ABSTRACT

Small rural schools have often been characterised as being at the heart of their communities. However, there is no clarity on what that means nor on the perceived meaning of ‘community’ within this context. The findings of the Small School Rural Community Study focused on the relationship between small rural schools and the communities they serve within the post-conflict context of Northern Ireland’s religiously divided schooling system. Using survey data and qualitatively derived data from this three-year study, we explore the ways in which community is understood and conceptualised by school principals, staff, parents, pupils and community members, in five case study areas. Similarly to another research study, our findings suggest that community can be conceptualised as having four key dimensions: people; meanings; practices; and spaces. The study found that a range of ‘community practices’ happened in school and around school, and that these practices had attached meanings, with schools helping to develop a sense of belonging and pride in the community, sometimes even a sense of ‘shared space’. Drawing on these key dimensions, the paper provides a theoretical framework of ‘community’ to expand our understanding of school-community relations and the potential value of small rural schools beyond simply the educational.

Introduction

Many rural schools worldwide face the prospect of closure because of large migration waves to urban areas coupled with metrocentric policies striving for economic efficiency (Cedering & Wihlborg, Citation2020; Corbett & Tinkham, Citation2014; Moreno-Pinillos, Citation2022; Villa & Knutas, Citation2020). For those opposed to this policy trajectory, a key reason given for these schools to remain open is the detrimental impact that their closure would have on the communities they serve. Indeed, rural schools have been viewed as able to create a positive sense of identity and belonging (Sörlin, Citation2005); develop and maintain beneficial social capital (Autti & Hyry-Beihammer, Citation2014; Bagley & Hillyard, Citation2014); enhance the local economy (Halsey, Citation2011); and act as the ‘social glue’ that keeps the local community together (Kearns et al., Citation2010). However, what is understood and meant by ‘community’ when framed and used in these ways in relation to rural schools remains largely undeveloped. Moreover, insofar as the notion of inter-ethno-religious community relations are central to peace and reconciliation in Northern Ireland’s continuing divided and segregated society, the need for further research and deeper conceptual engagement is particularly salient and important. The findings from the Small Rural School Community Study presented in the paper, following Liepins’ (Citation2000) conceptual framework, report the ways in which community is understood and conceptualised in five contrasting case study schools in Northern Ireland.

Divided rural communities

After years of political conflict, Northern Ireland’s society has traditionally (and perhaps simplistically) been divided along ethno-religious and political lines between two main groups: a group with an Irish political/cultural identity and a Catholic background, inclined to strive for a united island of Ireland; and a group with a British political/cultural identity and a Protestant background, prone to support the status quo of Northern Ireland being part of the United Kingdom. These ethno-religious political identities continue to be reproduced at every level of society including where people choose to live (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency [NISRA], Citation2011). At all levels of society, constructs are fostered within families and communities, and are reinforced through structures and institutions, which are often mutually exclusive (McCully & Clarke, Citation2016).

Traditionally, rural communities in Northern Ireland have been characterised by sectarian silences and tensions (Harris, Citation1972). Moreover, as Shortall and Shucksmith (Citation2001) observed, Protestant and Catholic communities in rural areas often live separate and distinct lives with two types of schools, two types of youth clubs, two churches and different religious events/practices/rituals, two community groups, etc. Shared spaces are scarce, and places are tied up with politics and identity, where people do not use the one that does not ‘belong’ to their ‘own’ community. This lack of ‘shared spaces’ reduces potential interactions between the two groups. On the other hand, in small rural communities, familiarity (i.e. everyone knows everyone) means that everyone can ‘tell’ someone’s community background (Hamilton et al., Citation2008). Indeed, in the context of Northern Ireland (urban and rural), the declaration of the place one lives, alongside one’s name and school they attended, is used as a proxy to determine (and avoid asking directly) an individual’s religion (Leonard, Citation2009).

Rural schools within a religiously divided schooling system

In 2021/22, 55% of all 796 primary schools in Northern Ireland were classified as rural schools, and 39% of these rural schools had less than 100 pupils (170 of 435) (DE, Citation2022). Just like its society, the schooling system in Northern Ireland is divided along ethno-religious lines. The two dominant types of primary schools are mostly attended by either pupils with a Protestant background (Controlled schools) or by pupils with a Catholic background (Catholic Maintained schools). As shown in , in the school year 2021/22, less than one per cent of pupils in Catholic Maintained primary schools had a Protestant background and just eight per cent of pupils in Controlled primary schools had a Catholic background. There are also a small number of Integrated schools, which are attended by pupils of both religious denominations, other religions or none.

Table 1. Primary schools (PS) in NI and their pupils’ background (year 2021/22).

Many initiatives have been designed to compensate for this divided system and improve cross-community relationships. A crucial one, which started as contact programmes between pupils in Protestant and Catholic schools in the 1980s, has more recently taken the form of school collaborations and been named Shared Education. The Shared Education Act (NI) 2016 embedded sharing within the Northern Ireland education system. Through shared education programmes, pupils continue to attend their own schools but participate in joint classes and activities with pupils from other types of schools. However, despite general evidence of positive outcomes of shared education (Borooah & Knox, Citation2013; Hughes et al., Citation2012; Loader & Hughes, Citation2017a), some studies have shown that it does not necessarily lead to more meaningful cross-community contact between pupils from the two backgrounds (Loader, Citation2022; Loader & Hughes, Citation2017b). In the next section, we turn to the methods and theoretical framework underpinning the study followed by our findings and concluding discussion.

