Abstract

Purpose

The primary aim of this study was to assess the predictive validity of cumulative grade point average (GPA) for performance in the International Foundations of Medicine (IFOM) Clinical Science Examination (CSE). A secondary aim was to develop a strategy for identifying students at risk of performing poorly in the IFOM CSE as determined by the National Board of Medical Examiners’ International Standard of Competence.

Methods

Final year medical students from an Australian university medical school took the IFOM CSE as a formative assessment. Measures included overall IFOM CSE score as the dependent variable, cumulative GPA as the predictor, and the factors age, gender, year of enrollment, international or domestic status of student, and language spoken at home as covariates. Multivariable linear regression was used to measure predictor and covariate effects. Optimal thresholds of risk assessment were based on receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Results

Cumulative GPA (nonstandardized regression coefficient [B]: 81.83; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 68.13 to 95.53) and international status (B: −37.40; 95% CI: −57.85 to −16.96) from 427 students were found to be statistically associated with increased IFOM CSE performance. Cumulative GPAs of 5.30 (area under ROC [AROC]: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.72 to 0.82) and 4.90 (AROC: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.66 to 0.78) were identified as being thresholds of significant risk for domestic and international students, respectively.

Conclusion

Using cumulative GPA as a predictor of IFOM CSE performance and accommodating for differences in international status, it is possible to identify students who are at risk of failing to satisfy the National Board of Medical Examiners’ International Standard of Competence.

Introduction

The term “global village” implies commonalities of human behavior across geographic barriers.Citation1 This phenomenon is manifested in medical education in multiple initiatives,Citation2 including telemedicine,Citation3,Citation4 distance learning technologies,Citation5 and the establishment of satellite campuses.Citation6 There is increasing mobility in the medical workforce, with movement of practitioners and students from one country to another, in addition to the emergence of the “global professional” for reasons related to training opportunities,Citation7 labor demands, and initiatives.Citation8,Citation9

Increasing professional mobility has highlighted the need to develop common educational standards to guide quality improvement efforts and to serve as the components of an accreditation framework for practitioners and medical schools globally, and this is reflected in a number of government-sponsored schemes such as the European Union’s Lifelong Learning Program: 2007–2013 and the Bologna Process.Citation10,Citation11 Pivotal to the success of these schemes is the need to benchmark core medical knowledge. A number of groups have developed measures to test whether standards are being met, as well as to facilitate collaboration in the development of standards.Citation12,Citation13

One such measure developed by the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) is the International Foundations of Medicine (IFOM) Clinical Science Examination (CSE). This was first used in 2007 by a consortium of medical schools in Portugal and Italy. It is now used in more than 10 countries and is administered by more than 60 universities.Citation14 In 2015, it was administered to more than 4,400 examinees, a 6-fold increase since its inception.Citation15 Its aims include provision of summative and formative evaluations of students, assisting residency selection, curriculum evaluation, and local or regional certification. Students use the examination to gain familiarity with the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) process and for access to international residency programs. For medical schools, its usefulness is primarily in terms of curriculum evaluation against an international benchmark and, in some instances, as a barrier examination.Citation16,Citation17

Because of the significant investment by both students and medical schools in the study of medicine,Citation18,Citation19 it is important to identify students at risk of performing poorly. The IFOM CSE offers the chance to compare students with an international benchmark. Early identification of students at risk permits better use of resources aimed at improving their chances of success.

