?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Global mobile marketers are intensifying efforts to promote mobile applications, yet little literature addresses the effectiveness of these strategies on consumer adoption. This study investigates the impact of two mobile marketing strategies—in-app coupons and group-coupons—on mobile app adoption, considering the installed user base moderation. Utilizing data from a Chinese shopping mall, this study shows that both strategies can foster adoption, with opposite moderating effects from existing adopters. Two experiments validate social influence and scarcity perception as underlying mechanisms. These findings highlight the dynamic nature of mobile marketing, urging global mobile marketers to consider this in their strategies.

Introduction

In recent years, the global mobile application market has experienced immense growth with the rapid penetration of mobile devices. From year 2016 to 2022, there were more than 255 billion mobile app downloads worldwide on the Google Play store, the iOS Apple App Store and third-party Android stores (Statista, Citation2023). Companies not only develop their mobile apps for domestic market, but also extend their reach internationally. Consequently, it is imperative for companies to understand strategies for launching their mobile apps on a global scale and increasing consumer adoption in both national and international market.

To enhance consumer adoption, companies have already devoted considerable marketing efforts to strategically promote their apps. In particular, in-app coupons, including regular coupons and group-buying coupons, have become one of the most commonly utilized marketing strategies. An in-app regular coupon is an electronic ticket delivered or solicited via mobile phones that can be exchanged for a financial discount or rebate when consumers make purchases (Mobile Marketing Association, Citation2007). For example, Whole Foods Markets issued in-app coupons to incentivize consumers with discounts upon installing the Whole Foods mobile app (McNew, Citation2016). Similarly, McDonald’s offered a “buy one Big Mac get one free” deal to consumers who downloaded the McDonald’s app and completed registration when the app was introduced (Pope, Citation2015).

Group-buying coupons, as a special form of in-app coupons, are also frequently issued to provide discounted products or services, activated only when a certain number of people pay for the deal (Hu & Winer, Citation2017; Jing & Xie, Citation2011; Song et al., Citation2016). These group-coupons typically have a pre-specified maximum number of coupons (Edelman et al., Citation2016; Hu et al., Citation2019), concurrently indicating savings, remaining purchase time, and number of individuals who have downloaded/redeemed the vouchers (Luo et al., Citation2014). In the global market, as Chinese e-commerce has experienced a remarkable and rapid growth in recent years (Sun & Xu, Citation2019), group-buying coupons have also gained significant popularity. For example, Pinduoduo, a Chinese e-commerce platform specializing in cost-effective group-buying products (or “team purchases”), attracted over 20 million registered users by February 2016, only six months after its launch in September 2015 (Team, C Citation2019). Starting from 2022, Pinduoduo expanded its business model to the global market and launched a new e-commerce platform, Temu, which similarly emphasizes the group-buying experience. Recently, it became the most downloaded app in the US (Toh, Citation2023).

Despite the widespread use of in-app marketing strategies, there is a gap in understanding whether and how these strategies can affect consumer adoption of mobile applications. Numerous studies have probed into the determinants shaping consumer adoption of mobile apps, primarily focused on mobile app features and consumer characteristics (e.g., Al Amin et al., Citation2022; Estrader et al., Citation2023; Paas et al., Citation2021; Stocchi et al., Citation2022; Sun et al., Citation2023). Several studies have paved the way for research on mobile application adoption from a marketing perspective, providing empirical evidence regarding the impacts of in-app advertisements and free versions (Arora et al., Citation2017; Deng et al., Citation2023; Ghose & Han, Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2021). However, to the best of our knowledge, none of the existing studies have examined how in-app marketing strategies affect consumer adoption of mobile applications.

In this research, we specifically focus on two in-app marketing strategies, in-app regular coupons and in-app group-buying coupons, and their impacts on consumer adoption of mobile apps. For ease of discussion, we hereafter refer to in-app regular coupons and in-app group-buying coupons as in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons, respectively. We aim to address two key questions: (1) Whether and how do these two types of in-app marketing strategies affect mobile application adoption? (2) To what extent, if any, do social influences from an installed user base (i.e., the existing adopters of a mobile app) moderate these effects?

We posit that in-app coupons and group-coupons have potential to create value, including financial benefits, for consumers. Moreover, considering that consumers might not be aware of this value until they install the apps, social influence and perception of scarcity from an installed user base (i.e., existing adopters) may play crucial moderating roles, either strengthening or weakening the impacts these in-app marketing strategies. Specifically, we suggest that the installed user base induces both a social influence effect and a scarcity effect, thereby generating opposite moderate effects for the in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons.

We empirically test our hypotheses using the daily adoption data of a mobile app obtained from a Chinese shopping mall. Our analyses, based on the daily individual adoption of 1,908,082 consumers over eight months, revealed consistent results. First, our results indicate that both in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons have positive impacts on consumer adoption of mobile apps, suggesting that consumers are concerned about the benefits created from mobile in-app marketing. Notably, we discover that installed user base yields opposite moderating effects. Specifically, the installed user base exhibits a positive moderating effect on the impact of mobile in-app coupons, but a negative moderating effect on the impact of in-app group-coupons. In other words, with an increase in the number of existing adopters, the impact of these two in-app marketing strategies on mobile application adoption appears to be dynamic rather than static in nature.