Methods and theoretical frame

The Small School Rural Community study focused on the relationship between small rural schools in Northern Ireland and the communities they serve within a divided schooling system. In positioning school-community relations as a two-way process, the study asked: what is the role of small rural schools in their communities? How do they serve the community in which they are situated and how do rural communities affect small schools’ dynamics and shape the schools’ circumstances and characteristics?

The study adopted a two-part mixed method explanatory sequential approach (Edmonds & Kennedy, Citation2017), with data being collected in two phases to allow for in-depth insight into a particular social phenomenon. The first phase consisted of an online survey of all principals of small rural schools in Northern Ireland to explore the relationship between small rural schools, parents and families, other schools, the wider community and policy organisations. The overall findings of the survey have been reported elsewhere (Fargas-Malet & Bagley, Citation2023). In this paper, we draw on the survey findings to help contextualise and situate the subsequent qualitative findings from the case study phase of the research, seeking to investigate in greater analytical depth the relationships initially referenced in the survey between schools and their communities. In particular, we report on the survey findings related to descriptions of the community the school serves; those community organisations deemed most influential by the school; the ways schools engaged with the local community; and participation in shared education programmes. The case study schools were identified through purposive sampling (Schatzman & Strauss, Citation1973) from those responding small school principals that agreed to participate. The key characteristics used to identify the schools were school type, school size (number of pupils), and geographical area. We aimed to select two Controlled schools, two Catholic Maintained schools and one Integrated school, with a range of pupil numbers and across Northern Ireland. We considered these characteristics to be particularly relevant within the context of Northern Ireland’s divided schooling system. The case studies included school and community visits, with the principal acting as the key gatekeeper (Walford, Citation2001) for the identification of other participants.Footnote1 For each case study school, we interviewed the principal; two other staff members (i.e. teachers, administrative staff and classroom assistants); parents (in focus groups of between two and four; one focus group per school); and members of the Board of Governors. All the interviews and focus groups lasted approximately 60 minutes. We also conducted class discussions with pupils (aged between 8 and 11 years old), specifically on the concept of ‘community’ and their school. In line with a child-centred and directed approach to doing research with children (Driessnack, Citation2006), the work with pupils included a draw-and-tell technique. After the class discussion, children were provided with drawing materials and asked to draw what ‘came to mind’ when they were asked about their communities, and the researchers then asked them, one by one, to tell her about their drawings. Their brief responses were recorded and kept together with their drawings. This child-centred technique was deemed to be of particular importance given the relative lack of attention paid to the voice of the rural child, certainly in UK and European based educational studies (Fargas-Malet & Bagley, Citation2022). Some of the children’s quotes in the class discussions, their drawings and descriptions are used to illustrate the pupils’ perspectives on their school and communities.

Results from the survey were analysed through descriptive statistics using SPSS software. The qualitative data from the case studies was digitally recorded, transcribed and analysed thematically using NVivo software. We did an initial coding exercise, with common themes and sub-themes emerging from all the types of participants in the different schools (e.g. advantages of small schools as an overarching theme, and ‘family-like’ environment as sub-theme). The themes identified were then merged with Liepins’ (Citation2000) key dimensions of community, as they blended naturally into that framework.

Ethical approval was sought and granted by the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work in Queen’s University Belfast, where the research took place. All participants gave informed consent.

Sample

Our definition of small rural schools is based on the policy and administrative context of the region. In this study, ‘small’ refers to the number of pupils enrolled. In particular, the ‘small’ benchmark was determined by the 2019 Department of Education Sustainable Schools policy, which established that primary schools in rural areas should have at least 105 pupils enrolled. Despite acknowledging the complexity of the notion of ‘rurality’, we outlined our ‘rural’ criteria using the Northern Ireland administrative definition, in particular the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency’s (NISRA, Citation2015) definition of ‘rural’ areas as settlements with a population of less than 5,000 and areas of open countryside. This is also the definition that the Department of Education uses when classifying schools (as either rural or urban) in their records available online.

To sum up, our research included all primary schools in rural areas in Northern Ireland that had 105 pupils or fewer enrolled. Initially, we identified these schools with records for the school year 2019/20, when 198 schools fitted our criteria. However, two schools had closed by the end of that year, resulting in 196 schools left. Subsequently, data became available for the school year 2020/21. In that year, five schools had decreased their enrolment numbers to have 105 pupils or fewer enrolled. In addition, ten schools had an increase of pupils enrolled surpassing such number. We decided to keep these ten schools, which still had fewer than 116 pupils enrolled and add the five that newly matched our criteria. Invitations to complete an online questionnaire were sent to the principals of 201 small rural schools. Of these, 91 participated in the survey, although five of them did not fully complete it. This corresponds to a response rate of 43%, which is deemed good for an online survey (Dillman et al., Citation2014), especially one conducted during the Covid-19 pandemic. The online questionnaire mostly consisted of multiple-choice questions and an optional open text box for any further comment. Fifty principals wrote in the open text box and ticked another box agreeing to be contacted regards the possibility of participating in the case-study aspect of the research. From these 50, a purposive sample of five case studies, across four of the five counties of Northern Ireland, were identified for qualitative research. The schools’ geographic and social contexts were considerably diverse. Some (i.e. Killyloch, Aghreah and Carryhill) were in townlands surrounded by farmland and others (i.e. St Mary’s and Mullabally) in villages of different sizes. One was located near a large urban area on one side and the border with the Republic of Ireland on the other side. The schools also differed in terms of size, although four of them were considerably small (less than 50 pupils enrolled). describes some of the schools’ characteristics. The schools and their townlands or villages were given pseudonyms.