Variables showing a positive association with academic performance on medical assessments such as the IFOM CSE have been identified, with admission tests such as the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT), as well as the undergraduate and postgraduate grade point averages (GPAs), being reported regularly.Citation20–Citation24 Demographic variables including age, gender, and language spoken at home have also been reported as being highly predictive.Citation25,Citation26 However, for age and gender, there is lack of consensus in the literature on the directional effect of these variables; a number of studies have reported that older or female students are more likely to underperform, while others have found the converse.Citation27 Medical students who are native speakers of the language in which they are assessed have consistently been seen to achieve higher assessment scores.Citation28

While many studies in the literature have focused on students at risk identified by the performance in the USMLE Step 2-Clinical Knowledge test, the same is not true for the IFOM CSE. The purpose of this study is to address this issue in 2 connected areas. The first is to determine the cognitive and non-cognitive variables that best predict IFOM CSE performance, and the second is to use this result to develop a risk assessment tool to identify students who will perform poorly relative to the NBME’s International Standard of Competence (ISC).Citation29,Citation30

Methods

Subjects and setting

The study design has been described previously.Citation30 Data were collected in November 2012 from a graduating MBBS class at the medical school of The University of Queensland.Citation30 The 4-year MBBS program has 2 phases, each of 2 years, with the latter phase including disciplines of child health, general practice, gynecology, internal medicine, mental health, pediatrics, obstetrics, rural medicine, surgery, as well as the subspecialties in medicine and surgery by means of community placements and hospital-based clinical schools. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from The University of Queensland’s Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee and all of the students provided written consent.

Study variables

In this study, the dependent variable was student performance on the IFOM CSE. Developed by the NBME, the purpose of this examination is to assist medical schools in benchmarking their own students against a global standard, in this case, the minimum passing score for Step 2 of the USMLE (ISC). Specific details of this test have been described elsewhere,Citation15 but briefly, the IFOM CSE consists of 160 multiple-choice questions across 18 domains. Taken in a 4.5 hour testing day, it can be administered electronically or in hard copy. The scores are standardized to a mean of 500, a standard deviation (SD) of 100, and a range from 200 to 800. Unlike the overall IFOM CSE score, domain scores are not standardized to this interval. For these taking the 2012 iteration, the ISC was set at a score of 557.

The independent variable of primary interest in this study was the cumulative grade point average (cGPA), which was obtained by measuring students’ academic performance throughout their MBBS program. For most students, this was a 4-year period, but for some, it was longer due to periods of leave. For each semester course, written and clinical examinations were used to generate a grade on a discrete scale of 1–7, which in turn was averaged to provide a semester GPA on a continuous scale of 1–7. A secondary averaging process was then implemented to produce a cGPA on the same scale as semester GPAs.

Remaining demographic and educational variables that might be potential confounders of the cGPA and IFOM CSE relationship were extracted from admission records. Demographical data included the following: age (<25 years, 25–29 years, and 30+ years); gender; and language spoken at home (English, not English). Educational data included the following: international status (yes, no); MBBS enrollment (pre-2009, 2009, and post-2009); and MBBS entry pathway (graduate, nongraduate). The entry variable refers to the 2 pathways leading to MBBS enrollment at the study university. The second category denotes MBBS students who are provisionally accepted into the program on the proviso that 2 years of an undergraduate degree be completed successfully before entry to medical school. Variation from an MBBS enrollment of 2009 (typical of most students) was due to either failure with a repeat year or transfer from another medical school.

Data analysis

Categorical covariates are presented as counts and proportions, with accompanying summary statistics for IFOM across domain strata. The IFOM CSE scores are reported in the form of median (interquartile range [IQR]) and mean (SD), as are the cGPA scores. These continuous variables are also summarized graphically using box plots. Linearity between cGPA and IFOM CSE was assessed by a lowess (robust locally weighted linear regression) curve.Citation31 To assess the independent effect of each variable on IFOM CSE, backward elimination linear regression was performed. All variables found to be significantly associated (P<0.10) with IFOM CSE by preliminary univariable analyses were used in this iterative procedure. Variables were eliminated in a stepwise fashion based on an exit probability of 0.20. Due to potential confounding, age and gender were forced into the final model, irrespective of statistical significance. Interactions between retained variables were assessed by likelihood ratio tests (P<0.10), and multicollinearity was investigated by the calculation of variance inflation factors (VIFs). The predictive ability of the final multivariable model and the explanatory value of the cGPA were assessed using adjusted R-squared statistics. All observations were assessed for excessive influence by the calculation of DFBETA statistics.Citation32 Modeling results are reported as unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients, with accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was then used to measure the discriminative utility of cGPA to identify students at risk of underachieving on the IFOM CSE, as specified by the ISC. These analyses were facilitated by first performing logistic regression modeling. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata, version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In total, 428 students were involved in the study. Students were more likely to be aged between 25 and 29 years (49.41%), to be male (57.71%), and to have achieved a GPA of 5.00–5.99 (on a 7-point scale) in their final MBBS semester (46.60%) (). Students were predominately domestic (70.96%), spoke English at home (85.28%), and had enrolled in 2009 (85.95%). Mean IFOM CSE scores ranged from a high of 569 (SD: 104) for students with a final semester GPA of at least 6.00 to a low of 460 (SD: 86) for students who had enrolled post-2009. Missing data were negligible, with covariate data (ie, age) collected on all but one student.

