ABSTRACT

Informal client contact forms a crucial part of the daily routine of service professionals, in particular among top-ranking professionals working for consultancy and accountancy firms. In this paper, we investigate how 34 service professionals develop informal client contact, by studying their networking styles. Our study shows many similarities in informal client contact between two groups of service professionals grouped by gender, but we also found subtle differences in what we coin instrumental and expressive relations. Contrary to gender stereotypes, we found that female service professionals tended toward instrumental networking styles, using professionalism and distance and allowing the high quality of their work compensate for network deficits, contingent upon their clients’ gender. Male service professionals drew on expressive relations to develop emotional bonding with their male clients in particular, but nonetheless toward instrumental purposes. Our study contributes to service industries literature by theoretically and empirically establishing the different informal networking styles between top-ranking service professionals, and the role of emotional bonding in particular. In doing so, the paper helps to better understand the intricacies of informal client contact as a critical dimension of the professional services industry.

Introduction

Pressures on professional service professionals to acquire and maintain service contracts has increased over recent years, while potential clients have become increasingly reserved in procuring professional services. These changes derive among others from increasingly strict regulation of ongoing service contracts, and formalization of service product procurement processes (Taminiau, Citation2013). Moreover, potential clients’ qualifications often match those of the consultants whom they turn to for advice. Indeed, potential clients are sometimes better equipped to solve problems themselves, through their own vast repertoire of in-house knowledge (Höner & Mohe, Citation2009; Sturdy, Citation2011). Moreover, in response to the financial crisis, corporate budgets for advisory services have been shrinking. One way by which professional service providers seek to counteract these developments is by investing in informal client relationships.

Informal client relationships comprise the personal contact between consultants and clients, which can facilitate balanced, trust-based interaction, and a smoother exchange of information (Czarniawska & Mazza, Citation2003; Levin & Cross, Citation2004). Informality is described as ‘casual, spontaneous, rather impromptu forms of social interaction and behavior’ (Morand, Citation1995, p. 831), in contrast to formality, which is seen as: ‘more rigid and deliberate, impersonal conduct, as well as environments that encourage such conduct’ (Morand, Citation1995, p. 831). Although the term ‘informal relationships’ is regularly used to indicate friendly relations, Morand (Citation1995) argues that contrary to friendship, informal contact can well be associated with professional aims. Behavioral informality can be instrumental in creating more organic, innovative organizations in which knowledge is shared easily (Morand, Citation1995), and can strengthen the emotional bonding between professionals and clients and contributing to shared values that form the basis for a successful relationship (Mohe, Citation2008).

Engaging in informal client relationships can help to strengthen service providers’ competitive advantage (Awazu, Citation2004), provided that the service provider possesses adequate interpersonal skills. In an effort to respond more competitively to client demands, service professionals are seeking to elevate their level of expertise and to enhance their interpersonal skills (Nikolova, Reihlen, & Schlapfner, Citation2009). These efforts are often manifested in the establishment of informal client relationships, aimed toward creating a mutual bond of trust with existing and potential clients (Taminiau, Citation2013). In this paper, we explore the different informal client interactions that male and female service professionals develop. We are interested in the similarities and differences in their efforts to establish and maintain informal client contacts.

Prior literature has identified several drivers of informal client relationships adopted by service professionals, in particular aimed at forging trusted relations and developing an emotional bond in support of acquiring long-term service contracts (Appelbaum & Steed, Citation2005; Glückler & Armbrüster, Citation2003; Kitay & Wright, Citation2004; Nikolova, Mollering, & Reihlen, Citation2015). However, studies have also established that the development of informal client contact is addressed differently among male versus female service providers, for instance, in terms of their networking styles and the prioritization of professional content versus socially oriented efforts (Anderson-Gough, Grey, & Robson, Citation2005; Dambrin & Lambert, Citation2012). Building on this strand of research and drawing on Ibarra (Citation1992), we distinguish two types of networking styles: expressive networking and instrumental networking. The first form is geared toward social and emotional support, while the latter relates to work-related networking aimed at realizing a person’s ambition and aims. In this paper, we explore these differences in networking styles toward developing informal client contact, guided by the research question: How do top-ranking service professionals apply expressive and instrumental means to develop client relationships? In doing so, we also explain how these different networking styles are manifested, heeding particular attention to whether established gender differences apply in terms of their emotional bonding among top-ranking service professionals, and among their clients.

Our insights contribute to literature in several ways. First, we provide a more fine-grained view of informal client relationship development in the service professional in general, and the role of emotional bonding therein in particular. Second, we provide more theoretical nuance of client relationship development, showing how prevailing gender stereotypes of informal client contact prove incompatible with the practice of service professionals. More specifically, we show how service top-ranking professionals adapt their choice of informal encounters to social role expectations, in which the gender of the parties involved plays a determining role. Besides these theoretical contributions, our study is also of use toward supporting practitioners in more consciously adopting a networking style that is beneficial for establishing and maintaining informal client contacts. We now introduce the theoretical framework guiding our study, before moving on to our empirical study and analysis.

Theoretical framework

Research on professionals in the service industry has recently shown a growing interest in the importance of informal relationships as a strategic tool to strengthen client loyalty (Karantinou & Hogg, Citation2010). One of the ways to professionally engage with clients is by developing a close, emotionally charged relationship (Kiely, Citation2005) as a way to strengthen the development of common ground between business partners in terms of, for instance, hobbies, convictions, and norms (Stalnaker, Citation2002). However, with increased competition, institutional pressures and changing procurement regulations in the advisory and audit sectors (Taminiau, Citation2013), service industries are facing new, challenging questions. These questions relate to the possibilities or impossibilities of informal client relationship development, and to the institutionalization of informal practices within the service industry (Taminiau, Citation2013).

In parallel, gender-related questions, for instance, related to differences in networking styles, are becoming more pronounced. This might be catalyzed by a growing group of top-ranking females permeating various service industries (Sealy & Vinnicombe, Citation2012), generating more heterogeneous working environments, and evoking questions of how and whether industries need to heed attention to gender differences. To address this issue, we combine two strands of literature. First, we look into the literature on informal client relationship development in the service industries, particularly focusing on the use of emotional bonding between business partners. Second, we draw on literature related to informal networking styles, extending seminal work by Ibarra (Citation1992; Citation1997) and more recently, Ding, Murray, and Stuart (Citation2013). So doing, we further our understanding of how service professionals engage in informal networking styles particularly by seeking to establish emotional bonds, critically examining established gender differences therein among professionals, and among their clients.

