ABSTRACT

Research on how vulnerable consumers navigate various marketplaces and service interactions, developing specific consumer skills in order to empower themselves during such exchanges, has received inadequate attention. This paper contributes to this area by empirically drawing on a multi-perspective go-along travel study, consisting of a combination of in-depth interviews and observations of consumer and service provider interactions in mobility services. It addresses both factors that are a source of vulnerability and forms thereof during service interactions, thus unearthing critical mechanisms that explain why vulnerability comes into being. Further, the finding of four distinct forms of active coping strategies, building on the dimensions of proactiveness/reactiveness and explicit/implicit articulation, and how these are related to different forms of vulnerability, provides an understanding of coping with vulnerability during consumer and service provider interactions.

Introduction

Changing and improving the well-being of consumers has been receiving more and more attention from service research during recent years (e.g. Anderson & Ostrom, Citation2015; Anderson, Ostrom, & Bitner, Citation2011), and also been recognised as one of the most important research priorities (Ostrom et al., Citation2010; Ostrom, Parasuraman, Bowen, Patricio, & Voss, Citation2015). Transformative changes and improved well-being are particularly important for consumers who experience vulnerability, i.e. consumers who, for some reason, lack a degree of control and agency in consumption settings (Anderson et al., Citation2013; Hamilton, Dunnett, & Piacentini, Citation2015). Consumer vulnerability has been conceptualised as a temporary and fluid state of powerlessness (with specific populations being more at risk) accompanied by a strong emphasis on context-specific situations whereby the consumer lacks control and experiences an imbalance during marketplace interactions or due to the consumption of marketing messages and products (Baker, Gentry, & Rittenburg, Citation2005). As Baker et al. (Citation2005) argue, everyone has the potential to experience vulnerability; however, consumer vulnerability is not, for example, the same thing as dissatisfaction, or unmet needs, since other factors have to play a contributory role. The actual vulnerability ‘arises from the interaction of individual states, individual characteristics, and external conditions within a context where consumption goals may be hindered and the experience affects personal and social perceptions of the self’ (Baker et al., Citation2005, p. 134, italics in original). Vulnerability thus resides in the relationship between a person and a stimulus object, e.g. an interaction at a retail store or the consumption of a consumer good (Baker, Labarge, & Baker, Citation2015). If the relationship is damaged, this will affect consumer agency negatively.

The conceptualisation highlights the lack of control and the imbalance in the relationship in terms of being two key aspects of vulnerability. The lack of control relates to situations where consumers, due to limitations in their personal characteristics, states and/or external conditions, are particularly unable to control their surroundings, the environment, e.g. when service providers are insensitive to disabled consumers’ specific needs and limited own resources (Lee, Ozanne, & Hill, Citation1999), or when access to resources (e.g. health care, retail facilities, affordable products, public transport) is restricted (Baker et al., Citation2005). The imbalance experienced by the consumer can be related to something which, in previous research, has been conceptualised as a ‘power imbalance’ or ‘power asymmetry’ between service providers and their customers (e.g. Lee, Citation2010; Menon & Bansal, Citation2007; Price & Arnould, Citation1999), i.e. services (often professional or governmental) where customers experience the power being in favour of the service provider. This can involve services where the customer is highly dependent on the provider’s information, knowledge and judgement, or services where there are no alternatives for the customer (Lee, Citation2010).

A related, and broader, definition conceptualising consumer vulnerability in terms of ‘[…] an undesirable state catalysed by a number of human conditions and contexts’ has been put forward by Hamilton et al. (Citation2015, p. 1). Both conceptualisations highlight the interplay between the context and the conditions/characteristics of the individual consumer. Rather than being a permanent state (or a systemic class-based one, see Commuri & Ekici, Citation2008), vulnerability can thus be seen, in this view, as a situational experience that arises during marketplace interactions.

Despite the recognition of interaction as a key concept and a contextual aspect of consumer vulnerability, few studies have examined vulnerability in detail in relation to actual service interactions between consumers and service providers. There is also a general tendency in the marketing literature on vulnerability to overlook consumers with disabilities (Kaufman–Scarborough, Citation2015; Pavia & Mason, Citation2014), something that is somewhat surprising since these people are more ‘at risk’ of being harmed (Baker et al., Citation2015). One exception to this, even though these scholars did not focus specifically on vulnerability, is Baker, Holland, and Kaufman-Scarborough (Citation2007), who found that the interaction between the servicescape characteristics (store staff, the in-store environment, other customers and the product/service range) and shoppers’ personal characteristics (different disabilities) influences their assessment of the environment in terms of being either enabling or disabling.

Dunnett, Hamilton, and Piacentini (Citation2016) specifically highlight the need to study the ways in which vulnerable consumers navigate various marketplaces and service interactions, developing specific consumer skills in order to empower themselves during such exchanges. One such area is how consumers with different forms of disability cope with their vulnerability in service settings. Coping during day-to-day activities has been found to be crucial for their subjective well-being (Maes, Leventhal, & de Ridder, Citation1996; Pavia & Mason, Citation2004). However, how these coping strategies used in service settings can be classified and explained, in relation to the different forms of vulnerability experienced, has not been addressed. This article aims to contribute to these issues. In order to achieve this aim, we use empirical data on consumers with different forms of disability who interact with mobility service providers in order to carry out the activities of their day-to-day lives. Using the mobility service, consumers encounter particular situations where they experience vulnerability in the form of dependence, powerlessness and a reduced capacity to act, which are harmful to their sense of well-being and have negative ramifications for their identity. The service chosen for the study is also characterised by a power imbalance on the customer side, which is due to the fact that these customers are highly dependent on their providers and the fact that there are no alternative services available to them. We define dependency, in accordance with Wilkin (Citation1987, p. 868, italics in original), in terms of being a ‘state in which an individual is reliant upon other(s) for assistance in meeting recognised needs’.

The paper contributes in several ways to both research and practice concerning consumer vulnerability in service settings. It addresses factors that contribute towards forms of vulnerability during service interactions, thus unearthing critical mechanisms that explain why vulnerability comes into being. Further, the finding that there are four distinct forms of active coping strategies, building on the dimensions of proactiveness/reactiveness and explicit/implicit articulation, and how these are related to different forms of vulnerability, provides more explanations about coping with vulnerability during consumer and service provider interactions.

The paper continues with a short discussion about the vagueness of the current definitions of vulnerability and suggests an alternative definition. This is followed by an overview of coping as a theoretical concept and of previous research into the active strategies used by consumers with different forms of disability, who experience vulnerability when navigating various marketplaces. We then account for our research design, i.e. using a combination of interviews and observations in order to unearth the causes, forms and coping strategies used by consumers during service interactions. The findings are then presented and discussed before the conclusions and contributions made by the study are summarised.

Literature review

Vulnerability

Vulnerability, as defined in the literature, is something that everyone can experience during their lifetime (Baker et al., Citation2005; Elms & Tinson, Citation2012; Falchetti, Ponchio, & Botelho, Citation2016; Pavia & Mason, Citation2014; Rosenbaum, Seger-Guttmann, & Giraldo, Citation2017; Schultz & Holbrook, Citation2009). In order for someone to experience vulnerability, a certain set of criteria need to be in place. Marginalised, discriminated against, or stigmatised groups in society match these criteria well, making them more prone to experiencing vulnerability (Baker et al., Citation2015).

