Abstract

Background: Opiate substitution treatment (OST) is the administration of opioids (methadone or buprenorphine) under medical supervision for opiate addiction. Several studies indicate a large unmet need for OST in general practice in Antwerp, Belgium. Some hurdles remain before GPs engage in OST prescribing.

Objectives: Formulate recommendations to increase engagement of GPs in OST, applicable to Belgium and beyond.

Methods: In 2009, an exploratory qualitative research was performed using focus group discussions and interviews with GPs. During data collection and analysis, purposive sampling, open and axial coding was applied. The script was composed around the advantages, disadvantages and conditions of engaging in OST in general practice.

Results: We conducted six focus groups and two interviews, with GPs experienced in prescribing OST (n = 13), inexperienced GPs (n = 13), and physicians from addiction centres (n = 5). Overall, GPs did not seem very willing to prescribe OST for opiate users. A lack of knowledge about OST and misbehaving patients creates anxiety and makes the GPs reluctant to learn more about OST. The GPs refer to a lack of collaboration with the addiction centres and a need of support (from either addiction centres or experienced GP-colleagues for advice). Important conditions for OST are acceptance of only stable opiate users and more support in emergencies.

Conclusion: Increasing GPs’ knowledge about OST and improving collaboration with addiction centres are essential to increase the uptake of OST in general practice. Special attention could be paid to the role of more experienced colleagues who can act as advising physicians for inexperienced GPs.

Key Messages

The most important hurdles for GPs to engage in OST seem to be a lack of knowledge on OST and support from addiction centres and experienced colleagues in providing treatment.

Improving referral and follow-up with addiction centres and emergency care is essential if OST in general practice is to increase.

Experienced physicians can act as advisors for inexperienced GPs wishing to engage in OST.

Introduction

Opiate substitution treatment (OST) is the administration of opioids (methadone or buprenorphine) under medical supervision for opiate addiction.[Citation1,Citation2] Recommendations from European studies suggest that more actors should be involved in taking on a patient on OST, among other GPs.[Citation3] Keen et al. have shown that OST is feasible and effective within the primary care setting.[Citation4,Citation5] OST in general practice has resulted in an improvement of social, mental and physical health, a lower rate of criminal convictions and no increase in methadone casualties compared to before the start of the treatment.[Citation4,Citation6,Citation7]

A national survey in England and Wales in 2001 showed that 51% of the responding GPs had seen at least one opiate user in the past four weeks, and half of those physicians prescribed OST for those patients.[Citation8] In Scotland, the number of GPs who prescribed OST decreased from 56% to 44% between 2000 and 2008.[Citation9,Citation10] A Swiss study in 2005 indicated that only 23.9% of GPs were willing to accept new patients for OST.[Citation11] From these results, we can assume that barriers remain to exist in GPs to accept OST patients in their general practice.

In 2013, The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) indicates that in Belgium 17 482 opiate users were receiving OST, 95% of whom were receiving methadone.[Citation12] It remains unclear how many of them currently seek treatment in general practices.

With 500 000 inhabitants, Antwerp is the second largest city in Belgium. The wastewater study shows that Antwerp has a large illegal drug scene when compared with other big cities in Europe.[Citation13,Citation14] In the past, the local government has expressed its concerns regarding the concentration of the drug scene in one area of the city, where the addiction centres were also situated.[Citation15] In 2009, one of the centres moved three kilometres away from the city centre.[Citation16] An alternative way to achieve a better spread of people who use drugs (PWUD) is to refer patients for methadone substitution treatment to a GP in their neighbourhood.[Citation17] Although this may seem desirable from a policy point of view, it may have certain advantages and disadvantages for patients and GPs as we will explore in this study.

Since December 2006, physicians in Belgium need to fulfil certain criteria when they prescribe OST to more than two patients. First, they need to prescribe OST according to the scientific guidelines and attend regular training sessions on the subject. Second, the physician has to register with an approved illegal drug treatment centre or network, which in turn notifies the authorized medical commission that monitors the prescribing habits of the GPs.[Citation18]

Australia, Germany and Belgium have indicated a considerable unmet demand for OST.[Citation19–22] In Antwerp (Belgium), the addiction centres report low outflow of opiate users and a 35% increase in physician consultations for OST between 2009 and 2013.[Citation16] Besides that, the average age of OST clients has increased from 39 to 41 years; 17% of OST clients are above the age of 50 and are mostly stable.[Citation16] This situation causes a strain on the client capacity in the addiction centres that can be relieved by making more referrals to local general practices. The aim of the current study was to explore ways to increase the uptake of OST in general practice in the region of Antwerp, Belgium.