Informal client relationship development and the importance of emotional bonding

Professional relationships between consultants and their clients tend to incrementally evolve from impersonal, content-oriented relationships into more personal and equivalent relationships. Indeed, an interpersonal ‘fit’ between the consultant and the client is considered a critical success factor in service provision (Fullerton & West, Citation1996, p. 41). Such a ‘fit’ is underpinned by trust, cooperation and informal interaction (Nikolova et al., Citation2009; Sturdy, Schwarz, & Spicer, Citation2006). The art of creating an interpersonal fit has become more important, as consultants have to make more effort to retain their clients, due to increasingly competitive environments (Nikolova et al., Citation2009). Recently, this shift has become even more pronounced: with many firms all offering similar high-quality services in a shrinking and sharply regulated market, social interaction emerges as a competitive distinction.

The strategic use of social interaction, geared toward developing informal relationships, is common within the professional service industry such as consultancy and auditing, as a way to exchange different kinds of information (work and non-work related). Informal relationships flourish best in settings away from the office, for instance, in the form of business lunches, cultural events or sporting activities (such as golf). Such settings do not replace formal work settings and/or relationships. Instead, the two settings operate in parallel to each other, allowing for more personal and intimate conversation (Morand, Citation1995) and potentially leading to a better understanding of the character and deeper emotional configuration of business partners. For example, the way in which business partners engage in a competitive game can be informative (Ceron-Anaya, Citation2010; Kaiser, Müller-Seitz, & Creusen, Citation2008), revealing how a person copes with losing, or whether he/she is a fair player. Moreover, spending time together during a game or dinner can contribute to developing common interests and a feeling of bonding, or understanding one another at a deeper level (Arnould & Price, Citation1993; Stalnaker, Citation2002).

Studies of the consultancy sector, for instance, have shown that most consultancy assignments are awarded to service professionals with whom the client has shared good, personal experiences in the past (Glückler & Armbrüster, Citation2003). Clearly, the stronger the client–consultant relationship, the less chance there is that the client will seek out a competitor (Appelbaum & Steed, Citation2005; Johnson & Selnes, Citation2004). An emotional connection with the business partner is therefore essential, and indeed, numerous authors have established state that trust – the basis of a positive emotional bond – is the most important aspect of cooperation between business partners (Armbrüster, Citation2006; Hislop, Citation2002; Kipping & Engwall, Citation2002; Taminiau, Berghman, & Den Besten, Citation2013). In summary, the development of strong and trusted informal relationships between service professionals and clients is a complicated and subtle process; yet, once established and adequately maintained, these relationships can be instrumental to the generation of business. However, as the service industry becomes increasingly diversified (O’Mahoney & Markham, Citation2013), it is important to examine how different professionals go about informal relationship development. Indeed, with a growing number of women permeating the upper levels of different service industries including consulting and accounting, it is inevitable that gender dimensions come to the fore, as we now explain.

Gender considerations in informal client relationship development

A growing body of literature has studied informal client relations from a gender perspective, as a means to explain how professionals adopt different strategies to attain their business goals. For instance, Anderson-Gough et al. (Citation2005), Metz and Tharenou (Citation2001) and Singh and Vinnicombe (Citation2001) suggest that informal social networks are vital for both men and women in order to succeed. However, the propensity toward developing informal networks seems to vary between female and male service professionals. Empirical findings seem to suggest that high-level male service professionals have ‘better’ informal networks at their disposal – comprising of stronger, and higher level peers and (potential) clients – and invest more time in client relationship development compared to their female counterparts, who often spend more time on developing the quality of their content (Anderson-Gough et al., Citation2005). In this way, a strong network of male professionals sometimes trumps higher quality service delivery provided by their female counterparts (Ciancanelli, Gallhofer, Humphrey, & Kirkham, Citation1990; Dambrin & Lambert, Citation2012).

Female professionals thus sometimes appear to be at a disadvantage in terms of capitalizing on networking opportunities, described as ‘capital and return deficits’ in their informal social networks (Lin, Citation2000). In a similar vein, Ibarra (Citation1992) describes how work-related networks differ between men and women, and what kind of benefits can be derived from these structures. Indeed, she showed how men in the advertising industry have a propensity to network primarily with other men, rather than with women. This preference is in accordance with the ‘homophily principle’ (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, Citation2001), and which comprises the preference toward ‘interaction with others who are similar given attributes such as sex, race, and education’ (Ibarra, Citation1992, p. 423). Moreover, Ibarra explains: ‘an attraction to similarity of personal characteristics implies common interests and worldviews’ (Ibarra, Citation1992, p. 423); in other words, the more similar people are, the more likely they are to have shared perspectives, and develop emotional bonds.

Since powerful and influential positions in business and in society are still most often occupied by men (McDonald, Lin, & Ao, Citation2009), this raises the question whether the male-predominant orientation among professionals derives from homophilious motives, or merely from strategic motives of seeking to network with a senior person. This issue remains difficult to untangle. In her seminal study of networking strategies among men versus women, Ibarra (Citation1992) distinguishes two types of networks. First, instrumental networks are primarily task-related, focused on access to strategic resources and advice. Second, expressive networks are used to share feelings and ideas/views with others. The study showed that men primarily tend to invest their time and effort in instrumental professional networks and mainly interact with men, and maintain a few expressive network relationships (social support and friendship) with their female peers. Expressive networks are akin to the previously described emotional bonding, commonly used by male service professionals in the development of external relations. Women tend to maintain more differentiated networks: for instrumental networking, they tend to direct their attention to their superiors, mostly men (higher status instrumental contacts), while focusing on their female peers as part of their expressive network (Ibarra, Citation1992). However, both groups make rational choices in favor of higher status instrumental contacts.

