ABSTRACT

Conversations and networks are essential for transforming academics’ teaching practices as learning experiences (Palmer 1993). Yet, there has been little research reporting academics’ informal conversations about teaching (Thomson and Trigwell 2018). Teachers will generally access small significant networks (Becher and Trowler 2001) for nuanced and personal issues relating to teaching and learning. Collaborative transnational projects provide fertile ground for unique conversations about Higher Education (HE) teaching (Thomson 2015), with the added value of cross-national perspectives. This study examines the conditions that help to create significant networks and conversations, based on collective autoethnographic reflections of the member of an Erasmus+ project, including five partner universities from four different countries. The results provide insights into how the project have afforded the generation and continuation of cross-national and interdisciplinary significant networks and how unique conversations have allowed for trust, relationships and common goals to develop, which add value beyond the individual level.

Introduction

People come into Higher Education (HE) from different routes and with different expectations, particularly around the tension between conducting research and teaching. This tension can be exacerbated by university priorities, and historically Rosser (Citation2003, 392) suggests that ‘rarely are new faculty members hired at research universities for their potential in teaching’. More recently, Wells et al. (Citation2019) highlight continuing confusion around the expectations around conducting research and teaching. In addition, Boyce et al. (Citation2019) contend that the development of teaching skills is given only cursory attention as part of doctoral study and when they begin their careers as academics (Baiduc, Linsenmeier, and Ruggeri Citation2016). Despite this, historically Smith (Citation1995) suggests that most university staff see teaching as their primary role, although most are not trained to be teachers (Jones Citation2008). This situation is further complicated by recent developments in the role of technology in HE teaching, particularly the sudden emergency and unstructured reliance on technology to facilitate HE teaching because of the COVID pandemic (Oliveira et al. Citation2021). Such changes require university educators to modify and expand their own professional practice (Hood and Littlejohn Citation2017) to keep pace with an increasingly pervasive and sophisticated digital era. The end result is that there ‘is a need to develop teaching in higher education’ (Pekkarinen, Hirsto, and Nevgi Citation2020, 13).

Although formal staff development opportunities to develop teaching are available to university staff, these can be limited and need to be fitted around competing demands (Sugrue et al. Citation2017; Sutherland Citation2018). Hence, informal opportunities within, and beyond, an individual’s own university can present unique opportunities to discuss effective teaching strategies. These opportunities can provide a context to discuss both conceptions of, and approaches to, teaching in HE; that is an individual’s beliefs and the strategies they adopt respectively (Englund, Olofsson, and Price Citation2017). Moving beyond formal provision for discussion also provides unique conditions to develop new sites for conversations about differing contexts (for example, pedagogic, cultural, disciplinary and curricular) to influence pedagogical changes in HE teachers – here including all other nomenclature for someone who teaches in HE, such as lecturer. This is particularly true when these teachers encounter challenges to their existing pedagogic beliefs provoked by contrasting, but deeply held, views, often backed up with academic theory and experience, of other HE teachers in their own and different disciplines. Arguably, an important, and perhaps unique, context for developing pedagogic practice is through transnational cooperation between higher education institutions (HEIs), rather than within single universities or an individual country. Collaborative transnational projects provide fertile ground for unique conversations about HE teaching with the added value of cross-national perspectives and exploring commonalities and differences across very different contexts. Further dimensions of complexity, and/or richness, are added when teachers in these collaborations are at different stages of their careers and have known each other for different lengths of time.

In exploring the impact of such factors, Masterman (Citation2016, 31) highlights the importance of conducting research using the ‘real-life practices of academics’. This paper responds by reporting on the lived experiences of a group of 15 HE teachers at different stages of their career (from Research Assistant to full Professor), from five university partners in four countries (Belgium, France, Ireland, Wales), working on a three-year Erasmus+ project [‘SHaring Open educational practices Using Technology For Higher Education’ (SHOUT4HE)]. One of the main project aims was to develop Open Educational Resources (OERs) and Open Educational Practices (OEPs) to reflect a growth in interest in their use in HE (Koseoglu and Bozkurt Citation2018; Tillinghast Citation2020). However, although not formally part of the project objectives, what organically emerged was a series of significant conversations (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009) reflecting on pedagogic practice in HE.

When the importance of these conversations was recognised, the team decided to formally explore them and developed a new research focus examining:

RQ1 – what circumstances produce opportunities for significant conversations about teaching in HE?

RQ2 – what are the best sites and settings for them to take place to challenge thinking about teaching in HE?

