ABSTRACT

For a long time, internationalisation strategies of higher education institutions across the world focused on international student mobility. However, international student mobility is a socially selective process, whereby students from lower socio-economic backgrounds are less likely to participate. Consequently, in recent years ‘internationalisation for all’, ‘inclusive internationalisation’ and ‘internationalisation at home’ have become prominent terms in internationalisation strategies, aiming to provide internationalisation activities to all students, including those who remain at home. To our surprise, however, existing scholarship today did not investigate whether offering a broader array of internationalisation activities also reaches the objectives of such new internationalisation strategies, namely to reach a broader group of students, including those from traditionally disadvantaged backgrounds. To this end, in this paper, we investigate the likelihood of different (social) groups to participate in different internationalisation activities, both at home and abroad, through an online survey conducted in 2019 at three institutions in Belgium and the Netherlands (n = 2567). Our findings clearly indicate that the social composition of student populations needs to be taken into account when designing internationalisation strategies. Our results indicate that simply broadening the type of activities is not sufficient, as students from lower socio-economic backgrounds showed to be less likely to participate in any internationalisation activity. Overall, the findings suggest that inclusive internationalisation might best be reached through integrating internationalisation into the formal curriculum, in order to circumvent the barriers that might exist to participate in activities outside of the formal study schedule.

Introduction

In a context of massive growth in the number of students that attend higher education, higher education institutions (HEIs) across the world made significant efforts to internationalise higher education. However, the massification and internationalisation of higher education present significant challenges to international education in terms of equity (see e.g. Schendel and McCowan Citation2016; De Wit and Jones Citation2018). After all, the internationalisation of higher education has been connected to international student mobility for a long time, which is a socially selective process (see e.g. Netz et al. Citation2021, for a recent overview). Although admittedly there have been efforts to lower the barriers to disadvantaged groups, inequalities in participation in international student mobility are persistent over time (see e.g. Netz and Finger Citation2016). As a result, current conceptualizations of ‘internationalisation’ acknowledge two components, namely internationalisation ‘at home’ and ‘abroad’ (Knight Citation2012), and it has been argued that institutional strategies that move beyond mobility should now be the starting point of internationalisation strategies (De Wit and Jones Citation2018). Such strategies aim to foster ‘internationalisation for all’ or ‘inclusive internationalisation’, which includes international activities at the home institution. Despite the interest in the scholarly community for ‘internationalisation at home’, ‘internationalisation for all’ and ‘inclusive internationalisation’ strategies and activities, we noticed that – to our knowledge – no studies exist that investigate whether different internationalisation activities also reach different student groups. This surprising observation constitutes a significant gap in the academic literature. Therefore, we empirically explore whether students from different social groups are likely to participate in different internationalisation activities, both at home and abroad, at three HEIs in Belgium and the Netherlands. Our results are based on an online survey conducted in 2019, which resulted in a sample of 2567 respondents.

The contribution of our paper to the academic literature is twofold. First, our paper connects the academic literature on international higher education and the sociological literature on the social stratification of students’ experiences within higher education. Such approach allows to critically assess whether inclusive internationalisation efforts really provide internationalisation to all students. Our focus on social selectivity in participation in internationalisation activities also contributes to the sociological literature on social inequalities in higher education, which predominantly focused on assessing inequalities in access to higher education (e.g. Reay, David, and Ball Citation2005; Reay et al. Citation2001) and/or social inequalities in educational attainment and labour market outcomes (e.g. Christie et al. Citation2018), rather than what happens within higher education (Reay Citation2021) – i.e. students’ lived experiences. In our analyses, we particularly focus on social class and migration background. Second, it has been observed that there is a lack of practical applications of scientific findings in the international higher education literature (Almeida et al. Citation2019; Ogden, Streitwieser, and Van Mol Citation2021). Thus, our explicit focus on empirically assessing whether inclusive internationalisation activities are indeed reaching diverse audiences allows formulating tangible recommendations for daily practice.

In sum, whereas internationalisation of higher education and inclusive internationalisation strategies figure high on the agenda of HEIs, our knowledge on social selectivity in participation in internationalisation activities remains limited. In this paper, we provide exploratory quantitative empirical insights into these dynamics.

