ABSTRACT

For the past 30 years, the Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) journal has both documented and instigated change in the field of AAC. We reviewed the papers published in the AAC journal from1985–2014 in order to identify trends in research and publication activities. Intervention research made up the largest proportion of the four types of research (i.e., intervention, descriptive, experimental, and instrument and measurement development) reported in the journal. Intervention research has most commonly focused on the individual with complex communication needs, and most frequently on younger individuals (aged 17 and younger) with developmental disabilities. While much has been learned in the past 30 years, there continues to be a need for high quality research in a large number of areas. There is a special need for reports of interventions with older individuals with complex communication needs as a result of acquired disabilities, and for information on effective interventions for the communication partners of persons with complex communication needs.

Introduction

My voice is now limitless

Words become notes

Blaring building blocks

Where I build my literary symphony

Which echoes throughout the world

(McLeod, Citation2008)

The field of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) has the primary goal of supporting the communication and participation of persons with complex communication needs (Beukelman, Citation1991; Blackstone, Williams, & Wilkins, Citation2007; Light & McNaughton, Citation2015; Mirenda, Citation1993; Williams, Krezman, & McNaughton, Citation2008). In the excerpt above, Lateef McLeod, a poet who uses AAC, describes the power of AAC in his interactions with the world (McLeod, Citation2008). Although the power of AAC is not always described as eloquently as it is here by McLeod, the importance of AAC to support communication and participation has been widely recognized and celebrated by persons with complex communication needs (Estrella, Citation2000; Prentice, Citation2000; B. Williams, Citation2000; M. Williams, Citation2004), as well as clinicians, educators, and researchers (Anderson, Balandin, & Clendon, Citation2011; Broberg, Ferm, & Thunberg, Citation2012; Calculator, Citation2013; Fried-Oken, Beukelman, & Hux, Citation2012; Hunt-Berg, Citation2005; Light & McNaughton, Citation2008). The papers published in the September and December issues of the AAC journal as a special 30th anniversary series provide clear evidence of the substantial gains in the field over the past 30 years in a wide range of areas, including (a) early intervention (Romski, Sevcik, Barton-Hulsey, & Whitmore, Citation2015), (b) AAC intervention for individuals with autism spectrum disorders (Ganz, Citation2015), (c) the language development of individuals who require aided communication (Smith, Citation2015), (d) the use of visual scene displays for people with aphasia (Beukelman, Hux, Dietz, McKelvey, & Weissling, Citation2015), (e) microswitch technology for children with profound and multiple disabilities (Roche, Sigafoos, Lancioni, O’Reilly, & Green, Citation2015), (f) communication partner instruction (Kent-Walsh, Murza, Malani, & Binger, Citation2015 [this issue]), and (g) speech output technologies for individuals with autism spectrum disorders (Schlosser & Koul, Citation2015 [this issue]).

Although the use of AAC strategies enjoys a long rich history (Beukelman & Mirenda, Citation2013; Zangari, Lloyd, & Vicker, Citation1994), organized research to investigate strategies to support the use of AAC, and publications to document this work, are a much more recent endeavor (Beukelman, Citation1997; Light & McNaughton, Citation2008; Mirenda, Citation1998). Although research activities can be documented in many forms (e.g., dissertations, conference presentations, research reports), the publication of peer-reviewed journal articles is the major method by which a field of research establishes the evidence base to guide practice, promotes awareness of research to the broader community, defines future research needs, and archives the findings for posterity (Prosser, Citation2013; Schlosser & Sigafoos, Citation2009).

In the early years of the AAC field, much of the information about AAC was developed and informally shared by clinicians (working to meet the needs of their clients) through workshops, and at the first ISAAC conferences (Light & McNaughton, Citation2008; Zangari, Kangas, & Lloyd, Citation1988). There was only limited formal coursework available in AAC (Koul & Lloyd, Citation1994; Ratcliff & Beukelman, Citation1995) and only a small amount of formal research activity (Zangari et al., Citation1988,Citation1994). A journal search for papers using the terms ‘augmentative communication’ or ‘augmentative and alternative communication’ yielded only eight journal articles for the 10-year period of 1975–1984.Footnote1

For the field of AAC, growth in published research followed the growing interest in strategies to support communication and participation for individuals with complex communication needs during the 1980s and 1990s (Mirenda, Citation1998). The launch of the AAC journal in 1985 furthered a growing interest in AAC research that continues to this day: A journal search of the most recent 10-year period (2005–2014) yielded 762 papers on the topic of AAC,Footnote2 providing clear evidence of the exponential growth that has taken place in both AAC research and publication activity.

The AAC journal has served to both document and instigate changes in technology, policy, and practice (Light & McNaughton, Citation2008). Although other fields and journals have increasingly recognized the importance of AAC (Chung, Carter, & Sisco, Citation2012; Frankoff & Hatfield, Citation2011; Ganz et al., Citation2012; Gona, Newton, Hartley, & Bunning, Citation2014; Londral, Pinto, Pinto, Azevedo, & De Carvalho, Citation2015), the AAC journal has continued to play a leadership role as the major publication venue for AAC research.

The past 30 years have seen many changes in the field of AAC, changes that were reflected in (and supported by) the AAC journal. We therefore chose to review the past 30 years of published work in the AAC journal in order to better understand both the history and the state of research in the field, and to explore how the research community might better serve the field in the future. We recognize that this focus on work published in the AAC journal may not be representative of the entire body of AAC research; however, it is clear that the AAC journal has served as the major repository for work on AAC. With these caveats in mind, we have provided a review of the research in the AAC journal, and highlighted information in three major areas: (a) the overall types of papers that were most frequently published during the 30-year period; (b) the types of research that were most frequently reported; and (c) for those papers that described intervention studies, the types of participants (e.g., disability group, age) that were involved.