This paper responds to the suggestion that ‘there has been little research reported on academics’ informal conversations about teaching’ (Thomson and Trigwell Citation2018, 1536). It captures intra-team insights, focussing on, but not restricted to, how the conversational dynamics of the project have afforded the generation and continuation of cross-national and interdisciplinary significant networks and conversations (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009). In this context, we have adopted Aboelela et al.’s (Citation2007, 341) definition of interdisciplinary research, developed through a critical review of the literature, as ‘any study or group of studies undertaken by scholars from two or more distinct scientific disciplines’ – although we note some dispute such simple definitions (Huutoniemi, Bruun, and Hukkinen Citation2010).

This paper thus uses the lived experience of the participants, exemplified by quotes from the team members, to discuss their perceptions of the significance of these conversations and the best circumstances, sites and settings for them to take place to challenge thinking about, and potentially influence change in HE teaching.

Literature review

Significant networks

The potential for significant networks and the importance of improving HE teaching and learning is not a new concept. Palmer (Citation1993) identified conversations and networks on the topic of teaching as an effective method for transforming academics’ teaching and learning practices as well as the learning experiences of their students. Within the context of teaching and learning in HE, teachers will engage in a series of significant networks and subsequent significant conversations. It is within these arenas that teachers will share their ideas on teaching and learning with others and shape their future pedagogical decisions around the dialogue-taking place.

However, there are generally two networks, outlined by Becher and Trowler (Citation2001) that HE teachers will access and engage with conversations on their teaching and learning practices with. The first of these is outlined as the large network of resources, references and research that takes place about teaching and learning. The second, much smaller, network that teachers will participate in can be as limited as 10 people in total. This significant network will be utilised for more nuanced and personal issues relating to teaching and learning and it is within this arena that individuals will feel more comfortable to share. It is this ‘inclination to play safe’ (Becher and Trowler Citation2001, 127) that can limit the potential for true significance in an individual’s networks. That is why the research argues that expanding networks, across disciplines, institutions and countries, is important for taking greater risks in relation to HE teaching and learning practices. Arguably, this is the form of academic communication that is required for innovation and development of practice (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009).

Informal and formal learning

A particular focus of research has been maximising the effectiveness of formal learning opportunities and the subsequent informal conversations that take place because of this. Initially, Dewey (Citation1916) outlined the impact that both formal and informal learning can have on the development of the individual and the stark contrast between the two forms of academic development. These practices can still be widely viewed in HE today with formal workshops and quality assurance (Land Citation2001) being complemented by the everyday practices and events of the professional workplace that occur around the formal learning scenarios (Boud and Brew Citation2013; Eraut Citation2004). Recent research has aimed to demonstrate how the dual approach of formal and informal learning can enhance both teachers’ pedagogy and the learning of students (Gibbs Citation2013; Trigwell, Caballero-Rodriguez, and Han Citation2012; Thomson and Trigwell Citation2018). However, research has suggested that teachers will only engage with a limited number of academics and peers (Becher and Trowler Citation2001) and that there is a distinct link between positive experiences of significant networks and the number of people they will interact with (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009). This suggests a hesitance from teachers to consistently engage in these significant networks and conversations.

Factors for significance

There are a variety of factors that can impact on a teachers’ reluctance or enthusiasm to engage in a significant network or conversation. One significant factor is the amount of trust the individual has within the locality of the conversation (Roxå, Mårtensson, and Alveteg Citation2011). Moreover, levels of trust, the privacy of the conversation and the subsequent confidence and freedom of the teacher to talk openly have significant impacts on the networks and conversations that take place. This is referred to as ‘backstage behaviour’, which Goffman (Citation2000) recognised as the freedom felt by an individual when sharing in a private environment. This demonstrates the sensitive surroundings of significant networks in academia and may suggest why these arenas are often underutilised. There is an apparent and understandable hesitance to share from colleagues as they do not want disagreements and debates to have a consequential impact on their career or relationships within academia. Another key factor in the realm of significant networks is the level of intellectual engagement and shared interest among the networks’ participants. This is where teachers can learn, share and develop with other academics, resulting in new understandings and higher levels of university teaching (Steinert Citation2010). The most highly associated concept of this is ‘Communities of Practice’ (Wenger Citation1999, Citation2000), where a group with a common academic interest can engage in a mutual dialogue on the topic. This has the potential to increase the networks that an individual engages in from a local to international level.

Methods

The research adopted a collective autoethnographic approach to data collection, which ‘focuses on self-interrogation but does so collectively and cooperatively within a team of researchers’ (Chang, Ngunjiri, and Hernandez Citation2012, 21). More specifically, the team worked ‘in community to collect their autobiographical materials and to analyse and interpret their data collectively to gain a meaningful understanding’ (Chang, Ngunjiri, and Hernandez Citation2012, 23–24).

In this context, this paper draws on data collected from one online synchronous focus group involving 15 university staff, ranging from early career to full professor level, from five different European universities all participating in the SHOUT4HE Erasmus+ project. Given the range of experience in the team, it was important that each member of this international team held ‘equitable power in the research relationship … to negotiate personal dynamics and cultural elements, as well as the different goals, timelines, and kinds of knowledge that members of the team bring to the experience’ (Lapadat Citation2017, 22).