Table 2. Case study schools’ characteristics.

Theoretical framework

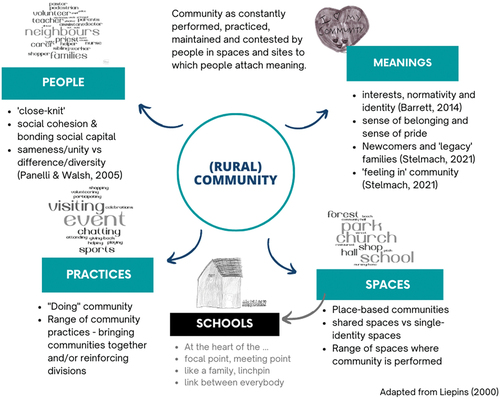

In order to explore the notion of ‘community’ in small rural schools, the study used a theoretical framework to make sense of the quantitative and qualitative data. The primary analytical basis of this framework follows Liepins’ (Citation2000) key dimensions of community, i.e. people, meanings, practices, and spaces. Firstly, as Liepins argues, communities are enacted and performed by people. However, despite the notion of ‘community’ often appearing as an antithesis of difference and diversity and as idealising agreement and unity (Panelli & Welch, Citation2005), the people forming any community are not a homogenous group, and power relations exist based on a range of differences. Secondly, people form a set of shared meanings through which communities are constructed and maintained (Liepins, Citation2000). These are manifested through widely held beliefs, social discourses and shared identities. In this regard, we also draw on Barrett’s (Citation2015) idea of community. Barrett’s three dimensions (i.e. interests, normativity and identity) are complementing and interrelating with Liepins’ (Citation2000) dimensions of ‘meanings’ and ‘practices’. Thirdly, practices and processes connect people to each other and enable the construction of shared meaning (Liepins, Citation2000). Through these practices, people participate in the economic, social and political life of the community. Practices can be either commonly accepted or contested. They include rituals, annual events or daily activities. The Small School Rural Community Study investigated the ways people, particularly those involved in the school (e.g. principals, teachers, pupils, parents, etc) practice or ‘do community’. Fourthly, community practices and performances are spatially constituted (Panelli & Welch, Citation2005). Thus, people practice community in particular spaces and they attach meaning to these specific spaces and sites (Liepins, Citation2000). Examples of such spaces are organisational structures and buildings like schools, churches, local shops, community halls, etc., but also natural features like rivers, forest parks or fields. In the study, we explored where ‘community’ occurs. The communities we focused on are geographical, place-based or spatial communities (i.e. associated with a particular locality or located in specific places) in contrast with imagined, ‘aesthetic’ or identity-based communities, such as social media communities, or communities of interest (Panelli & Welch, Citation2005). Hence why space is such a key dimension (Brennan & Brown, Citation2008).

The following findings are presented in four sections, each referring to one of the community dimensions, namely people, meanings, practices, and spaces.

Results and discussion

Community as a network of people: sameness and unity versus difference and diversity

Adult and child interviewees in all the case study schools perceived community as a group of people. Most children in all the schools identified their families and friends as part of their community, but also neighbours, teachers, priests, and those in other professions (i.e. shop keepers, police officers, doctors, etc.).

It’s like a lot of friendly people. (Pupil, age 8–10, Killyloch)

Everyone around you that helps and supports people. (Pupil, age 10–11, Carryhill)

Like community is just an extension of family in one sense I would say. It is not … obviously family without the blood ties so it is the same thing. […] here, if you wanted to move house you could literally ask the boy next door and he would come with a van and move house for you. So I think that is the best way to explain to people who aren’t in a community like this. It is like nearly everybody here is your cousin or your brother or your sister and because you can ask for help with the expectation of getting it. (Parent, Aghreah)

Well I suppose when I think of the word community I usually think of a scenario … […] going down the street or the village and stopping at the corner and speaking to people or … for example in November time we are doing a pantomime and that’s a […] a cross communal thing. So I suppose my idea of community is people together in … I suppose not in a common goal or common interest but in a situation together. You know if I needed something I could ring a neighbour, or I could ring a friend or I could ring [the school principal] for example or some of the teachers and it wouldn’t be a problem you know, the interest to help others is there. (Governor, St Mary’s)

As exemplified by the previous quote, communities were described as a ‘close-knit’ group of people that helped and supported each other. Rural communities are often characterised as having higher levels of social cohesion and bonding social capital than urban areas (Hemming, Citation2018). That often means that people in those areas often hold common values and are united by the same cultural elements (rituals and traditions).