Table 1 Characteristics of study subjects (n=428)

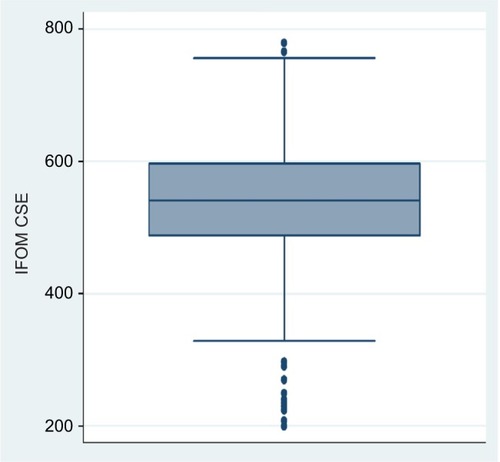

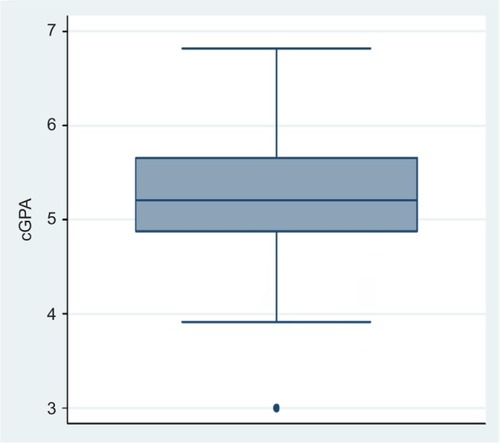

The distributions of the dependent variable, namely, IFOM CSE performance, and the primary independent variable of interest, namely, cGPA, are presented by box plots in and , respectively. IFOM CSE score varied from 208 to 779 (median: 541; IQR: 110), while the cGPA varied from 3.0 to 6.82 (median: 5.21; IQR: 0.79). The data were screened for outliers. Using box plot analyses, 3 cGPA and 21 IFOM CSE outliers were detected (defined as data points that are more than 1.5 IQRs from the rest of the sample). Of the latter, most outliers were low scores, with 19 students having an IFOM CSE score of less than 300 and 2 having an IFOM CSE score of 760. Removing these participants, however, did not alter any of the findings. Consequently, all reported results are based on the complete data set.

Figure 1 Box plot of IFOM CSE scores of students (n=428).

Figure 2 Box plot of cGPA scores of students (n=428).