Although specifically convened as a one-off data collection event, the explicit focus was on reflecting over the many formal and informal conversations held during the first 18 months of the project and their own teaching careers – some just beginning, some long-established. Due to the reflexive nature of the research, the decision was made to allow participants to prepare in advance some reflections to the questions asked during the focus group. This presents both its benefits and challenges when allowing participants to know the nature and structure of the interview beforehand. The main benefit to this was the elimination of availability bias. In addition, instead of reflecting on what immediately comes to mind (Mamede et al. Citation2010), the participants were able to reflect on their experience in greater detail. This provided the research with richer, more descriptive, data as well as more specific examples of their experiences.

The focus group questions were posed by the project leader, as the most experienced researcher, but to acknowledge potential power relationships (Kennedy Citation2005) in the context of the project, the option was given for participants to submit any additional answers anonymously in the form of a survey after the virtual focus group had been conducted. Any such responses were then combined with the data gathered during the initial group discussion.

We were conscious of the potential for researcher bias, influenced by the prior relationships and knowledge of the participants that the researchers possess (Onwuegbuzie Citation2003). This is an ‘active’ form of researcher bias that can lead to bias being subconsciously during the data collection, data analysis or interpretation phases of the researching process. It is also important to note the added complexity of bias when considering the reflection and researching of the researcher/s own experiences and practice. One of the potential consequences of this is the enactment of confirmation bias, with the researchers having already created their own reflections and interpretations of the group significance as a network, also noted as a priori hypotheses (Greenwald et al. Citation1986). Typically, this will become more apparent during the interpretation stage of the researching process. To address this, the interpretation of data used triangulation of multiple researchers (inter-rater reliability), as well as multiple sources and theories (Merriam Citation1988; Patton Citation1990). This reduced the potential for chance associations being made and provides increased confidence and validity in the interpretations made by the researching team (Miles and Huberman Citation1984, Citation1994).

Given the widely geographically dispersed of participants across five countries, and the restrictions on travel due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, for data collection, it was necessary to convene a recorded online focus group. Nevertheless, synchronous online focus group discussions (SOFGDs) are a ‘well-established, valuable, mainstream qualitative research tool spanning across multiple fields of study’ (Woodyatt, Finneran, and Stephenson Citation2016, 741) and are a sound technique for conducting a focus group with participants from multiple different locations (Fielding, Raymond, and Blank Citation2016). They were enabled by the high level of synchronous technologies that can be easily accessed (Stewart and Shamdasani Citation2017). Such technologies mean that SOFGDs can be favourably compared with in-person interviews in developing rapport and disclosure (Jenner and Myers Citation2019). Indeed, SOFGDs ‘mirror in-person conversations where participants can effectively converse … and can bring forth similar high-quality data’ (Greenspan et al. Citation2021, 85). Further benefits are outlined by Hanna and Mwale (2017, 260), who argue that remote interviews offer a public, yet private, space which can be ‘a more empowered experience for the interview participant’, which thus reduce concerns about power imbalances (Beauchamp et al. Citation2021). Finally, as the transnational research team had used online meetings often as a forum for discussion, it was a familiar format for all participants of the project. This allowed for a sense of openness and comfortability in engaging in a semi-structured focus group. Ethical informed consent was gained in accordance with university protocols. The meeting was recorded and transcribed for later analysis.

To develop trustworthiness, the research team used a process of thematic analysis outlined by Nowell et al. (Citation2017). Three members of the research team undertook a comprehensive reading and re-reading of the data to ensure a familiarity with the content and a certainty of the themes that have been identified (Rice and Ezzy Citation1999). These initial ideas were triangulated between the three researchers to ensure a level of inter-coder reliability (Castleberry and Nolen Citation2018). This consolidation led to the generation (Braun and Clarke Citation2019; Braun, Clarke, and Hayfield Citation2019) of the initial set of agreed codes and themes. Once themes were agreed, two of the same members of the team conducted a final re-analysis of the data. As a form of member checking (Côté and Turgeon Citation2005), the final themes were then agreed with the whole team through peer debriefing and a team consensus, including the proposed final model discussed later. The results are presented below with the quotations of participants included alongside the initial findings of the analysis process to maintain validity and credibility by showing the interpretations of the data alongside the raw data itself (Patton Citation2002).