Indeed, in the online survey, principals described the area where the schools were located as either mostly Protestant or mostly Catholic, with only 16% describing them as mixed or fairly mixed (Fargas-Malet & Bagley, Citation2023). In the case studies, although we found this sense of commonality, sameness and unity (in that most people in the community had the same religious background), difference and diversity were also present in participants’ depictions and understanding of community. For instance, a classroom assistant in St Mary’s talked about the diversity in the village as a feature of the whole community. Difference here was not only in terms of religious background but also sexual identity:

I do think Ballyneagh is kind of unique village. I think the fact that it is a mixed village … that there can be a hurling team in the village … that there can be an Orange Order … you know … that whatever your faith/background or cultural background … that you can find a place here and live here and have a fulfilling life here. So the idea of community for me is really important […] if I was here living on my own, I know that I could go out in the morning and have ten conversations with people walking down the street. There is community […] And I think actually for a small village, it is actually quite an accepting place. And not just along religious benefits but, you know, there are a number of gay couples living in the village and … nobody even raises an eyebrow about that […] So for me, I actually think what we have here is lovely and it is unique and the school is a big part of that too. (Classroom assistant, St Mary’s)

A pupil in the integrated school understood community as having two features – people and nature – and highlighted the fact that people ‘are different’ (see ) . We could assume that the integrated ethos of the school might have influenced this point of view, as well as her own experience of attending a school where some of her classmates were from a different religious background than her.

Figure 1. Drawing on ‘community’ by pupil, aged 10, Mullabally.

In Aghreah, some of the pupils came from Syrian refugee families, which led the school to make children and families aware of their cultural practices and try to accommodate for different cultural and religious needs. However, we did not get the opportunity to interview these families, so all we have is the information from the principal. There is no indication in our data of whether these families were considered or not as part of the community by others or the feelings of belonging they held themselves.

We would do a big celebration for Eid and the children are very aware … we have sort of a dedicated prayer space for the children that if they want to go there, they can pray at certain times. We would also explain to all the other children … […] they know what it means to have halal food … they know what it means to have your prayer … they know that Friday is their holy days where Sunday is ours. They know about the children’s prayer space, they know not to be going into it, that it is sacred for them. […] we would celebrate Eid … they know whenever the children are fasting for Ramadan and they feel very sorry for them and that Ramadan is a lot more severe than for them having to give up sweets for Lent. […] and we did like an art project were we taught all the children how to write in Arabic and we had name tags and things like that, and they know how to greet each other in Arabic. (Principal, Aghreah)

To sum up, people were perceived as a key component of the concept of community in this study, and this group of people were characterised by both sameness and difference.

Community as socially constructed: meanings

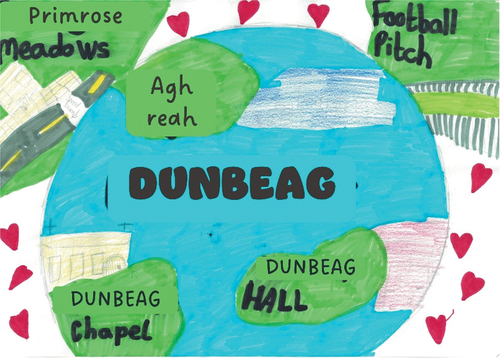

People attach meaning to their communities. As Bauman (Citation2001) argues, community is very much a ‘feel’ word. In this study, many interviewees felt a sense of belonging to their communities, even a strong sense of pride. These feelings were invoked in some of the interviews, especially with those who had forged long-term relationships and had lived in the local area for many years. Pupils also expressed these emotions in some of their drawings and accompanying explanations (see ).

To me a community means I can hold my head up and speak to anybody within my area. I am proud of where I am from … I am proud of what our community is and stands for. A community is … it is bigger than a neighbourhood, it’s stronger than a neighbourhood. It is about belonging … (Governor, Killyloch)

Figure 2. Drawing by pupil, aged 11, Aghreah.

Interviewees described their position within the community in diverse ways. Some who had been raised in a different local area and had moved into that community talked about being a ‘blow-in’. Similarly, in a study on rural parents’ sense of community and risk, Stelmach (Citation2021) talked about ‘newcomer’ families versus ‘legacy’ or ‘generational’ families. In Northern Ireland, the term ‘newcomer’ is often used to refer to members of newly arrived migrant communities. However, in this case, we are just talking about individuals (mostly from Northern Ireland) who had moved into the rural community. In contrast with Stelmach’s (Citation2021) study, we found no evidence of families who had moved into the area being treated with suspicion. In addition, as some of the following quotes suggest, being a ‘blow-in’ did not necessarily mean these interviewees did not feel part of the community. They did, and that was in part because they either brought their children to the school or they worked in the school. Stelmach (Citation2021) argued that a sense of belonging and feeling part of a community was linked to being accepted, and for that to happen, familiarity (i.e. ‘everyone knowing everyone’) was key. Our findings corroborated that, as illustrated in the quotes below:

You do become friends with the other parents as well. I know the three of us have said we’re blow-ins, L [parent in focus group]’s not but I wouldn’t have known, ok my husband’s from the village but I wouldn’t have known any of the other people here had it not been for [my daughter] going to that school. You know and I’ve made friends, very good friends from [my daughter] being at that school, for me personally so it’s not just the kids. (Parent, Aghreah)

… you’re driving down home from work there, ‘oh, there’s … xxx passed me on the road’. I knew who she was, she’s another parent, you know, we pass most evenings her taking the kids home, me coming in … that’s … I feel that’s community. And if you move into an area and with modern life, you could be leaving first thing in the morning, driving back in the evening, and not knowing who anybody was passed your driveway, you know, but the school was the opportunity for us to get to know everybody. (Parent, Killyloch)

Schools appeared to have the potential to bring the two ‘majority communities’ together, as people in the local community were crossing religious boundaries to either attend/bring their children to the school (with pupils from both backgrounds attending the integrated school or the two Controlled schools), or to work in the school, as exemplified by the case of the clerical officer in Killyloch:

I think it is nice to know the local people because I live in the area and I wouldn’t have got to know them if I didn’t work in the school. So this way I know my neighbours. And particularly, because we are from a different religious background, I wouldn’t have got to know them if I wasn’t working in Killyloch. (Clerical officer, Killyloch)

However, in another quote from the same interviewee, we can see how religious background and identity was still a powerful marker which prevented people to have closer and more meaningful relationships with those from a different religious background:

Researcher: And would you have good relationships with the parents and the families?