Due to sample size, as well as the similarity between IFOM CSE mean and median (ie, less than 2% difference), regression estimates are not unduly biased, even though the normality assumption was not strictly satisfied as tested by the Shapiro–Francia W statistic (W=0.94; P<0.01).Citation33,Citation34

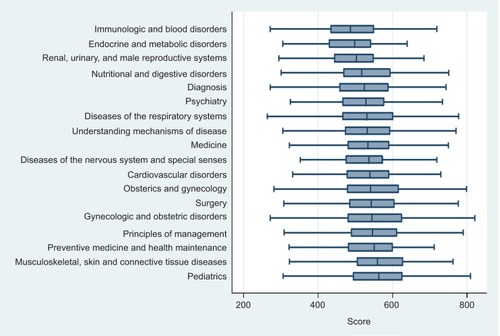

As unscaled median scores across the 18 domains varied from a low of 487 (IQR: 114) for Immunologic and Blood Disorders to a high of 563 (IQR: 130) for Pediatrics (). Scores for Diseases of the Nervous System and Special Senses (median: 536; IQR: 98) showed the least variation, and scores on Gynecologic and Obstetric Disorders (median: 544; IQR: 202) showed the most variation.

Figure 3 Box plots for IFOM CSE domain scores of students (n=428).

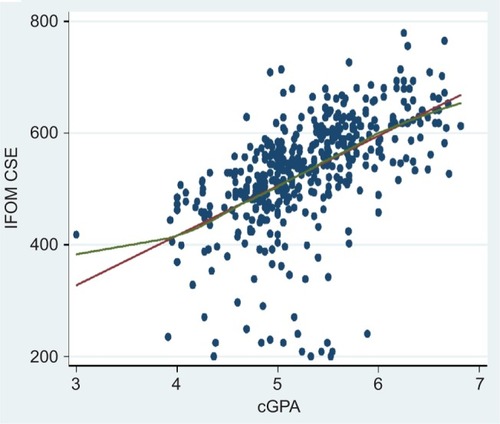

Justification for modeling the IFOM data by linear regression is seen in , wherein the lowess curve for the cGPA–IFOM relationship only deviates from the line of best fit for cGPA scores less than 4, providing evidence that the assumption of linearity has not been substantially violated.Citation35

Figure 4 IFOM CSE scores plotted against cGPA scores with line of best fit (red curve) and lowess fit (green curve) for students (n=428).

The results of the linear regression analyses are presented in . In addition to cGPA being strongly predictive of IFOM (nonstandardized regression coefficient [B]: 89.16; 95% CI: 75.85 to 102.47; P<0.01; adjusted R2: 29.30%), univariable analyses also identified year of MBBS enrollment, international student status, and language spoken at home as being significantly associated with IFOM CSE. Subsequently, a stepwise backward elimination procedure resulted in cGPA, year of MBBS enrollment, international status, language, age, and gender being incorporated into the multivariable linear regression model; the latter 2 being forced. All 2-way interactions were nonsignificant, and all VIFs were lower than 2, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a concern in interpreting the results.Citation36 After adjustment for model covariates, cGPA continued to be highly predictive of IFOM (B: 81.83; 95% CI: 68.13 to 95.53), as was International student status (B: –37.40; 95% CI: –57.85 to –16.96). Neither language, nor year of enrollment remained significant in the multivariable model. Comparison of the beta-coefficient of 0.50 for cGPA with the beta-coefficient of –0.17 for International student status indicated that the unique contribution of cGPA as a predictor of IFOM CSE was more than twice that of International student status. No DFBETA exceeded 1,Citation37 which suggests that no regression coefficient estimate was excessively influenced by any individual observation. Further evidence of the predictive strength of cCPA can be seen in comparing adjusted-R2 values. While 29.30% of the variation in IFOM CSE was attributable to cGPA, only 2.88% was due to the remaining covariates.

Table 2 Univariable and multivariable linear regression analyses for variables associated with IFOM CSE scores from 428 students at the University of Queensland in 2012

Logistic model building aims to include important variables and, at the same time, create a parsimonious and valid model. In our model, we used cGPA, the strongest predictor of IFOM CSE, to calculate area under receiver-operating characteristic curves (AROCs), as reported in . We present AROCs separately for domestic and international students, as International status was the second variable that reached statistical significance in our multivariable analysis (). Because of the large number of potential thresholds associated with cGPA, a cross sample of values that can be used in establishing a single threshold is shown in . cGPA thresholds that produced maximal discrimination between students likely to achieve ICS and those not were found to be 5.30 for domestic students (AROC: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.72 to 0.82) and 4.90 for international students (AROC: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.66 to 0.78).