However, the literature lacks some clarity in terms of defining what vulnerability is all about. One of the main references, followed by many others, is Baker et al. (Citation2005) who provide a comprehensive definition that includes quite a lot of components, summing up most of the criteria and factors to be found in the literature. Other researchers who follow Baker et al., in essence, directly use (or reformulate) single or combinatory elements of this somewhat vague definition, not clearly defining the meaning of, and the relations between, the inherent components, e.g. the lack of control, the dependence and the power imbalance.

We take the standpoint that consumer vulnerability is primarily a state of powerlessness that occurs in consumption settings when a consumer has to deal with a certain set of limiting external consumption conditions in such a way that these negatively affect his/her persona, social self-perception and consumption goals. To this ‘core’ part of the definition, we would add that this state of powerlessness will typically be reinforced if the individual consumer is negatively affected by certain individual characteristics and states. This definition of vulnerability is stringent enough and makes us sensitive when examining the ‘essence’ of vulnerability.

Coping with vulnerability

Coping has been described as the cognitive and behavioural efforts and resources used by individuals to deal with the internal and/or external demands created by situations of threat, harm and loss (e.g. Fleming, Baum, & Singer, Citation1984; Folkman, Citation1984; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984; Terry, Citation1994). Distinctions have been made between two general categories of coping: emotion-focused coping, aimed at reducing or managing the negative emotions associated with stressful events (e.g. avoidance, distancing, seeking emotional support), and problem-focused coping, aimed at the cause of the problem, removing/evading it or diminishing its negative effects (e.g. planning, taking direct action, seeking assistance) (Carver & Connor-Smith, Citation2010; Carver, Scheier, & Weintraub, Citation1989; Folkman, Citation1984; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984). These two coping categories have also been described as complementary and interrelated, rather than distinct and independent (Lazarus, Citation2006). Effective problem-focused coping can diminish the threat, and thus also the distress associated with it, while effective emotion-focused coping can diminish distress and make a person think more calmly, thus generating, perhaps, a better kind of problem-focused coping (Carver & Connor-Smith, Citation2010). There is also some research which focuses on coping and which is aimed at preventing threatening situations from arising in the first place. Such proactive coping (Aspinwall & Taylor, Citation1997) is almost always problem-focused; the resources accumulated can form strategies used to prevent threats from arising or growing (Carver & Connor-Smith, Citation2010).

However, some researchers argue that this distinction between the more ‘active’ (problem-focused) and the more ‘passive’ (emotion-focused) forms of coping can be problematic when applied to those in more vulnerable positions since the distinction suggests that vulnerable consumers may be more prone to using emotion-focused coping, which is regarded as less instrumental and thus less effective (Hutton, Citation2016, p. 254). As described by Baker et al. (Citation2005, see also Adkins & Haeran, Citation2010; Banyard, Citation1995; Hobfoll, Dunahoo, Porath, & Monnier, Citation1994; Lee, Ozanne, & Hill, Citation1999; McKeage, Crosby, & Rittenburg, Citation2018, for instance), consumers who experience vulnerability are not just passive recipients of the bad things that come their way. They may just as well be active, instrumentally acting in relation to different forms of vulnerability.

Research has highlighted a number of active strategies used by consumers with different forms of disability who experience vulnerability when navigating various marketplaces. Such strategies include how the disabled use the Internet to avoid the ‘impracticalities’ of shopping in physical retail stores (Elms & Tinson, Citation2012); how families with disabled children adapt in order to meet marketplace challenges (seeking stores with open floor plans), adapt with regard to family roles and norms (dividing work) and adapt with regard to rituals and family identity (changing family diets) (Mason & Pavia, Citation2006); how individuals with auditory disorders choose between physical servicescapes, opt for electronic devices and e-servicescapes and delegate shopping to relatives when exposed to sensory overload in servicescapes (Beudaert, Gorge, & Herbert, Citation2017); and how visually impaired consumers seek social and instrumental support from their family and friends (Balabanis, Mitchell, Bruce, & Riefler, Citation2012; Falchetti et al., Citation2016; Matsunaka, Inoue, & Miyata, Citation2002; Reinhardt, Citation2001), either choosing consumption locations, payment methods and products/services that are appropriate to their needs and perceived as simpler (Falchetti et al., Citation2016) or choosing to carry on as if they were not disabled (Baker, Stephens, & Hill, Citation2001). As shown by Baker et al. (Citation2001), consumers with disabilities can also respond and adapt to the marketplace in terms of independence and dependency. In their study of visually impaired consumers, they propose a model whereby independence and dependence sometimes co-occur, being determined by environmental factors (physical, logistical and interpersonal ones), personal characteristics (perceived adaptation skill and ability), perceived cost (in social, psychological and financial terms) and the level of comfort when asking for and using assistance. Independence during marketplace decisions can, for example, be attained with the assistance of store employees in retrieving information or getting products down from shelves. Assistance that is given despite being unwarranted, inappropriate or undesirable is described as imposed dependency by Baker et al. (Citation2001). An attempt by a presumably well-meaning employee to help a consumer with a disability can be perceived as infantilisation when, for example, that employee provides help that is neither needed nor desired, speaks only to the person accompanying the disabled consumer or decides where the consumer should sit because of his/her disability. Situations whereby the disabled are ignored or treated as incapable of doing or deciding things lead to, or enhance, the vulnerability experienced.

Thus, previous research has provided insights into how consumers with different forms of disabilities cope with their vulnerability in difficult marketplace settings; however, less is known about their coping with vulnerability during direct interactions with service provider employees (Dunnett et al., Citation2016). This lack of research is also noticeable in studies focusing on disabled consumers’ travel. Here, research has predominantly concerned consumers’ satisfaction and needs when travelling (Denson, Citation2000; Hine & Mitchell, Citation2001; Wasfi, Steinmetz-Wood, & Levinson, Citation2016), accessibility and barriers to travel (Lindahl, Citation2008; Risser, Haindl, & Ståhl, Citation2010; Wennberg, Hydén, & Ståhl, Citation2010), exclusion from society (Church, Frost, & Sullivan, Citation2000; Iwarsson & Ståhl, Citation2003), safety when travelling (Wretstrand, Citation2007; Wretstrand, Petzäll, & Ståhl, Citation2004; Wretstrand, Ståhl, & Petzäll, Citation2008) or how particular disabilities, special medical conditions or certain ages (usually concerning the elderly) impact travel (Levin et al., Citation2007; Risser, Iwarsson, & Ståhl, Citation2012).

Coping strategies during interactions are likely crucial both to the consumer experience and to the development of the marketing practices of service providers. Direct interactions between the consumer and the service provider have been recognised as especially important since these may have both a positive (value creation) and a negative (value destruction) impact on the consumer (cf. Echeverri & Skålén, Citation2011; Grönroos, Citation2011). During interactions with consumers, organisations also have the opportunity to influence (and control) the service process (Grönroos, Citation2007; Schneider & Bowen, Citation1995).

Methodology

To explore vulnerability and coping strategies during service interactions in more depth, from a consumer perspective, a qualitative single-case and ethnographically inspired methodology was used, with a multi-perspective approach to interviews and observations. This approach has been deemed especially appropriate for the in-depth analysis of service encounter interactions (Arnould, Citation1998) and for uncovering nuances in the interactions (Miles & Huberman, Citation2004). This combination of interview and observation also allows researchers to distinguish between perceived and actual vulnerability (Baker et al., Citation2005). This approach obtains open and detailed answers from the informants, as well as a nuanced understanding of what is important to them, given their context.

