ABSTRACT

European Union (EU) agencies are known to have a high risk of capture by regulated business interests. To limit this risk, agencies try to involve a diverse set of stakeholders. One way of doing so, is to install advisory councils (ACs): permanent bodies with a fixed number of stakeholders selected by the agency. Current scholarship has mainly studied whether stakeholders’ access to ACs is biased towards business interests. However, it remains unknown whether the ACs functioning might also be biased. This research note presents a strategy to go beyond access and look inside the ACs. By examining how members perceive the councils, its meetings and the discussions therein, it explores whether the councils’ functioning contributes to more balanced interest representation. We illustrate that although the councils’ members are willing to prioritize seeking consensus over defending their own interests, finding this consensus proves difficult due to asymmetries in resources, thus stressing the need for a better understanding of bias. We end with proposing further qualitative approaches to study bias of advisory bodies in the future.

Introduction

Interest group lobbying in regulation is an increasingly studied area of research. What particularly sparks academic interest in this regard is the closeness of regulators and regulatees (i.e. those actors that are affected by regulation, such as businesses). This closeness is necessary for regulators to gain information about markets, current developments in industries but also information about the effectiveness of regulation and the compliance of regulatees. Yet, this closeness can also create interdependencies, in which the regulator becomes dependent on regulatees’ information, which may be coloured by their interests or may tell only one part of the story. This may then result in regulation that favours the interests of regulatees, rather than the interests of consumers or other end-users. This bias towards business interests thus poses a risk for regulators and for regulation more generally.

A major way of limiting bias is to ensure involvement of a more heterogeneous set of stakeholders (Klüver Citation2012; Lowery et al. Citation2015). If regulators not only get information from regulatees but also from other stakeholders, the regulator should gain a more representative image of the problems at hand. One way to realize this is to install consultation instruments such as advisory councils (ACs) (Arras and Braun Citation2017; Beyers and Arras Citation2019). These are permanent bodies within the agency, in which a limited number of stakeholders, selected by the agencies, hold a seat for a longer period of time (Binderkrantz Citation2012; Fraussen, Beyers, and Donas Citation2015; Gornitzka and Sverdrup Citation2015; Rasmussen and Gross Citation2015). Agencies may use ACs to balance interest representation and as such counterbalance the structural predominance of regulated business interests (Arras and Braun Citation2017; Beyers and Arras Citation2019).

Research has highlighted that agencies have made efforts to demonstrate that their policy outputs reflect societal considerations (Busuioc and Jevnaker Citation2022). At the same time, however, studies have also demonstrated that the composition of advisory councils’ membership is dominated by business interests (Arras and Braun Citation2017; Perez-Duran 2019; Pérez-Durán and Bravo-Laguna Citation2019; Wood Citation2018). Although some agencies are obliged to appoint members to represent a diverse set of interests in balanced proportions, it is still unclear to what extent the processes within the advisory councils are balanced. Indeed, even if access to the councils is (relatively) balanced, members might not have equal ‘voice’ in these councils (also see Busuioc and Jevnaker Citation2022).

This research note develops a qualitative strategy to understand bias beyond access, by exploring whether the functioning of ACs in EU agencies contributes to a more balanced interest representation. Scholarship has studied bias beyond access within the management boards of EU agencies (e.g. Buess Citation2015; Pérez-Durán Citation2019), but not yet in advisory councils. Yet, understanding how such advisory councils function is equally crucial as these bodies advise the agency directly on upcoming regulation, regulatory oversight and provide a selective group of stakeholders direct access to the agency head. Our contribution offers a framework to qualitatively study bias in advisory councils, moving beyond merely studying access (Arras and Braun Citation2017; Busuioc and Rimkutė Citation2020; but also see Busuioc and Jevnaker Citation2022).

To this end, we first draft a framework through which we can understand bias in ACs and then apply this framework to the ACs of the most powerful EU regulators:Footnote1 the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs). Based on thirteen in-depth interviews with council members, we illustrate that the councils’ functioning is largely favouring business interests over consumer interests. Although council members attempt to find a reasoned consensus, consumer groups cannot always contribute due to a general lack of insider-information, financial and organizational resources. Our findings show that although members are willing to seek consensus, asymmetries in members’ capabilities prevent them from effectively doing so. Despite the diverse composition of the ACs, their functioning tends to be biased in favour of regulated business interests. Based on these first findings, we propose avenues for future research to empirically study bias in a more meaningful manner.

Advisory councils as a means to limit bias

Stakeholder involvement has become an important aspect of EU agencies’ governance structures (Ayres and Braithwaite Citation1992; Grabosky Citation2013). As EU agencies are independent bodies with far-reaching regulatory competences, their engagements with stakeholders fulfil informational needs, ensure compliance and safeguard a credible reputation (Borrás, Koutalakis, and Wendler Citation2007; Braun Citation2012; Busuioc and Lodge Citation2016; Coglianese, Zeckhauser, and Parson Citation2004; Furlong and Kerwin Citation2004).

However, close involvement of stakeholders may threaten agencies’ autonomy and can cause regulatory capture: policy outputs that systematically favour business interests at the disadvantage of general interests (Carpenter and Moss Citation2013; Stigler Citation1971). Agencies are sensitive to such capture due to their constant need for expert information. Such information can be supplied by stakeholders with an extensive knowledge about problems and solutions for issues in a particular sector (Bouwen Citation2002; Coglianese, Zeckhauser, and Parson Citation2004). Considering the agencies’ dependency on this expertise, there is a risk of ‘closeness’ between stakeholders (in particular regulated business interests which possess such expertise) and the agency (Baxter Citation2011; Coglianese, Zeckhauser, and Parson Citation2004; Tsingou Citation2010).

