Abstract

Background

Peer-assisted learning (PAL) is used throughout all levels of healthcare education. Lack of formalised agreement on different PAL programmes may confuse the literature. Given the increasing interest in PAL as an education philosophy, the terms need clarification. The aim of this review is to 1) describe different PAL programmes, 2) clarify the terminology surrounding PAL, and 3) propose a simple pragmatic way of defining PAL programmes based on their design.

Methods

A review of current PAL programmes within the healthcare setting was conducted. Each programme was scrutinised based on two aspects: the relationship between student and teacher, and the student to teacher ratio. The studies were then shown to fit exclusively into the novel proposed classification.

Results

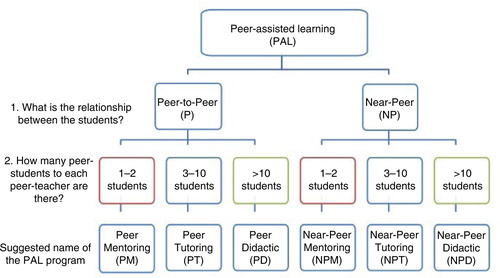

The 34 programmes found, demonstrate a wide variety in terms used. We established six terms, which exclusively applied to the programmes. The relationship between student and teacher was categorised as peer-to-peer or near-peer. The student to teacher ratio suited three groupings, named intuitively ‘Mentoring’ (1:1 or 1:2), ‘Tutoring’ (1:3–10), and ‘Didactic’ (1:>10). From this, six novel terms – all under the heading of PAL – are suggested: ‘Peer Mentoring’, ‘Peer Tutoring’, ‘Peer Didactic’, ‘Near-Peer Mentoring’, ‘Near-Peer Tutoring’, and ‘Near-Peer Didactic’.

Conclusions

We suggest herein a simple pragmatic terminology to overcome ambiguous terminology. Academically, clear terms will allow effective and efficient research, ensuring furthering of the educational philosophy.

Peer-assisted learning (PAL) as an educational method has been around since Socrates and Plato began questioning one another's ideas in small groups (Citation1). In recent times, PAL has gained increasing attention across many different healthcare disciplines and educational sectors (Citation1). Naturally following such is a growing body of evidence to determine its usefulness.

The benefits of PAL has been well-described by Topping et al. (Citation1) and clearly pertain to all stakeholders (i.e., the universities, the peer-teacher, and the peer-learner) (Citation1–Citation3). There appears to be a climate of readiness to formally incorporate PAL into different areas of healthcare studies.

PAL has one philosophy: students learning from students (Citation4). Two different relationships between the students and some variations in the arrangement of PAL programmes have carved out the different methods described to date. Given the simple and common root that all PAL programmes stem from, the extensively varying terminologies used is peculiar. Several mismatched terms exist throughout the literature. Examples of these include, but are not limited to: peer-led teaching, peer-led training, peer-tutoring, peer-teaching, collaborative learning, collaborative tutoring, cooperative learning, supplementary instruction, tutor-less group, peer supported learning, shared learning, co-teaching, co-tutoring, student partnership, facilitated peer mentoring, and similar variations of near-peer or cross year. The most commonly used term – peer-assisted learning – is arguably just an umbrella term encompassing all PAL programmes, and as such this term is non-descriptive (Citation1).

PAL has been extensively researched in the pedagogy (Citation5) and seems to carry less confusion about the terminology than in andragogy. This may be because adult learners are more heterogeneous than the young, as well as the environment in which they learn differs. The variance also appears in the preferred learning methods and the personal motivation (Citation6). Adult learners’ ‘richest resources for learning reside in the adult learners themselves’ (Citation6) (p. 45). Focus on experience-based techniques, including PAL, is therefore beneficial.

Terms need to be consistent for a number of reasons. Firstly, programme implementation is facilitated chiefly by clear terminology, communication, and intent. Secondly, for research purposes building an evidence-based foundation is more achievable. The uncertainty and incongruence around the terms weakens and confuses the research starting point. Thirdly, communication across institutions and disciplines is eased through accurate and consistent terms.