Background

Adding a sociological perspective to the inclusive internationalisation literature

Over the past decade, Sociologists have started to focus on the experiential dimension of higher education, showing how HE is not a neutral environment. Social markers such as class, gender and ethnicity significantly shape and structure students’ abilities and experiences in higher education (Stuber Citation2011; Netz and Sarcletti Citation2021). Sociological studies particularly indicate that students from different socio-economic and/or migration backgrounds arrive with different levels of economic, social and cultural capital at higher education, which has an important impact on their higher education experiences (Stevens, Armstrong, and Arum Citation2008; Armstrong and Hamilton Citation2013; Hurst Citation2018). Several studies highlighted, for example, how students with a different socio-economic background engage in different activities throughout higher education (Armstrong and Hamilton Citation2013; Walpole Citation2003; Wilbur and Roscigno Citation2016; Pascarella et al. Citation2004). Some activities offered outside of the formal curriculum might be too expensive for working class students as they often face more financial constraints. In fact, they often have to work during their studies, which additionally limits the time they can spent on such activities (Hurst Citation2018; Armstrong and Hamilton Citation2013). Furthermore, differences in cultural and social capital might also make students unaware of the existence of certain activities. For instance, students from lower socio-economic backgrounds have been shown to be ‘less likely to explore unfamiliar social and cultural worlds’ (Stuber Citation2011) because of their socialisation process. As their ‘ability to take advantage of the many opportunities offered in higher education is significantly restrained by their working class status’, the ‘hidden injuries of class’ come forward here (Sennett and Cobb Citation1973, cited in Stuber Citation2006, 304). In contrast, students from higher classes are much more comfortable in exploring the new setting of higher education, as they are socialised in comparable social and cultural environments. Broadly speaking, sociological research thus points out that there are classed pathways through higher education.

The empirical sociological literature on the role of ethnicity in higher education experiences presents more mixed evidence. Whereas some studies report students with a migration background to be disadvantaged in higher education compared to the majority population, other studies argue the opposite, i.e. that students with a migration background can also outperform the majority population with similar socio-economic background (see e.g. Khattab Citation2018, for reviews of such conflicting evidence; Feliciano and Lanuza Citation2017). The latter is often referred to as the ‘immigrant paradox’. A study of Li (Citation2018) in the UK aimed to explain this paradox, and indicated that students from ethnic minority backgrounds (defined through standard UK census coding, namely black Caribbean, black African, Indian, Pakistani/Bangladeshi, Chinese, and ‘Other’) might actually be extra motivated to succeed in higher education, in order to combat the possible negative effects of discriminatory practices in the labour market and wider society. After all, it has been amply demonstrated that discrimination based on ethnic origin exists in labour markets (see e.g. Blommaert, Coenders, and van Tubergen Citation2014; Ahmad Citation2020; Zschirnt Citation2020; Zschirnt and Ruedin Citation2016), and higher education students with a migration background are aware of this. As such, Li argues, these students might have a ‘reinvigorated ambition’ to succeed against the odds. From this perspective, it can be expected that students with a migration background are more likely to invest in internationalisation activities. However, it should be added that the intersection between socio-economic background and ethnicity should not be overlooked. From this perspective, we can expect particularly ethnic minority students from higher SES families to participate in such activities.

In this paper, we aim to connect the literature on social inequalities in students’ lived higher education experiences to the academic literature on ‘inclusive internationalisation’. This literature emerged recently as a response to the predominant focus of the general internationalisation literature on international mobility and associated social selectivity. According to this perspective, an inclusive approach must address the issue that current internationalisation policies and practices can often magnify or reproduce social inequalities (Janebova and Johnstone Citation2021; De Wit and Jones Citation2018). Thus, to increase inclusivity in internationalisation of higher education, a starting point is to draft internationalisation strategies that include the specific composition of the student population at respective institutions and to tackle internationalisation from a broader angle that goes beyond mobility. Therefore, institutional actions in direction to the promotion and implementation of processes such as internationalisation at home (Almeida et al. Citation2019; Beelen and Jones Citation2018), internationalisation for all (Beelen and Jones Citation2018), and internationalisation of the curriculum (Leask Citation2015) could be a good point to start to talk about inclusivity and equity. Consequently, in this paper, we make a distinction between internationalisation activities abroad, which mainly involve the physical mobility of students across international borders, and internationalisation activities at home. As indicated above, we noticed that – to our knowledge – today no studies investigated empirically how different activities within these two broad strands might find its way to different student populations. This, however, is a very relevant question if we consider the sociological literature described in the first paragraphs of this section.

Social selectivity in study abroad participation

Over the past decade, social inequalities in study abroad participation have been documented extensively (for a recent overview of existing studies, see Netz et al. Citation2021). Notwithstanding variation between countries, students who participate in international exchanges are primarily female, from an ethnic majority background and higher socio-economic background (Netz et al. Citation2021). Social selectivity regarding the socio-economic background of students has been shown to relate to differences in economic, cultural and social capital. For example, students or their parents often cannot afford the financial costs study abroad brings along (Netz and Finger Citation2016), and they also do not always have access to social networks wherein study abroad is valued, or where they can receive valuable information and assistance (Netz et al. Citation2021). This aligns with the sociological insights on inequalities in higher education explained in the previous section.