Methods

Study design

We performed an exploratory qualitative study using focus group discussions (FGD) and interviews with GPs in Antwerp in 2009.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of the Antwerp University Hospital gave permission for this research project (B30020095443;02/02/09). All participants gave their verbal informed consent.

Selection of study subjects

We applied purposive sampling, i.e., interviewees were selected on the degree of involvement with methadone substitution. The sample was mixed by criteria of age, gender, type of practice (solo or group practice) and number of opiate patients in treatment. Homogeneity was striven for in the level of experience, i.e., FGDs were organized with GPs who had no previous experience in prescribing OST, and other FGDs with GPs who did (treated at least one patient on OST in the past year).

We also decided to perform two additional semi-structured interviews with GPs who had considerable experience in OST prescribing but would rather not participate in a FGD. Besides, since several topics remained unexplored in the FGDs with the GPs, an additional FGD was set up with the physicians from the addiction centres.

Data collection

The script was composed around the conditions for engagement in OST in general practice. An experienced interviewer (LS, female psychologist) moderated all FGDs and interviews. Two researchers (JF, female social worker and LP, female general practitioner) assisted and observed during the FGDs.

Data-analysis

All FGDs and interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed ad verbatim and were kept anonymous. The data analysis was performed using principles of grounded theory, namely purposive sampling, iteration during the data collection, and analysis. The data collection was finished when enough data had been collected to give a full description of the explored themes and, therefore, saturation was reached.[Citation23,Citation24]

Two researchers did the data analysis independently, using a procedure of open coding, followed by axial coding fitting the emerging codes into a coding scheme that conceptualized the data into an explanatory diagram.[Citation23–25] The software package NVivo 9 (QSR International) assisted the researchers during data analysis.

A language editing service checked the English language, and at least two authors checked the translations of the quotations.

Results

We conducted two FGDs with GPs experienced in prescribing OST (n = 13), three with inexperienced GPs (n = 13) and one with physicians from the specialized centres (five physicians from three different addiction centres). The mean age of the GPs was 46 years (). Two individual interviews were conducted with two GPs who had experience in prescribing OST but preferred not to attend the FGDs.

Table 1. Characteristics of the GPs and physicians from the addiction centres in the focus group discussions and interviews.

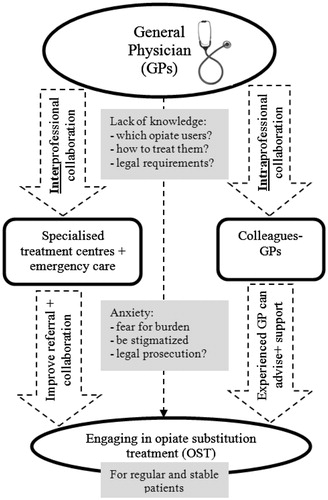

In exploring the perceptions and experiences of GPs and physicians from the addiction centres, we gained insight into the barriers that are encountered when prescribing OST in general practice. The diagram in represents the underlying relationship between the different barriers and possible routes to increase the uptake of OST in general practice. All aspects of the diagram are explained in the text and illustrated with quotes from the respondents in the interviews and FGDs.

Lack of collaboration and formal referrals

All participants perceived a lack of collaboration and a communication problem between the addiction centres and GPs. On the one hand, the addiction centres expel patients who misbehave (and often lack stability in usage and treatment), and on the other hand, stable opiate users often remain in the addiction centres for substitution treatment.

There is no outflow, and that is a big concern for us. In the centre, the people get older. For us, it is as if they stay with us, they are on methadone, and we do not see the need for them to get off it and they do not want to either. But they could easily go to the GP for their methadone; it would be better for everyone and especially for them, but this does not seem possible. (FGD specialized centres)

As a result, the physicians from the specialized centres unwillingly took on the role of GP for these stable patients with co-morbidities. The GPs and the physicians from the addiction centres would prefer to have more collaboration to coordinate formal referrals to avoid this situation.

… That was not really the intention, was it? The problem is that for some of the patients we are primary health care providers. They come more and more for menopause, hypertension, INR follow up … (FGD addiction centres)

GPs feeling anxious

The GPs felt anxious about treating patients with addictions. They felt they could not manage these patients, because they often lie, misbehave or do not attend appointments.

What am I taking on if I start something like this? I feel completely lost when dealing with addictions. I’m not trained for this, it is not my thing, I can’t do it, and the anxiety is probably what puts me off even more, especially methadone which I think is one of the worst things… (GP without experience)

The GPs felt anxious about prescribing OST because by doing this, they are subject to strict monitoring by a supervising commission.