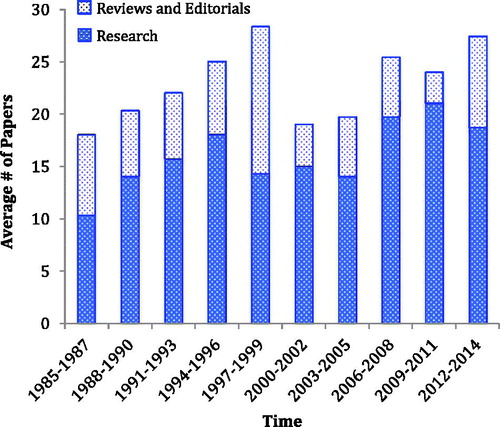

Papers Most Frequently Published

In order to describe the type of work that has appeared in the AAC journal, we first sorted all the papers into one of two categories:Footnote3 (a) original research (including descriptive, experimental-nonintervention, intervention, measurement and instrument development), and (b) research reviews and editorials (which also included forum notes). In presenting information on the types of papers published over time, we grouped the 30 years that we examined (1985–2014) into 3-year blocks, and then reported an average for each of the ten 3-year periods. shows the number of papers published in an average year for the 3-year period reported.

Figure 1. Number of research and review/editorial papers published between 1985 and 2014 (presented as average number of papers per year during 3-year time spans).

The first key finding is that the journal has grown significantly in the total number of articles published each year. Although there has been variation over time, more papers (n = 230) were published in the most recent 9 years (2006–2014) than in any 9-year period in the journal’s history. This is not surprising: The early editors faced many challenges in establishing the AAC journal at a time when, although there was clinical interest in the implementation of AAC (Zangari et al., Citation1994), only a small number of individuals were conducting and publishing AAC research (Beukelman, Citation1997; Mirenda, Citation1998). The strong foundation provided by these early editors and researchers/authors has supported the recognition for and the growth of the journal, and indeed the field of AAC, over time.

The second key finding is that the research category has grown significantly over the past 30 years, both in the number of research papers per year and as a proportion of all papers published. Clearly, it is a major function of the journal to publish original research because research serves to establish the evidence base for clinical practice and system development in AAC (Mirenda, Citation1998; Schlosser & Sigafoos, Citation2009). It is of interest to note that the average number of research papers published each year has almost doubled from the earliest years of the journal, from 10.3 to 18.7 papers per year. Research papers have also increased as a percentage of all articles published, from 66% for the first 9 years of the journal to 77% for the most recent 9 years of the journal, a statistic that compares favorably with other journals. For example, in a review of 11 special education journals, Mastropieri et al. (Citation2009) reported that 58% of the articles were coded as research and 42% were coded as “not research.”

While a strong research base is important, research reviews, editorials, and forum notes also have served a critical role. These papers have served to synthesize the research base as well as advance thinking and introduce innovative ideas to the field on topics such as early intervention (Branson & Demchak, Citation2009; Light & Drager, Citation2007), communicative competence (Beukelman, Citation1991; Light, Citation1997; Light & McNaughton, Citation2014), inclusion (Mirenda, Citation1996,Citation1993), partner training (Beukelman, Ball, & Fager, Citation2008; Binger et al., Citation2012; Kent-Walsh & McNaughton, Citation2005), and interventions for persons with acquired disabilities (Beukelman, Fager, Ball, & Dietz, Citation2007; Fox & Fried-Oken, Citation1996). Evidence of the impact of these papers can be clearly seen in the download statistics for the AAC journal: Six of the 10 most frequently read papers from 1999 to 2014 were systematic reviews, editorials, or forum notes (H. Parup, personal communication, 25 January 2015).

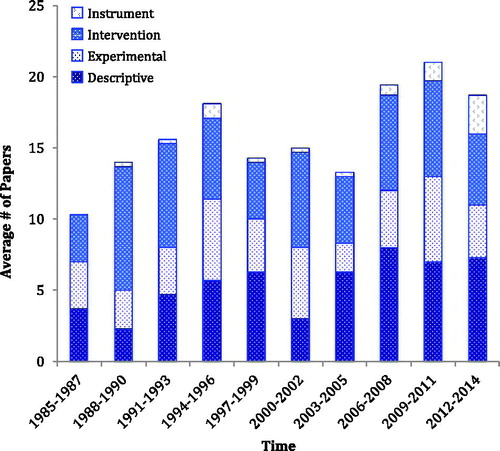

Types of Research Most Frequently Reported

For those papers that described research activities, we further coded each paper into one of four categories: Intervention studies investigated the impact of an independent variable (e.g., instruction, an AAC system) on the performance of research participants. For a paper to be coded as intervention research, the participants needed to be individuals who could benefit from the intervention (e.g., individuals with complex communication needs, typical communication partners). Also, data needed to be presented on some aspect of alterable participant performance (e.g., learning and use of symbols, use of communication partner skills) rather than some measured response to a device feature (e.g., intelligibility of synthesized speech). Descriptive studies featured information that was collected using observational, survey, or qualitative methods. Experimental studies most commonly described the effect of the manipulation of an independent variable (other than an intervention, per se) with individuals who would not normally make use of AAC (e.g., use of a text-entry scanning system by college students without disabilities) or measured a response to a device feature (e.g., measurement of visual attention by persons with disabilities to different display layouts). Studies coded as Instrument and measurement development focused on the development and evaluation of tools to assess the communication performance of individuals with complex communication needs and/or their communication partners. shows the number of papers published in each category, using the yearly average calculated for the ten 3-year periods.

Figure 2. Number and types of research papers published between 1985 and 2014 (presented as average number of papers per year during 3-year time spans).

Intervention Research

Approximately 37% of all research papers investigated the impact of intervention research. The number of intervention research papers can also be considered as a percentage of all papers (i.e., research and non-research) published. Using this latter approach, the percentage of all papers in the AAC journal that provide information on intervention research (i.e., 20%) would appear to be slightly higher than the average (16%) obtained in a review of 11 special education journals by Mastropieri et al. (Citation2009). Although the journal compares favorably with others in the fields of disability intervention, we join past editors and authors in calling for increased attention to the reporting of intervention research (Beukelman, Citation1985; Crystal, Citation1986; Mirenda, Citation2000).

It also is important to note that this review made use of a broad definition of intervention research. We included in this category studies that made use of experimental and quasi-experimental designs, as well as studies that provided information on outcomes using descriptive methods (e.g., surveys of participant impressions of the impact of an intervention).