We conduct two experiments to further validate the underlying mechanisms. With the increase in the number of existing adopters, the social influence of learning and/or signaling prompts consumers to comprehend or infer the benefits originating from the in-app marketing strategies (Gupta et al., Citation1999; Lam et al., Citation2010; Wang & Xie, Citation2011), resulting in the positive moderating effect from the installed user base. However, in instances where in-app group-coupons are issued and the installed user base is small, consumers’ perception of scarcity motivates them to adopt the application and enjoy the exclusive deal within the app. As the installed user base grows, the perception of scarcity will decline, thereby creating a negative moderating effect of the installed user base.

Our study contributes to the existing literature in three ways. First, this study investigates how mobile marketing strategies, particularly in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons, affect consumer adoption of mobile apps. This markedly differs from the previous literature, which predominantly emphasizes app features and consumer characteristics. Second, we posit that the impacts are dynamic and contingent upon the installed user base. We identify the opposite moderating effects for two in-app marketing strategies and validate social influence and perception of scarcity as the underlying mechanism. These findings indicate that marketers should take into account the dynamic impacts of in-app marketing strategies when making decisions, especially in a global context. Lastly, this study presents empirical results derived from one of the most active social commerce environments, such as China, enriching the global marketing literature.

Literature review and hypothesis development

The rapid proliferation of mobile apps has spurred a burgeoning literature on mobile app adoption, with a particular focus on the factors that influence consumer adoption. A majority of these studies, however, have concentrated on mobile app features (e.g., app rank, intrinsic and social features) (Garg et al., Citation2013; Karanam et al., Citation2023), and consumer characteristics (Al Amin et al., Citation2022; Estrader et al., Citation2023; Paas et al., Citation2021; Sun et al., Citation2023). From the mobile marketing perspective, despite existing studies have explored the impact of mobile app adoption on consumer purchases and firm performance (Boyd et al., Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2015; Liu et al., Citation2019), the effectiveness of mobile marketing strategies on mobile app adoption remains uncertain. While recent studies have initiated to investigate the impact of mobile marketing strategies on consumer adoption of mobile apps, focusing on free versions (Arora et al., Citation2017; Deng et al., Citation2023; Lee et al., Citation2021) and mobile in-app advertisements from third parties (Ghose & Han, Citation2014), the impact of in-app marketing strategies initiated by focal firms remains an underexplored area.

We propose that mobile marketing activities within apps (i.e., in-app coupons and group-coupons) can create value, including financial benefits, for potential adopters. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of consumers embracing the app. Furthermore, as crucial sources for consumers to learn about these potential value, the installed user base may serve as moderators, influencing social influences and perception of scarcity, and moderating the impacts of these in-app marketing strategies.

Impact of in-app coupons and group-coupons

We posit that in-app marketing activities could create financial benefits to potential adopters, enhancing the perceived value of a mobile app and, in turn, increasing the likelihood for consumers to adopt the app. Many firms offer financial value to consumers through the use of coupons or group-coupons. This can be a price discount, a free sample, a certain type of promotion, or a gift following a purchase (M. Andrews et al., Citation2016). To stimulate consumer interest in a mobile app, such financial benefits are often provided after they install and use the app for the first time. In-app coupons and group-coupons, in particular, are often utilized by firms as cost-saving or financial benefit certificates. Compared to traditional printed coupons, in-app coupons are much more convenient for consumers to search, store and retrieve. Hence, owing to these potential financial value provided, a large number of in-app coupon or group-coupons can increase consumer interest in adopting the apps.

Differing from in-app coupons, the design of group-coupons exhibits an additional distinctive characteristic: the pre-specified maximum number of group-coupons at the time of their release. Companies may also continually update the remaining number of group-coupons, conveying messages such as “the deal will be sold out soon” to signify scarcity. As a result, consumers may experience strong pressure to make prompt decisions to avoid the regret of missing a good deal. This unique characteristic may lead to consumers’ perception of scarcity, and an incentive to join the group in fear of missing the deal before the maximum number of group-coupons is reached (Luo et al., Citation2014; Marinesi et al., Citation2018; Wu et al., Citation2015), thereby resulting in a positive impact on consumer adoption.

Taken together, we propose the following hypotheses regarding the impact of mobile in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons:

H1: A large number of in-app coupons issued increase the likelihood for consumers to adopt a mobile app.

H2: A large number of in-app group-coupons issued increase the likelihood for consumers to adopt a mobile app.

Moderating effects of the installed user base

Consumers may not be aware of the value originating from in-app coupons and group-coupons without adopting the app. In this context, the social influences between existing and potential adopters may play a crucial role. Our focus is on investigating the moderating effects of the installed user base, where we posit dual effects: a positive influence through social dynamics and, in group-coupon scenarios, a potential negative influence by mitigating the impact of scarcity signaling.

Drawing from social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, Citation1977; Lam et al., Citation2010), individuals engage in various learning processes, observing others’ behavior to avoid potential costs before making decisions. The social influence between existing and potential adopters enables current app users to share information about the app and the benefits derived from in-app marketing activities on social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and so on. Hence, the larger the installed user base of a mobile app, the greater the chances that potential mobile users can learn from existing adopters, creating a social learning effect that enhances the impact of in-app coupons and group-coupons.

Even without direct interaction with existing adopters, a substantial installed user base signals the benefits of in-app marketing activities, enhancing consumer perception of a new technology (Gupta et al., Citation1999; Wang & Xie, Citation2011). Therefore, a larger number of installed user base also signals the benefits of in-app coupons and group-coupons, thereby augmenting their impacts on consumer adoption. Drawing from these theories, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3: The installed user base has a positive moderating effect, such that the positive impact of in-app coupons on mobile application adoption is more pronounced as the installed user base increases.