Regarding ethnicity, the existing literature is less conclusive, albeit it indicates in most countries ethnic majority students participate most in study abroad (Netz et al. Citation2021). Students with an ethnic minority background might face similar problems as students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, that is, to dispose over different social, economic and cultural capital compared to the majority population. On the other hand, as indicated by Netz and Sarcletti (Citation2021), students with a migration background already dispose of some resources that can give them an advantage in terms of making decisions to study abroad: they tend to have better intercultural and language skills, and are already used to being exposed to different cultures. Indeed, it has been reported that second generation migrants in Germany are more likely to move abroad compared to the majority population (Middendorff et al. Citation2013, cited in Netz et al. Citation2021). Or, in other words, they already dispose of what has been coined ‘migration-specific capital’ (Massey and Espinosa Citation1997) or ‘mobility capital’ (Murphy-Lejeune Citation2002), which lowers the costs of subsequent international moves, making it easier to decide to move.

Internationalisation at home as an alternative for social selectivity in international mobility?

Beelen and Jones (Citation2015) defined internationalisation at home as the purposeful integration of international and intercultural dimensions into the formal and informal curriculum, thus including all students at institutions within domestic learning environments. Leask (Citation2009) defined internationalisation of the curriculum as the incorporation of an international and intercultural dimension into the preparation, delivery and outcomes of a programme of study, so that it purposefully develops all students’ international and intercultural perspectives as global professionals and citizens. These approaches are very inclusive as both definitions englobe all students studying at the institution and reflect on the need to develop an institution-wide approach to internationalisation (De Wit et al. Citation2015) that include all actors as well as represents the specific composition of the student population when designing internationalisation activities. This indicates the importance of acknowledging that not all students are the same and that not all students have the same needs (Perez-Encinas, Rodriguez-Pomeda, and de Wit Citation2020). Much of the literature on internationalisation at home, however, focused on the outcomes of such activities (see e.g. Glass Citation2012; Soria and Troisi Citation2014; Jon Citation2013; Watkins and Smith Citation2018), rather than the profile of those who participate in such activities, which is the approach we adopt here. Focusing on participation, however, allows assessing whether internationalisation activities reach relevant target groups in the first place.

In sum, we believe that a comprehensive and an inclusive system through internationalisation at home, including internationalisation activities for all, should be a priority in the internationalisation agenda of HEIs: to engage with all stakeholders and mainly students, to offer different ways to live ‘an international experience’, to recognise the value of diversity of different social groups and to finally bring equity and inclusivity in higher education through a range of different activities. However, in order to do so, solid scientific knowledge is needed on which internationalisation activities are likely to reach different or wide student populations – focusing both on international activities at home and abroad.

Data, measures and methods

Sample

Our analyses are based on an online survey, conducted in the period April – September 2019 at three universities in Belgium and the Netherlands. The survey focused on the internationalisation of higher education, and contains detailed information on the activities – both at home and abroad – students are willing to participate in or already participated in. The online survey relied on total population sampling, whereby all students at the three HEIs received an invitation to participate. We filtered out double cases, as well as alumni, PhD students, current exchange students, and students who did not identify with male or female gender due to the small number of cases in this category which does not allow for any meaningful statistical analyses for this group (n = 14). The choice to exclude PhD students was based on the fact that these students often have a different trajectory and also likely dispose of different financial means compared to bachelor and master students in the two countries. The choice to exclude current exchange students was made as they would bias the results, as they could interpret the internationalisation activities at home differently in the survey. That is, they could refer to their home institution in the country of origin. In addition, respondents that had incomplete answers on all dependent variables were filtered out as well. As a result, our analyses include 2567 respondents.

Measures

Dependent variables

The dependent variable is the likelihood to participate in a given internationalisation activity, based on the question ‘How likely is it that you would participate in the following internationalisation activities during your degree (if available)?’. Respondents had to rate such likelihood for 24 possible internationalisation activities on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ‘Extremely unlikely’ to 5 ‘Extremely likely’. Respondents who replied they already participated in the activity were assigned also a score of 5 on the variable. The list of 24 activities was based on the activities that were already offered by the three institutions, the activities the international offices indicated they would like to develop or were thinking to develop, as well as internationalisation activities that have been reported in the academic literature. This list was offered in a randomised form, in order to reduce response order bias.

Independent variables

In this paper, we particularly focus on different student populations in terms of social class and migration background. The choice for these two groups has been made in the Belgian and Dutch context, where students from lower socio-economic background and/or with an ethnic minority background are defined as groups that need special attention in terms of inclusion in higher education (see e.g. VLOR Citation2015).