Data collection

For our analysis, we (two researchers) used a dataset from the mobility service for disabled individuals. We conducted multiple in-depth semi-structured interviews with 11 consumers (6 women and 5 men) with a wide range of disabilities. In-depth semi-structured interviews enable access to rich, contextual data and also allow the flexibility to further explore topics arising during the interviews (Miles & Huberman, Citation2004). The disabilities identified by the informants included chronic pain, the effects of a stroke, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, sensitivity to infections, visual impairment, physical impairment, difficulty handling unfamiliar situations and people, memory problems and difficulty handling stress and orienting oneself outdoors. The age of the informants ranged from 28 to 94. The purposes of their journeys included mundane things like shopping, visiting relatives and friends, going to the cinema or theatre, engaging in other types of social activity or going to the doctor/dentist/pharmacy.

Our dataset is based on a go-along approach. First, we interviewed consumers at home, grasping the important contextual factors, e.g. their disabilities and how these affect them in their day-to-day lives, their life situations and interests, their personal needs and experiences in relation to the mobility service and their interactions with drivers. Then, we accompanied them on journeys, using the mobility service, to one or two destinations which the consumers themselves had chosen. During these journeys, we continued with the interviews, encouraging them to comment on a wide range of issues experienced while using this service. This was done on the basis of our interest in understanding their perceptions, thoughts and meanings in connection with using this service. Accompanying disabled consumers in shopping situations, or when they are using different services, has proven itself to be appropriate in previous studies examining, for example, accessibility (e.g. Kaufman–Scarborough, Citation1999). Our participation in the journeys was approved by the mobility service organisation, and the drivers were informed of our role as independent researchers.

During the journeys, we also took field notes and photos, and made audio recordings, documenting crucial situations and interactions, e.g. interactive behaviours between consumers and drivers, their demeanour, their use of equipment, information exchange, etc. We completed the interviews at the destination, asking the consumers to reflect on things that had happened, the drivers’ performance, the consumers’ role in the service process and how they had personally experienced it in relation to their functional limitations (positive/negative/indifferent). Using this in situ procedure, we were able to unearth contextually relevant factors and to get access to naturally occurring data that we deemed important for gaining an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon (cf. Silverman, Citation2006). Each go-along interaction with a consumer lasted for about 2 h.

In order to get an in-depth understanding of the service per se, we also studied the service provider side (drivers handling the mobility service process) of things. We accompanied four other drivers, with each journey lasting between 1.5 and 2 h, in more or less the same way as the consumers, applying the go-along approach and data collection in the field (semi-structured interviews and observations), in their natural environment. The drivers were asked to drive to different locations illustrating different aspects of their work. During the journey, and at these locations, they described their work in general and how they interact with the consumers in both everyday situations and in situations which work especially well, or which do not work well. No consumers were present during these journeys. Five interviews were also conducted, each lasting between 1 and 1.5 h, with other drivers at the mobility service office. The interviews with the consumers and the drivers were digitally recorded (audio) and then transcribed.

As in all research, conducting participant observations risks having an impact on the interactions you are studying. However, we tried to minimise this risk by conducting initial interviews with the informants prior to the observations. Here, we clarified our research interest and our independent role in relation to the mobility service organisation. We also stated that the study would be anonymised. We believe that this made the informants feel more at ease, and more prone to act as they usually did in these situations. In addition, the questions we posed during the observations formed a natural part of our conversations with them. Our aim was for this to provide us with their narratives regarding how they usually act.

Then, we went ‘undercover’; i.e. one of the researchers took on the role of a person using a wheelchair, while the other acted as his personal assistant. Over the course of 10 journeys (each lasting between 15 and 45 min), journeys which had been approved by the mobility service organisation, we made detailed observations of the service procedure, taking field notes and photos (using an iPad and a smartphone). This technique is close to mystery shopping observations; i.e. a concealed form of participant observation where actors act as consumers or potential customers in order to study the processes and procedures used during service delivery (Wilson, Citation1998). For several decades, this has been widely used in retail, healthcare, hospitality and other B2C service sectors in order to evaluate intangible service experiences (Ford, Latham, & Lennox, Citation2011). Participant observations can provide richer knowledge of the experiential nature of services; the technique can also ensure that the experience is natural and not contrived for the sake of the observer (Wilson, Citation1998). The technique raises ethical issues, i.e. observing people without their consent. Besides gaining the approval of the mobility organisation to conduct these observations, the drivers had also been made aware that observations could take place – but not when. In fact, the mobility service organisation regularly conducts such observations itself for quality assurance reasons. At the same time, as discussed in the literature (e.g. Jorgensen, Citation1989; Wilson, Citation1998), services are often performed in settings where employees are being observed by other consumers. Being observed as an employee can thus be seen as a normal, everyday circumstance.

The findings mainly relate to go-along observations, and to the individual interviews with consumers and drivers. Using the introspection approach of ‘undercover’ observations made us more sensitive in our interpretation of what goes on during the procedure, and as regards the contextual cues, physical objects and equipment used in the service. Another argument for this kind of data collection is the possibility of better being able to concentrate on the actual interaction between ourselves and the service provider – i.e. specific physical/manual procedures, looks, facial expressions, mimicry, body positions, which are all modalities constituting important elements of the production of the consumer experience.

Finally, we discussed our findings with representatives of the service-providing organisation, in order to further understand the background prerequisites and organisational limitations of service performance in general. Throughout the study, we acted with the organisation’s permission, but as independent researchers. We decided what was of interest to the study and had no obligation to report any of our results to the organisation. We deemed our independence important when it came to gaining the trust of the informants. How to approach and study consumers in an ethical way was thoroughly discussed with the service-providing organisation, which also assisted us during the sampling process and in gaining access to the informants. We informed the organisation that we wanted variation in terms of gender, age, disability (among the consumers) and number of years in the job (among the drivers). The organisation contacted the consumers and asked them if they wanted to participate in a research study being conducted by independent researchers. The consumers were assured that their participation was voluntary that they could choose to leave the study at any time, and that their names and the information they provided would be anonymised. We repeated this information when subsequently contacting those who had agreed to participate. All the participants gave us permission to do both interviews and go-alongs. The study was conducted in Southwest Sweden.

These rich and empirically grounded descriptions give us access to information about the relevant factors of this phenomenon, putting us in a position where we can provide more in-depth and valid explanations of which forms of vulnerability consumers experience and how they cope with these forms of vulnerability. We argue that this in situ research approach has greater merits when it comes to exploring this phenomenon than the more commonly used data collecting methods found in service research, especially methods such as (literature-driven) a-priori-defined consumer surveys and interviews.

Data analysis

The empirical data was coded and we detected empirical categories, themes and variables capable of informing our key research questions. More to the point, sensitivity to the vulnerability of the consumer segment, as well as how different coping strategies are realised during service encounter interactions, guided our joint collection and analysis of data. The constant comparison of narratives made us sensitive to the things that were of key importance to the participants.

Empirical codes, which are either in vivo codes or simple descriptive phrases, were used; our joint collection and analysis of data ended when we experienced theoretical saturation (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). In the main, the data were coded non-prejudicially, i.e. without a-priori coding schemes (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998).

