Abstract

Background: In an interprofessional training ward (ITW), students from different health professions collaboratively perform patient care with the goal of improving patient care. In the past two decades, ITWs have been established world-wide and studies have investigated their benefits. We aimed to compare ITWs with respect to their logistics, interprofessional learning outcomes and patient outcomes.

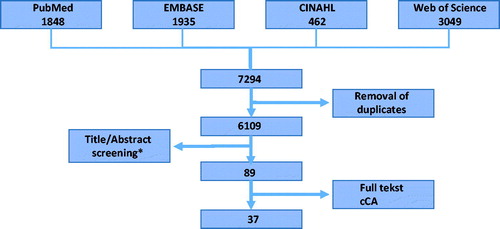

Methods: We explored PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science and EMBASE (1990–June 2017) and included articles focusing on interprofessional, in-patient training wards with student teams of medical and other health professions students. Two independent reviewers screened studies for eligibility and extracted data.

Results: Thirty-seven articles from twelve different institutions with ITWs were included. ITWs world-wide are organized similarly with groups of 2–12 students (i.e. medical, nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and pharmacy) being involved in patient care, usually for a period of two weeks. However, the type of clinical ward and the way supervisors are trained differ.

Conclusions: ITWs show promising results in short-term student learning outcomes and patient satisfaction rates. Future ITW studies should measure students’ long-term interprofessional competencies using standardized tools. Furthermore, a research focus on the impact of ITWs on patient satisfaction and relevant patient care outcomes is important.

Introduction

“Once students understand how to work interprofessionally, they are ready to enter the workplace as a member of the collaborative practice team. This is a key step in moving health systems from fragmentation to a position of strength.” (Gilbert and Hoffman Citation2010)

Today’s management of health care problems is highly dependent on interprofessional (IP) teamwork. An increasing number of reports stress the importance of integrating interprofessional education (IPE) into health professions education curricula reflecting the need to prepare students to practice in this complex and challenging environment (Barr Citation2002; D'Amour and Oandasan Citation2005; Gilbert and Hoffman Citation2010). Besides the increasing complexity of the healthcare system as incentive for IPE, collaboration in itself remains a challenging process in which team processes can sometimes compete with maintaining one’s own professional identity (Kvarnstrom Citation2008). IP collaboration has now been firmly anchored as an important goal within most health professions educational frameworks, such as the CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework (Frank and Sherbino Citation2015). Interprofessional education (IPE) occurs “when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care” (Barr Citation2002; Mann et al. Citation2009). A major question still is how to implement IPE most effectively within health professions curricula.

Known IPE teaching strategies include IP lectures, study groups, patient simulation assignments and IP clinical placements. Training in a clinical workplace offers students a level of authenticity and responsibility that encourages learning (Koens et al. Citation2005). Examples of IPE training in a clinical workplace-based setting include both student-run outpatient clinics, which are typically outpatient health care clinics that provide disease-specific treatment to underserved and poor patients without insurance, and inpatient interprofessional training wards (ITWs) (Chen et al. Citation2014). The ITW is the focus of this study. We defined an ITW as an in-patient clinical ward where students from more than one health care profession (e.g. medical, nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and pharmacy students) are collaboratively responsible for patient care. Students often perform both profession-specific and interprofessional group tasks, such as washing a patient, in the ITW. Early reports about ITWs highlight advantages of workplace-based education by addressing professional stereotypes, understanding the work of other health care professionals and learning how to collaborate in an effective fashion (Wahlstrom et al. Citation1997; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004). Following the first ITW in Sweden in 1996, several other countries have started ITW initiatives as well (Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Meek et al. Citation2013; Morphet et al. Citation2014). In a recent review, Jakobsen et al. summarized findings on the organization and pedagogy on ITWs in Sweden and Denmark (Jakobsen Citation2016). This current review has no geographical limitation and describes inpatient ITWs world-wide. We limited the review to ITWs where medical students were included. The aim of the current literature review is to give an overview of experiences with ITWs focusing on the way in which the programs were organized, how student’s learning outcomes were assessed, how supervisors were trained and the effect on patient (satisfaction) outcomes. In addition, we assessed the quality of the studies. The aim of our literature review was to offer some guidance, based on a thorough assessment of the literature, to those who are considering starting an ITW including medical students.