We use two measures of social class. First, we use parental education as a proxy for socio-economic status (SES). Following large household surveys, we classified highest level of completed education into three categories, following the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), namely low (1, ISCED levels 1 & 2), medium (2, ISCED levels 3 & 4), and high (3, ISCED levels 5 and 6), and use the highest reported category by one of the parents. We made this choice, as there is a plurality of family types, meaning that a significant share of our respondents did not provide information on both parents – which can be due to e.g. divorce, loss of contact or death of one of the parents. As only 55 respondents could be classified as low socio-economic background – which is logical in a context characterised by increasing levels of educational attainment and social selectivity in access to higher education – we recoded this variable into a binary variable (0 = no higher education; 1 = at least one parent obtained a higher education degree). Second, we also included students’ subjective social status’(SSS), as it has been indicated that students material class does not necessarily correspond with students subjective social status, but individuals’ subjective social status is important in the choices individuals make as well as in terms of their behaviour (D'Hooge Citation2019). We measured SSS with the question ‘do you see yourself belonging to … ?’ (1 = The working class of society, 2 = the lower middle class of society, 3 = the middle class of society, 4 = the upper middle class of society, 5 = the higher class of society, 6 = I don’t know).

Our measure of migration background is based on the definition put forward by the VLOR, who define migration background with respondents’ nationality as well as the nationality of their parents. If either the respondents or any of both parents do not have the Belgian or Dutch nationality, they are classified as having a migration background. The result is a categorical variable (0 = majority population student, 1 = migration background (no Belgian or Dutch nationality, or one of the parents without Belgian or Dutch nationality at birth, and followed at least 2 years of secondary education in Belgium or the Netherlands), and 2 = international degree mobile students).

Control variables

We control for several variables that likely influence students’ likelihood of participation in internationalisation activities. First, gender is included as a dichotomous variable (0 = female, 1 = male). Second, age is included as a continuous variable. Third, we control whether respondents have children, as this might put constraints on their time and availability to participate in certain internationalisation activities (0 = no, 1 = yes). Fourth, study level is measured as a binary variable with two levels (0 = Bachelor, 1 = Master). Fifth, we control for study field, as participation in study abroad has been shown to significantly vary across study fields, which might hence also be the case for internationalisation activities at home. This variable is based on the faculty where a student studied. We recoded the faculties of the participating universities to Eurostat’s Field of Science and Technology Classification, which consists of six categories (1 = Social Sciences, 2 = Engineering and Technology, 3 = Medical and Health Sciences, 4 = Agricultural Sciences, 5 = Natural Sciences, 6 = Humanities). The category of Social Sciences is used as a reference category, as it is the largest group. Finally, we control for the university respondents were enrolled at, as the three participating universities have different levels of internationalisation and different student population. (0 = institution A, 1 = institution B, 2 = institution C).

An overview of descriptive statistics of the dependent and control variables can be consulted in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Analytical strategy

We first analysed the data descriptively, in order to get an overview of which activities the general students population is more likely to participate in. Thereafter, and given the ordinal nature of the dependent variable – the likelihood to participate in a given internationalisation activity – we estimated ordered logit models to investigate whether any differences can be observed across different (social) groups within the general student population.

Results

Descriptive analysis

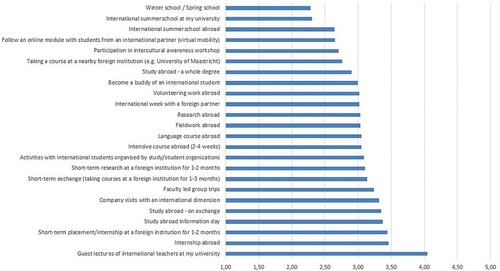

In , we can observe a huge disparity with regards to the likelihood of participation in specific internationalisation activities. Winter, Spring and Summer schools at home seem to be among the least popular activities, as students rated their likelihood of participation significantly lower compared to other activities. In contrast, guest lectures from international lecturers clearly stand out as one of the activities that students are most likely to engage in. This finding might be related to the fact that for higher education students in the two countries, it is quite common to receive guest lectures from international speakers. Stays abroad – both short and long-term internships or study abroad activities – figure also high.

Figure 1. Descriptive analysis of the likelihood of participation in internationalisation activities (1 = extremely unlikely, 5 = extremely likely / already participated, mean scores).

This general figure, however, might mask disparities between different groups of students. Therefore, in the next section, we more closely investigate whether different social groups have different preferences, controlling for confounding factors.

Multivariate analysis

presents ordered logit models on the likelihood of participation in all internationalisation activities described above. The table only presents the results of the independent variables, controlling for possible confounding factors. Full models are available in online annex 1.

Table 2. Ordered logit models on the likelihood of participation in different internationalisation activities, odds ratios.