Results

Much existing research has focused on conversations between partners in the same or local institutions, normally in the same country. This project suggests that when these conversations happen across different institutions and countries, they can still be significant and reinforce and extend more localised conversations. The transnational nature of collaboration provided new opportunities to develop significant networks and conversation based around a common interest in teaching and learning, but also, importantly in making a conversation significant, ‘widening the context from the national to the international’ (Kiki). It is important to note that we were not attempting to assess the impact of these conversations on subsequent teaching and learning. Rather, reflecting our research questions, we wanted to explore what the best circumstances and sites/settings were to facilitate significant conversations, which challenge thinking about teaching in HE. As such, the results foreground thoughts on how conversations can help identify, and make explicit, ideas that had previously been implicit and unspoken.

Localities

A key finding is that the setting of conversations was an important factor in them becoming significant. More specifically, opportunities to visit another HE institution in another country were fundamental. The opportunity to see both formal and informal spaces and how they were used, especially by students, was a powerful influence. As Linda explained:

the travelling and the visiting and seeing the different institutions and how they’re set up and how they work it on a daily basis, the students moving around and that type of thing that’s a factor for me but it has meant that it has become a significant network.

you can recognise some expertise as we are all around this virtual table of different expertise and roles within our universities and it’s good to see how a lot of colleagues can support my question or how can I start a conversation with a particular person around this table. (Henric)

Relationships

It is important, however, that these conversations, in a variety of locations, continue over time as they ‘kind of build-up on the things that you’ve already been talking about and I would mention safety that it’s kind of a non-judgemental mutually supportive sort of relationship’ (Kiki). As Ffion explained, this becomes

a relationship, I would say a mutually dependent relationship between the affective and the effective and I think that has to be the case, in order to be effective, we need to be affective with each other and vice versa.

a sense of humour, we don’t take ourselves too seriously, we get the job done but there’s also – and I think this is really important in any trusted networks – that there’s a bit of sort of common understanding, a bit of humour, a bit of light-heartedness.

seeing the enthusiasm and the motivation of colleagues all here present and the way how they can transfer this motivation and energy to others, makes things more doable and more realistic and encourages the others. (Olivia)

I think that exchanges are significant when both people have a question, … There has to be a question on both sides and I think that’s what makes it significant when everyone needs to get something out of the exchange.

Trust – flat hierarchy

It emerged as important, however, that affective relationships are more easily built outside of individual institutional hierarchies. A unique feature of a multinational project was the perceived ‘flat hierarchy’ (Linda) as a result of the fact that

we don’t have any institutional relationships with each other, you know, … there aren’t any sort of formal hierarchies so the conversations tend to be quite honest and I think it gives you that confidence to say what I’m doing is okay … and that ability to share with others as well is important. (Ffion)

very honest about [your] own practices whether they’re good or bad so, you know, learning from the failures as well as learning from the successes and it’s related, of course, to trust. If you don’t trust the people that you’re talking to, you’re not going to be very honest with them and I think that level of honesty is really important if progress is to be made.

Common goals

Trust was also perceived to be built by working towards ‘common goal’. In the context of this team, these were provided by the deliverables of the project, which provided a direction and drive to conversations within the group. This made them significant in terms of achieving specific objectives, but significance was also identified in terms of teaching, which can become the spark for significant or meaningful discussion between colleagues.

Getting a job done, be it large or small-scale, within the project or teaching, was also an important factor as it provides ‘maybe a condition or a driver, in my opinion it’s a sense of urgency, something that triggers the question, the conversation’ (Henric). This was qualified, however, by Linda who noted the importance of the ‘idea of timeliness, … so you have maybe not so much urgency, but for me timeliness’. Nevertheless, urgency was provided by the shared project deliverables, which were also important in making conversations significant as:

I think the whole idea of having common goals really helps in creating a significant network, the common goals are defined in this case by the project but it could be by something else, it could be by, you know, shared teaching by discipline. (Sharon)

One thing that the project has done for me has made me engage more conversations with more colleagues in different disciplines at the university … it has certainly encouraged me to step out of the general circuits of colleagues that I see in my own department or in very closely related departments to talk to people who are in maths or who are in physics or who are in engineering and different areas.

This was also significant within the project team, as Sara highlighted: ‘I’m talking about amongst ourselves. It’s come from we’re all in different contexts, different disciplines so that’s been enriching’.

Interdisciplinarity – new lenses

The project team worked across many different disciplines, including education, health and human sciences, applied science and arts, and modern languages and applied linguistics. These interdisciplinary lenses led to conversations which were ‘very useful and very insightful and allow you to think about things in a slightly different way or taking a different perspective’ (Ffion). While such conversations may be imposed in a project context by the choice of partners, it is not just the initial insight gained visiting another university, in another country, that is important, but the fact that the openness to such conversations is transferred back to a local context on return to the home campus. For instance, Sara noted that ‘we’re all in different contexts, different disciplines so that’s been enriching’. Another important affordance of these diverse conversations was the exposure to

a lot of colleagues with different types of expertise and … we don’t have in our institution people like [name of colleagues]. We don’t get in touch with them really or they just don’t exist and so it’s really interesting for us to see how other institutions work and what these specialists bring to higher education and how you can interact with them. (Janea)

Informal from formal

The data suggest that valuable informal opportunities are often generated from formal contexts, both in the lecture room and in staff development. Indeed, the formal settings were more valued for what happened after them, than during. This was summed up by Ffion who described how

Very often the more detailed conversations I think tend to happen informally rather than formally at meetings. So, you know, an issue comes up at a meeting or an incident comes up at a meeting and then there’s a follow up in terms of a longer conversation with the relevant colleagues over coffee or even, you know, another break-out meeting from that.