These differences in networking styles might place women at a disadvantageous position in terms of the resource and capital deficits described above. However, a dilemma for women may also lie in men’s reciprocation of their choices, in terms of both expressive and instrumental resources: ‘if network contacts are chosen according to similarity and/or status considerations, [women] are less desirable network choices for men on both counts’ (Ibarra, Citation1992, p. 440). In other words, women remain in a disadvantageous position because men are less likely to reciprocate their networking efforts, due to the lower (instrumental) incentives and rewards to do so.

In our study, we examine networking styles among top-ranking service professionals toward their clients (most often male), analyzing how differences between men and women are manifested toward instrumental goals of generating business opportunities; however, given the significance ascribed to emotional bonds in terms of realizing those opportunities, we also attend to expressive means, thereby analyzing how these different network styles play out for developing informal client relationships.

Setting and methods

In our study, we sought to understand how top-ranking service professionals apply expressive and instrumental means to develop client relationships. In responding to this question, we particularly attend to the way in which men and women apply different networking styles in terms of their emotional bonding. We started with a literature study in order to obtain central themes guiding our research in general and helping us to formulate appropriate questions to address our empirical study. We applied an inductive research approach, consisting of qualitative interviews complemented with a semantic content analysis of informants’ responses (as described by Williams & Shepherd, Citation2015). This approach is appropriate, as it allows for gathering perspectives from service professionals themselves on how they develop informal client relationships in practice (Eisenhardt, Citation1989); moreover, adding the semantic analysis helped to corroborate our interpretive findings, and revealed discourses that remained latent based on the qualitative methods alone (reference suppressed). In this manner, we were able to strengthen the rigor of our findings (as called for by Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Citation2013).

The dataset presented in this paper is part of a larger study comprising 250 interviews on different dimensions of informal client contacts in the consultancy and accountancy sector, across 11 Western countries.Footnote1 From this dataset, we selected all top-ranking females, at partner and senior management level, within large consultancy and accountancy firms, comprising 17 in total. We selected these informants as the most senior persons with professional service firms are often responsible for client relationship development, acquisition and sales, and they were therefore well positioned to provide us with elaborate material. In order to be able to compare and contrast their accounts, we then selected interviews with 17 top-ranking male partners and senior managers, generating the best possible match between female and male informants in terms of seniority, sector and country (see ).

Table 1. Overview of dataset.

The interviews were conducted by a team of nine research assistants, whereby each assistant collected the total dataset for a particular country, during the period early 2009 till mid-2010. The interview questions, which we operationalized from the central themes apparent in the literature, concerned the content of informal contact, the location, when contact takes place, hierarchal levels involved, purposes, the ‘dos’ and the ‘don’ts’. The interviews were conducted in English, lasted an average of sixty minutes, and all followed the same order of questions. All interviews were recorded and transcribed.

To safeguard the quality and consistency of the interviews, we used a semi-structured interview protocol, probing for additional details. For example, at the outset, we invited all the informants to ‘set the scene’ by listing types of informal engagements they pursued with their clients, and where necessary offering suggestions (such as drinks, lunches, sports activities, and small talk). We also asked how much time they approximately spent on informal client relationships, how they described the mix between personal and business affairs, the timing and location of these activities, and so forth. We also asked why our informants engaged in these activities, and whether this was incentivized from personal motives or as a result of organizational pressure or encouragement. By consistently asking these questions, while probing for additional information, we were able to generate comparable, yet detailed descriptions from the group of informants.

All interview transcripts were analyzed interpretively, organizing and reducing data in order to discover patterns (Miles & Huberman, Citation1994), using the qualitative software program Atlas.ti. First, relevant information was divided into fragments and labelled. These labels were then arranged and reduced, which led to key defining labels. In this way, it was possible to separate ‘code families’ and ‘text families’ corresponding to the different themes that we previously identified from the literature. The findings were discussed by the research team, clarifying codes and explanations where necessary, and comparing outcomes – both across different informants, and with existing literature – to seek overarching patterns.

Through this analytical process of empirical and theoretical comparison, we discovered different approaches to informal client contacts among the male and female service providers we spoke to, but these differences varied from what we expected based on the literature, particularly in terms of the role of emotions in the creation of trust. In a second round of coding, we therefore linked the descriptions of professionals’ development of informal client relations to first, instrumental motives, second, expressive motives and third, how gender plays out at the level of choices with regard to informal activities and encounters, as described by the different parties involved.

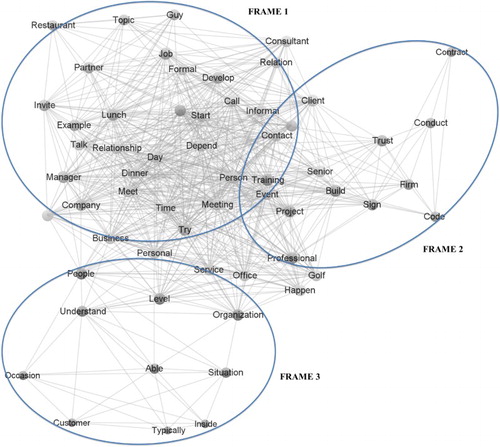

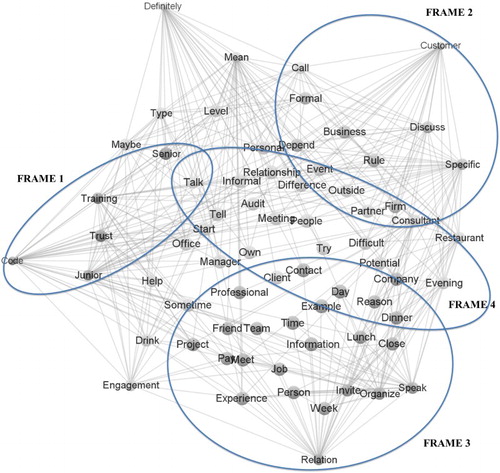

To corroborate the findings from our interpretive coding, we conducted a semantic network analysis based on the two datasets of female versus male top-ranking service professionals, derived from transcribed interviews. We used a tool for natural language processing (Leydesdorff & Welbers, Citation2011) to calculate the correlations between the most frequently used words in each of the datasets. We then conducted a factor analysis to identify word groups (included in ),Footnote2 visualizing the ensuing semantic networks by using Pajek (Batagelj & Mrvar, Citation2004) and VosViewer (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2009). This analysis provided useful insights into what our two groups of informants expressed most commonly in terms of their informal client contact, and helped to identify additional, sometimes subtle themes that remained latent in the qualitative interpretive analysis. These two analytical approaches helped us to strengthen the rigor of our findings, which we show below.