H4a: The installed user base has a positive moderating effect, such that the positive impact of in-app group-coupons on mobile application adoption is more pronounced as the installed user base increases.

Furthermore, the distinctive characteristic signifying scarcity in group-coupon scenarios should be considered. Perception of scarcity, stimulated by the unique design of in-app group-coupons, may lead consumers to focus more on the benefits (e.g., financial value) provided by these group-coupons, strengthening their motivations to adopt the focal app and generating a more positive effect of group-coupons.

However, as the installed user base expands to a certain scale, there is potential for this positive impact to diminish and become less significant. With a large number of people adopting the app, consumers may feel that the maximum number of group-coupons will be reached in a very short time. Even if they are aware of a great number of group-coupons being released in the app, they would not have the chance to get the deal. Thus, they may not have a strong motivation to adopt the focal app with such a large number of existing adopters. Consequently, we expect that the impact of in-app group-coupons becomes less influential as the size of the installed user base increases. We propose the following:

H4b: The installed user base has a negative moderating effect, such that the positive impact of in-app group-coupons on mobile application adoption is attenuated as the installed user base increases.

Study 1: Empirical data from a large shopping mall

Data and variables

We collect a proprietary dataset from a prominent shopping mall in China to examine both the proposed main effects of in-app marketing strategies and their interaction effects with the installed user base. This four-level mall covers 2.9 million square feet, featuring over 500 well-known brands, comprising retail outlets and dining establishments. From the launch of its mobile app in late April of 2014 to the end of December 2014, a total of 26,687 individuals had registered user accounts.

The dataset comprises three sets of information: mall visitation data, mobile app registration data, and in-app marketing activity data, spanning the period from January 1 to August 15, 2015. The shopping mall employs special technology to detect the MAC address of consumers’ mobile phones (with Wi-Fi active) when they enter/exit the mall. Visitation data includes consumers’ mobile MAC address (referred to as consumers’ ID hereafter) and the time of their arrival and departure for each visit. Mobile app registration data includes the consumers’ ID and the time at which they installed the mobile app and registered an account. The mall employs diverse promotional activities to raise awareness of its app among consumers, including text messages, emails, and posters within the mall, highlighting the benefits of adopting the focal app or showcasing the number of existing adopters.

The shopping mall periodically sends coupons and group-coupon offers to consumers via the mobile app, typically at midnight. Upon downloading the app and completing registration, consumers gain access to all the coupons and group-coupon offers provided within the app. In addition to coupons, the app also offers information about the mall, such as navigation details. We record the daily count of coupons and group-coupons. In total, we compile a panel dataset of 1,920,081 consumers who visited the mall, with 5.1% having an account on the app.

App adoption

The adoption of the app can be measured in various ways, such as downloading and using the app (Stocchi et al., Citation2022). For example, if an individual installs the app but does not use it, they are classified as a non-adopter (Lim et al., Citation2022). In line with this research, a consumer may visit the mall on multiple occasions. If, on a specific day, this consumer installs the app and registers an account, we classify this as an instance of app adoption. Accordingly, the dependent variable for app adoption is a dummy variable that indicates whether the consumer actually adopted the app.

In-app coupons and in-app group-coupons

We count the number of in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons issued each day to measure the intensity of in-app marketing activities. On average, the shopping mall and its stores issued 3.26 in-app coupons and 11.72 in-app group-coupons per day during our data period.

Installed user base

Following the literature on network effects (Brynjolfsson & Kemerer, Citation1996; Wang & Xie, Citation2011), we measure the installed user base as the cumulative number of existing adopters since the beginning of our data period.

Other variables

We also incorporate consumer- and time-specific variables into our analysis. Specifically, we control for shopping frequency and shopping duration (in seconds) of each consumer to capture their interest in the mall. To account for the potential time variation in consumer adoption, we introduce month dummies, a weekend dummy and a holiday dummy, in our analysis. The descriptive statistics of all variables, expect for the month dummies, are summarized in .

Table 1. Variable measures and descriptive statistics (N = 4,591,511).

Model

To investigate the impact of in-app marketing strategies on consumer adoption, we estimate a binary logit model with consumer-specific random effects. This approach is commonly employed when investigating the effects on binary outcomes (i.e., app adoption). We model the probability of adoption and specify our model as follows:

(1)

(1)

Where Pit measures the probability that individual i adopts the app at time t. The parameter estimates β1 − 3 represent the main effects of in-app coupons, in-app group-coupons, and the installed user base, respectively, while β4 − 5 are the parameter estimates for the interactions. The parameter estimates β6 − 9 and γ represent the effects of control variables. νit captures consumers’ heterogeneity, and εit denotes the error term.

Results

We estimate the model using three different specifications to compare the goodness of fit. The first model includes only the control variables, while the second and third models include in-app coupons, group-coupons and their interaction with the installed user base, respectively. Notably, to improve the interpretability of the parameter estimates, we mean-center continuous variables before constructing the interaction terms (Afshartous & Preston, Citation2011). The estimation results are presented in . Model 3 yields a significantly higher log-likelihood than those in Models 1 and 2, implying that incorporating the impact of in-app marketing strategies and interactions with the installed user base significantly improves the goodness of model fit.

Table 2. Estimation results.