Initial codes were clustered into emerging categories with regard to (1) forms of vulnerability experienced, (2) factors contributing to vulnerability, (3) proactive and reactive coping strategies and (4) the explicit and implicit clarifying of needs. In order to further increase the possibility of obtaining credible results, we used triangulation in the form of two different ‘investigators’ (see Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Both authors examined the data individually and discussed the analysis jointly. Finally, iterative reflections upon the empirical material contributed to the conceptualisations made in the article. The categories, illustrated with quotes in the ‘Findings’ section, are not simply the perceptions of one informant, as others in the sample felt the same way.

Findings

This section is divided into three parts: Firstly, we characterise the specific mobility service that the consumers are referring to, and the role it plays for them. This provides the context-specific aspects necessary for understanding what is going on during interactions. Secondly, we specifically describe the forms of vulnerability experienced during service interactions with providers, and the factors contributing to vulnerability. Thirdly, we describe consumers’ proactive and reactive coping vis-à-vis the needs they express, both explicitly and implicitly, to the service providers – needs that are related to their various forms of vulnerability.

The mobility service and its role regarding the consumer

The mobility service is provided by the municipality where the consumers live. Consumers who have disabilities hindering their mobility (e.g. paralysis, multiple sclerosis, vision impairment/blindness) to the extent that they cannot, without great difficulty, use regular public transport, can apply for a permit to use this service. The service is largely funded through taxation, with consumers paying a fare for each journey that equals the cost of using regular public transport.

In terms of choice of travel mode for these consumers, no other municipal or privately owned forms of mobility service are available. This lack of service options can, as described in previous research (e.g. Baker et al., Citation2005), contribute to vulnerability. Also, the number of mobility service journeys that consumers can make every month is limited, with these journeys most often including picking up other consumers who are going to other places, meaning that there is no certainty (compared to a public transport timetable) as regards when the vehicle will arrive at the destination. The mobility service thus has inherent limitations that make it less flexible and more uncertain than public transport.

The drivers and their organisation work on the basis that they are serving consumers with different forms of disabilities, and whose health and well-being can change at any time during the day. Often, a journey needs to be booked days in advance and some consumers’ health and overall sense of well-being may have taken a turn for the worse on the day of travel, or once they have done their errands. The lack of service options, and the consumers’ characteristics (in terms of disabilities and health), structures this relationship in an imbalanced way.

However, this imbalance is not absolute. The drivers have the authority to adapt to the consumers’ wishes and requests if this be beneficial to the consumers, and reasonable and doable in view of the situation, and as long as this does not endanger the safety of the consumers or entail any negative consequences for the other consumers using this service. Driver training includes the general aspects of being service-minded, friendly, helpful, etc., but importantly also aspects of flexibility in such service situations. The drivers have the authority to act differently to what their ‘instructions’ call for, and there will not be any negative consequences if they use their common sense and act in accordance with the situation. In general, the drivers characterise their work as being quite stressful. They have a tight schedule in terms of the time available for picking up the consumers and driving them to their destinations. All of the drivers are specially recruited for the task, based on their social competence. They are all required to both speak and understand Swedish, although some of them have a foreign background. Most of the consumers are native Swedes.

All the interviewed consumers use the mobility service on a regular basis and generally regard it to be an important part of their daily lives and activities. They provide two main reasons for this: The first is that the service has positive implications for their physical well-being. Using this service enables them to both conserve physical energy, and thus manage to do more during their day, and reduce the pain caused by their disabilities when having to rely on public transport.

Fibromyalgia means I’m in chronic pain. I’m always somewhere between 3 and 10 on the pain scale. So sometimes I’m bedridden with pain, sometimes I’m more mobile. I also experience excessive fatigue, insomnia and so on. No matter how much I sleep, I’m always tired, and everything I do, it’s kind of like having to prepare myself for a marathon race. That means that I can’t ride on the tram very often. […] The bumping around [on the tram] causes me more pain, it spreads up into my back. Then, if it takes an ordinary person 5 minutes to walk to the tram stop, it takes me 20–30 minutes, taking breaks in between. That’s why I use this mobility service, because I’ll have more energy. When I use this service, I don’t have to rest that much. (Female, aged 28)

The second reason described by the consumers is that the service provides a sense of freedom to move around and to do things they either like or need to do, not to mention being less dependent on the help and goodwill of relatives and friends.

If I didn’t have the mobility service, then I’d have been stuck here [at home], dependent on my mum to drive me to different places. Now I’m not nearly as dependent on my mother. I feel good about not being in a position of dependence. Being able to move around, to go places. And if I want to go home, then I don’t need to say to her: ‘Can you take me home now?’ (Female, aged 41)

Besides this consumer perspective, the public transport authority, in its role of ultimately being responsible for the mobility service, this independence in mobility brings mental and, to some degree also, physical health to the consumer, at least in the long run. As a consequence, it is possible to reduce unnecessary care dependencies and, in turn, societal costs regarding healthcare. This is also mirrored in the drivers’ avoidance of providing assistance when this is not necessary. This ambiguity, as regards when to help the consumer and when to avoid it, is a salient characteristic of the mobility service and an important background factor in understanding the providers’ operations.

Forms of vulnerability experienced and interactional factors

Although having a generally positive view of the mobility service, the consumers also highlight situations when they experience vulnerability based on the interactions between themselves and the service providers. It is during these interactions that vulnerability emerges and is addressed. Three different principal forms of experiencing vulnerability are identified during these interactions: physical discomfort, commodification and disorientation. These are described in what follows, together with nine factors relating to consumer and service provider interactions which contribute to vulnerability.

Physical discomfort

The first principal form of experiencing vulnerability is in situations whereby consumers become car sick, feel increased pain or become more tired, i.e. experiencing situations that affect their physical well-being in a negative way, labelled physical discomfort in this context. Three different factors contribute to this form of vulnerability: (1) Driving style, i.e. drivers do not sufficiently adapt their driving to consumers’ specific needs, driving in a fast and jerky manner, not slowing down enough on bends or choosing roads that are bumpy, have a lot of bends or are badly maintained; (2) Management of ambient conditions, i.e. drivers choose to have the temperature set too cold/hot in their vehicles; or (3) Embodied action, i.e. drivers do not provide enough physical help to/from vehicles, or with bags. The last point is often based on instructions issued by the mobility service itself, i.e. whether or not consumers have requested help with their bags. If consumers have not mentioned needing help with their bags when booking a journey, then some drivers may refuse to help even though they have the authority to be flexible. Physical discomfort, as a distinct form of vulnerability, is shown in the following quote from a consumer, describing a situation whereby the driver had not adapted his driving style to this consumer’s specific needs:

Well, there was one … I don’t know how old he was, barely 30, worked for [name of the taxi company], and had his foot firmly on the accelerator. […] He liked driving fast and furious. It doesn’t feel nice when you’re going downhill in [name of the town] at 100–110 km/h, over those speed bumps … and when you’re sick already and on your way to the doctor’s. It’s not pleasant at all. (Male, aged 44)

Commodification

The second principal form of experiencing vulnerability includes situations whereby consumers feel like ‘commodity items’, i.e. are treated in an insensitive and objectified way, with their sense of self, self-worth, integrity and capabilities being compromised. This is the experience of being dehumanised, of not asking for ‘permission’ to act in a certain way, here labelled commodification – i.e. being treated as an object, rather than a human being. This form of vulnerability clearly stands out in the data where quotes indicate how consumers are overlooked and treated in a slightly nonchalant manner. Similarly, three different factors contribute to this form of vulnerability: (1) Attitude, i.e. drivers not sufficiently respecting consumers’ abilities, and wishes, to do and decide things for themselves; (2) Approaching, i.e. drivers acting superior or nonchalant; or (3) Addressing, i.e. drivers not speaking to consumers directly and instead putting direct questions, information, etc. to the assistants, relatives or friends accompanying them. The first-mentioned factor, attitude, is more common than the other two and includes situations whereby drivers put seatbelts on consumers without asking whether they can or want to do this by themselves. One consumer describes this kind of situation thus:

I find it difficult when they [the drivers] do things without my permission. They try to put my seatbelt on, or something … I’m too proud to admit that I have a disability, so I try to do things for myself as far as I can. It’s annoying when they do things that I can do myself, because I think they have no business doing that. (Female, aged 28)

The quote illustrates situations of unsolicited assistance negatively affecting the consumer, in the sense of being overlooked as a human being capable of doing things for him-/herself. The experience of commodification also shows itself in the way that providers approach consumers. One example, driven by the ‘clash’ between drivers’ instructions and the needs of the consumer, is the consumer’s seating location within the vehicle. Some consumers express a need to sit in a certain seat because this makes the journey more comfortable and reduces the risk of them becoming tired or sick. Again, drivers have the option to be flexible if the situation allows that. Drivers who do not let consumers themselves decide where to sit (if this is not necessary) often communicate this in a nonchalant manner. One consumer describes a situation illustrating this way of approaching:

It’s not that I demand to sit in the front seat, but I do ask … and then he [the driver] starts yelling at me straight away: “It says here [points at the driver’s information display unit] that you’re supposed to sit in the back seat.” And then I say: “Well, that’s just a … it’s just that I feel pretty bad.” And then he thinks I’m annoying. (Female, aged 41)

The third factor, addressing, shows itself in different ways. An elderly and visually impaired female described a general sense of being objectified, how she sometimes feels like a ‘commodity’ being bluntly shipped from one point to another, indicating that the actual physical and communicational treatment of the consumer is insensitive to the human and emotional side of the personal interaction:

You feel a bit like a commodity. That sense … at least when it comes to some drivers. In some sense it’s true … But you sometimes get that feeling. (Female, aged 64)

Disorientation

The third principal form of experiencing vulnerability includes situations whereby consumers feel resigned, being unable to control their surroundings, the physical environment, due to service providers not being sensitive to their spatial needs, here labelled ‘disorientation’. The identified factors contributing to disorientation are as follows: (1) Navigation, i.e. drivers cannot locate the right address or, from the consumer’s perspective, choose the wrong route, leading to consumers not knowing when they will arrive and/or where they will be dropped off; (2) Coordinating, i.e. drivers do not say anything about additional consumers being picked up during the journey, leading to other consumers not knowing when they will arrive; and (3) Assisting, i.e. drivers do not leave their vehicles to assist consumers, who thus do not know whether or not they will have to make it on their own to/from the vehicle.

One consumer, with a visual impairment, addresses the navigation factor in the following quote, i.e. the need to be dropped off at the right spot, at the right address, from where she knows which way to walk:

Well, it depends on the driver [if all goes well]. It’s almost like a lottery. It’s worse if they can’t find the address. […] Then you get irritated. […] There are lots [of drivers] who aren’t from round here, and who haven’t been living in Sweden so long. (Female, aged 94)

Another consumer describes the need to be informed of whether or not there are other consumers to be dropped off/picked up, i.e. a sense of being coordinated with other travellers.

Some [drivers] don’t say a word. And if I’m about to travel with other people [consumers], which is almost always the case, then it’d be very nice if the driver said where we were going to pick up those people. They don’t always do that and then you just sit there like a package, more or less. And there are lot of … blind people who don’t know where they’ll be going then. (Female, aged 64)

Finally, the way the consumers are spatially assisted is addressed under this disorientation label, as in the following quote, where a visually impaired female talks about her need to get some assistance to the vehicle:

A good driver doesn’t stay in his vehicle. On one occasion, he [the driver] sat parked on the other side of the street, not on my side where I live. It was a beautiful day and I was sitting in my garden waiting for the car. And for 20 minutes, he was sitting in his car looking at me. And he didn’t get out of it. And finally, he called out, “If you don’t come now, I’ll leave.” But I didn’t even know he was there. […] There was sign saying ‘mobility service’ on the car, he pointed it out, but I couldn’t see it [she has a visual impairment]. […] I think it’s bad that they don’t bother to get out of the car and open the door as they’re supposed to do. (Female, aged 94)

Proactive and reactive coping strategies

The previously described forms of experiencing vulnerability, i.e. different aspects of powerlessness, allow consumers to develop active strategies to cope with the negative aspects of the service situation. During the inductive analysis of the consumer narratives, a wide range of strategies were detected, and each related to aspects of powerlessness. These strategies were clustered within 10 distinctive categories. All of them address a time dimension, i.e. when actions are taken, before or after a harmful incident. We label these strategies as either ‘proactive’ or ‘reactive’. The former prevents a potentially negative incident while the latter mitigates it. Both are grounded in the procedural knowledge of the consumers and thus possible to foresee or react to. But all these strategies also receive a structure, some form of articulation. Some are expressed clearly by the consumers (often verbally), while others are expressed more vaguely (often non-verbally). Why is this the case? We understand this as a way of regulating the interaction in an appropriate way. We label these strategies either ‘explicit articulation’ or ‘implicit articulation’. The former provides reasons for consumer needs which directly inform the concrete service procedure, while the latter more vaguely indicates aspects of human attitude, reasons for specific consumer needs. These two dimensions allow us to distinguish between four principal forms of active coping strategies. How these four coping strategies work in relation to experiencing vulnerability is described in what follows, where examples illustrate the situations described by the consumers.

Proactive and explicit articulation

This coping strategy includes situations where consumers interact with service providers in order to prevent situations of vulnerability from arising in the first place, and where they explicitly articulate the reasons for this in terms of specific needs.

Two forms of proactive and explicitly articulated coping sub-strategies are identified with both being related to consumers’ vulnerability manifested as physical discomfort. The first form concerns how to act in relation to providers’ core delivery. In this context, it includes driving issues, such as when consumers ask drivers to drive carefully and not too fast since they would otherwise become car sick or experience more pain. The second form deals with consumers’ co-action. This includes situations concerning consumers’ seating locations inside the vehicle, e.g. when they inform drivers that they want to sit in a particular seat inside the vehicle (usually the front seat) due to the risk of becoming car sick or experiencing increased levels of pain during the journey, or increased pain when trying to move from outside the vehicle into other seats inside the vehicle (usually the back seat). An example of the second form of coping can be seen in the following quote:

I had been to a dinner and was going home, and when I got to the vehicle, I said to the driver: “I’d like to sit in the front seat … because I’ve just eaten. Even though I haven’t eaten so much I sometimes get sick afterwards”. I know that if I’m sitting in the back of the car, and he drives jerkily, and then maybe he’ll have to stop the car because … (Female, aged 41)

Proactive and implicit articulation

This type of coping strategy is also aimed at preventing vulnerability, but is conducted in an implicit manner. Consumers try to accomplish this without clearly expressing to drivers the actual reasons for their needs in order to avoid sharing potentially sensitive information (e.g. relating to their disabilities), to avoid situations where they could be perceived as dependent or less competent or to avoid situations where drivers get upset.