Table 2. Results factor analysis semantic network.

Findings

We identified two main differences in networking style between male and female top-ranking service professionals: instrumental and expressive differences. Instrumental differences refer to the activities, content and purpose of informal client contact. Expressive differences refer to the specific types of relationships which service professionals seek to generate with their clients. In addition, we also show how male and female informants perceived these differences in networking style in different ways.

Instrumental differences: activities, content and purpose of informal relationship development

When questioned about informal business-related activities, women often indicated that they preferred to engage in informal client contact during working hours, for instance, during lunchtime meetings, reserving the evenings for their families. Men had fewer objections to informal client contact outside working hours, favoring dinner meetings, sport events and even conducting business meetings at their own or their client’s home. Women also took their clients to sports events (such as football matches), but less regularly than men, and generally as part of an event organized by their firm. Several women expressed that they felt more or less obliged to attend such sports events, which they considered as instrumental, corporate-driven ways to develop client relationships. Indeed, the fact that obligatory corporate events were often sports-oriented reflects a stereotypically male-oriented activity, and indicates the level to which these women operated in a ‘man’s world’.

In terms of the content of informal client contact, the degree to which contact was informal or businesslike in nature showed some gender differences. Women preferred client contact that was more businesslike and content-oriented than men. At the same time, the female informants recognized the need to connect with their clients at a personal level. To strengthen this connection, some women focused on clients’ personal preferences, such as their favorite sport activities and leisure time, as one manager explained:

I try to remember what they like for sports, if they have a summerhouse somewhere, if they have kids, how many they have you know than next time you can ask questions related to those things and so sure. (f3)

Many emphasized the need to maintain professional boundaries, despite the informal appearance of certain business meetings:

I don’t mind meeting for lunch in a bar or go occasionally to a restaurant, but it has to stay professional and somewhere where business can also be done in a normal way. (…) We have some informal contacts of course, but it is better to keep it professional. I don’t like to mix that thing too much (…). (f17)

Overall, women thus maintained fairly strong professional boundaries, which was contrasted by their male counterparts. Fully aware of the instrumental character of their informal business engagements as a way to strengthen personal relationships, male professionals emphasized far more strongly the social dimensions, seeking out emotional bonding and forging expressive relationships: ‘When you are discussing a soccer game or the Tour of Flanders, what’s important is the social aspect. It’s mostly about doing something fun together.’ (m13)

In fact, explicit reference to business was often deemed inappropriate, at special events such as a ballet or opera: ‘Of course, we never speak about business during these kinds of events. We only talk about business indirectly, because it would be very, very rude to do otherwise.’ (m11), which was confirmed by this partner’s Canadian colleague as a means to strengthen their mutual trust: ‘If you are doing something for them that is non-business related, it makes them trust you more as a human than just a service provider.’ (m15)

The instrumental purpose of informal client contact was described first and foremost as a means to help them to achieve their goals, and they carefully considered when to utilize it:

It’s to have personal contact, to know each other better. Because it is easier to work with a person you know better. It is easier to speak about problems with somebody you know better. It is more difficult to understand each other if you don’t know each other well. (m9)

To enable this personal contact, men tended to make a greater effort to indulge their clients. Whereas a female senior manager emphasized convenience: ‘Normally I will meet them not very far from their office. […] And if I have absolutely no idea of a good restaurant […] I can ask him or her for a preference of restaurant’ (f12), it was not uncommon for male manager to go to quite some effort and expense: ‘You have to bring the client to a very good restaurant’ (m17).

However, they saw this as an investment, to be reciprocated at a later point in some form. Moreover, taking clients to exclusive venues appeared to be a way for male service professionals to emphasize the exclusivity of their organization’s network, which they were ‘inviting’ the potential client to become a part of:

This client felt that he was very important to our organization, because we invited him to a very VIP place. That also means that our organization must have important connections, to be able to have a table in such a VIP setting. (m10)

Overall, our analysis showed that female and male professionals showed subtle instrumental differences in their informal client contacts. However, they showed more pronounced expressive differences, in terms of their perceptions and usage of their informal networks, as we now show.

Expressive differences: types of relationships in informal client contact

We found that women and men equally valued informal client contact, anticipating a better business atmosphere, more trust and confidence, more successful transactions and more commitment to a particular business arrangement among business partners. Both considered relationship building to be one of the primary purposes of informal client contact, although women appeared to be even more aware of this purpose, singling it out more often than men. One female informant indicated, for example: ‘If there is no good relationship in place, you will not be able to acquire a lot of contracts either’ (f2). However, women sometimes preferred to draw on their existing networks, intensifying relationships as a possible business opportunity, but clearly also appreciating the expressive benefits, such as access to social support and friendship, often with a homophilious nature:

For me […] what I have done sometimes, […] I created, converted business relationships into personal relationships, you know, I made them informal. We have a professional women’s network, it started when I was a manager, and I started to participate in those events. What I did, I invited some, certain client contacts to events where they encourage you to bring the client for that purpose, to try to get to know them on a personal level. And when I started doing that with certain of my contacts, they really enjoyed it, we got to know each other on a personal level, it converted the relationship, almost it was less a business, more a personal relationship. (f5)

Gender differences in developing informal client relationships

Clearly, both men and women recognized that an expressive network and – more specifically – building a mutual bond of trust was a useful way to create new business opportunities, and comprised an essential part of relationship building. Nonetheless, the way in which men versus women perceived these relationships showed some surprising differences: women tended to keep their distance, separating work and private matters, whereas these boundaries were less clear among several male partners. Indeed, one male partner indicated: ‘( …) You need to develop an almost extremely interpersonal relationship; emotional even’ (m14), and ‘You really talk about private stuff, other things politics and so on’ (m4), which women were generally more reticent to do once a business relationship was established:

‘I prefer to keep a certain distance. It could be risky; we don’t know exactly what people think about these subjects. You have to be quite close to your client, but not too close’ (f9).