Table 3 Area under ROC curves for varying cGPA thresholds for domestic and international students

Discussion

Principal findings

We examined the absolute and relative contributions of cGPA, final semester GPA, age, gender, year of MBBS enrollment, MBBS entry pathway, international student status, and language spoken at home in predicting students’ performance on the IFOM CSE. Based on the outcomes from the multivariable linear regression, we identified 2 variables, cGPA and international status, as being significantly associated with IFOM performance. Of the 2, the former was dominant, accounting for nearly one-third of the variance in IFOM CSE. A third variable (language spoken at home) had a near-significant association. With significant predictor variables identified, an ROC analysis found that international students had a lower threshold of risk than domestic students.

Comparison with previous literature

There is a large literature examining the prediction of academic performance of medical students on the USMLE Step 2 through the use of multivariable regression modeling.Citation21,Citation23,Citation26,Citation27,Citation38–Citation45 In comparison, only Wilkinson et alCitation30 have reported on the IFOM CSE. Our study used a multivariable regression approach to calculate independent effects, while Wilkinson et alCitation30 used a correlational analysis approach and thus did not adjust for possible confounding by model covariates.Citation30 Our results are consistent with the USMLE-related studies in that cGPA and international student status were found to be strongly predictive of IFOM CSE.Citation21,Citation23,Citation26,Citation30,Citation39–Citation41 Though not reaching statistical significance, we also found, similar to De Champlain et alCitation39 and Glaser et al,Citation40 that students who spoke English at home performed better. Unlike a number of earlier studies, we did not detect significant effects by age,Citation23,Citation42 gender,Citation26,Citation27,Citation38,Citation44,Citation45 or year of admission.Citation23

Limitations and strengths

Our study has strengths, which include its originality. To our knowledge, no prior study has developed a multivariable predictive model for IFOM performance or analyzed a subsequent risk assessment tool to identify students expected to not meet the IFOM ISC. A further strength of this study was its relatively large size. A sample size of more than 400 facilitated the examination of a variety of potential variables related to IFOM CSE. This was substantiated by a post hoc power analysis,Citation46 which indicated that the study was sufficiently powered to detect a significant association between cGPA and IFOM CSE, when adjusted for model covariates.

Some caveats need to be taken into account when interpreting our results. First, it was conducted at a single medical school, and the results may not be generalizable to other institutions. The strongest predictor of IFOM CSE performance was cGPA, but this measure is based on the MBBS course performance and examination scores at our medical school, and other schools may award grades and test scores differently. Second, we used our original sample to test the accuracy of the model, so it is possible our study overestimates the ability of the model to correctly classify a new observation. Third, as with all low-stake examinations, our estimates are subject to biases generated by lack of examinee motivation and low effort, rather than the hurrying-to-finish strategy used by examinees in a high-stakes context, such as the USMLE.Citation47 In defence of this, removal of low-scoring outliers did not change the association. Fourth, by using only IFOM CSE total scores, this study provides no information on the predictive accuracy of IFOM CSE domain scores. Lastly, there is potential for residual confounding,Citation48 due to unmeasured variables such as the scores on the Undergraduate Medical and Health Professions Admission Test (UMAT) and the Graduate Australian Medical School Admissions Test (GAMSAT). These were not available and were not included in the modeling.