Three forms of proactive and implicit coping sub-strategies are identified, each relating to a specific form of vulnerability. The first form is consumer informing. This relates to physical discomfort and includes situations whereby consumers give directions regarding which way to drive in order to avoid bumpy roads and shorten journey times, which could otherwise result in discomfort such as pain and car sickness. The second form, preventing disrespect, relates to consumers’ vulnerability manifested as commodification and includes situations whereby consumers, who want to do things and make decisions for themselves, tell drivers they can put on their seatbelts themselves, or that they want to sit on a particular seat in the vehicle. This is done in order to prevent situations whereby drivers do not respect consumers’ ability and desire to do things and make decisions for themselves. The third form, ascertaining service duration, relates to disorientation and includes situations whereby consumers, in order to avoid any uncertainty concerning how long the journey will take, or whether or not they will be able to get to the door once they have arrived at their destinations, ask the drivers if they will pick up other consumers or instruct them to drop consumers off at a particular place. One consumer describes how she acts in order to avoid uncertainty regarding journey times:

When I’ve gotten into the vehicle, I ask [the driver]: “Are any more people going with us or not?” Then they usually answer. It’s very nice to know this. (Female, aged 28)

Reactive and explicit articulation

Yet another type of coping strategy is when consumers reactively deal with situations in order to mitigate the vulnerability which they have experienced and which has already emerged, while clarifying the reasons for this on the basis of their needs.

Two forms of reactive and explicit coping sub-strategies are identified and both of these relate to consumers’ vulnerability manifested as physical discomfort. The first form is tempering bodily inconvenience and includes situations whereby consumers, during their journeys, ask drivers to slowdown because they are experiencing pain or feeling sick. The second form deals with how to moderate ambient conditions and includes situations whereby consumers ask drivers to turn on/off the heating/AC, while explicitly stating that they are feeling too hot or cold. The following quote illustrates the first form of coping:

Usually, I’m very good at saying: “Don’t drive so fast and jerkily. Drive slower because I feel sick.” I often say that. (Female, aged 28)

Reactive and implicit articulation

Finally, coping strategies can be reactive and implicit. Consumers react in situations whereby they experience vulnerability, but they do not explicitly state the reasons for their needs. Three forms of reactive and implicit sub-strategies are identified. The first form, insinuating discomfort, is related to consumers’ vulnerability manifested as physical discomfort. It includes situations whereby consumers get tired, or experience pain, due to carrying their bags to/from the vehicle or due to how drivers drive, commenting on the weight of these bags or making themselves noticed through paralinguistic respiration, e.g. a sigh, grunt, gasp or throat-clearing, or through interjections, small ‘non-words’, such as ‘ouch!’, ‘oops!’ or ‘oh-oh!’. An example of the last two is illustrated in the following consumer quote:

I was travelling to the hospital and had a real headache. Wasn’t well at all. The driver was driving fast and quite carelessly, but I didn’t feel like starting an argument with him about how to drive. Didn’t have the energy to explain … tell him why I wanted him to go slower. Instead, I made discrete noises on curves and sighed noticeably when he accelerated fast or braked suddenly. This seemed to work after a while [as he drove slower]. I’ve noticed that some drivers don’t like it when I tell them to drive more carefully. (Male, aged 44)

A second form relates to commodification and includes situations whereby consumers implicitly indicate that the driver is violating their integrity, e.g. when a consumer raises his/her voice to gain the driver’s attention. This can occur when a driver, instead of talking directly to a consumer, asks the consumer’s assistant if he/she wants to sit on a certain seat inside the vehicle. As with the insinuating discomfort quote, this is also an example of paralanguage use, in this case vocal amplitude. It is a form of communication that can nuance meaning or convey emotions. We label this indicating disrespect, and it is illustrated in the following quote:

He [the driver] didn’t talk to me. Instead, he turned to my assistant … He ignored me. I tried to talk louder. (Male, aged 44)

The third form, indicating uncertainty, relates to disorientation and includes situations whereby consumers, at the very moment they begin or end their journeys, experience uncertainty regarding an uneven and/or slippery surface, an inconvenient curb position, a slope or weather conditions. Consumers’ reactions in these situations include asking (without referring to disabilities) the driver to help them get to the vehicle or to move the vehicle to a better place for the drop-off. The underlying reasons (their disabilities) are only implicitly expressed to their drivers. One elderly female with visual impairment describes a typical situation:

I experienced my porch steps as slippery and asked the driver to meet me. There are some small steps down from my porch, only six … But I’m ashamed to say that the rocks in my garden path are laid a bit unevenly … I know they’re there but I’m afraid of stumbling on them so I think … It’s much better if they [drivers] come and get me at my door. But I don’t feel comfortable to always tell them about my disability. It’s to private. (Female, aged 94)

Thus, all these reactive and implicit coping strategies are used by consumers instead of articulating the underlying reason for their discomfort. Instead, consumers make indirect comments using irony, humorous metaphors, understatements or non-verbal communication which disguise what drivers may otherwise interpret as criticism or as a sign of consumers’ ‘weakness’ and dependency (due to their disability). As was also illustrated, consumers sometimes do not want to articulate the reasons for their discomfort because they feel that their health prevents this – i.e. they lack the energy needed.

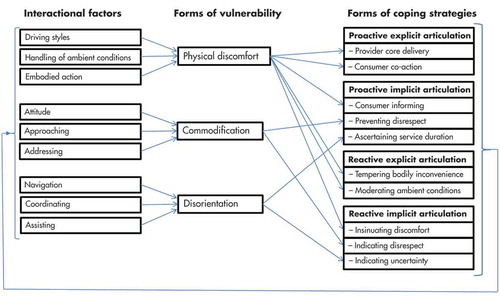

In summary, as shown in this ‘Findings’ section, the study identifies three principal forms of vulnerability, i.e. physical discomfort, commodification and disorientation, which consumers may experience. These are explained by nine influential interactional factors, relating to consumer and service provider interaction. The graphical model (see ) illustrates an empirical pattern of clustered factors, with each cluster relating to a specific form of vulnerability. The three forms of vulnerability are in turn addressed by consumers using four main classes of coping strategies reflecting forms of proactiveness/reactiveness, regarding consumer approach, and explicitness/implicitness, regarding articulation. These classes cover 10 sub-strategies which can in turn influence the interactional factors. The key linkages articulate the main mechanisms of vulnerability inductively identified in the study.

Discussion

Few previous studies have examined in detail how consumers, who are more prone to experiencing vulnerability, cope with service interactions (Kaufman–Scarborough, Citation2015; Pavia & Mason, Citation2014). Here, we will discuss some of the findings, comment on the main linkages between the inherent elements and the dynamics of a shifting power imbalance during service interaction and reflect on how the study contributes to research.

In their seminal paper about consumer vulnerability, Baker et al. (Citation2005) proposed consumer–provider interactions, under certain conditions, as one of several contextual factors that can contribute to consumer vulnerability; however, they did not elaborate on what contributes to vulnerability during consumer–provider interactions. Later vulnerability studies have also overlooked this aspect. As shown in our study of disabled travellers, we unearth nine different interactional factors that explain the existence of three principal forms of negatively experienced vulnerability, a specific sense of powerlessness. The character of the identified factors indicates that vulnerability can emerge during all parts of consumer–driver interactions. How drivers drive, handle ambient conditions, assist consumers and navigate, as well as drivers’ attitudes and how they approach and address their consumers, all affect consumers in terms of physical discomfort, commodification and disorientation. This reflects the power imbalance in this kind of service (e.g. Lee, Citation2010; Menon & Bansal, Citation2007; Price & Arnould, Citation1999), i.e. that customers are highly dependent on providers’ information, knowledge and actions.