Agencies are aware of the risk of capture and, due to concerns about their reputation as independent regulators, try to limit bias in outputs by including a diverse set of interests in their ACs (Arras and Braun Citation2017; Beyers and Arras Citation2019). This awareness might be further fuelled by the fact that the staff of European agencies is rather homogenous (see Perez-Duran, 2020; Pérez-Durán and Bravo-Laguna Citation2019), thus stressing the need for including a diverse set of interests in their advisory councils. Indeed, agencies are aware of their reputation as credible regulators and (attempt to) highlight their intentions and characteristics, such as integrity or expertise, to different audiences (Busuioc and Rimkutė Citation2020; Carpenter Citation2010). This makes agencies not just experts in specific regulatory fields, but rather (tentative) political entrepreneurs (Busuioc and Rimkute 2020; Wood, Citation2018).

The ACs advise the respective agency on binding regulations, guidelines and recommendations on a regular basis, some even advise an agency to control member states’ efforts to implement EU regulation. For example, the ACs of the ESAs can request the agency to investigate an alleged breach or non-application of EU law. While the councils can only advise and thus have no decision-making power themselves, agencies must report how the advice was implemented, and if not, why it was not implemented. In other words, the agencies must listen to the ACs and take into account their advice, which grants the ACs considerable power in EU regulatory governance.

As agencies themselves have the discretion to select stakeholders, they can use ACs to balance interests and, in doing so, prevent excessive dependence on one type of stakeholder (Beyers and Arras Citation2019). Arras and Braun (Citation2017) find that agencies indeed use ACs to enhance their reputation by balancing interests, indicating an awareness of the risks associated with biased representation. More specifically, agency officials interviewed by Arras and Braun (Citation2017, 12) argued that ACs indeed offer a more balanced opinion on issues compared to the input they received through open consultations. Because biased access may result in biased output, most studies on consultative bodies in the EU have focused on the issue of access. Studying both open and closed consultation instruments, Beyers and Arras (Citation2019) find that although regulated business groups dominate closed consultation instruments in absolute numbers, compared to their relative participation in open consultations, non-business interests, such as NGOs and trade unions, have a higher chance of access to ACs. Authors studying the expert bodies of the European Commission find a strong bias towards business (Chalmers Citation2013; Gornitzka and Sverdrup Citation2011, Citation2015; Rasmussen and Gross Citation2015; Vikberg Citation2020).Footnote2 Overall, assets in terms of expertise and (financial) resources result in more access for business interests compared to non-business interests.

Although these studies have extensively increased our understanding of access to consultative bodies, they merely tell one part of the story. Vivien Schmidt wrote that ‘[t]he normative criteria for democratic legitimacy, in sum, consist of institutional and constructive throughput processes as well as of input participation and output policy’ (Schmidt Citation2013). Indeed, bias is a multidimensional concept and not restricted to access to and output of the ACs. It also concerns how ACs function in practice. While the composition may be diverse and balanced, the way stakeholders interact with each other may still bias a particular interest. As input, throughput and output are interlinked, literature on consultative bodies often assumes that bias (or balance) on one dimension indeed leads to bias (or balance) on another dimension: when access is biased towards business interests, it is likely that the councils’ functioning will largely be dominated by business, which probably results in policies catering business interests. However, other scenario’s may also be true: access to ACs can be balanced but the discussions in the councils may still be dominated by business interests. This paper challenges the idea that diversified membership in ACs will automatically legitimise regulatory policymaking by agencies. To go beyond the current understanding of access (input), we propose to focus on the functioning (throughput) of ACs.

Going beyond access: bias in throughputs

Throughputs refer to the phase between the political input and the policy output (Schmidt Citation2013) and focus on policy-making processes and interactions of all actors engaged in governance, in our case the internal functioning of ACs. This approach is conceptually rooted in Vivien Schmidt’s notion of discursive institutionalism. In broad terms, discursive institutionalism argues that institutions are both given and contingent. Given because institutions are the context in which individuals interact with one another; and contingent because institutions are – at the same time – constructs shaped, transformed and created by individuals (Schmidt Citation2008). Therefore, institutions are ‘internal to the actors, serving both as structures that constrain actors and as constructs created and changed by those actors’ (Schmidt Citation2008, 314). In the case of ACs, the councils’ design constrains but also enables how its members can interact with one another – constraining due to working procedures and informal rules, but enabling because of providing an institutional venue for discussion as well as providing access to key policymakers (see Busuioc and Jevnaker Citation2022). In turn, members’ interaction shapes how the councils function and whether they can deliver more balanced advice, and thus potentially legitimise regulatory policies. We therefore argue that the nature of interest representation is largely shaped by how the ACs’ members make sense of the councils, and how they interact with one another. In the following paragraphs, we draft a framework to assess whether the functioning of ACs is biased. More specifically, we contend that bias in the ACs’ functioning can be determined based on the interaction between council members in combination with the capability of these members.

First, it matters how members of a council interact with other stakeholders. In this regard, we distinguish two ideal types of interaction modes between actors in political settings: bargaining and arguing (Beyers Citation2008; Elster Citation1986; Holzinger Citation2004). Bargaining reflects communication between actors based on resources to be exchanged in order to gain a particular benefit, such as a favourable policy outcome (Beyers Citation2008). It is characterized by a ‘logic of the market’ and primarily directed at exchanging information about (policy) preferences, making promises and threats (Elster Citation1986). Bargaining also includes exchanges of policy positions and technical information, such as details about market technicalities, internal procedures, industry data and effects of policy (Beyers Citation2008). When actors bargain, they mainly focus on what benefits or costs a certain policy outcome has for their own interest. Arguing, on the contrary, reflects communication between actors based on ideas, the nature of these ideas and arguments (Beyers Citation2008). When arguing, actors use arguments to persuade and convince others to adjust their (normative) beliefs and preferences (Risse Citation2000), following a ‘logic of the forum’ (Elster Citation1986). It is less about costs and benefits, but more about ideational outcomes (such as factual beliefs and preferences about what a policy should look like). The goal of arguing is not to attain one's fixed preferences, but to seek a reasoned consensus. Furthermore, actors’ interests, preferences, and perceptions of the situation are not fixed, but subject to discursive challenges (Risse Citation2000).