In addition to formal meetings leading to significant conversations, formal teaching sessions could also provide the stimulus for important informal discussions. Sara suggested that this can be

informally when we come out of class … so when we’ve all seen our group I would say we come out of class and say oh how did that go? … [and] … it’s quite often in our staff room at lunchtime or by the photocopier machine, some informal discussions about the teaching and learning that went on.

The key feature of all of these significant conversations, informal but stimulated by formal events, was summed up by Sharon’s view that ‘I think everyone has mentioned things spontaneously arising’. Although many examples were provided which reflected this could be summed up as ‘informal in-house’ (Sara), we have already seen that different localities provide more geographically diverse contexts.

Expanding networks

Janet described how the network of the research team had allowed her to ‘with more colleagues in different disciplines at the university … it has certainly encouraged me to step out of the general circuits of colleagues that I see in my own department or in very closely related departments’. This is one of the key findings of the research and the importance of expanding networks and creating further significant networks. It is crucial to developing teaching practices and challenging existing ideas of effective practice. However, as already outlined, the dynamics of a significant network and significant conversations, there are a range of factors can have an impact on just how significant this is. It links back to the role of trust, confidence and privacy within the context of the conversations (Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009). These factors are important to the individuals concerned, but must be placed in the hands of others to allow for significant networks to be built. In the context of the research team in question, levels of trust were pre-existing from previous working relationships. However, the foundations of trust and confidence were not in place and widespread beforehand. Therefore, the conversations and work of the SHOUT4HE team can be viewed as a significant network that goes beyond the limitations of discipline, department, institution or country. Therefore, it can be argued that research projects similar to these can be the arenas for significant conversations and a broadening and expanding of individual networks. As mentioned, the research team has a range of experience and roles within their respective HEIs (Research Assistant to Full Professor). This suggests that the use of a common interest, such as a research project, can break down barriers of hierarchy and ‘titles’ within academia to lead to fair, engaging and ‘significant’ conversations for all involved.

Discussion

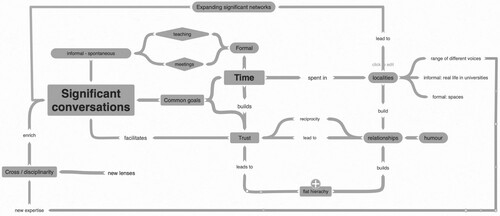

The aim of this study was to explore what contexts produce opportunities for significant conversations about teaching in HE and to identify the best conditions, sites and settings for them to take place to challenge thinking about, and potentially influence change. The data suggest that a range of factors can have an impact on the significance of the network and the significant conversations, whether formal or informal, that take place. We will examine each in turn leading to the development of a model of context and influences of significant conversations in developing teaching in HE.

Perhaps the most central theme, and potentially impacting on all others, focused on dimensions of time in many forms.

Time

The first aspect of time is related to time spent in different locations. Previous research (Becher and Trowler Citation2001; Roxå and Mårtensson Citation2009) has suggested that teachers prefer to talk seriously to ‘local’ colleagues. Our data, however, suggest that moving physically away from local settings and colleagues in the same disciplines can open discursive, cross-disciplinary conversations, which lead to them being valued by participants. This idea of place-responsiveness resonates with the importance of place in other areas of research, such as children’s outdoor play. Dolan (Citation2016, 53) encapsulates this by explaining that ‘Place is therefore more than a physical environment as it comes to have meaning through people’s interactions with it. Places and spaces are socially constructed’. While this could also apply to local places to the participants, we suggest that time spent in novel settings, with geographic and cultural diversity, can add further significance to networks. As Hawkins (Citation2014, 91) explains, when discussing ontologies of place in education, ‘The distinctive nature and features of each place where meaning making occurs shape what is and can be learned within it’. We, therefore, concur with Fettes and Judson’s (Citation2010, 123) contention that ‘place is seen as a valuable resource for human development’.