Conclusion and recommendations

We conclude that cGPA is strongly correlated with scores on the IFOM CSE. This strong correlation suggests that the cGPA will have a high predictive value in identifying students at risk of poor IFOM CSE performance. Future research should determine the degree to which cGPA scores early in a student’s medical course predict subsequent outcomes, such as total IFOM CSE scores, specifically IFOM CSE domains. This study was necessarily limited to certain variables that were mostly sociodemographic, and other measures might have improved its predictive value. Future research should incorporate other measures and should broaden the focus from a single institution to include many institutions. Further study is needed to determine whether educational interventions to improve IFOM CSE scores can lead to improvements in subsequent test performance and other outcomes.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GreenDGOf Ants and MenThe Unexpected Side Effects of Complexity in SocietyBerlinSpringer-Verlag2014195209

- De ChamplainAFGrabovskyIScolesPVCollecting evidence of content validity for the International Foundations of Medicine Examination: an expert-based judgmental approachTeach Learn Med201123214414721516601

- MalasanosTHBurlingameJAMuirAAdvances in telemedicine in the 21st centuryAdv Pediatr20045113116915366773

- RuizJGMintzerMJLeipzigRMThe impact of e-learning in medical educationAcad Med200681320721216501260

- O’RiordanMRiainANDistance learning: linking CME and quality improvementMed Teach20042655956415763836

- KondroWEleven satellite campuses enter orbit of Canadian medical educationCMAJ200617546146216940255

- SchwartzHMStates Versus Markets: The Emergence of a Global EconomyBasingstokeMacmillan2000

- IredaleRThe migration of professionals: theories and typologiesInt Migr200139572619186395

- LeinsterSAssessment in medical trainingLancet20033629397177014643146

- DehmelAMaking a European area of lifelong learning a reality? Some critical reflections on the European Union’s lifelong learning policiesComp Educ20064214962

- KeelingRThe Bologna Process and the Lisbon Research Agenda: the European Commission’s expanding role in higher education discourseEur J Educ2006412203223

- DauphineeWDWood-DauphineeSThe need for evidence in medical education: the development of best evidence medical education as an opportunity to inform, guide, and sustain medical education researchAcad Med2004791092593015383347

- WilkinsonTJHudsonJNMccollGJHuWCJollyBCSchuwirthLWMedical school bench-marking – from tools to programmesMed Teach201537214615224989363

- NBME [webpage on the Internet]International Foundations of Medicine2014 Available from: http://www.nbme.org/Schools/iFoM/index.htmlAccessed July 12, 2014

- NBME2015 NBME Annual Report2015 Available from: http://www.nbme.org/PDF/Publications/2015Annual-Report.pdfAccessed December 8, 2015

- HoltzmanKZSwansonDBOuyangWDillonGFBouletJRInternational variation in performance by clinical discipline and task on the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 Clinical Knowledge componentAcad Med201489111558156225250743

- WilkinsonDA new paradigm for assessment of learning outcomes among Australian medical students: in the best interest of all medical studentsAust Med Stud J2014424547

- PhillipsJPWe must make the cost of medical education reasonable for everyoneAcad Med201388101404

- VarkeyPMuradMHBraunCGrallKJSaojiVA review of cost-effectiveness, cost-containment and economics curricula in graduate medical educationJ Eval Clin Pract20101661055106220630001

- BascoWTWayDPGilbertGEHudsonAUndergraduate institutional MCAT scores as predictors of USMLE step 1 performanceAcad Med20027710S13S1612377692

- DonnonTPaolucciEOViolatoCThe predictive validity of the MCAT for medical school performance and medical board licensing examinations: a meta-analysis of the published researchAcad Med20078210010617198300

- JonesRFThomae-ForguesMValidity of the MCAT in predicting performance in the first two years of medical schoolJ Med Educ1984594554646726764

- KleshenkiJSadikAKShapiroJIGoldJPImpact of preadmission variables on USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 performanceAdv Health Sci Educ2009146978

- MitchellKHaynesRKoenigJAAssessing the validity of the updated Medical College Admission TestAcad Med1994693944018166926

- HaistSAWilsonJFElamCLBlueAVFossonSEThe effect of gender and age on medical school performance: an important interactionAdv Health Sci Educ200053197205

- VeloskiJJCallahanCAXuGHojatMNashDBPrediction of students’ performance on licensing examinations using age, race, sex, undergraduate GPAs, and MCAT scoresAcad Med20007510S28S30