Attempts to clarify the terminology exist. Ladyshewsky (Citation7) outlined different PAL methods and suggested groupings based on common ‘indices’. Ten Cate and Durning (Citation8) designed a framework distinguishing between three elements.

Ladyshewsky (Citation7) argues there are two common indices that can describe all methods of implementing PAL – namely, 1) equality (e.g., to which extent learners take direction from each other) and 2) mutuality (e.g., in relation to the learners’ discourse). Although this may be theoretically sound, its applicability is limited by the non-practical definitions. Moreover, a single PAL programme may be difficult to define within the suggested category, as the indices are not quantifiable as well as overlapping.

Ten Cate and Durning (Citation8) on the other hand distinguish PAL programmes based on three believed core components: 1) education distance, 2) group size, and 3) formality. The distance is undoubtedly a key factor to consider and should differentiate between peers and near-peers. Further, the size of the group is also important as it has practical implications for the educational providers and correlates with students’ preferences and learning (Citation9). There is limited evidence around the impact formality has on the PAL outcomes. Furthermore, this is difficult to include in nomenclature given the spectrum formal involvement lies on and its vast variation amongst different education institutions.

Despite these clarifying attempts, inconsistencies continue to exist throughout the literature. This may be because the suggested components are difficult to define. We therefore aim to 1) describe the different methods in which PAL programmes have been incorporated to date, 2) clarify the terminology surrounding PAL, and 3) propose a simple pragmatic way of defining PAL programmes.

Methods

We searched five databases (PubMed, Cinahl, Medline, Proquest, and Embase) and two grey literature websites (www.greylit.org and www.tripdatabase.com), in a scoping review manner for articles of relevance (Citation10). The articles were narrowed down based on the key concepts of describing the implementation of a PAL programme and pertaining to the healthcare education. We included studies describing different forms of PAL in order to i) show the wide and varied approach PAL can take, and ii) to ensure that our suggested novel terms would be applicable to all methods of PAL practice.

We derived the new terms from a consensus process stemming from the different PAL methodologies within the literature. In accordance with previous nomenclature clarification attempts within other fields, we desired to keep well-established acronyms where possible, whilst also clarifying any confusion through making the novel terms more accurate in their description (Citation11).

Results

We describe 34 different approaches to PAL. From the findings, a clear disparity in nomenclature was determined, further highlighting the importance of formalising the terminology around PAL. The 34 programmes reviewed are listed in . Their methods and used terminology are tabulated.

Table 1 An overview of different PAL programs, their method and used terminology, presented sequentially based on the novel terminology

Given the wide variety, we propose a new pragmatic indexing approach, which is based on unambiguous components. Based on components commonly used to describe the programmes, we propose the new classification relates to the relationship between the students and the ratio of students to student-facilitators ().

Discussion

The umbrella term: PAL

PAL is the umbrella term and encompasses all programmes in which students learn from students, and does not specify any more than that. There seems to be confusion in the literature between PAL as an umbrella term and peer-to-peer learning. Peer-to-peer is the appropriate name when the students are peers; as opposed to near-peers. Considering that both students (i.e., the teacher and the one being taught) are learning and benefitting (Citation3, Citation4) may alleviate the confusion. Thus, the term peer-learner should not solely describe the student – which it often does – but rather describe both the teacher and student. We do not wish to alter this terminology because the acronym PAL is widely known and utilised.

Relationship between students: peer or near-peer

We consider peer and near-peer the first key separation because cognitive congruence is a vital component of learning (Citation8).

Our proposed classification therefore immediately begs the question – what is a peer? Is a peer merely someone at the same academic year level, or is it more appropriate to distinguish based on ability? Whilst disagreement on this question flourishes in the literature, Ladyshewsky (Citation7) and King (Citation46) concludes that without pairing students’ status and ability, the programme becomes simply tutoring, not peer-tutoring. The role of the faculty will be in facilitating and monitoring the relationship between their students.

