Abstract

In order to help viewers recognize the persuasive attempts of product placement (PP), broadcasters are obligated to present disclosures and, in most countries, those disclosures must be presented repeatedly. The repeated inclusion of disclosures is especially important when it comes to children who are less equipped to detect persuasive messages compared to adults. To date, however, the role of disclosure repetition for children’s cognitive processing is unclear. Hence, we conducted an eye-tracking study with 105 children to shed light on the effect of disclosure repetition on children’s implicit cognitive processing of PP (i.e., attention toward the placement). Results demonstrated that disclosure repetition led to less attention toward the subsequently presented embedded brand compared to no and a one-time disclosure. Additionally, more attention triggered the explicit activation of persuasion knowledge. Age did not moderate this effect. Overall, the findings underline the importance of disclosure repetition to shield children against persuasive influence.

Introduction

In the film series ‘Hotel Transylvania’, the production company SONY seizes the chance and promotes their products to their young audience. Hence, we can see Dracula use his SONY phone and show off several functions of the product, as well as some strategic non-interactive presentations of the VAIO laptops throughout the movie. Such brand appearances are omnipresent in audiovisual content suitable for children and they constitute a particular advertising technique, called ‘product placement’ (Naderer, Matthes, and Spielvogel Citation2019). Product placement (referred to as PP in the following) describes an advertising technique that embeds branded products or services either visually, verbally or audio-visually into entertaining media content such as TV-series, movies, or games (Balasubramanian, Karrh, and Patwardhan Citation2006). Thus, this advertising technique blurs the line between entertainment and commercial content and viewers may not be able to recognize the persuasive intent and source behind this ‘hidden’ commercial message (e.g., Matthes, Schemer, and Wirth Citation2007). As a consequence, targeting children and adolescents—who are still developing their cognitive abilities (Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010)—with PP has led to ethical concerns and has been critically discussed by parents and consumer advocacy groups (Hudson, Hudson, and Peloza Citation2008). Furthermore, confronting young viewers with persuasive messages, which they can hardly identify as advertising, have continuously been connected to several negative outcomes for children’s physiological and psychological health. For instance, a considerable body of literature indicates that children are persuaded by PP to eat unhealthy products (e.g., Folkvord et al. Citation2015; Naderer et al. Citation2018).

In order to inform the audience about the presence of advertising, members of the European Union (EU) are obligated to identify programs containing PP by the implementation of a disclosure (AVMSD Audiovisual Media Services Directive Citation2010). The impact of disclosures on the processing of branded content has been thoroughly investigated with adult viewers. Previous findings indicated that disclosing PP to adult viewers resulted in cognitive responses through the explicit activation of persuasion knowledge (PK; e.g., Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012). Disclosure studies also examined adults’ implicit cognitive activity by applying eye-tracking studies. These studies revealed an impact of disclosures on viewers’ attentional processing of branded content (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015; Smink, van Reijmersdal, and Boerman Citation2017; Guo et al. Citation2018). In contrast to research assessing the impact of PP disclosures on adults, a limited number of studies have investigated the influence of disclosures on children. Yet, initial results demonstrated that existing disclosures are hardly able to affect children’s and adolescent’s explicit recognition of PP as advertising or their understanding of the persuasive intent of these embedded persuasive messages, that is, conceptual elements of PK (De Jans et al. Citation2018; van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2017).

The EU further regulates by law that disclosures must be shown at the beginning of the program, after each commercial break, and at the end of the program (AVMSD Audiovisual Media Services Directive Citation2010). Although these legal regulations exist, the role of disclosure repetition for both adult and young viewers’ cognitive processing is not clear to date. This is a pressing research gap since there is a call for more externally valid research settings in this area of research compared to the somewhat artificial settings being used in the past (see for a review on disclosure studies Boerman and van Reijmersdal Citation2016). Against this background, previous research has either examined one-time disclosures at the beginning of the program or the impact of disclosure timing, but has so far not looked at disclosure repetition. Hence, external validity can be improved by replicating EU disclosure practices prescribed by law.

Furthermore, an investigation of disclosure repetition might be especially interesting when children are the target audience, because young consumers are viewed as processors that need to be particularly cued in order to cope with persuasive attempts (Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010; Hudders et al. Citation2017). There are thus reasonable grounds for supposing that disclosures might serve as a prime for children for the upcoming PP (De Pauw, Hudders, and Cauberghe Citation2018; De Jans et al. Citation2018). Our current knowledge, however, is inconclusive about whether ‘disclosures are used as a cue to ignore sponsored content or whether consumers’ attention is directed toward sponsored content to critically process it’ (Boerman and van Reijmersdal Citation2016, 142). In this light, recent research also lacks an investigation of the impact of children’s attention toward the PP on the activation of PK.

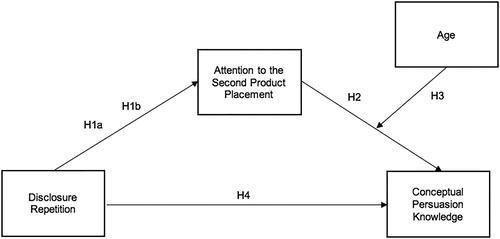

In sum, we aim to investigate the role of disclosure repetition by considering children’s implicit (i.e., visual attention) cognitive processing of PP. In line with findings on adult viewers (e.g., Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015), we were also interested in the influence of disclosures on the extent of visual attention toward the PP. Furthermore, we wanted to assess how the visual attention toward the PP affects children’s conceptual PK (referred to as ‘persuasion knowledge’). In addition to that, we intended to follow the literature on cognitive development by exploring the moderating role of age for the relationship between visual attention and PK (Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010; John Citation1999). Finally, we also tested whether disclosures are able to directly influence children’s activation of PK.

Children’s cognitive processing of PP

Young consumers process persuasive messages within media content in a different way than adults. A great body of previous literature traces this circumstance not only to the ‘hidden’ nature of embedded advertising techniques but also to children’s limited cognitive processing skills (e.g., Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010; Rozendaal et al. Citation2011). Against this background, the framework for children’s and adolescent’s processing of commercialized media content (PCMC) by Buijzen and others (Citation2010) adopted a developmental perspective on adult persuasion models. The PCMC distinguishes three types of cognitive persuasion processing. When consumers are highly able and motivated to process a persuasive message and also pay close attention to it, systematic processing occurs (Heath Citation2000; Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986). While systematic processing is characterized by an effortful cognitive elaboration, heuristic processing is defined by a moderate level of cognitive elaboration. In this case, recipients pay moderate to low attention to the persuasive message and also show moderate to low ability as well as motivation to process it (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986). Besides these two routes of persuasion processing, automatic processing indicates the most minimal level of cognitive elaboration and is therefore characterized by less to zero attention to the persuasive message as well as by less to zero ability and motivation to process the message (Heath Citation2000).