- SwygertKACuddyMMvan ZantenMHaistSAJobeACGender differences in examinee performance on the Step 2 Clinical Skills® data gathering (DG) and patient note (PN) componentsAdv Health Sci Educ2012174557571

- Van ZantenMBouletJRMcKinleyDWCorrelates of performance of the ECFMG Clinical Skills Assessment: influences of candidate characteristics on performanceAcad Med20037810S72S7414557101

- EdwardsDWilkinsonDCannyBJPearceJCoatesHDeveloping outcomes assessments for collaborative, cross-institutional benchmarking: progress of the Australian Medical Assessment CollaborationMed Teach201436213914724171466

- WilkinsonDSchaferJHewettDEleyDSwansonDGlobal benchmarking of medical student learning outcomes? Implementation and pilot results of the International Foundations of Medicine Clinical Sciences Exam at The University of Queensland, AustraliaMed Teach2013361626724164636

- ClevelandWSRobust locally weighted fitting and smoothing scatterplotsJ Am Stat Assoc197974829836

- BelsleyDAKuhEWelshRERegression Diagnostics: Identifying Influential Data and Sources of CollinearityNew YorkJohn Wiley & Sons1980

- LumleyTDiehrPEmersonSChenLThe importance of the normality assumption in large public health data setsAnnu Rev Public Health20022315116911910059

- RoystonPA single method for evaluating the Shapiro-Francia W test for non-normalityStatistician198332297300

- VittinghoffEGliddenDVShiboskiSCMcCullochCERegression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival, and Repeated Measures ModelsBerlinSpringer Science & Business Media2011

- MansfieldERHelmsBPDetecting multicollinearityAm Stat1982363a158160

- BollenKAJackmanRRegression diagnostics: an expository treatment of outliers and influential casesFoxJLongJSModern Methods of Data AnalysisNewbury Park, CASage Publications1990257291

- CaseSMBeckerDFSwansonDBPerformances of men and women on NBME Part I and Part II: the more things changeAcad Med19936810S25S278216622

- De ChamplainAFSwygertKSwansonDBBouletJRAssessing the underlying structure of the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 Test of Clinical Skills using confirmatory factor analysisAcad Med20068110S17S20

- GlaserKHojatMVeloskiJJBlacklowRSGoeppCEScience, verbal, or quantitative skills: which is the most important predictor of physician competence?Educ Psychol Meas199252395406

- KasuyaRTNaguwaGSGuerreroAPUSMLE performances in a predominantly Asian and Pacific Islander population of medical students in a problem-based learning curriculumAcad Med200378548349012742783

- OgunyemiDTaylor-HarrisDSFactors that correlate with the US Medical Licensure Examination Step-2 scores in a diverse medical student populationJ Natl Med Assoc20059791258126216296216

- RipkeyDRCaseSMSwansonDBMelnickLTBowlesNGaryEPerformance of examinees from foreign schools on the clinical science component of the United States Medical Licensing ExaminationScherpbierAvan der VleutenCRethansJvan der SteegAAdvances in Medical EducationDordrechtKluwer Academic Publishers1997175178

- SimonSRBuiADaySBertiDThe relationship between second-year medical students’ OSCE scores and USMLE Step 2 scoresJ Eval Clin Pract200713690190518070260

- SwansonDBCaseSMRipkeyDRMelnickDEBowlesLTGaryNEPerformance of examinees from foreign schools on the basic science component of the United States Medical Licensing ExaminationScherpbierAvan der VleutenCRethansJvan der SteegAAdvances in Medical EducationDordrechtKluwer Academic Publishers1997187190

- FaulFErdfelderELangAGBuchnerAG* Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciencesBehav Res Methods200739217519117695343

- BouletJRSmeeSMDillonGFGimpelJRThe use of standardized patient assessments for certification and licensure decisionsSimul Healthc200941354219212249

- BecherHThe concept of residual confounding in regression models and some applicationsStat Med19921113174717581485057