Clerical Officer: Yeah, but I don’t really hang out with them because we are in different religious communities. So I don’t really go to their functions and they don’t really come to ours. I wouldn’t see them other than a school function. A lot of the families here kind of hang out together because they are in the same network. But I would see them at school functions and things like that. […] Or you would see them in the shops in [nearby village] or you know, you would see them out and about and they would stop and have a chat. But we wouldn’t be friendly as such … go to each other houses for coffee or anything.

To sum up, participants in the study showed how they attached meaning to their communities and how most held feelings of belonging and pride in their own communities.

Community as constantly performed: practices – ‘doing community’

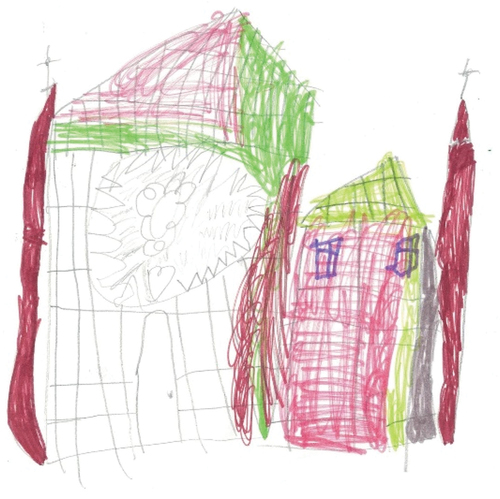

Community was performed every day, and this happened in and outside school. Many of the community practices performed in and around the schools were of a religious nature, as most primary (urban and rural) schools in Northern Ireland do have a religious character. Both the quantitative and qualitative data emanating from our study showed that. For instance, in our survey, 78% of principals indicated that church/religious leaders were coming to the school regularly to visit pupils and teachers. The relationship between the church and the school appeared less strong in integrated schools, and it was particularly strong for Catholic Maintained schools, as regular meetings between staff and religious/church leaders were found to be more common in Catholic Maintained schools than Controlled ones (51% versus 22%). In addition, in the case studies, a larger proportion of pupils drew the church in the two Catholic Maintained schools compared to those in the other schools, when asked to draw about their communities (e.g. see ).

Figure 3. Drawing by pupil, aged 7, St Mary’s.

As Mitchell (Citation2006) argues, religion can bring people together as they participate in the same activities and rituals, thus creating feelings of belonging. In the case studies, some of these activities and rituals included Christmas concerts or plays, preparation for the Catholic church sacraments, etc.

Because we are a Catholic primary school then there would the onus on us as a school to prepare the children for the Sacraments. So there’s three Sacraments which are received at primary school level; the First Penance, First Holy Communion and the Sacrament of Confirmation. So it’s up to the teachers and school to instruct and prepare the boys and girls for those Sacraments. That’s done in conjunction with the Parish Priest. So there’s quite a bit of engagement there with the Parish Priest coming in to visit the school and the teachers and the Parish Priest coming together sort of planning and discussing and organising ceremonies and so on. (Principal, St Mary’s)

Although religious practices could be considered divisive, as each religious community perform different ones, we found that they also had the potential to bring communities together if the children were taught in the same school. The Catholic sacraments are very important to Catholic rural communities and were big events in the school calendar of the Catholic Maintained schools, but pupils with a Catholic background in the Integrated school and in the two Controlled schools were also prepared for these. In these schools, children with a Protestant background (or other) also wanted to support their friends in their religious rituals and often attended the ceremonies:

But what you will find is a lot of our Protestant or other children want to attend the Communion or the Confirmation to see their friends. They do their learning separately, but they still want to be part of it on the day. So parents will come to me and ask if it’s ok if their child could go along and see the ceremony. We say absolutely no problem and they come along and they’re there you know. So it’s completely cross community even right up to the parents who want to go along. (Teacher, Carryhill)

Not all ‘community practices’ were of a religious nature. Everyday practices like parents meeting at the school gates, people greeting each other in the shops or helping neighbours or other parents with whatever they needed were described by participants in all the schools.

And the parents are a good group for each other because at the end of the day nobody ever knows what’s going on with other people and because it is such a small school everybody mucks in. Something could be happening in someone else’s house, and you think the simplest thing like running their kids to school or bringing their kids home or taking them away for an afternoon or something so simple can mean so much to another parent because it is such a small community. […] it is because it’s a small school and we all do kind of, everybody meets at the gate. (Parent, St Mary’s)

There were also school community events that were celebrated by all the communities. These were sports days or harvest assemblies, among other examples. However, some community events were particular of the cultural background of either Catholic or Protestant communities. Although some schools tried to include everybody, some differences were hard to reconcile.

