ABSTRACT

Post-pandemic, many universities are seeking ways to better engage students and support them to stay with and succeed in their studies. Immersive scheduling, whereby students complete units over shorter time periods than the traditional 12–15 week semester or trimester, may be a way to do this and improve academic outcomes at scale. This paper focuses on the impact of an immersive scheduling model at a public Australian university where higher education is being delivered over 6-week terms using active learning pedagogy. Student grades (N = 9,655) and unit feedback survey responses (N = 3,267) were collected from a suite of non-award pathways, sub-bachelor and Bachelor units offered in the immersive scheduling model in 2021 and the traditional trimester model in 2019. Results were compared across the two models for commencing, continuing, pathways, undergraduate, on-campus, online and mixed-mode students. Success rates improved in the immersive scheduling model compared to the traditional trimester model to a statistically significant degree for all cohorts, with particularly strong achievement enhancements observed for online students. These improvements exceeded results for a control group of units delivered in the traditional model in both years. Strong improvements in the pathways units, which were delivered using active learning pedagogy before and after the implementation of immersive scheduling, demonstrate that the more focused way of learning created through the model may be an important factor underpinning improved academic success. High levels of unit and teaching satisfaction were maintained in the immersively-scheduled units, indicating that the model supports high student satisfaction.

Introduction

The transformation of higher education (HE) from ‘elite’ to ‘mass’ in western contexts has heightened a responsibility on the part of HE institutions to explore how they can better support the academic success of an increasingly diverse range of students (Thomas, Kift, and Shah Citation2021). This responsibility has been further complicated by COVID-19, which has seen a rising number of students expressing preferences for more flexible modes of study (Horstmann Citation2022; Kelly Citation2021).

One way that universities can seek to bolster student success in this changing environment is by revisiting the model they use to deliver units and courses. HE has traditionally been delivered through a semester or trimester model whereby full-time students complete more than three subjects concurrently over 12–15 weeks. Shorter delivery models are a non-traditional alternative that have recently attracted increasing interest in Australia, the United Kingdom (UK) and North America (Nerantzi and Chatzidamianos Citation2020; Williams Citation2023). The terminology, duration and teaching approaches used in these models vary, with durations ranging from 2 to 10 weeks and study loads varying from 1–2 units (Davies Citation2006; Samarawickrema et al. Citation2022). Terms used in the literature to describe these models – often interchangeably (see Buck and Tyrrell Citation2022; Turner, Webb, and Cotton Citation2021) – include ‘intensive’, ‘compressed’, ‘accelerated’ and ‘block’ (Davies Citation2006). The latter term has recently become popular for models where students complete one unit at a time over 4–5 week periods (Loton et al. Citation2022; Williams Citation2023).

In contrast to these more typical block models, the delivery model under investigation here, known as the Southern Cross Model (SCM), allows students to study up to two units at a time over 6-week teaching terms. It also involves a specific application of active learning pedagogy across the institution, encompassing the design of: interactive online modules; guided, active classes; and authentic, interlinked assessments (see Goode, Nieuwoudt, and Roche Citation2022; Roche, Wilson, and Goode Citation2022). This paper adopts the term ‘immersive scheduling’ (Turner, Webb, and Cotton Citation2021) or more simply ‘immersive model’ as an umbrella term that may encompass one-unit-at-a-time block models as well as two-unit-at-a-time models such as the SCM.

Although there is an emerging body of work concerning block delivery over 4-week periods (e.g. Ambler, Solomonides, and Smallridge Citation2021; Buck and Tyrrell Citation2022; Jackson et al. Citation2022; Loton et al. Citation2022), there are fewer studies on immersive models that are similar to the SCM in duration and full-time study load (see Goode, Nieuwoudt, and Roche Citation2022; Goode, Syme, and Nieuwoudt Citation2022; Walsh, Sanders, and Gadgil Citation2019). Differing approaches to scheduling and pedagogy are likely to provide students with contrasting study experiences (Davies Citation2006), and the SCM may offer an effective compromise between traditional semester-based learning and one-unit-at-a-time block learning. Moreover, as Loton et al. (Citation2022) note in their recent analysis of block model learning, there is a need to evaluate new learning models through comparing pre- and post-implementation data across large samples encompassing a range of disciplines and study levels.

Responding to these issues, this paper aims to explore two key questions:

How has the introduction of a 6-week immersive, active learning model affected student achievement and feedback in comparison to a traditional trimester model of learning at a public Australian university?

Do effects on student achievement and feedback differ between cohorts across course level (pathwaysFootnote1/undergraduate), attendance mode (external/internal/mixed) or student group (commencingFootnote2/continuing)?

This paper provides an analysis of aggregated student performance data (N = 9,655) as well as student feedback on overall teaching and overall subject (hereafter unit) satisfaction (N = 3,267) (see also Goode et al. Citation2022). It compares outcomes in a pilot year of the immersive model with those from the traditional delivery model, and for the domestic cohorts identified above.Footnote3 The pathways cohort enables additional insight into the impact of immersive scheduling specifically, as the pathways programme was delivered with similar pedagogical approaches both before and after the introduction of the immersive model (Nieuwoudt Citation2018; Syme et al. Citation2022). To aid interpretation of the performance data, final grades from a control group of units which remained in the traditional trimester model are also analysed.