Concerning the special case of children, the PCMC argues that developmental changes during childhood lead to a sensitization for low elaborated processing mechanisms and to an inhibition to process a persuasive message more systematically. Furthermore, since children predominantly focus on the plot of an entertaining media program, only a limited amount of cognitive resources remain to process the PP (Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010). Hence, embedded persuasive messages such as PP make it challenging for children to process the advertising content systematically. However, based on previous literature, children’s explicit detection of the persuasive intent is a fundamental skill in the ‘embedded marketing world’ (Wright, Friestad, and Boush Citation2005). Several researchers thus argue that young consumers are better equipped to cope with PP when they get forewarned about the embedded persuasive messages with a disclosure (De Pauw, Hudders, and Cauberghe Citation2018; De Jans et al. Citation2018; Hudders et al. Citation2017).

Although PP disclosures can affect several areas of processing (i.e., cognitive and affective; see Boerman and van Reijmersdal Citation2016), this article focuses on cognitive elements of processing, because the main goal of disclosures is to make viewers aware of the presence of embedded advertising (Cain Citation2011).

Effects of disclosures on children’s cognitive processing of PP

In the EU, broadcasters are obligated to appropriately identify television programs containing PP by the implementation of a disclosure (AVMSD 2010). There is already a considerable number of studies which investigated the effects of PP disclosures on adults, testing either brand-specific (e.g., Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012; Dens, De Pelsmacker, and Verhellen Citation2018) or brand-unspecific disclosures (e.g., Campbell, Mohr, and Verlegh Citation2013). Most existing research on children, in contrast, primarily focuses on other advertising formats such as traditional television ads (Vanwesenbeeck, Opree, and Smits Citation2017), advergames (An and Stern Citation2011), or personalized advertising on social networking sites (Daems et al. Citation2019). Additionally, one study on PP disclosures refers to adolescents (van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2017) and only two more studies we are aware of have particularly looked at the effects of PP disclosures on children (De Jans et al. Citation2018; De Pauw, Hudders, and Cauberghe Citation2018). Despite the progress made, existing work on disclosures in connection with children has not investigated the role of disclosure repetition and did not sufficiently investigate the cognitive processes connected to disclosures.

In the following, we discuss how PP disclosures affect two different areas of cognitive processing of the upcoming branded content: The first step constitutes an implicit processing mechanism and refers to viewers’ attention toward PP while the second step refers to viewers’ explicit activation of PK (Boerman and van Reijmersdal Citation2016).

Implicit cognitive processing: attention toward PP

Persuasion processing is contingent on the amount of attention that recipients pay to a persuasive message (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986). To date, several studies with adults thus examined how PP disclosures affect viewers’ attention to the upcoming PP. These studies applied a brand memory measurement as an indicator for attention (e.g., Campbell, Mohr, and Verlegh Citation2013; Dens, De Pelsmacker, and Verhellen Citation2018). Some studies have also addressed attention more directly by measuring the amount of visual attention individuals pay to the PP through the method of eye-tracking (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015; Guo et al. Citation2018; Smink, van Reijmersdal, and Boerman Citation2017). Yet existing findings so far are inconclusive on whether disclosures are used to direct attention toward the brand (e.g., Guo et al. Citation2018) or lead recipients to ignore the branded content (Boerman and van Reijmersdal Citation2016). In the following, we present two competing theoretical explanations and corresponding empirical results for both outcomes.

Higher levels of attention to PP

One theoretical explanation for higher levels of attention to the branded content is priming. Based on this theory, a disclosure can function as a prime for the inserted brand (see Balasubramanian, Karrh, and Patwardhan Citation2006), leading to a higher likelihood of PP processing (Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). In other words, stimuli related to the disclosure gets primed and this priming process simplifies the processing of the PP. In this context, eye-tracking studies with adults demonstrated that PP disclosures triggered systematic processing of the branded content by increasing visual attention (Guo et al. Citation2018) for both prominent (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015) and subtle PP (Smink, van Reijmersdal, and Boerman Citation2017). Another recent disclosure study examined the role of placement frequency and revealed disclosure effectiveness for both moderately frequently and frequently depicted PP as participants’ brand memory increased in both cases (Matthes and Naderer Citation2016). Taken together, priming theory supports higher levels of attention toward the branded content triggered by a prior disclosure.

Lower levels of attention to PP

Current literature, however, contrasts the priming effect with a concept of a reversed priming effect. Several studies of Laran, Dalton, and Andrade (Citation2011) demonstrate that priming recipients with an advertising slogan might trigger automatic cognitive processes and behavioral reactions that go in the opposite direction of the meaning of the slogan. ‘This effect occurs because slogans are automatically perceived as persuasion tactics and thus prompt adoption of an unconscious goal to correct and hence to resist such tactics’ (Fransen and Fennis Citation2014, 920). Most importantly, this process operates entirely outside of conscious awareness (Laran, Dalton, and Andrade Citation2011). Hence, since a disclosure aims to make consumers aware of the upcoming persuasive content (Cain Citation2011), consumers may tend to resist the PP without being aware of doing so. This circumstance may also explain the likewise existing empirical evidence for a negative effect of PP disclosures on brand recall in adult viewers (Campbell, Mohr, and Verlegh Citation2013). Interestingly, a study on disclosing advergames of An and Stern (Citation2011) also found lower brand recall in children who were exposed to a disclosure cue prior to the game compared to children who saw no disclosure. Taken together, a body of research supports lower levels of attention toward the branded content triggered by a prior disclosure.

Implicit cognitive processing of PP and the role of disclosure repetition

The EU regulates by law that disclosures must be shown at the beginning of the program, after a commercial break, and at the end of the program (AVMSD 2010). The underlying idea is that disclosure repetition might increase consumers’ awareness and understanding of the disclosure (Hoy and Andrews Citation2004). However, the currently available body of research does not inform us whether disclosure repetition is of key importance and how repeated disclosure cues affect viewers’ cognitive processing of the upcoming branded content. Since disclosure repetition is required by law (AVSMD 2010), we aim to derive the potential effects of disclosure repetition on the implicit cognitive processing (i.e., visual attention) of the subsequently presented PP.