Further, previous research has characterised vulnerability as a state of powerlessness, a term reflecting a high level of dependence, lack of control and a reduced capacity to act (Baker, Citation2009; Baker et al., Citation2005, Citation2007; Lee et al., Citation1999). Our study confirms this but we argue that there are substantial abilities to influence it and, in so doing, to regulate the power imbalance (level of dependence, amount of control) between the actors. The consumer’s ability to deal with the service situation is damaged, but not necessarily to the degree that he/she is prevented from acting at all. For example, visually impaired consumers might more easily be able to navigate their way home if drivers stop on demand at a specific street location in line with consumer preferences. Therefore, we suggest that it is more relevant to understand power balance as shifting (not only a stable, asymmetric state), and to view dependence as relative to independence, while viewing control as relative to the possibilities of exercising it, rather than a definite category. Although these structure the actual service interaction, they are also mutually influenced by the actual interaction, a kind of structure-action interdependence.

The study identifies three forms of vulnerability that emerge during consumer–provider interactions. The fact that physical discomfort is of key importance is not so surprising. Bodily impairment and illness have an impact on consumers’ mobility, as reported in existing research, both being conditions that consumers have to deal with. Physical disability is the reason for using the service in the first place. But what stands out in our findings is the centrality of commodification and disorientation. These forms of vulnerability have not been reported in previous research. They illustrate that there is something in the actual interaction between the consumer and the service provider that entails negative implications for the consumer’s sense of self-worth, integrity and capabilities, or the ability to control his/her surroundings. These subtle aspects seem to be as important as physical discomfort. Commodification is the disrespectful objectification of the individual, treating the customer as an object with no feelings and no will. This is close to what Baker et al. (Citation2001) call ‘infantilising a person’ or ‘viewing [someone] as less than an adult’, but more strongly connotes a non-human aspect, while disorientation displays a situation where a disabled person feels spatially confused or ignored.

Our findings regarding four principal forms of coping strategies, i.e. combinations of proactive/reactive and explicit/implicit strategies during interactions with providers – and how these strategies relate to different forms of vulnerability – enrich research on how disabled consumers cope with vulnerability. Previous research has only studied coping on the broader, more aggregated marketplace level, e.g. how disabled consumers avoid the impracticalities of shopping in physical retail stores (Elms & Tinson, Citation2012), seek social and instrumental support from their families and friends when shopping (Balabanis et al., Citation2012; Falchetti et al., Citation2016; Matsunaka et al., Citation2002; Reinhardt, Citation2001) or choose payment methods and products/services that are perceived as simpler (Falchetti et al., Citation2016). These studies provide important results regarding how disabled consumers cope in different marketplaces, but offer little explanation for the resources used during actual consumer–provider interactions. Our study contributes to this. In particular, the finding of explicit and implicit coping strategies suggests that marketplace interactions between consumers and providers contain conflicting needs that consumers have to deal with. They need to prevent or mitigate vulnerability while at the same time balancing it against how they want to be perceived in relation to the service provider.

As shown in , the linkages differ between aspects of vulnerability and the different coping strategies. For instance, concerning physical discomfort, the study shows that all four principal forms of coping strategies are used by consumers in order to prevent or mitigate this form of vulnerability. Why is this? One explanation is the profound impact that the physical aspect has on consumer well-being, that consumers will do ‘anything’ to avoid it. Driver training also centres on serving consumers that have different forms of physical disabilities. In situations of experiencing commodification or disorientation, consumers also use proactive and reactive strategies, but only implicitly. When consumers only express the reasons for their needs implicitly, and especially with reference to commodification and disorientation, we interpret this as a conflict between needs. Consumers want to prevent or mitigate vulnerability, but being explicit as regards reasons can damage their relationship with the driver, i.e. expressing needs that risk being interpreted as criticism by him/her.

Expressing needs implicitly can also be seen in terms of consumers wanting to be perceived as more independent, and wanting to do things for themselves, while simultaneously being highly dependent on their providers. This corroborates findings by Baker et al. (Citation2001), i.e. that disabled consumers can simultaneously be dependent and independent during specific service interactions. The will to act can be related to the concept of consumer normalcy, e.g. that consumers want to demonstrate competence and control, and to be perceived as equals in the marketplace (Baker, Citation2006). Having someone else deciding and doing things for you risks triggering a feeling of being marginalised, of not being listened to, or of not being perceived as competent (cf. Kaufman–Scarborough, Citation2015). Wanting to be perceived as independent, and not creating tensions vis-à-vis drivers, thus explains why consumers engage in this form of deliberate, ‘active’ concealment of the vulnerability they experience. The perceived emotional and social costs may be too high (Baker et al., Citation2001). In addition, having a disability can also be viewed as something highly personal and, as Baker, Stephens and Hill (Citation2002) describe it, not an appropriate discussion topic for the marketplace. We add to this research field by explaining why this dependence is a reality in relation to a specific set of interactional factors, and how it is addressed by the consumer in terms of a specific set of coping strategies. In particular, our findings regarding implicit articulation as a coping strategy add to the framework of Baker et al. (Citation2001) concerning how disabled consumers’ independence and dependency are manifested in the marketplace. The use of implicit articulation explains how consumers seek to regulate the balance between independence and dependency. In comparison to the framework of Baker et al. (Citation2001), we also explicate the interpersonal environmental factors, called interactional factors in our , which determine disabled consumers’ responses to the marketplace in terms of their independence and dependency.

Further, we also interpret the use of implicit strategies as a consequence of a remaining and unconscious insensitivity, on the part of the provider, to consumers’ experience of being objectified and disoriented, which is subtly displayed in drivers’ attitudes; an aspect too sensitive to be explicated by consumers during service procedures. However, in some cases, drivers informed us that the avoidance of assisting consumers, when perceived as unnecessary, was a conscious approach, for the sake of the consumers’ health. This idea is based on the conception that it is good for the consumer to be active and to do things on his/her own initiative during service procedures. Thus, there is a kind of ambiguity here regarding who does what, and when. In that sense, the interaction, including the power balance and concrete role behaviour, is negotiated by the participants and displayed, on the consumer side, in the identified set of coping strategies. Coping in situations of commodification also offers an explanation as to why consumers act in situations that include what Baker et al. (Citation2001) refer to as imposed dependency, i.e. when the assistance given, in this case by drivers, is unwarranted, inappropriate or undesirable.

Also illustrated in is a link between forms of coping and interactional factors, reflecting the dynamics of the power balance. At different points during the service process, the provider (driver) needs to involve the consumer in order to provide detailed information on requirements, specific arrangements, or specific needs. At these points, the consumer actively adds to the process and influences the service procedure, typically in terms of increasing the service provision flow. However, the consumer may also, as shown in this study, proactively or reactively add to the process, taking the initiative as regards dealing with the vulnerability experienced. In a sense, the consumer co-creates the service, with the power balance between the two shifting, alternating between them. Thus, at different points during the process, the two actors negotiate on the basis of situational contingencies, on who has the power, and the study unearths how the consumer regulates this by using the different forms of coping strategies. This finding also adds to research on vulnerability.