Review of the literature

Block and immersive delivery models

While more commonly used in postgraduate education (Harvey, Power, and Wilson Citation2017), shorter delivery models – including block, immersive and intensive models – are now used across undergraduate and postgraduate courses at Victoria University (VU), Australia, as well as some small-scale liberal arts colleges in North America (Loton et al. Citation2022). Recent research in the UK and Australia has demonstrated that, overall, students in immersive model units achieve significantly higher marks (Goode, Syme, and Nieuwoudt Citation2022; Loton et al. Citation2022; Turner, Webb, and Cotton Citation2021). Some analyses also show that immersive models affect particular cohorts more strongly, with pronounced achievement enhancements observed for males (Turner, Webb, and Cotton Citation2021) and students from low socio-economic status (SES) areas or non-English speaking backgrounds (Winchester, Klein, and Sinnayah Citation2021). Building on these findings, the present research examines the impact of an immersive model across enrolment categories of broad interest to education providers internationally: pathways/undergraduate, commencing/continuing and external/internal/mixed-mode.

The SCM draws on cognitive load theory, which purports that the architecture of human cognitive processes has a finite capacity constraint that may be overloaded when engaged in tasks of high complexity or in multiple tasks, leading to decreases in cognitive performance (Sweller Citation1988) and potentially poorer academic outcomes (Mason, Seton, and Cooper Citation2016). Countering concerns that immersive models compromise learning (see Dixon and O’Gorman Citation2020; Lutes and Davies Citation2018), Faught, Law, and Zahradnik (Citation2016) observed similar knowledge retention among health sciences students in accelerated and traditional formats at 3, 6 and 12 months past a unit of study. In terms of post-study outcomes, Eames, Luttman, and Parker (Citation2018) found that alumni from immersively-scheduled accounting programmes were just as successful in passing professional accreditation exams as alumni from traditional-length programmes.

Various studies have reported high levels of student satisfaction with immersive models (Richmond et al. Citation2015; Turner, Webb, and Cotton Citation2021). Evidence indicates that the enhanced focus enabled by these models raises students’ confidence (Goode, Syme, and Nieuwoudt Citation2022; Lee and Horsfall Citation2010) and can assist them with achieving a better balance between study and other commitments (Burton and Nesbit Citation2002; Zhang and Cetinich Citation2022). In some research, however, student satisfaction has been mixed or less positive. Analysis of over 15,000 end-of-unit ratings at an Australian university revealed that while teaching satisfaction increased in a 4-week block model, unit satisfaction did not (Loton et al. Citation2022). A study of preservice teachers’ perceptions of shortened units found that students were generally dissatisfied; however, it was also concluded that the unit designs did not appear to reflect best practice in shorter-mode learning (Colclasure et al. Citation2018). This suggests that the pedagogical design of immersive model units may be a key factor underpinning their success.

Active and guided learning

Immersive models typically represent more than a calendar change in content delivery, and often draw on active learning pedagogies. There is strong support for active learning pedagogies in the teaching and learning literature (Smith and Baik Citation2021). Such approaches emphasise that learning is facilitated primarily through activities such as practicals, discussions or engaging in problem-solving, where students can test their hypothetical mental models of the world and develop their knowledge and skills further than passive listening allows (Freeman et al. Citation2014; Willingham Citation2017). Several large studies have reinforced the advantages of active learning approaches over didactic techniques (see Freeman et al. Citation2014 for a review of over 200 studies; and Schneider and Preckel Citation2017 for a systematic review of meta-analyses sampling some 2 million students). In order to maximise success, however, active learning experiences should remain guided ones.

Evidence suggests that providing students with clear and careful guidance for their activities and interactions is a vital element of successful teaching (Cho, Park, and Lee Citation2021; Mayer Citation2004; Schneider and Preckel Citation2017). Effective guidance offers scaffolds for students’ confidence and development, while challenging them and activating their intellectual capacity (Goode, Syme, and Nieuwoudt Citation2022; Hellmundt and Baker Citation2017). In converged or blended deliveries involving both face-to-face and online learning, it is increasingly important for teachers to function as curators and guides rather than content creators or knowledge transmitters (Kellermann Citation2021; Wolfe and Andrews Citation2014). This means, for example, packaging unit content into engaging chunks of materials and activities in learning sites to complement in-class experiences; this approach can provide students with greater flexibility in time and place for their learning (Joyner and Isbell Citation2021) while providing interactive and aligned learning experiences that enhance engagement (Goode, Syme, and Nieuwoudt Citation2022) and enable regular opportunities for feedback (Hattie and Timperley Citation2007). The core principles of focused, active and guided learning underpin the SCM.

The Southern Cross Model

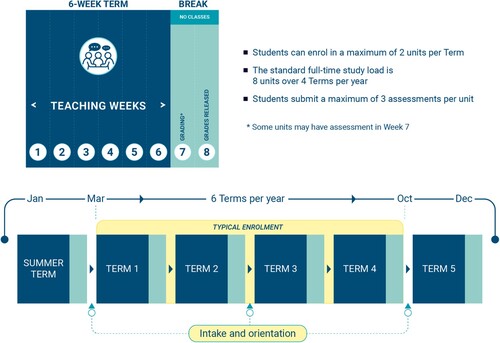

The SCM structures the academic calendar into six, 6-week teaching terms and reduces the number of concurrent subjects from four units per 13-week trimester to two units per 6-week term (see ). Full-time students typically complete eight units across four terms in a year, and can thereby complete the same number of credit points and achieve the same learning outcomes with the same volume of learning, as they could in the traditional trimester model.