Common topics in intervention research included evaluations of the effects of the introduction of new AAC systems or training for persons with complex communication needs (Beck, Stoner, & Dennis, Citation2009; Bourgeois, Dijkstra, Burgio, & Allen-Burge, Citation2001; Rowland & Schweigert, Citation2000; Soto, Yu, & Kelso, Citation2008), as well as training for their communication partners (Jonsson, Kristoffersson, Ferm, & Thunberg, Citation2011; Kent-Walsh, Binger, & Hasham, Citation2010; Trottier, Kamp, & Mirenda, Citation2011). These papers provide important information for the development of evidence-based intervention to support the use of AAC (Mirenda, Citation1998; Schlosser & Sigafoos, Citation2009).

Of the intervention studies published in Augmentative and Alternative Communication over the past 10 years, approximately half targeted simple requests for objects or activities, while only a very small number addressed psychosocial factors such as motivation, attitude, confidence, and resilience (Light & McNaughton, Citation2015). Conducting intervention research that targets valued skills in typical settings is a widely recognized challenge. Snell et al. (Citation2010), in their review of 20 years of communication intervention research with individuals with severe intellectual and developmental disabilities (published in a wide variety of journals), reported that, in approximately 40% of the studies, the intervention was delivered in decontextualized settings, removed from the natural environment; and in more than 50% of the studies, the intervention was delivered by a researcher, not a natural communication partner. Furthermore, a review of recently published intervention research (2005–2014) in the AAC journal revealed that the length of the intervention was less than 6 weeks in more than 60% of the studies (Light & McNaughton, Citation2015). The challenge for future researchers will be to examine the impact of interventions targeting a wide range of communicative functions, skills, and psychosocial factors (Light & McNaughton, Citation2014), in the natural environment, with typical communication partners, over an extended period of time.

Descriptive

The second largest number of research articles published in the AAC journal (approximately 34% of all research papers) were coded as descriptive. As with the research category overall, this category has grown in terms of the number of papers published over the past 30 years. Although there has been some variation from year-to-year, on average the proportion of descriptive papers published (as a percentage of total research papers) has shown a modest increase over time. Recently, there has been an increase in the publication of qualitative research (Balandin & Goldbart, Citation2011), from less than one qualitative study per year in the early years of AAC, to more than three per year during the past 5 years.

The descriptive studies published in AAC have covered a wide range of topics, including (a) descriptions of interactions between persons who use AAC and communication partners (Light, Collier, & Parnes, Citation1985a,b; Light, Binger, & Kelford Smith, Citation1994; Soto, Hartmann, & Wilkins, Citation2006; Sundqvist & Rönnberg, Citation2010), (b) analysis of the spoken language of persons without disabilities (Balandin & Iacono, Citation1999; Marvin, Beukelman, & Bilyeu, Citation1994; Stuart, Beukelman, & King, Citation1997), (c) surveys of AAC system use (Angelo, Kokoska, & Jones, Citation1996; Angelo, Jones, & Kokoska, Citation1995; Johnson, Inglebret, Jones, & Ray, Citation2006), and (d) focus group studies of the life experiences of persons who use AAC and their partners (Anderson, Balandin, & Clendon, Citation2011; Hemsley & Balandin, Citation2004; McNaughton et al., Citation2008; Rackensperger, Krezman, McNaughton, Williams, & D’Silva, Citation2005). Descriptive research is an important first step in better understanding the nature of a phenomenon, and this research serves as a foundation for the development of future effective interventions (Bereiter & Scardamalia, Citation2013). It will be critical however, to insure that the field of AAC not only generates descriptive research as a foundation but also uses the data to develop new interventions and moves forward to test the effectiveness of these interventions (Sanson-Fisher, Campbell, Htun, Bailey, & Millar, Citation2008).

Experimental

The third largest category of research was coded as experimental (approximately 25%). These papers describe the outcome of an experiment in which an independent variable (other than an intervention) is manipulated, with the goal of determining the relationship between the variable being manipulated (e.g., the length of a message) and some other variable (e.g., the reported preference of the listener). Frequently addressed topics in this category include the ease of learning for different symbol systems (e.g., Fuller & Lloyd, Citation1987; Luftig & Bersani, Citation1985; Yovetich & Young, Citation1988), the intelligibility of synthesized speech (e.g., Higginbotham, Drazek, Kowarsky, Scally, & Segal, Citation1994; McNaughton, Fallon, Tod, Weiner, & Neisworth, Citation1994; Venkatagiri, Citation1994a), and the impact of different methods of text entry (e.g., Venkatagiri, Citation1994b, Citation1999).

In the initial stages of AAC technology development, it is not uncommon to investigate the use of a new AAC technique with people without disabilities in order to gain insight into some of the human-factors challenges associated with the use of the device. This approach is not without controversy (Bedrosian, Citation1995; Higginbotham, Citation1995); ultimately, it is critical to gather information on the use of a device with its intended audience – individuals with complex communication needs. At the same time, these early studies have often served as important first steps in the development of innovative technologies and research protocols (Drager & Light, Citation2010; Hetzroni & Lloyd, Citation2000; Wilkinson, Carlin, & Jagaroo, Citation2006).

Instrument and Measurement Development

Those papers that described and provided data on the development of new assessment tools were coded as instrument and measurement development and made up approximately 7% of the research papers published in the AAC journal between 1985 and 2014. Frequently examined areas for the development of measurement tools included the communication performance of individuals who use AAC (Franklin, Mirenda, & Phillips, Citation1996; McDougall, Vessoyan, & Duncan, Citation2012; Snell, Citation2002), as well as the performance of their communication partner (Broberg, Ferm, & Thunberg, Citation2012; Delarosa et al., Citation2012). This topic has been a growing area of interest for the AAC journal: There were five papers published in this category in the first 15 years of the journal (1985–1999); there have been 14 papers in this category in the most recent 15-year period (2000–2014).

AAC interventions (and intervention research) are often very challenging, in part because of the heterogeneity of the population of persons who use AAC, the complexity of AAC systems and interventions, and the intricate nature of the communication process (Light, Citation1999). It will be critical to identify measurement tools that are reliable and valid for the question being addressed and can be used for both formative and summative assessment activities.

Types of Interventions Most Frequently Reported

Over the 30 years of the AAC journal, a wide variety of interventions, with a wide variety of participants, have been reported. Intervention studies were categorized based on three factors: the target of the intervention (i.e., person with complex communication needs and/or the communication partner), the identified disability for the person with complex communication needs (as appropriate), and the age of the person with complex communication needs.