Methods

Systematic literature search and study selection

A systematic literature search was performed using Pubmed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Web of Science databases on 10th June 2017. Synonyms for “interprofessional education”, “clinic/ward” or “outpatient department”, and “medical student/curriculum” (Supplemental Table S1) were used to find relevant articles. All titles and abstracts were screened for in- and exclusion criteria () by two independent reviewers (NO, HEW) to select relevant studies. For inclusion, the studies had to describe a program in which interprofessional groups of students (including at least one medical student as this was the focus of this study) were involved in real-life patient care in an in-patient setting. Articles describing out-patient placements, student-run free clinics and simulation programs and articles published before the year 1985 were excluded. Full text screening of all articles was conducted by two independent reviewers (NO, HEW) to assess if inclusion criteria were met. When they differed in opinion during the review process, a third independent reviewer (LCF) was consulted and consensus was reached by discussion. The literature search resulted in 6109 abstracts after removing duplicates (). After screening titles and abstracts, 90 articles were left for further selection; 52 articles were excluded after full-text screening. Thirty-eight articles concerning ITWs were included. Screening cross-references from included studies did not yield any additional articles. The third reviewer (LCF) was consulted four times.

Figure 1. Flowchart article inclusion. *Inclusion criteria: clinical in-patient interprofessional training program, full-time clerkship, real-life patient care, medical + at least one other type of health care student involved in program, Dutch/English article. Exclusion criteria: student-run free clinics, simulation ward/clinic, outpatient and ambulatory care projects, articles published <1985.

Data extraction process and outcome measures

Before starting the data extraction process, three of the authors (NO, HEW, and LCF) defined outcome measures and developed a data collection form to collect all the information necessary to answer our research questions. Charting categories included: author, year of publication, training ward location and type, number and type of students involved, the rotation duration, the learning objectives of the training ward, the type of student assessment (questionnaire, test, reflective sessions, and tool), the type of supervisors and whether they received training, the research question for each study, the type of research (quantitative/qualitative/mixed methods), the number of study participants, the research tool and the research outcome. Additionally, the methodological quality of all articles using a quantitative research design was assessed with the “Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument score” (MERSQI) including Kirkpatrick’s Four-Level Training Evaluation Model scores (Reed et al. Citation2007; Thistlethwaite et al. Citation2015). Scores for the item “validation tool” within the MERSQI score were only granted when methodological proof of validation was presented either in the article itself or in the cited articles. Using the data collection form, three authors (NO, HEW, and LCF) then conducted a pilot review on three articles to verify whether the reviewers reported the extracted data consistently. Subsequently, two researchers (NO, HEW) independently extracted the data from all included articles. When discrepancies existed, a third reviewer was consulted (LCF) and consensus was reached by discussion. For the MERSQI scores, a fourth independent reviewer (OtC) with expertise in using this tool was consulted when discrepancies existed.

Results

In total, 37 articles from fourteen different ITWs were included in our study. Six ITWs were situated in Scandinavia at: Aarhus University (Aarhus, Denmark), Karolinska University (Stockholm, Sweden; two different ITWs), Gothenburg University (Gothenburg, Sweden) and Linköping University (Linköping, Sweden). Eight ITWs were situated outside of Scandinavia at London University (London, UK; three different ITWs), Queens University (Belfast, UK), Curtin University (Perth, Australia), Monash University (Melbourne, Australia), Hull York Medical School (York, UK) and Edmonton University (Edmonton, Canada) (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Mackenzie et al. Citation2007; Morison and Jenkins Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Fallsberg and Hammar Citation2000; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Pelling et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Falk et al. Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Anderson et al. Citation2014; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014; Lindh Falk et al. Citation2015; McGettigan and McKendree Citation2015; Hallin and Kiessling Citation2016; Ericson et al. Citation2017).

Design and quality of the studies

Twenty studies used a combination of quantitative data (questionnaires with Likert scale) and qualitative data (semi-structured interviews, observations, and critical incident method) to study their research questions (Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Mackenzie et al. Citation2007; Morison and Jenkins Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014; McGettigan and McKendree Citation2015; Ericson et al. Citation2017). Seven studies used solely qualitative methods (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Fallsberg and Hammar Citation2000; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Falk et al. Citation2013; Hallin and Kiessling Citation2016). The MERSQI scores of the ten quantitative studies ranged between 7 and 13 (median 9) (Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Fallsberg and Hammar Citation2000; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Pelling et al. Citation2011; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Anderson et al. Citation2014; Lindh Falk et al. Citation2015). The median MERSQI score of 9 is relatively low, which is mostly based on the fact that the study design was often “single group cross-sectional or single group post-test only” or “single group pre- and posttest”, with no objective measurements of the study outcome but self-reported data and no reported validity of research tools.