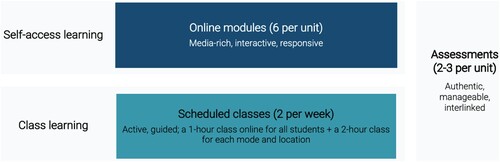

The converged design of the SCM involves two main forms of learning alongside the assessment tasks: self-access learning through online modules; and class learning through live, scheduled workshops and tutorials (see ). The online modules are designed to provide students with learning experiences that are: media rich, drawing on a variety of instructional approaches beyond text-based materials; interactive, requiring responses from learners in the form of reflection, discussion, quizzes, etc.; and responsive, providing students with feedback that they can use to gauge their learning, and teachers with an indication of students’ progress (for examples see Goode, Nieuwoudt, and Roche Citation2022). Class learning involves activities such as peer collaboration and discussion, practice, simulations and problem-solving, under the guidance of a teacher (Roche, Wilson, and Goode Citation2022). Assessments are designed to be authentic, interlinked and manageable across a 6-week term. Notably, a subset of units reported on in this study, the pathways units, were designed in line with these principles – active learning pedagogy using interactive online materials and authentic assessments – both before and after the implementation of the SCM.

Methodology

Unit selection

This retrospective observational study drew on quantitative institutional data to compare student academic performance and satisfaction between the traditional (pre-pandemic) trimester model in 2019 and the pilot year of the immersive model in 2021. The study was approved by the institution’s Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number 2022/054.

Three groups of units were identified for analysis. Group 1 (matched-pairs) comprises the 16 units that were delivered in trimesters in 2019 and then in terms in 2021, including: five non-award pathways units covering academic communication, science and mathematics; and 11 undergraduate coursework units spanning engineering, education, business, tourism and accounting. These matched-pairs maintained the same unit codes, aims and learning outcomes across both models. The pathways units also maintained the same pedagogical approach, with active learning, interactive online materials and authentic assessments.

Group 2 comprises six core units offered in the first year of the Bachelor of Business in trimesters in 2019 and seven core units offered in the first or second year of the Bachelor of Business and Enterprise.Footnote4 As the Bachelor of Business and Enterprise replaced the Bachelor of Business in 2021, group 2 units are not matched across the years. However, given that the design of the immersive units was so comprehensively guided by the principles of the SCM and that Business and Enterprise was the only Bachelor’s degree to be offered in the immersive model in the pilot year, this second unit group was considered useful for generating insights into how the model can affect undergraduate student performance and satisfaction.

A third control group of units was also analysed, comprising 33 first-year undergraduate health units offered in trimesters in 2019 and 2021. These units had reasonably stable domestic enrolments across both years, and as first-year units aimed at commencing students they generally reflect the study level of the units included in the traditional/immersive groups. The university system housing the control group data did not capture unit feedback for these units; therefore, only performance data is reported on for this group.

Data collection and sampling

Two sets of de-identified data were obtained from the University’s data systems. The first set contained performance observations in the form of final grades across both years. The second set comprised satisfaction observations in the form of responses to the University’s standard Unit Feedback Survey (administered as a 5-point Likert scale survey after every unit offering before the release of final grades).

Data were excluded if they did not meet the criteria for the unit groupings described above. Performance observations were further excluded if the student had withdrawn before Census Date (the date at which fees are applied to all enrolled students) or if they had not been awarded a final grade. The final performance observations included fail grades (Fail, Absent Fail, or Withdrawn Fail)Footnote5 or passing grades (Pass, Credit, Distinction, or High Distinction). The filtering resulted in five samples, as shown in .

Table 1. Study samples.

Data analysis

Data were uploaded into STATA 17.0 for preparation and analysis. Samples 1 and 4 were further separated into cohorts across course level, attendance mode and student group. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study populations.

The grades data were dichotomised into pass (success) and fail frequencies across both years for each cohort. These frequencies were tested for significant change from 2019 to 2021 using Pearson’s chi-square test (see Field Citation2018) and Cramér’s V for effect size. It should be noted that the interpretation of Cramér’s V is not standardised: for example, a value > 0.15 is considered strong by Akoglu (Citation2018) but immaterial by McHugh (Citation2018). We adopt Akoglu’s (Citation2018) criteria for effect size, where >0.05 is considered weak, >0.1 moderate, >0.15 strong and >0.25 very strong.

Responses to two items in the Unit Feedback Survey were isolated to explore overall student satisfaction with the unit: ‘Overall, I am satisfied with this unit’; and overall satisfaction with teaching: ‘Overall, I am satisfied with the teaching in this unit’. The data were dichotomised into two values: agreement (ratings of 5 strongly agree or 4 agree); and non-agreement (ratings of 3 average, 2 disagree or 1 strongly disagree). The dichotomised data were analysed using Pearson’s chi-square tests and Cramér's V.

Results

Academic performance

shows the count of grades awarded and the success rate for each cohort in 2019 and 2021, as well as the increase between years, the chi-square test results and Cramér’s V. The number of students decreased in all cohorts from 2019 to 2021, with the smallest decrease occurring for external students (5.04%) and the largest decreases occurring for internal (47.4%) and mixed-mode students (49.27%).

Table 2. Descriptive and inferential statistics for academic performance, 2019 and 2021.

Chi-square tests on the dichotomised pass/fail data show that there were statistically significant improvements in success rates in the immersive model for all cohorts. Significance was at the 0.1% level for all groups except undergraduate and mixed-mode students in the matched-pair sample, at the 1% level. Cramér’s V outputs reveal effect sizes for the matched-pair and undergraduate business cohorts ranging from 0.09 to 0.28 (weak to very strong). We note improvement in the control group’s outcomes, but the improvement (and effect size) is the weakest of the three samples: a 6.87% improvement (Cramér’s V 0.08) compared to a 17.74% improvement across sample 1 (Cramér’s V 0.19) and similar results for sample 2.