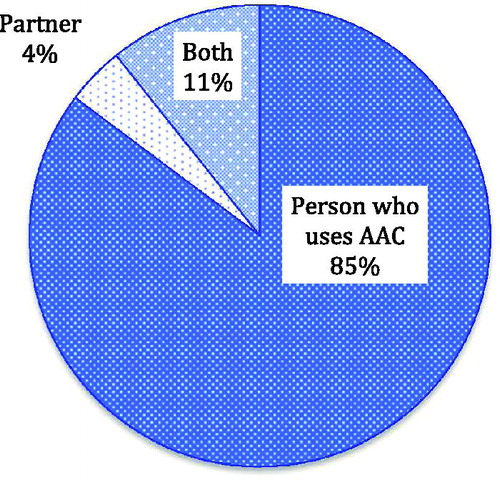

Participants in Intervention Research

In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of the importance of considering and providing appropriate supports for both the person with complex communication needs, and his or her partner in an interaction (Blackstone et al., Citation2007; Kent-Walsh & McNaughton, Citation2005; Kent-Walsh, Murza, Malani, & Binger, Citation2015). shows the proportion of studies targeting change in persons with complex communication needs and/or their communication partners for the years 1985–2014.

Figure 3. Focus of intervention as a percentage of intervention research papers published between 1985 and 2014.

When considering the entire 30-year period, the great majority of interventions (over 85%) were directed solely towards people who used AAC. Although training for the communication partner (or both) was the focus of only 15% of intervention research, this has been a growing area of interest in recent years. While only seven studies targeting behavior change by the communication partner were published between 1985 and 1999, 24 were published between 2000 and 2014, reflecting a growing awareness that AAC intervention is most effective when it addresses the communication skills of both the person with complex communication needs and the communication partner.

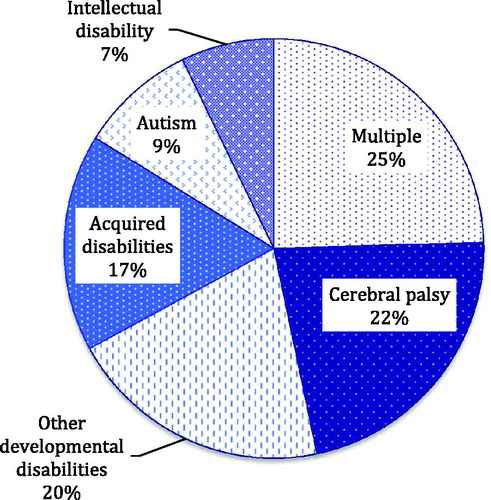

Population Focus

There is a growing international awareness that AAC can have a powerful impact for people with a wide range of disability types (Beukelman et al., Citation2015; Ganz, Citation2015; Tate & Happ, Citation2014; Roche, Sigafoos, Lancioni, O'Reilly, & Green, 2015; Romski, Sevcik, Barton-Hulsey & Whitmore, Citation2015).

shows that the research published in AAC has given much greater attention to those with developmental disabilities (83%) than those with acquired disabilities (17%), with the greatest number of studies focused on individuals with multiple disabilities (25%) and cerebral palsy (22%). One notable change for the AAC journal over time is the increased attention to intervention research with persons with autism: There were three studies published on this topic in AAC in the 15-year period between 1985–1999, while there were 12 studies published in the 15-year period between 2000 and 2014.

Figure 4. Percentage of intervention research papers published between 1985 and 2014 that included an individual with the listed disability.

It is difficult to compare the data on the populations addressed in the AAC journal with the data on the prevalence of these groups in the total population. Although there are data on the number of individuals with cerebral palsy, for example, the data on the percentage of individuals with cerebral palsy who require AAC are often unclear. It is also possible that the studies in the AAC journal are not representative of AAC research overall. For example, it is possible that research on individuals with certain disabilities (e.g., acquired disabilities, autism spectrum disorders, intellectual disabilities) is more likely to be published in disability-specific journals (e.g., Dietz, Hux, McKelvey, Beukelman, & Weissling, Citation2009; Ganz et al., Citation2012; Snell et al., Citation2010).

Age Groups

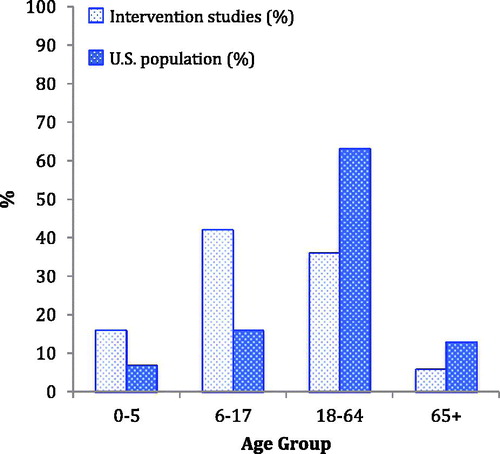

provides a comparison of the number of studies published in AAC that included participants from a particular age group. The results provide evidence that school-age and younger children have received more attention than adult populations, proportional to their representation in the population.Footnote4 Although there is more intervention research with these younger age groups, the message should not be that this area has received undue attention. This is the aggregated data for a 30-year period, and represents less than four intervention studies per year focused on persons who require AAC ages 17 and younger. There are a wide range of important intervention questions that need to be addressed for this population (Light & Drager, Citation2007; Romski et al., Citation2015; Smith, Citation2005). In addition, early intervention research is especially important for both ethical and practical reasons (Light & McNaughton, Citation2012; Romski et al., Citation2015). There is a responsibility to intervene as soon as there is reason to think that communication development is at risk (Williams et al., Citation2008), and early intervention with AAC strategies for both the child with complex communication needs and his or her communication partner has been demonstrated to have a positive impact that can help to reduce the lifelong impact of a disability (Kent-Walsh et al., Citation2015; Romski et al., Citation2015).

Figure 5. Percentage of intervention research papers published between 1985 and 2014 that included an individual from the listed age group.