In this light, literature on the practice of PP suggests that a repetition of a stimuli is one of several PP characteristics that not only influences brand attitudes (i.e., known as the mere exposure effect; Matthes, Schemer, and Wirth Citation2007) but also the cognitive processing of branded content (as an indicator of attention; van Reijmersdal, Neijens, and Smit Citation2009). Yet, again there are two possible outcomes: On the one hand, repetition can enhance the processing of information, leading to an increase of attention and on the other hand, ‘too much repetition might backfire because of a lack of viewer motivation to process the message’ (van Reijmersdal, Neijens, and Smit Citation2009, 433).

However, these insights only refer to the repetition of the target stimuli (here: PP) but not to the repetition of the prime (here: disclosure). Based on the concept of priming, the likelihood of a priming effect not only increases with a short time delay but also with the frequency of the prime (Roskos-Ewoldsen, Roskos-Ewoldsen, and Carpentier Citation2002). That is, priming recipients repeatedly might enhance the respective effect: In the case of a priming effect, viewers should show more attention to the PP with increasing disclosure repetition. However, in the case of a reversed priming effect, the disclosure might serve as a prime to avoid the subsequent brand presentations. Hence, the attention to the subsequent target stimuli (i.e., the PP) with increasing disclosure repetition should decrease.

To reiterate, based on the theoretical foundations outlined above, an investigation of the effect of disclosure repetition on attention to the upcoming PP leads to two competing assumptions. Thus, we aim to investigate which argument is true: On the one hand, when following priming theory (Roskos-Ewoldsen, Roskos-Ewoldsen, and Carpentier Citation2002), a PP disclosure might prime children about the upcoming branded content and thus draw their attention toward the PP (De Pauw, Hudders, and Cauberghe Citation2018). Additionally, repetition of a disclosure may enhance this effect compared to a one-time disclosure and no disclosure at all. On the other hand, in line with the concept of a reversed priming effect (Fransen and Fennis Citation2014), a PP disclosure might lead to less attention toward the subsequently presented PP (An and Stern Citation2011). Again, disclosure repetition may enhance this effect compared to a one-time disclosure and to no disclosure at all. In the following, both arguments are stated as competing hypotheses:

H1a: A repeated exposure to a disclosure will lead to more visual attention toward the subsequently presented PP compared to a one-time disclosure and no disclosure.

H1b: A repeated exposure to a disclosure will lead to less visual attention toward the subsequently presented PP compared to a one-time disclosure and no disclosure.

Explicit cognitive processing: activation of PK

A great part of research on PP disclosures theoretically relates to the Persuasion Knowledge Model (PKM) by Friestad and Wright (Citation1994). According to this framework, the term ‘persuasion knowledge’ (PK) refers to the consumers’ ability to recognize a persuasive message and understand its persuasive intent. In the persuasion literature, the activation of such PK predominantly relies on a conscious and an effortful awareness (Fransen and Fennis Citation2014). Thus, previous studies used explicit measures to assess the recipient’s level of PK.

Attention as an indicator for activation

Based on adult persuasion models, the likelihood of systematic processing of the persuasive message increases as soon as recipients focus their attention on a persuasive message (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986). Systematic processing, in turn, appears to be a crucial indicator for activation of PK (‘critical systematic processing’; see Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010). In other words, the activation of PK depends on the intensity of processing of persuasive messages. Against this background, results of existing studies with adult viewers revealed mediated effects on PK via visual attention toward the PP triggered due to a prior disclosure (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015; Smink, van Reijmersdal, and Boerman Citation2017). Therefore, visual attention to the upcoming PP is viewed as an important precondition for PK to emerge (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015).

Since how disclosure repetition affects visual attention toward the upcoming placement is not clear as of now (see Hypothesis 1a versus Hypothesis 1b), we aim to investigate the direct effect of visual attention toward the PP on PK. Based on findings of previous studies with adult viewers who highlighted the key importance of visual attention for the activation of PK (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015), we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: More visual attention toward the PP will lead to activation of PK.

The moderating role of age

Several previous theoretical models also stress the important role of age when considering the development of PK (for a review see Wright, Friestad, and Boush Citation2005). According to these models, PK up to a certain point increases with age (i.e., during phases of cognitive development hence in the transition from childhood to youth). Based on propositions introduced by the PKM (Friestad and Wright Citation1994), practical experience with specific advertising techniques determines the development of children’s understanding of persuasion (Wright, Friestad, and Boush Citation2005). Therefore, older children (approaching the age of 12) are expected to have a better fundamental understanding of persuasion tactics and thus are assumed to be more able to cope with PP than younger children (around the age of 6). By theoretically building on children’s developmental phases originally put forth by Piaget (Citation1929), the widespread stage model of consumer socialization posited by John (Citation1999) also indicated the necessity of a certain level of cognitive development in order to cope with advertising. Next to these insights of developmental psychology and domain-specific content knowledge, the PCMC (Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010) also stressed the importance of age when considering children’s processing skills in the special case of embedded persuasive messages.

In our study, we refer to children between the ages of 6 and 11 and hence investigate the developmental phases of middle (6–9 years) and late childhood (10–12 years; see Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010). Thus, this gives us the possibility to examine the role of cognitive development as a moderating factor in the understanding of persuasive messages. While the information-processing skills of children in middle childhood are not yet fully developed, young recipients in late childhood possess the abilities to process persuasive messages on a more elaborate level (Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010). Therefore, we assume that age might strengthen the direct effect of children’s visual attention toward the PP on activation of PK. In other words, while paying attention to the PP older children might be more able to correctly translate the persuasive message by explicitly recalling its persuasive attempts compared to younger children.

H3: Age moderates the direct effect of visual attention toward the PP on children’s subsequent level of PK.

Disclosures and PK

Based on the PKM (Friestad and Wright Citation1994), the essential goal of a disclosure is to help consumers be aware of the presence of a persuasive message (Cain Citation2011). Indeed, a great part of research on adults demonstrated a positive effect of a prior PP disclosure on PK (e.g., Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012). Regarding findings with young consumers, De Pauw and others (Citation2018) were the first who found that disclosing PP visually before a movie excerpt directly affected awareness of the persuasive intent of children (aged 8–10). However, De Jans et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that the existing PP disclosure led to poorer advertising recognition in children (aged 10–11) compared to a self-created disclosure more suitable for children. In addition, a study with adolescents only showed PP disclosure effects on participants’ understanding of persuasive intent while other aspects of PK remained unaffected (van Reijmersdal et al. Citation2017).