As Holzinger (Citation2004) and Beyers (Citation2008) already noted, bargaining and arguing are difficult to separate, both theoretically and empirically. Political conflicts are multifaceted, and actors can strategically use and combine either mode to their own advantage (Holzinger Citation2004). This means that in almost all conflicts between political actors both modes of interaction will occur simultaneously. Also empirically the modes are hard to distinguish from one another. They usually appear together: arguing can complement bargaining and vice versa. Also, both modes of interaction might lead to consensus (e.g. consensus might emerge from bargaining too, provided that actors share preferences). Following these theoretical and empirical limitations, it is not our goal to see how and when stakeholders operate in one of these two interaction modes. Instead, we use these two general modes of interaction to determine how members perceive their own and others’ behaviour in the ACs.

Interaction by itself is not enough to establish whether the functioning of ACs is biased. For example, an advisory council might be balanced when a diverse set of stakeholders is equally able to bargain for policy outcomes. Alternatively, a council might still be biased if only a few powerful members reach a reasoned consensus by arguing. Hence, we argue that one also needs to assess the capabilities of stakeholders to contribute to the ACs. Beyers (Citation2008) stresses the importance of stakeholders’ capabilities to control and exchange resources to political actors. Indeed, as discussed, (some) stakeholders possess expert knowledge on markets and regulation which policymakers value. Not only can these informational resources be exchanged for influence in advisory councils (Bouwen Citation2002), but they might also be simply necessary to be able to advise on highly technical regulatory proposals. Besides these informational resources, also stakeholders’ capabilities in terms of organizational resources are crucial to consider. As the ACs must advise agencies on highly technical policy issues, stakeholders are required to prepare for meetings. This preparation might depend on organizational resources, such as staff and budget, thus shaping the capabilities of stakeholders to participate in the meetings. Moreover, policymakers also ascribe more legitimacy to stakeholders who possess valuable resources, such as economic power, policy expertise or political support (Fraussen, Beyers, and Donas Citation2015), thus further enhancing the position of particular stakeholders in the ACs.

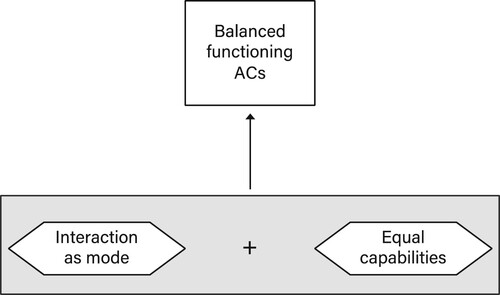

Thus, capabilities in tandem with interaction modes can help to explain unequal opportunities and bias (Beyers Citation2008, 1198). Put differently, we argue that interaction between members and some form of equality of members’ capabilities (i.e. informational and organizational resources) both are necessary conditions. Yet, both must be true and are thus sufficient for a balanced functioning of the ACs. Indeed, the functioning of ACs is balanced when members are equally able to contribute to meetings where arguing is the main interaction mode. In this situation, ACs seek a reasoned consensus by arguing among a wide range of capable members. Oppositely, ACs are biased venues when a select number of resourceful stakeholders bargain for policies that serve their own interest. In this situation, ACs serve as a market where stakeholders exchange information with decision-makers in return for favourable policies. In , we present a conceptual model to understand what drives balanced functioning of ACs.

Observing bias in throughputs

To qualitatively assess biased functioning in ACs, we present five factors that help assessing the working of the ACs and functions as a blueprint on our empirical exploration (see ).

Table 1. Operationalization of interaction and capabilities.

First, we argue that it matters greatly how council members perceive the role of the ACs. On the one hand, members might perceive the councils as venues that ensure open dialogue with a common goal, namely drafting advice based on a reasoned consensus. Alternatively, members may perceive the councils primarily as a venue to bargain for their own interests, hence considering ACs as ‘markets’ where (informational) resources can be exchanged for influence. In this case, the ACs’ raison d'être is to assist resource-exchanges between stakeholders and policymakers.

The second indicator is the members’ perception of their own and their fellow members’ role. First and foremost, members can perceive themselves as representatives of their own organization or constituency. As this does not tell us much about bias or balance per se, we turn to the distinction between arguing and bargaining: how do members act upon their role as representatives of their organization? When arguing is the main interaction mode, we expect members to represent their organizations’ opinion, but also to be able and willing to adjust their interests and beliefs based on arguments raised during the discussions. In other words, interests are not fixed, but subject to reasoning. On the contrary, members can also see their role as representatives in a strict sense, perceiving themselves as promoters of their organization’s interests. In this case, members have fixed preferences and are not willing to adjust their initial interests to serve a common goal.

Thirdly, we expect that the interaction modes affect the discussions. Arguing implies consensual discussions. Members exchange positions and attempt to reconcile contradicting policy preferences. On the contrary, bargaining implies contradiction: members explicitly express their preferences in terms of their organization’s interests and convey political information (e.g. on the constituency they represent). As the meetings consist of members with different opinions, the goal of the meetings is to ‘take a picture’ of the various viewpoints, rather than to find a consensus among stakeholders.

The second axis focuses on two dimensions of individual members’ capabilities in terms of informational and organizational resources. First, whether stakeholders have the necessary expertise and technical knowledge to adequately provide their opinion, matters greatly when assessing bias in ACs. On the one hand, members, be they business or consumer representatives, should have sufficient expertise to operate in the councils as the agency prefers to appoint knowledgeable individuals. Also, as the members are representatives from organizations with a pre-established interest in regulation, they will have expertise to form an opinion on this matter. On the other hand, however, it is likely that there is profound variation among members. In a wide range of regulatory issues business representatives have a considerable advantage over other council members, due to their direct knowledge about the functioning of regulation in their business. Even if business representatives lack the individual expertise to form an opinion on a certain issue, they have the (financial) resources to acquire that expertise (e.g. by establishing an internal work team, hiring external experts, or conducting own research). Less resourceful members, such as national consumer groups or NGOs, do not have this possibility and are likely to depend mostly on their personal capacities, ending up with fewer capabilities to voice preferences or well-founded opinions.

Finally, as the contribution of individual members can still differ even when they have equally sufficient expertise, there might be variation in members’ perception of their own contribution to the meetings due to limited organizational resources. If all members feel that they are equally able to raise issues, to participate and have an equal share in the decision-making, bias might be limited. On the contrary, if – due to asymmetries in organizational resources – agenda-setting, discussions and decision-making are dominated by members representing business interests, there is risk for biased throughput.

