsson P., Löwstedt J, Löwstedt J., Larsson P., Karsten S., Van Dick R. Refining the expedition: Individual, team and organisational development. From intensified work to professional development. 2007; Bruxelles: P.I.E. Peter Lang.

- Löfberg A, Leymann H., Kornbluh H. Learning and educational intervention from a constructivist point of view: The case of workplace learning. Socialization and learning at work. A new approach to the learning process in the workplace and society. 1989; Aldershot: Avebury. 137–158.

- Macneill N., Cavanagh R.F., Silcox S. Pedagogic leadership: Refocusing on learning and teaching. International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning. 2005; 9(2):

- Male T., Palaiologou I. Learning-centred leadership or pedagogical leadership? An alternative approach to leadership in education contexts. International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice. 2012; 15(1):107–118. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2011.617839.

- Nestor B. Pedagogic leadership in a principal and organisational perspective. 2006; Stockholm: School of Education, Centre for Educational Management. 146–189. In Swedish.

- Neumerski C. Rethinking instructional leadership, a review: What do we know about principal, teacher, and coach instructional leadership, and where should we go from here?. Educational Administration Quarterly. 2012; 49(2): 310–347.

- Noer D. Behaviorally based coaching: A cross-cultural case study. International Journal of Coaching in Organizations. 2005; 3(1): 14–23.

- Ohlsson J. Team learning: Collective reflection processes in teacher teams. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2013; 25(5): 296–309.

- Reason J. Human error. 1990; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sandberg J., Targama A. Managing understanding in organizations. 2007; London: Sage.

- Schunk D.H. Learning theories. An educational perspective. 2004; 4th ed., Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- SOU. The head teacher and the chain of command. 2015; Stockholm: Swedish Government Official Reports. In Swedish, English summary 22.

- Suchman L.A. Plans and situated actions. The problem of human machine communication. 1987; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sundström-Frisk C, Menckel E., Kullinger B., Axelsson P.-O., Hallgren L.-E. The human factor. Fifteen years of occupational-accident research in Sweden. 1996; Stockholm: Swedish Council for Work Life Research. 75–90.

- The National Agency for Education. Research for the class room. Scientific ground and tested experience in practice. 2013; Stockholm: The National Agency for Education. In Swedish.

- Wallo A. The leader as facilitator of learning at work. A study of learning-oriented leadership in two industrial firms. 2008; Linköping: Linköping University.

- Warhurst R.P. Learning in an age of cuts: Managers as enablers of workplace learning. Journal of Workplace Learning. 2013; 25(1): 37–57.

- Webb R. Leading teaching and learning in the primary school. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. 2005; 33(1): 69–91.

- Wilhelmson L., Johansson P., Döös M, Wang S., Hartsell T. Bridging boundaries: Middle managers’ pedagogic interventions as technology leaders. Technology integration and foundations for effective leadership. 2013; Hershey, PA: IGI Global. 278–292.

- Yin R.K. Case study research. Design and methods. 1989; Newbury Park: Sage.

- Yukl G. Leadership in organizations. 2002; 5th ed., Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall International.

- Yukl G. Leading organizational learning: Reflections on theory and research. The Leadership Quarterly. 2009; 20: 49–53. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.11.006.