While attention toward the branded content might be an important indicator for the activation of PK (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015; Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010; Smink, van Reijmersdal, and Boerman Citation2017), the disclosure itself may also directly indicate the activation of PK. Matthes and Naderer (Citation2016) showed for the first time that disclosures also affect participants who were not actually exposed to PP at all. Interestingly, their results revealed that even when no placements were present the mere presence of a PP disclosure activated PK. In other words, PK crept up although the target brand was not present and the participants were thus not able to pay attention to the placement. This suggests that merely seeing a disclosure may activate a schema indicating that advertising will be shown.

It thus may be possible that not only attention toward the brand may activate PK, but a disclosure itself may directly influence children’s level of PK compared to no disclosure.

H4: Exposure to a disclosure will lead to the activation of PK compared to no disclosure.

See for the conceptualized model.

Method

Design, sample, and procedure

We conducted a single-factorial (disclosure repetition) experimental study with children. Independently of the present study, another experimental study took place at the same time. The participating children were randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions (repeated disclosure vs. one-time disclosure vs. no disclosure). The study combined eye-tracking measurements with survey data. The eye movements of the children were recorded during the reception with a remote eye-tracking system (SMI iView X™ RED). Through the application of an eye-tracking device we gain insights into how intensively viewers consider certain visual information (here: PP). Regarding the special case of children in connection with embedded advertising, eye-tracking is a commonly used method for investigating children’s visual attention toward placements in audiovisual media (e.g., Folkvord et al. Citation2015). Between the ages of 4 and 6 children develop their viewing skills and from this age range on, children’s gaze behavior becomes similar to the gaze behavior of adults when viewing video content (Kirkorian, Anderson, and Keen Citation2012). Hence, the cognitive processing of PP of children (6–11 years old) can be assessed by an eye-tracking device. To test whether the eye-tracking procedure was easy to follow for children within this age range we furthermore conducted a pre-test with eight children aged 6–12 years (62.5% female; Mage = 8.63, SD = 2.07). The pre-test indicated that the procedure was appropriate for children as participants.

We collected the data in four primary schools in Austria in June 2018. Initially, 117 children aged 6–11 years participated in the study. We excluded nine children because of poor deviation results following calibration and another three children due to severe language issues in the oral interviews. Hence, the final data set consisted of N = 105 children (44.8% female; Mage = 8.36; SD = 1.29). The number of cases in our study exceeds those of previous eye-tracking studies with children working with a similar design (e.g., De Jans et al. Citation2018).

We obtained parents’ written and children’s oral consent prior conducting the study. One female experimenter conducted the eye-tracking study with the children. At the beginning of the eye-tracking session, the experimenter seated the children individually in front of the eye-tracker and explained the procedure followed by a five-point calibration. After the stimulus presentation, the experimenter conducted a five-point validation (for this procedure, see e.g., Spielvogel et al. Citation2018). The duration of the eye-tracking session (starting with calibration) ranged from 3:11 to 3:36 minutes. Afterward, individual interviews with the children assessing explicit disclosure memory, their level of PK and prior cartoon exposure were conducted.

Stimulus material

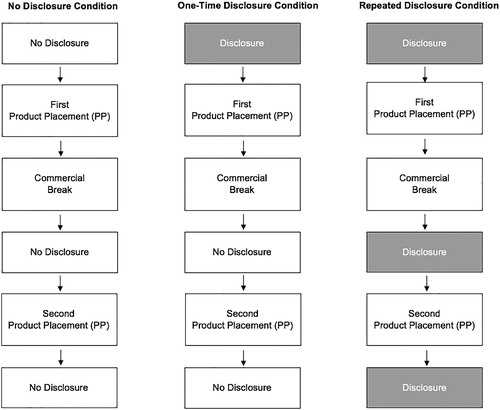

All the participating children were exposed to a narrative cartoon of ‘Alvin and the Chipmunks’ (from a popular children’s channel in Austria). The movie lasted 3:07 minutes and presented the story of three chipmunks organizing a pool party. The cartoon was interrupted by a short commercial break (20 seconds), which presented a self-created commercial about a fictional lemonade.

We created three versions of the movie, which varied in the frequency of the disclosure. In the repeated disclosure condition (n = 37), children saw the disclosure three times (i.e., at the beginning, after the commercial break, and at the end), while children in the one-time disclosure condition (n = 37) were only exposed to one disclosure at the beginning of the movie. In the control condition (n = 31), children saw no disclosure at all. The employed disclosure matched the current disclosure application of the Austria’s public broadcasting disclosure. The disclosure presented a P-symbol with an additional text (‘Sponsored by Product Placement’) at the top of the screen. Each disclosure appeared for six seconds (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2012).

In all versions of the movie, one author with excellent Adobe Photoshop skills inserted the PP. We used the existing brand Utz because this brand is commonly present in the cinema movies of Alvin and the Chipmunks. In line with previous eye-tracking studies (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015), the movie included cheeseballs of the brand Utz two times: at the beginning of the stimuli (first PP appearance) and after the commercial break (second PP appearance). Overall, the brand Utz was shown for 36.5 seconds (first PP appearance: 17.5 sec; second PP appearance: 19 sec). For the present study, the second PP appearance is our placement of interest, because at this time the manipulation of disclosure repetition was completed. Hence, the differences in the type of integration between the first and the second PP (regarding size and duration) were of no concern to the study: First, the brand was inserted the exact same way in all three conditions. Second, we did not attempt to compare the first and second PP appearance in any way (see ‘Measures’ section). visualizes the research design.

Measures

Visual attention toward the PP

To assess the cognitive processing of brands connected to disclosures on an implicit level, we measured children’s visual attention toward the second PP appearance. We recorded the data with a sampling rate of 120 Hz. Viewing was binocular, yet only the right eye's movements were monitored.