All models in indicate that students from families where not one of the parent(s) obtained a higher education degree are less likely to participate in all internationalisation activities, both at home and abroad. This relationship is statistically significant for all internationalisation activities except for participation in an international Summer schools at home, virtual mobility, becoming a buddy of an international student, company visits with an international dimension, short-term exchanges and placements, taking a course at a nearby foreign institution, study a full degree abroad, and faculty-led group trips. Overall, these results indicate that students from lower socio-economic backgrounds are less likely to participate in internationalisation activities, but they also indicate that there might be potential for more inclusion in internationalisation activities that are organised at home or that are rather short-term. This also becomes apparent when investigating the relationship between students’ subjectively perceived social status and the likelihood of participation in these different internationalisation activities. As can be observed in , students who self-identify as working class are significantly more likely to participate in some internationalisation at home initiatives compared to students who perceive themselves as belonging to the middle- or upper-class. In particular, a statistically significant correlation between students’ working class status and the likelihood of participation in guest lectures of international teachers, international Summer schools at home, and an international week with a foreign partner can be observed.

Regarding students’ migration background, it is interesting to notice that degree mobile students are significantly more likely to participate in internationalisation activities compared to the majority population. This probably reflects their international orientation – as they decided to study abroad for several years. The results for students with a migration background are less pronounced, but indicate that there are certain activities at home as well as abroad they are significantly more likely to engage in. In particular, the findings indicate that students with a migration background are more likely to participate in an international week with a foreign partner, Spring/Winter schools, activities organised by international student organisations, intercultural workshops, and to become a buddy of an international student. Considering internationalisation activities abroad, they are more likely to participate in short-term international activities (1-3 months) such as exchanges, research, fieldwork and internships, taking a course in a nearby foreign institution compared to the majority native student population, as well as in long-term international activities such as studying a full degree abroad, and to participate in an international exchange or internship.

Interaction effects

In a final analytical step, we investigated also interaction effects between socio-economic status and migration background, in order to probe deeper into the results presented in the previous section. As can be observed in , students from the majority population with no parent(s) who obtained a higher education degree are significantly less likely to participate in all internationalisation activities, and in particular they are significantly less likely to participate in international guest lectures, Winter/Spring schools and a study abroad information day at their home institution, and an international Summer school, language course, volunteering, or short-term research, exchanges or internships abroad. Interestingly, the results indicate that the significant higher likelihood of students with a migration background to participate in certain internationalisation activities is largely explained by the interaction between their migration background and socio-economic status. Particularly students with a migration background who have at least one parent with a higher education degree are more likely to participate in internationalisation activities. In contrast, students with a migration background and no higher educated parent are only more likely to study a full degree abroad compared to students from higher socio-economic backgrounds and the majority population.

Table 3. Interaction effects between socio-economic status and migration background, odds ratios (ref: at least one parent with a higher education degree x majority population).

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we focused on social selectivity in higher education students’ participation in internationalisation activities abroad and at home, adding a sociological perspective to the international higher education literature. In line with larger sociological studies which suggest that students with different socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds might participate in different activities throughout their higher education programme (e.g. Pascarella et al. Citation2004; Armstrong and Hamilton Citation2013), the presented findings underline the importance of acknowledging the diversity of student populations when designing internationalisation activities, as significant differences between social groups can be observed. For years, the focus of HEIs internationalisation strategies has been on encouraging mobility abroad, as the number of mobile students has often been interpreted as a proxy of an institution’s level of internationalisation. Nevertheless, our findings show the need of providing a wider array of internationalisation activities in order to cover the needs of the whole student body, independently of their social background. However, our results also indicate that only broadening activities will not be sufficient. After all, students from lower socio-economic backgrounds showed to be less likely to participate in any internationalisation activities, and they also indicate the importance of considering multiple social markers when analysing decision-making processes to participate in internationalisation activities. Students with a migration background, for example, show to be more inclined to participate in certain internationalisation activities, but once socio-economic status is taken into account, it becomes clear that also here, socio-economic background plays a crucial role. The persistent role of socio-economic background that comes forward in our analysis indicates the need for more solid theoretically informed empirical – qualitative and quantitative – research that uncovers the mechanisms explaining the lower likelihood of these students to participate in internationalisation activities, beyond the associations that we uncovered in this paper which, however, is a necessary first step. Sociological studies such as those from Diane Reay (Reay et al. Citation2001, Citation2005; Reay Citation2021) can be a useful starting point, as they indicate that this difference in participation is not only limited to internationalisation activities, but that working class students are less likely to participate in any extra-curricular activity. Consequently, future research should particularly try to reveal ‘the subjective processes that lie behind the figures’ (Reay Citation2021, 54), focusing on both students’ subjective experiences and structural barriers they encounter throughout higher education. Following classical sociological theories – in particular Bourdieu, it is likely that differences in economic, cultural and social capital between socio-economic groups can partly explain differences in participation. After all, these three forms of capital have shown to influence students’ navigation through higher education (see e.g. Stuber Citation2011; Reay Citation2021; Watson Citation2013; Bathmaker, Ingram, and Waller Citation2013), and are consequently likely also related to students’ (non-) participation in internationalisation activities. Next to having been disposed to a different socialisation process compared to higher socio-economic backgrounds, wherein international activities might not have prominently figured, students from lower socio-economic background are probably also more likely to experience practical barriers. For example, it is plausible that students from lower socio-economic backgrounds are less likely to receive information on internationalisation activities – both at home and abroad, might attach less value to them, or simply, they might be too costly because of the fact that they often have to work during their studies (see e.g. Hurst Citation2018; Armstrong and Hamilton Citation2013). Furthermore, internationalisation at home activities such as Summer schools and Winter schools are often offered outside of the formal curriculum and study programme, and hence be incompatible with some students’ financial situation and time schedule. However, all the potential explanations outlined above need to be investigated in future studies.