Qualitative interviews to investigate bias

To illustrate the applicability of the theoretical framework in empirical research, we conducted interviews with members of the ACs of two European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs): the European Banking Authority (EBA) and the European Insurances and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA). In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, these agencies were delegated the sole power to draft regulatory technical standards: legally binding regulation that is directly applicable in all member states. In addition, the ESAs have considerable powers during emergency situations, and can operate quite independently from the Commission (Busuioc Citation2013). Hence, the ESAs have a significant impact on the content of financial regulation and on those affected by these regulations. The ACs of the ESAs are also considerably powerful, as they have been granted broad mandates with respect to providing input on a broad range of aspects pertaining to the agency’s functioning and core tasks, including in relation to key functions such as rulemaking (Busuioc and Jevnaker 2020).

Next to their powerful position, the ACs of the ESAs are interesting due to legal requirements concerning the composition of the ACs. As regulators, ESAs not only seek technical expertise, but also legitimation (Busuioc and Rimkute 2020). A diversified membership of their ACs is particularly pressing as these ESAs have a known bias towards regulated interests in their interactions with stakeholders, for example in their public consultations (Chalmers Citation2015; Pagliari and Young Citation2015; Quaglia Citation2008). Hence, for this reason, the legislator has spelled out detailed composition requirements (Busuioc and Jevnaker 2020). The ESAs have three ACs in total: The Banking Stakeholder Group (BSG), the Insurances and Reinsurances Stakeholder Group (IRSG), and the Occupational Pensions Stakeholder Group (OPSG). Each AC has 30 members and is legally bound to reserve five seats for independent academics. The other members are selected based on balanced proportions of financial market participants, employees’ representatives as well as consumers, users of financial services and representatives of SMEs. In short, ESAs are among the few agencies that are obliged by law to balance the composition of their advisory councils and include different types of stakeholders (Busuioc and Jevnaker Citation2022). Yet, at the same time, the highly technical nature of financial regulation makes that there are profound information asymmetries between stakeholders. The mandated balance in combination with asymmetries makes the ESAs a fitting venue to study whether stakeholders are arguing or bargaining and to what extent each of them is capable to contribute to the ACs.

Based on four semi-structured pilot interviews with members, we developed a comprehensive interview guide containing questions on members’ perception of the council’s role and their own, the used procedures during meetings, characterization of discussions, members’ expertise, and members’ ability to contribute to discussions. In total, we conducted thirteen in-depth interviews with members of the ACs (see Appendix A for an overview). All members had a seat in the 2018–2020 mandate period, and interviews took place at the end of their mandate. This has three main advantages. First, arguing might have a temporal dimension as stakeholders might need time to get socialized and acquainted with other members and their viewpoints to make consensus possible (also see Checkel Citation2005). Hence, it is more likely that processes of arguing and consensus-seeking take place at the end than at the start of the mandate. Second, at the end of their mandate, members have a better and more thorough account of how the councils function. Third, and related, as some members were not planning to serve a second term (or already served two terms) they could reflect more openly on their role and on the ACs functioning without risking scrutiny.

If members served more than one term or served in more than one council, we always made explicit which one was being discussed. The interviews were conducted over a period of two months (February and March 2020), lasted an hour on average, and took place via Skype or face-to-face. Three respondents were members of BSG, four of OPSG and six of IRSG. Four interviews were conducted with consumer representatives, two with members representing employees, employers and/or users of financial services, five with academics and two with business representatives.

While not a truly representative sample, these interviews serve to explore the way the ACs function, and especially whether non-business stakeholders are able to meaningfully contribute to the ACs. As such, this empirical endeavour in understanding these councils via the perceptions of its members provides an illustration of how bias can be investigated qualitatively.

Recordings of the interviews have been transcribed by two assistants and subsequently coded by the authors. Following the concepts presented in , the interviews were conducted following a guide consisting of topics such as ‘role perception’, ‘venue perception’, ‘conflict’, ‘lobbying behaviour’, etc. Each topic had a specific list of questions, which can be found in Appendix C. We also asked members what they would change, and whether they thought the ACs are an effective instrument to create balanced advice for the agencies.

Interaction: willingness to compromise, but interests prevail

First, members’ perception of the ACs role is rather uniform: most members (12/13) report that the councils’ main task is to bring different stakeholders together with the goal to advise the agency. However, members have different perceptions on how this advice should come about. Some (4/13) report that the advisory reports should be balanced and result from a compromise between the various members. Others (7/13), however, see the councils as societal ‘antennas’: the agencies ask the councils to give input on specific issues and the members are expected to share their views. Rather than finding a compromise, the latter argue that the advisory reports should reflect a wide array of views and opinions. In other words, although the goal of the ACs is well internalized by members, they tend to disagree on whether the AC should act as a forum or as a market.

Second, turning to role perception, council members see themselves first and foremost as representatives, either of their specific organization or of a constituency, such as savers, national or European consumers, employees or employers. The interviews show that members cannot fully decouple their professional role as representative of their own organization from their role as council members. Yet, as one respondent reported: ‘The members of Stakeholder Groups are considered to represent only themselves and not the institutions they [work for]. It was a very ideal approach. If not, naïve’ (INT1402201). Another member (INT130320) mentioned that they were aware they should participate in the councils in their own capacity, but that they realized that their representative role always took over during the meetings. Only a minority (3/13) report that they mainly are member in their personal capacity. These members perceive themselves as individual experts endowed with specific expertise resulting from their professional background, which helps them to actively seek a compromise.