Organization ITW

As the three universities in Scandinavia (Aarhus, Karolinska and Linköping University) were the first to design ITWs, many of the ITWs elsewhere in the world based the practical organization of their ITWs on the Scandinavian model (Supplemental Table 1). Therefore, the ITW programs described have common elements. For example, most rotations started with a half-day to a full day introductory session in which “goals” of the program were clarified and students got to know each other. Student teams in all ITW programs included, besides medical students, nursing students together with different combinations of students in physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work, dentistry, pharmacy, and speech language pathology (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Morison and Jenkins Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Anderson and Thorpe Citation2010; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014). The student groups responsible for patient care consisted of 2–12 students (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Morison and Jenkins Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Anderson and Thorpe Citation2010; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014). In all hospitals, the students who participated were in their final stages of studies and a high degree of self-reliance and autonomy was expected concerning patient care (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Morison and Jenkins Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Anderson and Thorpe Citation2010; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014). Most rotations in ITWs lasted for two to three weeks (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Anderson and Thorpe Citation2010; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014), except for the ITW rotation at Queens University which lasted six weeks. (Morison and Jenkins Citation2007) The learning objectives were not always specified, but in general consisted of (1) profession-specific learning goals (developing own professional role by practicing patient care) and (2) IP learning goals (developing knowledge of other professions and IP collaboration skills) (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Morison and Jenkins Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Anderson and Thorpe Citation2010; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014). IP learning goals were very often related to students’ profession-specific contributions to the clinical team, but also to participation in team activities, including general tasks such as “washing a patient”.

Some differences existed between the first Scandinavian wards and the wards developed elsewhere. First of all, Scandinavian ITWs were predominantly situated in orthopedic wards or in an emergency ward where students assessed orthopedic patients (Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2014) with the exception of one institution that was located in a rehabilitation ward (Carlson et al. Citation2011). Programs elsewhere in the world were situated in different types of wards, including: a geriatric unit (Carlson et al. Citation2011), (stroke) rehabilitation units (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Morison and Jenkins Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Anderson and Thorpe Citation2010; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014), orthopedic units (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002), a (acute/general) medical ward (Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013), emergency departments (Meek et al. Citation2013; Anderson et al. Citation2014; Hood et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014), in-patient hospice (Dando et al. Citation2012) and a pediatric nursing ward (Morison and Jenkins Citation2007).

Supervisors and faculty training

The students in the ITWs were supervised by both profession-specific tutors and tutors who supervised the IP team process (Freeth and Nicol Citation1998; Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Morison and Jenkins Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Jacobsen et al. Citation2009; Anderson and Thorpe Citation2010; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Carlson et al. Citation2011; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Sommerfeldt et al. Citation2011; Dando et al. Citation2012; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Hood et al. Citation2014; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014). The ITW supervisory team consisted of registered nurses and medical doctors, as they were most frequently present in the wards. Of all programs, six ITW programs (Supplemental Table 1: Monash University, London University, Royal London Hospital, Aarhus University, Karolinska University and Hull York Medical School) described training of the ITW supervisors. This faculty training usually consisted of one to two days of training in which the learning objectives of the ward and responsibilities of the supervisors towards promoting the IP learning process of students were discussed. In some cases, ITW supervisors mentioned that they found the work rewarding, but also stressful and more time-consuming than supervising non-ITW regular curriculum students (Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002).