As illustrates, only a relatively small number of intervention studies have been published in AAC examining intervention for individuals aged 18 and above. There are critical questions to be addressed for this population with respect to supporting participation in post-secondary education, employment, and independent living (Bryen, Citation2008; Collier, McGhie-Richmond, Odette, & Pyne, Citation2006; Huer, Citation1991; Stancliffe et al., Citation2010). We have only a limited understanding of how to provide effective interventions for individuals with developmental disabilities who will face changing life situations (e.g., independent living, adult relationships) as they age (Balandin & Morgan, Citation1997,Citation2001), or those who acquire the need for AAC at age 65 and older (Beukelman et al., Citation2007; Fried-Oken, Beukelman, & Hux, Citation2012). The paucity of research focused on older individuals is deeply problematic; the likelihood that an individual will experience a condition resulting in severe communication disabilities increases as he or she grows older, and there are more individuals in the United States with severe communication disabilities over the ages of 65 than there are between the ages of 6 and 14 (Brault, Citation2012). Although there has been exciting work demonstrating the positive impact of AAC for individuals who develop complex communication needs later in life (Beukelman, Hux, Dietz, McKelvey, & Weissling, Citation2015; Dietz et al., Citation2013; Fried-Oken et al., Citation2012), many important unanswered questions remain.

Conclusion and Future Research Directions

Many have contributed to the first 30 years of AAC and can take pride in the achievements of the journal. Since 1985, the AAC journal has served as the main forum for published work in the field of AAC, and has contributed both to the documentation of past successes and the identification of new areas in need of intervention. A rank ordering of those journals that published papers on AAC during the 10-year period of 2005–2014 provides evidence that more articles on AAC appeared in the AAC journal than the next 15 journals combined.Footnote5

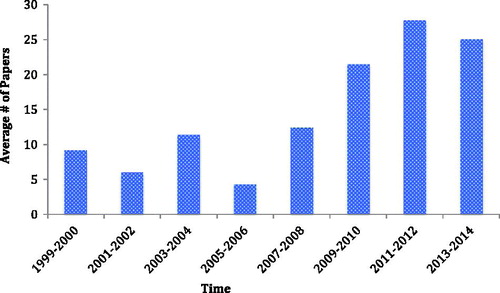

The growth in the field of AAC has been documented not only in the number of papers published (see ) but also the extent to which those papers document international interest (and collaboration) in augmentative and alternative communication. shows the increase in international collaboration in the journal over the past 15 years and provides data on the percentage of papers that included authors from more than one country.

Figure 6. International collaboration as represented by number of all papers published between 1999 and 2014 that included authors from two or more countries (presented as average number of papers per year during 2-year time spans).

Further evidence of increasing diversity in authorship is evidenced by the fact that since 2005, there have been at least 10 papers published in which a person with complex communication needs contributed as a co-author.

Viewing the AAC field generally and the journal specifically from a 30-year vantage point provides an opportunity to see how lines of research have grown and changed over time; how early descriptive work has provided a foundation for later intervention research; and, ultimately, how ongoing efforts are needed to support adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices. Many of the systematic reviews in the special 30th anniversary series trace their roots to the early days of AAC. For example, the early descriptive work on interaction between young children and their parents and teachers (e.g., Light et al., Citation1985a,Citation1985b; Rowland, Citation1990) provided the foundation for the recognition of communication as a reciprocal process between communication partners (e.g., Beukelman & Mirenda, Citation2013; Blackstone et al., Citation2007). Next, a growing number of research projects examined the impact of training partners on the success of communicative exchanges (e.g., Berry, Citation1987; Hunt, Alwell, & Goetz, Citation1991; McNaughton & Light, Citation1989). Kent-Walsh et al. (Citation2015) document how this field of research has grown over time and how partner training is now widely recognized as a key component of effective interventions (e.g., American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Beukelman & Mirenda, Citation2013). Similarly, the early technical work to assess and improve the intelligibility of synthesized speech (e.g., Higginbotham et al., Citation1994; Mirenda & Beukelman, Citation1987; Venkatagiri, Citation1994a) has continued on to an examination of how the use of this technology impacts the learning of new communication skills (e.g., Schlosser & Koul, Citation2015). It is also interesting to note how many of the early issues of concern remain relevant. One of the first research papers to appear in the AAC journal dealt with the challenges of obtaining funding for AAC systems (Beukelman, Yorkston, & Smith, Citation1985). Although dramatic progress has been made in this area, it continues to be an area that has required ongoing vigilance and advocacy to promote access to needed assistive technologies (Department for Education, UK, Citation2013; Patient Provider Communication, Citation2015).

The breadth and depth of the papers that are part of this 30th anniversary celebration make it clear that much progress has been made, but that many critical questions remain; these are well documented in the papers by Beukelman et al. (Citation2015); Ganz (Citation2015); Kent-Walsh et al. (Citation2015); Roche et al. (Citation2015); Romski et al. (Citation2015); Schlosser and Koul (Citation2015); and Smith (Citation2015). As we depart our role as editors, we encourage future authors to “dream big” and to conduct the research that addresses the key clinical and intervention issues that face the field of AAC. This will require the use of innovative methodologies, collaboration across disciplines, and partnerships amongst researchers, clinicians, and persons who use AAC across the world. The authors of the 30th anniversary papers have done a masterful job of synthesizing the remarkable progress made in the past 30 years and have set the stage for an exciting future. We wish to thank, once again, all of those who have played a role in supporting the development of the AAC journal throughout the years, and to welcome Martine Smith in her new role as Editor of the journal. The next 30 years hold great promise for the field of AAC and for the AAC journal!

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Susannah Boyle, Danisha Bernard, Erica Bronstein, Sarah Dubrow, Becky Frank, Felicia Giambalvo, Francesca Livi, Olivia Proper, Emilee Rehm, Sarah Rogers, Emily Strauss, and Megan Thomas for their assistance with this manuscript.

The contents of this paper were developed, in part, under a grant (The RERC on AAC) from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) [grant number H133E140026]. However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the funding agency, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Notes

1. This search was conducted using the title and abstract fields for 1975–1984 (Web of Science, 2015).

2. This search was conducted using the title and abstract fields for 2005–2014 (Web of Science, 2015).

3. Although we developed coding categories and definitions, and conducted informal checks for agreement, this paper is an informal review of research and we did not collect data on formal agreement checks.