Concerning the main effects of the two in-app marketing strategies, we propose that they have positive impacts on mobile app adoption. As shown in Model 2, we observe that both the coefficients of Coupons and Group-Coupons are significantly positive (β1= .068, p < .01; β2= .046, p < .01). These results indicate the positive impacts of these two in-app marketing strategies on consumer adoption of a mobile app, providing empirical evidence in support of H1 and H2. However, the coefficient of installed user base significant negative (β3= −2.37E-05, p < .01), indicating that a larger number of existing adopters might hinder rather than promote mobile app adoption. One possible explanation is that the value of the app’s network has already peaked, diminishing its appeal for newcomers. Additionally, in the context of market saturation, a substantial user base may indicate that the app is entering an already saturated market, making consumers less likely to adopt yet another app in an already crowded space.

With regard to the moderating effect of the installed user base, our results showed that the installed user base positively moderates the impact of in-app coupons on mobile application adoption (β4= 7.91E-06, p < .01), while the interaction with in-app group-coupons is significantly negative (β5= −2.11E-07, p < .01). The positive moderating effect of the installed user base demonstrates the social learning/signaling effects associated with an increased number of existing adopters, amplifying the potential benefits derived from coupons within a mobile application. Conversely, when marketers issue in-app group-coupons, the observed negative moderating effect provides empirical evidence pertaining to the substitutive relationship between the perception of scarcity induced by the design of group-coupons and the social influence from existing adopters. Thus, our findings empirically support H3 and H4b.

Robustness and validity of results

We conduct several additional analyses to validate our results. First, we utilize the random-effect probit regression model as an alternative to estimate the results. The first column of exhibits consistent patterns.

Table 3. Robustness check for alternative models.

Second, we validate our results by analyzing aggregate adoption data. We use the daily number of consumers who had registered for the mobile app as the dependent variable, estimating the results on a daily basis. We control for covariates similarly, calculating shopping frequency and shopping duration as the average of each variable across all consumers, respectively. We employ the truncated negative binomial model, which is a commonly used model for count variables where all values are positive. As shown in the last column of , our key results still hold when analyzing the aggregate adoption data.

Third, we consider the potential endogeneity issues in our estimation. Firms may determine to issue the in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons, based on the existing number of mobile app adopters and other unobservable variables, a potential endogeneity issue might exist. To address this concern, we re-estimate our model using a control function approach. This method is generally appropriate for addressing endogeneity when the dependent variable is not continuous (e.g., binary, multinomial, discrete and so on) (Andrews & Ebbes, Citation2014). Similar to the classical approach, it requires the instruments in the first stage (Rutz & Watson, Citation2019). Hence, we select store traffic from the previous day and the day before the previous day, as well as the number of coupons and group-coupons issued in the previous day as instrument variables. We also follow Stock and Yogo (Citation2005) to conduct a weak instrument identification test. The results of the validity test indicate that these instruments are valid and do not pose any over-identification issues. Specifically, the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistics (see Appendix ) is significant and much larger than any of the critical values, demonstrating the validity of the instruments. The Sargan (score) statistic (Chi-sq: 3.687; p =.1583) also indicates that there is no issue of over-identification. Then, we re-estimate the model, treating in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons as endogenous variables, and regress with instruments first. Following this, we incorporate the residuals obtained from the first stage to re-estimate the logistic model. As reported in , our key findings still hold when the residuals are controlled, indicating that endogeneity does not substantially impact our estimates.

Table 4. Robustness check for endogeneity issues.

Study 2: Experiments

We find empirical evidence that the installed user base yielded opposite moderating effects on the impacts of in-app coupons and in-app group-coupons. We propose that while in-app coupons could create social influence, in-app group-coupons can generate both social influence and perception of scarcity, potentially resulting in an opposite moderating effect. To validate these underlying mechanisms, we conduct two lab experiments to explain how these in-app coupons and group-coupons impact consumer adoption.

In-app coupon effects

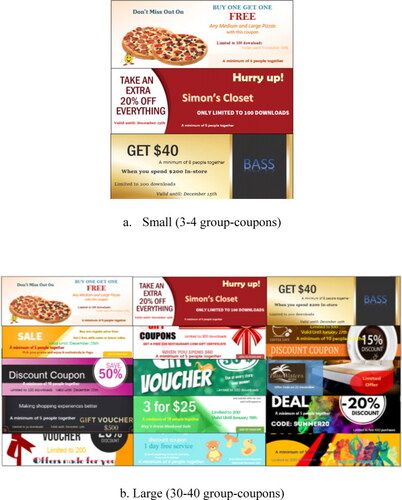

We first examine how in-app coupons interact with the installed user base and affect consumer adoption of a mobile app. In alignment with the subsequent experiment discussing the effects of in-app group-coupons, we test the mediating effect of social influence and consumers’ perception of scarcity arising from in-app coupons. We conduct an experiment using a two-factor (number of coupons: small vs large; number of installed user base: small vs large) between-subjects design. A total of 202 US adults (45.54% male, mean age = 40.85 years old) were recruited from Mturk to participate in the experiment. In-app coupons were manipulated as the number of coupons issued through the mobile app per day (see Appendix ), and the installed user base was manipulated by indicating how many consumers had adopted the app (approximately 100 vs. approximately 100,000).