Student learning outcomes

Many authors present pre- and post- rotation evaluations of students rating their own IP skills (Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Fallsberg and Hammar Citation2000; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Ericson et al. Citation2012; Lachmann et al. Citation2013). These seven pre- and post-rotation studies showed that students experienced a better understanding of what the other professions’ roles in medical care were after their ITW compared to before start of the ITW rotation. Four studies presented longitudinal follow-up data, assessed by using follow-up questionnaires including both open questions and Likert scales, on students having performed a rotation in an “interprofessional training ward” (Reeves et al. Citation2002; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Pelling et al. Citation2011). Reeves et al. (Citation2002), Hylin et al. (Citation2007), and Jakobsen et al. (Citation2011) saw that the enhanced effect on professional collaboration skills persisted one to four years after having participated in the rotation. Additionally, it was reported that students in their last year of study valued the high degree of autonomy and independence in which they functioned and performed patient care. Norgaard et al. (Citation2013) conducted the only study that compared students in an IPE placement (n = 239) with students in a non-ITW placement (n = 405) and showed that “interprofessional training improved students' perception of self-efficacy more than traditional training”. The majority of studies (27/32) achieved Kirkpatrick level 1 learning outcomes (satisfaction, perceptions) as these studies were based on students’ self-reported evaluations.

Assessment of student (learning) outcomes

In the ITW programs, both profession-specific and IP learning goals had to be evaluated and assessed. Twenty-two articles referred to the evaluation and assessment of profession-specific skills (Supplemental Table 2) (Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Ponzer et al. Citation2004; Hylin et al. Citation2007; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Hallin et al. Citation2009; Fallsberg and Hammar Citation2000; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Wilhelmsson et al. Citation2009; Jakobsen et al. Citation2010; Hylin et al. Citation2011; Jakobsen et al. Citation2011; Pelling et al. Citation2011; Lachmann et al. Citation2012; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Falk et al. Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2013; Norgaard et al. Citation2013; Lachmann et al. Citation2014; Lindh Falk et al. Citation2015; McGettigan and McKendree Citation2015; Hallin and Kiessling Citation2016). Four of the ITW rotations ended with a case presentation with all students (Supplemental Table 1: Hull York Medical School, Linköping University, Royal London Hospital and London University), which covered both assessment of the profession-specific and IP learning goals. At Karolinska University, students and supervisors had to provide each other with feedback on both profession-specific and IP tasks during reflective sessions. However, no standardized test for “interprofessional skills” was employed and the students often only evaluated their own progress rather than being objectively evaluated by either supervisors or peers. Several authors utilized evaluation tools to assess either the extent to which students were prepared for interprofessional learning (e.g. the Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale [RIPLS]) (Lachmann et al. Citation2013, Citation2014) or how they perceived their interprofessional learning environment (i.e. the Interprofessional Clinical Placement Learning Environment Inventory [ICPLEI]) (Anderson et al. Citation2014; Hood et al. Citation2014; Morphet et al. Citation2014).

Patient outcomes

Seven studies reported high patient satisfaction rates with no large impairment of hospital performance indicators as a result of the ITW programs (Supplemental Table 2). Meek et al. (Citation2013) showed no difference in several emergency department performance indicators (i.e. emergency department length of stay) between patients treated by an ITW student team and patients treated by non-ITW students. Only the median time to inpatient referral for admitted patients was significantly longer in ITW student-led beds compared with control beds (Meek et al. Citation2013). Hansen et al. (Citation2009) reported that having students performing clinical care in the “interprofessional training ward” was cost-effective and no difference was found in either complication rates or patient-reported quality of life between patients in an ITW and a normal ward. The authors attributed better IP communication and better communication with patients as factors that reduced the length of the hospital stay and early discharge of patients to rehabilitation facilities/home in an ITW compared to a regular ward (Hallin et al. Citation2011). One study did report that the increased number of people on the ward performing patient care did make the environment rather noisy, which was felt to be undesirable for very ill patients (Reeves and Freeth Citation2002). All seven studies reported that patients felt better informed in ITWs and that students often were motivated and enthusiastic (Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013). In 6/7 studies these ITW patient outcomes were reported in comparison to data obtained from patients in regular wards (Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Meek et al. Citation2013) and in 1/7 studies these patient outcomes were based on a questionnaire in only the ITW patient population (Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013).

Discussion

Interprofessional training wards in health profession education are increasingly seen as a promising approach towards IPE. While almost all ITW journal reports are from the current century, the near exponential growth in reports over the past two decades justifies targeted literature reviews in order to draw lessons for not only curricular and program improvement, but also training ward implementation. We have identified two recent reviews. One by Jakobsen et al. (Jakobsen Citation2016) focused on the pedagogy and organizational structure of ITWs in two Scandanavian countries and was, consequently, geographically limited; another was performed by Kent et al. (Citation2017) and focused on workplace-based IP interventions and explicitly excluded ITWs. We reviewed studies specifically focused on ITWs where student teams with at least one medical student and one student from another health profession had collaborative responsibilities in patient care and we had no geographical limitations for inclusion of literature.