We defined each PP appearance as one area of interest (AOI). The coverage of the AOIs varied between 1.6% (first PP appearance) and 8.2% (second PP appearance). For our main analysis, only the AOI for the second PP appearance is relevant, since at this time our manipulation of disclosure repetition was completed (see ). For the AOI, we calculated dwell time that provides information about total viewing time (i.e., sum of fixations and saccades in milliseconds; King et al., Citation2019). The second PP appearance lasted 18,910 milliseconds overall and comprised several frames containing PP. Each of these frames had a different duration. Therefore, we standardized children’s dwell time by dividing their dwell time by the total exposure time of each frame. In a final step, we calculated a mean index for the second PP appearance which included the standardized dwell time scores of all frames (M = .20; SD = .15; referred to as ‘standardized dwell time’ in the following). Through this procedure, we gained a more accurate indication of children’s dwell time scores for the second PP appearance.

Activation of PK

Since we were also interested in cognitive processing mechanisms on an explicit level, our measurement furthermore refers to the conceptual elements of PK. In a qualitative in-depth pretest with two children (9 and 11 years old) we tested both the liking of the stimulus as well as children’s understanding of the questions.

We assessed children’s PK with two concepts based on van Reijmersdal, Rozendaal, and Buijzen (Citation2012): The first concept refers to children’s understanding of the persuasive intent (‘Why do you think the Chipmunks had cheeseballs with them?’ So that you would like to eat cheeseballs? (correct); Because the Chipmunks like to eat cheeseballs?; Because your teacher likes to eat cheeseballs?). The second concept relates to the understanding of the source by asking the children: ‘Who do you think inserted the cheeseballs into the movie?’ (The company which produces the cheeseballs? (correct); The supermarket which sells the cheeseballs?; We, the researchers of the university?). In order to indicate children’s PK, we summarized both questions to a formative index, ranging from ‘0 = no PK’ to ‘2 = high PK’ (for this procedure, see Naderer et al. Citation2018). Overall, most of the children had no PK (67.6%), followed by moderate levels (24.8%), and high levels of PK (7.6%).

Results

Randomization check

We performed a randomization check for age, gender, and prior cartoon exposure. Prior cartoon exposure was assessed by asking children if they have seen the stimulus cartoon before participating in this study (50.5% yes; N = 105). Analysis revealed no significant differences between the three conditions (χ2 = 1.28; df = 2; N = 105; Φ = .11; p = .526). A randomization check for gender was also successful (χ2 = 1.37; df = 2; N = 105; Φ = .11; p = .504). With respect to age (M = 8.36; SD = 1.29), we also found no statistical differences between the conditions (F(2, 102) = 0.04; p = .964). Thus, no additional controls were included in the following analyses.

Manipulation check

Explicit measurement

We tested whether explicit disclosure memory of the children of the repeated disclosure condition was higher compared to the other experimental conditions. Immediately after the stimulus presentation, we showed the children a picture of a cutout of the stimuli showing the disclosure and asked them whether they had seen this sentence and symbol at the top of the screen (yes: 76.2%; N = 104; 1 missing value).

We conducted a logistic regression with disclosure memory (dummy coded: 1 = yes; 0 = no/other) as the dependent variable as well as the repeated disclosure condition as the reference group. Results indicated that the children in the no disclosure condition were significantly less likely to remember the disclosure compared to the repeated disclosure condition (b = –2.67; Exp(b) = 0.07; Wald χ2 = 10.81; p = .001). We also found that, compared to the repeated condition, in the one-time disclosure condition significantly fewer children indicated that they recognized a disclosure (b = –1.73; Exp(b) = 0.18; Wald χ2 = 4.42; p = .036). We thus deemed our manipulation check as successful.

In order that all experimental conditions got contrasted with each other, we also inserted the no disclosure condition as our reference group. With regard to the one-time disclosure condition, we only found marginal significant differences in comparison to the no disclosure condition (b = 0.94; Exp(b) = 2.56; Wald χ2 = 3.20; p = .074). Hence, a one-time disclosure at the beginning of the movie might not be enough to be manifested in children’s explicit memory. To ensure that this result could only be traced to the repetition of the disclosure and not an unbalanced processing of the disclosure at the beginning between the two disclosure groups, we also examined an implicit measurement. Hence, we tested whether disclosure repetition led to a greater processing of the cue on an implicit level.

Implicit measurement

For a manipulation check of children’s implicit processing of the disclosures, we defined each disclosure appearance as an AOI (coverage: 3.7%) and calculated dwell time. The movie included several frames containing disclosures. Each of these frames had a different duration but in total accounted for 6 seconds for each disclosure appearance. We standardized children’s dwell time by dividing their dwell time scores by the total exposure time for each frame. Afterward, we calculated mean indices for each disclosure appearance, which included the standardized dwell time scores of the related frames.

Regarding the disclosure at the beginning of the movie, we found no significant differences between the two disclosure conditions (n = 74; t(72) = –0.24, p = .810; repeated disclosure: M = .08, SD = .09; one-time disclosure: M = .09, SD = .13). When only considering the implicit processing of children in the repeated disclosure condition (n = 37), analysis of variance with repeated measures revealed that processing increased with each disclosure appearance (F(1.56, 56) = 7.10, p = .004; at the beginning: M = .08, SD = .09; after the commercial break: M = .15, SD = .18; at the end: M = .22, SD = .24). Hence, these results indicate that potential effects on the processing of the upcoming PP can indeed be traced back to the repetition of the disclosure.

Main analysis

Effects on visual attention toward the PP

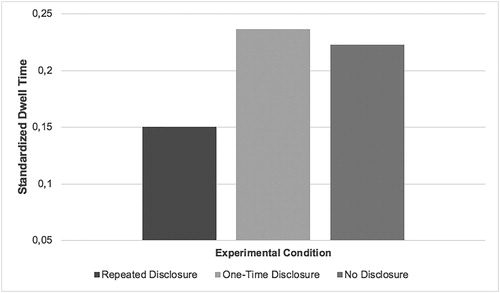

We first looked at the effects of the experimental condition on children’s visual attention toward the second PP (Hypothesis 1a, Hypothesis 1b) by conducting an ANOVA. We inserted the standardized dwell time scores for the second PP as the dependent variable and the experimental condition as the independent variable. Analysis showed a significant main effect of the experimental condition on children’s visual attention to the second PP, F(2, 102) = 3.92, p = .023, ηp2 = .071). Thus, the extent of children’s visual attention toward the PP at the second time of presentation differed between the conditions. As can be seen in , children who had seen the disclosure once (M = .24; SD = .17) and children who had seen no disclosure at all (M = .22; SD = .14) paid more visual attention to the PP compared to children in the repeated disclosure condition (M = .15; SD = .10).