Although members perceive themselves as representatives, they indicate that they try to seek a compromise between different views and opinions. Members report that they value the wide array of opinions and views presented during the discussions. They repeatedly mentioned vivid and lively discussions among members. Respondents (5/13) also stated that the goal of the discussions is to share insights, opinions and views rather than to make statements about own preferences. In some cases, respondents explicitly mentioned that they changed their opinions due to the discussion. This shows that members’ preferences are not fixed, but subject to different views and opinions expressed in an open dialogue. In contrast with members representing a constituency or organization, academic members perceive themselves as independent experts who provide neutral and objective information (5/5). They feed the discussions with independent research, sometimes also contradict information presented by the other members, thus helping to ensure a balance in the council’s discussions and to find a basis for compromise. In summary, the role perception of members in ACs highlights that members see themselves as representatives, and that their preferences are subject to change. Through open dialogue, argumentative processes and discussion members try to seek compromise in the meetings.

Third, turning to the discussions within the ACs, respondents are quite univocal. Most members (11/13) report that the discussions are primarily focused on reaching a consensus or compromise between the members’ different views. One member described it as follows:

We are not taking part in the debate to make a statement (…) Normally, we are really trying to reach a common decision or to reach a global advice, a common opinion, a shared point of view. It’s very rich, I think. (INT030320).

Although the possibility for members to opt for a minority position prevents deadlocks and ensures that all can express their opinion, it also limits the necessity for true consensus. Instead of finding consensus, ACs often have to resort to ‘taking a picture’ of the various (contradicting) viewpoints, rather than being able to reconcile them. This further highlights the tension between bargaining (i.e. presenting policymakers one’s own interests) and arguing (i.e. deliberating policy preferences and finding consensus) as suggested by our hypotheses.

These findings show that members mainly interact by arguing. Members are willing to adjust their initial preferences with the goal to find consensus, as other scholarship has identified in similar settings (e.g. Tsingou Citation2015). However, this does not mean that they do not seek to influence the output of the AC. As members primarily perceive themselves as representatives of their own organization, they still try to defend their organizations’ interests, thus making it difficult to find a consensus. Moreover, due to the possibility to adopt minority positions, a true consensus is not necessary, allowing members to advocate their own interests to the agency.

Capability: asymmetries in resources

In terms of informational resources, members explicitly described the discussions as technical and/or based on expertise (10/13). They report that many issues deal with specific regulations rather than with broader topics, such as long-term strategy plans of the ESAs or with the general role of banking, pensions and insurances in modern societies (INT1702201). Although members report a background in economics, law or consumer protection, they sometimes lack the necessary expertise to participate in the discussions. There seems to be an agreement that all members have the appropriate credentials as experts in the field of financial regulation, but that the discussions often require ‘insider-information’ that is only available to the regulated business and the agency itself. One member argued that ‘Nowadays, the more technical the issues get, the more the discussion is one-sidedly held between [the agency] and business representatives’ (INT200220). Indeed, members report that there is a level of amateurism at the side of the consumers (INT200220; INT1702202), or that consumer representatives resort to personal opinions with anti-business sentiment rather than factual information (INT130320).

The asymmetry in expertise between members also results from the selection procedure. One member described the procedure as a sudoku puzzle: not only has the agency to match expertise and affiliation (i.e. business, employees, consumers, academics), it must also seek a balance in nationality and gender. These criteria sometimes result in trade-offs between competence and nationality or competence and gender (INT100220). Moreover, all members report variation in the contribution to the councils due to the differences in expertise. Some argue that this depends on the topic: most members can contribute to discussions on broader issues, but not on specific technical discussions.

Turning to asymmetries in organizational resources between members, the interviewees indicate profound differences between members’ contribution to the meetings. Some members seldomly or never express their opinion during their two-year mandate (INT200220). Variation in participation also occurs in setting the agenda and drafting the advisory reports and recommendations. ACs appoint a working group that discusses and drafts a first version of the advisory report that will later be discussed in a plenary meeting. Members themselves can choose whether to participate in a working group. However, participation requires a considerable amount of time and effort, and sometimes also requires access to legal teams. As members do not receive financial compensation for this, especially non-business groups have to be selective. Business representatives often take the lead in drafting the advisory reports of the ACs as they have access to legal teams or assistants, while the other members have to ‘choose their battles’. As a result, business representatives are the most active, while the others around the table are more reactive (INT130320; INT120320; INT200220).

Similarly, members (9/13) mention insufficient financial resources as a hurdle to contribute to the meetings. Although non-business members receive a compensation for accommodation and travel costs for the plenary meetings, they are not compensated for informal meetings, such as roundtables, working groups and presentations. As a result, they sometimes have the idea that they miss out on relevant discussions. Moreover, non-business members repeatedly mentioned that they lack the financial resources to conduct their own research or to collect their own data and therefore must resort to more ideological, and therefore less powerful arguments (INT130320; INT140220).

Likewise, members (8/13) identify considerable variation in terms of staff and organizational support. As mentioned above, preparing the meetings, contributing to working groups and getting acquainted with the issues at hand takes time and effort. Academic and consumer representatives often lack support from their organizations while business representatives can rely on legal teams to prepare meetings and to help draft advisory reports. As a result, members without a back office need to ‘work harder to keep up and need to be more selective in the issues they want to contribute to’ (INT100220).

These findings highlight that some members are simply more capable to contribute to the meetings than others. Indeed, whether a stakeholder has the right inside information and expertise or whether it has organizational resources to prepare for the meetings affects the extent to which that member can contribute to the advisory report that is submitted to the agency. Our interviews indicate that especially non-business actors struggle to ‘keep up’ with business members. Not only do these findings further demonstrate the importance of resources to explain stakeholders’ influence (Bouwen Citation2002; Coglianese, Zeckhauser, and Parson Citation2004), they also point into the direction of biased functioning.

Understanding bias better: avenues for qualitative research

Looking back at the theoretical framework, our findings largely point towards arguing as the main interaction mode. Members do not merely bargain for policies that serve their own interest but actively seek consensus by sharing views and opinions. They are aware that they are supposed to reach consensus and might have to adjust their preferences to do so. Members are motivated to deliberate and are willing to put the common good above their own private interests. However, despite this initial motivation, consensus is often hard to establish due to the delicate balancing act of defending own interests vs. finding consensus. ACs therefore rather ‘take a picture’ of the various policy preferences at the table instead of presenting a consensus. In addition, our findings show that there is a profound asymmetry in the level of expertise between members. Consumer representatives do not only lack sufficient information and expertise to contribute to the meetings, but they also experience structural disadvantages in terms of financial and organizational resources, preventing them from effectively contributing to the functioning of the ACs.