Yes, because you really don’t want to prescribe narcotics. You might have to justify yourself to the Order of Physicians because you prescribed them so often. I think that that really is part of it. (GP with experience)

Some expressed a fear of being stigmatized as a ‘GP who prescribes methadone’.

My biggest fear is that my name will become known, and instead of having one patient, they’ll bring along three friends. Moreover, that they will sit there in the waiting room, between all the small children running around, and then the parents will get angry. It may be a worst case scenario but it doesn’t seem so unlikely to me. (GP without experience)

Lack of knowledge about OST

GPs felt inadequately trained to treat opiate users. GPs needed specific expertise to be able to treat opiate users, which could only be obtained by treating more patients and/or in collaboration with an addiction centre.

Well, as I have already said; I think this should be done in a more organized setting. You have to be able to treat a lot of patients to build up some real expertise. (GP without experience)

GPs were not sure how to start OST, how to do the follow-up and what dosage could be prescribed. They preferred to have more counselling from the specialized centres or more experienced colleagues to support them in prescribing OST.

Although GPs expressed a lack of knowledge and training on the subject, they showed no willingness to participate in the information sessions offered by the addiction centres:

It was much too specialized; it was meant for people who already know this world. It was a bridge too far for me. Well, it was simply not designed for GPs, but for healthcare workers in the field and GPs who are already involved in this area. (GP without experience)

A system was suggested whereby a small group of ‘advisory physicians’ receive training on the subject and then in turn give their colleagues advice.

In fact, a system similar to the ones for other conditions (such as the end of life), with advisory physicians you can turn to when you need help. You could do that for addiction as well. Come on, it must surely be possible for this condition. (GP with experience)

Preferably regular and stable patients

Less experienced GPs mostly took on patients (or relatives of patients) who were already in their client database. Most of these patients were stabilized, working again and had a family life. Most non-experienced GPs refused unknown new addicted patients.

I knew M as a 16-year-old boy. He came back a few years ago with a request for methadone. I tried to put him off … but in the end, I did it anyway. A couple of years, or no, not so long after this, his girlfriend came to see me, and now I prescribe it for her as well. (GP with experience)

Additionally, the GPs reflect on the possible advantages of OST for patients when care is provided in the general practice instead of the addiction centres, which are safety, privacy, no waiting lists, no stigma and being able to deal with the co-morbidities of the patient. The main disadvantage is the consultation fee that patients need to pay at the GP.

An advantage, yes, the dealers hang around [the addiction centres, red.] and, I mean, that is an advantage for the general practice, I find. The threshold is relatively low, the payment is a different problem, but it is mostly more anonymous and safer for the patient when they do not have to stand in line at the addiction centres. (GP with experience)

Need for emergency care

GPs express criticism about the lack of collaboration in case of emergency. The addiction centres are only open during office hours and have no 24/7 accessibility. During evening hours and weekends, patients need to go to emergency departments and the out-of-hours GP service. If the patients need to be hospitalized, the situation can become dramatic because often there is no room for drug addicts in the intensive care unit.

And let’s not to make it more difficult for the patients, because the moment it goes wrong and they have to wait one or two weeks before they can be seen, I think that will make the problem much worse, and they will start looking for drugs or taking heroin again. (Focus group addiction centres)

In some cases, this means that GPs do not have any support when the patient is in crisis. The GPs suggest foreseeing a telephone number to call in a case of emergency.

Discussion

Main findings

When studying the experiences of opiate substitution treatment in general practices, several barriers were encountered. There is a lack of communication and collaboration between the GPs and the addiction centres concerning the referrals or follow-up of OST for opiate users. The current engagement of GPs in OST does not meet the large demand for referral expressed by the addiction centres; however, there would appear to be more potential for collaboration within the GPs than is now the case. GPs’ willingness to engage in OST is low in the current study. The illegal nature of the substances and the specific characteristics of the patients who come for OST hold the GPs back. The lack of knowledge of GPs about OST creates anxiety and insecurity. Also, a shortage of support from the addiction centres negatively influenced the attitude of GPs towards OST. However, the GPs do see relevant advantages for patients to receive OST in the general practice, regarding safety, privacy, stigmatization and the ability to manage the co-morbidities in the patient. The feeling of being alone and having no support in case of emergencies was a barrier that was not found as explicitly in previous studies and should be addressed on a local level.