Naturally, our study also has some limitations. First, the geographical scope of our study was somewhat limited, as it only concerned three HEIs in two countries. Future research, focusing on a wider variety of countries and institutions would be extremely helpful for further advancing our understanding of the dynamics at play. Second, although our list of internationalisation activities was extensive, there are other internationalisation activities that were not included in this study, such as collaborative research or twinning. Third, our survey might also suffer from some self-selection bias. The invitation to the survey indicated that it concerned a survey on internationalisation, which might attract a specific sub-group of higher education students that are principally already more interested in the subject.

In sum, our findings indicate that the social composition of student populations needs to be taken into account when designing internationalisation strategies. To this respect, we encourage higher education leaders to take a closer look to internationalisation at home actions, to focus on the internationalisation of the curriculum (Leask Citation2015) and beyond. When doing so, however, it is important to incorporate such activities within the formal study schedule instead of rewarding study credits for participation in activities that are organised in students’ leisure time and/or holidays. This recommendation is also supported by sociological work which indicates that only a minority of working-class young students participate in out-of-school activities and that the best place to capture the attention of working-class students is within classrooms, not through extracurricular activities (Reay Citation2017). Reay’s work also points out that working-class students often prioritise academic work instead of social activities in the first year. In sum, the barriers to participation in the commonly applied scenario of extra-curricular activities is likely much higher for students from lower socio-economic backgrounds. To that respect, more efforts should be made by institutions to provide equitable and inclusive internationalisation activities. This also includes different mobility opportunities abroad accessible to all students, independently of their socio-economic status. Moreover, information about the traditional mobility schemes should be more targeted, addressing for example underprivileged students’ fear of prolonging their studies through mobility and with more information on its benefits to raise readiness to go abroad (Lörz, Netz, and Quast Citation2016). In addition, we also argue for a better nexus between research and practice: if inclusive internationalisation strategies are to be truly inclusive, it is essential to first identify the internationalisation activities that different social groups of students are interested in, by asking them instead of sailing blindly. Finally, we also question the normativity that is often inherent to inclusive internationalisation strategies: is it really necessary for all students to have international experiences? If different groups of students have different expectations regarding their education and future jobs, no interest in such activities should not be interpreted as a deficiency (Stuber Citation2011).

Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (25.8 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Araz Khajarian for supporting the preparation of the survey.

Ethics: This research project was reviewed by the ethical board of Tilburg University (EC-2019.36). All respondents gave their informed consent to use the data for research purposes before accessing the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

A data package, containing the base version of the fully anonymised data as well as the working version, syntaxes and anonymised questionnaires of the research project is stored at Surfdrive. This data package is available upon simple request and will be accessible for a minimum of 10 years.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2092308)

References

- Ahmad, Akhlaq. 2020. “Ethnic Discrimination Against Second-generation Immigrants in Hiring: Empirical Evidence from a Correspondence Test.” European Societies, 1–23. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1822536.

- Almeida, Joana, Sue Robson, Marilia Morosini, and Caroline Baranzeli. 2019. “Understanding Internationalization at Home: Perspectives from the Global North and South.” European Educational Research Journal 18 (2): 200–17. doi:10.1177/1474904118807537.

- Armstrong, Elizabeth A., and Laura T. Hamilton. 2013. Paying for the Party: How College Maintains Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bathmaker, Ann-Marie, Nicola Ingram, and Richard Waller. 2013. “Higher Education, Social Class and the Mobilisation of Capitals: Recognising and Playing the Game.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (5-6): 723–43. doi:10.1080/01425692.2013.816041.