Participants first viewed examples of mobile app pages with coupons issued and were asked to indicate their intention to adopt this app using a 7-point scale (from 1 = extremely unlikely to 7 = extremely likely). They were then required to rate perception of scarcity (α = .89) and social influence (α = .94) on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = extremely disagree to 7 = extremely agree (see Appendix Experiment constructs and measures). As a manipulation check, they were asked to rate whether they received a large number of coupons in the app and experienced a high number of installed users.

Manipulation check

Independent-sample t-test revealed that participants perceived a greater number of in-app coupons issued in the large condition (M = 5.88, SD = 1.14) compared to those in the small condition (M = 4.30, SD = 1.57; t(200) = 8.26, p < .001). Additionally, participants’ perception of the number of the installed user base was greater in the large condition (M = 6.13, SD = .94) than those in the small condition (M = 3.13, SD = 1.99; t(200) = 13.74, p < .001).

Adoption intention

We conduct a two-way ANOVA on adoption intention. Overall, participants expressed a greater likelihood of adopting the mobile app with a large number of in-app coupons (M = 4.60, SD = 1.98) compared to those with a small number of in-app coupons (M = 4.04, SD = 1.89; F(1,198) = 5.87, p = .016, ηp2 = .029), further supporting H1. Additionally, participants’ adoption intention was higher when the mobile app had a large number of installed user base (M = 4.98, SD = 1.76) compared to those with a small one (M = 3.66, SD = 1.91; F(1,198) = 27.59, p < .01, ηp2 = .122). Notably, the results revealed a marginally significant two-way interaction (F(1,198) = 3.58, p = .06, ηp2 = .018). When the mobile app had a large number of installed user base, adoption intention was greater for the mobile app with a large (vs. small) number of in-app coupons (F(1,198) = 9.43, p < .01, ηp2 = .045). However, when the mobile app had a small number of installed user base, in-app coupons had no significant impact on adoption intention (F(1,198) = .14, p = .71), further supporting H3.

Mediation analysis

We conduct a moderated mediation analysis (PROCESS Model 7, 10,000 bootstraps; Hayes, Citation2013). In this analysis, adoption intention serves as the dependent variable, in-app coupons as the independent variable, installed user base as the moderator, and social influence and perception of scarcity as the mediators. The index of moderated mediation through social influence was significant (B = .50, SE = .20, 95% CI [-0.16, .94]). The conditional indirect effect of in-app coupons through social influence was significant when the mobile app has a large number of installed user base (B = .49, SE = .16, 95% CI [.21, .82]), but not significant in the small user base condition (B = −0.01, SE = .12, 95% CI [-0.25, .23]). Furthermore, the index of moderated mediation through the perception of scarcity was not significant (B = .13, SE = .11, 95% CI [-0.04, .39]).

Discussion

This experiment provides further evidence for the main effect of in-app coupons (H1), its interaction with the installed user base (H3), and the underlying process. The results demonstrate that the indirect effect of in-app coupons through social influence on mobile application adoption persists when consumers encounter a high level of installed user base, but diminishes when facing a small level of installed user base. Meanwhile, it does not indicate any indirect effect of in-app coupons through perception of scarcity on app adoption.

In-app group-coupon effects

To assess the effects of in-app group-coupons, interactions with the installed user base, and the mediating effects of social influence and perception of scarcity, we conduct a similar experiment, utilizing a two-factor (number of group-coupons: small vs large; number of installed user base: small vs large) between-subjects design. A total of 165 US adults (49.09% male, mean age= 39.5 years old) were recruited from Mturk to participate in the experiment. In-app group-coupons were manipulated by varying the number of group-coupons issued through the mobile app per day (Appendix ), and the installed user base was manipulated by specifying the number of consumers who had adopted the app (approximately 100 vs approximately 100,000).

Similar to the in-app coupon experiment, participants initially viewed examples of mobile app pages featuring issued group-coupons and were required to express their intention to adopt this app, their perception of scarcity (α = .82), and social influence (α = .95). To validate the manipulation, participants also rated whether they perceived a large number of group-coupons in the app and encountered a high number of installed users.

Manipulation check

An independent-sample t-test revealed that participants perceived a greater number of group-coupons issued in the condition with a large number of in-app group-coupons (M = 5.09, SD = 1.38) compared to that with small number of in-app group-coupons (M = 4.14, SD = 1.68; t(163) = 3.92, p < .001). Furthermore, participants’ perceptions of the installed user base were greater in the large installed user base condition (M = 5.53, SD = 1.31) than in the small installed user base condition (M = 3.92, SD = 1.77; t(163) = 6.60, p < .001).

Adoption intention

A two-way ANOVA on adoption intention revealed a significant main effect of in-app group-coupons (F(1,161) = 4.49, p = .036, ηp2 = .027). Participants were more likely to adopt the mobile app with a large number of in-app group-coupons (M = 4.28, SD = 1.72) than with a small number (M = 3.70, SD = 1.92), supporting H2. Furthermore, higher adoption intention was observed for the mobile app with a large installed user base (M = 4.39, SD = 1.78) compared to a small one (M = 3.61, SD = 1.83; F(1,161) = 8.61, p < .01, ηp2 = .051). Notably, as expected, there was a significant interaction effect (F(1,161) = 17.75, p < .001, ηp2 = .099). When the mobile app had a small installed user base, adoption intention was significantly higher for the app with a large (vs. small) number of in-app group-coupons (F(1,161) = 20.67, p < .001, ηp2 = .114). However, with a small installed user base, in-app group-coupons did not exert a significant impact on adoption intention (F(1,161) = 2.13, p = .15), further supporting H4b.