Limitations of the study

Although the number of participants in this study may seem small, and the exact number of Belgian GPs who prescribe OST is unknown, we can assume that we reached almost all of the GPs who prescribe OST in the Antwerp region (based on snowball sampling). This resonates with results from other countries where the number of GPs providing OST falls far below the demand.[Citation19]

The current study was conducted in 2009. However, we believe this data still holds an important value for the illegal drug services. First, the outflow of opiate users from addiction centres to general practices remains low in Antwerp,[Citation16] compared to Australia and Switzerland for example, where most of the opiate users go to the GP for treatment.[Citation11,Citation30] Second, Belgian regulations regarding OST remain unchanged up until now, so the hurdles and barriers experienced by GPs remain relevant. This is confirmed in a recent study by Ketterer et al., where personal attitudes and motivation were the main hurdles for managing substance abusers.[Citation26]

Interpretation of the study results

Since 2002, Belgian physicians can legally prescribe opiate substitutes for the treatment of addiction.[Citation18] This study shows that, although this regulation permits physicians to treat opiate users, the strict regulatory conditions seem to inhibit them from doing so. Additionally, the practical application of these regulations is not always clearly stated. The GPs’ fear of facing possible prosecution keeps them from engaging in OST.

Although the study was performed in a local context, it seems to echo the findings of other European studies. First, the anxiety in GPs was the main factor to withhold them from accepting opiate users in their practice.[Citation9,Citation28,Citation29] Second, the need for more support (hands-on guidelines and information) for treating these patients, which also confirms previous research in the UK.[Citation9,Citation27,Citation29] Clarification of the practical implications of the regulatory conditions is needed to increase the willingness of GPs to engage in OST. Previous research has pointed out that the willingness of GPs to treat opiate users depends on the attitude, behaviour and the motivation of the patients towards the treatment.[Citation27,Citation28]

Our study discussed some relevant advantages for patients to receive OST in general practice instead of in the addiction centres. Since these are only a few results, further research is needed to know what patients’ experiences are regarding OST in general practice.

Although international guidelines exist on substitution treatment for opiate users (pharmacological and medical management of OST), it remains difficult to assess the right treatment for every individual patient.[Citation22,Citation30] The availability of workshops that discuss hands-on guidelines for methadone substitution with clear targets could help doctors prescribe OST in general practice.

The biggest barrier is perhaps the growing pressure on the declining workforce of GPs in Belgium, which leaves little room for taking on additional tasks such as OST.[Citation31]

Implications for policy

The anxiety in GPs for dealing with these types of patients creates a reluctance to learn more about OST training. Longman et al. have also observed a high amount of GPs declining to attend training on OST prescribing and, therefore, call for action to address the barriers GPs face.[Citation32] Previous studies have made some suggestions to overcome the reluctance in GPs to attend training are discussion groups on practical cases, community based nurse prescribing, and multidisciplinary collaboration.[Citation11,Citation26,Citation33] From our results rose the idea of ‘advisory physicians’, GPs who are trained in OST management who provide advice to their colleague GPs whenever needed. This can be a timesaving solution and stimulate sharing of knowledge and experience amongst colleagues.

Conclusion

Overcoming anxiety in GPs to treat opiate users, increasing the knowledge of OST in GPs and improving the collaboration between GPs and addiction centres seem to be the most important challenges to be addressed to increase the acceptance of OST in general practice.

Acknowledgements

The Antwerp council for drug-related affairs (Stedelijk Overleg Drugs Antwerpen- SODA) financially supported the current study. Additionally, the authors thank all the physicians who participated in the interviews for the study.

The Ethical Committee of the University Hospital of Antwerp gave permission for this research project (B30020095443;02/02/09).

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- NICE. Drug misuse. Opioid detoxification. National clinical practice guideline number 52. London: National Collaboration Centre for Mental Health, 2008.

- Simoens S, Matheson C, Bond C, et al. The effectiveness of community maintenance with methadone or buprenorphine for treating opiate dependence. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:139–146.

- Pelc I, Casselman J, Bergeret I, Corten P, et al. Substitutiebehandeling in België. Ontwikkelen van een model ter evaluatie van de verschillende types van voorzieningen en van de patiënten. Leuven: KU Leuven, 2003.

- Keen J, Oliver P, Mathers N. Methadone maintenance treatment can be provided in a primary care setting without increasing methadone-related mortality: The Sheffield experience 1997–2000. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:387–389.

- Keen J, Rowse G, Mathers N, et al. Can methadone maintenance for heroin-dependent patients retained in general practice reduce criminal conviction rates and time spent in prison? Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:48–49.