It is not, however, the location on its own that leads to significance. Rather, it is also the time spent in interactions with others in the network, combined with a flat hierarchy and growing trust, established through, for instance, reciprocity and humour. This seems to resonate with Goffman’s (Citation2000) concept of ‘backstage behaviour’, which allows teachers to act within private settings, where they feel comfortable to share and confident within these familiar surroundings of team members. Another temporal element which facilitates backstage behaviour is experiencing both formal and informal time with a group in varied settings. Indeed, it is these informal practices and experiences, that happen in the day-to-day, that can be the instigator for meaningful and transformative conversations when placed in formal settings.

In some respects, both locations and participants can be controlled by those taking part in this type of activity. Our data suggest that another important temporal factor is timeliness, which is much harder to control. We regard timeliness as the fluctuation in significance depending on individual. This is best explained by Ffion who stated that

it’s [significance] not always a linear process, so we don’t move from being less significant to being really significant and keep it at that level of significance. … at different periods of time in your teaching career this project and these people will be more significant or less significant depending on what you’re doing within your own context. And I think that’s really important because it allows for other significant networks that you have also to come in and out of your professional life.

Another factor which cannot necessarily be controlled is the serendipity of previously unknown participants gelling through a process of ‘throwntogetherness’, a haphazard social and physical propinquity (Pierce, Martin, and Murphy Citation2011, 58).

Another temporal aspect of developing significant conversations is that time cannot be compressed as summarised by Sharon:

I think you need a certain amount of time, that’s not compressible. That you need regular meetings, … but you also need time to process what people are doing, to put it into context yourself and this is really not compressible I think. You can’t just line up all the hours that people have spent and push them all together and say we’ll do it in six months, you really need the longer time to think about it. (Sharon)

Limitations and future research

The research is limited to focusing on the experiences and conversations of one transnational project team within a three-year project, although it did reflect the lived reality of many years before the pandemic. We acknowledge that the team may have been already predisposed to conversations about teaching, but suggest this may reflect a wider characteristic of all HE teachers. The data collection was also limited to one virtual focus group due to the ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, therefore, further research on a larger scale would be beneficial to determine the importance of the study’s findings beyond being isolated incidents in time. More specifically, a future study could explicitly explore the longevity of such networks to ascertain how they can become embedded in university practices to ensure significant conversations continue within and between universities. In addition, further study could seek evidence of the impact of these conversations upon the quality of teaching, and/or their potential contribution to innovation and changing practices, which was beyond the scope of the current study.

Conclusions

We conclude that significant conversations are situated and contextualised by time, location, trust, in formal and informal meetings in cross-disciplinarity teams. Gibbs, Knapper, and Piccini (Citation2007, 2) suggest that ‘new forums need to be put in place to build a community of practice about teaching’. The SHOUT4HE Erasmus+ research project has provided the research team with the opportunity to discuss and connect through common goals and shared interests. Arguably, the conditions of the project have allowed for relationships to grow over time and for significant conversations to take place naturally, both within formal and informal settings, in four different countries. Therefore, we suggest that transnational, interdisciplinary projects like these have great potential in developing significant conversations and networks and are worthy of further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aboelela, Larson E, S. Bakken, O. Carrasquillo, A. Formicola, S. A. Glied, J. Haas, and K. M. Gebbie. 2007. “Defining Interdisciplinary Research: Conclusions from a Critical Review of the Literature.” Health Services Research 42 (1): 329–346. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00621.x.

- Baiduc, R., R. A. Linsenmeier, and N. Ruggeri. 2016. “Mentored Discussions of Teaching: An Introductory Teaching Development Program for Future STEM Faculty.” Innovative Higher Education 41 (3): 237–255. doi:10.1007/s10755-015-9348-1.

- Beauchamp, G., M. Hulme, L. Clarke, L. Hamilton, and J. A. Harvey. 2021. “‘People Miss People’: A Study of School Leadership and Management in the Four Nations of the United Kingdom in the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Educational Management, Administration and Leadership 49 (3): 375–392. doi:10.1177/1741143220987841.

- Becher, T., and P. Trowler. 2001. Academic Tribes and Territories. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Boud, D., and A. Brew. 2013. “Reconceptualising Academic Work as Professional Practice: Implications for Academic Development.” International Journal for Academic Development 18 (3): 208–221. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2012.671771.

- Boyce, B. A., J. L. Lund, G. Napper-Owen, and D. Almarode. 2019. “‘Doctoral Students’ Perspectives on Their Training as Teachers in Higher Education.’.” Quest 71 (3): 289–298. doi:10.1080/00336297.2019.1618065.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “‘Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, and N. Hayfield. 2019. “‘A Starting Point for Your Journey, Not a Map’: Nikki Hayfield in Conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke About Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1–22. doi:10.1080/14780887.2019.1670765.

- Castleberry, A., and A. Nolen. 2018. “Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Research Data: Is It as Easy as It Sounds?” Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 10 (6): 807–815. doi:10.1016/j.cptl.2018.03.019.