The definition of a near-peer is generally clearer, and consists of two participants that are at least one academic year apart. However, exceptions exist. For instance, when PAL is used within interdisciplinary programmes, (Citation47) students may have different abilities although being at the same academic year level. We suggest that cases of interdisciplinary PAL programmes should be referred to as near-peers when they are at the same acedemic year level.

Ratio of students: mentoring, tutoring, or didactic

In concordance with Ten Cate and Durning (Citation8), we also consider the number of students in the group crucial. This correlates with students’ preferences (Citation9), thereby affecting the likelihood of engagement and implicitly learning. Ten Cate and Durning (Citation8) split the size of the PAL group into only two groups (i.e., 1 to <3 students, and 1 to ≥3 students). Given the varying dynamic of different group size, this distinction may be too blunt. We therefore propose a three-way split which is more consistent with traditional academic structuring, namely mentoring, tutoring, and didactic.

We define a programme as a mentor programme if the teacher to student's ratio is 1:1 or 1:2 (i.e., a microenvironment). Mentoring involves positive role modelling and reinforcement, supplemented by counselling, often used for disadvantaged groups (Citation3). PAL by mentoring is beneficial in that it provides a more intimate setting where students are more inclined to ask questions and express uncertainties. Furthermore, the likelihood of student involvement in the process and direct monitoring of student progress by the teacher can be easily facilitated. The obvious drawback of PAL mentoring lies in resource demand. Finding compatible pairs is a challenge for the institution.

We define a tutorial as a setting where there is one teacher to between 3 and 10 students. Tutoring is often highly focused on curricula content and is characterised by the assignment of specific roles (i.e., tutor and tutee), most often with clear guidance around the structure (Citation3). The benefits of peer-tutoring are i) less resource demanding, ii) increased possibility for the university to follow up their peer-teachers, and iii) raised and diversified collaboration given the larger group and the inherent broader range of views and perceptions. However, this also leads to the possible drawback that quiet students may remain quiet and unnoticed, thereby limiting the utility of such a PAL programme for those students.

We define a programme as didactic if the teacher to student's ratio is in excess of 1:10. Among the vast array of learning methods and styles, although less common in PAL, is a class delivered lecture format. This one directional method is beneficial in that it uses minimal resources and teaches the peer-teacher to both prepare and present in front of a large group. However, limited possibilities for feedback, participation, and student interaction are considerable drawbacks to this method.

Based on the above-described components, every PAL programme will fall, mutually exclusively, under any of six categories. outlines these categories and illustrate their corresponding suggested names.

Conclusion

We have herein tabulated the main variations in PAL programmes and proposed a novel nomenclature classification. We are not classifying previous authors and their terminology as wrong, nor do we wish to correct them. We merely encourage future research in this field to be more consistent with its terminology. This will better enable the formal integration of PAL into educational programmes. To overcome the shortcomings of previous attempts at clarifying the terminology, we have proposed a clear, intuitive, and unambiguous nomenclature in which programmes mutually exclusively belong to just one term.

To broaden the platform of research around PAL and to allow easy integration across institutions, consistent terms and definitions are necessary. We urge consistent use of the PAL terms based on the suggested groupings offered in this paper. Expansion of the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms is necessary. It may be anticipated that new terminology introduction may be inconvenient at first, and it is unlikely that a consensus will be reached quickly; however, we believe the long-term benefits uniform terminology has on research and education outweigh this hindrance.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors.

Conflicts of interest and funding

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Topping KJ, Ehly SW. Peer-assisted learning. 1998; xviii Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates. 371.

- Hill E, Liuzzi F, Giles J. Peer-assisted learning from three perspectives: student, tutor and co-ordinator. Clin Teach. 2010; 7: 244–6.

- Topping KJ. Trends in peer learning. Educ Psychol. 2005; 25: 631–45.

- Boud D, Boud D, Cohen R, Sampson J. Introduction: making the move to peer learning. Peer learning in higher education: learning from and with each other. 2001, 1–17; London: Kogan Page. editor.