We conclude that the ITWs that we included in this review, all over the world, are organized in a comparable fashion with groups of 2–12 health professions students providing patient care for a period of two to six weeks. In general, the group of students consists of a medical and a nursing student with different combinations of physiotherapy, occupational therapy, pharmacy and other health profession students. However, the type of clinical ward and the ways in which supervisors are trained differs widely.

A common theme encountered across the ITW studies was that organizing a clinical placement for all students from different professions at the same time proves to be a logistical challenge. Once a program has started, participating faculties from representative professional programs must ensure a more or less stable influx of students to make the rotation successful, which is why most ITW rotations had a relatively short duration of two weeks. Reeves et al. reports that a rotation of two weeks is too short, since students have only just gotten accustomed to the ward and each other before the rotation is over and, therefore, do not reach the full potential of working as collaborative partners (Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002). Also, an important unanswered question remains what type of ward would provide the optimal circumstances to ensure the best learning environment for students in ITW programs (e.g. which discipline and which level of complexity of patients).

Additionally, while IP team supervisors find the supervisory model of the ITW programs rewarding in terms of the benefits for health professions education, they also reveal that it is more time-consuming and mentally stressful, leaving less time for their own daily clinical activities (Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002). These findings highlight the need for supervisors to be well-prepared for their task in supervising ITW teams of students.

In general, students rate interprofessional learning opportunities in ITW programs highly. However, students in different programs indicated that the goals of the ITW were not always fully clear from the beginning. Reeves et al. noticed that medical students from the University of London sometimes saw the clinical placement as an opportunity to practice their profession-specific skills in becoming a house officer and did not always value the “team-activities” (Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002). It was reported that most students valued the “team-activities” to some extent, but they also felt that the time allotted for these activities should be limited in order to allow ample time for profession-specific practice. Wakefield et al. (Citation2006) reported that “no blurring of occupational boundaries should occur” since the different professions will always have different roles in medical care. According to the Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice (IPEC) it is important in the setting of IP practice to know one’s own roles and responsibilities as well as one’s boundaries (Washington DCIEC Citation2016).

It would be of value to have more detailed information on the exact training activities for students and the exact training of supervisors on the ITWs in order to perform an in-depth evaluation of how ITWs would function best in different health care systems and in different contexts. Additionally, specific organizational constraints, including legal issues, such as that the level of autonomy allowed in each ITW program might differ between jurisdictions, would be valuable to analyze. However, these in-depth details were often not mentioned in the currently evaluated articles. Future studies, by focusing on analyzing these specific practical data as this, might give a more accurate reflexion of the complexity of the issues encountered when designing an ITW.

Interprofessional training wards have shown promising results in short-term student learning outcomes and patient satisfaction rates, but these results were largely based on self-reported outcome measures by students and patients. In order to support cross-study analyses, future research might focus on assessing short- and long-term interprofessional skills of students more reliably and systematically using standardized tools by supervisors and peers instead of basing research outcomes of ITW programs largely on self-reported outcomes by students.

Despite the fact that we could not demonstrate that current ITW programs result in high levels of learning according to the Kirkpatrick scale, it is very interesting that, in total, seven studies showed that patient satisfaction rates were high in ITW programs (Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Hallin et al. Citation2011; Brewer and Stewart-Wynne Citation2013; Meek et al. Citation2013). Improving patient care in a health care system that is becoming increasingly complex is one of the main goals of ITW programs. Our goal in health care is to improve the patient experience, improve patients’ health and reduce healthcare costs. From those ITW studies that measured patient satisfaction, we see that improvements in patient experience were often reported (Freeth et al. Citation2001; Reeves and Freeth Citation2002; Reeves et al. Citation2002; Lindblom et al. Citation2007; Hansen et al. Citation2009; Hallin et al. Citation2011). From those studies that evaluated the financial impact of the units we saw, in general, a neutral effect, but more rigorously documenting cost-benefits would be an important step forward in showing the value of these programs. A daunting challenge that remains is that there are but few studies measuring the impact of IP training programs on collaborative practice or patient outcomes. We propose that, given the short-term nature of ITWs, it would be appropriate and most feasible to measure the patient outcomes that align with the focus of the training ward itself.