The improvement for pathways students was stronger than sample 1 overall even though the only major change was to their scheduling, and not the pedagogical approach. The improvement for external (online) students was the largest of all cohorts.

Student satisfaction

shows the count, percentage agreement, change in agreement between years, chi-square test results and Cramér’s V for unit satisfaction in 2019 and 2021. provides the equivalent data for teaching satisfaction. The sample 4 survey response rate was 29.37% in 2019 and 43.25% in 2021. The sample 5 response rate was 20.72% in 2019 and 44.80% in 2021.Footnote6

Table 3. Descriptive and inferential statistics for overall unit satisfaction, 2019 and 2021.

Table 4. Descriptive and inferential statistics for overall teaching satisfaction, 2019 and 2021

Unit satisfaction was slightly higher for sample 5 (undergraduate business units) in the immersive model: a 7.69% improvement, significant at 5% and moderate Cramér’s V. There were no other significant changes to the already high levels of satisfaction for either units or teaching.

Discussion

The current study sought to evaluate the extent to which the implementation of an immersive scheduling model improved student academic performance and feedback during a pilot year of implementation at a public Australian university. Student grades and satisfaction observations were collected from a suite of non-award pathways, sub-bachelor and Bachelor units delivered in 6-week terms in 2021 and compared with data from 13-week trimesters in 2019.

The first key finding from this study is that student success rates increased in the immersive model to a statistically significant degree. The degree of statistical significance was 0.1% for all cohorts, except for the undergraduate and mixed-mode students in the matched-pair sample, which were significant at the 1% level. These strong achievement improvements are consistent with results from 4-week block models at universities in Australia (Loton et al. Citation2022) and in the UK (Turner, Webb, and Cotton Citation2021). Diverging from these prior studies, however, the present research included a control group of first-year undergraduate units that stayed in the traditional trimester model for the duration of the study. Although academic success in these units increased by 6.87%, much larger increases were observed in the undergraduate business sample (16.61%) and the matched-pair sample overall (17.74%). The effect size was also weak for the traditional model units, compared with strong effects in the immersive model samples overall (Akoglu Citation2018). The data therefore support that the immersive model appears to be a key factor driving significant improvements in academic performance for the cohorts in this study.

Nonetheless, the statistically significant increase in success rate for the control group indicates that factors unrelated to the immersive model may have contributed to the strong results observed in the immersive model samples. Perhaps most notably, 2021 was the second year of COVID-19 restrictions, involving international and state border restrictions, extended periods of lockdown and enforced online learning up to October. Despite these constraining circumstances, evidence suggests that both benefits and challenges resulted; it appears that some HE students experienced added flexibility that supported their ability to continue learning, while others – particularly students from multiple categories of disadvantage – were more negatively affected (Mercer-Mapstone et al. Citation2022). However, research has also found that being from a minoritised or vulnerable group was not a reliable explanatory factor for lower confidence in one’s ability to learn successfully during the pandemic (Bartolic et al. Citation2022). While these prior studies do not provide conclusive indications about the impacts of COVID-19 on academic achievement, we speculate that improved teaching strategies for pandemic HE and adjusted expectations among students may partially underpin the success rate improvements found across all samples in 2021, in both traditional and immersive models. Additionally, during the second data collection period the institution implemented a time-bound change to its special consideration process, whereby if students disclosed that they or a person in their care were impacted by COVID-19 then an automatic assessment deadline extension was granted. It is possible that this pandemic-related accommodation somewhat bolstered student performance for both the traditional and immersive model cohorts; however, due to how that information is recorded in university systems, it is not possible to account for the magnitude of the impact on grades.

Another issue relevant to the interpretation of the data is the expansive approach to curriculum renewal in the immersive model. The implementation of the SCM involved a multifaceted approach to curriculum transformation, and as such enhancements in student outcomes could potentially be driven by various aspects of the immersive model: scheduling, curriculum and/or pedagogical changes. Academic performance enhancements have been observed in approaches that apply active learning pedagogies (Freeman et al. Citation2014) and in delivery models that combine active learning and immersive scheduling (Loton et al. Citation2022).

While the intertwined nature of these factors in the SCM means that it is not possible to conclusively disentangle their impacts, the results obtained in the pathways units provide important insight in this regard. These units – which the lead author taught into in 2019 and 2020 – were delivered using active learning pedagogies, authentic approaches to assessment and online interactive learning materials in the traditional model, prior to the introduction of immersive scheduling (as described by Nieuwoudt Citation2018; Syme et al. Citation2022). While additional constructive alignment and minor changes to assessment occurred for the new model, the introduction of immersive scheduling was the major change for this cohort. The highly statistically significant increase in success that followed (19.23%) therefore suggests that the more focused way of learning created through the model, with fewer competing cognitive load demands, may be an important factor underpinning improved academic success. Supporting this, reduced cognitive load has indeed been postulated as an explanation for heightened student outcomes in previous studies of immersive models (Richmond et al. Citation2015; Turner, Webb, and Cotton Citation2021).