- Rohrbeck CA, Ginsburg-Block MD, Fantuzzo JW, Miller TR. Peer-assisted learning interventions with elementary school students: a meta-analytic review. J Educ Psychol. 2003; 95: 240–57.

- Knowles M, Swanson R, Holton EI. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. 2005; 6th ed, California: Elsevier Science and Technology Books.

- Ladyshewsky RK. Peer-assisted learning in clinical education: a review of terms and learning principles. J Phys Ther Educ. 2000; 14: 15.

- Ten Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007; 29: 546–52.

- Kooloos JGM, Klaassen T, Vereijken M, Van Kuppeveld S, Bolhuis S, Vorstenbosch M. Collaborative group work: effects of group size and assignment structure on learning gain, student satisfaction and perceived participation. Med Teach. 2011; 33: 983–8.

- Williams B, Reddy P. Does peer-assisted learning improve academic performance? A scoping review. Nurse Educ Today. 2016; 42: 23–9.

- Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, etal. Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: the International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005; 7: 393–5.

- Higgins B. Relationship between retention and peer tutoring for at-risk students. J Nurs Educ. 2004; 43: 319.

- Patel J, Rosentsveyg J, Gabbur N, Marquez S. Clay modeling for pelvic anatomy review for third-year medical and physician assistant students. Obstet Gynecol. 2014; 123: 19S–20S.

- Walsh CM, Rose DN, Dubrowski A, Linq SC, Grierson LE, Backstein D, etal. Learning in the simulated setting: a comparison of expert-, peer-, and computer-assisted learning. Acad Med. 2011; 86(10 Suppl): S12–16.

- Beard JH, O'Sullivan P, Palmer BJ, Qiu M, Kim EH. Peer assisted learning in surgical skills laboratory training: a pilot study. Med Teach. 2012; 34: 957–9.

- Nnodim JO. A controlled trial of peer-teaching in practical gross anatomy. Clin Anat. 1997; 10: 112–17.

- Steele DJ, Medder JD, Turner P. A comparison of learning outcomes and attitudes in student-versus faculty-led problem-based learning: an experimental study. Med Educ. 2000; 34: 23–9.

- Kassab S, Abu-Hijleh MF, Al-Shboul Q, Hamdy H. Student-led tutorials in problem-based learning: educational outcomes and students’ perceptions. Med Teach. 2005; 27: 521–6.

- Peets AD, Coderre S, Wright B, Jenkins D, Burak K, Leskosky S, etal. Involvement in teaching improves learning in medical students: a randomized cross-over study. BMC Med Educ. 2009; 9: 55.

- Knobe M, Holschen M, Mooij SC, Sellei RM, Munker R, Antony P, etal. Knowledge transfer of spinal manipulation skills by student-teachers: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2012; 21: 992–8.

- Knobe M, Munker R, Sellei RM, Holschen M, Mooij SC, Schmidt-Rohlfing B, etal. Peer teaching: a randomised controlled trial using student-teachers to teach musculoskeletal ultrasound. Med Educ. 2010; 44: 148–55.

- Manzoor I. Peer assisted versus expert assisted learning: a comparison of effectiveness in terms of academic scores. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2014; 24: 825–9.

- Sprengel AD, Job L. Reducing student anxiety by using clinical peer mentoring with beginning nursing students. Nurse Educ. 2004; 29: 246–50.

- Blank WA, Blankenfeld H, Vogelmann R, Linde K, Schneider A. Can near-peer medical students effectively teach a new curriculum in physical examination?. BMC Med Educ. 2013; 13: 165.

- Nestel D, Kidd J. Peer assisted learning in patient-centred interviewing: the impact on student tutors. Med Teach. 2005; 27: 439–44.

- Tolsgaard MG, Gustafsson A, Rasmussen MB, Hoiby P, Muller CG, Ringsted C. Student teachers can be as good as associate professors in teaching clinical skills. Med Teach. 2007; 29: 553–7.