Our study showed that the methodological quality of most studies reporting on ITWs is relatively low according to the MERSQI scores. Most study outcomes were only tested in a single group without control group as comparison; most measurements of IP skills were self-reports; and usable, validated tools to objectively assess the short- and long-term interprofessional competencies of students were lacking. Additionally, several tools used, such as the RIPLS, have been critiqued for weak validity evidence (Mahler et al. Citation2015). While we had hoped to provide validity evidence for critical success factors in ITWs, the diversity of descriptions and relatively weak outcome measures as reported in the literature precluded us from drawing strong conclusions. Finally, we would like to point out that, besides the Scandinavian programs, where IPE is integrated into the curriculum for all students, many studies only show data on students who were specifically selected by the faculty to participate in the ITWs. This might have introduced bias as it is likely that more enthusiastic students will be asked to participate in pilot studies.

Recommendations

This study led us to develop recommendations for those interested in designing ITWs and planning its logistics, training of supervisors, student assessment and assessment of patient outcomes:

ITW programs would benefit from developing very clear profession- and IP-specific learning goals, to be clearly communicated to both students and supervisors before starting the rotation. Ideally, profession- and IP-specific learning goals would be balanced and students’ roles would be clearly specified in order to manage expectations.

All programs would benefit from structured supervisor training. We suggest that programs ensure that there are mechanisms in place in the institution to allow ITW supervisors to focus on their training-related duties and help them to better manage excess workload and stress.

Future research should focus on designing objective tools for supervisors and peers to assess short- and long-term interprofessional skills, patient satisfaction and relevant hospital outcomes.

Future studies may investigate which type of wards are most suitable for IP training and what is the ideal duration of an ITW rotation to develop IP skills, given likely logistical constraints and differences in context between countries.

Future studies may investigate ITW cost-effectiveness for the institution in both the short- and long-term.

Conclusions

In conclusion, ITW programs show promising results in patient satisfaction rates and student outcomes. However, future research should focus on assessing interprofessional qualities of students more reliably and systematically using standardized tools and should focus on which type of ITWs have most effective outcomes. IPE remains an imperative for future health professions education, despite challenges faced. ITWs are a promising step toward implementation of IPE in the clinical workplace.

Supplementary Table 1

Download MS Word (23.7 KB)Supplementary Table 2

Download MS Word (34.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Bianca Kramer, librarian at UMC Utrecht, and Dr. Whitaker Evans, librarian at UCSF, for their support in designing the literature search.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

N. Oosterom

N. Oosterom, MD, PhD student.

L. C. Floren

L. C. Floren, PharmD, MA, Associate Professor of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences.

O. ten Cate

O. ten Cate, PhD, Professor of Medical Education at the Center for Research and Development of Education.

H. E. Westerveld

H. E. Westerveld, MD PhD, Professor of Medical Education and director of Medical Undergraduate programs.

References

- Anderson A, Cant R, Hood K. 2014. Measuring students perceptions of interprofessional clinical placements: development of the Interprofessional Clinical Placement Learning Environment Inventory. Nurse Educ Pract. 14:518–524.

- Anderson ES, Thorpe L. 2010. Learning together in practice: an interprofessional education programme to appreciate teamwork. Clin Teach. 7:19–25.

- Barr H. 2002. Interprofessional Education: Today, Yesterday and Tomorrow. In: CAIPE_ UCftAoIE, editor.

- Brewer ML, Stewart-Wynne EG. 2013. An Australian hospital-based student training ward delivering safe, client-centred care while developing students' interprofessional practice capabilities. J Interprof Care. 27:482–488.

- Carlson E, Pilhammar E, Wann-Hansson C. 2011. The team builder: the role of nurses facilitating interprofessional student teams at a Swedish clinical training ward. Nurse Educ Pract. 11:309–313.

- Chen HC, Sheu L, O'Sullivan P, Ten Cate O, Teherani A. 2014. Legitimate workplace roles and activities for early learners. Med Educ. 48:136–145.

- D'Amour D, Oandasan I. 2005. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: an emerging concept. J Interprof Care. 19:8–20.