- Beelen, Jos, and Elspeth Jones. 2015. “Europe Calling: A New Definition for Internationalization at Home.” International Higher Education 83: 12–3.

- Beelen, Jos, and Elspeth Jones. 2018. “Internationalization at Home.” In Encyclopedia of International Higher Education Systems and Institutions, edited by Pedro Nuno Teixeira and Jung Cheol Shin, 1–4. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Blommaert, Lieselotte, Marcel Coenders, and Frank van Tubergen. 2014. “Discrimination of Arabic-Named Applicants in the Netherlands: An Internet-Based Field Experiment Examining Different Phases in Online Recruitment Procedures.” Social Forces 92 (3): 957–82. doi:10.1093/sf/sot124.

- Christie, Hazel, Viviene E. Cree, Eve Mullins, and Lyn Tett. 2018. “‘University Opened Up So Many Doors for Me’: The Personal and Professional Development of Graduates from Non-traditional Backgrounds.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (11): 1938–48. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1294577.

- De Wit, Hans, Fiona Hunter, Laura Howard, and Eva Egron-Polak. 2015. Internationalisation of Higher Education. Brussels: European Union.

- De Wit, Hans, and Elspeth Jones. 2018. “Inclusive Internationalization: Improving Access and Equity.” International Higher Education 94: 16–8.

- D'Hooge, Lorenzo. 2019. Mind Over Matter: Causes and Consequences of Class Discordance. Alblasserdam: Ridderprint.

- Feliciano, Cynthia, and Yader R. Lanuza. 2017. “An Immigrant Paradox? Contextual Attainment and Intergenerational Educational Mobility.” American Sociological Review 82 (1): 211–41. doi:10.1177/0003122416684777.

- Glass, Chris R. 2012. “Educational Experiences Associated With International Students’ Learning, Development, and Positive Perceptions of Campus Climate.” Journal of Studies in International Education 16 (3): 228–51. doi:10.1177/1028315311426783.

- Hurst, Allison L. 2018. “Classed Outcomes: How Class Differentiates the Careers of Liberal Arts College Graduates in the US.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (8): 1075–93. doi:10.1080/01425692.2018.1455495.

- Janebova, Eva, and Christopher J. Johnstone. 2021. “Mapping the Dimensions of Inclusive Internationalization.” In Inequalities in Study Abroad and Student Mobility. Navigating Challenges and Future Directions, edited by Suzan Kommers, and Krishna Bista, 115–124. New York: Routledge.

- Jon, Jae-Eun. 2013. “Realizing Internationalization at Home in Korean Higher Education: Promoting Domestic Students’ Interaction with International Students and Intercultural Competence.” Journal of Studies in International Education 17 (4): 455–70. doi:10.1177/1028315312468329.

- Khattab, Nabil. 2018. “Ethnicity and Higher Education: The Role of Aspirations, Expectations and Beliefs in Overcoming Disadvantage.” Ethnicities 18 (4): 457–70. doi:10.1177/1468796818777545.

- Knight, Jane. 2012. “Student Mobility and Internationalisation: Trends and Tribulations.” Research in Comparative and International Education 7: 20–33.

- Leask, Betty. 2009. “Using Formal and Informal Curricula to Improve Interactions Between Home and International Students.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (2): 205–21. doi:10.1177/1028315308329786.

- Leask, B. 2015. Internationalizing the Curriculum. London: Routledge.

- Li, Yaojun. 2018. “Against the Odds? – A Study of Educational Attainment and Labour Market Position of the Second-Generation Ethnic Minority Members in the UK.” Ethnicities 18 (4): 471–95. doi:10.1177/1468796818777546.

- Lörz, M., N. Netz, and H. Quast. 2016. “Why Do Students from Underprivileged Families Less Often Intend to Study Abroad?” Higher Education 72 (2): 153–174. doi:10.1007/s10734-015-9943-1.

- Massey, Douglas S., and Kristin E. Espinosa. 1997. “What's Driving Mexico-U.S. Migration? A Theoretical, Empirical, and Policy Analysis.” American Journal of Sociology 102 (4): 939–99.

- Middendorff, Elke, Beate Apolinarski, Jonas Poskowsky, Maren Kandulla, and Nicolai Netz. 2013. Die wirtschaftliche und soziale Lage der Studierenden in Deutschland 2012. Berlin: BMBF.

- Murphy-Lejeune, Elizabeth. 2002. Student Mobility and Narrative in Europe. The New Strangers. London: Routledge.

- Netz, Nicolai, Michelle Barker, Steve Entrich, and Daniel Klasik. 2021. “Socio-demographics: A Global Overview of Inequalities in Education Abroad Participation.” In Education Abroad. Bridging Scholarship and Practice, edited by Anthony Ogden, Bernhard Streitwieser, and Christof Van Mol, 28–42. Oxon: Routledge.