Considering both the literature on effective university teaching (see Roche, Wilson, and Goode Citation2022) and the results obtained in this study, we therefore concur with research which posits that effective and holistic pedagogical practice likely mediates the impact of immersive scheduling on student outcomes (Buck and Tyrrell Citation2022). In other words, combining immersive scheduling with active learning approaches may amplify positive impacts. Qualitative investigations align with this conclusion; both pathways and undergraduate students have indicated that the carefully considered design of interactive and responsive online materials complemented by dialogic classroom teaching were key pedagogical attributes underpinning their learning and success in an immersive model (Goode, Nieuwoudt, and Roche Citation2022; Goode, Syme, and Nieuwoudt Citation2022).

Another important contribution of this study is to demonstrate the efficacy of a 6-week, two-unit-at-a-time delivery model, where there is more flexibility in choice of study load compared to shorter block or one-unit-at-a-time models. Some sources contend that the more typical block model approach may not allow for knowledge retention strategies such as interleaving, where learners can switch focus between different topics, or spaced learning, where learning is spread over longer periods of time instead of ‘crammed’ into short bursts (Lodge Citation2018). The SCM may represent an effective compromise between the traditional four-unit-at-a-time semester or trimester model, and the one-unit-at-a-time block model.

An additional key finding from this research is that the most pronounced increase in success in the immersive model occurred for external mode students. Cognitive load theory suggests that learning online via interactive materials can bring added challenges for understanding and retaining information (Kalyuga Citation2012; Skulmowski and Xu Citation2022). This may be due to a variety of factors, including the multimedia nature of the content (Kalyuga Citation2012). Online learners also tend to be older than their on-campus counterparts and are often juggling multiple responsibilities such as work and family (Stone and O’Shea Citation2019). For these reasons, we speculate that reducing cognitive load by limiting the number of simultaneous units may be particularly beneficial for online students, underpinning the more pronounced increase in success observed for the online cohort in this study. As mentioned earlier, it is also possible that improvements to the quality of online delivery following an extended period of COVID-enforced online learning may have also enhanced the success of online students.

Nonetheless, these results are relevant for many HE providers, given that external students typically have among the lowest university completion rates (Cherastidtham and Norton Citation2018). A particularly strong performance enhancement for external students is a promising sign for the effect that a more widespread application of immersive scheduling could have on student success and retention into the future. This is especially salient given the aforementioned reports of rising student preferences for flexible study modes beyond the COVID-19 pandemic (Horstmann Citation2022; Kelly Citation2021).

In contrast to the achievement data, analysis of the student satisfaction data revealed mostly negligible impacts on both unit and teaching satisfaction. The only statistically significant result was an increase in unit satisfaction in the undergraduate business sample. While this sample did not comprise matched-pairs of units, the SCM involved a raft of sweeping curriculum revisions that affected almost all aspects of unit design and delivery. Therefore, it seems highly likely that the immersive model was a contributing factor underpinning the results – although it is not possible to identify which aspects of the model may have contributed most strongly. Previous literature has emphasised that purposeful unit design for shorter delivery formats – including the application of active learning pedagogies, encouraging depth over breadth in learning and adjusted assessment design – can contribute in impactful ways to the student experience, and ultimately to perceptions of unit quality (Scott Citation2003). The undergraduate business students studying in the immersive model clearly found their experience more satisfying than their counterparts in the traditional format.

As and show, unit and teaching satisfaction for other cohorts was already very high in 2019 and there was therefore less potential for improvement in the new delivery model. This constrained potential is consistent with findings from block model implementation at another Australian university, where only small effects on satisfaction were evident (Loton et al. Citation2022). Overall, despite small non-significant decreases for some sub-groups, unit and teaching satisfaction remained high in the immersive model. Unit satisfaction in the new model was 89.14% in the matched-pair units and 86.14% in the undergraduate business units, while teaching satisfaction was 91.09% and 86.63%, respectively. Although there is room for improvement, this does not represent a concerning drop in student satisfaction and indicates that immersive models combining more focused scheduling with active learning approaches can maintain high levels of student satisfaction with both units and teaching.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. At the time of the study, there was a rule change affecting the fail rate in pathways units, whereby from 2021, pathways students who did not submit an assessment were administratively withdrawn at Census Date and were removed from success rate calculations. However, a sensitivity test showed that the removal of AF grades in the data still resulted in a highly statistically significant improvement in success ratesFootnote7 and thus the conclusions drawn remain supported.

Additionally, as mentioned above, the immersive model implemented in this study involved changes to scheduling, pedagogy and curriculum. Given the intertwined nature of those changes, it is not possible to comprehensively disentangle the impact of the change to the calendar from the changes to pedagogy and content delivery. However, consideration of outcomes in the pathways units suggests that these changes in combination are likely to provide better outcomes for students. Similarly, while COVID-19 and changes to special consideration policy may have affected the results in 2021, the extent or nature of the impacts could not be conclusively identified. However, the weaker performance results observed in a control group of units that stayed in the traditional model supports the conclusion that the immersive, active learning model had a significant impact on student success. It is of note that this inclusion also brings a source of variation, in that the units in this group are not the same as those in the immersive scheduling delivery. Despite this variation, the aggregate student achievement outcomes reported here for the control group units serve as a reasonable point of comparison between the delivery models.