- Dando N, d’Avray L, Colman J, Hoy A, Todd J. 2012. Evaluation of an interprofessional practice placement in a UK in-patient palliative care unit. Palliat Med. 26:178–184.

- Ericson A, Lofgren S, Bolinder G, Reeves S, Kitto S, Masiello I. 2017. Interprofessional education in a student-led emergency department: a realist evaluation. J Interprof Care. 31:199–206.

- Ericson A, Masiello I, Bolinder G. 2012. Interprofessional clinical training for undergraduate students in an emergency department setting. J Interprof Care. 26:319–325.

- Falk AL, Hult H, Hammar M, Hopwood N, Dahlgren MA. 2013. One site fits all? A student ward as a learning practice for interprofessional development. J Interprof Care. 27:476–481.

- Fallsberg MB, Hammar M. 2000. Strategies and focus at an integrated, interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 14:337–350.

- Frank JR, Sherbino J, editors. 2015. CanMEDS 2015 physician competency framework. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

- Freeth D, Nicol M. 1998. Learning clinical skills: an interprofessional approach. Nurse Educ Today. 18:455–461.

- Freeth D, Reeves S, Goreham C, Parker P, Haynes S, Pearson S. 2001. 'Real life' clinical learning on an interprofessional training ward. Nurse Educ Today. 21:366–372.

- Gilbert JHY, Hoffman SJ. 2010. A WHO report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Allied Health 39:196–197.

- Hallin K, Henriksson P, Dalen N, Kiessling A. 2011. Effects of interprofessional education on patient perceived quality of care. Med Teach. 33:e22–e26.

- Hallin K, Kiessling A. 2016. A safe place with space for learning: experiences from an interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 30:141–148.

- Hallin K, Kiessling A, Waldner A, Henriksson P. 2009. Active interprofessional education in a patient based setting increases perceived collaborative and professional competence. Med Teach. 31:151–157.

- Hansen TB, Jacobsen F, Larsen K. 2009. Cost effective interprofessional training: an evaluation of a training unit in Denmark. J Interprof Care. 23:234–241.

- Hood K, Cant R, Leech M, Baulch J, Gilbee A. 2014. Trying on the professional self: nursing students' perceptions of learning about roles, identity and teamwork in an interprofessional clinical placement. Appl Nursing Res. 27:109–114.

- Hylin U, Lonka K, Ponzer S. 2011. Students' approaches to learning in clinical interprofessional context. Med Teach. 33:e204–e210.

- Hylin U, Nyholm H, Mattiasson AC, Ponzer S. 2007. Interprofessional training in clinical practice on a training ward for healthcare students: a two-year follow-up. J Interprof Care. 21:277–288.

- Jacobsen F, Fink AM, Marcussen V, Larsen K, Hansen TB. 2009. Interprofessional undergraduate clinical learning: results from a three year project in a Danish Interprofessional Training Unit. J Interprof Care. 23:30–40.

- Jakobsen F. 2016. An overview of pedagogy and organisation in clinical interprofessional training units in Sweden and Denmark. J Interprof Care. 30:156–164.

- Jakobsen F, Hansen TB, Eika B. 2011. "Knowing more about the other professions clarified my own profession". J Interprof Care. 25:441–446.

- Jakobsen F, Larsen K, Hansen TB. 2010. This is the closest I have come to being compared to a doctor: views of medical students on clinical clerkship in an Interprofessional Training Unit. Med Teach. 32:e399–e406.

- Kent F, Hayes J, Glass S, Rees CE. 2017. Pre-registration interprofessional clinical education in the workplace: a realist review. Med Educ. 51:903–917.

- Koens F, Mann KV, Custers EJ, Ten Cate OT. 2005. Analysing the concept of context in medical education. Med Educ. 39:1243–1249.

- Kvarnstrom S. 2008. Difficulties in collaboration: a critical incident study of interprofessional healthcare teamwork. J Interprof Care. 22:191–203.

- Lachmann H, Fossum B, Johansson UB, Karlgren K, Ponzer S. 2014. Promoting reflection by using contextual activity sampling: a study on students' interprofessional learning. J Interprof Care. 28:400–406.

- Lachmann H, Ponzer S, Johansson UB, Benson L, Karlgren K. 2013. Capturing students' learning experiences and academic emotions at an interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 27:137–145.