These exploratory findings thus highlight the further need for more refined ways for studying bias. Rather than merely looking at access, scholars should also consider the functioning of the ACs (also see Busuioc and Jevnaker Citation2022), potentially in terms of interaction modes and capabilities. Although this research note is based on a limited number of interviews, it raises questions about whether ACs can actually contribute to more balanced policymaking by EU agencies. As one respondent mentioned: ‘There is this danger that a so-called independent Stakeholder Group, that is clearly dominated by the industry, can legitimise certain policies’ (INT200220). Domination by business interests cannot be solved by merely providing access for non-business actors. Instead, respondents argue that agencies should make efforts to decrease the structural disadvantages that some members face in order to increase the likelihood of balanced opinions, and ultimately ensure that the agencies will be legitimate policymakers.

To be able to study bias in a more refined manner, we thus first propose scholarship to go beyond studying solely access and start digging into the functioning of these venues. This can take form as a qualitative study using similar concepts as proposed in this research note such as members’ perceptions on the venue, their own role, and their contributions. This research note did so on a relatively small scale for two ACs of very specific EU agencies: the ESAs. These councils were particularly interesting to test the theoretical framework presented above, due to their mandated balance and composition as well as asymmetries between members. However, as financial regulation is highly technical it also is likely to induce business dominance in the ACs and limit non-business groups capabilities, as also demonstrated in the interviews. What remains unknown is whether the ACs of other EU agencies also function similarly. In particular, it would be highly interesting to explore ACs in policy fields in which the asymmetries between members’ resources are less pronounced. One could think of policy areas such as climate change, forestry, or environment, where technical information can be complemented with information about effects on citizens or the climate. In our interviews, members indicated instances in which specific topics (such as pensions) allowed for more equal discussions among members, as different types of information (both expertise and citizen information) were necessary (INT100220; INT1702201). This might lead to the hypothesis that topic or policy area matters. Comparing policy fields with varying levels of technicality would thus allow one to see whether the ACs in these are more balanced when policy areas are less technically complex. Also, it would be highly interesting to study ACs that are not mandated to have a balanced composition. One might hypothesize that bias towards business is more pronounced when an agency is less prescriptive regarding the composition of its ACs. We thus welcome studies that (comparatively) investigate ACs of various agencies to investigate how and to what extent interaction and capabilities among stakeholders varies. We also suggest also to include variation in agencies with respect to regulatory powers to test the hypothesis that ACs in less powerful agencies suffer less from a bargaining mode.

Furthermore, to truly understand how these councils function, observational research is crucial, especially to empirically gauge the modes of interaction (also see Holzinger Citation2004). Unfortunately, we did not get access to the ACs to observe the meetings, but this would be highly valuable to propose in future research. Not only can dynamics of interaction modes be observed, also capabilities and expertise are visible in these meetings. Triangulating observational data with the eventual outputs of the ACs and accompanied interviews, we can truly understand how members interacted, how their interests are translated into the report, what interests are likely to be silenced or diminished, and who is most successful in representing their interests. These questions are crucial in understanding bias more deeply.

Besides solely studying the venues qualitatively, we also think triangulation of methods is crucial. It would be highly interesting to combine qualitative and quantitative methods to investigate which members express most ‘minority opinions’ in the final reports, across a wide range of agencies. This way we can see which stakeholders are the odd ones out in the ACs. We might, for example, expect that groups such as consumer organizations or trade unions more often take a minority position in the ACs, further indicating bias. Second, including data on members’ organization features (type of interest group, resources, …) and member’s personal characteristics (experience, previous affiliations, …) would enable to identify the contexts that foster or prevent bias in EU agencies.

This research note functions as a first step to understand bias better. Extending scholarship from mere quantitatively assessing the diversity of AC membership (but see Busuioc and Jevnaker Citation2022), we stress the importance of qualitative methods to understand the internal functioning of the councils. The qualitative approaches as described above highlight avenues that future research could take to understand the complex and multifaceted concept of bias in a more meaningful manner.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For a discussion, please see Busuioc (Citation2013).

2 European Commission expert groups are formally defined as ‘consultative entities set up by the Commission or its services, comprising at least six public and/or private sector members, which are foreseen to meet more than once’ (European Commission Citation2010, 3). While expert group members very often include officials from national governments as well as individual experts, they also frequently include powerful business interests, trade unions, professional associations and large NGOs representing their own interests at the EU-level. Chalmers (Citation2013) demonstrates that the stakeholder-members in these groups are predominantly business interests with high resources and an insider status.

References

- Arras, S., and C. Braun. 2017. “Stakeholders Wanted! Why and How European Union Agencies Involve Non-State Stakeholders.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (9): 1257–1275.

- Ayres, I., and J. Braithwaite. 1992. Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Baxter, L. G. 2011. “Capture in Financial Regulation: Can We Channel It Toward the Common Good.” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 21: 175.

- Beyers, J. 2008. “Policy Issues, Organisational Format and the Political Strategies of Interest Organisations.” West European Politics 31 (6): 1188–1211. doi:10.1080/01402380802372654.

- Beyers, J., and S. Arras. 2019. “Who Feeds Information to Regulators? Stakeholder Diversity in European Union Regulatory Agency Consultations.” Journal of Public Policy 40 (4): 573–598.

- Beyers, J., C. Braun, D. Marshall, and I. De Bruycker. 2014. “Let’s Talk! On the Practice and Method of Interviewing Policy Experts.” Interest Groups & Advocacy 3 (2): 174–187.

- Binderkrantz, A. S. 2012. “Interest Groups in the Media: Bias and Diversity Over Time.” European Journal of Political Research 51 (1): 117–139.

- Borrás, S., C. Koutalakis, and F. Wendler. 2007. “European Agencies and Input Legitimacy: EFSA, EMeA and EPO in the Post-Delegation Phase.” Journal of European Integration 29 (5): 583–600. doi:10.1080/07036330701694899.