4. In examining information on the relative size of different age groups, it is difficult to select an appropriate comparison statistic. For example, the national median age in the United States is 37.6 (Central Intelligence Agency, Citation2013) although in developing countries, the population is much younger (e.g., in Kenya, the national median age is 19.1). A comparison was made with the US population because much of the intervention research published in AAC has taken place in the United States, Canada, and the countries of the European Union, all of which share a similar demographic profile with respect to the relative size of the different age groups.

5. This search was conducted by examining the journal title for articles that included the words “augmentative and alternative communication” in the title or abstract fields for 2005–2014 (Web of Science, 2015).

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2015a). Aphasia (Practice Portal). www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Aphasia/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (2015b). Autism (Practice Portal). www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Autism/

- Anderson, K., Balandin, S., & Clendon, S. (2011). “He cares about me and I care about him.” Children’s experiences of friendship with peers who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27, 77–90.

- Angelo, D. H., Kokoska, S. M., & Jones, S. D. (1996). Family perspective on augmentative and alternative communication: Families of adolescents and young adults. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 12, 13–22.

- Angelo, D., Jones, S., & Kokoska, S. (1995). Family perspective on augmentative and alternative communication: Families of young children. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 11, 193–202.

- Balandin, S., & Goldbart, J. (2011). Qualitative research and AAC: Strong methods and new topics. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27, 227–228.

- Balandin, S., & Iacono, T. (1999). Crews, wusses, and whoppas: Core and fringe vocabularies of Australian meal-break conversations in the workplace. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 15, 95–109.

- Balandin, S., & Morgan, J. (1997). Adults with cerebral palsy: What’s happening? Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 22, 109–124.

- Balandin, S., & Morgan, J. (2001). Preparing for the future: Aging and alternative and augmentative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 17, 99–108.

- Beck, A. R., Stoner, J. B., & Dennis, M. L. (2009). An investigation of aided language stimulation: Does it increase AAC use with adults with developmental disabilities and complex communication needs? Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 25, 42–54.

- Bedrosian, J. (1995). Limitations in the use of nondisabled subjects in AAC research. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 11, 6–10.

- Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (2013). The psychology of written composition. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Berry, J. (1987). Strategies for involving parents in programs for young children using augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 3, 90–93.

- Beukelman, D. (1985). “The weakest ink is better than the strongest memory.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 1, 55–57.

- Beukelman, D. (1991). Magic and cost of communicative competence. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 7, 2–10.

- Beukelman, D. (1997). A learning experience. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 13, 205–206.

- Beukelman, D., & Mirenda, P. (2013). Augmentative and Alternative Communication (4th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Beukelman, D. R., Ball, L. J., & Fager, S. (2008). An AAC personnel framework: Adults with acquired complex communication needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24, 255–267.

- Beukelman, D. R., Fager, S., Ball, L., & Dietz, A. (2007). AAC for adults with acquired neurological conditions: A review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23, 230–242.

- Beukelman, D. R., Hux, K., Dietz, A., McKelvey, M., & Weissling, K. (2015). Using visual scene displays as communication support options for people with chronic, severe aphasia: A summary of AAC research and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31, 234–245.

- Beukelman, D., Yorkston, K., & Smith, K. (1985). Third-party payer response to requests for purchase of communication augmentation systems: a study of Washington State. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 1, 5–9.

- Binger, C., Ball, L., Dietz, A., Kent-Walsh, J., Lasker, J., Lund, S., … Quach, W. (2012). Personnel roles in the AAC assessment process. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28, 278–288.

- Blackstone, S., Williams, M. P., & Wilkins, D. P. (2007). Key principles underlying research and practice in AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23, 191–203.

- Bourgeois, M., Dijkstra, K., Burgio, L., & Allen-Burge, R. (2001). Memory aids as an augmentative and alternative communication strategy for nursing home residents with dementia. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 17, 196–210.

- Branson, D., & Demchak, M. (2009). The use of augmentative and alternative communication methods with infants and toddlers with disabilities: A research review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 25, 274–286.

- Brault, M. (2012). Americans with disabilities: 2010 (pp. 70–131). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

- Broberg, M., Ferm, U., & Thunberg, G. (2012). Measuring responsive style in parents who use AAC with their children: Development and evaluation of a new instrument. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28, 243–253.

- Bryen, D. N. (2008). Vocabulary to support socially-valued adult roles. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24, 294–301.

- Calculator, S. N. (2013). Use and acceptance of AAC systems by children with Angelman Syndrome. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 26, 557–567.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2013). The world fact book 2013–14. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2177.html

- Chung, Y.-C., Carter, E. W., & Sisco, L. G. (2012). Social interactions of students with disabilities who use augmentative and alternative communication in inclusive classrooms. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117, 349–367.

- Collier, B., McGhie-Richmond, D., Odette, F., & Pyne, J. (2006). Reducing the risk of sexual abuse for people who use augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 22, 62–75.

- Crystal, D. (1986). ISAAC in chains: The future of communication systems. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 2, 140–145.

- Delarosa, E., Horner, S., Eisenberg, C., Ball, L., Renzoni, A. M., & Ryan, S. E. (2012). Family Impact of Assistive Technology Scale: Development of a measurement scale for parents of children with complex communication needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28, 171–180.

- Department for Education, UK (2013). The future of AAC services in England – a framework for equitable and effective commissioning. http://www.communicationmatters.org.uk/dfe-aac-project

- Dietz, A., Hux, K., McKelvey, M. L., Beukelman, D. R., & Weissling, K. (2009). Reading comprehension by people with chronic aphasia: A comparison of three levels of visuographic contextual support. Aphasiology, 23, 1053–1064.

- Dietz, A., Thiessen, A., Griffith, J., Peterson, A., Sawyer, E., & McKelvey, M. (2013). The renegotiation of social roles in chronic aphasia: Finding a voice through AAC. Aphasiology, 27, 309–325.

- Drager, K. D. R., & Light, J. C. (2010). A comparison of the performance of 5-year-old children with typical development using iconic encoding in AAC systems with and without icon prediction on a fixed display. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 26, 12–20.

- Estrella, G. (2000). Confessions of a blabber finger. In M. Fried-Oken & H. Bersani (Eds.), Speaking up and spelling it out (pp. 31–45). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Fox, L., & Fried-Oken, M. (1996). AAC Aphasiology: Partnership for future research. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 12, 257–271.