Finally, some comments on the dark side of the service that we have studied. Besides the positive aspects, e.g. enabling consumers to save energy and to experience a sense of freedom, the service can also be counter-productive, reinforcing the sense of helplessness and ‘otherness’ felt by the consumers. Service providers (drivers) who act indifferently or uninterestedly towards their consumers, or are not aware of their needs, risk causing permanent feeling of being vulnerable. However, this may not only be related to individual drivers’ characteristics, but also inherent limitations existing on the service system level. The drivers work on a tight schedule in terms of the time available for picking up consumers and driving them to their destinations, causing stress among the drivers which limits their ability to provide a good service. In addition, and similar to what has been put forward in previous research on public transport (e.g. Enquist, Johnson, & Camén, Citation2005; Fellesson, Salomonson, & Åberg, Citation2013), the nature of the mobility service contains elements of a ‘production logic’ as it demands a level of large-scale efficiency and standardisation, with a tendency to develop pre-planned and comparatively inflexible operations. This inhibits demands for individualisation, flexibility and adaptability, demands which, for example, risk further enhancing consumers’ feelings of being treated like ‘commodities’. Therefore, despite the mobility service organisation’s aim of providing a service that respects its consumers’ needs, there are complexities in the service system that indirectly affect consumer vulnerability. The organisation needs to be aware that its aim of creating a service that is based on ‘consumer care’ can instead be interpreted, through the providers’ actions, as ‘commodified care’ by the consumers.

Conclusions and contributions

This study centres on understanding which forms of vulnerability consumers experience during service situations, and on how consumers employ active coping strategies that help them during these situations of experiencing vulnerability. We thus address recent calls for research into how consumers experience and cope with vulnerability during service situations, especially during interactions between consumers and service providers (Dunnett et al., Citation2016; Ostrom et al., Citation2015). By focusing on the vulnerability of disabled consumers, we also address a section of the marketing literature that has received comparatively little attention (Kaufman–Scarborough, Citation2015; Pavia & Mason, Citation2014). Our findings are based on interviews and observational data obtained from consumers with different forms of disability, who use the mobility service in order to carry out the activities of their day-to-day lives.

Existing research has shown that groups more prone to experiencing vulnerability are exposed to the greater perceived risks associated with consumption. In our study, three particular risks stand out: i.e. the risk of experiencing physical discomfort, the risk of being treated as a commodity and the risk of being disoriented. Our study shows, however, that consumers have a range of resources with which they can handle these risks – i.e. a number of coping strategies. Thus, dealing with vulnerable consumers is not only a matter of designing appropriate service procedures but it is also a matter of what the consumer adds to the encounter. With the help of coping strategies, consumers, in conjunction with service interactions, can provide themselves with an ability to handle a range of problematic internal (individual constraints) and external situation-specific conditions (external conditions), resulting in them being able to compensate for the power imbalance associated with consumption. This insight is valuable both to the consumers themselves and to those who provide the services. On the supplier side, this means that managers can give front-line employees greater autonomy in relation to organisational instructions regarding how to behave during service encounters. An increased level of authorisation to assess different situations, e.g. dilemmas between conflicting organisational policies, during certain service interactions, should be encouraged.

The study specifically contributes to research in three ways: Firstly, by means of addressing interactional factors influencing vulnerability, and forms of vulnerability during service interactions, we unearth the critical mechanisms explaining why vulnerability arises during service interactions. In comparison with previous research (e.g. Baker et al., Citation2002; Balabanis et al., Citation2012; Elms & Tinson, Citation2012; Falchetti et al., Citation2016; Mason & Pavia, Citation2006; Matsunaka et al., Citation2002; Reinhardt, Citation2001), the study provides more detailed explanations of vulnerability during service situations, especially situations whereby the consumer interacts with a service employee. The three major forms of vulnerability identified, i.e. physical discomfort, commodification and disorientation, are grounded in consumers’ interactions with their service providers, and in the fact that these consumers need to rely on their providers’ knowledge, skill and willingness to provide the help that they need. Service providers who do not sufficiently adapt to their consumers’ specific needs in different situations can cause these consumers to experience vulnerability.

Secondly, the study provides an understanding of four distinct forms of active coping strategies: proactive and explicit articulation; proactive and implicit articulation; reactive and explicit articulation; and reactive and implicit articulation. We term these strategies proactive and reactive in order to indicate that they either prevent vulnerability (proactive) or mitigate emerged vulnerability (reactive), and as explicit and implicit in order to indicate that the consumer either articulates to the service provider what his/her vulnerability consists of (i.e. explicit) or tries to achieve the same results concerning his/her vulnerability without expressing the underlying reasons for his/her needs (i.e. implicit). While previous research tends to focus on discrete forms of coping (e.g. seeking support from family/friends or choosing alternative ways of shopping), our findings reveal a more complex pattern of coping strategies. The mobility service enables consumers to become more independent, but this service includes situations where consumers are highly dependent on the service provider. This dependence is especially accentuated in situations where vulnerability is experienced. Coping regulates the balance between consumers’ independence and dependence while at the same time handling their relationships with service providers, including the emotional and social costs of interacting. The study also adds to research in terms of not viewing consumers who experience vulnerability simply as passive recipients, but as potentially active and instrumental recipients in relation to different forms of vulnerability (see Adkins & Haeran, Citation2010; Baker et al., Citation2005; Banyard, Citation1995; Hobfoll, Dunahoo, Ben-Porath, & Monnier, Citation1994; Lee et al., Citation1999; McKeage, Crosby, & Rittenburg, Citation2018). The palette of coping strategies found in this study thus offers a more empowering perspective on disabled consumers’ activities with regard to research on consumer vulnerability, giving them a clearer role as co-creators during service encounters. This less asymmetric perspective contrasts with the earlier dependency discourses often associated with disability studies.

Thirdly, we provide a theoretical understanding of how vulnerability is related to the principal forms of active coping strategies. The consumers thus use these strategies to prevent or mitigate the effects of vulnerability, especially when it comes to physical discomfort, which has such a pervasively negative effect on their well-being. Not feeling well, or being at risk of experiencing this, triggers consumers into reactively or proactively, explicitly or implicitly, expressing their needs to the service provider. Commodification and disorientation do not trigger nearly as many different forms of coping strategy as physical discomfort. Nevertheless, our study shows that experiencing commodification and disorientation is handled using proactive and reactive strategies, but only in an implicit way. This finding contributes to the understanding that certain forms of vulnerability, forms which are more related to consumers’ sense of self and their control over the situation, can be handled by means of consumers not expressing the actual cause of their need to the service provider. Some situations are sensitive in terms of integrity, and the fact that consumers do not want to offend service providers by telling them how to do their job.

In addition, the study also has some managerial implications. Not only should service providers rely on asking (or even guessing) what the needs of their consumers are, or how to act in respect of these needs, they should also rely on the resources and coping strategies that consumers use during service interactions. Consumers provide information about this both proactively and reactively, articulating it explicitly and implicitly in various ways. Being sensitive to this information will solve a wide range of interactional problems. Employee training can thus include interaction techniques by which employees learn to interpret the subtler signals given by consumers. Adopting a more resource-sensitive approach can enable service providers to reduce, or avoid, the creation of power imbalances in exchange contexts (Lee et al., Citation1999).

To conclude, the value of conducting this study is both theoretical and practical. Theoretically, it unearths crucial mechanisms that explain in more depth the realisation of service and well-being in consumer vulnerability contexts. As such, it specifically adds to the transformative service research literature in its endeavour to empirically shed light on an overlooked and socially important service research field. The practical side includes fresh insights into how consumers actually cope with experiencing vulnerability and which interactional factors influence this coping. These insights provide service providers with conceptual tools for understanding how to better adapt to or comply with consumers.