Effects on the activation of PK

In order to test our whole conceptual model (see ) and to mirror the previous findings, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis using Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes Citation2013; model 14 using 5,000 bootstrapping samples). We mean-centered all continuous variables (i.e., age), inserted the repeated disclosure condition as our reference group and age as our moderator. We used the standardized dwell time of the second time of PP appearance as our mediator.

The results of the analysis showed that visual attention toward the subsequently presented PP was significantly higher when children saw a one-time disclosure compared to a repeated disclosure (b = 0.09; LLCI = 0.02; ULCI = 0.15). Furthermore, children paid significantly more visual attention to the PP in the control condition compared to the repeated disclosure condition (b = 0.07; LLCI = 0.00; ULCI = 0.14). Thus, a repeated disclosure did not lead to more (not supporting Hypothesis 1a) but instead to less (supporting Hypothesis 1b) visual attention toward the PP compared to a one-time disclosure and no disclosure.

Regarding PK, findings indicated a positive effect of visual attention toward the PP (b = 1.05; LLCI = 0.05; ULCI = 2.05). This lends support to Hypothesis 2. However, in contrast to our expectations (Hypothesis 3), age showed no moderating impact regarding the effect of visual attention toward the PP on PK (b = 0.16; LLCI = –0.44; ULCI = 0.75). Regarding Hypothesis 4, we also observed no direct effect of the experimental condition on PK (one-time disclosure condition: b = –0.05; LLCI = –0.34; ULCI = 0.24; control condition: b = –0.08; LLCI = –0.37; ULCI = 0.22). All findings are shown in .

Table 1. Moderated mediated analysis explaining persuasion knowledge.

In order that all experimental conditions were contrasted with each other, we ran a second analysis and inserted the disclosure condition as a reference group. With respect to visual attention to the upcoming PP, the results revealed no significant differences between the one-time disclosure condition and the control condition (b = 0.01; LLCI = –0.05; ULCI = 0.82). Regarding PK, we also observed no direct effect of the experimental condition on PK (repeated disclosure condition: b = 0.08; LLCI = –0.22; ULCI = 0.37; one-time disclosure condition: b = 0.03; LLCI = –0.26; ULCI = 0.32).

Given these findings, visual attention toward the subsequently presented PP of children in the repeated disclosure condition not only differed from the one-time disclosure condition but also from the control condition. Interestingly, there were no significant differences between the control condition and the one-time disclosure condition highlighting the difference of attentiveness potential between the two disclosure conditions. The results also showed that the higher children’s visual attention toward the placement the higher the likelihood that PK gets activated. We also revealed that disclosures did not directly lead to activation of PK. This result strengthens the key importance of the ongoing implicit cognitive activity (i.e., visual attention) while children receive PP when considering repeated disclosure effects.

In sum, the results revealed a significant negative indirect effect of disclosure repetition via visual attention on PK compared to the no disclosure condition (model 4; using 5,000 bootstrapping samples; repeated disclosure: b = –0.10; LLCI = –0.24; ULCI = –0.01) and compared to the one-time disclosure condition (model 4; using 5,000 bootstrapping samples; repeated disclosure: b = –0.12; LLCI = –0.25; ULCI = –0.02) with no moderating influence of age for the relationship between visual attention and PK.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that compared to a one-time disclosure and no disclosure, a repeated disclosure led to less visual attention toward the upcoming PP in children. When following theoretical explanations of priming, we suggest that a repeated disclosure triggered a reversed priming effect (Fransen and Fennis Citation2014; Laran, Dalton, and Andrade Citation2011). In other words, the repeated exposure to a disclosure led children to direct their attention away from the embedded brand. It is important to stress that the second PP was prominent (AOI coverage of 8.2%) and therewith alone already attracted visual attention. Additionally, since the control condition and the one-time disclosure condition did not differ in their attention, we can clearly interpret the pattern of the disclosure repetition group as avoidance. That is, had this group not seen the second disclosure, its pattern would be the same as for the control and the one-time disclosure condition.

We would propose that the reallocation of attention when being exposed to a repeated disclosure can be described as an unconscious process. That is, lower levels in visual attention also diminished children’s activation of PK. Hence, children were not able to explicitly state later on why they redirected their visual attention away from the brand. In turn, those who looked at the brand longer (children in the one-time disclosure and no disclosure condition) had higher levels of PK.

This points toward two different theoretical explanations of how children can be protected against persuasive influence. On the one hand, a repeated disclosure seems to automatically affect children by working as an implicit cue to direct their attention away from the upcoming embedded brands. When brands are not attentively processed, their persuasive power is obviously inhibited. In other words, repeated disclosures shield children against persuasive influence because they lead to an automatic avoidance of the processing of persuasive content. We call this the implicit strategy of protection against persuasion. This strategy does not require an explicit activation of PK since children tended to avoid persuasive messages already on an implicit level, when they were repetitively primed about them.

On the other hand, we consider PK as an explicit or conscious cognitive defense that requires active attention to the PP (Rozendaal et al. Citation2011). According to this view, attention to the brand is a necessary condition to shield children against persuasive influence. That is, only when children attentively process embedded advertising their PK can be activated. We call this the explicit strategy. In fact, we found no direct effect of disclosures on PK. This suggests that attention to the brand is necessary for PK to emerge (Boerman, van Reijmersdal, and Neijens Citation2015).

The key question is: Which path is deemed as more successful or helpful? Although additional studies are needed as a further validation, our findings underline, for the first time in extant research, the importance of the implicit strategy. In fact, research on the effectiveness of placements has pointed to implicit persuasion processes (e.g., Nairn and Fine Citation2008). This means viewers are influenced by PP without their conscious awareness. This perspective can also be used to understand the effects of disclosures. As implicit priming strategies require only a small amount of cognitive resources (Fransen and Fennis Citation2014) and the repeated exposure makes them more efficient, repeated disclosures can be a successful strategy to protect consumers against influence. Using implicit strategies might be particularly important when children are the target audience. That is, under conditions of low elaboration (Buijzen, van Reijmersdal, and Owen Citation2010), the PK in the form of a conscious cognitive defense may not be effective in reducing children’s susceptibility to embedded advertising (Rozendaal et al. Citation2011). Rephrased, in order to activate PK through effortful inferential thinking about the persuasive intent, sufficient cognitive resources are required by the audience. Such cognitive resources, however, are scarce and they are unlikely in the context of children watching highly arousing entertainment content (Nairn and Fine Citation2008).