- Lachmann H, Ponzer S, Johansson UB, Karlgren K. 2012. Introducing and adapting a novel method for investigating learning experiences in clinical learning environments. Informat Health Soc Care. 37:125–140.

- Lindblom P, Scheja M, Torell E, Astrand P, Fellander-Tsai L. 2007. Learning orthopaedics: assessing medical students' experiences of interprofessional training in an orthopaedic clinical education ward. J Interprof Care. 21:413–423.

- Lindh Falk A, Hammar M, Nystrom S. 2015. Does gender matter? Differences between students at an interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 29:616–621.

- Mackenzie A, Craik C, Tempest S, Cordingley K, Buckingham I, Hale S. 2007. Interprofessional learning in practice: the student experience. Br J Occup Ther. 70:358–361.

- Mahler C, Berger S, Reeves S. 2015. The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS): A problematic evaluative scale for the interprofessional field. J Interprof Care. 29:289–291.

- Mann KV, McFetridge-Durdle J, Martin-Misener R, Clovis J, Rowe R, Beanlands H, Sarria M. 2009. Interprofessional education for students of the health professions: the "Seamless Care" model. J Interprof Care. 23:224–233.

- McGettigan P, McKendree J. 2015. Interprofessional training for final year healthcare students: a mixed methods evaluation of the impact on ward staff and students of a two-week placement and of factors affecting sustainability. BMC Med Educ. 15:185.

- Meek R, Morphet J, Hood K, Leech M, Sandry K. 2013. Effect of interprofessional student-led beds on emergency department performance indicators. Emerg Med Aust. 25:427–434.

- Morison S, Jenkins J. 2007. Sustained effects of interprofessional shared learning on student attitudes to communication and team working depend on shared learning opportunities on clinical placement as well as in the classroom. Med Teach. 29:450–470.

- Morphet J, Hood K, Cant R, Baulch J, Gilbee A, Sandry K. 2014. Teaching teamwork: an evaluation of an interprofessional training ward placement for health care students. Adv Med Educ Pract. 5:197–204.

- Norgaard B, Draborg E, Vestergaard E, Odgaard E, Jensen DC, Sorensen J. 2013. Interprofessional clinical training improves self-efficacy of health care students. Med Teach. 35:e1235–e1242.

- Pelling S, Kalen A, Hammar M, Wahlstrom O. 2011. Preparation for becoming members of health care teams: findings from a 5-year evaluation of a student interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 25:328–332.

- Ponzer S, Hylin U, Kusoffsky A, Lauffs M, Lonka K, Mattiasson AC, Nordstrom G. 2004. Interprofessional training in the context of clinical practice: goals and students' perceptions on clinical education wards. Med Educ. 38:727–736.

- Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM. 2007. Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA 298:1002–1009.

- Reeves S, Freeth D. 2002. The London training ward: an innovative interprofessional learning initiative. J Interprof Care. 16:41–52.

- Reeves S, Freeth D, McCrorie P, Perry D. 2002. 'It teaches you what to expect in future … ': interprofessional learning on a training ward for medical, nursing, occupational therapy and physiotherapy students. Med Educ. 36:337–344.

- Sommerfeldt SC, Barton SS, Stayko P, Patterson SK, Pimlott J. 2011. Creating interprofessional clinical learning units: developing an acute-care model. Nurse Educ Pract. 11:273–277.

- Thistlethwaite J, Kumar K, Moran M, Saunders R, Carr S. 2015. An exploratory review of pre-qualification interprofessional education evaluations. J Interprof Care. 29:292–297.

- Wahlstrom O, Sanden I, Hammar M. 1997. Multiprofessional education in the medical curriculum. Med Educ. 31:425–429.

- Wakefield A, Boggis C, Holland M. 2006. Team working but no blurring thank you! The importance of team work as part of a teaching ward experience. Learn Health Soc Care. 5:142–154.

- Washington DCIEC. 2016. Interprofessional Education Collaborative (2016). Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel.

- Wilhelmsson M, Pelling S, Ludvigsson J, Hammar M, Dahlgren LO, Faresjo T. 2009. Twenty years experiences of interprofessional education in Linkoping – ground-breaking and sustainable. J Interprof Care. 23:121–133.