- Franklin, K., Mirenda, P., & Phillips, G. (1996). Comparisons of five symbol assessment protocols with nondisabled preschoolers and learners with severe intellectual disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 12, 63–77.

- Frankoff, D. J., & Hatfield, B. (2011). Augmentative and alternative communication in daily clinical practice: Strategies and tools for management of severe communication disorders. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 18, 112–119.

- Fried-Oken, M., Beukelman, D. R., & Hux, K. (2012). Current and future AAC research considerations for adults with acquired cognitive and communication impairments. Assistive Technology, 24, 56–66.

- Fuller, D., & Lloyd, L. (1987). A study of physical and semantic characteristics of a graphic symbol system as predictors of perceived complexity. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 3, 26–35.

- Ganz, J. B. (2015). AAC interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31, 203–214.

- Ganz, J. B., Earles-Vollrath, T. L., Heath, A. K., Parker, R. I., Rispoli, M. J., & Duran, J. B. (2012). A meta-analysis of single case research studies on aided augmentative and alternative communication systems with individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 60–74.

- Gona, J. K., Newton, C. R., Hartley, S., & Bunning, K. (2014). A home-based intervention using augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) techniques in rural Kenya: What are the caregivers’ experiences? Child: Care, Health and Development, 40, 29–41.

- Hemsley, B., & Balandin, S. (2004). Without AAC: The stories of unpaid carers of adults with cerebral palsy and complex communication needs in hospital. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 20, 243–258.

- Hetzroni, O., & Lloyd, L. (2000). Shrinking Kim: Effects of active versus passive computer instruction on the learning of element and compound Blissymbols. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 16, 95–106.

- Higginbotham, D. J. (1995). Use of nondisabled subjects in AAC research: Confessions of a research infidel. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 11, 2–5.

- Higginbotham, D. J., Drazek, A., Kowarsky, K., Scally, C., & Segal, E. (1994). Discourse comprehension of synthetic speech delivered at normal and slow presentation rates. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 191–202.

- Huer, M. B. (1991). University students using augmentative and alternative communication in the USA: A demographic study. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 7, 231–239.

- Hunt-Berg, M. (2005). The Bridge School: Educational inclusion outcomes over 15 years. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 21, 116–131.

- Hunt, P., Alwell, M., & Goetz, L. (1991). Interacting with peers through conversation turn taking with a communication book adaptation. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 7, 117–126.

- Johnson, J. M., Inglebret, E., Jones, C., & Ray, J. (2006). Perspectives of speech language pathologists regarding success versus abandonment of AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 22, 85–99.

- Jonsson, A., Kristoffersson, L., Ferm, U., & Thunberg, G. (2011). The ComAlong communication boards: Parents’ use and experiences of aided language stimulation. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27, 103–116.

- Kent-Walsh, J., Binger, C., & Hasham, Z. (2010). Effects of parent instruction on the symbolic communication of children using augmentative and alternative communication during storybook reading. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19, 97–107.

- Kent-Walsh, J., & McNaughton, D. (2005). Communication partner instruction in AAC: Present practices and future directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 21, 195–204.

- Kent-Walsh, J., Murza, K. A., Malani, M. D., & Binger, C. (2015). Effects of communication partner instruction on the communication of individuals using AAC: A meta-analysis. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31, 271–284.

- Koul, R. K., & Lloyd, L. L. (1994). Survey of professional preparation in augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) in speech-language pathology and special education programs. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 3, 13.

- Light, J. (1997). “Communication is the essence of human life”: Reflections on communicative competence. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 13, 61–70.

- Light, J. (1999). Do augmentative and alternative communication interventions really make a difference?: The challenges of efficacy research. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 15, 13–24.

- Light, J., Binger, C., & Kelford Smith, A. (1994). Story reading interactions between preschoolers who use AAC and their mothers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 255–268.

- Light, J., Collier, B., & Parnes, P. (1985a). Communicative interaction between young nonspeaking physically disabled children and their primary caregivers: Part I – Discourse patterns. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 1, 74–83.

- Light, J., Collier, B., & Parnes, P. (1985b). Communicative interaction between young nonspeaking physically disabled children and their primary caregivers: Part II – Communicative function. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 1, 98–107.

- Light, J., & Drager, K. (2007). AAC technologies for young children with complex communication needs: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23, 204–216.

- Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2008). Making a difference: A celebration of the 25th anniversary of the International Society for Augmentative and Alternative Communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24, 175–193.

- Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2012). The changing face of augmentative and alternative communication: Past, present and future challenges. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28, 197–204.

- Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2014). Communicative competence for individuals who require augmentative and alternative communication: A new definition for a new era of communication? Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30, 1–18.

- Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2015). Designing AAC research and intervention to improve outcomes for individuals with complex communication needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31, 85–96.

- Londral, A., Pinto, A., Pinto, S., Azevedo, L., & De Carvalho, M. (2015). Quality of life in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and caregivers: Impact of assistive communication from early stages. Muscle & Nerve, early on-line.

- Luftig, R., & Bersani, H. (1985). An investigation of two variables influencing Blissymbol learnability with nonhandicapped adults. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 1, 32–37.

- Marvin, C., Beukelman, D., & Bilyeu, D. (1994). Vocabulary-use patterns in preschool children: Effects of context and time sampling. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 224–236.

- Mastropieri, M. A., Berkeley, S., McDuffie, K. A., Graff, H., Marshak, L., Conners, N. A., … Cuenca-Sanchez, Y. (2009). What is published in the field of special education? An analysis of 11 prominent journals. Exceptional Children, 76, 95–109.

- McDougall, S., Vessoyan, K., & Duncan, B. (2012). Traditional versus computerized presentation and response methods on a structured AAC assessment tool. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28, 127–135.

- McLeod, L. H. (2008). A declaration of a body of love. Houston, TX: Atahualpa Press.

- McNaughton, D., Fallon, K., Tod, J., Weiner, F., & Neisworth, J. (1994). Effect of repeated listening experiences on the intelligibility of synthesized speech. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 161–168.

- McNaughton, D., & Light, J. (1989). Teaching facilitators to support the communication skills of an adult with severe cognitive disabilities: A case study. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 5, 35–41.