Mediation analysis

We employ the PROCESS macro (Model 7; Hayes, Citation2013) with 10,000 bootstrap samples. Adoption intention serves as the dependent variable, in-app coupons as the independent variable, installed user base as the moderator, and social influence and perception of scarcity as the mediators. In examining perception of scarcity as the mediator, the index of moderated mediation was significant (B = −0.33, SE = .20, 95% CI [-0.80, −0.03]). The indirect effect of in-app group-coupons through perception of scarcity was significant when the mobile app had a small number of installed user base (B = .23, SE = .14, 95% CI [.02, .56]), but not significant in the large user base condition (B = −0.10, SE = .11, 95% CI [-0.35, .08]). However, when examining social influence as the mediator, the index of moderated mediation was not significant (B = .02, SE = .15, 95% CI [-0.31, .31]). The social influence from the installed user base did not significantly affect the effectiveness of in-app group-coupons in this context.

Discussion

This experiment provides additional support for the main effect of in-app group-coupons (H2), its interaction with the installed user base (H4b), and the associated underlying process. Within this experiment, we unveil the indirect effect of in-app group-coupons through the perception of scarcity, which is evident when consumers experience a low level of the installed user base but diminishes when consumers encounter a high level. Nevertheless, no indirect effect through social influence is observed. This result, in comparison with in-app coupons, signifies a distinct moderating effect of the installed user base for in-app group-coupons.

Conclusion

Discussion

We set out to investigate the impact of in-app marketing strategies on mobile app adoption, with a specific emphasis on in-app coupons and group-coupons, as well as the moderating effect of the installed user base. Our empirical results indicate that both in-app coupons and group-coupons exert a positive influence on mobile app adoption, and these effects vary contingent upon the installed user base. Specifically, as the number of existing adopters increases, the positive impact of in-app coupons becomes more pronounced, whereas the positive impact of in-app group-coupons diminishes, suggesting a dynamic pattern. We validate social influence and perception of scarcity as the underlying mechanism through experiments.

Our findings contribute to the mobile marketing literature and provide significant implications for global marketers when launching mobile applications. First, despite the growing literature exploring factors influencing mobile app adoption (e.g., Paas et al., Citation2021; Stocchi et al., Citation2022; Sun et al., Citation2023), as well as the impact of mobile app adoption on consumer purchases and firm performance (Boyd et al., Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2015; Liu et al., Citation2019), limited attention has been devoted to how mobile marketing strategies influence consumer adoption of mobile apps. With privacy considerations gaining substantial attention globally and marketers having fewer choices for targeting consumers and promoting products (Cooper et al., Citation2023), in-app mobile marketing strategies have become crucial for marketers to reach their consumers. Our study addresses this gap by examining the effectiveness of in-app coupons and group-coupons in mobile app adoption, thereby extending the existing literature on the determinants of mobile app adoption from a mobile marketing perspective.

Second, our study delves into the influence of group-coupons from a novel perspective. Substantial evidence has been provided on how group-coupons affect consumer behavior (M. Hu et al., Citation2019; Luo et al., Citation2014; M. Song et al., Citation2016; Wu et al., Citation2015), and retailer decisions (Cao et al., Citation2018; Edelman et al., Citation2016; M. Hu et al., Citation2013; Marinesi et al., Citation2018). Our findings suggest that, through the unique design of a pre-specified maximum number, group-coupons can significantly enhance mobile app adoption, contingent upon the installed user base. Our study offers insights into the dynamic effects of group-coupons on mobile app adoption, and contributes to an expanded understanding of the impact of group-coupons.

Third, our study highlights the dynamic impacts of in-app marketing strategies. Our findings suggest that the impact of in-app marketing strategies may differ depending on the installed user base. Drawing upon social learning and signaling theory (Bandura & Walters, Citation1977; Gupta et al., Citation1999; Lam et al., Citation2010; Wang & Xie, Citation2011), we posit and empirically observe the positive moderation of the installed user base on the impact of in-app coupons. However, the installed user base exerts a negative moderating effect on the impact of in-app group-coupons, due to consumers’ perception of scarcity influenced by the number of existing adopters. Consequently, marketers should formulate dynamic mobile marketing strategies in consideration of the mobile app’s lifecycle. This research systematically explores the dynamic implications of in-app marketing activities on mobile app adoption, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding within the mobile marketing literature.

Finally, our study presents empirical evidence on the impact of mobile marketing strategies in the Chinese context, contributing to the global marketing literature. Despite China accounting for more than a half of the world-wide e-commerce sales and the international prominence of Chinese apps in recent years (e.g., Temu, Shein and Tiktok), only a limited number of studies have delved into this global context (Sun & Xu, Citation2019). Based on the empirical results obtained in China, we provide a more complete and comprehensive understanding of the drivers of mobile app adoption in the global marketing literature.

Managerial implications

Our findings offer significant implications for marketers involved in the launch and operation of mobile applications. The trajectory of a mobile app extends beyond its initial launch; indeed, the critical aspect lies in attracting consumers to install and actively engage with the app. Our results indicate that marketers can leverage mobile marketing strategies, such as in-app coupons and group-coupons, to target consumers effectively and enhance adoption. Empirical findings from a Chinese market also empower marketers to tailor in-app marketing strategies to accommodate diverse cultural and economic contexts, thus rendering them more effective in varied global markets.