To something like breakfast with Santa, yeah, there were lots of them. The jubilee event there were some … maybe because it was jubilee and the royal family that might have had a slight bearing on that, but there definitely were people from the Catholic community. Usually for our Christmas concert the principal from [local Catholic Maintained school] would come down and bring some pupils, they would sit and watch it in the church. And we do the same. (Teacher, Killyloch)

Schools participating in Shared Education Programmes appeared more likely to bring communities from the two main religious background together through different activities and events, such as Christmas concerts, as exemplified in the above quote. Another example would be pupils from Killyloch and pupils from their neighbouring Catholic Maintained school going litter-picking to a local village together once a month. They also shared resources, whereby one of the schools provided early morning care (breakfast clubs) and the other provided after-school activities for the pupils of both schools. In the survey of principals, we found that 75% of schools had recently participated in shared education programmes, and only 20% had never done so. We also found that schools that had less than 80 pupils were more likely to have participated in Shared Education programmes. The principal of St Mary highlighted the importance of their Shared Education programme with the village Controlled school in terms of bridging communities:

… there’s a crocheting and knitting group in the community and they made a huge model of the whole village of Ballyneagh, they knitted it and crocheted it. […] So, it was on the news about the Ballyneagh crochet village, erm … and that took place in the Orange Hall. So, again, we got the opportunity to go. […] ourselves and [Ballyneagh’s Controlled School] got together, and […] we visited the Orange Hall together. And the ladies in the crocheting club let us see what they were doing, they had some refreshments and all for us, and also told us a little bit about the Orange Hall […] So I personally had never been in an Orange Hall before and that was an experience and that was something, you know, again, a one-off and unique to our community and I can’t imagine that there are many Catholic primary schools visiting the local Orange Hall. (Principal, St Mary’s)

However, one of the parents from St Mary’s felt that the Shared Education partnership between the schools in the village could be further utilised and emphasised more than it was at present, while two other parents went further and were keen for the two schools to amalgamate into an integrated school:

I can see the rationale for keeping the schools separate cos there’s different things that the schools are going to do. But I do think there should maybe be more integration between the two in terms of, like even, the boys were lucky this year they had enough boys within the class to have a school football team and I just even think that the two schools could come together for something like that […] even maybe shared classes that they could do to build you know relationships with people on the other side of the community if you like you know and bring people closer together so you’re extending your pool of friends and getting to know people right through the village which can only benefit the village. (Parent, St Mary’s)

To summarise, community practices were often described by participants in the case studies, and these occurred in and outside school. Some of these practices were able to bridge communities, with integrated and shared education having an important part to play in that, and other practices reinforced divisions.

Community as place-based: spaces

The perception of community that the research participants had was very much place-based. Place is much more than just space. Gieryn (Citation2000) conceptualised place as mediating social life, and having three main features: geographic location, material form, and meaning and value. In terms of the geographic location, the communities featured in our case studies were located in a range of rural areas, including villages and townlands. For instance, while St Mary’s school was located within a small village, Killyloch was situated in a rural area surrounded by farmland, where the nearest shop was miles away. That had implications for the community as well as for the role and position of the school within said community.

I suppose community is really the people of the local area … emmm … and this is such a rural area, there is no village as such … we have the church and the schools … so in some ways they form the community here. (Teacher, Killyloch)

Regarding the ‘meaning and value’ feature, we found many examples in our case studies of how interviewees gave meaning and value to place, as well as illustrations of their ‘attachment to place’. The community that the schools served was characterised as ‘tight’, ‘close-knit’, ‘strong’, ‘lovely’ and even as ‘real’. Locality was key in these, as well as its rurality. Interviewees often referred to the community’s rural character, which they attributed meanings to and was often compared to urban communities.

In terms of the ‘material form’ dimension, various spaces served multiple functions for the community (Hemming, Citation2018). The key spaces in these rural communities were the church and the school. Indeed, when asked about the key organisations of the community their school served, most of the 87 surveyed principals that answered this question identified the church (90%) and the school (80%) (Fargas-Malet & Bagley, Citation2023). Sporting associations were also identified as one of the most influential by nearly half of the surveyed principals (n = 43), with most of these being principals of Catholic Maintained schools (39 out of 43). This is because Gaelic Athletic clubs (GAC) are very influential and popular in Catholic rural areas in Northern Ireland (Fargas-Malet & Bagley, Citation2023).

Both the churches and the schools served as meeting points for the community. Community events, activities and rituals were often hosted in their premises. In some cases, schools did use church premises for the events they organised. On the other hand, school premises were used by the community in a myriad of ways too: from being used by community groups to holding all types of community events.

So our premises are used by the local yoga club in the wee village beside come out and use our assembly hall. Other groups would come and use the grounds for whatever they would like to use if for. We hold a clothes bank on the property that the local community comes and donates to. We’re a polling centre for everybody in this local community. (Principal, Carryhill)

Discussion and conclusion

The paper applied a mixed method approach to investigate in-depth small rural school-community relations and to make greater sense of the meaning of community in the divided and segregated post-conflict society of Northern Ireland. Methodologically, in many studies in this field, the voice of the pupil has been missing (Fargas-Malet & Bagley, Citation2022). Hence, in the qualitative part of our investigation, we sought, as far as we could, to capture pupil perspectives via a draw-and-tell technique (Punch, Citation2002) and class discussions. The engagement of the pupils revealed their sense of pride and belonging to their own local communities and their schools, and the ways in which these findings could be accommodated in relation to the notion of community we adopted.