Nevertheless, current literature in this field of research relies on the explicit strategy arguing that disclosing PP might help children actively use their PK (De Pauw, Hudders, and Cauberghe Citation2018; De Jans et al. Citation2018). Our results, however, do not underline the efficiency of an explicit strategy due to two reasons: First, disclosures did not directly lead to activation of PK in children but depended on their visual attention for the brand. Second, no disclosure and a one-time disclosure did not differ in the amount of visual attention for the PP, and hence, both equally led to the activation of PK. Furthermore, activation of PK overall was rather limited in our study with nearly 70% of all children showing no activation of PK at all. It follows that neither the embedded brand nor the existing disclosure at the beginning of the movie were successful at activating children’s explicit cognitive processing in the form of PK via more visual attention to the PP. Moreover, contrary to our expectations, age did not moderate the direct effect of visual attention toward the PP on children’s level of PK. Only the repetition of the existing disclosure provoked brand avoidance in children. This suggests that disclosure repetition is the key to helping children cope with embedded persuasive messages.

Limitations and future research

Given the fact that our study was the first investigating children’s cognitive processing of a repetitive disclosure, replications and other methodical approaches are highly encouraged. Most importantly, long-term effects might be especially interesting, because ‘priming tends to build long-term connections between a primed issue and the target through repetition’ (Sabbane, Bellavance, and Chebat Citation2009, 658). Future research is also encouraged to manipulate more levels of repetition frequency than the present study and to control for disclosure effects with an additional experimental condition including only a PP disclosure but no target brand. Particularly challenging is the question: at what point is repetition taken too far (van Reijmersdal, Neijens, and Smit Citation2009)? Furthermore, even though the inserted brand Utz is not a well-known brand in Austria, it has to be stressed that the brand is commonly present in the movie series ‘Alvin and the Chipmunks’. Therefore, disclosure effects may be different for completely unknown or even fictitious brands.

Moreover, our conceptual model solely tested children’s cognitive processing in this context. In line with other disclosure studies on children and adolescents (De Pauw, Hudders, and Cauberghe Citation2018), it might be interesting to extend the model by also investigating attitudinal components of PK (Rozendaal et al. Citation2011). In addition, the employed measurement of PK in our study is somewhat limited in its depth and response options. This was because we investigated children ranging from 6 to 11 years and the response options therefore had to be kept simple and short so that it was also understandable for the youngest participants (John Citation1999). However, examining a more narrow age range in the future would allow for a more extensive examination of PK.

Finally, concerning the missing moderating influence of age, other specific cognitive capabilities not tested here might be linked to PK. Since not only children’s ability but also the motivation to process a persuasive message indicates the depth of processing (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986), future research might also involve young viewers’ involvement as an important moderator when investigating PP disclosure effects.

Conclusion

Three main conclusions can be derived from our study. First, studies may fail to observe important effects of disclosures when using single, unrepeated manipulations. Second, we show for the first time in extant research that a repeated disclosure can unconsciously lead to brand avoidance, thereby also suppressing the activation of PK. We therefore propose that repetition of disclosures can serve the goal to shield children against persuasive influence. In this context, it is important to stress that avoidance prompted by repeated disclosures does not require high effort critical processing. Third, the findings of the present study are also inconsistent with the widely held belief of the ‘magic age’ (see Nairn and Fine Citation2008) in which children gain a fundamental understanding of the persuasive intent (John Citation1999). That is, independent of age, children who paid more visual attention to the PP were more able to correctly translate the persuasive message by explicitly recalling its persuasive attempts. However, we must keep in mind that overall, only few children showed moderate to high levels of PK. Therefore, age is not an indicator to predict if children between 6 and 11 years old understand the persuasive intent of embedded advertising.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Alice Binder, Sarah Ecklebe, Michaela Forrai, Helena Knupfer and Jennifer Jannasch, Melanie Saumer, and Lisa Woller for their tremendous help with conducting the study. Furthermore, we want to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and recommendations on our paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ines Spielvogel

Ines Spielvogel (MA, University of Vienna) is a junior researcher at the University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. Her research interests include persuasive communication as well as advertising effects on children and adolescents.

Brigitte Naderer

Brigitte Naderer (PhD, University of Vienna) is a senior researcher at the University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. Her research interests include persuasive communication, empirical methods, and advertising effects on children.

Jörg Matthes

Jörg Matthes (PhD, University of Zurich) is full professor of advertising research at the University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. His research interests include advertising effects, public opinion formation, and empirical methods.

References

- An, S., and S. Stern. 2011. Mitigating the effects of advergames on children. Journal of Advertising 40 no.1: 43–56.

- AVMSD Audiovisual Media Services Directive 2010. Directive 2010/13/EU of the European parliament and of the council accessed July 29, 2019. Retrieved from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32010L0013

- Balasubramanian, S.K., J.A. Karrh, and H. Patwardhan. 2006. Audience response to Brand placements. An integrative framework and future research agenda. Journal of Advertising 35 no.3: 115–41.

- Boerman, S.C., and E.A. van Reijmersdal. 2016. Informing consumers about hidden advertising. A literature review of the effects of disclosing sponsored content. In Advertising in new formats and media: Current research and implications for marketers, ed. P. de Pelsmacker, 115–46. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Boerman, S.C., E.A. van Reijmersdal, and P.C. Neijens. 2012. Sponsorship disclosure: Effects of duration on persuasion knowledge and Brand responses. Journal of Communication 62 no. 6: 1047–64.

- Boerman, S.C., E.A. van Reijmersdal, and P.C. Neijens. 2015. Using eye tracking to understand the effects of Brand placement disclosure types in television programs. Journal of Advertising 44 no. 3: 196–207.

- Buijzen, M., E.A. van Reijmersdal, and L.H. Owen. 2010. Introducing the PCMC model: an investigative framework for young people’s processing of commercialized media content. Communication Theory 20 no. 4: 427–50.

- Cain, R.M. 2011. Embedded advertising on television: Disclosure, deception, and free speech rights. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 30 no. 2: 226–38.

- Campbell, M.C., G.S. Mohr, and P.W.J. Verlegh. 2013. Can disclosures lead consumers to resist covert persuasion? the important roles of disclosure timing and type of response. Journal of Consumer Psychology 23 no. 4: 483–95.

- Daems, K., F. De Keyzer, P. De Pelsmacker, and I. Moons. 2019. Personalized and cued advertising aimed at children. Young Consumers 20 no. 2: 138–51.