Importantly, marketers should consider the stage of their mobile app lifecycle (e.g., the early stage with a limited number of adopters versus the late stage with a substantial user base), when developing in-app marketing strategies for different market scenarios. Given the limited space within the app for releasing marketing activities, marketers should carefully allocate this space between the two aforementioned in-app marketing strategies.

Particularly noteworthy is the value created with group-coupons. Although the practice of group-coupons has recently been declining, our study offers evidence concerning the renewed value of group-coupons in driving consumer adoption of mobile apps, especially in the early stage. If marketers enable consumers to voluntarily form a group by leveraging their social networks and by setting a clear expiration time and a limit to the maximum number of group-coupons, as implemented by the new e-commerce platforms Temu and Pinduoduo, they can significantly increase consumer adoption of mobile apps. However, when a certain number of adopters is accumulated, given that in-app group-coupons typically offer more substantial discounts than in-app coupons, marketers may contemplate reducing the frequency of in-app group-coupons and using more in-app coupons to optimize profitability to some extent.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study is subject to some limitations, which provide opportunities for future research. First, while investigating the impact of in-app marketing strategies on consumer adoption of mobile apps based on the number of coupons and group-coupons, it would be more insightful for marketers to access not only to information regarding quantities but also to specifics of in-app marketing activities (e.g., the face value and discount rate of coupons, deal contents, etc.). Additionally, researchers could consider alternative research methodologies, such as field experiments, to disentangle the underlying mechanisms leading to the differential impacts of in-app coupons and group-coupons on mobile application adoption.

Second, exploring the impact of review comments for the focal app and considering their joint impact with in-app marketing activities could be beneficial. During the app download process, consumers often read comments, particularly those from social media influencers (Nistor & Selove, Citation2022). Thus, examining these review characteristics and determining the types of influencers who could be invited to promote the focal app is valuable. Additionally, we investigate the impact of in-app marketing on consumer adoption of the mobile app. However, understanding how these activities influence consumer purchases based on their location and shedding light on geo-targeting strategies is a promising avenue for future research.

Finally, as an initial exploration into the impact of in-app marketing strategies on consumer adoption of mobile apps, we analyzed only the adoption data from one of the largest shopping malls in China, whether these results can be generalized to other contexts remains an avenue for further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afshartous, D., & Preston, R. A. (2011). Key results of interaction models with centering. Journal of Statistics Education, 19(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2011.11889620

- Al Amin, M., Arefin, M. S., Hossain, I., Islam, M. R., Sultana, N., & Hossain, M. N. (2022). Evaluating the determinants of customers’ mobile grocery shopping application (MGSA) adoption during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Global Marketing, 35(3), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2021.1980640

- Andrews, R. L., & Ebbes, P. (2014). Properties of instrumental variables estimation in logit-based demand models: Finite sample results. Journal of Modelling in Management, 9(3), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-07-2014-0062

- Andrews, M., Goehring, J., Hui, S., Pancras, J., & Thornswood, L. (2016). Mobile promotions: A framework and research priorities. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 34, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2016.03.004

- Arora, S., Ter Hofstede, F., & Mahajan, V. (2017). The implications of offering free versions for the performance of paid mobile apps. Journal of Marketing, 81(6), 62–78. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0205

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory. (Vol. 1). Englewood cliffs Prentice Hall.

- Boyd, D. E., Kannan, P. K., & Slotegraaf, R. J. (2019). Branded apps and their impact on firm value: A design perspective. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022243718820588

- Brynjolfsson, E., & Kemerer, C. F. (1996). Network externalities in microcomputer software: An econometric analysis of the spreadsheet market. Management Science, 42(12), 1627–1647. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.42.12.1627

- Cao, Z., Hui, K. L., & Xu, H. (2018). When discounts hurt sales: The case of daily-deal markets. Information Systems Research, 29(3), 567–591. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2017.0772

- Cooper, D. A., Yalcin, T., Nistor, C., Macrini, M., & Pehlivan, E. (2023). Privacy considerations for online advertising: A stakeholder’s perspective to programmatic advertising. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 40(2), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-04-2021-4577

- Deng, Y., Lambrecht, A., & Liu, Y. (2023). Spillover effects and freemium strategy in the mobile app market. Management Science, 69(9), 5018–5041. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.4619

- Edelman, B., Jaffe, S., & Kominers, S. D. (2016). To groupon or not to groupon: The profitability of deep discounts. Marketing Letters, 27(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-014-9289-y

- Estrader, J., Song, J., & Li, X. (2023). Affective contagion effects in cross-cultural mobile marketing: Evaluative conditioning experiments with foreign users. Journal of Global Marketing, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2023.2274072

- Fischhoff, B., Gonzalez, R. M., Small, D. A., & Lerner, J. S. (2003). Judged terror risk and proximity to the World Trade Center. The Risks of Terrorism, 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-6787-2_3

- Garg, R., & Telang, R, The University of Texas at Austin. (2013). Inferring app demand from publicly available data. MIS Quarterly, 37(4), 1253–1264. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.4.12

- Ghose, A., & Han, S. P. (2014). Estimating demand for mobile applications in the new economy. Management Science, 60(6), 1470–1488. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.1945

- Gilly, M. C., Graham, J. L., Wolfinbarger, M. F., & Yale, L. J. (1998). A dyadic study of interpersonal information search. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070398262001