In presenting the findings, the paper primarily followed Liepins’ (Citation2000) four key dimensions of community (i.e. people, meanings, practices and spaces) as a framework by which to analyse and conceptualise the ways in which community is understood and described by individuals connected to five small rural schools. In below, we have sought to figuratively draw on those four dimensions to frame and incorporate key data, concepts and studies referenced in our findings. Indeed, the data reported here suggested that all four facets were present within participants’ perceptions of community. We have also shown how the four dimensions operated simultaneously in different ways and to different degrees.

In terms of the ‘people’ dimension, we have seen how participants in the study understood community as being a ‘close-knit’ group of people, characterised by high levels of social cohesion and bonding social capital. Although sameness and unity were often reinforced in individuals’ narratives, some also emphasised the diversity within the communities they lived in. Regarding meanings, despite drawing distinctions between ‘blow-ins’ and those who grew up in the community, participants displayed a sense of belonging and pride of being part of their communities regardless. In terms of practices, multiple examples of ‘doing community’ were given by all participants. Finally, the concept of ‘community’ in this study was very much ‘place-based’, and spaces were key to this idea of community (which was being performed in a range of them), with the school occupying a key position.

As Cuervo (Citation2014) argues, ‘small schools are often the hub of many rural communities’ (p. 643). In our study, schools were described as the ‘meeting point’ of the community; ‘the vocal point’, ‘the focal point’ and ‘the linchpin’. Although not everybody described them as being at the heart of the community, all participants in our study recognised that they played a crucial part. However, Cuervo also argues that ‘the relationship between small schools and communities is often presented as a powerful one; however, too often as a harmonious, natural and simple construction’ (Cuervo, Citation2014, p. 644). Our data suggest that most participants did see this relationship as powerful but also harmonious and natural. A viewpoint encapsulated in the following quote from a parent in the townland of Killyloch:

I think if the school wasn’t there, that would be … nearly an end to what you can describe as the community. It would just be an area you live in. […]. So, that’s it, done, last generation of a community, you know, dead basically. (Parent, Killyloch)

There were only a few minor instances where there was some indication of schools, in some way, eroding social cohesion. Indeed, previous research has concluded that rural faith schools can erode but also promote social cohesion and contribute to positive community relations (Hemming, Citation2018). The only notable dissenting voice came from a youth community leader who grew up in the townland where Aghreah school was located:

[…] up until relatively recently it always was kind of a sticking point for a lot of people … you either went to the school, or you didn’t go to the school and there was a bit of an internal divide … some people I know have went to the school for maybe three or four years and then left because they had issues … […] the school has grown so much with people from … a lot of people are bussed in … […] I would have parents talking to me … and sometimes they are very happy and sometimes […] they can feel like the local kids aren’t the priority for them. (Community Leader, Aghreah)

However, we recognise that the key informants in our case studies were those with direct contact with the school, who are much more likely to have a positive, or even an idealised, view of the school. Thus, a limitation of the study is that we did not seek the perspective of community members without a direct contact of the school, which might be very different from those that do.

As mentioned earlier, Barrett (Citation2015) recognises that communities are contested spaces, in which ‘contradictory dynamics push and pull at each other’ (p. 194). In a previous article (Fargas-Malet & Bagley, Citation2023), we posed the question whether ‘the close relationship between small rural primary schools and the divided communities they serve, while pulling together, are simultaneously (though not necessarily deliberately) still pushing apart’. Judging by the qualitative data in our case studies, it is hard to see many instances of ‘pushing apart’. Again, that might be because of the nature of the participants in the study. Despite that, what our case studies demonstrate is that the relationship between communities within the schooling system in rural areas is much more complicated than it often appears, not least when situated within a divided society. For instance, one case study school was a Controlled (state) school which had more pupils and teachers from a Catholic background than it did from a Protestant one. The other Controlled school, the smallest in our sample, had an extremely close relationship with the local Catholic school, and had applied for a shared campus, with the professional and cultural desire of integrating those communities further. Indeed, our findings suggest how integrated education (in the case of our integrated school) and shared education programmes (adopted by four of our five case study schools), have the potential to bridge Catholic and Protestant communities in rural areas, and thus play a significant part in the process of peace and reconciliation. Study findings have demonstrated how community relations have indeed changed since Rosemary Harris’ anthropological study of Ballybeg in the rural border areas of NI in the 1950s/60s (Harris, Citation1972). Thus, the continual threat of closure faced by these small rural schools and the implications for the divided communities they serve arguably have important ramifications beyond the purely educational. The implications of their removal result in the loss of a key institutional social and cultural driver by which these divided communities may be brought closer together.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Montserrat Fargas Malet

Montserrat Fargas Malet is a Research Fellow at the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University Belfast, and has been conducting research there since 2005. Her background is in Sociology (BSsc), Women’s Studies (MA), and Education (PhD).

Carl Bagley

Carl Bagley is Professor of Educational Sociology at the Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University Belfast, and previous Head of School (2017–2023). Prior to joining Queen’s he was Head of the School of Education at Durham University (2013–2017).

Notes

1. This was a limitation of the study as we did not have full control over the selection of participants within the school (i.e. parents, staff and pupils).

References

- Autti, O., & Hyry-Beihammer, E. K. (2014). School closures in rural Finnish communities. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 29(1), 1–17.

- Bagley, C., & Hillyard, S. (2014). Rural schools, social capital and the big society: A theoretical and empirical exposition. British Educational Research Journal, 40(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3026

- Barrett, G. (2015). Deconstructing community. Sociologia Ruralis, 55(2), 182–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12057

- Bauman, Z. (2001). Community: Seeking safety in an insecure world. Polity.