- Wong JG, Waldrep TD, Smith TG. Formal peer-teaching in medical school improves academic performance: the MUSC supplemental instructor program. Teach Learn Med. 2007; 19: 216–20.

- Sobral D. Peer tutoring and student outcomes in a problem-based course. Med Educ. 1994; 28: 284–9.

- Hughes TC, Jiwaji Z, Lally K, Lloyd-Lavery A, Lota A, Dale A, etal. Advanced Cardiac Resuscitation Evaluation (ACRE): a randomised single-blind controlled trial of peer-led vs. expert-led advanced resuscitation training. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2010; 18: 3.

- Haist SA, Wilson JF, Fosson SE, Brigham NL. Are fourth-year medical students effective teachers of the physical examination to first-year medical students?. J Gen Intern Med. 1997; 12: 177–81.

- Brannagan KB, Dellinger A, Thomas J, Mitchell D, Lewis-Trabeaux S, Dupre S. Impact of peer teaching on nursing students: perceptions of learning environment, self-efficacy, and knowledge. Nurse Educ Today. 2013; 33: 1440–7.

- Burke J, Fayaz S, Graham K, Matthew R, Field M. Peer-assisted learning in the acquisition of clinical skills: a supplementary approach to musculoskeletal system training. Med Teach. 2007; 29: 577–82.

- Graham K, Burke JM, Field M. Undergraduate rheumatology: can peer-assisted learning by medical students deliver equivalent training to that provided by specialist staff?. Rheumatology. 2008; 47: 652–5.

- Graziano SC. Randomized surgical training for medical students: resident versus peer-led teaching. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 204: 542.e1–4.

- Perkins GD, Hulme J, Bion JF. Peer-led resuscitation training for healthcare students: a randomised controlled study. Intensive Care Med. 2002; 28: 698–700.

- Evans DJ, Cuffe T. Near-peer teaching in anatomy: an approach for deeper learning. Anat Sci Educ. 2009; 2: 227–33.

- Weyrich P, Celebi N, Schrauth M, Möltner A, Lammerding-Köppel M, Nikendei C. Peer-assisted versus faculty staff-led skills laboratory training: a randomised controlled trial. Med Educ. 2009; 43: 113–20.

- Kam JK, Tai J, Mitchell RD, Halley E, Vance S. A vertical study programme for medical students: peer-assisted learning in practice. Med Teach. 2013; 35: e943–5.

- Heckmann JG, Dutsch M, Rauch C, Lang C, Weih M, Schwab S. Effects of peer-assisted training during the neurology clerkship: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Neurol. 2008; 15: 1365–70.

- Blatt B, Greenberg L. A multi-level assessment of a program to teach medical students to teach. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2007; 12: 7–18.

- Batchelder AJ, Rodrigues CM, Lin LY, Hickey PM, Johnson C, Elias JE. The role of students as teachers: four years’ experience of a large-scale, peer-led programme. Med Teach. 2010; 32: 547–51.

- Field M, Burke JM, McAllister D, Lloyd DM. Peer-assisted learning: a novel approach to clinical skills learning for medical students. Med Educ. 2007; 41: 411–18.

- Hudson JN, Tonkin AL. Clinical skills education: outcomes of relationships between junior medical students, senior peers and simulated patients. Med Educ. 2008; 42: 901–8.

- Rengier F, Rauch PJ, Partovi S, Kirsch J, Nawrotzki R. A three-day anatomy revision course taught by senior peers effectively prepares junior students for their national anatomy exam. Ann Anat. 2010; 192: 396–9.

- Williams B, Olaussen A, Peterson EL. Peer-assisted teaching: an interventional study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2015; 15: 293–8.

- King A. ASK to THINK-TEL WHY: a model of transactive peer tutoring for scaffolding higher level complex learning. Educ Psychol. 1997; 32: 221–35.

- Saunders C, Smith A, Watson H, Nimmo A, Morrison M, Fawcett T, etal. The experience of interdisciplinary peer-assisted learning (PAL). Clin Teach. 2012; 9: 398–402.