- Bouwen, P. 2002. “Corporate Lobbying in the European Union: The Logic of Access.” Journal of European Public Policy 9 (3): 365–390.

- Braun, C. 2012. “The Captive or the Broker? Explaining Public Agency–Interest Group Interactions.” Governance 25 (2): 291–314.

- Buess, M. 2015. “European Union Agencies and Their Management Boards: An Assessment of Accountability and Demoi-Cratic Legitimacy.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (1): 94–111.

- Busuioc, M. 2013. “Rule-Making by the European Financial Supervisory Authorities: Walking a Tight Rope.” European Law Journal 19 (1): 111–125.

- Busuioc, M., and T. Jevnaker. 2022. “EU Agencies’ Stakeholder Bodies: Vehicles of Enhanced Control, Legitimacy or Bias?” Journal of European Public Policy 29 (2): 155–175.

- Busuioc, M., and M. Lodge. 2016. “The Reputational Basis of Public Accountability.” Governance 29 (2): 247–263.

- Busuioc, M., and D. Rimkutė. 2020. “Meeting Expectations in the EU Regulatory State? Regulatory Communications Amid Conflicting Institutional Demands.” Journal of European Public Policy 27 (4): 547–568.

- Carpenter, D. P. 2010. Reputation and Power: Organizational Image and Pharmaceutical Regulation at the FDA. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Carpenter, D. P., and D. A. Moss. 2013. Preventing Regulatory Capture: Special Interest Influence and How to Limit It. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Chalmers, A. W. 2013. “Trading Information for Access: Informational Lobbying Strategies and Interest Group Access to the European Union.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (1): 39–58.

- Chalmers, A. W. 2015. “Financial Industry Mobilisation and Securities Markets Regulation in Europe.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (3): 482–501.

- Checkel, J. T. 2005. “International Institutions and Socialization in Europe: Introduction and Framework.” International Organization 59 (4): 801–826.

- Coglianese, C., R. Zeckhauser, and E. Parson. 2004. “Seeking Truth for Power: Informational Strategy and Regulatory Policymaking.” Minnesota Law Review 89: 277.

- Elster, J. 1986. “The Market and the Forum: Three Varieties of Democratic Theory.” In Foundations of Social Choice Theory, edited by J. Elster, and A. Hylland, 103–132. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- European Commission. 2010. Communication from the President to the Commission: Framework for the Commission Expert Groups: Horizontal Rules and Public Register, C(2010) 7649 final, 10 November 2010, Brussels.

- Fraussen, B., J. Beyers, and T. Donas. 2015. “The Expanding Core and Varying Degrees of Insiderness: Institutionalised Interest Group Access to Advisory Councils.” Political Studies 63 (3): 569–588.

- Furlong, S. R., and C. M. Kerwin. 2004. “Interest Group Participation in Rule Making: A Decade of Change.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 15 (3): 353–370. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui022.

- Gornitzka, Å, and U. Sverdrup. 2011. “Access of Experts: Information and EU Decision-Making.” West European Politics 34 (1): 48–70.

- Gornitzka, Å, and U. Sverdrup. 2015. “Societal Inclusion in Expert Venues: Participation of Interest Groups and Business in the European Commission Expert Groups.” Politics and Governance 3 (1): 151–165.

- Grabosky, P. 2013. “Beyond Responsive Regulation: The Expanding Role of non-State Actors in the Regulatory Process.” Regulation & Governance 7 (1): 114–123.

- Holzinger, K. 2004. “Bargaining Through Arguing: An Empirical Analysis Based on Speech act Theory.” Political Communication 21 (2): 195–222.

- Klüver, H. 2012. “Biasing Politics? Interest Group Participation in EU Policy-Making.” West European Politics 35 (5): 1114–1133. doi:10.1080/01402382.2012.706413.

- Lowery, D., F. R. Baumgartner, J. Berkhout, J. M. Berry, D. Halpin, M. Hojnacki, H. Klüver, B. Kohler-Koch, J. Richardson, and K. L. Schlozman. 2015. “Images of an Unbiased Interest System.” Journal of European Public Policy 22 (8): 1212–1231.

- Pagliari, S., and K. L. Young. 2015. “The Interest Ecology of Financial Regulation: Interest Group Plurality in the Design of Financial Regulatory Policies.” Socio-Economic Review 14 (2): 309–337.

- Pérez-Durán, I. 2019. “Political and Stakeholder’s Ties in European Union Agencies.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (1): 1–22.

- Pérez-Durán, I., and C. Bravo-Laguna. 2019. “Representative Bureaucracy in European Union Agencies.” Journal of European Integration 41 (8): 971–992.

- Quaglia, L. 2008. “Financial Sector Committee Governance in the European Union.” European Integration 30 (4): 563–578.

- Rasmussen, A., and V. Gross. 2015. “Biased Access? Exploring Selection to Advisory Committees.” European Political Science Review 7 (3): 343–372.

- Risse, T. 2000. ““Let’s Argue!”: Communicative Action in World Politics.” International Organization 54 (1): 1–39.

- Schmidt, V. A. 2008. “Discursive Institutionalism: The Explanatory Power of Ideas and Discourse.” Annual Review of Political Science 11 (1): 303–326. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342.

- Schmidt, V. A. 2013. “Democracy and Legitimacy in the European Union Revisited: Input, Output and ‘Throughput’.” Political Studies 61 (1): 2–22.

- Stigler, G. J. 1971. “The Theory of Economic Regulation.” The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2 (1): 3–21.

- Tsingou, E. 2010. “Regulatory Reactions to the Global Credit Crisis: Analyzing a Policy Community Under Stress.” In Global Finance in Crisis, edited by E. Helleiner, S. Pagliari, and H. Zimmermann, 35–50. London: Routledge.

- Tsingou, E. 2015. “Club Governance and the Making of Global Financial Rules.” Review of International Political Economy 22 (2): 225–256.

- Vikberg, C. 2020. “Explaining Interest Group Access to the European Commission’s Expert Groups.” European Union Politics 21 (2): 312–332.