Indeed, although relationships often were considered pleasant, professional interests always remained at the forefront:

‘You can discuss about the business, but it is more general, for example about acquisitions, the market and after that you can speak about vacation and also after that going back to the business subjects’ (f9).

Overall, both male and female service professionals engaged in developing informal client relationships as a critical strategic activity, with subtle instrumental and expressive differences. However, expressive differences became more pronounced – and indeed often at a disadvantage for female service professionals – when women engaged in informal contacts with male counterparts. Namely, in line with Ibarra (Citation1992), some female service processionals indicated that, despite their senior ranking, their male counterparts often treated them in conformance with stereotypical role divisions. For instance:

It’s different if you are a female partner. Perhaps people are more, let’s say, polite. If you are a woman, a client is probably less likely to use coarse language than if faced with a male partner. But it’s also true that in some organizations it’s just very difficult for them to imagine that a partner could be a woman. (f9)

My current client tells me every time that women should stay at home if they have young children. He tells me: ‘what are you doing here, your child is still so small’. It’s hard for him to understand that women can pursue careers as much as men. My boss (a woman) has three children and I have a baby myself. And therefore this client (a man) assumed that we wouldn’t be able to accompany him to the United States on a business trip. He had to go to the States at the end of February and he told his boss that he was sure that we wouldn’t go with him, since we were women and would want to stay at home. Needless to say, both of us were on the plane with him. He asked us who was taking care of our children then. So I joked that it should be no problem for them to sleep outside for a week – to make clear to him that these children have fathers as well and that these fathers are just as capable to take care of them as we are. This client’s reaction really took me aback. Most of the time, you don’t encounter reactions like that, because the men have wives themselves who work. (f12)

While these examples aptly illustrate how expressive relations sometimes yielded uncomfortable situations for female professionals, this also affected their male counterparts:

The manager was a woman, and the client was a macho. He only saw her as a woman and not really as a consultant. He talked about that with me, and that made me feel uncomfortable. I found it difficult to deal with the fact that, in my opinion, he was crossing a boundary. (m9)

‘I used to prefer working with men, but now I’m starting to like working with women better. I find it easier to develop a relationship with them. It happened to me one time that I invited a (male) client and was alone with him at night. It was a disaster. Even if you are very clear and direct, such a situation can be a disaster. I generally have my boyfriend accompany me when I invite clients so that there can be no misunderstanding about the purpose of the evening.’ (f9)

Indeed, this sentiment was echoed by different male partners: ‘It matters, too, whether the client is a man or a woman. It’s tricky to regularly have dinner with a woman at a restaurant … ethically speaking’ (m9), ‘Or I tell them: I’m bringing my wife. You could bring your husband if you like’ (m14).

Our analysis of expressive differences proved very important in terms of male–female informal client relationships. On the one hand, expressive differences explain the differences in instrumental approaches between female and male professionals, in that male professionals – counterintuitively – more readily sought to develop personal and emotional relationships with their clients, whereas women tended to maintain more professional distance. On the other hand, expressive differences also sometimes inhibited the development of a business relationship, yielding uncomfortable or forced situations. To avoid these situations, both men and women sometimes avoided informal relationships with clients of the opposite sex. However, in the persistently male-dominated business sector of professional services, this strategic response is likely to have a more significant influence on women than on men, in terms of strengthening the capital deficits deriving from their network.

Results of the semantic analysis

To verify our interpretive findings, we conducted a semantic analysis. The semantic study can be interpreted at two levels. First, simply by looking at the structure of the network diagrams, we see that there is more conformity in word use among the male informants than among the female informants, reflected in three core frames (word clusters with high co-word correlations), versus four core frames, respectively. Moreover, the words (nodes) are less densely interconnected in the female network than in the male network, which means that women use a greater variety of words to describe the same phenomena (as the same interview questions were used). (semantic network male informants) and (semantic network female informants) show these differences.

Second, looking at the actual content of the frames, we can identify differences between the groups. Starting with the male informants (see ), frame 1 describes the types of activities which they are most likely to engage in (‘restaurant’, ‘lunch’, ‘contact’) and emphasizes the informal nature of their client contacts (‘talk’, ‘guy’). Frame 2 indicates their instrumental orientation (‘contract’, ‘firm’, ‘sign’), but acknowledges the significance of expressive relationships to realize such goals (‘build’, ‘trust’). Finally, frame 3 shows a subtle emphasis on the business situations (‘organization’, ‘situation’), finding the right person (‘level’), and evaluating their suitability for informal client contact (‘typically’, ‘occasion’, ‘customer’, ‘able’, ‘understand’) ().

In the female informant network, frame 1 reflects a focus which the interpretive analysis did not disclose, namely the need to develop informal networking skills through training and mentoring (‘training’, ‘senior’, ‘junior’), adhering to formal organizational guidelines (‘code’). Frame 2 furthers this thread, emphasizing the formal rules which dictate their business engagements (‘rule’, ‘formal’, ‘business’, ‘firm’). Frame 3 manifests some instrumental details related to informal interaction (‘invite’, ‘lunch’, ‘dinner’), disclosing some of the expressive dimensions (‘friend’, ‘team’), but maintaining professional boundaries (‘company’, ‘professional’). Finally, frame 4 interestingly discloses some dimensions related to the process of establishing informal client relations, expressing quite clearly informants’ doubts (‘difficult’, ‘try’, ‘potential’, ‘maybe’).

These findings reflect some subtle differences, namely that male professionals seek to establish close, personal contact, but ultimately clearly oriented toward business outcomes of signed contracts. Female professionals more strongly emphasized the institutional boundaries of the profession and organization, and more explicitly recognized the strategic, developmental process underlying their efforts of building rapport. These findings not only add to our interpretive analysis but also confirm the significance of both instrumental and expressive relationships, while touching on some of the difficulties that top-ranking service professionals encounter in their efforts to establish these relationships. Having illustrated our findings, in the following section, we will now discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our study.