- Netz, Nicolai, and Claudia Finger. 2016. “New Horizontal Inequalities in German Higher Education? Social Selectivity of Studying Abroad Between 1991 and 2012.” Sociology of Education 89 (2): 79–98. doi:10.1177/0038040715627196.

- Netz, Nicolai, and Andreas Sarcletti. 2021. “(Warum) beeinflusst ein Migrationshintergrund die Auslandsstudienabsicht?” In Migration, Mobilität und soziale Ungleichheit in der Hochschulbildung, edited by Monika Jungbauer-Gans, and Anja Gottburgsen, 103–36. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Ogden, Anthony Charles, Bernhard Streitwieser, and Christof Van Mol. 2021. Education Abroad. Bridging Scholarship and Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Pascarella, Ernest T., Christopher T. Pierson, Gregory C. Wolniak, and Patrick T. Terenzini. 2004. “First-Generation College Students. Additional Evidence on College Experiences and Outcomes.” The Journal of Higher Education 75 (3): 249–84.

- Perez-Encinas, Adriana, Jesus Rodriguez-Pomeda, and Hans de Wit. 2020. “Factors Influencing Student Mobility: A Comparative European Study.” Studies in Higher Education, 1–14. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1725873.

- Reay, D. 2017. Miseducation: Inequality, Education, and the Working Classes. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Reay, Diane. 2021. “The Working Classes and Higher Education: Meritocratic Fallacies of Upward Mobility in the United Kingdom.” European Journal of Education 56 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1111/ejed.12438.

- Reay, Diane, Miriam E. David, and Stephen Ball. 2005. Degrees of Choice. Class, Race, Gender and Higher Education. Stoke on Trent: Trentham Books.

- Reay, Diane, Jacqueline Davies, Miriam David, and Stephen J. Ball. 2001. “Choices of Degree or Degrees of Choice? Class, ‘Race’ and the Higher Education Choice Process.” Sociology 35 (4): 855–74.

- Schendel, Rebecca, and Tristan McCowan. 2016. “Expanding Higher Education Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: The Challenges of Equity and Quality.” Higher Education 72 (4): 407–11. doi:10.1007/s10734-016-0028-6.

- Sennett, Richard, and Jonathan Cobb. 1973. The Hidden Injuries of Class. New York: Vintage.

- Soria, Krista M., and Jordan Troisi. 2014. “Internationalization at Home Alternatives to Study Abroad:Implications for Students’ Development of Global, International, and Intercultural Competencies.” Journal of Studies in International Education 18 (3): 261–80. doi:10.1177/1028315313496572.

- Stevens, Mitchell L., Elizabeth A. Armstrong, and Richard Arum. 2008. “Sieve, Incubator, Temple, Hub: Empirical and Theoretical Advances in the Sociology of Higher Education.” Annual Review of Sociology 34 (1): 127–51. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134737.

- Stuber, J. M. 2006. “Talk of Class: The Discursive Repertoires of White Working- and Upper-Middle-Class College Students.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 35 (3): 285–318. doi:10.1177/0891241605283569.

- Stuber, Jenny M. 2011. Inside the College Gates: How Class and Culture Matter in Higher Education. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

- VLOR. 2015. Advies over de registratie van kansengroepen in het hoger onderwijs. Brussel: Vlaamse Onderwijsraad.

- Walpole, MaryBeth. 2003. “Socioeconomic Status and College: How SES Affects College Experiences and Outcomes.” The Review of Higher Education 27 (1): 45–73.

- Watkins, Heather, and Roy Smith. 2018. “Thinking Globally, Working Locally: Employability and Internationalization at Home.” Journal of Studies in International Education 22 (3): 210–24. doi:10.1177/1028315317751686.

- Watson, Jo. 2013. “Profitable Portfolios: Capital That Counts in Higher Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 34 (3): 412–30. doi:10.1080/01425692.2012.710005.

- Wilbur, Tabitha G., and Vincent J. Roscigno. 2016. “First-generation Disadvantage and College Enrollment/Completion.” Socius 2: 2378023116664351. doi:10.1177/2378023116664351.

- Zschirnt, Eva. 2020. “Evidence of Hiring Discrimination Against the Second Generation: Results from a Correspondence Test in the Swiss Labour Market.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 21 (2): 563–85. doi:10.1007/s12134-019-00664-1.

- Zschirnt, Eva, and Didier Ruedin. 2016. “Ethnic Discrimination in Hiring Decisions: A Meta-analysis of Correspondence Tests 1990–2015.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (7): 1115–34. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1133279.