- Chang, H., F. Ngunjiri, and K. C. Hernandez. 2012. Collaborative Autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: Taylor & Francis.

- Côté, L., and J. Turgeon. 2005. “Appraising Qualitative Research Articles in Medicine and Medical Education.” Medical Teacher 27: 71–75. doi:10.1080/01421590400016308.

- Dewey, J. 1916. Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: Macmillan.

- Dolan, A. M. 2016. “Place-based Curriculum Making: Devising a Synthesis Between Primary Geography and Outdoor Learning.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 16 (1): 49–62. doi:10.1080/14729679.2015.1051563.

- Englund, C., A. D. Olofsson, and L. Price. 2017. “Teaching with Technology in Higher Education: Understanding Conceptual Change and Development in Practice.” Higher Education Research and Development 36 (1): 73–87. doi:10.1080/07294360.2016.1171300.

- Eraut, M. 2004. “Informal Learning in the Workplace.” Studies in Continuing Education 26 (2): 247–273. doi:10.1080/158037042000225245.

- Fettes, M., and G. Judson. 2010. “Imagination and the Cognitive Tools of Place-Making.” The Journal of Environmental Education 42 (2): 123–135. doi:10.1080/00958964.2010.505967.

- Fielding, N., M. L. Raymond, and G. Blank. 2016. The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Gibbs, G. 2013. “Reflections on the Changing Nature of Educational Development.” International Journal for Academic Development 18 (1): 4–14. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2013.751691.

- Gibbs, G., C. Knapper, and S. Piccini. 2007. “The Role of Departmental Leadership in Fostering Excellent Teaching.” In Practice 13: 1–4. doi:10.1177/0013161X17718023.

- Goffman, E. 2000. Jaget och Maskerna [The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life]. Stockholm: Prisma.

- Greenspan, S., L. Kelsey, S. Gordon, A. Whitcomb, and A. Lauterbach. 2021. “Use of Video Conferencing to Facilitate Focus Groups for Qualitative Data Collection.” American Journal of Qualitative Research 5 (1): 85–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/10813.

- Greenwald, A. G., A. R. Pratkanis, M. R. Leippe, and M. H. Baumgardner. 1986. “Under What Conditions Does Theory Obstruct Research Progress?” Psychological Review 93 (2): 216–229. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.93.2.216.

- Hawkins, M. R. 2014. “Ontologies of Place, Creative Meaning Making and Critical Cosmopolitan Education.” Curriculum Inquiry 44 (1): 90–112. doi:10.1111/curi.12036.

- Hood, N., and A. Littlejohn. 2017. “‘Knowledge Typologies for Professional Learning: Educators’ (Re)generation of Knowledge When Learning Open Educational Practice.” Educational Technology Research and Development 65 (6): 1583–1604. doi:10.1007/s11423-017-9536-z.

- Huutoniemi, Klein J. T., H. Bruun, and J. Hukkinen. 2010. “Analyzing Interdisciplinarity: Typology and Indicators.” Research Policy 39 (1): 79–88. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2009.09.011.

- Jenner, B., and K. Myers. 2019. “Intimacy, Rapport, and Exceptional Disclosure: A Comparison of in-Person and Mediated Interview Contexts.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 22 (2): 165–177. doi:10.1080/13645579.2018.1512694.

- Jones, A. 2008. “Preparing new Faculty Members for Their Teaching Role.” New Directions for Higher Education 2008 (143): 93–101. doi:10.1002/he.317.

- Kennedy, A. 2005. “Models of Continuing Professional Development: A Framework for Analysis.” Journal of In-Service Education 31 (2): 235–250. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.929293.

- Koseoglu, S., and A. Bozkurt. 2018. “An Exploratory Literature Review on Open Educational Practices.” Distance Education 39 (4): 441–461. doi:10.1080/01587919.2018.1520042.

- Land, R. 2001. “Agency, Context and Change in Academic Development.” International Journal for Academic Development 6 (1): 4–20. doi:10.1080/13601440110033715.

- Lapadat, J. C. 2017. “Ethics in Autoethnography and Collaborative Autoethnography.” Qualitative Inquiry 23 (8): 589–603. doi:10.1177/1077800417704462.

- Mamede, S., T. van Gog, K. van den Berge, R. Rikers, J. van Saase, C. van Guldener, and H. Schmidt. 2010. “Effect of Availability Bias and Reflective Reasoning on Diagnostic Accuracy Among Internal Medicine Residents.” JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 304 (11): 1198–1203. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1276.

- Masterman, E. 2016. “Bringing Open Educational Practice to a Research-Intensive University: Prospects and Challenges.” Electronic Journal of E-Learning 14 (1): 31–43.