- Wood, M. 2018. “Mapping EU Agencies as Political Entrepreneurs.” European Journal of Political Research 57 (2): 404–426.

Appendices

Appendix A: Overview of respondents

Appendix B: Social desirability

Using expert interviews requires to address the possibility respondents giving socially desirable responses to sensitive questions. Indeed, when asking members about their level of expertise or their contribution to the meetings, they might over- or under-estimate their role in the bodies (Beyers et al. Citation2014). We limited this by asking more sensitive questions towards the end of the interview as to use the established trust relationship between interviewer and interviewee. Also, when discussing sensitive topics, we asked multiple questions that tease out a fair estimation of the interviewee. For example, when asking about their expertise, we not only asked whether they felt they had sufficient expertise, but also whether they thought other members had more expertise, and whether they would reckon it useful and necessary to have equal expertise. Besides, most members were surprisingly honest and direct about their level of expertise or contribution to the meetings. Some respondents even admitted that their role is rather limited in the ACs (INT170220; 1402201), and that they do not wish to serve a second mandate (INT170220), indicating that we sufficiently created a safe and trusting environment during the interviews, thus limiting socially desirable responses.

Appendix C: Interview guide

0. Procedural questions

0.1 Recordings?

0.2 Participant Information Sheet and Informed Consent Form

0.3 Introduction own research

1. Background stakeholder representative

1.1 What is your role at your organization?

1.2 How long are you active as a member of the Stakeholder Group?

1.3 How were you selected to be a member of the Stakeholder Group? Do you know why you were selected?

Asked by agency

Asked by other member

Asked by chairman of Stakeholder Group

1.4 In what other ways is your organization involved in the work of the agency? Does your organization participate in public consultations? Do you or one of your colleagues have informal contacts with agency officials?

How often do you have informal contacts?

What are the differences between involvement via public consultations and via Stakeholder Groups?

1.5 Optional: If you are member of multiple Stakeholder Groups, would you say that these Stakeholder Groups are comparable to one another? Are there differences between the Groups?

2. Functioning of Stakeholder Groups

2.1 What do you think is the primary task or function of the Stakeholder Group in the agency? Could you give an example of this primary task?

2.2 What other tasks of the Stakeholder Group are relevant for the agency?

2.3 Are there different types of meetings? Are there different types of issues on the agenda?

2.4 How would you characterise a typical meeting of the Stakeholder Groups? What are the followed procedures during a meeting? Could you describe what a typical meeting looks like?

Are you meeting other members before or after the meeting?

2.5 How does the Stakeholder Group decide what topics to discuss? Do you follow the agenda and working programmes of the agency? Is it possible to initiate reports or opinions as a member?

Are some members more prone to initiate reports than others?

2.6 Are you as a member able to (co-)decide on the agenda of the Stakeholder Group? Could you give an example where you introduced a topic on the agenda? Are other members able to (co-)determine the agenda?

2.7 What are some of the outputs of the Stakeholder Group?

2.8 I noticed in the minutes of the Stakeholder Groups that there are agency officials attending the meetings. What is their role during the meetings?

Does their presence affect the tone/content of the discussions?

3. Discussions in the Stakeholder Groups

3.1 How would you characterise the discussions in the Stakeholder Groups? Could you describe a typical discussion of the Stakeholder Groups?

Examples: driven by expertise/driven by interests; a select number of members drive the discussions; which member stake the lead; importance of reputation/expertise/impartiality; conflictual/consensual; differences between junior/senior members.

3.2 Different stakeholders with different interests often have different positions on certain issues which can sometimes lead to conflict. Can you give an example of a conflictual issue on which members had different positions?

3.3 How does the Stakeholder Group deal with interests that conflict each other? Are there ways to hold minority positions into account?

3.4 In general, how easy or how difficult is it for the members to establish a common position on issues discussed within the body? Are difficulties rather exceptional or unexceptional?

3.5 How are decisions made within the Stakeholder Group? Does the agency have a role in these decisions?

3.6 Following from what we have discussed, do you think the Stakeholder Group is a useful instrument for the agency to consult stakeholders? Does the Stakeholder Group function as it should? What could be improved?

4. Your role as a member of a Stakeholder Group

4.1 What do you see as your primary task as a member of the Stakeholder Group? Could you give an example?

4.2 What other role(s) do you have as a member of a Stakeholder Group?

4.3 How does your role differ from other members of the Stakeholder Group?

4.4 How do you use your expertise during the discussions? Could you give an example?

- Technical/Scientific expertise

- Expertise about own organization

- Expertise about your constituency

4.5 How do you compare your level of expertise to that of other members?

- Technical/Scientific expertise

- Expertise about own organization

- Expertise about your constituency

4.6 Would you say that your expertise is sufficient to helpfully contribute to discussions in the Stakeholder Group?

4.7 Are all members able to contribute meaningfully to the discussions of the Stakeholder Group? Which members are able to and which ones are less able to?

4.8 What are the benefits of being a member of a Stakeholder Group? How do those benefits help you or your organization?

Examples: extra venue/channel for policy influence; privileged access to policymakers; exposure of organization at agency; credibility/reputation-building; expanding own network; informed first about plans agency; insight-sharing between members.

5. Contribution to policy outcomes

5.1 Do you think the Stakeholder Groups contribute to regulatory policies of the agencies? In what way?

5.2 Do you think that you as member are able to contribute to regulatory policies of the agencies? In what way?

5.3 Do you think that being a member of a Stakeholder Group enhances your chances for influencing regulatory policies?

5.4 If we consider lobbying as ‘trying to influence policy / regulation’, how exposed are Stakeholders Group to lobbying by its members? Could you give an example of lobbying behaviour?

5.5 Which members try to influence most, or most frequently?

5.6 One of the reasons the agency installed the Stakeholder Groups is to ensure a more balanced opinion on regulatory policies. Do you think the Stakeholder Group is an effective instrument to realize this? Why?

6. Concluding questions

6.1 Is there anything you would like to share regarding the Stakeholder Group that we have not discussed in the interview?

6.2 Would you be willing to share contact details of other members who did not yet participate in this research?