Future directions

These limitations highlight the need to collect qualitative and longitudinal data to provide a more fulsome picture of the impact of immersive scheduling models, as well as to better tease out how students’ learning and achievement may be affected by scheduling, changes to curriculum and pedagogy, and the ongoing impacts of COVID-19. There are some examples of qualitative accounts of student experiences in immersive model units at the authors’ institution (Goode, Nieuwoudt, and Roche Citation2022; Goode, Syme, and Nieuwoudt Citation2022; Zhang and Cetinich Citation2022). However, recent qualitative research pertains mostly to a block model in which students undertake one unit at a time over four weeks (Ambler, Solomonides, and Smallridge Citation2021; Jackson et al. Citation2022). A 6-week model allowing students to study two units concurrently presents a different study experience, and further qualitative research will assist in identifying salient factors underpinning enhanced academic success and any declines in student satisfaction. Exploring students’ learning in capstone projects could also provide evidence of graduate outcomes in the SCM.

Further research is also needed to test the assertion that a 6-week immersive scheduling model can, as it has for block models, lead to more pronounced academic achievement gains for students from other cohorts, such as government-defined equity categories (Jackson et al. Citation2022; Winchester, Klein, and Sinnayah Citation2021). Investigating differences in the performance and satisfaction of students with lower and higher prior academic performance could also be a fruitful avenue of inquiry to explore the impact of immersive models on different student cohorts. Finally, the study also focuses on a limited range of disciplines, and extending the scope of the research to assess the model’s performance in fields such as Health, Indigenous Knowledge, Law and Arts will provide evidence for the broader applicability of this model to those fields.

Conclusion

This research evidences that this 6-week immersive model founded in an active and guided pedagogy has, in its pilot year, met the important and ongoing challenge of meeting students’ desires for more flexible modes of study while also supporting more students to succeed in their studies. Improvements in success rates were highly significant for a range of cohorts at pathway, sub-bachelor and Bachelor levels, with particularly strong gains for online students. High levels of student satisfaction were also maintained in the immersive model, with significant improvements for undergraduate business students.

This incipient evidence from this new model of HE is an important contribution in times when institutions worldwide are considering how to sustainably adapt their approaches to teaching and learning beyond the pandemic. The analysis demonstrates that an immersive scheduling model as described here can create the conditions for increasing academic success in HE, in turn supporting students to achieve their educational, longer-term professional and personal goals in a complex post-pandemic era.

Geolocation information

−28.81929988229826, 153.2998814937162.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, along with Dr John Haw and Professor Andrew Rose, who provided valuable feedback on a working version of this manuscript. We also acknowledge the University’s Office of Business, Intelligence and Quality, who assisted us with gathering data for this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In Australia, pathways programmes (also known as enabling programmes) are for domestic applicants who do not meet standard academic entry requirements. They are designed to equip unprepared students for university study and are similar to Access Programs or Bridging Programs in the United Kingdom (UK) and Development Programs in the United States (US) (Syme et al. Citation2022).

2 The Australian government classifies a student as a commencing student ‘if she/he has enrolled in the course for the first time at the higher education institution or an antecedent higher education institution between 1 January of the collection year and 31 December of the collection year’ (DESE Citation2020).

3 Due to COVID-19 border restrictions, international student numbers were not sufficient for a meaningful analysis.

4 A staged release of the SCM meant that not all first-year units were offered in the term model in 2021, and the sample therefore includes one second-year unit.

5 In the teaching periods examined for this study: a Fail (F) was recorded if a student submitted one or more assessment items but did not fulfil the requirements for a Pass grade or higher; an Absent Fail (AF) was recorded if a student did not submit any assessment items and did not withdraw from a unit; and a Withdrawn Fail (WF) was recorded if a student withdrew from a unit after the relevant Census Date.

6 In 2021 a pop-up reminder to complete the Unit Feedback Survey was added to the student learning management system. This may have lifted responses rates relative to 2019.

7 After removing AF grades, a highly statistically significant increase in the enabling cohort success rate in 2021 compared to 2019 was still found (X2 (1, N = 6,194) = 266.92, p < .001).

References

- Akoglu, Haldun. 2018. “User’s Guide to Correlation Coefficients.” Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine 18 (3): 91–93. doi:10.1016/j.tjem.2018.08.001.

- Ambler, Trudy, Ian Solomonides, and Andrew Smallridge. 2021. “Students’ Experiences of a First-Year Block Model Curriculum in Higher Education.” The Curriculum Journal 32 (3): 533–558. doi:10.1002/curj.103.

- Bartolic, Silvia, Uwe Matzat, Joanna Tai, Jamie Lee Burgess, David Boud, Hailey Craig, Audon Archibald, et al. 2022. “Student Vulnerabilities and Confidence in Learning in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Studies in Higher Education. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/03075079.2022.2081679.

- Buck, Ellen, and Katie Tyrrell. 2022. “Block and Blend: A Mixed Method Investigation Into the Impact of a Pilot Block Teaching and Blended Learning Approach upon Student Outcomes and Experience.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 46 (8): 1078–1091. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2022.2050686.

- Burton, Suzan, and Paul Nesbit. 2002. “An Analysis of Student and Faculty Attitudes to Intensive Teaching.” Paper presented at Celebrating Teaching at Macquarie, North Ryde, November 28–29. https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/an-analysis-of-student-and-faculty-attitudes-to-intensive-teachin.

- Cherastidtham, Ittima, and Andrew Norton. 2018. University Attrition: What Helps and What Hinders University Completion? Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/University-attrition-background.pdf.

- Cho, Moon-heum, Seung Won Park, and Sang-eun Lee. 2021. “Student Characteristics and Learning and Teaching Factors Predicting Affective and Motivational Outcomes in Flipped College Classrooms.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (3): 509–522. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1643303.