Discussion

This study aimed to identify how top-ranking service professionals apply expressive and instrumental means to develop client relationships, by studying differences in emotional bonding among male and female service professionals, and in their interactions with clients. This is an important question; namely, given the increasing heterogeneous work force that is also permeating the top ranks of service industries, increasing industry pressures and the stronger sector regulation, professionals are faced with new challenges in terms of developing their informal client relationships. Indeed, homophilious tendencies strengthen these pressures, as people tend to relate emotionally to people with similar attributes such as gender, race, and education (Casciaro, Citation2014; Ibarra, Citation1992). By generating a better empirical and theoretical understanding of different networking strategies given these pressures, service professionals will be better equipped to adapt their client relationship development.

As we anticipated, top-ranking service professionals – irrespective of their gender – emphasized the importance of investing time and resources on informal client relationship development, aimed toward establishing a long-term trusted relationship with clients in order to ensure repeat business in a competitive market under increased institutional pressures. The main differences related to the strategic use of informality, the choice of locations, and content of informal client contact, echoing prior studies (e.g. Taminiau et al., Citation2013). However, underlying these generally subtle differences were variations in using instrumental and expressive networking styles.

Our study confirmed that male partners often more consciously adopted instrumental business approaches, for instance, strategically distinguishing which clients they invested more in, with the purpose of attaining emotional bonds with the larger clients by inviting them to exclusive spaces and events, and opening up their networks to them. Although prior studies have already established this kind of behavior among service professionals (Sturdy et al., Citation2006.), we showed how service professionals purposefully took clients out of their comfort zones (namely, the conventional business setting of the office) and encourage relationship development at a more personal level, drawing on emotional bonding. Encouraging the expression of emotions was a conscious strategy toward further strengthening the business relationship.

Female top-ranking service providers deliberately kept a certain distance throughout their business contacts, preferring to maintain working hours for client contacts, and meeting at neutral locations. In so doing, they intentionally guarded professional boundaries between themselves and their – mostly – male clients. In fact, the results showed that the relationship between female partners and male clients still remains emotionally charged. This more reserved attitude was described by the female informants themselves as ‘professional behavior’, and tended to remain less expressive, but rather instrumental throughout their client contact. However, this professional distance did not represent a lack of commitment or involvement, as extensive preparations prior to client meetings conveyed.

Our study substantiates what different expressive and instrumental networking styles actually comprise of, and how these differences are manifested in practice among male and female service professionals. Our results show that women deploy less attention to networking styles with regard to their external relations, in contrast to their male counterparts. Indeed, male service professionals often approached informal client contact in a calculated and target-oriented manner, as ‘players’ of a business game to be won (Bensaou, Galunic, & Jonczyk-Sédès, Citation2013; Taminiau & Ferguson, Citation2015). This view of – and approach to – informal client contact is in line with other typically ‘male’ career-enhancing tactics that have been identified in prior studies (Anderson-Gough et al., Citation2005; Ibarra, Citation1992; Singh, Kumra, & Vinnicombe, Citation2002). However, women tend to possess a larger and more diverse network. This is consistent with Ibarra’s earlier findings (Citation1992), which describe how men seek out instrumental networking while women have more diverse purposes in their networking structures, both instrumental and expressive. However, we extend these prior studies of within-firm analyses, turning the focus outward by identifying whether and how gender differences are manifested in professionals’ networking styles with clients outside the firm, and how these differences contribute to establishing and maintaining their client contacts.

Furthermore, we advance understanding of developing informal client relationships by showing that there are two sides to expressive networks, but which are manifested in counterintuitive ways. Namely, the use of expressive and emotional repertoires is stereotypically more associated with female networking style, but we found that male service professionals are often more preoccupied with expressive relationships with their clients (who are mostly men), seeking closeness and for emotional intimacy based on common ground and feeling of fraternity (Arnould & Price, Citation1993). Indeed, we found that female service professionals are less emotionally bound to their clients and much more oriented toward maintaining a high level of professionalism, which calls for a certain distance and an emphasis on high-quality work.

In that sense, our study shows that women approach networking with their clients in a far more instrumental manner than previously expected, without taking the detour of developing an emotional bond as the men in our study seemed to do. Thus, our study denounces gender stereotyping in understanding social behavior, suggesting that it is more fruitful to study actual practices and deriving patterns from these. In so doing, we do not suggest that gender questions themselves are irrelevant, as clearly there is still much to be gained in terms of overcoming gender disparities; in fact, more in-depth analysis of male and female perceptions toward and responses to professional challenges can help reveal how different and conflicting social role expectations still prevail and constrain people toward further developing their full potential. Our study is a modest effort to contribute to this aim.

Despite the promise ingrained in our study, the more distant emotional involvement among women in developing informal client relations contains a potential risk. Namely, homophilious tendencies among both men and women tend to reinforce women’s network deficits, as long as females at top positions in the business world are in a minority. Thus, women remain at a disadvantage in terms of acquiring new business opportunities, as they are more restricted in their range of possibilities to build a trustful relationship with their clients, who are often men.

Oakley (Citation2000) describes two further gender-related origins of this deficit, which may contribute to a lower representation of women in senior management positions. The first explanation concerns barriers arising from objective justifications, such as their curriculum vitae: despite equal or superior qualifications, women are often more modest in listing their achievements. The second explanation is based on cultural and behavioral grounds, and relates to the so-called ‘double-bind’. Oakley posits that the characteristics generally ascribed to women are incompatible with a ‘male’ profession. She argues, for instance, that women who reach the partner level have ‘played the game’ according to what are perceived as ‘male’ rules. Dambrin and Lambert (Citation2012), who have studied the scarcity of top-ranking women in the accountancy sector, concur that women are often criticized when they act true to the female stereotype. Nonetheless, if a woman wishes to distinguish herself, and operates according to the male stereotype, she may be regarded as inauthentic. In many organizations, women in senior positions seek to downplay their femininity in order to enhance their credibility. However, such (more dominant) conduct may be perceived as role-crossing, or out-of-role behavior (Oakley, Citation2000; Singh & Vinnicombe, Citation2001), and may therefore be considered unfavorable (Hull & Umansky, Citation1997; Lehman, Citation1992). Nonetheless, such disadvantages might diminish over time (Singh, Vinnicombe, & James, Citation2006), as gradually increasing numbers of women are reaching top-ranking positions in professional services industries, leading to a more balanced distribution of female and male service professionals across the world.