- Gupta, S., Jain, D. C., & Sawhney, M. S. (1999). Modeling the evolution of markets with indirect network externalities: An application to digital television. Marketing Science, 18(3), 396–416. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.18.3.396

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

- Hu, M., Dang, C., & Chintagunta, P. K. (2019). Search and learning at a daily deals website. Marketing Science, 38(4), 609–642. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.2019.1156

- Hu, M., Shi, M., & Wu, J. (2013). Simultaneous vs. sequential group-buying mechanisms. Management Science, 59(12), 2805–2822. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2013.1740

- Hu, M. ()., & R. S., Winer. (2017). The “tipping point” feature of social coupons: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(1), 120–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.05.001

- Jing, X., & Xie, J. (2011). Group buying: A new mechanism for selling through social interactions. Management Science, 57(8), 1354–1372. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1366

- Karanam, S. A., Agarwal, A., & Barua, A. (2023). Design for social sharing: The case of mobile apps. Information Systems Research, 34(2), 721–743. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2022.1151

- Kim, S. J., Wang, R. J. H., & Malthouse, E. C. (2015). The effects of adopting and using a brand’s mobile application on customers’ subsequent purchase behavior. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 31, 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2015.05.004

- Lam, S. K., Kraus, F., & Ahearne, M. (2010). The diffusion of market orientation throughout the organization: A social learning theory perspective. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.5.61

- Lee, S., Zhang, J., & Wedel, M. (2021). Managing the versioning decision over an app’s lifetime. Journal of Marketing, 85(6), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429211000068

- Lim, B., Xie, Y., & Haruvy, E. (2022). The impact of mobile app adoption on physical and online channels. Journal of Retailing, 98(3), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2021.10.001

- Liu, H., Lobschat, L., Verhoef, P. C., & Zhao, H. (2019). App adoption: The effect on purchasing of customers who have used a mobile website previously. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 47, 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2018.12.001

- Luo, X., Andrews, M., Song, Y., & Aspara, J. (2014). Group-buying deal popularity. Journal of Marketing, 78(2), 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.12.0422

- Marinesi, S., Girotra, K., & Netessine, S. (2018). The operational advantages of threshold discounting offers. Management Science, 64(6), 2690–2708. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2740

- McNew, B. S. (2016). Will Whole Foods Market’s new loyalty program make a difference? https://www.fool.com/investing/2016/08/31/will-whole-foods-markets-new-loyalty-program-make.aspx.

- Mobile Marketing Association. (2007). Introduction to mobile coupons. https://www.mmaglobal.com/files/mobilecoupons.pdf.

- Nistor, C., & Selove, M. (2022). Influencers: The power of comments. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4118010

- Paas, L. J., Eijdenberg, E. L., & Masurel, E. (2021). Adoption of services and apps on mobile phones by micro-entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Market Research, 63(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785320938293

- Pope, K. (2015). Use this new app from McDonald’s to get free food and other deals. https://www.thepennyhoarder.com/smart-money/mcdonalds-app/.

- Roux, C., Goldsmith, K., & Bonezzi, A. (2015). On the psychology of scarcity: When reminders of resource scarcity promote selfish (and generous) behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(4), ucv048. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv048

- Rutz, O. J., & Watson, G. F. (2019). Endogeneity and marketing strategy research: An overview. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(3), 479–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00630-4

- Song, M., Park, E., Yoo, B., & Jeon, S. (2016). Is the daily deal social shopping?: An empirical analysis of customer panel data. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 33, 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2015.12.001

- Song, J., & Zahedi, F. (2005). A theoretical approach to web design in e-commerce: A belief reinforcement model. Management Science, 51(8), 1219–1235. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0427

- Statista. (2023). Number of mobile app downloads worldwide from 2016 to 2022(in billions). https://www.statista.com/statistics/271644/worldwide-free-and-paid-mobile-app-store-downloads/

- Stocchi, L., Pourazad, N., Michaelidou, N., Tanusondjaja, A., & Harrigan, P. (2022). Marketing research on mobile apps: Past, present and future. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(2), 195–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00815-w

- Stock, J., & Yogo, M. (2005). Asymptotic distributions of instrumental variables statistics with many instruments. Identification and Inference for Econometric Models: Essays in Honor of Thomas Rothenberg, 6, 109–120.

- Sun, X., Cui, X., & Sun, Y. (2023). Understanding the sequential interdependence of mobile app adoption within and across categories. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 40(3), 659–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2023.06.004

- Sun, Q., & Xu, B. (2019). Mobile social commerce: Current state and future directions. Journal of Global Marketing, 32(5), 306–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2019.1620902

- Team, C. (2019). Pinduoduo’s annual active buyers exceeded 483 mn, ranking second in Q2 2019. https://www.chinainternetwatch.com/29694/pinduoduo-q2-2019/.

- Toh, M. (2023). New online superstore surpasses Amazon and Walmart to become most downloaded app in US. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/02/16/tech/temu-shopping-app-us-popularity-intl-hnk/index.html.

- Wang, Q., & Xie, J. (2011). Will consumers be willing to pay more when your competitors adopt your technology? The impacts of the supporting-firm base in markets with network effects. Journal of Marketing, 75(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.75.5.1

- Wu, J., Shi, M., & Hu, M. (2015). Threshold effects in online group buying. Management Science, 61(9), 2025–2040. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2014.2015

Appendix A

Table A1. Weak instrument identification test.

Table A2. Experiment constructs and measurements.