- Borooah, V. K., & Knox, C. (2013). The contribution of ‘shared education’ to Catholic–Protestant reconciliation in Northern Ireland: A third way? British Educational Research Journal, 39(5), 925–946. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3017

- Brennan, M. A., & Brown, R. B. (2008). Community theory: Current perspectives and future directions. Community Development, 39(1), 1–4.

- Cedering, M., & Wihlborg, E. (2020). Village schools as a hub in the community-a time-geographical analysis of the closing of two rural schools in southern Sweden. Journal of Rural Studies, 80, 606–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.09.007

- Corbett, M., & Tinkham, J. (2014). Small schools in a big world: Thinking about a wicked problem. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 60(4), 691–707.

- Cuervo, H. (2014). Problematizing the relationship between rural small schools and communities: Implications for youth lives. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 60(4), 643–655.

- DE. (2022). School enrolment - school level data 2021/2022. Department of Education. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/publications/school-enrolment-school-level-data-202122

- Dillman, D., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th ed.). Wiley & Sons.

- Driessnack, M. (2006). Draw-and-tell conversations with children about fear. Qualitative Health Research, 16(10), 1414–1435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306294127

- Edmonds, W. A., & Kennedy, T. D. (2017). An applied guide to research designs: Quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071802779

- Fargas-Malet, M., & Bagley, C. (2022). Is small beautiful? A scoping review of 21st-century research on small rural schools in Europe. European Educational Research Journal, 21(5), 822–844. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041211022202

- Fargas-Malet, M., & Bagley, C. (2023). Serving divided communities: Consociationalism and the experiences of principals of small rural primary schools in Northern Ireland. British Journal of Educational Studies, 71(3), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2022.2110857

- Gieryn, T. F. (2000). A space for place in sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 463–496. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.463

- Halsey, R. J. (2011). Small schools, big future. Australian Journal of Education, 55(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494411105500102

- Hamilton, J., Hansson, U., Bell, J., & Toucas, S. (2008). Segregated lives. Social division, sectarianism and everyday life in Northern Ireland. Institute for Conflict Research.

- Harris, R. (1972). Prejudice and tolerance in Ulster: A study of neighbours and ‘strangers’ in a border community. Manchester University Press.

- Hemming, P. J. (2018). Faith schools, community engagement and social cohesion: A rural perspective. Sociologia Ruralis, 58(4), 805–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12210

- Hughes, J., Lolliot, S., Hewstone, M., Schmid, K., & Carlisle, K. (2012). Sharing classes between separate schools: A mechanism for improving inter-group relations in Northern Ireland? Policy Futures in Education, 10(5), 528–539. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2012.10.5.528

- Kearns, R. A., Lewis, N., McCreanor, T., & Witten, K. (2010). Chapter 11 school closures as breaches in the fabric of rural welfare: Community perspectives from New Zealand. In P. Milbourne (Ed.), Welfare reform in rural places: Comparative perspectives (pp. 219–236). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Leonard, M. (2009). ‘It’s better to stick to your own kind’: Teenagers’ views on cross-community marriages in Northern Ireland. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830802489242

- Liepins, R. (2000). Exploring rurality through ‘community’: Discourses, practices and spaces shaping Australian and New Zealand rural ‘communities’. Journal of Rural Studies, 16(3), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(99)00067-4

- Loader, R. (2022). Shared spaces, separate places: Desegregation and boundary change in Northern Ireland’s schools. Research Papers in Education, 37(6), 1097–1118. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2021.1931947

- Loader, R., & Hughes, J. (2017a). Balancing cultural diversity and social cohesion in education: The potential of shared education in divided contexts. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2016.1254156

- Loader, R., & Hughes, J. (2017b). Joining together or pushing apart? Building relationships and exploring difference through shared education in Northern Ireland. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2015.1125448

- McCully, A., & Clarke, L. (2016). A place for fundamental (British) values in teacher education in Northern Ireland? Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(3), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2016.1184465

- Mitchell, C. (2006). Religion, identity and politics in Northern Ireland. Boundaries of belonging and belief. Routledge.

- Moreno-Pinillos, C. (2022). School in and linked to rural territory: Teaching practices in connection with the context from an ethnographic study. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 32(2), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.47381/aijre.v32i2.328

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. (2011). Census.

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. (2015). Review of the statistical classification and delineation of settlements.

- Panelli, R., & Welch, R. (2005). Why community? Reading difference and singularity with community. Environment and Planning A, 37(9), 1589–1611. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37257

- Punch, S. (2002). Research with children: The same or different from research with adults? Childhood, 9(3), 321–341.

- Schatzman, L., & Strauss, A. L. (1973). Field research: Strategies for a natural sociology. Prentice Hall.

- Shortall, S., & Shucksmith, M. (2001). Rural development in practice: Issues arising in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Community Development Journal, 36(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/36.2.122

- Sörlin, I. (2005). Small rural schools: A Swedish perspective. In A. Sigsworth & K. J. Solstad (Eds.), Small rural schools: A small inquiry (pp. 18–23). Interskola .

- Stelmach, B. (2021). Using risk to conceptualize rural secondary school parents’ sense of community. School Community Journal, 31(1), 9–40.

- Villa, M., & Knutas, A. (2020). Rural communities and schools–valuing and reproducing local culture. Journal of Rural Studies, 80, 626–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.09.004

- Walford, G. (2001). Doing qualitative educational research: A personal guide to the research process. Continuum.