Recommendations for further research

In this study, we sought to explain the instrumental use of client relationship development, showing how top-ranking male and female service professionals differed in their networking styles. While this study yielded some important outcomes, these could clearly be further developed through both empirical and theoretical follow-up research. For instance, in this study, we did not attend to possible cultural differences of influence on our findings. This was because we first wanted to identify which differences were manifested in practice at a micro level. However, it could be useful to analyze how cultural dimensions mediate the findings presented here.

Furthermore, more research is needed on career development in the context of our study, to determine what kind of socializing processes or coping strategies high-ranking female professionals develop, based on the professional norms required to reach the top. This could be particularly interesting in a context where business counterparts are female, rather than the male-dominated context of our research.

Practical implications

In order to succeed in a business context, acquiring contracts is an important criterion (Kumra & Vinnicombe, Citation2008). Informal client relationships play an important role in this regard (Czarniawska & Mazza, Citation2003; Levin & Cross, Citation2004; Sturdy et al., Citation2006; Taminiau et al., Citation2013). This study has provided insights into the different ways in which top-ranking women and men within large professional service organizations use networking styles in informal client contact, which is primarily important toward fostering understanding of how to maintain a competitive edge within professional service firms, and more effectively drawing from a firm’s talent pool. Namely, more in-depth understanding of what different people are good at, can help firms more strategically determine which human resources to deploy toward particular aims.

Furthermore, while this study does not specifically deal with advancement opportunities, its results do offer useful insights into how organizations can better support women’s career advancement. This is important in view of the lagging numbers of female service professionals in the upper ranks of the service industries, while diversity has been proven to foster performance (e.g. Campbell & Mínguez-Vera, Citation2008; Dwyer, Richard, & Chadwick, Citation2003). Indeed, despite equal educational backgrounds, women still remain underrepresented compared to men in management and partner positions at consultancy and accountancy organizations; for example, in the USA, only 17% of the CPA (Certified public accountants) partners are women at firms –with 50 staff or more.Footnote3 Our study provides insights into relevant points of attention, showing where potential sources of imbalance derive from.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The total dataset comprised a total of 250 interviews with professionals in the service industry, located in Belgium, (N = 18), Canada (N = 40), France (N = 19), Germany (N = 18), Italy (22), Netherlands (49), Spain (12), Sweden (21), Switzerland (15), United Kingdom (15) and Unites States (21).

2. Factor analyses were conducted with Oblimin rotation, whereby we deleted items with factor loadings of less than 0.60, or with high cross-loadings on other factors. Each of the factors thus yielded Cronbach’s alphas above 0.7, thereby meeting the standard research requirements.

3. This information is available from the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) in the form of a speech by Ms. Jeanette M. Franzel, March 13th 2014, Leadership in public accounting firms: Why so few women?. Retrieved from https://pcaobus.org/News/Speech/Pages/03132014_Washington_Women.aspx

References

- Anderson-Gough, F., Grey, C., & Robson, K. (2005). It’s a case of helping them to forget: The organizational embedding of gender relations in public audit firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(5), 469–490. doi: 10.1016/j.aos.2004.05.003

- Appelbaum, S. H., & Steed, A. J. (2005). The critical success factors in the client-consultant relationship. Journal of Management Development, 24(1), 68–93. doi: 10.1108/02621710510572362

- Armbrüster, T. (2006). The economics and sociology of management consulting. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Arnould, E., & Price, L. (1993). River magic: Extraordinary experience and the extended service encounter. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(1), 24–45. doi: 10.1086/209331

- Awazu, Y. (2004). Informal network players, knowledge integration, and competitive advantage. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(3), 62–70. doi: 10.1108/13673270410541042

- Batagelj, V., & Mrvar, A. (2004). Pajek – analysis and visualization of large networks. Berlin: Springer.

- Bensaou, B., Galunic, C., & Jonczyk-Sédès, C. (2013). Players and purists: Networking strategies and agency of service professionals. Organization Science, 25(1), 29–56. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2013.0826

- Campbell, K., & Mínguez-Vera, A. (2008). Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(3), 435–451. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9630-y

- Casciaro, T. (2014). Affect in organizational networks. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 40, 219–238. doi: 10.1108/S0733-558X(2014)0000040011

- Ceron-Anaya, H. (2010). An approach to the history of golf: Business, symbolic capital, and technologies of the self. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 34(3), 339–358. doi: 10.1177/0193723510377317

- Ciancanelli, P., Gallhofer, S., Humphrey, C., & Kirkham, L. (1990). Gender and accountancy: Some evidence from the UK. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 1(2), 117–144. doi: 10.1016/1045-2354(90)02011-7

- Czarniawska, B., & Mazza, C. (2003). Consulting as a liminal space. Human Relations, 56(3), 267–290. doi: 10.1177/0018726703056003612

- Dambrin, C., & Lambert, C. (2012). Who is she and who are we? A reflexive journey in research into the rarity of women in the highest ranks of accountancy. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 23(1), 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cpa.2011.06.006

- Ding, W. W., Murray, F., & Stuart, T. (2013). From bench to board: Gender differences in University scientists’ advisory boards. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1443–1464. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.0020

- Dwyer, S., Richard, O. C., & Chadwick, K. (2003). Gender diversity in management and firm performance: The influence of growth orientation and organizational culture. Journal of Business Research, 56(12), 1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00329-0

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

- Fullerton, J., & West, M. A. (1996). Consultant and client – working together? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 11(6), 40–49. doi: 10.1108/02683949610129749

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. doi: 10.1177/1094428112452151

- Glückler, J., & Armbrüster, T. (2003). Bridging uncertainty in management consulting: The mechanisms of trust and networked reputation. Organization Studies, 24(2), 269–297. doi: 10.1177/0170840603242004

- Hislop, D. (2002). The client role in consultancy relations during the appropriation of technological innovations. Research Policy, 31(5), 657–671. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00135-4