- Keen J, Oliver P, Rowse G, et al. Does methadone maintenance treatment based on the new national guidelines work in a primary care setting? Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:461–467.

- Strang J, Hall W, Hickman M, et al. Impact of supervision of methadone consumption on deaths related to methadone overdose (1993–2008): Analyses using OD4 index in England and Scotland. Br Med J. 2010;341:c4851.

- Strang J, Sheridan J, Hunt C, et al. The prescribing of methadone and other opioids to addicts: National survey of GPs in England and Wales. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:444–451.

- Matheson C, Pitcairn J, Bond CM, et al. General practice management of illicit drug users in Scotland: A national survey. Addiction. 2003;98:119–126.

- Matheson C, Porteous T, van Teijlingen E, et al. Management of drug misuse: An 8-year follow-up survey of Scottish GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:517–520.

- Pelet A, Besson J, Pecoud A, et al. Difficulties associated with outpatient management of drug abusers by general practitioners. A cross-sectional survey of general practitioners with and without methadone patients in Switzerland. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:51.

- Drug treatment overview for Belgium Lisbon [Internet]. Belguim: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA); 2015 [cited 2015 Sep 24]. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/data/treatment-overviews/Belgium

- Tieberghien J, Decorte T. Antwerpse Drug- en Alcoholmonitor. Een lokale drugscene in beeld. Leuven/Voorburg: Acco; 2008.

- Ort C, van Nuijs AL, Berset JD, et al. Spatial differences and temporal changes in illicit drug use in Europe quantified by wastewater analysis. Addiction. 2014.

- SODA. Antwerp drug policy plan 2009–2012. Antwerp: Stedelijk Overleg Drugs Antwerpen, 2013.

- Annual Report 2013. Antwerp, Belgium: Free Clinic vzw, 2014.

- DH. Drug misuse and dependence. UK guidelines on clinical management. London: Department of Health (England), the Scottish Government, Welsh Assembly Government and Northern Ireland Executive, 2007.

- Federale overheidsdienst volksgezondheid, veiligheid van de voedselketen en leefmilieu. Koninklijk besluit tot wijziging van het koninklijk besluit van 19 maart 2004 tot reglementering van de behandeling met vervangingsmiddelen. 6 oktober 2006, publicatie Belgisch Staatsblad: 21/11/2006.

- Longman C, Lintzeris N, Temple-Smith M, et al. Methadone and buprenorphine prescribing patterns of Victorian general practitioners: Their first 5 years after authorisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30:355–359.

- Schulte B, Schmidt CS, Kuhnigk O, et al. Structural barriers in the context of opiate substitution treatment in Germany—a survey among physicians in primary care. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013;8:26.

- Scarborough J, Eliott J, Braunack-Mayer A. Opioid substitution therapy—a study of GP participation in prescribing. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:241–5.

- Pelc I. Advice from the High Council of Health. Advice concerning substitution treatment in opiate users. Brussels: High Council of Health; 2006.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Cornwall: SAGE Publications; 2006. p. 208.

- Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE guide no. 70. Med Teach. 2012;34:850–861.

- Fraeyman J, Anthierens S, Peremans L, et al. Het gebruik van diagrammen tijdens de data-analyse. KWALON. 2014;19:83–91.

- Ketterer F, Symons L, Lambrechts MC, et al. What factors determine Belgian general practitioners’ approaches to detecting and managing substance abuse? A qualitative study based on the I-Change Model. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:119.

- Langton D, Hickey A, Bury G, et al. Methadone maintenance in general practice: Impact on staff attitudes. Ir J Med Sci. 2000;169:133–136.

- McKeown A, Matheson C, Bond C. A qualitative study of GPs attitudes to drug misusers and drug misuse services in primary care. Fam Pract. 2003;20:120–125.

- McGillion J, Wanigaratne S, Feinmann C, et al. GPs attitudes towards treatment of drug misusers. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:385–386.

- Frei M. Opioid dependence—management in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39:548–52.

- Roberfroid D, Stordeur S, Camberlin C, et al. Het aanbod van artsen in België: huidige toestand en uitdagingen. Health Services Research (HSR). Brussel: Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de Gezondheidszorg (KCE); 2008.

- Longman C, Temple-Smith M, Gilchrist G, et al. Temple-Smith M, Gilchrist G, et al. Reluctant to train, reluctant to prescribe: Barriers to general practitioner prescribing of opioid substitution therapy. Aust J Prim Health. 2012;18:346–51.

- Van Hout M-C, Bingham T. A qualitative study of prescribing doctor experiences of methadone maintenance treatment. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2014;12:227–242.