- Colclasure, Blake C., Sarah E. LaRose, Anna J. Warner, Taylor K. Ruth, J. C. Bunch, Andrew C. Thoron, and T. Grady Roberts. 2018. “Student Perceptions of Accelerated Course Delivery Format for Teacher Preparation Coursework.” Journal of Agricultural Education 59 (3): 58–74. doi:10.5032/jae.2018.03058.

- Davies, W. Martin. 2006. “Intensive Teaching Formats: A Review.” Issues in Educational Research 16 (1): 5–22. http://www.iier.org.au/iier16/davies.html.

- DESE (Department of Educations, Skills and Employment). 2020. 2019 Section 1 Commencing Students. https://www.dese.gov.au/higher-education-statistics/resources/2019-section-1-commencing-students.

- Dixon, Laura, and Valerie O’Gorman. 2020. “‘Block Teaching’ – Exploring Lecturers’ Perceptions of Intensive Modes of Delivery in the Context of Undergraduate Education.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 44 (5): 583–595. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2018.1564024.

- Eames, Michael, Suzanne Luttman, and Susan Parker. 2018. “Accelerated vs. Traditional Accounting Education and CPA Exam Performance.” Journal of Accounting Education 44: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jaccedu.2018.04.004.

- Faught, Brent E., Madelyn Law, and Michelle Zahradnik. 2016. How Much Do Students Remember Over Time? Longitudinal Knowledge Retention in Traditional Versus Accelerated Learning Environments. Toronto: The Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario. https://heqco.ca/pub/how-much-do-students-remember-over-time-longitudinal-knowledge-retention-in-traditional-versus-accelerated-learning-environments/.

- Field, Andy. 2018. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. 5th ed. London: Sage.

- Freeman, Scott, Sarah L. Eddy, Miles McDonough, Michelle K. Smith, Nnadozie Okoroafor, Hannah Jordt, and Mary Pat Wenderoth. 2014. “Active Learning Increases Student Performance in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (23): 8410–8415. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319030111.

- Goode, Elizabeth, Johanna E. Nieuwoudt, and Thomas Roche. 2022. “Does Online Engagement Matter? The Impact of Interactive Learning Modules and Synchronous Class Attendance on Student Achievement in an Immersive Delivery Model.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 38 (4): 76–94. doi:10.14742/ajet.7929.

- Goode, Elizabeth, Thomas Roche, Erica Wilson, and John McKenzie. 2022. “Piloting the Southern Cross Model: Implications of Immersive Scheduling for Student Achievement and Feedback.” Southern Cross University Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Paper No. 5. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4154092.

- Goode, Elizabeth, Suzi Syme, and Johanna E. Nieuwoudt. 2022. “The Impact of Immersive Scheduling on Student Learning and Success in an Australian Pathways Program.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/14703297.2022.2157304.

- Harvey, Marina, Michelle Power, and Michael Wilson. 2017. “A Review of Intensive Mode of Delivery and Science Subjects in Australian Universities.” Journal of Biological Education 51 (3): 315–325. doi:10.1080/00219266.2016.1217912.

- Hattie, John, and Helen Timperley. 2007. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 77 (1): 81–112. doi:10.3102/003465430298487.

- Hellmundt, Suzi, and Dallas Baker. 2017. “Encouraging Engagement in Enabling Programs: The Students’ Perspective.” Student Success 8 (1): 25–33. doi:10.5204/ssj.v8i1.357.

- Horstmann, Nina. 2022. “Students Wish to Have More Online Learning Even after the Pandemic.” Center for Higher Education, January 10. https://www.che.de/en/2022/students-wish-to-have-more-online-learning-even-after-the-pandemic/.

- Jackson, Jen, Kathy Tangalakis, Peter Hurley, and Ian Solomonides. 2022. Equity through Complexity: Inside the “Black Box” of the Block Model. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/publications/black-box-block-model/.

- Joyner, David A., and Charles Isbell. 2021. The Distributed Classroom. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kalyuga, Slava. 2012. “Interactive Distance Education: A Cognitive Load Perspective.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education 24 (3): 182–208. doi:10.1007/s12528-012-9060-4.

- Kellermann, David. 2021. “Academics aren’t content creators, and it’s regressive to make them so.” Times Higher Education, March 8. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/opinion/academics-arent-content-creators-and-its-regressive-make-them-so.

- Kelly, Rhea. 2021. “73 Percent of Students Prefer Some Courses be Fully Online Post-Pandemic.” Campus Technology, May 13. https://campustechnology.com/articles/2021/05/13/73-percent-of-students-prefer-some-courses-be-fully-online-post-pandemic.aspx.

- Lee, Nicolette, and Briony Horsfall. 2010. “Accelerated Learning: A Study of Faculty and Student Experiences.” Innovative Higher Education 35 (3): 191–202. doi:10.1007/s10755-010-9141-0.

- Lodge, Jason M. 2018. “Why Block Subjects Might Not be Best for University Student Learning.” The Conversation, October 11. https://theconversation.com/why-block-subjects-might-not-be-best-for-university-student-learning-102909.

- Loton, Daniel, Cameron Stein, Philip Parker, and Mary Weaven. 2022. “Introducing Block Mode to First-Year University Students: A Natural Experiment on Satisfaction and Performance.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (6): 1097–1120. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1843150.

- Lutes, Lyndell, and Randall Davies. 2018. “Comparison of Workload for University Core Courses Taught in Regular Semester and Time-Compressed Term Formats.” Education Sciences 8 (1): 34–12. doi:10.3390/educsci8010034.