- McNaughton, D., Rackensperger, T., Benedek-Wood, E., Krezman, C., Williams, M. B., & Light, J. (2008). “A child needs to be given a chance to succeed”: Parents of individuals who use AAC describe the benefits and challenges of learning AAC technologies. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24, 43–55.

- Mirenda, P. (1993). AAC: Bonding the uncertain mosaic. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 9, 3–9.

- Mirenda, P. (1996). Sheltered employment and augmentative communication: An oxymoron? Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 12, 193–197.

- Mirenda, P. (1998). AAC: coming of age or over the hill? Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 14, 197–199.

- Mirenda, P. (2000). Where have all the intervention studies gone? Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 16, 207–207.

- Mirenda, P., & Beukelman, D. (1987). A comparison of speech synthesis intelligibility with listeners from three age groups. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 3, 120–128.

- Patient Provider Communication (2015). Medicare Funding of SGD/Gleason Act. Retrieved from http://www.patientprovidercommunication.org/article_58.htm

- Prentice, J. (2000). With communication, anything is possible. In M. Fried-Oken & H.A. Bersani (Eds.) Speaking up and spelling it out (pp. 207–214). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Prosser, D. C. (2013). Researchers and scholarly communications: An evolving interdependency. In D. Shorley & M. Jubb (Eds.), The future of scholarly communication. London, England, Facet Publishing.

- Rackensperger, T., Krezman, C., McNaughton, D., Williams, M. B., & D’Silva, K. (2005). “When I first got it, I wanted to throw it off a cliff”: The challenges and benefits of learning AAC technologies as described by adults who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 21, 165–186.

- Ratcliff, A., & Beukelman, D. (1995). Preprofessional preparation in augmentative and alternative communication: State-of-the-art report. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 11, 61–73.

- Roche, L., Sigafoos, J., Lancioni, G. E., O’Reilly, M. F., & Green, V. A. (2015). Microswitch technology for enabling self-determined responding in children with profound and multiple disabilities: A systematic review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31, 246–258.

- Romski, M., Sevcik, R. A., Barton-Hulsey, A., & Whitmore, A. S. (2015). Early intervention and AAC: What a difference 30 years makes. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31, 181–202.

- Rowland, C. (1990). Communication in the classroom for children with dual sensory impairments: Studies of teacher and child behavior. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 6, 262–274.

- Rowland, C., & Schweigert, P. (2000). Tangible symbols, tangible outcomes. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 16, 61–78.

- Sanson-Fisher, R. W., Campbell, E. M., Htun, A. T., Bailey, L. J., & Millar, C. J. (2008). We are what we do: Research outputs of public health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35, 380–385.

- Schlosser, R. W., & Koul, R. K. (2015). Speech output technologies in interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A scoping review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31, 285–309.

- Schlosser, R. W., & Sigafoos, J. (2009). Navigating evidence-based information sources in augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 25, 225–235.

- Smith, M. M. (2005). The dual challenges of aided communication and adolescence. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 21, 67–79.

- Smith, M. M. (2015). Language development of individuals who require aided communication: Reflections on state of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31, 215–233.

- Snell, M. (2002). Using dynamic assessment with learners who communicate nonsymbolically. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18, 163–176.

- Snell, M. E., Brady, N., McLean, L., Ogletree, B. T., Siegel, E., Sylvester, L., … Sevcik, R. (2010). Twenty years of communication intervention research with individuals who have severe intellectual and developmental disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 115, 364–380.

- Soto, G., Hartmann, E., & Wilkins, D. P. (2006). Exploring the elements of narrative that emerge in the interactions between an 8-year-old child who uses an AAC device and her teacher. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 22, 231–241.

- Soto, G., Yu, B., & Kelso, J. (2008). Effectiveness of multifaceted narrative intervention on the stories told by a 12-year-old girl who uses AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24, 76–87.

- Stancliffe, R. J., Larson, S., Auerbach, K., Engler, J., Taub, S., & Lakin, K. C. (2010). Individuals with intellectual disabilities and augmentative and alternative communication: Analysis of survey data on uptake of aided AAC, and loneliness experiences. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 26, 87–96.

- Stuart, S., Beukelman, D., & King, J. (1997). Vocabulary use during extended conversations by two cohorts of older adults. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 13, 40–47.

- Sundqvist, A., & Rönnberg, J. (2010). A qualitative analysis of email interactions of children who use augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 26, 255–266.

- Tate, J. & Happ, M.B. (2014). Participation in informed consent by critically ill patients can be enhanced by augmentative communication. In C106. Interprofessional topics in the provision of critical care. E (Vols. 1–271, pp. A5241–A5241). American Thoracic Society.

- Trottier, N., Kamp, L., & Mirenda, P. (2011). Effects of peer-mediated instruction to teach use of speech-generating devices to students with autism in social game routines. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27, 26–39.

- Venkatagiri, H. (1994a). Effect of sentence length and exposure on the intelligibility of synthesized speech. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 96–104.

- Venkatagiri, H. (1994b). Effect of window size on rate of communication in a lexical prediction AAC system. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 105–112.

- Venkatagiri, H. (1999). Efficient keyboard layouts for sequential access in augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 15, 126–134.

- Wilkinson, K. M., Carlin, M., & Jagaroo, V. (2006). Preschoolers’ speed of locating a target symbol under different color conditions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 22, 123–133.

- Williams, B. (2000). More than an exception to the rule. In M. Fried-Oken & H.A. Bersani, Jr (Eds.), Speaking up and spelling it out (pp. 246–254). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Williams, M. (2004). Confessions of a multi-modal man. Alternatively Speaking, 7(1), 6.

- Williams, M. B., Krezman, C., & McNaughton, D. (2008). “Reach for the stars”: Five principles for the next 25 years of AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24, 194–206.

- Yovetich, W., & Young, T. (1988). The effects of representativeness and concreteness on the “guessability” of Blissymbols. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 4, 35–39.

- Zangari, C., Kangas, K., & Lloyd, L. (1988). Augmentative and alternative communication: A field in transition. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 4, 60–65.

- Zangari, C., Lloyd, L., & Vicker, B. (1994). Augmentative and alternative communication: An historic perspective. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 27–59.