- Höner, D., & Mohe, M. (2009). Behind clients’ doors: What hinders client firms from ‘professionally’ dealing with consultancy? Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(3), 299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2009.05.006

- Hull, R. P., & Umansky, P. H. (1997). An examination of gender stereotyping as an explanation for vertical job segregation in public accounting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(6), 507–528. doi: 10.1016/S0361-3682(96)00028-1

- Ibarra, H. (1992). Homophily and differential returns: Sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(3), 422–447. doi: 10.2307/2393451

- Ibarra, H. (1997). Paving an alternative route: Gender differences in management networks. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60(1), 91–102. doi: 10.2307/2787014

- Johnson, M., & Selnes, F. (2004). Customer portfolio management: Toward a dynamic theory of exchange relationship. Journal of Marketing, 68(2), 1–17. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.68.2.1.27786

- Kaiser, S., Müller-Seitz, G., & Creusen, U. (2008). Passion wanted! Socialisation of positive emotions in consulting firms. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 2(3), 305–320. doi: 10.1504/IJWOE.2008.019428

- Karantinou, K., & Hogg, M. (2010). Exploring relationship management in professional services: A study of management consultancy. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(3), 263–286.

- Kiely, J. (2005). Emotions in business-to-business service relationships. The Service Industries Journal, 25(3), 373–390. doi: 10.1080/02642060500050517

- Kipping, M., & Engwall, L. (2002). Management consulting: Emergence and dynamics of a knowledge industry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kitay, J., & Wright, C. (2004). Take the money and run? Organisational boundaries and consultants’ roles. The Service Industries Journal, 24(3), 1–18. doi: 10.1080/0264206042000247731

- Kumra, S., & Vinnicombe, S. (2008). A study of the promotion to partner process in a professional services firm: How women are disadvantaged. British Journal of Management, 19(S1), S65–S74. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2008.00572.x

- Lehman, C. R. (1992). ‘Hestory’ in accounting: The first eighty years. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 17(3/4), 261–85. doi: 10.1016/0361-3682(92)90024-M

- Levin, D. Z., & Cross, R. (2004). The strength of weak ties you can trust: The mediating role of trust in effective knowledge transfer. Management Science, 50(11), 1477–1490. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1030.0136

- Leydesdorff, L., & Welbers, K. (2011). The semantic mapping of words and co-words in contexts. Journal of Informetrics, 5(3), 469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2011.01.008

- Lin, N. (2000). Inequality in social capital. Contemporary Sociology, 29(6), 785–795. doi: 10.2307/2654086

- McDonald, S., Lin, N., & Ao, D. (2009). Networks of opportunity: Gender, race, and job leads. Social Problems, 56(3), 385–402. doi: 10.1525/sp.2009.56.3.385

- McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

- Metz, U., & Tharenou, P. (2001). Women’s career advancement: The relative contribution of human and social capital. Group and Organization Management, 26(3), 312–342. doi: 10.1177/1059601101263005

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Mohe, M. (2008). Bridging the cultural gap in management consulting research. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 8(1), 41–57. doi: 10.1177/1470595807088321

- Morand, D. A. (1995). The role of behavioral formality and informality in the enactment of bureaucratic versus organic organizations. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 831–872.

- Nikolova, N., Mollering, G., & Reihlen, M. (2015). ‘Trusting as a ‘Leap of Faith’: Trust-building practices in client – consultant relationships’. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(2), 232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2014.09.007

- Nikolova, N., Reihlen, M., & Schlapfner, J. F. (2009). Client-consultant interaction: Capturing social practices of professional service production. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(3), 289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.scaman.2009.05.004

- Oakley, J. G. (2000). Gender-based barriers to senior management positions: Understanding the scarcity of female CEO’s. Journal of Business Ethics, 27(4), 321–334. doi: 10.1023/A:1006226129868

- O’Mahoney, J., & Markham, C. (2013). Management Consultancy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Sealy, R., & Vinnicombe, S. (2012). The female FTSE Board Report 2012: Milestone or millstone? Cranfield: Cranfiel School of Management.

- Singh, V., Kumra, S., & Vinnicombe, S. (2002). Gender and impression management: Playing the promotion game. Journal of Business Ethics, 37(1), 77–89. doi: 10.1023/A:1014782118902

- Singh, V., & Vinnicombe, S. (2001). Impression management commitment and gender: Managing other’s good opinions. European Management Journal, 19(2), 183–194. doi: 10.1016/S0263-2373(00)00093-1

- Singh, V., Vinnicombe, S., & James, K. (2006). Constructing a professional identity: How young managers use role models. Women in Management Review, 21(1), 67–81. doi: 10.1108/09649420610643420

- Stalnaker, R. (2002). Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy, 25(5), 701–721. doi: 10.1023/A:1020867916902

- Sturdy, A. (2011). Consultancy’s consequences? A critical assessment of management consultancy’s impact on management. British Journal of Management, 22(3), 517–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00750.x

- Sturdy, A., Schwarz, M., & Spicer, A. (2006). Guess who’s coming to dinner? Structures and uses of liminality in strategic management consultancy. Human Relations, 59(7), 929–960. doi: 10.1177/0018726706067597

- Taminiau, Y. (2013). ‘It looks like friendship but it is not’: The institutional embeddedness of informal client relationships of big 4 accountants and consultants compared. International Journal of Management Concepts and Philosophy, 7(2), 128–149. doi: 10.1504/IJMCP.2013.055721

- Taminiau, Y., Berghman, L., & Den Besten, P. (2013). Informal client relationship development by consultants: The star players and the naturals. In A. Buono, L. de Caluwé, & A. Stoppelenburg (Eds.), Exploring the Professional Identity of Management Consultants (pp. 51–71). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

- Taminiau, Y. T. A., & Ferguson, J. E. (2015). From purists players? How service industry professionals develop social skills for informal client relationships. International Journal of Management Concepts and Philosophy, 9(1), 40–62. doi: 10.1504/IJMCP.2015.075122

- Van Eck, N., & Waltman, L. (2009). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

- Williams, T. A., & Shepherd, D. A. (2015). Mixed method social network analysis. Organizational Research Methods. doi:10.1177/1094428115610807