- Mason, Raina, Carolyn Seton, and Graham Cooper. 2016. “Applying Cognitive Load Theory to the Redesign of a Conventional Database Systems Course.” Computer Science Education 26 (1): 68–87. doi:10.1080/08993408.2016.1160597.

- Mayer, Richard E. 2004. “Should There Be a Three-Strikes Rule Against Pure Discovery Learning? The Case for Guided Methods of Instruction.” American Psychologist 59 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.14.

- McHugh, Mary L. 2018. “Cramér’s V Coefficient.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation, edited by Bruce B. Frey, 417–419. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Mercer-Mapstone, Lucy, Tahlia Fatnowna, Pauline Ross, Lisa Bricknell, William Mude, Janelle Wheat, Ryan P. Barone, et al. 2022. Recommendations for Equitable Student Support during Disruptions to the Higher Education Sector: Lessons from COVID-19. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/publications/equitable-student-support-disruptions-higher-education-covid-19/.

- Nerantzi, Chrissy, and Gerasimos Chatzidamianos. 2020. “Moving to Block Teaching During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Management and Applied Research 7 (4): 482–495. doi:10.18646/2056.74.20-034.

- Nieuwoudt, Johanna Elizabeth. 2018. “Exploring Online Interaction and Online Learner Participation in an Online Science Subject Through the Lens of the Interaction Equivalence Theorem.” Student Success 9 (4): 53–62. doi:10.5204/ssj.v9i4.520.

- Richmond, Aaron S., Bridget C. Murphy, Layton S. Curl, and Kristin A. Broussard. 2015. “The Effect of Immersion Scheduling on Academic Performance and Students’ Ratings of Instructors.” Teaching of Psychology 42 (1): 26–33. doi:10.1177/0098628314562675.

- Roche, Thomas, Erica Wilson, and Elizabeth Goode. 2022. “Why the Southern Cross Model? How One University’s Curriculum was Transformed.” Southern Cross University Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Paper No. 3. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4029237.

- Samarawickrema, Gayani, Kaye Cleary, Sally Male, and Trish McCluskey. 2022. Designing Learning for Intensive Modes of Study. Hammondville, Australia: Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia.

- Schneider, Michael, and Franzis Preckel. 2017. “Variables Associated with Achievement in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses.” Psychological Bulletin 143 (6): 565–600. doi:10.1037/bul0000098.

- Scott, Patricia A. 2003. “Attributes of High-Quality Intensive Courses.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 97: 29–38. doi:10.1002/ace.86.

- Skulmowski, Alexander, and Kate Man Xu. 2022. “Understanding Cognitive Load in Digital and Online Learning: A New Perspective on Extraneous Cognitive Load.” Educational Psychology Review 34 (1): 171–96. doi:10.1007/s10648-021-09624-7.

- Smith, Calvin D., and Chi Baik. 2021. “High-Impact Teaching Practices in Higher Education: A Best Evidence Review.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (8): 1696–1713. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1698539.

- Stone, Cathy, and Sarah O’Shea. 2019. “Older, Online and First: Recommendations for Retention and Success.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 35 (1): 57–69. doi:10.14742/ajet.3913.

- Sweller, John. 1988. “Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning.” Cognitive Science 12 (2): 257–285. doi:10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4.

- Syme, Suzi, Thomas Roche, Elizabeth Goode, and Erin Crandon. 2022. “Transforming Lives: The Power of an Australian Enabling Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 41 (7): 2426–2440. doi:10.1080/07294360.2021.1990222

- Thomas, Liz, Sally Kift, and Mahsood Shah. 2021. “Student Retention and Success in Higher Education.” In Student Retention and Success in Higher Education: Institutional Change for the 21st Century, edited by Mahsood Shah, Sally Kift, and Liz Thomas, 1–16. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Turner, Rebecca, Oliver J. Webb, and Debby R.E. Cotton. 2021. “Introducing Immersive Scheduling in a UK University: Potential Implications for Student Attainment.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 45 (10): 1371–1384. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2021.1873252.

- Walsh, Katharine P., Megan Sanders, and Soniya Gadgil. 2019. “Equivalent but Not the Same: Teaching and Learning in Full Semester and Condensed Summer Courses.” College Teaching 67 (2): 138–149. doi:10.1080/87567555.2019.1579702.

- Williams, Tom. 2023. “Block Teaching Advocates Team up After ‘Explosion’ of Interest.” Times Higher Education, January 9. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/block-teaching-advocates-team-after-explosion-interest.

- Willingham, Daniel T. 2017. “A Mental Model of the Learner: Teaching the Basic Science of Educational Psychology to Future Teachers.” Mind, Brain, and Education 11 (4): 166–175. doi:10.1111/mbe.12155.

- Winchester, Maxwell, Rudi Klein, and Puspha Sinnayah. 2021. “Block Teaching and Active Learning Improves Academic Outcomes for Disadvantaged Undergraduate Groups.” Issues in Educational Research 31 (4): 1330–1350. https://www.iier.org.au/iier31/winchester.pdf.

- Wolfe, Julianne K., and David W. Andrews. 2014. “The Changing Roles of Higher Education: Curator, Evaluator, Connector and Analyst.” On the Horizon 22 (3): 210–217. doi:10.1108/OTH-05-2014-0019.

- Zhang, Jacky, and Robyn Cetinich. 2022. “Exploring the Learning Experience of International Students Enrolled in the Southern Cross Model.” Southern Cross University Scholarship of Learning and Teaching Paper No. 4. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4053193.