- Merriam, S. 1988. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1984. “Drawing Valid Meaning from Qualitative Data: Toward a Shared Craft.” Educational Researcher 13 (5): 20–30. doi:10.2307/1174243.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 1–13. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Oliveira, G., J. Grenha Teixeira, A. Torres, and C. Morais. 2021. “An Exploratory Study on the Emergency Remote Education Experience of Higher Education Students and Teachers During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” British Journal of Educational Technology 52 (4): 1357–1376. doi:10.1111/bjet.13112.

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J. 2003. “Expanding the Framework of Internal and External Validity in Quantitative Research.” Research in the Schools 10 (1): 71–89.

- Palmer, P. J. 1993. “Good Talk About Good Teaching – Improving Teaching Through Conversation and Community.” Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 25 (6): 8–13. doi:10.1080/00091383.1993.9938466.

- Patton, M. 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Patton, M. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pekkarinen, V., L. Hirsto, and A. Nevgi. 2020. “The Ideal and the Experienced: University Teachers’ Perceptions of a Good University Teacher and Their Experienced Pedagogical Competency.” International Journal of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education 32 (1): 13–30.

- Pierce, J., D. G. Martin, and J. T. Murphy. 2011. “Relational Place-Making: The Networked Politics of Place.” Transactions - Institute of British Geographers 36 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00411.x.

- Poole, G., I. Iqbal, and R. Verwoord. 2019. “Small Significant Networks as Birds of a Feather.” International Journal for Academic Development 24 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2018.1492924.

- Rice, P. L., and D. Ezzy. 1999. Qualitative Research Methods: A Health Focus. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Rosser, V. J. 2003. “Preparing and Socializing New Faculty Members.” Review of Higher Education 26 (3): 387–395. doi:10.1353/rhe.2003.0004.

- Roxå, T., and K. Mårtensson. 2009. “Significant Conversations and Significant Networks – Exploring the Backstage of the Teaching Arena.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (5): 547–559. doi:10.1080/03075070802597200.

- Roxå, T., K. Mårtensson, and M. Alveteg. 2011. “Understanding and Influencing Teaching and Learning Cultures at University: A Network Approach.” Higher Education 62 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9368-9.

- Smith, R. 1995. “Reflecting Critically on Our Efforts to Improve Teaching and Learning.” In To Improve the Academy, edited by E. Neal, 5–25. Stillwater, OK: New Forums Press.

- Steinert, Y. 2010. “Faculty Development: From Workshops to Communities of Practice.” Medical Teacher 32 (5): 425–428. doi:10.3109/01421591003677897.

- Stewart, D. W., and P. Shamdasani. 2017. “Online Focus Groups.” Journal of Advertising: Themed Issue - Methodology in Advertising Research 46 (1): 48–60. doi:10.1080/00913367.2016.1252288.

- Sugrue, C., T. Englund, T. Drydal Solbrekke, and T. Fossland. 2017. “Trends in the Practices of Academic Developers: Trajectories of Higher Education?” Studies in Higher Education 43 (12): 2336–2353. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1326026.

- Sutherland, K. 2018. “Holistic Academic Development: Is It Time to Think More Broadly About the Academic Development Project?” International Journal for Academic Development 23 (4): 261–273. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2018.1524571.

- Thomson, K. 2015. “Informal Conversations About Teaching and Their Relationship to a Formal Development Program: Learning Opportunities for Novice and Midcareer Academics.” International Journal for Academic Development 20 (2): 137–149. doi:10.1080/1360144X.2015.1028066.

- Thomson, K., and K. Trigwell. 2018. “The Role of Informal Conversations in Developing University Teaching?” Studies in Higher Education 43 (9): 1536–1547. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1265498.

- Tillinghast, B. 2020. “Developing an Open Educational Resource and Exploring OER-Enabled Pedagogy in Higher Education.” IAFOR Journal of Education 8 (2): 159–174. doi:10.22492/ije.8.2.09.

- Trigwell, K., K. Caballero-Rodriguez, and F. Han. 2012. “Assessing the Impact of a University Teaching Development Programme.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 37 (4): 499–511. doi:10.1080/02602938.2010.547929.

- Wells, P., K. N. Dickens, J. S. McBraer, and R. E. Cleveland. 2019. “‘If I Don’t Laugh, I’m Going to cry’: Meaning Making in the Promotion, Tenure, and Retention Process: A Collaborative Autoethnography.” Qualitative Report 24 (2): 334–351.

- Wenger, E. 1999. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E. 2000. “Communities of Practice and Social Learning Systems.” Organization 7 (2): 225–246. doi:10.1177/135050840072002.

- Woodyatt, C. R., C. A. Finneran, and R. Stephenson. 2016. “In-Person Versus Online Focus Group Discussions: A Comparative Analysis of Data Quality.” Qualitative Health Research 26 (6): 741–749. doi:10.1177/1049732316631510.