- De Pauw, P.,. L. Hudders, and V. Cauberghe. 2018. Disclosing brand placement to young children. International Journal of Advertising 37 no. 4: 508–25.

- De Jans, S., I. Vanwesenbeeck, V. Cauberghe, L. Hudders, E. Rozendaal, and E.A. van Reijmersdal. 2018. The development and testing of a child-inspired advertising disclosure to alert children to digital and embedded advertising. Journal of Advertising 47 no. 3: 255–69.

- Dens, N., P. De Pelsmacker, and Y. Verhellen. 2018. Better together? Harnessing the power of Brand placement through program sponsorship messages. Journal of Business Research 83, 151–9.

- Folkvord, F., D.J. Anschütz, R.W. Wiers, and M. Buijzen. 2015. The role of attentional bias in the effect of food advertising on actual food intake among children. Appetite 84, 251–8.

- Fransen, M.L., and B.M. Fennis. 2014. Comparing the impact of explicit and implicit resistance induction strategies on message persuasiveness. Journal of Communication 64 no. 5: 915–34.

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research 21 no. 1: 1–31.

- Guo, F., G. Ye, V.G. Duffy, M. Li, and Y. Ding. 2018. Applying eye tracking and electroencephalography to evaluate the effects of placement disclosures on Brand responses. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 17 no. 6: 519–31.

- Hoy, M.G., and J.C. Andrews. 2004. Adherence of prime-time televised advertising disclosures to the “clear and conspicuous” standard: 1990 versus 2002. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 23 no. 2: 170–82.

- Hayes, A.F. 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Heath, R. 2000. Low involvement processing: a new model of brands and advertising. International Journal of Advertising 19 no. 3: 287–98.

- Hudders, L., P. De Pauw, V. Cauberghe, K. Panic, B. Zarouali, and E. Rozendaal. 2017. Shedding new light on how advertising literacy can affect children's processing of embedded advertising formats: a future research agenda. Journal of Advertising 46 no. 2: 333–49.

- Hudson, S., D. Hudson, and J. Peloza. 2008. Meet the parents: a parents’ perspective on product placement in children’s films. Journal of Business Ethics 80 no. 2: 289–304.

- John, D.R. 1999. Consumer socialization of children: a retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research 26 no. 3: 183–213.

- King, A. J. N. Bol, R. G. Cummins, and K. K. John. 2019. Improving visual behavior research in communication science: An overview, review, and reporting recommendations for using eye-tracking methods. Communication Methods and Measures : 1–29. doi:10.1080/19312458.2018.1558194.

- Kirkorian, H.L., D.R. Anderson, and R. Keen. 2012. Age differences in online processing of video: an eye movement study. Child Development 83 no. 2: 497–507.

- Laran, J., A.N. Dalton, and E.B. Andrade. 2011. The curious case of behavioral backlash: Why brands produce priming effects and slogans produce reverse priming effects. Journal of Consumer Research 37 no. 6: 999–1014.

- Matthes, J., and B. Naderer. 2016. Product placement disclosures: Exploring the moderating effect of placement frequency on brand responses via persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising 35 no. 2: 185–99.

- Matthes, J., C. Schemer, and W. Wirth. 2007. More than meets the eye. Investigating the hidden impact of Brand placements in television magazines. International Journal of Advertising 26 no. 4: 477–503.

- Naderer, B., J. Matthes, F. Marquart, and M. Mayrhofer. 2018. Children's attitudinal and behavioral reactions to product placements: Investigating the role of placement frequency, placement integration, and parental mediation. International Journal of Advertising 37 no. 2: 236–55.

- Naderer, B., J. Matthes, and I. Spielvogel. 2019. How brands appear in children's movies. A systematic content analysis of the past 25 years. International Journal of Advertising 38 no. 2: 237–57.

- Nairn, A., and C. Fine. 2008. Who’s messing with my mind? The implications of dual-process models for the ethics of advertising to children. International Journal of Advertising 27 no. 3: 447–70.

- Petty, R.E., and J.T. Cacioppo. 1986. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 19, 123–205.

- Piaget, J. 1929. The child’s conception of the world. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Roskos-Ewoldsen, D.R., B. Roskos-Ewoldsen, and F.R.D. Carpentier. 2002. Media priming: A synthesis. In Media effects: Advances in theory and research. ed. J. Bryant and D. Zillmann, 97–120. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Rozendaal, E., M.A. Lapierre, E.A. van Reijmersdal, and M. Buijzen. 2011. Reconsidering advertising literacy as a defense against advertising effects. Media Psychology 14 no. 4: 333–54. no.

- Sabbane, L.I., F. Bellavance, and J.C. Chebat. 2009. Recency versus repetition priming effects of cigarette warnings on nonsmoking teenagers: The moderating effects of cigarette‐Brand familiarity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 39 no. 3: 656–82.

- Smink, A.R., E.A. van Reijmersdal, and S.C. Boerman. 2017. Effects of brand placement disclosures: An eye tracking study into the effects of disclosures and the moderating role of brand familiarity. In Advances in advertising research VIII. ed. V. Zabkar and M. Eisend, 85–96. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

- Spielvogel, I., J. Matthes, B. Naderer, and K. Karsay. 2018. A treat for the eyes. An eye-tracking study on children's attention to unhealthy and healthy food cues in media content. Appetite 125, 63–71.

- van Reijmersdal, E.A., S.C. Boerman, M. Buijzen, and E. Rozendaal. 2017. This is advertising! Effects of disclosing television brand placement on adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46 no. 2: 328–42.

- van Reijmersdal, E.A., P. Neijens, and E.G. Smit. 2009. A new branch of advertising: Reviewing factors that influence reactions to product placement. Journal of Advertising Research 49 no. 4: 429–49.

- van Reijmersdal, E.A., E. Rozendaal, and M. Buijzen. 2012. Effects of prominence, involvement, and persuasion knowledge on children's cognitive and affective responses to advergames. Journal of Interactive Marketing 26 no. 1: 33–42. no.

- Vanwesenbeeck, I., S.J. Opree, and T. Smits. 2017. Can disclosures aid children’s recognition of TV and website advertising?. In Advances in advertising research VIII. ed. V. Zabkar and M. Eisend, 45–57. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

- Wright, P., M. Friestad, and D.M. Boush. 2005. The development of marketplace persuasion knowledge in children, adolescents, and young adults. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 24 no. 2: 222–33.